Rho Small GTPase Family in Androgen-Regulated Prostate Cancer Progression and Metastasis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mechanisms Implicated in PCa Progression

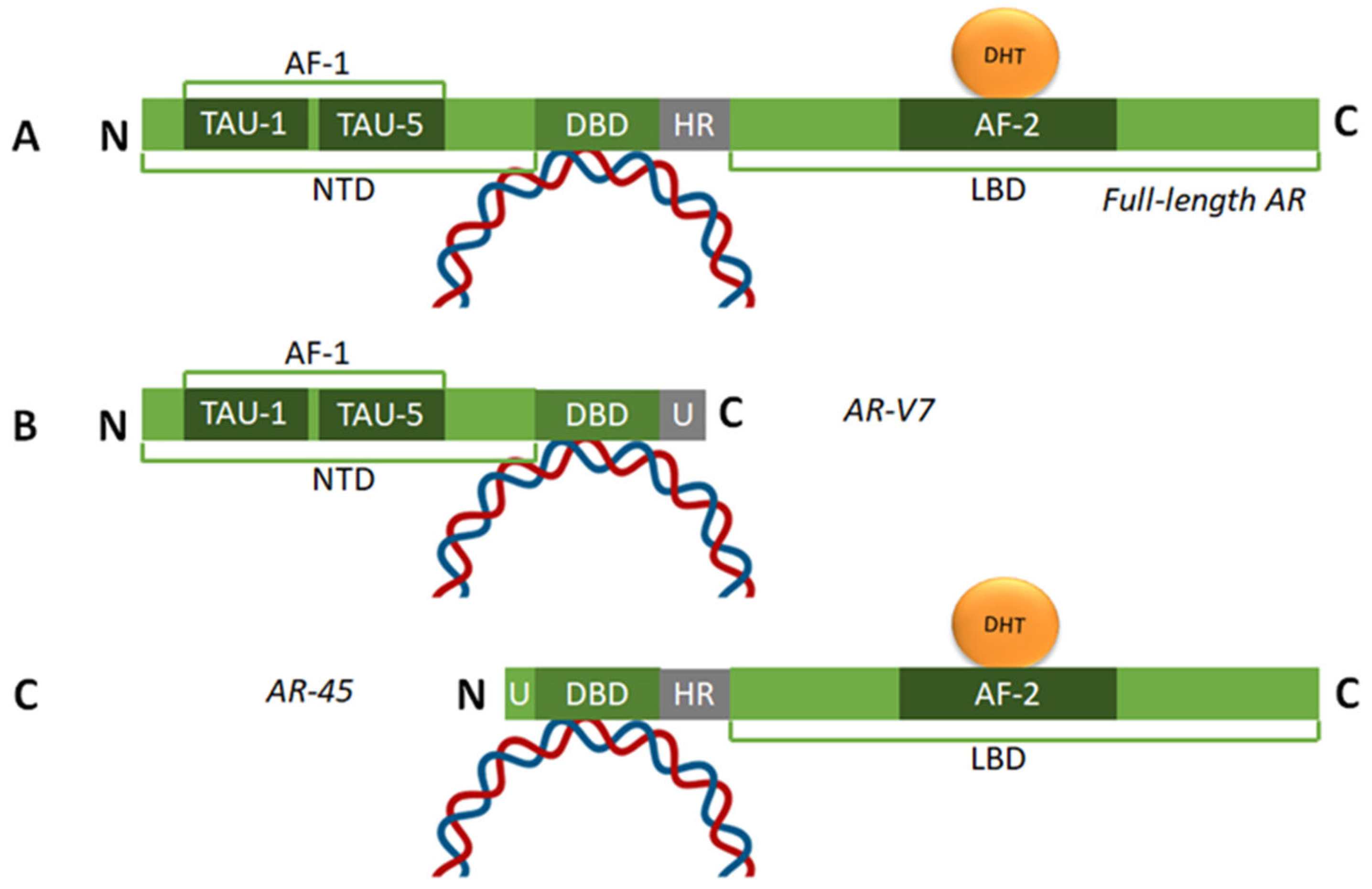

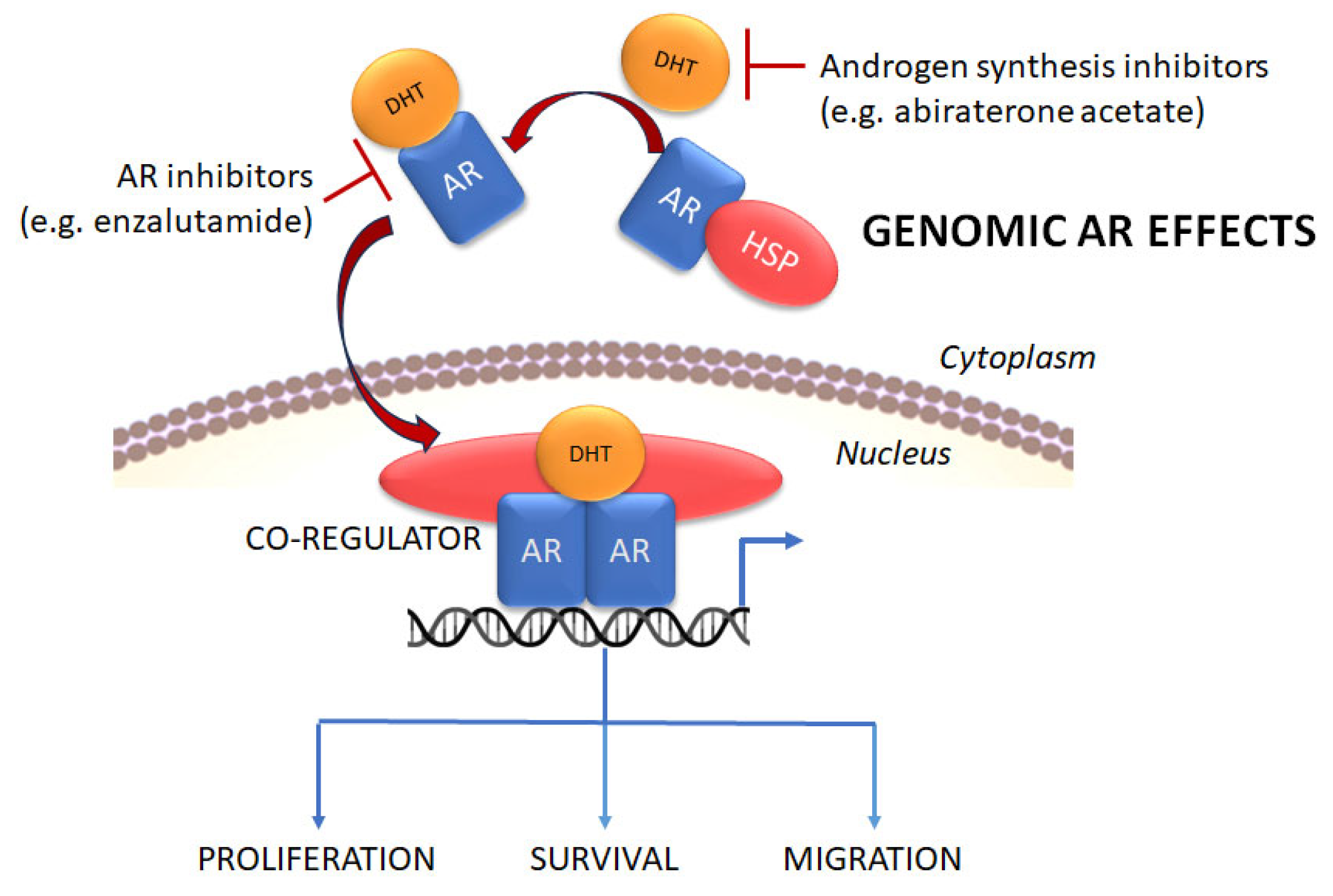

2.1. Structure of the AR and Its Role in PCa Initiation and Development

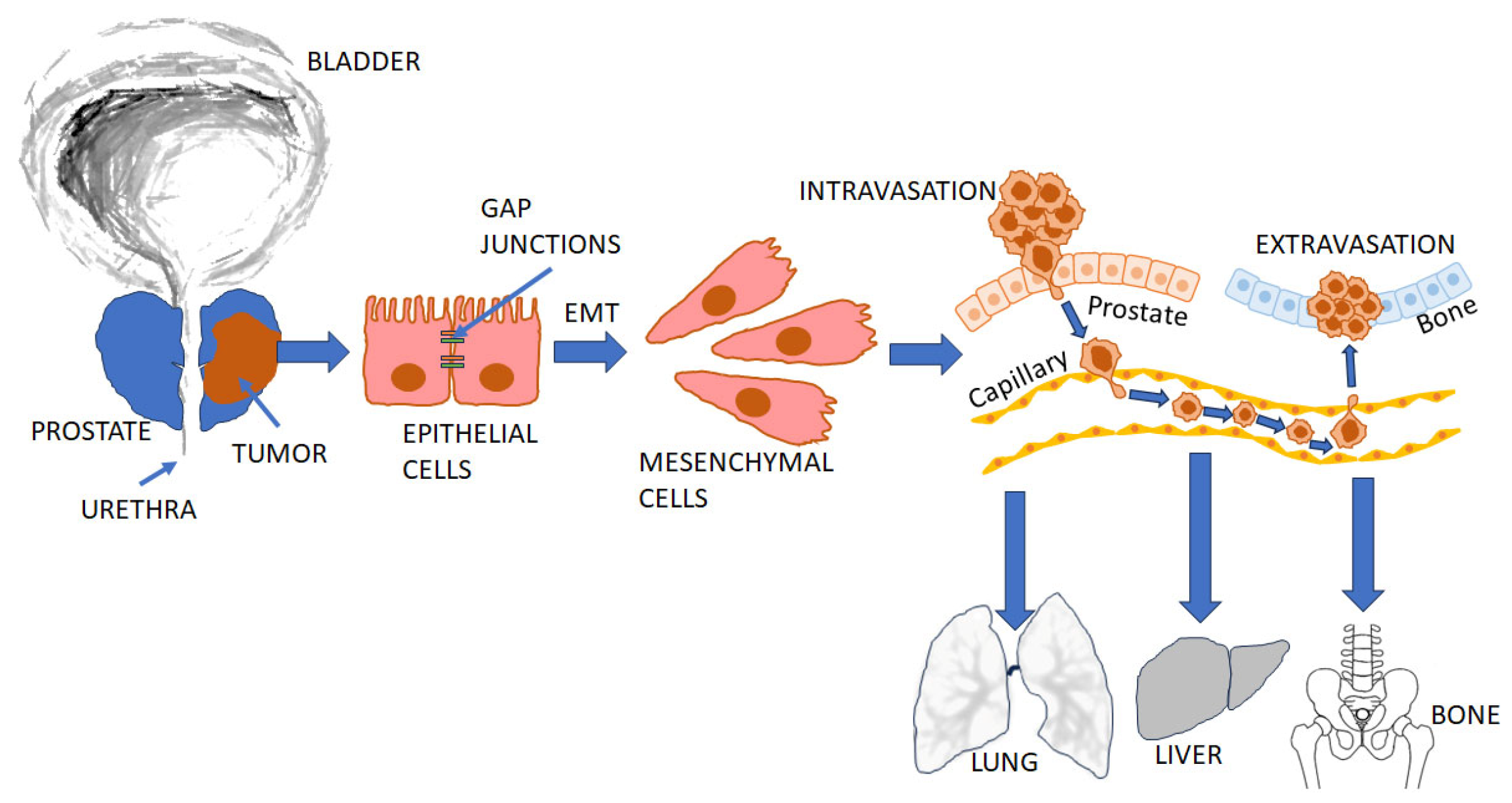

2.2. The Role of the AR in PCa Metastasis

2.3. PCa Treatment and Progression to CRPC

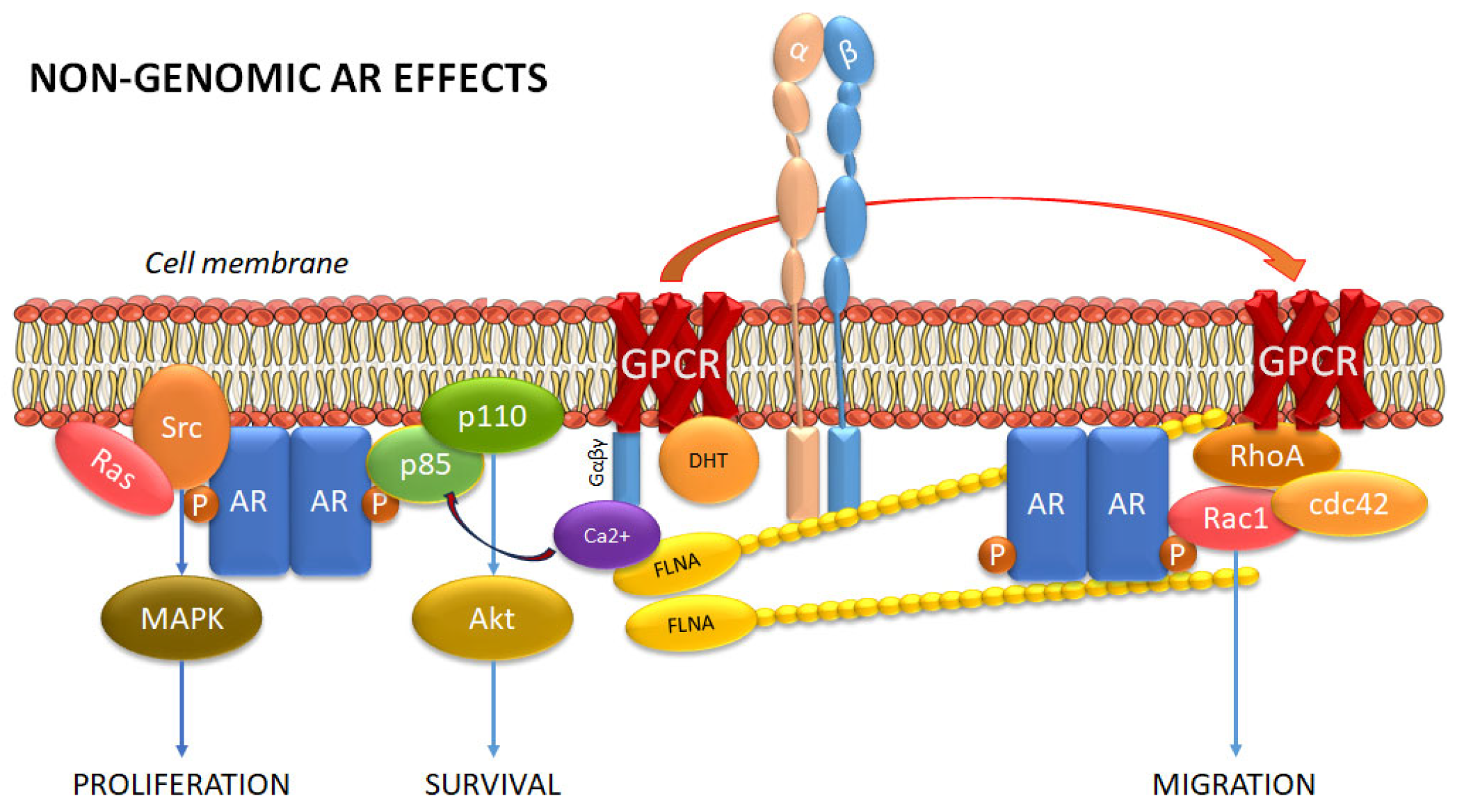

2.4. Membrane Androgen Receptors

3. Rho Family GTPases in PCa Progression

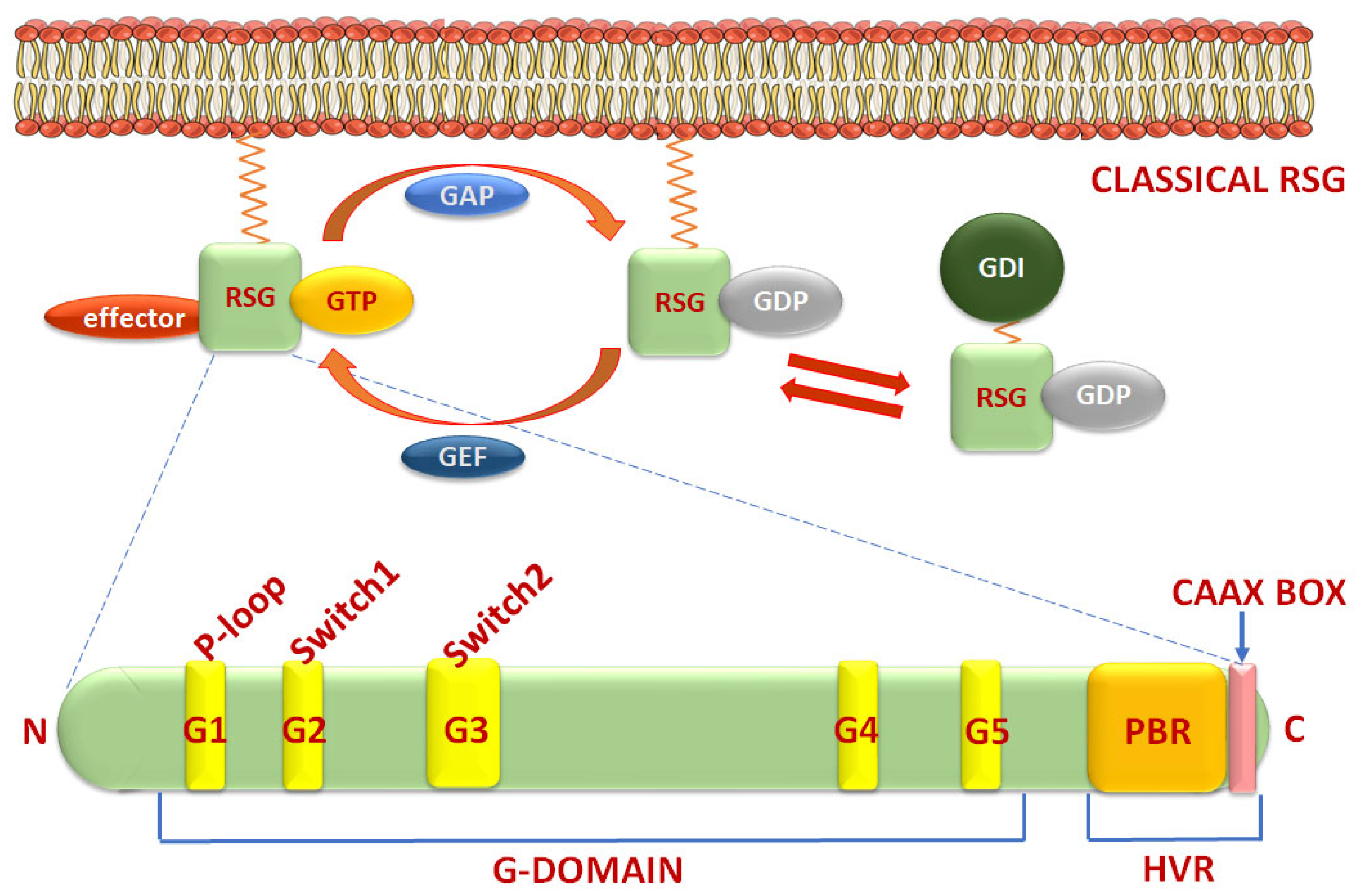

3.1. Structure and Classification of Rho Small GTPases and Regulators

3.2. Regulation of Metastasis by the Rho-GTPase Family in PCa

3.2.1. RhoA/B/C Subfamily

3.2.2. Rac Subfamily

3.2.3. Cdc42 Subfamily

3.2.4. Rif Subfamily

3.2.5. Rnd Subfamily

3.2.6. Wrch Subfamily

3.2.7. RhoH Subfamily

3.2.8. RhoBTB Subfamily

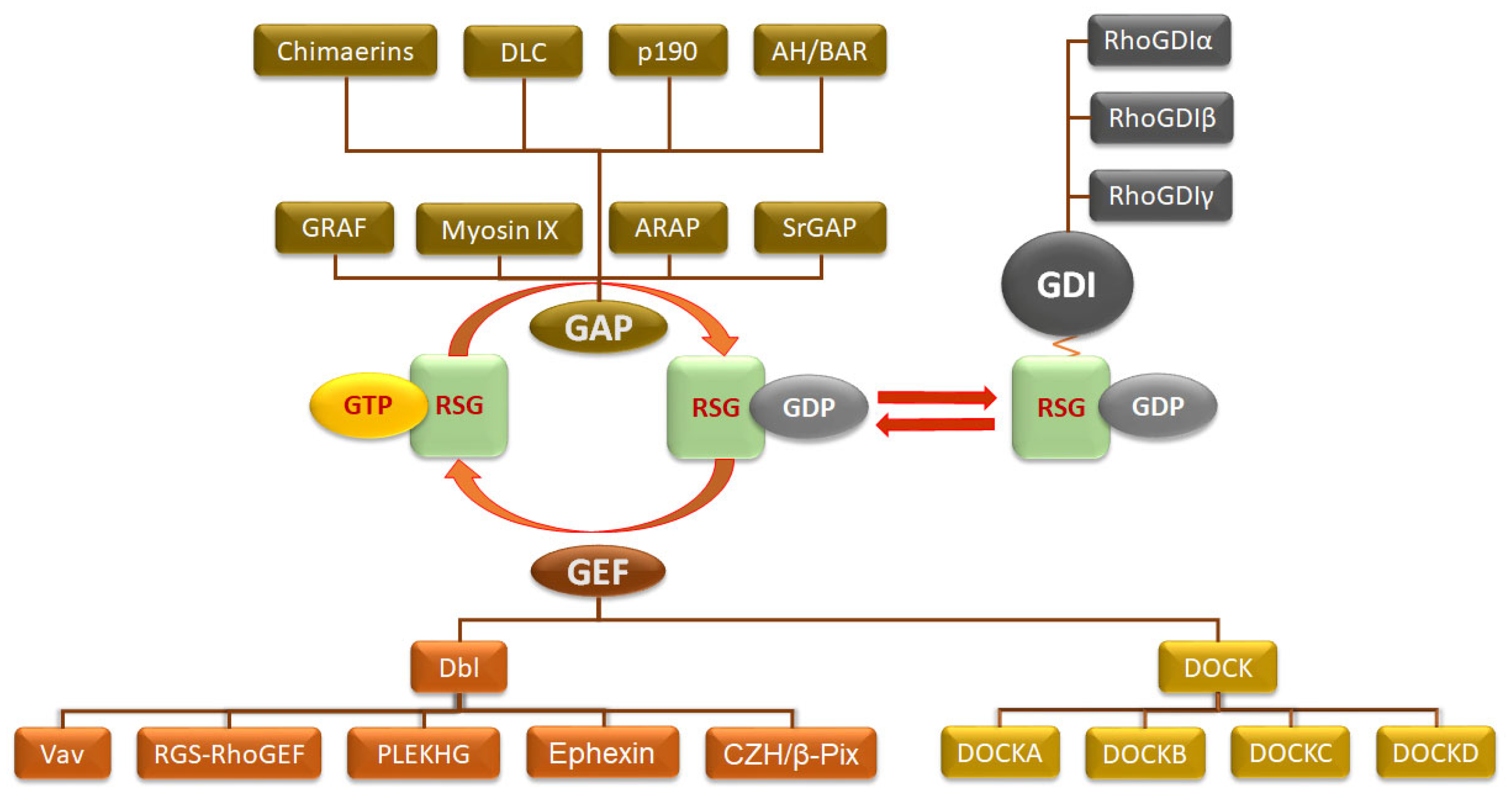

3.3. Regulation of Classical Rho Small GTPases in PCa

3.3.1. Role of GEFs in Rho GTPase Activation

3.3.2. Role of GAPs in Rho GTPase Inactivation

3.3.3. Rho GDP-Dissociation Inhibitor—RhoGDI in PCa

3.4. Regulation of Atypical Rho Small GTPases in PCa

3.5. Regulation of RSG Membrane Binding by Lipidation

3.6. Effects of Genetic Variants on Rho Small GTPase Function in Prostate Cancer

4. Interaction Between Rho Small GTPases and Their Regulators with the Androgen Receptor

4.1. Relationship Between Androgen Receptor and Rho Small GTPases

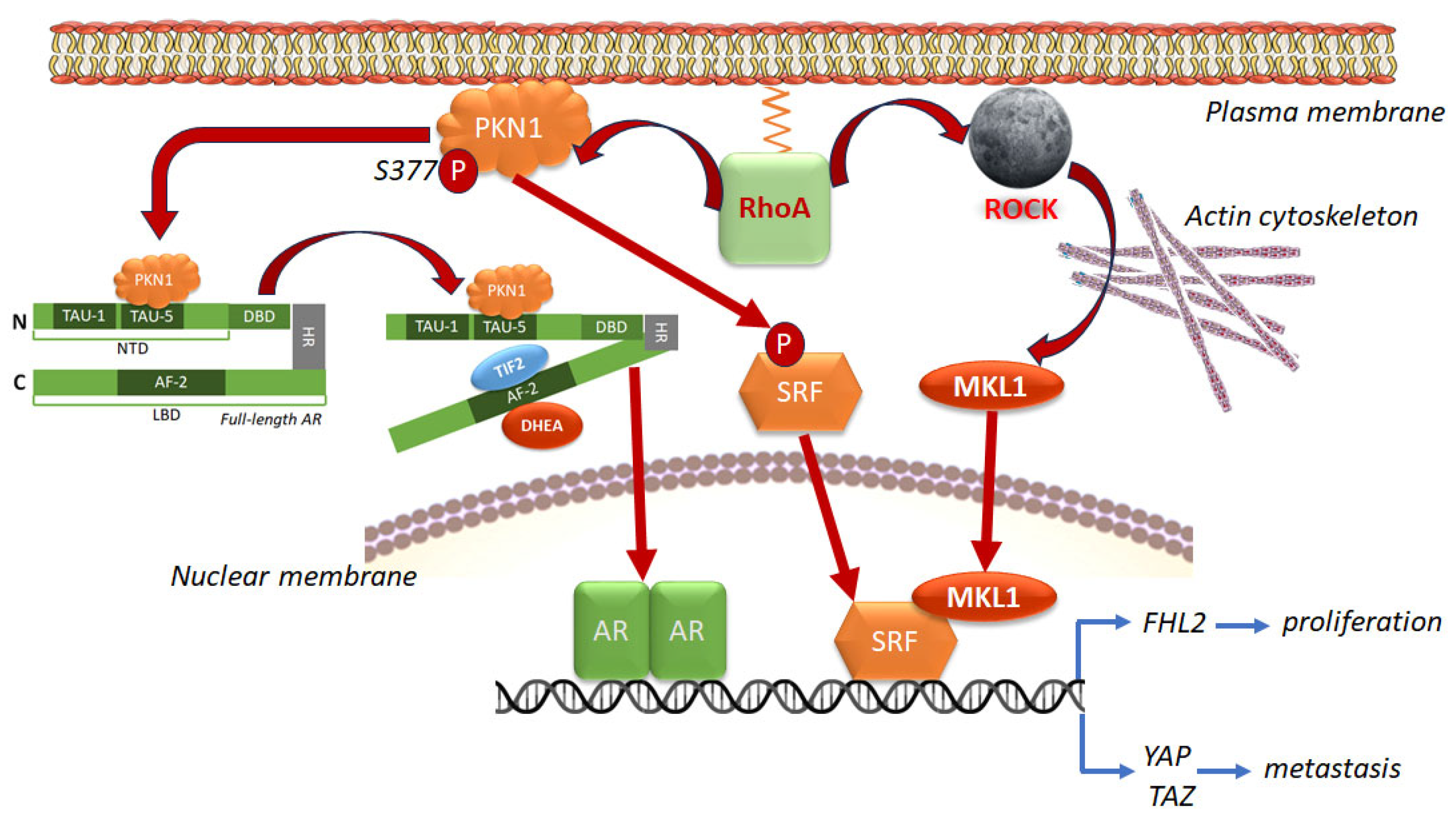

4.1.1. Genomic Interaction Between AR and RhoA via SRF and PKN1/PRK1

4.1.2. RhoA and AR Compensate for Each Other’s Functions

4.1.3. Non-Genomic Interaction Between the AR and RhoA/B

4.1.4. Interaction of the AR with Other Classical Rho Small GTPases

4.2. Linking AR to RSG Dysregulation via Its Regulators

4.2.1. How the AR Controls and Is Controlled by RhoGEFs

4.2.2. How the AR Controls and Is Controlled by RhoGAPs and RhoGDIs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Toivanen, R.; Shen, M.M. Prostate organogenesis: Tissue induction, hormonal regulation and cell type specification. Development 2017, 144, 1382–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, S.W.; Soon-Sutton, T.L.; Skelton, W.P. Prostate Cancer; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Van Blarigan, E.L.; McKinley, M.A.; Washington, S.L., 3rd; Cooperberg, M.R.; Kenfield, S.A.; Cheng, I.; Gomez, S.L. Trends in Prostate Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2456825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, N.S.; Ridley, A.J. Targeting Rho GTPase Signaling Networks in Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takai, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Matozaki, T. Small GTP-binding proteins. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 153–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaron, L.; Franco, O.E.; Hayward, S.W. Review of Prostate Anatomy and Embryology and the Etiology of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 43, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, J.K.; Loeb, S. Environmental exposures and prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2012, 30, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelsman, D.J. Androgen Physiology, Pharmacology, Use and Misuse. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Naamneh Elzenaty, R.; Toit, T.D.; Flück, C.E. Basics of androgen synthesis and action. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 36, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, E.A.; Steele, T.M.; Tsamouri, M.M.; Hejazi, N.; Gao, A.C.; Mudryj, M.; Ghosh, P.M. The Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer: Effect of Structure, Ligands and Spliced Variants on Therapy. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Z.A.; Krauss, D.J. Adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018, 7, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Sun, G.; Shen, P.; Zeng, H. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone receptor agonists and antagonists in prostate cancer: Effects on long-term survival and combined therapy with next-generation hormonal agents. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 1012–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tang, L.; Azabdaftari, G.; Pop, E.; Smith, G.J. Adrenal androgens rescue prostatic dihydrotestosterone production and growth of prostate cancer cells after castration. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2019, 486, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandalo, M.V.; Stocking, J.J.; Pop, E.A.; Wilton, J.H.; Mantione, K.M.; Li, Y.; Attwood, K.M.; Azabdaftari, G.; Wu, Y.; Watt, D.S.; et al. Inhibition of dihydrotestosterone synthesis in prostate cancer by combined frontdoor and backdoor pathway blockade. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 11227–11242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pelekanou, V.; Castanas, E. Androgen Control in Prostate Cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 117, 2224–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sawyers, C.L.; Scher, H.I. Targeting the androgen receptor pathway in prostate cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2008, 8, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoden, E.L.; Averbeck, M.A. Testosterone therapy and prostate carcinoma. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2009, 10, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, K.E.; Garcia-Blanco, M.A.; Armstrong, A.J.; Dehm, S.M. Biologic and clinical significance of androgen receptor variants in castration resistant prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2014, 21, T87–T103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.K.; Dayyani, F.; Gallick, G.E. Steps in prostate cancer progression that lead to bone metastasis. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 2545–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-Y.; Oskarsson, T.; Acharyya, S.; Nguyen, D.X.; Zhang, X.H.-F.; Norton, L.; Massagué, J. Tumor self-seeding by circulating cancer cells. Cell 2009, 139, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, J.; Fares, M.Y.; Khachfe, H.H.; Salhab, H.A.; Fares, Y. Molecular principles of metastasis: A hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppender, N.S.; Morrissey, C.; Lange, P.H.; Vessella, R.L. Dormancy in solid tumors: Implications for prostate cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013, 32, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.J.; Duncan, K.; Yadav, N.; Regan, K.M.; Verone, A.R.; Lohse, C.M.; Pop, E.A.; Attwood, K.; Wilding, G.; Mohler, J.L.; et al. RhoA as a Mediator of Clinically Relevant Androgen Action in Prostate Cancer Cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 716–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, L.S.; Rao, S.; Balkan, W.; Faysal, J.; Maiorino, C.A.; Burnstein, K.L. Ligand-independent activation of androgen receptors by Rho GTPase signaling in prostate cancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Balbas, M.D.; Evans, M.J.; Hosfield, D.J.; Wongvipat, J.; Arora, V.K.; A Watson, P.; Chen, Y.; Greene, G.L.; Shen, Y.; Sawyers, C.L. Overcoming mutation-based resistance to antiandrogens with rational drug design. eLife 2013, 2, e00499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpal, M.; Korn, J.M.; Gao, X.; Rakiec, D.P.; Ruddy, D.A.; Doshi, S.; Yuan, J.; Kovats, S.G.; Kim, S.; Cooke, V.G.; et al. An F876L mutation in androgen receptor confers genetic and phenotypic resistance to MDV3100 (enzalutamide). Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 1030–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraldeschi, R.; Welti, J.; Luo, J.; Attard, G.; de Bono, J.S. Targeting the androgen receptor pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer: Progresses and prospects. Oncogene 2015, 34, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Brown, L.C.; Antonarakis, E.S.; Armstrong, A.J.; Luo, J. Androgen receptor variant-driven prostate cancer II: Advances in laboratory investigations. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020, 23, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, D.M.; Howard, L.E.; Sourbeer, K.N.; Amarasekara, H.S.; Chow, L.C.; Cockrell, D.C.; Hanyok, B.T.; Aronson, W.J.; Kane, C.J.; Terris, M.K.; et al. Predictors of Time to Metastasis in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Urology 2016, 96, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, M.; Hegemann, M.; Rausch, S.; Bedke, J.; Stenzl, A.; Todenhöfer, T. Circulating tumor cells and their role in prostate cancer. Asian J. Androl. 2017, 21, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alexandrova, A.; Lomakina, M. How does plasticity of migration help tumor cells to avoid treatment: Cytoskeletal regulators and potential markers. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 962652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P. Membrane Androgen Receptors Unrelated to Nuclear Steroid Receptors. Endocrinology 2019, 160, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, J.R.; Fletcher, D.K.; McGuigan, M.R. Evidence for a Non-Genomic Action of Testosterone in Skeletal Muscle Which may Improve Athletic Performance: Implications for the Female Athlete. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2012, 11, 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Foradori, C.D.; Weiser, M.J.; Handa, R.J. Non-genomic actions of androgens. Front. Neuroendocr. 2008, 29, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontén, F.; Jirström, K.; Uhlen, M. The Human Protein Atlas—A tool for pathology. J. Pathol. 2008, 216, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyanaraman, H.; Casteel, D.E.; China, S.P.; Zhuang, S.; Boss, G.R.; Pilz, R.B. A plasma membrane-associated form of the androgen receptor enhances nuclear androgen signaling in osteoblasts and prostate cancer cells. Sci. Signal. 2024, 17, eadi7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrens-Fath, I.; Politz, O.; Geserick, C.; Haendler, B. Androgen receptor function is modulated by the tissue-specific AR45 variant. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, N.; Charalampopoulos, I.; Anagnostopoulou, V.; Konstantinidis, G.; Föller, M.; Gravanis, A.; Alevizopoulos, K.; Lang, F.; Stournaras, C. Membrane androgen receptor activation triggers down-regulation of PI-3K/Akt/NF-kappaB activity and induces apoptotic responses via Bad, FasL and caspase-3 in DU145 prostate cancer cells. Mol. Cancer 2008, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fu, X.; Cao, S.; Li, J.; Xing, S.; Li, D.; Dong, Y.; Cardin, D.; Park, H.-W.; Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; et al. Membrane-associated androgen receptor (AR) potentiates its transcriptional activities by activating heat shock protein 27 (HSP27). J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 12719–12729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, R.A.; Grossmann, M. Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2016, 37, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Heemers, H.V.; Tindall, D.J. Androgen Receptor (AR) Coregulators: A Diversity of Functions Converging on and Regulating the AR Transcriptional Complex. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 778–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.S.; Ma, S.; Miao, L.; Li, R.; Yin, Y.; Raj, G.V. Androgen receptor-mediated non-genomic regulation of prostate cancer cell proliferation. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2013, 2, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Koryakina, Y.; Ta, H.Q.; Gioeli, D. Androgen receptor phosphorylation: Biological context and functional consequences. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2014, 21, T131–T145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoy, R.M.; Chen, L.; Siddiqui, S.; Melgoza, F.U.; Durbin-Johnson, B.; Drake, C.; Jathal, M.K.; Bose, S.; Steele, T.M.; Mooso, B.A.; et al. Transcription of Nrdp1 by the androgen receptor is regulated by nuclear filamin A in prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2015, 22, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; I Kreisberg, J.; Bedolla, R.G.; Mikhailova, M.; White, R.W.D.; Ghosh, P.M. A 90 kDa fragment of filamin A promotes Casodex-induced growth inhibition in Casodex-resistant androgen receptor positive C4-2 prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 2007, 26, 6061–6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, P.A.; Arora, V.K.; Sawyers, C.L. Emerging mechanisms of resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundquist, E.A. Small GTPases. WormBook 2006, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murali, A.; Rajalingam, K. Small Rho GTPases in the control of cell shape and mobility. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 1703–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zegers, M.M.; Friedl, P. Rho GTPases in collective cell migration. Small GTPases 2014, 5, e28997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A.M.; Fuentes, G.; Rausell, A.; Valencia, A. The Ras protein superfamily: Evolutionary tree and role of conserved amino acids. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 196, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaddeghzadeh, N.; Ahmadian, M.R. The RHO Family GTPases: Mechanisms of Regulation and Signaling. Cells 2021, 10, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.J.; Mitin, N.; Keller, P.J.; Chenette, E.J.; Madigan, J.P.; Currin, R.O.; Cox, A.D.; Wilson, O.; Kirschmeier, P.; Der, C.J. Rho Family GTPase modification and dependence on CAAX motif-signaled posttranslational modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 25150–25163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.L.; Abo, A.; Lambeth, J.D. Rac “insert region” is a novel effector region that is implicated in the activation of NADPH oxidase, but not PAK65. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 19794–19801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Reinhard, N.R.; Hordijk, P.L. Toward understanding RhoGTPase specificity: Structure, function and local activation. Small GTPases 2014, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthold, J.; Schenkova, K.; Rivero, F. Rho GTPases of the RhoBTB subfamily and tumorigenesis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008, 29, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma-Fukai, S.; Shimizu, T. Structural Insights into the Regulation Mechanism of Small GTPases by GEFs. Molecules 2019, 24, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, E.; Jaiswal, M.; Derewenda, U.; Reis, K.; Nouri, K.; Koessmeier, K.T.; Aspenström, P.; Somlyo, A.V.; Dvorsky, R.; Ahmadian, M.R. Deciphering the Molecular and Functional Basis of RHOGAP Family Proteins: A systematic approach toward selective inactivation of rho family proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 20353–20371. [Google Scholar]

- DerMardirossian, C.; Bokoch, G.M. GDIs: Central regulatory molecules in Rho GTPase activation. Trends Cell Biol. 2005, 15, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, A.J. RhoA, RhoB and RhoC have different roles in cancer cell migration. J. Microsc. 2013, 251, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A.P.; Ridley, A.J. Why three Rho proteins? RhoA, RhoB, RhoC, and cell motility. Exp. Cell Res. 2004, 301, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.M.; Colomba, A.; Reymond, N.; Thomas, M.; Ridley, A.J. RhoB regulates cell migration through altered focal adhesion dynamics. Open Biol. 2012, 2, 120076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerongen, G.P.v.N.; Vermeer, M.A.; van Hinsbergh, V.W.M. Role of RhoA and Rho Kinase in Lysophosphatidic Acid–Induced Endothelial Barrier Dysfunction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000, 20, e127–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymond, N.; Im, J.H.; Garg, R.; Cox, S.; Soyer, M.; Riou, P.; Colomba, A.; Muschel, R.J.; Ridley, A.J. RhoC and ROCKs regulate cancer cell interactions with endothelial cells. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steurer, S.; Hager, B.; Büscheck, F.; Höflmayer, D.; Tsourlakis, M.C.; Minner, S.; Clauditz, T.S.; Hube-Magg, C.; Luebke, A.M.; Simon, R.; et al. Up regulation of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing kinase1 (ROCK1) is associated with genetic instability and poor prognosis in prostate cancer. Aging 2019, 11, 7859–7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, N.; Charalampopoulos, I.; Alevizopoulos, K.; Gravanis, A.; Stournaras, C. Rho/ROCK/actin signaling regulates membrane androgen receptor induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 3162–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julian, L.; Olson, M.F. Rho-associated coiled-coil containing kinases (ROCK): Structure, regulation, and functions. Small GTPases 2014, 5, e29846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin-Zhorov, A.; Flynn, R.; Waksal, S.D.; Blazar, B.R. Isoform-specific targeting of ROCK proteins in immune cells. Small GTPases 2016, 7, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, A.V.; Bernard, O. Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK) signaling and disease. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 48, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakic, A.; DiVito, K.; Fang, S.; Suprynowicz, F.; Gaur, A.; Li, X.; Palechor-Ceron, N.; Simic, V.; Choudhury, S.; Yu, S.; et al. ROCK inhibitor reduces Myc-induced apoptosis and mediates immortalization of human keratinocytes. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66740–66753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, G.C. Actin’ up: RhoB in cancer and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Sun, J.; Cheng, J.; Djeu, J.Y.; Wei, S.; Sebti, S. Akt mediates Ras downregulation of RhoB, a suppressor of transformation, invasion, and metastasis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 5565–5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, T.; Su, H.; Yao, L.; Qu, Z.; Liu, H.; Shao, W.; Zhang, X. RhoB regulates prostate cancer cell proliferation and docetaxel sensitivity via the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, K.-J.; Kim, B.K.; Han, G.; Lee, K.; Jung, Y.-J.; Kim, H.-M.; Bin Song, K.; Chung, K.-S.; Won, M. NSC126188 induces apoptosis of prostate cancer PC-3 cells through inhibition of Akt membrane translocation, FoxO3a activation, and RhoB transcription. Apoptosis 2014, 19, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.M.; Thomas, M.; Reymond, N.; Ridley, A.J. The Rho GTPase RhoB regulates cadherin expression and epithelial cell-cell interaction. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-C.; Boucher, D.L.; Martinez, A.; Tepper, C.G.; Kung, H.-J. Modeling truncated AR expression in a natural androgen responsive environment and identification of RHOB as a direct transcriptional target. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Iiizumi, M.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Pai, S.K.; Watabe, M.; Hirota, S.; Hosobe, S.; Tsukada, T.; Miura, K.; Saito, K.; Furuta, E.; et al. RhoC promotes metastasis via activation of the Pyk2 pathway in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 7613–7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Dashner, E.J.; van Golen, C.M.; van Golen, K.L. RhoC GTPase is required for PC-3 prostate cancer cell invasion but not motility. Oncogene 2006, 25, 2285–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansson, A.; Ceberg, C.; Bjartell, A.; Ceder, J.; Timmermand, O.V. Investigating Ras homolog gene family member C (RhoC) and Ki67 expression following external beam radiation therapy show increased RhoC expression in relapsing prostate cancer xenografts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 728, 150324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuhmacher, J.; Heidu, S.; Balchen, T.; Richardson, J.R.; Schmeltz, C.; Sonne, J.; Schweiker, J.; Rammensee, H.-G.; Straten, P.T.; Røder, M.A.; et al. Vaccination against RhoC induces long-lasting immune responses in patients with prostate cancer: Results from a phase I/II clinical trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennerberg, K.; Der, C.J. Rho-family GTPases: It’s not only Rac and Rho (and I like it). J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Xu, E.; Luo, Q.; Song, G. Rac1: A Regulator of Cell Migration and a Potential Target for Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2023, 28, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M.; Sequeira, L.; Jenkins-Kabaila, M.; Dubyk, C.W.; Pathak, S.; van Golen, K.L. Individual rac GTPases mediate aspects of prostate cancer cell and bone marrow endothelial cell interactions. J. Signal Transduct. 2011, 2011, 541851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Shacter, E. Rac1 inhibits apoptosis in human lymphoma cells by stimulating Bad phosphorylation on Ser-75. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 6205–6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurokawa, K.; Itoh, R.E.; Yoshizaki, H.; Nakamura, Y.O.T.; Matsuda, M. Coactivation of Rac1 and Cdc42 at lamellipodia and membrane ruffles induced by epidermal growth factor. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawada, K.; Upadhyay, G.; Ferandon, S.; Janarthanan, S.; Hall, M.; Vilardaga, J.-P.; Yajnik, V. Cell migration is regulated by platelet-derived growth factor receptor endocytosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 4508–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzima, E.; Del Pozo, M.A.; Kiosses, W.B.; Mohamed, S.A.; Li, S.; Chien, S.; Schwartz, M.A. Activation of Rac1 by shear stress in endothelial cells mediates both cytoskeletal reorganization and effects on gene expression. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 6791–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.K.; Kholodenko, B.N.; von Kriegsheim, A. Rac1 and RhoA: Networks, loops and bistability. Small GTPases 2018, 9, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yin, L.; Qiao, G.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Bai, Y.; Feng, F. Inhibition of Rac1 reverses enzalutamide resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 2997–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnst, J.L.; Hein, A.L.; Taylor, M.A.; Palermo, N.Y.; Contreras, J.I.; Sonawane, Y.A.; Wahl, A.O.; Ouellette, M.M.; Natarajan, A.; Yan, Y. Discovery and characterization of small molecule Rac1 inhibitors. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 34586–34600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zins, K.; Lucas, T.; Reichl, P.; Abraham, D.; Aharinejad, S. A Rac1/Cdc42 GTPase-specific small molecule inhibitor suppresses growth of primary human prostate cancer xenografts and prolongs survival in mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J.C.; Soltys, J.; Okano, K.; Dinauer, M.C.; Doerschuk, C.M. The role of Rac2 in regulating neutrophil production in the bone marrow and circulating neutrophil counts. Am. J. Pathol. 2008, 173, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latonen, L.; Scaravilli, M.; Gillen, A.; Hartikainen, S.; Zhang, F.-P.; Ruusuvuori, P.; Kujala, P.; Poutanen, M.; Visakorpi, T. In Vivo Expression of miR-32 Induces Proliferation in Prostate Epithelium. Am. J. Pathol. 2017, 187, 2546–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, W.; Meng, S.; Liu, B. Nonconserved miR-608 suppresses prostate cancer progression through RAC2/PAK4/LIMK1 and BCL2L1/caspase-3 pathways by targeting the 3′-UTRs of RAC2/BCL2L1 and the coding region of PAK4. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 5716–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-M.; Pan, Y.-T.; Wang, T.-C.V. Cdc42/Rac1 participates in the control of telomerase activity in human nasopharyngeal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2005, 218, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, F.; Wang, G.; Yang, T.; Wei, D.; Guo, L.; Xiao, H. Induction of entosis in prostate cancer cells by nintedanib and its therapeutic implications. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 3151–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Niu, M.; Chen, D.; Chen, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, X.; Ying, H.; Bergholz, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Z.-X. Inhibition of Cdc42 is essential for Mig-6 suppression of cell migration induced by EGF. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 49180–49193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, B.J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Huo, S.; Chen, Y.-H.; Lu, Q. Inhibition of Cdc42-intersectin interaction by small molecule ZCL367 impedes cancer cell cycle progression, proliferation, migration, and tumor growth. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Iguchi, K.; Usui, S.; Hirano, K. Overexpression of thymosin beta4 increases pseudopodia formation in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 32, 1101–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Sowden, M.P.; Gerber, S.A.; Thomas, T.; Christie, C.K.; Mohan, A.; Yin, G.; Lord, E.M.; Berk, B.C.; Pang, J. G-protein-coupled receptor-2-interacting protein-1 is required for endothelial cell directional migration and tumor angiogenesis via cortactin-dependent lamellipodia formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymond, N.; Im, J.H.; Garg, R.; Vega, F.M.; D’aGua, B.B.; Riou, P.; Cox, S.; Valderrama, F.; Muschel, R.J.; Ridley, A.J. Cdc42 promotes transendothelial migration of cancer cells through β1 integrin. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 199, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipes, N.S.; Feng, Y.; Guo, F.; Lee, H.-O.; Chou, F.-S.; Cheng, J.; Mulloy, J.; Zheng, Y. Cdc42 Regulates Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Three Dimensions. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 36469–36477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, H.; Wang, J.; Lv, J.; Zhang, K.; Keller, E.T.; Yao, Z.; Wang, Q. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 promotes prostate cancer progression through activating the Cdc42-PAK1 axis. J. Pathol. 2017, 243, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Xiong, J. Serum CDC42 level change during abiraterone plus prednisone treatment and its association with prognosis in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.-Y.; Chen, S.-Y.; Wu, C.-H.; Lu, C.-C.; Yen, G.-C. Glycyrrhizin Attenuates the Process of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition by Modulating HMGB1 Initiated Novel Signaling Pathway in Prostate Cancer Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 3323–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesland, A.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, L.; Zhou, H.; Lu, Q. Small molecule targeting Cdc42-intersectin interaction disrupts Golgi organization and suppresses cell motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 1261–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Huang, R.; Liu, Y.; Tamalunas, A.; Stief, C.G.; Hennenberg, M. Silencing of CDC42 inhibits contraction and growth-related functions in prostate stromal cells, which is mimicked by ML141. Life Sci. 2023, 329, 121928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, M.; Reis, K.; Heldin, J.; Kreuger, J.; Aspenström, P. The atypical Rho GTPase RhoD is a regulator of actin cytoskeleton dynamics and directed cell migration. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 352, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Polavaram, N.S.; Islam, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bodas, S.; Mayr, T.; Roy, S.; Albala, S.A.Y.; Toma, M.I.; Darehshouri, A.; et al. Neuropilin-2 regulates androgen-receptor transcriptional activity in advanced prostate cancer. Oncogene 2022, 41, 3747–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wong, O.G.-W.; Masters, J.R.; Williamson, M. Effect of cancer-associated mutations in the PlexinB1 gene. Mol. Cancer 2012, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnauld, K.; Nguyen, Q.-D.; Vakaet, L.; Bruyneel, E.; Launay, J.-M.; Endo, T.; Mareel, M.; Gespach, C.; Emami, S. G-protein alpha(olf) subunit promotes cellular invasion, survival, and neuroendocrine differentiation in digestive and urogenital epithelial cells. Oncogene 2002, 21, 4020–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tong, Y.; Hota, P.K.; Hamaneh, M.B.; Buck, M. Insights into oncogenic mutations of plexin-B1 based on the solution structure of the Rho GTPase binding domain. Structure 2008, 16, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorning, B.Y.; Trent, N.; Griffiths, D.F.; Worzfeld, T.; Offermanns, S.; Smalley, M.J.; Williamson, M. Plexin-B1 Mutation Drives Metastasis in Prostate Cancer Mouse Models. Cancer Res. Commun. 2023, 3, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiminty, N.; Dutt, S.; Tepper, C.; Gao, A.C. Microarray analysis reveals potential target genes of NF-κB2/p52 in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2010, 70, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektic, J.; Pfeil, K.; Berger, A.P.; Ramoner, R.; Pelzer, A.; Schäfer, G.; Kofler, K.; Bartsch, G.; Klocker, H. Small G-protein RhoE is underexpressed in prostate cancer and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Prostate 2005, 64, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trojan, L.; Schaaf, A.; Steidler, A.; Haak, M.; Thalmann, G.; Knoll, T.; Gretz, N.; Alken, P.; Michel, M.S. Identification of metastasis-associated genes in prostate cancer by genetic profiling of human prostate cancer cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2005, 25, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paysan, L.; Piquet, L.; Saltel, F.; Moreau, V. Rnd3 in Cancer: A Review of the Evidence for Tumor Promoter or Suppressor. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016, 14, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, W.; Andrade, K.C.; Lin, X.; Yang, X.; Yue, X.; Chang, J. Pathophysiological Functions of Rnd3/RhoE. Compr. Physiol. 2015, 6, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinezhad, S.; Väänänen, R.-M.; Mattsson, J.; Li, Y.; Tallgrén, T.; Ochoa, N.T.; Bjartell, A.; Åkerfelt, M.; Taimen, P.; Boström, P.J.; et al. Validation of Novel Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer Progression by the Combination of Bioinformatics, Clinical and Functional Studies. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155901. [Google Scholar]

- Corradi, J.P.; Cumarasamy, C.W.; Staff, I.; Tortora, J.; Salner, A.; McLaughlin, T.; Wagner, J. Identification of a five gene signature to predict time to biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Prostate 2021, 81, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinezhad, S.; Väänänen, R.-M.; Tallgrén, T.; Perez, I.M.; Jambor, I.; Aronen, H.; Kähkönen, E.; Ettala, O.; Syvänen, K.; Nees, M.; et al. Stratification of aggressive prostate cancer from indolent disease-Prospective controlled trial utilizing expression of 11 genes in apparently benign tissue. Urol. Oncol. 2016, 34, 255.e15–255.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, I.M.; Jambor, I.; Pahikkala, T.; Airola, A.; Merisaari, H.; Saunavaara, J.; Alinezhad, S.; Väänänen, R.; Tallgrén, T.; Verho, J.; et al. Prostate Cancer Risk Stratification in Men with a Clinical Suspicion of Prostate Cancer Using a Unique Biparametric MRI and Expression of 11 Genes in Apparently Benign Tissue: Evaluation Using Machine-Learning Techniques. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 51, 1540–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Piano, M.; Manuelli, V.; Zadra, G.; Otte, J.; Edqvist, P.-H.D.; Pontén, F.; Nowinski, S.; Niaouris, A.; Grigoriadis, A.; Loda, M.; et al. Lipogenic signalling modulates prostate cancer cell adhesion and migration via modification of Rho GTPases. Oncogene 2020, 39, 3666–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Piano, M.; Manuelli, V.; Zadra, G.; Loda, M.; Muir, G.; Chandra, A.; Morris, J.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Wells, C.M. Exploring a role for fatty acid synthase in prostate cancer cell migration. Small GTPases 2021, 12, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, N.S.; Hodge, R.G.; Infante, E.; Alibhai, D.; Zhou, F.; Ridley, A.J. RhoU forms homo-oligomers to regulate cellular responses. J. Cell Sci. 2024, 137, jcs261645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Q.; Peng, B. Prognostic significance of the rho GTPase RHOV and its role in tumor immune cell infiltration: A comprehensive pan-cancer analysis. FEBS Open Bio 2023, 13, 2124–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.-B.; Zhou, J.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.-H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Ma, L.-M.; Chen, Q.; Da, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Normal prostate-derived stromal cells stimulate prostate cancer development. Cancer Sci. 2011, 102, 1630–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajadura-Ortega, V.; Garg, R.; Allen, R.; Owczarek, C.; Bright, M.D.; Kean, S.; Mohd-Noor, A.; Grigoriadis, A.; Elston, T.C.; Hahn, K.M.; et al. An RNAi screen of Rho signalling networks identifies RhoH as a regulator of Rac1 in prostate cancer cell migration. BMC Biol. 2018, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, R.B.; Garg, R.; Collu, F.; D’AGua, B.B.; Menéndez, S.T.; Colomba, A.; Fraternali, F.; Ridley, A.J. RhoBTB1 interacts with ROCKs and inhibits invasion. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 2499–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherfils, J.; Zeghouf, M. Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 269–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigil, D.; Cherfils, J.; Rossman, K.L.; Der, C.J. Ras superfamily GEFs and GAPs: Validated and tractable targets for cancer therapy? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, K.L.; Der, C.J.; Sondek, J. GEF means go: Turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 6, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, P.; Blangy, A. The Evolutionary Landscape of Dbl-Like RhoGEF Families: Adapting Eukaryotic Cells to Environmental Signals. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 1471–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, A.; Côté, J.F.; Barford, D. Structural biology of DOCK-family guanine nucleotide exchange factors. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, C.E.; Southgate, L. The DOCK protein family in vascular development and disease. Angiogenesis 2021, 24, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes-Villagrana, R.D.; García-Jiménez, I.; Vázquez-Prado, J. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho GTPases (RhoGEFs) as oncogenic effectors and strategic therapeutic targets in metastatic cancer. Cell. Signal. 2023, 109, 110749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soisson, S.M.; Nimnual, A.S.; Uy, M.; Bar-Sagi, D.; Kuriyan, J. Crystal Structure of the Dbl and Pleckstrin Homology Domains from the Human Son of Sevenless Protein. Cell 1998, 95, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, Z.; Medina, F.; Liu, M.-Y.; Thomas, C.; Sprang, S.R.; Sternweis, P.C. Activated RhoA binds to the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of PDZ-RhoGEF, a potential site for autoregulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 21070–21081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Azeez, K.R.; Knapp, S.; Fernandes, J.M.; Klussmann, E.; Elkins, J.M. The crystal structure of the RhoA-AKAP-Lbc DH-PH domain complex. Biochem. J. 2014, 464, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, M.A.; Rossman, K.L.; Sondek, J.; Lemmon, M.A. The Dbs PH domain contributes independently to membrane targeting and regulation of guanine nucleotide-exchange activity. Biochem. J. 2006, 400, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffzek, K.; Welti, S. Pleckstrin homology (PH) like domains-versatile modules in protein-protein interaction platforms. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2662–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, I.K.; Tao, J.; Chang, C. The RhoGEF protein Plekhg5 self-associates via its PH domain to regulate apical cell constriction. Mol. Biol. Cell 2024, 35, ar134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Ye, H.; Yao, Y.; Li, H.; Qin, X.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, W.; Xu, M.; Zi, T.; et al. VAV2 exists in extrachromosomal circular DNA and contributes Enzalutamide resistance of prostate cancer via stabilization of AR/ARv7. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 2843–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-T.; Gong, J.; Li, C.-F.; Jang, T.-H.; Chen, W.-L.; Chen, H.-J.; Wang, L.-H. Vav3-rac1 signaling regulates prostate cancer metastasis with elevated Vav3 expression correlating with prostate cancer progression and posttreatment recurrence. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3000–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernards, A. GAPs galore! A survey of putative Ras superfamily GTPase activating proteins in man and Drosophila. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2003, 1603, 47–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.E.; Webb, R.C. Chapter 16—The RhoA/Rho-Kinase Signaling Pathway in Vascular Smooth Muscle Contraction: Biochemistry, Physiology, and Pharmacology. In Comprehensive Hypertension; Lip, G.Y.H., Hall, J.E., Eds.; Mosby: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, J.; Douglas, G.; Wu, C.H.; Burbelo, P.D. Human RhoGAP domain-containing proteins: Structure, function and evolutionary relationships. FEBS Lett. 2002, 528, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarini, M.; Traina, F.; Machado-Neto, J.A.; Barcellos, K.S.; Moreira, Y.B.; Brandão, M.M.; Verjovski-Almeida, S.; Ridley, A.J.; Saad, S.T.O. ARHGAP21 is a RhoGAP for RhoA and RhoC with a role in proliferation and migration of prostate adenocarcinoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2013, 1832, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ménétrey, J.; Perderiset, M.; Cicolari, J.; Dubois, T.; Elkhatib, N.; El Khadali, F.; Franco, M.; Chavrier, P.; Houdusse, A. Structural basis for ARF1-mediated recruitment of ARHGAP21 to Golgi membranes. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 1953–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarini, M.; Assis-Mendonça, G.R.; Machado-Neto, J.A.; Latuf-Filho, P.; Bezerra, S.M.; Vieira, K.P.; Saad, S.T.O. Silencing of ARHGAP21, a Rho GTPase activating protein (RhoGAP), reduces the growth of prostate cancer xenografts in NOD/SCID mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2023, 1870, 119439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, K.; Matsumoto, H.; Hirata, H.; Ueno, K.; Samoto, M.; Mori, J.; Fujii, N.; Kawai, Y.; Inoue, R.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. ARHGAP29 expression may be a novel prognostic factor of cell proliferation and invasion in prostate cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 44, 2735–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Yu, T.; Huang, Y.; Cui, L.; Hong, W. ETS (E26 transformation-specific) up-regulation of the transcriptional co-activator TAZ promotes cell migration and metastasis in prostate cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 9420–9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-Z.; Lv, D.-J.; Wang, C.; Song, X.-L.; Xie, T.; Wang, T.; Li, Z.-M.; Guo, J.-D.; Fu, D.-J.; Li, K.-J.; et al. Hsa_circ_0003258 promotes prostate cancer metastasis by complexing with IGF2BP3 and sponging miR-653-5p. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspenström, P. BAR Domain Proteins Regulate Rho GTPase Signaling. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1111, 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D. miR-769-5p is associated with prostate cancer recurrence and modulates proliferation and apoptosis of cancer cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Chen, X.; Jin, Y.; Lu, J.; Cai, Y.; Wei, O.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.; Wen, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Expression of ARHGAP10 correlates with prognosis of prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 3839–3846. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jaafar, L.; Fakhoury, I.; Saab, S.; El-Hajjar, L.; Abou-Kheir, W.; El-Sibai, M. StarD13 differentially regulates migration and invasion in prostate cancer cells. Hum. Cell 2021, 34, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Qian, X.; Sanchez-Solana, B.; Tripathi, B.K.; Durkin, M.E.; Lowy, D.R. Cancer-Associated Point Mutations in the DLC1 Tumor Suppressor and Other Rho-GAPs Occur Frequently and Are Associated with Decreased Function. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 3568–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.C.; Shih, Y.P.; Lo, S.H. Mutations in the focal adhesion targeting region of deleted in liver cancer-1 attenuate their expression and function. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 7718–7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Popescu, N.C.; Zimonjic, D.B. DLC1 suppresses NF-κB activity in prostate cancer cells due to its stabilizing effect on adherens junctions. Springerplus 2014, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Popescu, N.C.; Zimonjic, D.B. DLC1 interaction with α-catenin stabilizes adherens junctions and enhances DLC1 antioncogenic activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 2145–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Popescu, N.C.; Zimonjic, D.B. DLC1 induces expression of E-cadherin in prostate cancer cells through Rho pathway and suppresses invasion. Oncogene 2014, 33, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.-P.; Liao, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.; Lo, S.H. DLC1 negatively regulates angiogenesis in a paracrine fashion. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 8270–8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mata, R.; Boulter, E.; Burridge, K. The ‘invisible hand’: Regulation of RHO GTPases by RHOGDIs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Kim, J.-T.; Baek, K.E.; Kim, B.-Y.; Lee, H.G. Regulation of Rho GTPases by RhoGDIs in Human Cancers. Cells 2019, 8, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, A.; Cordelières, F.P.; Cherfils, J.; Olofsson, B. RhoGDI3 and RhoG. Small GTPases 2010, 1, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adra, C.N.; Manor, D.; Ko, J.L.; Zhu, S.; Horiuchi, T.; Van Aelst, L.; Cerione, R.A.; Lim, B. RhoGDIγ: A GDP-dissociation inhibitor for Rho proteins with preferential expression in brain and pancreas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 4279–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalcman, G.; Closson, V.; Camonis, J.; Honoré, N.; Rousseau-Merck, M.F.; Tavitian, A.; Olofsson, B. RhoGDI-3 is a new GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI). Identification of a non-cytosolic GDI protein interacting with the small GTP-binding proteins RhoB and RhoG. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 30366–30374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, A.; Amemiya, Y.; Sugar, L.; Nam, R.; Seth, A. Whole-transcriptome analysis reveals established and novel associations with TMPRSS2:ERG fusion in prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 3629–3641. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, T.; Okamura, T.; Nagano, K.; Imai, S.; Abe, Y.; Nabeshi, H.; Yoshikawa, T.; Yoshioka, Y.; Kamada, H.; Tsutsumi, Y.; et al. Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor alpha is associated with cancer metastasis in colon and prostate cancer. Pharmazie 2012, 67, 253–255. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Tummala, R.; Liu, C.; Nadiminty, N.; Lou, W.; Evans, C.P.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, A.C. RhoGDIα suppresses growth and survival of prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2012, 72, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montani, L.; Bausch-Fluck, D.; Domingues, A.F.; Wollscheid, B.; Relvas, J.B. Identification of new interacting partners for atypical Rho GTPases: A SILAC-based approach. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 827, 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Strasser, L. Atypical RhoUV GTPases in development and disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2024, 52, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, R.B.; Ridley, A.J. Rho GTPases: Regulation and roles in cancer cell biology. Small GTPases 2016, 7, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspenström, P. The Role of Fast-Cycling Atypical RHO GTPases in Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, M.; Reis, K.; Aspenström, P. RhoD localization and function is dependent on its GTP/GDP-bound state and unique N-terminal motif. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 97, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal, C.; Favre, G.; Couderc, B.; Salicio, S.; Sixou, S.; Hamilton, A.D.; Sebti, S.M.; Lajoie-Mazenc, I.; Pradines, A. RhoA Prenylation Is Required for Promotion of Cell Growth and Transformation and Cytoskeleton Organization but Not for Induction of Serum Response Element Transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 31001–31008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Mir, L.; Franco, A.; Martín-García, R.; Madrid, M.; Vicente-Soler, J.; Soto, T.; Gacto, M.; Pérez, P.; Cansado, J. Rho2 palmitoylation is required for plasma membrane localization and proper signaling to the fission yeast cell integrity mitogen- activated protein kinase pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 34, 2745–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter-Vann, A.M.; Casey, P.J. Post-prenylation-processing enzymes as new targets in oncogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzat, A.C.; Buss, J.E.; Chenette, E.J.; Weinbaum, C.A.; Shutes, A.; Der, C.J.; Minden, A.; Cox, A.D. Transforming activity of the Rho family GTPase, Wrch-1, a Wnt-regulated Cdc42 homolog, is dependent on a novel carboxyl-terminal palmitoylation motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 33055–33065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Fierke, C.A. Understanding Protein Palmitoylation: Biological Significance and Enzymology. Sci. China Chem. 2011, 54, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, A.; Ponimaskin, E. Lipidation of small GTPase Cdc42 as regulator of its physiological and pathophysiological functions. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1088840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Dong, H.; Li, J. Genetic variants in RhoA and ROCK1 genes are associated with the development, progression and prognosis of prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 19298–19309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goka, E.T.; Lopez, D.T.M.; Lippman, M.E. Hormone-Dependent Prostate Cancers are Dependent on Rac Signaling for Growth and Survival. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.J.; Abba, M.C.; Garcia-Mata, R.; Kazanietz, M.G. P-REX1-Independent, Calcium-Dependent RAC1 Hyperactivation in Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuner, S.E.; Sumbul, F.; Torun, H.; Haliloglu, T. Oncogenic mutations on Rac1 affect global intrinsic dynamics underlying GTP and PAK1 binding. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanapragasam, V.J.; Leung, H.Y.; Pulimood, A.S.; E Neal, D.; Robson, C.N. Expression of RAC 3, a steroid hormone receptor co-activator in prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 85, 1928–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, N.P.; Liu, Y.; Majumder, S.; Warren, M.R.; Parker, C.E.; Mohler, J.L.; Earp, H.S.; Whang, Y.E. Activated Cdc42-associated kinase Ack1 promotes prostate cancer progression via androgen receptor tyrosine phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8438–8443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heemers, H.V. Identification of a RhoA- and SRF-dependent mechanism of androgen action that is associated with prostate cancer progression. Curr. Drug Targets 2013, 14, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schratt, G.; Philippar, U.; Berger, J.; Schwarz, H.; Heidenreich, O.; Nordheim, A. Serum response factor is crucial for actin cytoskeletal organization and focal adhesion assembly in embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 156, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkadakrishnan, V.B.; DePriest, A.D.; Kumari, S.; Senapati, D.; Ben-Salem, S.; Su, Y.; Mudduluru, G.; Hu, Q.; Cortes, E.; Pop, E.; et al. Protein Kinase N1 control of androgen-responsive serum response factor action provides rationale for novel prostate cancer treatment strategy. Oncogene 2019, 38, 4496–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Stolz, D.B.; Guo, F.; Ross, M.A.; Watkins, S.C.; Tan, B.J.; Qi, R.Z.; Manser, E.; Li, Q.T.; Bay, B.H.; et al. Signaling via a novel integral plasma membrane pool of a serine/threonine protein kinase PRK1 in mammalian cells. Faseb J. 2004, 18, 1722–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, E.; Müller, J.M.; Ferrari, S.; Buettner, R.; Schüle, R. A novel inducible transactivation domain in the androgen receptor: Implications for PRK in prostate cancer. Embo J. 2003, 22, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Han, S.J.; Tsai, S.Y.; DeMayo, F.J.; Xu, J.; Tsai, M.-J.; O’Malley, B.W. Roles of steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-1 and transcriptional intermediary factor (TIF) 2 in androgen receptor activity in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9487–9492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D.L.; Mize, G.J.; Takayama, T.K. Protease-activated receptor mediated RhoA signaling and cytoskeletal reorganization in LNCaP cells. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.-D.; Yang, Q.; Ceniccola, K.; Bianco, F.; Andrawis, R.; Jarrett, T.; Frazier, H.; Patierno, S.R.; Lee, N.H. Androgen receptor-target genes in african american prostate cancer disparities. Prostate Cancer 2013, 2013, 763569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, O.Y.; Fu, G.; Ismail, A.; Srinivasan, S.; Cao, X.; Tu, Y.; Lu, S.; Nawaz, Z. Multifunction steroid receptor coactivator, E6-associated protein, is involved in development of the prostate gland. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhang, P.; Chen, T.; Yang, M. Clinical feature and gene expression analysis in low prostate-specific antigen, high-grade prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0321728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Nawaz, Z. E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, E6-associated protein (E6-AP) regulates PI3K-Akt signaling and prostate cell growth. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 2011, 1809, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donato, M.; Bilancio, A.; Auricchio, F.; Castoria, G.; Migliaccio, A. Androgens and NGF Mediate the Neurite-Outgrowth through Inactivation of RhoA. Cells 2023, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizopoulos, K.; Dimas, K.; Papadopoulou, N.; Schmidt, E.-M.; Tsapara, A.; Alkahtani, S.; Honisch, S.; Prousis, K.C.; Alarifi, S.; Calogeropoulou, T.; et al. Functional characterization and anti-cancer action of the clinical phase II cardiac Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor istaroxime: In vitro and in vivo properties and cross talk with the membrane androgen receptor. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 24415–24428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isayeva, T.; Moore, L.D.; Chanda, D.; Chen, D.; Ponnazhagan, S. Tumoristatic effects of endostatin in prostate cancer is dependent on androgen receptor status. Prostate 2009, 69, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- González-Montelongo, M.C.; Marín, R.; Gómez, T.; Marrero-Alonso, J.; Díaz, M. Androgens induce nongenomic stimulation of colonic contractile activity through induction of calcium sensitization and phosphorylation of LC20 and CPI-17. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Kunz, S.; Davis, K.; Roberts, J.; Martin, G.; Demetriou, M.C.; Sroka, T.C.; Cress, A.E.; Miesfeld, R.L. Androgen control of cell proliferation and cytoskeletal reorganization in human fibrosarcoma cells: Role of RhoB signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissenrieder, J.S.; Reilly, J.E.; Neighbors, J.D.; Hohl, R.J. Inhibiting geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthesis reduces nuclear androgen receptor signaling and neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer cell models. Prostate 2019, 79, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannelli, P.; Di Donato, M.; Auricchio, F.; Castoria, G. Analysis of the androgen receptor/filamin a complex in stromal cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1204, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Castoria, G.; Giovannelli, P.; Di Donato, M.; Ciociola, A.; Hayashi, R.; Bernal, F.; Appella, E.; Auricchio, F.; Migliaccio, A. Role of non-genomic androgen signalling in suppressing proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosarcoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakonstanti, E.A.; Kampa, M.; Castanas, E.; Stournaras, C. A rapid, nongenomic, signaling pathway regulates the actin reorganization induced by activation of membrane testosterone receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.R.; Ramos, S.M.; Ko, A.; Masiello, D.; Swanson, K.D.; Lu, M.L.; Balk, S.P. AR and ER interaction with a p21-activated kinase (PAK6). Mol. Endocrinol. 2002, 16, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schrantz, N.; Correia, J.d.S.; Fowler, B.; Ge, Q.; Sun, Z.; Bokoch, G.M. Mechanism of p21-activated kinase 6-mediated inhibition of androgen receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 1922–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Park, C.K.; Choi, Y.-D.; Cho, N.H.; Lee, J.; Cho, K.S. Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer Is Sensitive to CDC42-PAK7 Kinase Inhibition. Biomedicines 2022, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujar, M.K.; Vastrad, B.; Vastrad, C. Integrative Analyses of Genes Associated with Subcutaneous Insulin Resistance. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, S.O.; Fahrenholtz, C.D.; Burnstein, K.L. Vav3 enhances androgen receptor splice variant activity and is critical for castration-resistant prostate cancer growth and survival. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 1967–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, A.; Lee, K.; Wang, L.-H.; Revelo, M. Vav3 oncogene is overexpressed and regulates cell growth and androgen receptor activity in human prostate cancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 2315–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Mo, J.Q.; Hu, Q.; Boivin, G.; Levin, L.; Lu, S.; Yang, D.; Dong, Z. Targeted overexpression of vav3 oncogene in prostatic epithelium induces nonbacterial prostatitis and prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 6396–6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, T.; Yamasaki, M.; Hirai, K.; Inoue, T.; Sato, R.; Matsuura, K.; Moriyama, M.; Sato, F.; Mimata, H. Targeting the Vav3 oncogene enhances docetaxel-induced apoptosis through the inhibition of androgen receptor phosphorylation in LNCaP prostate cancer cells under chronic hypoxia. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M.; Peinetti, N.; Kazanietz, M.G.; Burnstein, K.L. RAC1 signaling in prostate cancer: VAV GEFs take center stage. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1658639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.; Lyons, L.S.; Fahrenholtz, C.D.; Wu, F.; Farooq, A.; Balkan, W.; Burnstein, K.L. A novel nuclear role for the Vav3 nucleotide exchange factor in androgen receptor coactivation in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2012, 31, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Dong, Z.; Lu, S. The molecular mechanism of Vav3 oncogene on upregulation of androgen receptor activity in prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2010, 36, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lyons, L.S.; Burnstein, K.L. Vav3, a Rho GTPase guanine nucleotide exchange factor, increases during progression to androgen independence in prostate cancer cells and potentiates androgen receptor transcriptional activity. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Magani, F.; Peacock, S.O.; Rice, M.A.; Martinez, M.J.; Greene, A.M.; Magani, P.S.; Lyles, R.; Weitz, J.R.; Burnstein, K.L. Targeting AR Variant-Coactivator Interactions to Exploit Prostate Cancer Vulnerabilities. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-Y.C.; Carpenter, E.S.; Takeuchi, K.K.; Halbrook, C.J.; Peverley, L.V.; Bien, H.; Hall, J.C.; DelGiorno, K.E.; Pal, D.; Song, Y.; et al. PI3K Regulation of RAC1 Is Required for KRAS-Induced Pancreatic Tumorigenesis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 1405–1416.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shao, Y.; Wei, W.; Zhu, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Tian, H.; Sun, G.; Niu, Y.; et al. Androgen deprivation restores ARHGEF2 to promote neuroendocrine differentiation of prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.; Hemkemeyer, S.A.; Alimajstorovic, Z.; Bowers, C.; Eskandarpour, M.; Greenwood, J.; Calder, V.; Chan, A.W.E.; Gane, P.J.; Selwood, D.L.; et al. Therapeutic Validation of GEF-H1 Using a De Novo Designed Inhibitor in Models of Retinal Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.; Neves, A.; Vecchi, L.; Souza, T.; Vaz, E.; Mota, S.; Nicolau-Junior, N.; Goulart, L.; Araújo, T. Rho GTPase activating protein 21-mediated regulation of prostate cancer associated 3 gene in prostate cancer cell. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2024, 57, e13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, C.; Tummala, R.; Nadiminty, N.; Lou, W.; Gao, A.C. RhoGDIα downregulates androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2013, 73, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Classification | Rho Subfamily | Subfamily Members # | Molecular Weight (kDa) * | Amino Acids * | Base Length * | Chromosome * | Exons ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Rho | RhoA | 21.8 | 193 | 53,860 | 3p21.31 | 7 |

| RhoB | 22.1 | 196 | 2367 | 2p24.1 | 1 | ||

| RhoC | 22 | 193 | 6308 | 1p13.2 | 7 | ||

| Rac | Rac1 | 21.5 | 192 | 29,441 | 7p22.1 | 7 | |

| Rac2 | 21.4 | 192 | 34,325 | 22q13.1 | 8 | ||

| Rac3 | 21.4 | 192 | 2527 | 17q25.3 | 6 | ||

| RhoG | 21.3 | 191 | 13,982 | 11p15.4 | 2 | ||

| Cdc42 | Cdc42 | 21.3 | 191 | 48,734 | 1p36.12 | 8 | |

| RhoJ/TCL | 23.8 | 214 | 89,395 | 14q23.2 | 6 | ||

| RhoQ/TC10 | 22.7 | 205 | 42,883 | 2p21 | 6 | ||

| Atypical | Rif | RhoD | 23.5 | 210 | 15,171 | 11q13.2 | 4 |

| RhoF/Rif | 23.6 | 211 | 25,650 | 12q24.31 | 5 | ||

| Rnd | Rnd1 | 26.1 | 232 | 8726 | 12q13.12 | 5 | |

| Rnd2 | 25.4 | 227 | 6811 | 17q21.31 | 7 | ||

| Rnd3/RhoE | 27.4 | 244 | 19,503 | 2q23.3 | 6 | ||

| Wrch | RhoU/Wrch1 | 28.2 | 258 | 102,023 | 1q42.13 | 7 | |

| RhoV/Wrch2/Chp | 26.2 | 236 | 2021 | 15q15.1 | 3 | ||

| RhoH | RhoH/TTF | 21.3 | 192 | 55,957 | 4p14 | 13 | |

| RhoBTB | RhoBTB1 | 79.4 | 696 | 141,108 | 10q21.2 | 24 | |

| RhoBTB2 | 82.6 | 727 | 69,697 | 8p21.3 | 16 |

| Classification | Subfamily | Subfamily Members | Major Function * | Lipidation † |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Rho | RhoA | tumor cell proliferation and metastasis, cytoskeletal organization | GG |

| RhoB | mediates apoptosis, tumor suppression, protein trafficking | GG, F, P | ||

| RhoC | assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers | GG | ||

| Rac | Rac1 | cell growth, cytoskeletal reorganization, and the activation of protein kinases | GG | |

| Rac2 | secretion, phagocytosis, and cell polarization | GG | ||

| Rac3 | cell spreading, actin-based protusions (lamellipodia, membrane ruffles) | GG | ||

| RhoG | lamellipodium formation and cell migration | GG | ||

| Cdc42 | Cdc42 | actin polymerization, epithelial cell polarization, formation of filopodia | P, GG | |

| RhoJ/TCL | focal adhesions in endothelial cells may regulate angiogenesis | P, GG | ||

| RhoQ/TC10 | sarcomere assembly, epithelial cell polarization, epithelial cell polarization | P, GG | ||

| Atypical | Rif | RhoD | endosome dynamics, actin cytoskeleton reorganization, membrane transport | GG |

| RhoF/Rif | actin filament organization | GG | ||

| Rnd | Rnd1 | response to extracellular growth factors | F | |

| Rnd2 | regulation of neuronal morphology and endosomal trafficking | F | ||

| Rnd3/RhoE | negative regulator of cytoskeletal organization leading to loss of adhesion | F | ||

| Wrch | RhoU/Wrch1 | induce filopodium formation and stress fiber dissolution, regulate the actin cytoskeleton, adhesion turnover and increase cell migration, regulation of cell morphology, cytoskeletal organization, and cell proliferation | P | |

| RhoV/Wrch2/Chp | control of the actin cytoskeleton | P | ||

| RhoH | RhoH/TTF | negative regulator of cell growth and survival | GG | |

| RhoBTB | RhoBTB1 | organization of the actin filament | Nil | |

| RhoBTB2 | candidate tumor suppressor, regulates mitotic cell division | Nil |

| Classification | Rho Subfamily | Subfamily Members | Downstream Targets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Established | Others (Binding Partners) * | |||

| Classical | Rho | RhoA | ROCK, Dia, LIMK | ARHGAP1, ARHGAP5, ARHGDIA, ARHGEF11, ARHGEF12, ARHGEF3, CIT, DGKQ, DIAPH1, GEFT, ITPR1, KCNA2, KTN1, MAP3K1, PKN2, PLCG1, Phospholipase D1, protein kinase N1, RAP1GDS1, RICS, TRIO, and TRPC1 |

| RhoB | PRK1, Sema3A, plexinA4, and Src | NF-κB, ROCK1, and EGFR phosphatase PTPRH | ||

| RhoC | ROCK, Dia, FMNL3 | IQGAP1, MMP9, the MAPK pathway, Notch1, and PI3K/AKT | ||

| Rac | Rac1 | PAK1, JNK1/2, MLK2/3, PI3K/Akt, NF-kB | Scar/WAVE complex, LIMK/cofilin pathway, and mTOR | |

| Rac2 | p67phox, NOX2, PAK1, Bcl-xL | PI 5-kinase | ||

| Rac3 | GIT1, PAK1, PI 5-kinase, E-cadherin | CCND1, MYC, and TFDP1 | ||

| RhoG | Rac1, DOCK/ELMO2, Kinectin, MLK3, PLD1, Filamin, SGEF, EphA2 | |||

| Cdc42 | Cdc42 | PAK, MLK, WASP, IQGAP, PI3K, PAR6, p70S6K, Akt, PIP2, PIP3 | CD11b, microtubules, and cell adhesion molecules | |

| RhoJ/TCL | PAK, ERK, RAC1, MOESIN | PlexinD1 and VEGFR2 | ||

| RhoQ/TC10 | ROCK, PAK | WASP, RACK1, LIMK, MLCK, MLCP | ||

| Atypical | Rif | RhoD | ROCK, mDia, PAK | |

| RhoF/Rif | ROCK | Actin binding proteins, cell adhesion and migration proteins, cell polarization proteins, Wnt/b-catenin signaling | ||

| Rnd | Rnd1 | ERK, p53, Notch, Plexin | Proteins involved in innate immunity | |

| Rnd2 | pragmin, p38 | |||

| Rnd3/RhoE | ROCK1, PLEKHG5, ARHGAP5, UBXD5, NF-kB/p65 | |||

| Wrch | RhoU/Wrch1 | PAK, IQGAP1, Rhotekin | ||

| RhoV/Wrch2/Chp | PAK1, JNK, AKT, ERK, EGFR | |||

| RhoH | RhoH/TTF | BCL-6, BLIMP-1, KAISO, ROCK1, PKCα | Inflammatory neutrophil functions | |

| RhoBTB | RhoBTB1 | PDE5, Cullin-3 | Actin polymerization, METTL7B, METTL7A | |

| RhoBTB2 | LKB1, HIPPO, CXCL14 | |||

| Subfamily Members | Expression in Prostate Cancer vs. Non-Tumor Tissue ‡ | Hazard Ratio (Disease Free Survival) ** | Correlation with Androgen Receptor Expression † |

|---|---|---|---|

| RhoA | Increased | 1.3 | 0.48 * |

| RhoB | Decreased * | 0.85 | 0.013 |

| RhoC | Increased | 1.8 * | 0.042 |

| Rac1 | Increased | 1.1 | 0.36 * |

| Rac2 | No change | 1.6 * | 0.01 |

| Rac3 | Increased * | 1.3 | −0.00066 |

| RhoG | No change | 1.3 | −0.13 * |

| Cdc42 | Increased | 1.2 | 0.53 * |

| RhoJ/TCL | Decreased * | 1.1 | 0.12 * |

| RhoQ/TC10 | Decreased | 0.84 | 0.39 * |

| RhoD | Increased | 1.2 | −0.15 * |

| RhoF/Rif | Decreased | 1.9 * | 0.13 * |

| Rnd1 | No change | 0.99 | -0.02 |

| Rnd2 | Decreased * | 0.75 | −0.2 * |

| Rnd3/RhoE | Decreased * | 0.76 | -0.029 |

| RhoU/Wrch1 | Increased | 1.5 * | 0.27 * |

| RhoV/Wrch2/Chp | No change | 1.1 | −0.074 |

| RhoH/TTF | Increased | 1.5 * | 0.13 * |

| RhoBTB1 | Decreased * | 1.4 | 0.28 * |

| RhoBTB2 | Decreased | 0.83 | 0.21 * |

| Name of Drug | Target | How It Affects Rho Small GTPases |

|---|---|---|

| Y-27632 dihydrochloride | ROCK1/ROCK2, c-myc | inhibits signaling downstream of RhoA, RhoC |

| CCG-1423 | Rho/SRF pathway inhibitor | inhibits transcriptional activity downstream of SRF |

| Rhosin hydrochloride | RhoA, RhoC | inhibits binding of Rho GTPase with the GEF LARG |

| NSC126188 | RhoB inducer | activates RhoB transcription |

| RV001 | RhoC (vaccination) | immune responses |

| NSC 23766 | Rac1 | inhibits Rac1 binding by the Rac-specific GEF Trio or Tiam1 |

| 1A-116 | Rac1 | anti-tumor activity |

| Z62954982 | Rac1 | preventing Rac1 from interacting with Tiam1 |

| EHT 1864 2HCl | pan-Rac | directly binding to and inhibiting Rac1, Rac1b, Rac2, and Rac3 |

| EHop-016 | Rac1, Rac3 | inhibits the association of Vav2 with Rac GTPase |

| Azathioprine(BW 57-322) | rac1 | immunosuppressive drug. |

| MBQ-167 | Rac1/Cdc42 | ongoing Phase I clinical trial |

| ZCL278 | Cdc42 | targeting Cdc42–intersectin interaction |

| MLS-573151 | Cdc42 | blocking the binding of GTP to Cdc42 |

| CID44216842 | Cdc42 | guanine nucleotide binding inhibitor |

| ML141 (CID-2950007) | Cdc42, Rac1, Rab2, Rab7 | potent, selective, and reversible non-competitive inhibitor of Cdc42 GTPase |

| ARN25062 | RhoJ/Cdc42 | inhibits S6 phosphorylation and MAPK activation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hairston, D.W.S.; Mudryj, M.; Ghosh, P.M. Rho Small GTPase Family in Androgen-Regulated Prostate Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cancers 2025, 17, 3680. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223680

Hairston DWS, Mudryj M, Ghosh PM. Rho Small GTPase Family in Androgen-Regulated Prostate Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cancers. 2025; 17(22):3680. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223680

Chicago/Turabian StyleHairston, Dontrel William Spencer, Maria Mudryj, and Paramita Mitra Ghosh. 2025. "Rho Small GTPase Family in Androgen-Regulated Prostate Cancer Progression and Metastasis" Cancers 17, no. 22: 3680. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223680

APA StyleHairston, D. W. S., Mudryj, M., & Ghosh, P. M. (2025). Rho Small GTPase Family in Androgen-Regulated Prostate Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cancers, 17(22), 3680. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223680