Beyond the Warburg Effect: Modeling the Dynamic and Context-Dependent Nature of Tumor Metabolism

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model

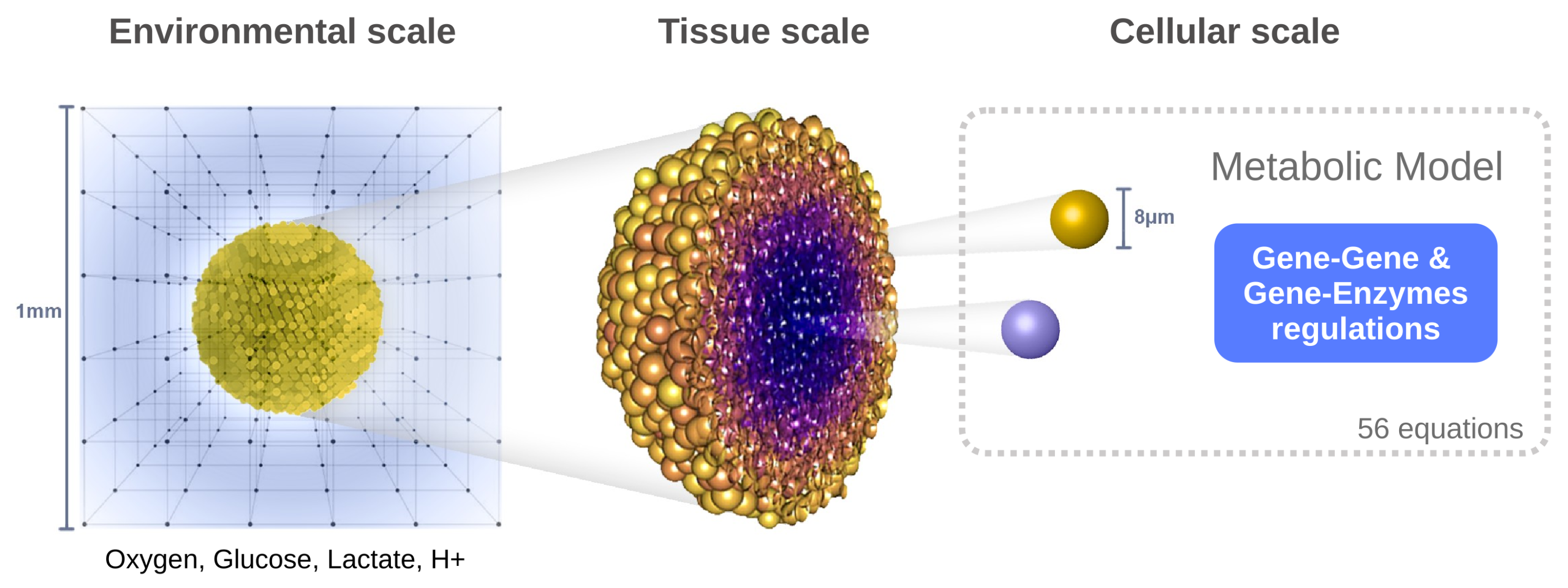

2.1. A Hybrid Multiscale Framework

2.1.1. Spatial Scales

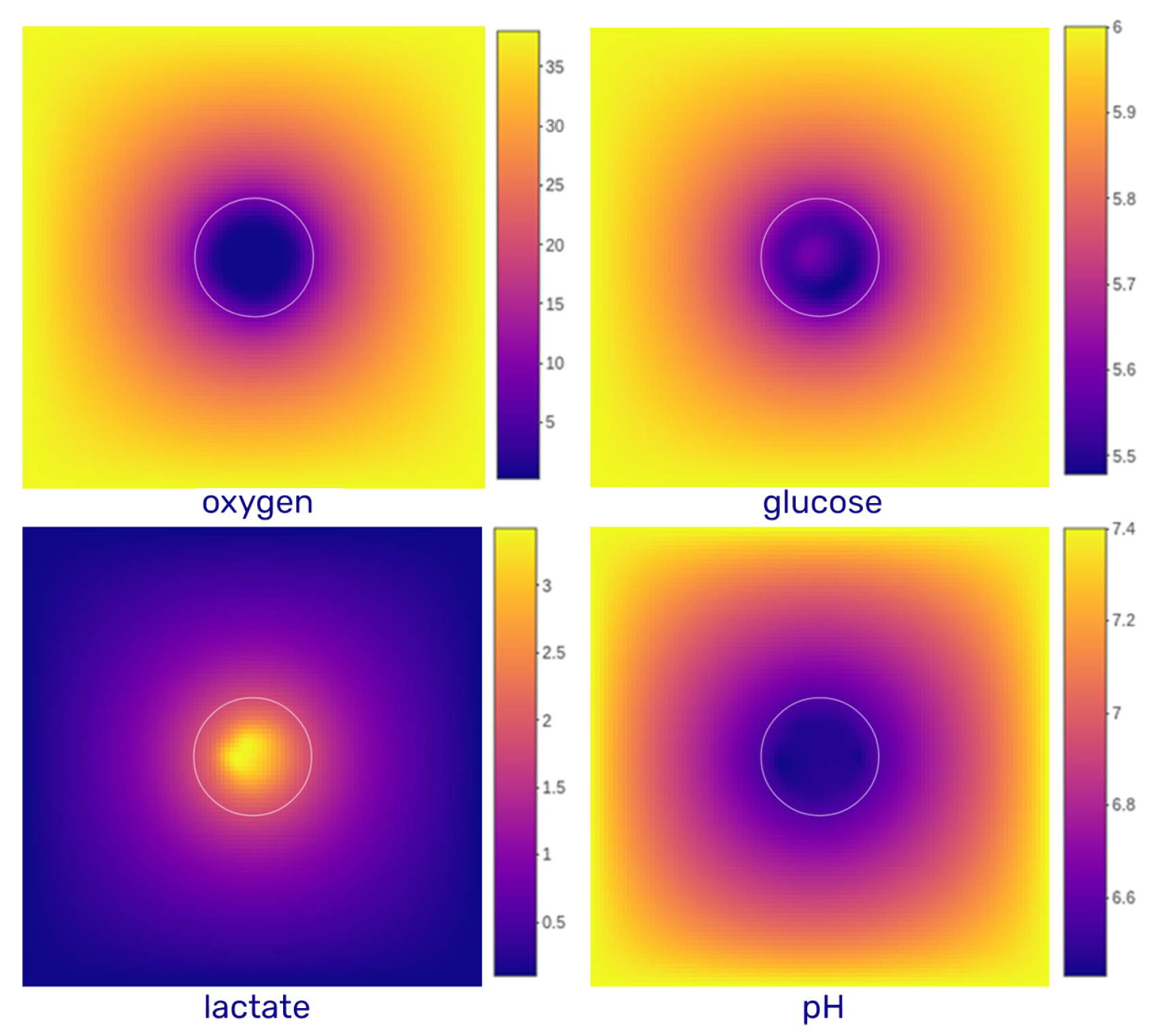

- Environmental scale: The extracellular medium is described using reaction–diffusion equations for four key species: oxygen, glucose, lactate, and protons (to evaluate pH). This level captures the spatiotemporal distribution of diffusible molecules.

- Tissue scale: The tumor is modeled as a population of discrete agents, each representing a single cell. The agent-based model governs cellular behaviors such as movement, division, death, and mechanical interactions (e.g., adhesion, repulsion).

- Cellular scale: Each cell possesses its own dynamic metabolic model based on reaction kinetics (primarily Michaelis–Menten equations), which is locally influenced by environmental conditions. These intracellular dynamics determine the cell’s phenotype and fate over time.

2.1.2. Temporal Scales

- Diffusion: 0.6 s

- Metabolism: 1.2 s (resolution of differential equations = diffusion)

- Mechanics (e.g., movement, interaction): 6 s ( diffusion)

- Phenotype evaluation: 6 min ( diffusion)

2.2. Extracellular Environment

- Oxygen: Extracellular oxygen varies significantly within tumor tissues. Peripheral cells consume oxygen rapidly, leading to depletion in the spheroid core. As oxygen diffuses passively into cells, intracellular concentrations are assumed to equilibrate with extracellular levels. Physiological values range from 160 mmHg in air to 70 mmHg in arteries and 38 mmHg in healthy tissues, and they drop below 15 mmHg under hypoxia, reaching pathological hypoxia below 8 mmHg [11]. In our simulations, initial oxygen concentrations range from 0 to 38 mmHg (converted to mM using the Valabrègue coefficient, [12]). Dirichlet boundary conditions are applied to mimic continuous oxygen exposure, as in spheroid cultures. The diffusion coefficient is [13].

- Glucose: Glucose is also consumed by cells and enters via facilitated diffusion through GLUT transporters. Its average blood concentration is approximately 5–6 mM. As the culture medium is regularly renewed in spheroid experiments, glucose concentration at the domain boundaries is held constant (Dirichlet condition). The diffusion coefficient used is [14].

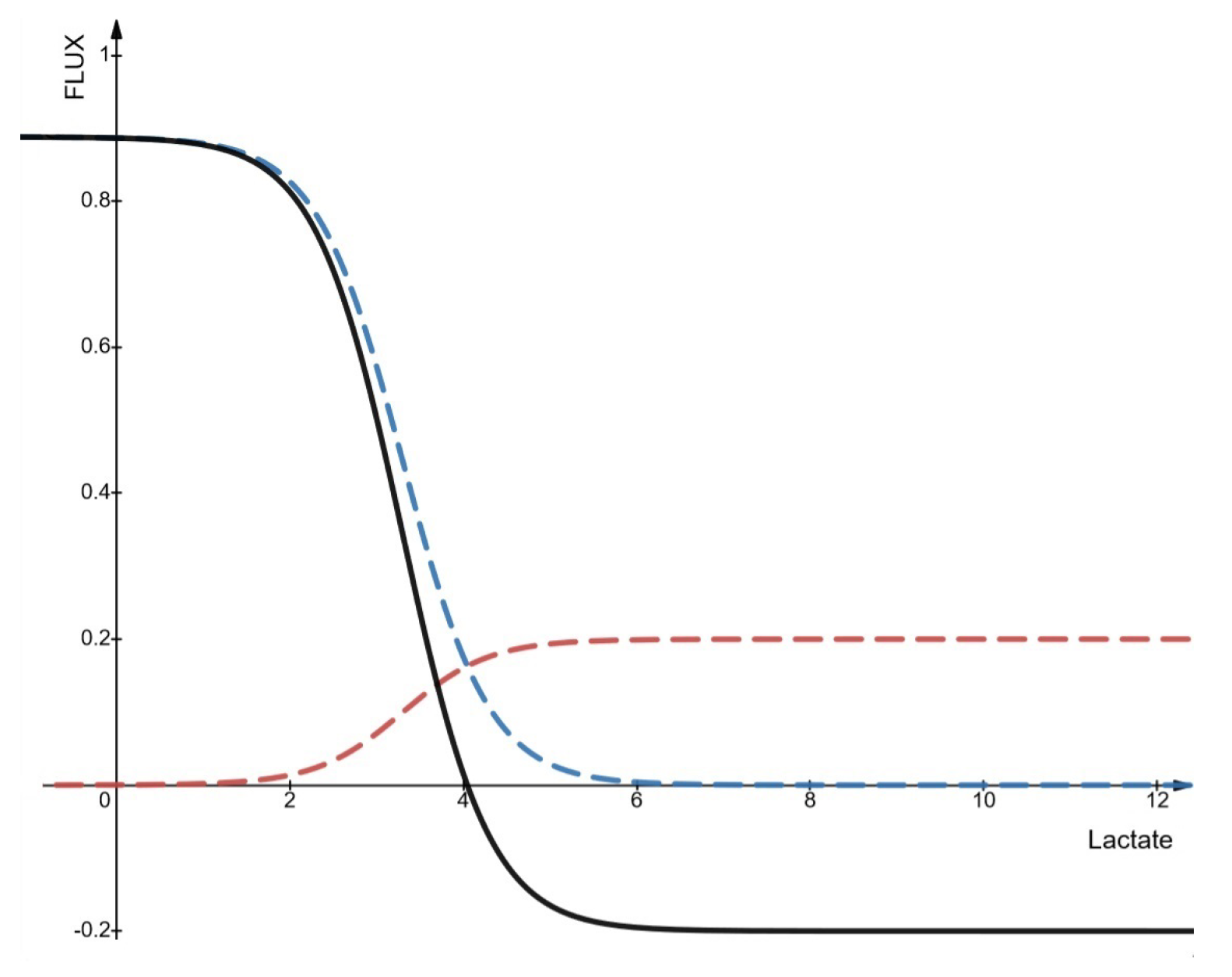

- Lactate: Lactate is primarily produced by cells and exchanged with the environment via monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) in the form of lactic acid, co-transported with protons. At the domain boundaries, lactate concentration is generally fixed at zero (Dirichlet condition), reflecting regular renewal of the medium. In specific simulations, zero-flux (Neumann) conditions are applied to allow lactate accumulation. The diffusion coefficient is [15].

- H+: Proton dynamics are coupled to lactate transport, entering and exiting the cell through MCTs. The resulting extracellular pH typically ranges from physiological (7.4) to acidic (4.0) values. A fixed boundary pH of 7.4 is imposed (Dirichlet condition), although in some simulations, zero-flux boundaries are used. The diffusion coefficient for protons is [16].

2.3. Cell Metabolism

- Temporal dynamics of individual cell states is tracked, to follow time-resolved trajectories.

- The extracellular environment is updated dynamically, and pH—which can reshape the metabolic landscape—is included.

- Spatial heterogeneity within a growing tumor mass is considered.

2.4. Cell Cycle and Cell Death

2.4.1. Cell Cycle

2.4.2. Cell Death

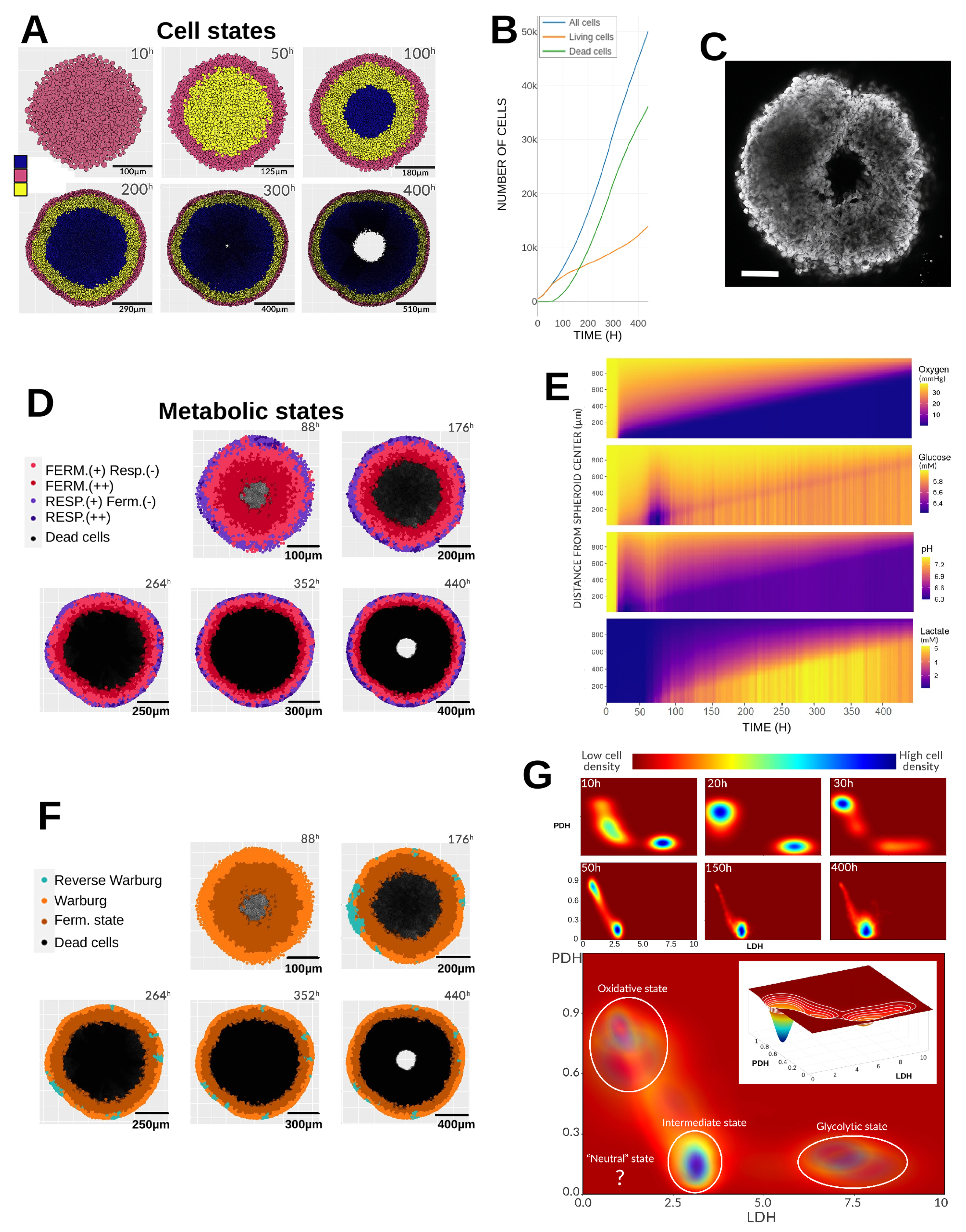

3. Results

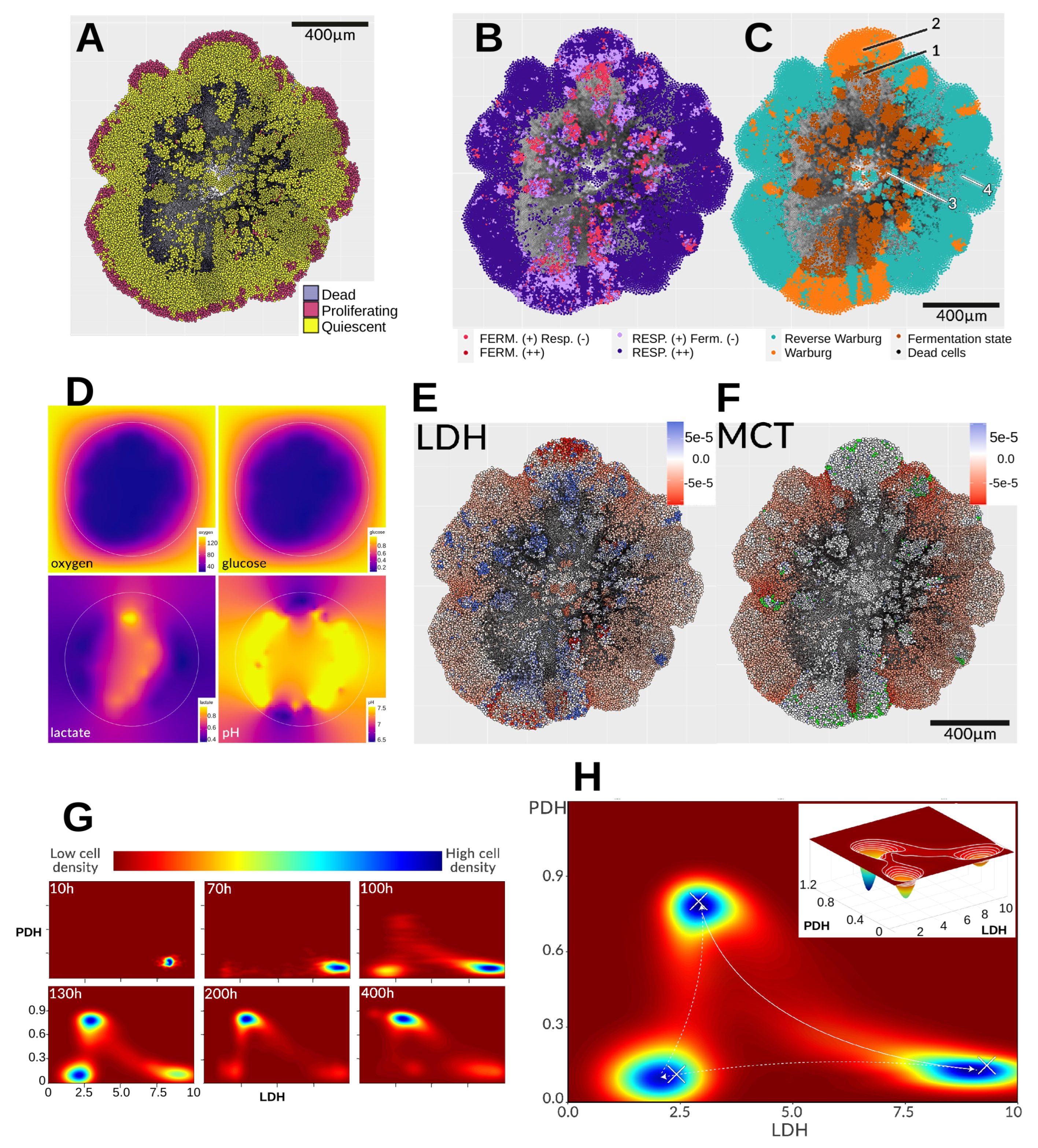

3.1. Reference Simulation

3.1.1. Initial Conditions

3.1.2. Gradients and Radial Profiles

3.1.3. Emerging Phenotypes

3.1.4. Metabolic Landscape

3.2. Environmental Perturbations

3.2.1. Cyclic Hypoxia

3.2.2. Acid Shock

3.2.3. Glucose Depletion

3.3. Challenging the Glycolytic Metabolism

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| HIF | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MCT | Monocarboxylate transporter |

| PDH | Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

Appendix A. Model Details

Appendix A.1. Non-Homogeneous Diffusion

Appendix A.2. Model of Cell Metabolism

| IDs | Enzymes | Reactions |

|---|---|---|

| r1 | GluT1 | Gluout ⇌ Gluin |

| r2 | HK | Gluin + ATP ⇌ G6P + ADP |

| r3 | GPI | G6P ⇌ F6P |

| r4 | PFK-1 | F6P + ATP ⇌ FBP + ADP |

| r5 | ALD | FBP ⇌ DHAP + G3P |

| r6 | TPI | DHAP ⇌ G3P |

| r7 | GAPDH | G3P + NAD+ ⇌ 1.3BPG + NADH |

| r8 | PGK | 1.3BPG + ADP ⇌ 3PG + ATP |

| r9 | PGAM | 3PG ⇌ 2PG |

| r10 | ENO | 2PG ⇌ PEP |

| r11 | PKM2 | PEP + ADP ⇌ Pyruvate + ATP |

| r12 | LDH | Pyruvate + NADH ⇌ Lactate + NAD+ |

| r13 | G6PD | 6PGD G6P ⇌ R5P |

| r14 | ATPases | ATP ⟶ ADP |

| r15 | AK | AMP + ATP ⇌2ADP |

| r16 | PFKFB2 | 3F6P ⇌ F2.6BP |

| r17 | PHGDH | 3PG ⟶ Serine |

| r18 | PDH | Pyruvate + ADP ⟶ Citrate + ATP + Complex2 |

| r19 | ACC | Complex2 + 3ATP + AC-CoA ⟶ mal-CoA + 3ADP + NAD+ |

| r20 | SOD | ROS ⟶ Null |

| r21 | Lactate + ⇌ Lactateextra + | |

| r22 | 3R5P ⇌ 2F6P + G3P | |

| r23 | Nucleotide Biosynthesis | R5P ⟶ Null |

| r24 | Serine Consumption | Serine ⟶ Null |

| r25 | GPDH | NADH + ADP ⟶ Complex2 + ATP + NAD+ |

| r26 | Citrate + 3ADP ⟶ 3ATP + 4Complex2 | |

| r27 | Complex2 + 1.5ADP ⟶ 1.5ATP | |

| r28 | Complex2 ⟶ ROS | |

| r29 | NOX | null ⟶ ROS |

| r30 | Citrate ⟶ Null |

- Fluxes entering and leaving the cell

- the intracellular lactate/pyruvate ratio exceeds ∼10 at all pH values;

- pyruvate concentration remains relatively constant above 0.1 mM;

- under acidic extracellular pH, when extracellular lactate exceeds intracellular levels or the lactate/pyruvate ratio decreases, lactate enters the cell;

- at neutral pH, lactate influx remains low even if extracellular lactate is higher.

- Implementation in PhysiCell

- Regulation of gene expression

References

- Jacquet, P.; Stéphanou, A. Metabolic Reprogramming, Questioning, and Implications for Cancer. Biology 2021, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, P.; Stéphanou, A. Searching for the metabolic signature of cancer: A review from Warburg’s time to now. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, C.; Maspero, D.; Di Filippo, M.; Colombo, R.; Pescini, D.; Graudenzi, A.; Westerhoff, H.V.; Alberghina, L.; Vanoni, M.; Mauri, G. Integration of single-cell RNA-seq data into population models to characterize cancer metabolism. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquet, P.; Stéphanou, A. A reduced model of cell metabolism to revisit the glycolysis-OXPHOS relationship in the deregulated tumor microenvironment. J. Theor. Biol. 2023, 562, 111434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, J. Uncovering the Underlying Mechanisms of Cancer Metabolism through the Landscapes and Probability Flux Quantifications. iScience 2020, 23, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wu, H.; Dai, C.; Pan, Q.; Ding, Z.; Hu, D.; Ji, B.; Luo, Y.; Hu, X. Beyond Warburg effect—Dual metabolic nature of cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ying, M.; Hu, X. Lactic acidosis switches cancer cells from aerobic glycolysis back to dominant oxidative phosphorylation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, M.; Piccinini, F.; Arienti, C.; Zamagni, A.; Santi, S.; Polico, R.; Bevilacqua, A.; Tesei, A. 3D tumor spheroid models for in vitro therapeutic screening: A systematic approach to enhance the biological relevance of data obtained. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, C.J. Sphéroïdes: Le modèle de référence pour la culture in vitro des tumeurs solides ? Bull. Cancer 2018, 105, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarizadeh, A.; Heiland, R.; Friedman, S.H.; Mumenthaler, S.M.; Macklin, P. PhysiCell: An open source physics-based cell simulator for 3-D multicellular systems. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, S.R. Defining normoxia, physoxia and hypoxia in tumours—Implications for treatment response. Br. J. Radiol. 2014, 87, 20130676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valabrègue, R.; Aubert, A.; Burger, J.; Bittoun, J.; Costalat, R. Relation between Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism Explained by a Model of Oxygen Exchange. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003, 23, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, J.; Ulldemolins, A.; Farré, R.; Almendros, I. Oxygen Biosensors and Control in 3D Physiomimetic Experimental Models. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, W.D.; Litman, T. Channels, Carriers, and Pumps: An Introduction to Membrane Transport; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pérez, A.I.; López-Beltrán, E.A.; Klüner, P.; Luque, J.; Ballesteros, P.; Cerdán, S. Molecular Crowding and Viscosity as Determinants of Translational Diffusion of Metabolites in Subcellular Organelles. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 362, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussler, E.L. Diffusion: Mass Transfer in Fluid Systems; CAMBRIDGE: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Hernández, A.; Gallardo-Pérez, J.C.; Rodríguez-Enríquez, S.; Encalada, R.; Moreno-Sánchez, R.; Saavedra, E. Modeling cancer glycolysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2011, 1807, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T.A.; Tsuda, A.; Uesaka, M.; Fujimori, A.; Kamada, T.; Tsujii, H.; Okayasu, R. In vitro characterization of cells derived from chordoma cell line U-CH1 following treatment with X-rays, heavy ions and chemotherapeutic drugs. Radiat. Oncol. 2011, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leist, M.; Single, B.; Castoldi, A.F.; Kühnle, S.; Nicotera, P. Intracellular Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Concentration: A Switch in the Decision Between Apoptosis and Necrosis. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampaloni, F.; Reynaud, E.G.; Stelzer, E.H.K. The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlides, S.; Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Castello-Cros, R.; Flomenberg, N.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; Frank, P.G.; Casimiro, M.C.; Wang, C.; Fortina, P.; Addya, S.; et al. The reverse Warburg effect: Aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 3984–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewhirst, M.W. Relationships between Cycling Hypoxia, HIF-1, Angiogenesis and Oxidative Stress. Radiat. Res. 2009, 172, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, S.B.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Hammond, E.M. Cyclic Hypoxia: An Update on Its Characteristics, Methods to Measure It and Biological Implications in Cancer. Cancers 2020, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navale, A.M.; Paranjape, A.N. Glucose transporters: Physiological and pathological roles. Biophys. Rev. 2016, 8, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickaert, A.; Saiselet, M.; Dom, G.; De Deken, X.; Dumont, J.E.; Feron, O.; Sonveaux, P.; Maenhaut, C. Cancer heterogeneity is not compatible with one unique cancer cell metabolic map. Oncogene 2017, 36, 2637–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, I.G.; García-Aznar, J.M. Hybrid computational models of multicellular tumour growth considering glucose metabolism. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanoni, M.; Palumbo, P.; Busti, S.; Alberghina, L. A critical review of multiscale modeling for predictive understanding of cancer cell metabolism. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2024, 39, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Deng, M.; Wang, Z.; Huang, C. MMP3C: An in-silico framework to depict cancer metabolic plasticity using gene expression profiles. Briefings Bioinform. 2023, 25, bbad471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Lu, M.; Jung, K.H.; Park, J.H.; Yu, L.; Onuchic, J.N.; Kaipparettu, B.A.; Levine, H. Elucidating cancer metabolic plasticity by coupling gene regulation with metabolic pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3909–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Wang, C.; Fessler, J.; DeTomaso, D.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Kaminski, J.; Zaghouani, S.; Christian, E.; Thakore, P.; Schellhaass, B.; et al. Metabolic modeling of single Th17 cells reveals regulators of autoimmunity. Cell 2021, 184, 4168–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walenta, S.; Doetsch, J.; Mueller-Klieser, W.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A. Metabolic Imaging in Multicellular Spheroids of Oncogene-transfected Fibroblasts. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2000, 48, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.S.; Barros, A.S.; Costa, E.C.; Moreira, A.F.; Correia, I.J. 3D tumor spheroids as in vitro models to mimic in vivo human solid tumors resistance to therapeutic drugs. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 116, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz-López, K.G.; Castro-Muñoz, L.J.; Reyes-Hernández, D.O.; García-Carrancá, A.; Manzo-Merino, J. Lactate in the Regulation of Tumor Microenvironment and Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, M.Á. Metabolic Reprogramming is a Hallmark of Metabolism Itself. BioEssays 2020, 42, 2000058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.; Fischer, S.C.; Mattheyer, C.; Pampaloni, F.; Stelzer, E.H.K. Multiscale image analysis reveals structural heterogeneity of the cell microenvironment in homotypic spheroids. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segel, I.H. Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady State Enzyme Systems; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ahnert, K.; Mulansky, M.; Simos, T.E.; Psihoyios, G.; Tsitouras, C.; Anastassi, Z. Odeint—Solving Ordinary Differential Equations in C++. arXiv 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.E.; Felmlee, M.A. Overview of the Proton-coupled MCT (SLC16A) Family of Transporters: Characterization, Function and Role in the Transport of the Drug of Abuse γ-Hydroxybutyric Acid. AAPS J. 2008, 10, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafech, A.; Jacquet, P.; Beaujean, C.; Fertin, A.; Usson, Y.; Stéphanou, A. Characterization of the Intracellular Acidity Regulation of Brain Tumor Cells and Consequences for Therapeutic Optimization of Temozolomide. Biology 2023, 12, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbansky, E.T.; Schock, M.R. Understanding, Deriving, and Computing Buffer Capacity. J. Chem. Educ. 2000, 77, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Oxygen | Glucose | Lactate | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| + | + | ++ | Lactate import |

| + | + | + | Lactate excretion |

| + | + | − | Low lactate excretion |

| + | − | + | Lactate import |

| + | − | − | Death |

| − | + | + | Lactate excretion |

| − | − | + | Death |

| − | − | − | Death |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jacquet, P.; Stéphanou, A. Beyond the Warburg Effect: Modeling the Dynamic and Context-Dependent Nature of Tumor Metabolism. Cancers 2025, 17, 3563. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213563

Jacquet P, Stéphanou A. Beyond the Warburg Effect: Modeling the Dynamic and Context-Dependent Nature of Tumor Metabolism. Cancers. 2025; 17(21):3563. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213563

Chicago/Turabian StyleJacquet, Pierre, and Angélique Stéphanou. 2025. "Beyond the Warburg Effect: Modeling the Dynamic and Context-Dependent Nature of Tumor Metabolism" Cancers 17, no. 21: 3563. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213563

APA StyleJacquet, P., & Stéphanou, A. (2025). Beyond the Warburg Effect: Modeling the Dynamic and Context-Dependent Nature of Tumor Metabolism. Cancers, 17(21), 3563. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213563