Associations Between Physical Activity, Fitness, Perceived Health, Chronic Disease and Mortality in Adult Survivors of Childhood and Young Adult Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Scoping Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

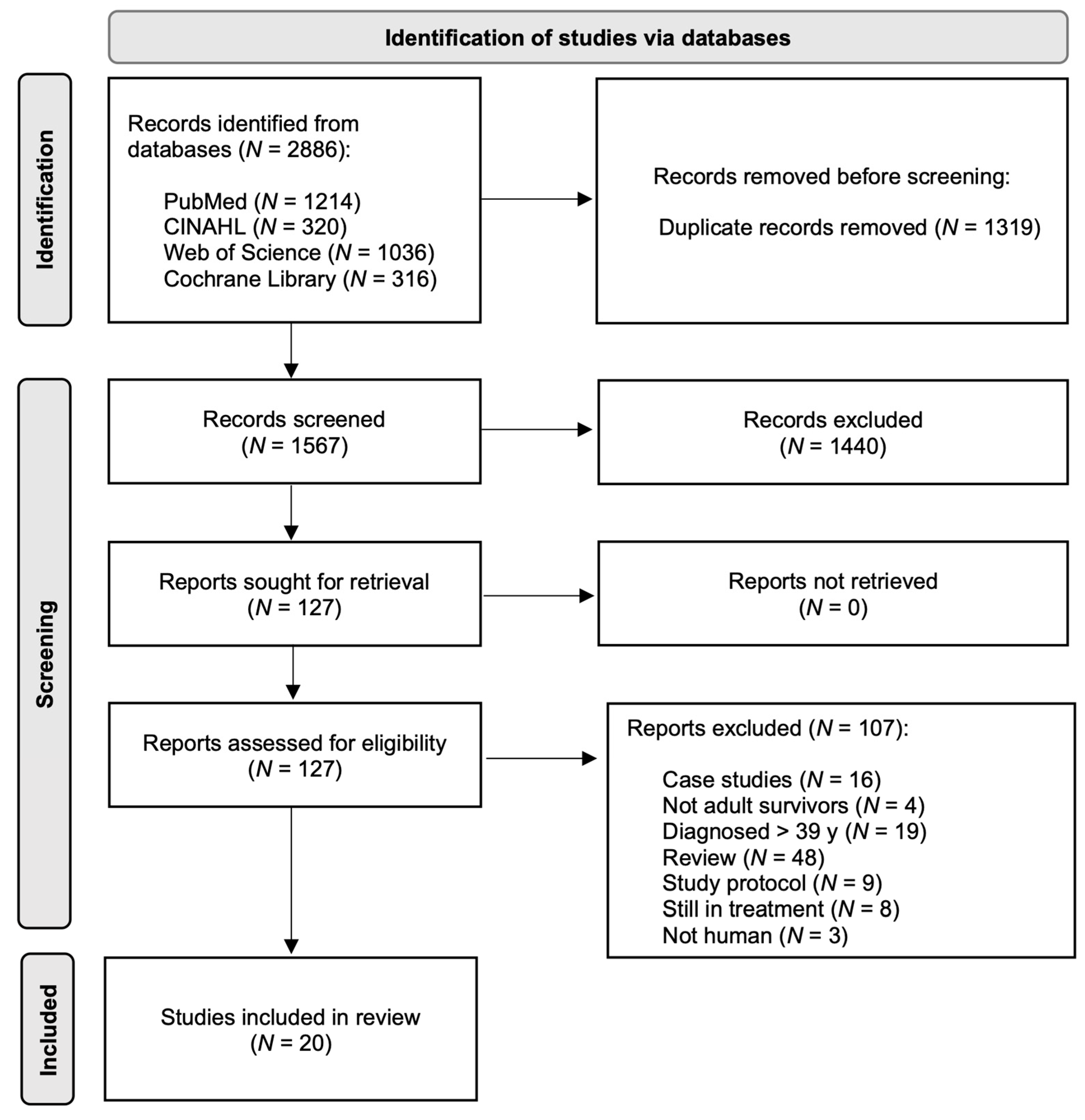

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening Data Extraction

2.4. Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Physical Activity

3.3. Fitness

3.4. Body Composition

3.5. Autonomic Dysfunction

3.6. Associations of Treatment with Poor Fitness, Physical Inactivity, Body Composition and Autonomic Dysfunctions

3.7. Associations of Fitness, Physical Activity and Autonomic Dysfunction with Chronic Disease and/or Mortality

3.8. QoL and Fatigue

4. Discussion

4.1. Possible Mechanisms for Impairments and Chronic Health Conditions in Adult Survivors of Childhood and Young Adult Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

4.2. Possible Mechanisms for PA, Fitness, Perceived Health, Chronic Disease Associated with Mortality in Adult Survivors of Childhood and Young Adult Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

4.3. Interventions to Decrease the Risk of Premature Chronic Health Conditions and/or Mortality

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Bpm | Beats per minute |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CPET | Cardiopulmonary exercise testing |

| CCSS | Childhood Cancer Survivor Study |

| CHCs | Chronic health conditions |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DXA | Dual X-ray Absorbtiometry |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| HL | Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| Kg | Kilogram |

| MmHg | Millimeters of mercury |

| Nm | Newton meters |

| PA | Physical activity |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RT | Radiation therapy |

| RHR | Resting heart rate |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| 6MWT | Six-minute walk distance test |

| SJLIFE | St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SDS | Symptom distress scale |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, G.T.; Liu, Q.; Yasui, Y.; Neglia, J.P.; Leisenring, W.; Robison, L.L.; Mertens, A.C. Late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: A summary from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 2328–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N.S.; Mulrooney, D.A.; Williams, A.M.; Liu, W.; Khan, R.B.; Ehrhardt, M.J.; Folse, T.; Krasin, M.; Srivastava, D.K.; Ness, K.K.; et al. Neurocognitive impairment associated with chronic morbidity in long-term survivors of Hodgkin Lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 7270–7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulrooney, D.A.; Armstrong, G.T.; Huang, S.; Ness, K.K.; Ehrhardt, M.J.; Joshi, V.M.; Plana, J.C.; Soliman, E.Z.; Green, D.M.; Srivastava, D.; et al. Cardiac Outcomes in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer Exposed to Cardiotoxic Therapy: A Cross-sectional Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 164, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nimwegen, F.A.; Schaapveld, M.; Janus, C.P.; Krol, A.D.; Petersen, E.J.; Raemaekers, J.M.; Kok, W.E.; Aleman, B.M.; van Leeuwen, F.E. Cardiovascular disease after Hodgkin lymphoma treatment: 40-year disease risk. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakta, N.; Liu, Q.; Yeo, F.; Baassiri, M.; Ehrhardt, M.J.; Srivastava, D.K.; Metzger, M.L.; Krasin, M.J.; Ness, K.K.; Hudson, M.M.; et al. Cumulative burden of cardiovascular morbidity in paediatric, adolescent, and young adult survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: An analysis from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeffinger, K.C.; Stratton, K.L.; Hudson, M.M.; Leisenring, W.M.; Henderson, T.O.; Howell, R.M.; Wolden, S.L.; Constine, L.S.; Diller, L.R.; Sklar, C.A.; et al. Impact of Risk-Adapted Therapy for Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma on Risk of Long-Term Morbidity: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2266–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklar, C.; Whitton, J.; Mertens, A.; Stovall, M.; Green, D.; Marina, N.; Greffe, B.; Wolden, S.; Robison, L. Abnormalities of the thyroid in survivors of Hodgkin’s disease: Data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 3227–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beek, R.D.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Laven, J.S.; de Jong, F.H.; Themmen, A.P.; Hakvoort-Cammel, F.G.; van den Bos, C.; van den Berg, H.; Pieters, R.; de Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S.M. Anti-Mullerian hormone is a sensitive serum marker for gonadal function in women treated for Hodgkin’s lymphoma during childhood. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 3869–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz, A.; Tayfun, T.; Citak, E.C.; Karadeniz, C.; Tatlicioglu, T.; Boyunaga, O.; Bora, H. Long-term pulmonary function in survivors of childhood Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2007, 49, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, B.; Kadan-Lottick, N.S.; Roberts, K.B.; Wang, R.; Demsky, C.; Kupfer, G.M.; Cooper, D.; Seropian, S.; Ma, X. Patterns of subsequent malignancies after Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adults. Br. J. Haematol. 2012, 158, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulrooney, D.A.; Ness, K.K.; Neglia, J.P.; Whitton, J.A.; Green, D.M.; Zeltzer, L.K.; Robison, L.L.; Mertens, A.C. Fatigue and sleep disturbance in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study (CCSS). Sleep 2008, 31, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, I.C.; Brinkman, T.M.; Armstrong, G.T.; Leisenring, W.; Robison, L.L.; Krull, K.R. Emotional distress impacts quality of life evaluation: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, C.F.; Hooke, M.C.; Friedman, D.L.; Campbell, K.; Withycombe, J.; Schwartz, C.L.; Kelly, K.; Meza, J. Exercise and Fatigue in Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2015, 4, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wogksch, M.D.; Goodenough, C.G.; Finch, E.R.; Partin, R.E.; Ness, K.K. Physical activity and fitness in childhood cancer survivors: A scoping review. Aging Cancer 2021, 2, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.C.; Lee, I.M.; Weiderpass, E.; Campbell, P.T.; Sampson, J.N.; Kitahara, C.M.; Keadle, S.K.; Arem, H.; Berrington de Gonzalez, A.; Hartge, P.; et al. Association of Leisure-Time Physical Activity with Risk of 26 Types of Cancer in 1.44 Million Adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, C.E.; Moore, S.C.; Arem, H.; Cook, M.B.; Trabert, B.; Håkansson, N.; Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A.; Gapstur, S.M.; Lynch, B.M.; et al. Amount and Intensity of Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Lower Cancer Risk. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.N.; Clare, P.J.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Del Pozo Cruz, B.; Lee, I.M.; Stamatakis, E. Vigorous physical activity, incident heart disease, and cancer: How little is enough? Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 4801–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, S.; Hamaue, Y.; Fukushima, T.; Tanaka, T.; Fu, J.B.; Nakano, J. Effect of Exercise on Mortality and Recurrence in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 1534735420917462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedenreich, C.M.; Stone, C.R.; Cheung, W.Y.; Hayes, S.C. Physical Activity and Mortality in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019, 4, pkz080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arem, H.; Moore, S.C.; Patel, A.; Hartge, P.; Berrington de Gonzalez, A.; Visvanathan, K.; Campbell, P.T.; Freedman, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Adami, H.O.; et al. Leisure time physical activity and mortality: A detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.; Feito, Y.; Fountaine, C.; Roy, B.A. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription 9th Ed. 2014. J. Can. Chiropr. Assoc. 2014, 58, 328. [Google Scholar]

- García-Hermoso, A.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B.; Lee, D.C.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Muscular Strength as a Predictor of All-Cause Mortality in an Apparently Healthy Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Data from Approximately 2 Million Men and Women. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 2100–2113.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzatvar, Y.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Sáez de Asteasu, M.L.; Martínez-Velilla, N.; Zambom-Ferraresi, F.; Izquierdo, M.; García-Hermoso, A. Physical Function and All-Cause Mortality in Older Adults Diagnosed with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekblom-Bak, E.; Bojsen-Møller, E.; Wallin, P.; Paulsson, S.; Lindwall, M.; Rundqvist, H.; Bolam, K.A. Association Between Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Cancer Incidence and Cancer-Specific Mortality of Colon, Lung, and Prostate Cancer Among Swedish Men. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2321102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.A.G.; Knight, J.A.; Sutradhar, R.; Brooks, J.D. Association between estimated cardiorespiratory fitness and breast cancer: A prospective cohort study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Mirzaei Salehabadi, S.; Xing, M.; Phillips, N.S.; Ehrhardt, M.J.; Howell, R.; Yasui, Y.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Gibson, T.; Chow, E.J.; et al. Modifiable risk factors for neurocognitive and psychosocial problems after Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2022, 139, 3073–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, F.D.; Bottaro, M.; de Oliveira Valeriano, R.; Cruz, L.; Battaglini, C.L.; Vieira, C.A.; de Oliveira, R.J. Cancer-Related Fatigue and Muscle Quality in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Survivors. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.W.; Liu, Q.; Armstrong, G.T.; Ness, K.K.; Yasui, Y.; Devine, K.; Tonorezos, E.; Soares-Miranda, L.; Sklar, C.A.; Douglas, P.S.; et al. Exercise and risk of major cardiovascular events in adult survivors of childhood hodgkin lymphoma: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3643–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldervoll, L.M.; Loge, J.H.; Kaasa, S.; Lydersen, S.; Hjermstad, M.J.; Thorsen, L.; Holte, H., Jr.; Jacobsen, A.B.; Fosså, S.D. Physical activity in Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors with and without chronic fatigue compared with the general population—A cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer 2007, 7, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemelaar, J.C.; Krol, A.D.G.; Louwerens, M.; Beeres, S.L.M.A.; Holman, E.R.; Schalij, M.J.; Louisa Antoni, M. Elevated resting heart rate is a marker of subclinical left ventricular dysfunction in hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2021, 35, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, R.; Gauvreau, K.; Vinograd, C.; Yamada, J.M.; Mangano, C.; Ng, A.K.; Alexander, M.E.; Chen, M.H. Vo2peak in Adult Survivors of Hodgkin Lymphoma: Rate of Decline, Sex Differences, and Cardiovascular Events. JACC CardioOncol. 2021, 3, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, A.K.; Li, S.; Recklitis, C.; Neuberg, D.; Chakrabarti, S.; Silver, B.; Diller, L. A comparison between long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease and their siblings on fatigue level and factors predicting for increased fatigue. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 1949–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Colan, S.D.; Tarbell, N.J.; Treves, S.T.; Diller, L.; Greenbaum, N.; Mauch, P.; Lipshultz, S.E. Cardiovascular status in long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease treated with chest radiotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 3139–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadota, R.P.; Burgert, E.O., Jr.; Driscoll, D.J.; Evans, R.G.; Gilchrist, G.S. Cardiopulmonary function in long-term survivors of childhood Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A pilot study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1988, 63, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacyildiz, N.; Cakmak, H.M.; Unal, E.; Dincaslan, H.; Tanyıldız, G.; Özdemir, S.I.; Kartal, Ö.; Yılmaz, Y.; Yavuz, G.; Kuzu, I. Evaluation of late effects during a 21-year follow-up of pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma survivors: Experience of a pediatric cancer center in Turkey, as a developing country model. Indian J. Cancer 2024, 61, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtbaeumer, N.; Müller, H.; Goergen, H.; Kreissl, S.; Borchmann, P.; Mayer, A. The interplay between cancer-related fatigue and functional health in Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wogksch, M.D.; Howell, C.R.; Wilson, C.L.; Partin, R.E.; Ehrhardt, M.J.; Krull, K.R.; Brinkman, T.M.; Mulrooney, D.A.; Hudson, M.M.; Robison, L.L.; et al. Physical fitness in survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma: A report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rach, A.M.; Crabtree, V.M.; Brinkman, T.M.; Zeltzer, L.; Marchak, J.G.; Srivastava, D.; Tynes, B.; Lai, J.S.; Robison, L.L.; Armstrong, G.T.; et al. Predictors of fatigue and poor sleep in adult survivors of childhood Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, K.; Cooley, M.E.; McDermott, K.; Fawcett, J. Health-related quality of life after treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma in young adults. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2013, 40, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calaminus, G.; Dörffel, W.; Baust, K.; Teske, C.; Riepenhausen, M.; Brämswig, J.; Flechtner, H.H.; Singer, S.; Hinz, A.; Schellong, G. Quality of life in long-term survivors following treatment for Hodgkin’s disease during childhood and adolescence in the German multicentre studies between 1978 and 2002. Support Care Cancer 2014, 22, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen-Segarceanu, E.M.; Dorresteijn, L.D.; Pillen, S.; Biesma, D.H.; Vogels, O.J.; van Alfen, N. Progressive muscle atrophy and weakness after treatment by mantle field radiotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 82, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjermstad, M.J.; Oldervoll, L.; Fosså, S.D.; Holte, H.; Jacobsen, A.B.; Loge, J.H. Quality of life in long-term Hodgkin’s disease survivors with chronic fatigue. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaste, S.C.; Metzger, M.L.; Minhas, A.; Xiong, Z.; Rai, S.N.; Ness, K.K.; Hudson, M.M. Pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma survivors at negligible risk for significant bone mineral density deficits. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2009, 52, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beek, R.D.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Hakvoort-Cammel, F.G.; van den Bos, C.; van der Pal, H.J.; Krenning, E.P.; de Rijke, Y.B.; Pieters, R.; de Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S.M. Bone mineral density, growth, and thyroid function in long-term survivors of pediatric Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with chemotherapy only. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 1904–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groarke, J.D.; Tanguturi, V.K.; Hainer, J.; Klein, J.; Moslehi, J.J.; Ng, A.; Forman, D.E.; Di Carli, M.F.; Nohria, A. Abnormal exercise response in long-term survivors of hodgkin lymphoma treated with thoracic irradiation: Evidence of cardiac autonomic dysfunction and impact on outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, L.; Gibson, T.M.; Pui, C.H.; Joshi, V.; Partin, R.E.; Green, D.M.; Lanctot, J.Q.; Howell, C.R.; Mulrooney, D.A.; Armstrong, G.T.; et al. Cardiac autonomic dysfunction in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: The St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Martin, C.; Burton, M.; Walters, S.; Collins, K.; Wyld, L. Quality of life versus length of life considerations in cancer patients: A systematic literature review. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 1367–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediebah, D.E.; Quinten, C.; Coens, C.; Ringash, J.; Dancey, J.; Zikos, E.; Gotay, C.; Brundage, M.; Tu, D.; Flechtner, H.H.; et al. Quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: A pooled analysis of individual patient data from canadian cancer trials group clinical trials. Cancer 2018, 124, 3409–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipshultz, S.E.; Adams, M.J.; Colan, S.D.; Constine, L.S.; Herman, E.H.; Hsu, D.T.; Hudson, M.M.; Kremer, L.C.; Landy, D.C.; Miller, T.L.; et al. Long-term cardiovascular toxicity in children, adolescents, and young adults who receive cancer therapy: Pathophysiology, course, monitoring, management, prevention, and research directions: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 128, 1927–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuranno, L.; Ient, J.; De Ruysscher, D.; Vooijs, M.A. Radiation-Induced Lung Injury (RILI). Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanania, A.N.; Mainwaring, W.; Ghebre, Y.T.; Hanania, N.A.; Ludwig, M. Radiation-Induced Lung Injury: Assessment and Management. Chest 2019, 156, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ell, P.; Martin, J.M.; Cehic, D.A.; Ngo, D.T.M.; Sverdlov, A.L. Cardiotoxicity of Radiation Therapy: Mechanisms, Management, and Mitigation. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2021, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Cheng, Y. The cardiac toxicity of radiotherapy—A review of characteristics, mechanisms, diagnosis, and prevention. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2021, 97, 11333–11340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijerathne, H.; Langston, J.C.; Yang, Q.; Sun, S.; Miyamoto, C.; Kilpatrick, L.E.; Kiani, M.F. Mechanisms of radiation-induced endothelium damage: Emerging models and technologies. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 158, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, K.K.; Plana, J.C.; Joshi, V.M.; Luepker, R.V.; Durand, J.B.; Green, D.M.; Partin, R.E.; Santucci, A.K.; Howell, R.M.; Srivastava, D.K.; et al. Exercise Intolerance, Mortality, and Organ System Impairment in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, J.M.; New, J.; Hamilton, C.D.; Lominska, C.; Shnayder, Y.; Thomas, S.M. Radiation-induced fibrosis: Mechanisms and implications for therapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 141, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, E.K.; Zhou, Y.; Chemaitilly, W.; Panetta, J.C.; Ness, K.K.; Kaste, S.C.; Cheng, C.; Relling, M.V.; Pui, C.H.; Inaba, H. Changes in body mass index, height, and weight in children during and after therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 2018, 124, 4248–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, W.L.; Le, A.; Zheng, D.J.; Mitchell, H.R.; Rotatori, J.; Li, F.; Fahey, J.T.; Ness, K.K.; Kadan-Lottick, N.S. Physical activity barriers, preferences, and beliefs in childhood cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 2177–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, A.E.; Kahali, B.; Berndt, S.I.; Justice, A.E.; Pers, T.H.; Day, F.R.; Powell, C.; Vedantam, S.; Buchkovich, M.L.; Yang, J.; et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015, 518, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coumbe, B.G.T.; Groarke, J.D. Cardiovascular Autonomic Dysfunction in Patients with Cancer. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2018, 20, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, F.W.; Roberts, C.K.; Laye, M.J. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr. Physiol. 2012, 2, 1143–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, H.W., 3rd; Craig, C.L.; Lambert, E.V.; Inoue, S.; Alkandari, J.R.; Leetongin, G.; Kahlmeier, S.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. The pandemic of physical inactivity: Global action for public health. Lancet 2012, 380, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.F.; Saltzman, E.; Must, A.; Parsons, S.K. Do Childhood Cancer Survivors Meet the Diet and Physical Activity Guidelines? A Review of Guidelines and Literature. Int. J. Child Health Nutr. 2012, 1, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jess, L.; Bäck, M.; Jarfelt, M. Adult childhood cancer survivors’ perceptions of factors that influence their ability to be physically active. Support Care Cancer 2023, 31, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.F.; Jones, L.W. Modulation of cardiovascular toxicity in Hodgkin lymphoma: Potential role and mechanisms of aerobic training. Future Cardiol. 2015, 11, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, S.; Schuler, G.; Adams, V. Cardiovascular effects of exercise training: Molecular mechanisms. Circulation 2010, 122, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrecht, R.; Gielen, S.; Linke, A.; Fiehn, E.; Yu, J.; Walther, C.; Schoene, N.; Schuler, G. Effects of exercise training on left ventricular function and peripheral resistance in patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized trial. JAMA 2000, 283, 3095–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannuzzi, P.; Temporelli, P.L.; Corrà, U.; Tavazzi, L.; ELVD-CHF Study Group. Antiremodeling effect of long-term exercise training in patients with stable chronic heart failure: Results of the Exercise in Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Chronic Heart Failure (ELVD-CHF) Trial. Circulation 2003, 108, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbab-Zadeh, A.; Dijk, E.; Prasad, A.; Fu, Q.; Torres, P.; Zhang, R.; Thomas, J.D.; Palmer, D.; Levine, B.D. Effect of aging and physical activity on left ventricular compliance. Circulation 2004, 110, 1799–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrecht, R.; Wolf, A.; Gielen, S.; Linke, A.; Hofer, J.; Erbs, S.; Schoene, N.; Schuler, G. Effect of exercise on coronary endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, N.; Vita, J.A.; Bader, D.S.; Sherman, D.L.; Hunter, L.M.; Holbrook, M.; O’Malley, C.; Keaney, J.F., Jr.; Balady, G.J. Effect of exercise on upper and lower extremity endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2002, 90, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambrecht, R.; Adams, V.; Erbs, S.; Linke, A.; Kränkel, N.; Shu, Y.; Baither, Y.; Gielen, S.; Thiele, H.; Gummert, J.F.; et al. Regular physical activity improves endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease by increasing phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 2003, 107, 3152–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, K.D.; Dinenno, F.A.; Tanaka, H.; Clevenger, C.M.; DeSouza, C.A.; Seals, D.R. Regular aerobic exercise modulates age-associated declines in cardiovagal baroreflex sensitivity in healthy men. J. Physiol. 2000, 529, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courneya, K.S.; Sellar, C.M.; Stevinson, C.; McNeely, M.L.; Peddle, C.J.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Tankel, K.; Basi, S.; Chua, N.; Mazurek, A.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of aerobic exercise on physical functioning and quality of life in lymphoma patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4605–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courneya, K.S.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Franco-Villalobos, C.; Crawford, J.J.; Chua, N.; Basi, S.; Norris, M.K.; Reiman, T. Effects of supervised exercise on progression-free survival in lymphoma patients: An exploratory follow-up of the HELP Trial. Cancer Causes Control. 2015, 26, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.; Steindorf, K.; Wiskemann, J.; Ulrich, C.M. Impact of resistance training in cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 2080–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurca, R.; Lamonte, M.J.; Barlow, C.E.; Kampert, J.B.; Church, T.S.; Blair, S.N. Association of muscular strength with incidence of metabolic syndrome in men. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, J.R.; Castro-Piñero, J.; Artero, E.G.; Ortega, F.B.; Sjöström, M.; Suni, J.; Castillo, M.J. Predictive validity of health-related fitness in youth: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardee, J.P.; Porter, R.R.; Sui, X.; Archer, E.; Lee, I.M.; Lavie, C.J.; Blair, S.N. The effect of resistance exercise on all-cause mortality in cancer survivors. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Asnaani, A.; Vonk, I.J.; Sawyer, A.T.; Fang, A. The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses. Cognit Ther. Res. 2012, 36, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Singh, S.; Sibinga, E.M.; Gould, N.F.; Rowland-Seymour, A.; Sharma, R.; Berger, Z.; Sleicher, D.; Maron, D.D.; Shihab, H.M.; et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, J.A.; Garland, S.N.; Heckler, C.E.; Perlis, M.L.; Peoples, A.R.; Shayne, M.; Savard, J.; Daniels, N.P.; Morrow, G.R. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy and armodafinil for insomnia after cancer treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, J.E.; Irwin, M.R. Mind-body therapies and control of inflammatory biology: A descriptive review. Brain Behav. Immun. 2016, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D. Dietary and Policy Priorities for Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes, and Obesity: A Comprehensive Review. Circulation 2016, 133, 187–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, D.J.; Lindroos, A.K.; Jebb, S.A.; Sjöström, L.; Carlsson, L.M.; Ambrosini, G.L. Dietary patterns, cardiometabolic risk factors, and the incidence of cardiovascular disease in severe obesity. Obesity 2015, 23, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirahatake, K.M.; Jiang, L.; Wong, N.D.; Shikany, J.M.; Eaton, C.B.; Allison, M.A.; Martin, L.; Garcia, L.; Zaslavsky, O.; Odegaard, A.O. Diet Quality and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Postmenopausal Women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Women’s Health Initiative. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e013249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendia, J.R.; Li, Y.; Hu, F.B.; Cabral, H.J.; Bradlee, M.L.; Quatromoni, P.A.; Singer, M.R.; Curhan, G.C.; Moore, L.L. Regular Yogurt Intake and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among Hypertensive Adults. Am. J. Hypertens. 2018, 31, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.L.; Crandell, J.L.; Bell, R.A.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Dabelea, D.; Liese, A.D. Change in DASH diet score and cardiovascular risk factors in youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Nutr. Diabetes 2013, 3, e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, P.J.; Segal, R.J.; Vallis, M.; Ligibel, J.A.; Pond, G.R.; Robidoux, A.; Blackburn, G.L.; Findlay, B.; Gralow, J.R.; Mukherjee, S.; et al. Randomized trial of a telephone-based weight loss intervention in postmenopausal women with breast cancer receiving letrozole: The LISA trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2231–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Tran, M.T.D.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodbard, H.W.; Dougherty, T.; Taddei-Allen, P. Efficacy of oral semaglutide: Overview of the PIONEER clinical trial program and implications for managed care. Am. J. Manag. Care 2020, 26, S335–S343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Aronne, L.J.; Ahmad, N.N.; Wharton, S.; Connery, L.; Alves, B.; Kiyosue, A.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Chao, A.M.; Machineni, S.; Kushner, R.; Ard, J.; Srivastava, G.; Halpern, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Tirzepatide after intensive lifestyle intervention in adults with overweight or obesity: The SURMOUNT-3 phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2909–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butragueño, J.; Ruiz, J.R. Metabolic alliance: Pharmacotherapy and exercise management of obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lown, E.A.; Hijiya, N.; Zhang, N.; Srivastava, D.K.; Leisenring, W.M.; Nathan, P.C.; Castellino, S.M.; Devine, K.A.; Dilley, K.; Krull, K.R.; et al. Patterns and predictors of clustered risky health behaviors among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 2016, 122, 2747–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author Country | Population | Age at Evaluation Time from Diagnosis/Treatment | Treatment Exposure | Outcomes of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | ||||

| Williams et al., 2022 [28] United States | N = 1760 47.9% male 91.8% white | 37 (21–54) 23.15 (14.7, 34.3) median years from diagnosis | RT: 79.1% Anthracycline: 43.4% Cyclophosphamide: 59% Methotrexate: 6.2% Bleomycin: 35.8% Corticosteroids: 58.1% |

|

| De Lima et al., 2018 [29] Brazil | N = 512 41.7% male 25.0% white | 32 ± 8 4.8 ± 3.54 mean years from diagnosis | NR |

|

| Jones et al., 2014 [30] United States | N = 1187 50.5% male 85.3% white | 42 (22–58) 16.7 (8.2–28.7) mean years from diagnosis | Any RT: 91.4% Chest RT: 85.7% Any chemo: 63% Alkylating agent: 59.8% Anthracycline: 20% |

|

| Oldervoll et al., 2007 [31] Norway | N = 476 56.0% male | 46 (21–73) 17 ± 7.5 median years follow-up | RT: 27% Chemo: 18% Combined: 53% |

|

| Fitness: cardiorespiratory | ||||

| Heemelaar et al., 2021 [32] The Netherlands | N = 75 41.3% male | 46 ± 12 17.6 (12.4–25.8) mean years from treatment | RT: 100% Chemo: 80% |

|

| Rizwan et al., 2021 [33] United States | N = 64 33.0% male 100.0% white | 51 (26–71) 23 (11–51) median years from treatment | Mantle RT: 25% Mantle and para-aortic RT: 55% Mini-mantle RT: 1.6% Mantle and cardiac RT: 6.3% Anthracyclines: 41% Surgery: 64% |

|

| Ng et al., 2005 [34] United States | N = 503 49.0% male | 44 (16–82) 15 median years follow-up | RT: 61% Chemo: 4% Combined: 35% |

|

| Adams et al., 2004 [35] United States | N = 48 48.0% male 94.7% white | 31.9 (18.7–49.5) 14.3 (5.9–27.5) median years from diagnosis | RT: 100% Chemo: 43.75% Anthracycline: 8.33% |

|

| Kadota et al., 1988 [36] United States | N = 12 58.3% male | NR 9.8 mean years from treatment | RT: 100% Chemo: 33.3% |

|

| Fitness: muscle strength | ||||

| Tacyildiz et al., 2024 [37] Turkey | N = 50 66.0% male | 21 ± 6 0–5 years from diagnosis: 25% 5–10 years from diagnosis: 26% >10 years from diagnosis: 49% | RT: 100% Chemo: 100% |

|

| Stadtbaeumer et al., 2020 [38] Germany | N = 3596 45.9% male | 35 ± 11 NR | NR |

|

| Wogksch et al., 2019 [39] United States | N = 336 53.6% male 85.1% white | NR 28.1 ± 9.2 mean years from treatment | Any RT: 97.6% Lung RT (>25 Gy): 64% Chest RT (>25 Gy): 86% Bleomycin: 25% Alkylating agent: 68.5% Doxorubicin: 64.3% Dexamethasone: 2.7% Prednisone: 55.7% Vinblastine: 67.3% Vincristine: 66.7% |

|

| Rach et al., 2016 [40] United States | N = 751 49.5% male | NR NR | Chest RT (≥30 Gy): 59.3% Anthracycline: 21% Alkylating agents: 55.8% Bleomycin: 19.6% Vinca alkaloids and heavy metals: 55.7% |

|

| Roper et al., 2013 [41] United States | N = 40 40.0% male 90.0% white | 31 ± 6 NR | RT: 5% Chemo: 59% Combined: 36% |

|

| Calaminus et al., 2014 [42] Germany | N = 725 45.9% male | NR 15.26 ± 5.89 mean years from diagnosis | RT (>30 Gy): 31.6% Chemo (>6 cycles): 28.7% |

|

| Van Leeuwen-Segarceanu et al., 2012 [43] The Netherlands | N = 81 50.0% male | 53 ± 10 NR | RT: 100% Chemo: 50% |

|

| Hjermstad et al., 2006 [44] Norway | N = 475 56.0% male 100.0% white | 46 ± 12 16.3 (4.4–36) median years median follow-up | RT: 31% Chemo: 14% Combined: 55% |

|

| Body composition | ||||

| Kaste et al., 2009 [45] United States | N = 109 50.5% male 85.3% white | NR 9.4 (5.1–13.0) median years from treatment | Lumbar spine RT: 29.3% Procarbazine: 60.2% Cyclophosphamide: 63.9% Methotrexate (>150 mg/m2): 30.8% Prednisone (>2000 mg/m2): 34.6% |

|

| Van Beek et al., 2009 [46] The Netherlands | N = 88 63.6% male | 27 (18–43) 15.5 (5.6–30.2) median years from treatment | RT: 19.8% Chemo: 100% |

|

| Autonomic dysfunction | ||||

| Groarke et al., 2015 [47] United States | N = 263 46.0% male | 50 ± 11 19 (12–26) mean years from treatment | RT: 100% Adjuvant anthracycline: 46% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marmol-Perez, A.; Berkman, A.M.; Ness, K.K. Associations Between Physical Activity, Fitness, Perceived Health, Chronic Disease and Mortality in Adult Survivors of Childhood and Young Adult Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Scoping Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 3625. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223625

Marmol-Perez A, Berkman AM, Ness KK. Associations Between Physical Activity, Fitness, Perceived Health, Chronic Disease and Mortality in Adult Survivors of Childhood and Young Adult Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Scoping Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(22):3625. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223625

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarmol-Perez, Andres, Amy M. Berkman, and Kirsten K. Ness. 2025. "Associations Between Physical Activity, Fitness, Perceived Health, Chronic Disease and Mortality in Adult Survivors of Childhood and Young Adult Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Scoping Review" Cancers 17, no. 22: 3625. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223625

APA StyleMarmol-Perez, A., Berkman, A. M., & Ness, K. K. (2025). Associations Between Physical Activity, Fitness, Perceived Health, Chronic Disease and Mortality in Adult Survivors of Childhood and Young Adult Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Scoping Review. Cancers, 17(22), 3625. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223625