Integrative Multi-Omics Analyses Reveal Mechanisms of Resistance to Hsp90β-Selective Inhibition

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Line Selection and Classification

2.2. Cell Culture and Cell Viability Assays

2.3. Gene Expression and Proteomic Analysis

2.4. Metabolomics Analysis

2.5. LC–MS Analysis of Intracellular Kynurenine in Sensitive and NDNB-25 Acquired Resistant Lines

2.6. Gene Dependency and Functional Enrichment Analysis

2.7. Drug Sensitivity Analysis

2.8. Integrated Network and Pathway Analysis

2.9. NDNB-25 Resistance Modeling and Combination Drug Testing

2.10. Western Blot Analysis

3. Results

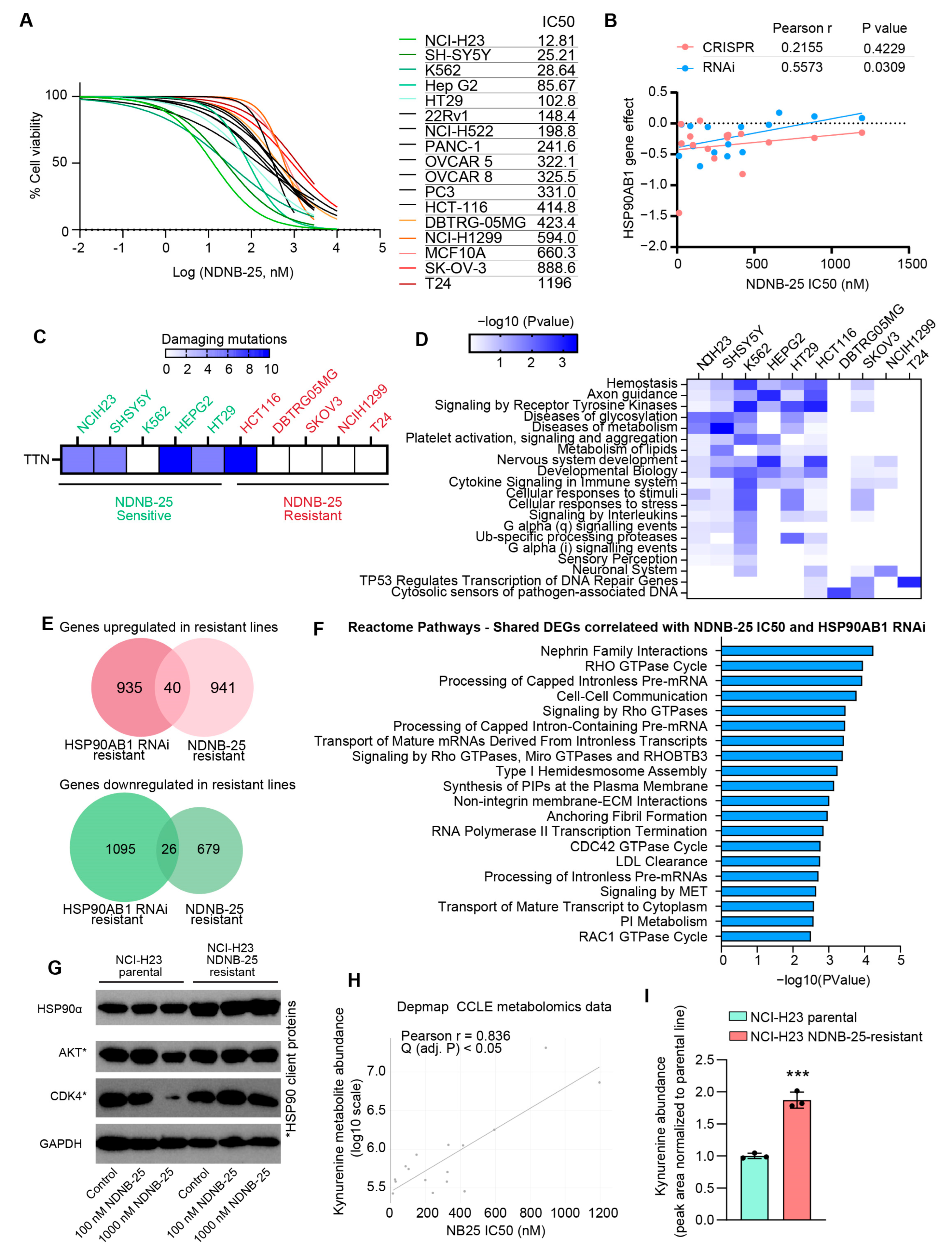

3.1. Identification and Characterization of HSP90AB1-Dependent and -Resistant Cancer Cell Lines

3.2. Gene Expression and Metabolite Profiling Reveal Distinct Metabolic and Signaling Programs in HSP90AB1-Dependent and -Resistant Cells

3.3. Integrated Gene Dependency and Drug Sensitivity Profiling Identifies Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in HSP90AB1-Resistant Cells

3.4. Shared and Unique Characteristics of Cell Lines Resistant to Hsp90β-Specific Inhibitor NDNB-25

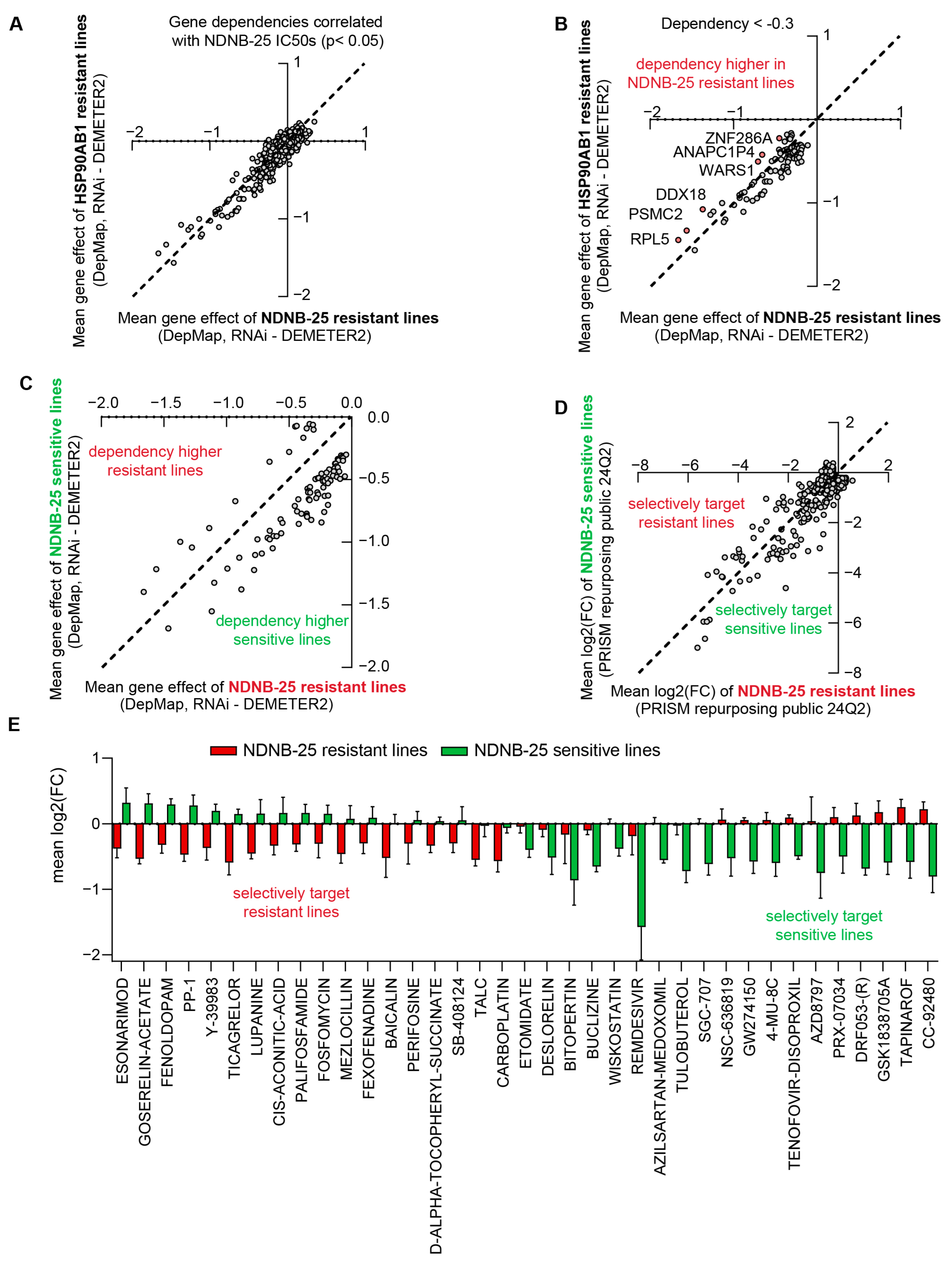

3.5. Comparative Analysis of HSP90AB1 Gene Dependency and NDNB-25 Sensitivity Reveals Unique Co-Dependencies and Drug Sensitivities

3.6. Integrated Gene–Drug Network Analysis Informs Rational Combination Screening to Validate Mechanisms of NDNB-25 Resistance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, B.; Piel, W.H.; Gui, L.; Bruford, E.; Monteiro, A. The HSP90 family of genes in the human genome: Insights into their divergence and evolution. Genomics 2005, 86, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, G.; Khandelwal, A.; Blagg, B.S. Anticancer inhibitors of Hsp90 function: Beyond the usual suspects. Adv. Cancer Res. 2016, 129, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Subbarao Sreedhar, A.; Kalmár, É.; Csermely, P.; Shen, Y.-F. Hsp90 isoforms: Functions, expression and clinical importance. FEBS Lett. 2004, 562, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taipale, M.; Jarosz, D.F.; Lindquist, S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: Emerging mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csermely, P.; Schnaider, T.; So, C.; Prohászka, Z.; Nardai, G. The 90-kDa molecular chaperone family: Structure, function, and clinical applications. A comprehensive review. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 79, 129–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, W. The role of heat shock protein in regulating the function, folding, and trafficking of the glucocorticoid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. (Print) 1993, 268, 21455–21458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felts, S.J.; Owen, B.A.; Nguyen, P.; Trepel, J.; Donner, D.B.; Toft, D.O. The hsp90-related protein TRAP1 is a mitochondrial protein with distinct functional properties. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 3305–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, A.K.; Thomas, T.; Gruss, P. Mice lacking HSP90beta fail to develop a placental labyrinth. Development 2000, 127, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuehlke, A.D.; Beebe, K.; Neckers, L.; Prince, T. Regulation and function of the human HSP90AA1 gene. Gene 2015, 570, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepel, J.; Mollapour, M.; Giaccone, G.; Neckers, L. Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitesell, L.; Lindquist, S.L. HSP90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Burns, T.F. Targeting Heat Shock Proteins in Cancer: A Promising Therapeutic Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, S.; Narasimharao Meka, P.; Banerjee, M.; Kent, C.N.; Blagg, B.S. Structure---based design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of hsp90β---selective inhibitors. Chem.–A Eur. J. 2021, 27, 14747–14764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, A.; Kent, C.N.; Balch, M.; Peng, S.; Mishra, S.J.; Deng, J.; Day, V.W.; Liu, W.; Subramanian, C.; Cohen, M. Structure-guided design of an Hsp90β N-terminal isoform-selective inhibitor. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.J.; Liu, W.; Beebe, K.; Banerjee, M.; Kent, C.N.; Munthali, V.; Koren III, J.; Taylor III, J.A.; Neckers, L.M.; Holzbeierlein, J. The development of Hsp90β-selective inhibitors to overcome detriments associated with pan-Hsp90 inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.S.; Banerji, U.; Tavana, B.; George, G.C.; Aaron, J.; Kurzrock, R. Targeting the molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90 (HSP90): Lessons learned and future directions. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013, 39, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhaveri, K.; Taldone, T.; Modi, S.; Chiosis, G. Advances in the clinical development of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) inhibitors in cancers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.B.; Eskew, J.D.; Vielhauer, G.A.; Blagg, B.S. The hERG channel is dependent upon the Hsp90α isoform for maturation and trafficking. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 1841–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serwetnyk, M.A.; Strunden, T.; Mersich, I.; Barlow, D.; D’Amico, T.; Mishra, S.J.; Houseknecht, K.L.; Streicher, J.M.; Blagg, B.S. Optimization of an Hsp90β-selective Inhibitor via Exploration of the Hsp90 N-terminal ATP-binding Pocket. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 297, 117925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwetnyk, M.A.; Crowley, V.M.; Brackett, C.M.; Carter, T.R.; Elahi, A.; Kommalapati, V.K.; Chadli, A.; Blagg, B.S. Enniatin A analogues as novel Hsp90 inhibitors that modulate triple-negative breast cancer. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisa, N.H.; Crowley, V.M.; Elahi, A.; Kommalapati, V.K.; Serwetnyk, M.A.; Llbiyi, T.; Lu, S.; Kainth, K.; Jilani, Y.; Marasco, D. Enniatin A inhibits the chaperone Hsp90 and unleashes the immune system against triple-negative breast cancer. Iscience 2023, 26, 108308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandi, M.; Huang, F.W.; Jané-Valbuena, J.; Kryukov, G.V.; Lo, C.C.; McDonald III, E.R.; Barretina, J.; Gelfand, E.T.; Bielski, C.M.; Li, H. Next-generation characterization of the cancer cell line encyclopedia. Nature 2019, 569, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsherniak, A.; Vazquez, F.; Montgomery, P.G.; Weir, B.A.; Kryukov, G.; Cowley, G.S.; Gill, S.; Harrington, W.F.; Pantel, S.; Krill-Burger, J.M.; et al. Defining a Cancer Dependency Map. Cell 2017, 170, 564–576.e516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ning, S.; Ghandi, M.; Kryukov, G.V.; Gopal, S.; Deik, A.; Souza, A.; Pierce, K.; Keskula, P.; Hernandez, D. The landscape of cancer cell line metabolism. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Chong, J.; Zhou, G.; de Lima Morais, D.A.; Chang, L.; Barrette, M.; Gauthier, C.; Jacques, P.-É.; Li, S.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: Narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W388–W396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger-Haber, M.; Stancliffe, E.; Arends, V.; Thyagarajan, B.; Sindelar, M.; Patti, G.J. A workflow to perform targeted metabolomics at the untargeted scale on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2021, 1, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Bailey, A.; Kuleshov, M.V.; Clarke, D.J.; Evangelista, J.E.; Jenkins, S.L.; Lachmann, A.; Wojciechowicz, M.L.; Kropiwnicki, E.; Jagodnik, K.M. Gene set knowledge discovery with Enrichr. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, M.; Stevenson, J.; Stahl, K.; Basu, R.; Coffman, A.; Kiwala, S.; McMichael, J.F.; Kuzma, K.; Morrissey, D.; Cotto, K.; et al. DGIdb 5.0: Rebuilding the drug–gene interaction database for precision medicine and drug discovery platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D1227–D1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropiwnicki, E.; Evangelista, J.E.; Stein, D.J.; Clarke, D.J.; Lachmann, A.; Kuleshov, M.V.; Jeon, M.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Ma’ayan, A. Drugmonizome and Drugmonizome-ML: Integration and abstraction of small molecule attributes for drug enrichment analysis and machine learning. Database 2021, 2021, baab017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Comjean, A.; Attrill, H.; Antonazzo, G.; Thurmond, J.; Chen, W.; Li, F.; Chao, T.; Mohr, S.E.; Brown, N.H. PANGEA: A new gene set enrichment tool for Drosophila and common research organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W419–W426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianevski, A.; Giri, A.K.; Aittokallio, T. SynergyFinder 3.0: An interactive analysis and consensus interpretation of multi-drug synergies across multiple samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W739–W743. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría, P.C.; Bernthaler, A.; Dupuis, P.; Mayer, B.; Picard, D. An interaction network predicted from public data as a discovery tool: Application to the Hsp90 molecular chaperone machine. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, J.M.; Pacini, C.; Pantel, S.; Behan, F.M.; Green, T.; Krill-Burger, J.; Beaver, C.M.; Younger, S.T.; Zhivich, V.; Najgebauer, H.; et al. Agreement between two large pan-cancer CRISPR-Cas9 gene dependency data sets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Young, M.J.; Li, R.; Jain, S.; Wernitznig, A.; Krill-Burger, J.M.; Lemke, C.T.; Monducci, D.; Rodriguez, D.J.; Chang, L.; et al. Paralog knockout profiling identifies DUSP4 and DUSP6 as a digenic dependence in MAPK pathway-driven cancers. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, C.; Dempster, J.M.; Boyle, I.; Gonçalves, E.; Najgebauer, H.; Karakoc, E.; van der Meer, D.; Barthorpe, A.; Lightfoot, H.; Jaaks, P.; et al. Integrated cross-study datasets of genetic dependencies in cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, S.; Winter, P.S.; Navia, A.W.; Williams, H.L.; DenAdel, A.; Lowder, K.E.; Galvez-Reyes, J.; Kalekar, R.L.; Mulugeta, N.; Kapner, K.S.; et al. Microenvironment drives cell state, plasticity, and drug response in pancreatic cancer. Cell 2021, 184, 6119–6137.e6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondeson, D.P.; Paolella, B.R.; Asfaw, A.; Rothberg, M.V.; Skipper, T.A.; Langan, C.; Mesa, G.; Gonzalez, A.; Surface, L.E.; Ito, K.; et al. Phosphate dysregulation via the XPR1–KIDINS220 protein complex is a therapeutic vulnerability in ovarian cancer. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulick, K.; Ahn, J.H.; Zong, H.; Rodina, A.; Cerchietti, L.; Gomes DaGama, E.M.; Caldas-Lopes, E.; Beebe, K.; Perna, F.; Hatzi, K.; et al. Affinity-based proteomics reveal cancer-specific networks coordinated by Hsp90. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corre, S.; Tardif, N.; Mouchet, N.; Leclair, H.M.; Boussemart, L.; Gautron, A.; Bachelot, L.; Perrot, A.; Soshilov, A.; Rogiers, A. Sustained activation of the Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor transcription factor promotes resistance to BRAF-inhibitors in melanoma. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheus, L.H.G.; Dalmazzo, S.V.; Brito, R.B.O.; Pereira, L.A.; de Almeida, R.J.; Camacho, C.P.; Dellê, H. 1-Methyl-D-tryptophan activates aryl hydrocarbon receptor, a pathway associated with bladder cancer progression. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, C.A.; Somarribas Patterson, L.F.; Mohapatra, S.R.; Dewi, D.L.; Sadik, A.; Platten, M.; Trump, S. The therapeutic potential of targeting tryptophan catabolism in cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Xu, Y.; Jing, P.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, J.; Dong, C.; Yao, L. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor leads to resistance to EGFR TKIs in non–small cell lung cancer by activating src-mediated bypass signaling. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Yang, P.-J.; Chiu, C.-C.; Liang, S.-S.; Ou-Yang, F.; Kan, J.-Y.; Hou, M.-F.; Wang, T.-N.; Tsai, E.-M. DEHP mediates drug resistance by directly targeting AhR in human breast cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 145, 112400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endler, A.; Chen, L.; Shibasaki, F. Coactivator recruitment of AhR/ARNT1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 11100–11110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, I.; Hosaka, M.; Haga, A.; Tsuji, N.; Nagata, Y.; Okada, H.; Fukuda, K.; Kakizaki, Y.; Okamoto, T.; Grave, E. The regulation mechanisms of AhR by molecular chaperone complex. J. Biochem. 2018, 163, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Hang, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, G. Cryo-EM structure of the cytosolic AhR complex. Structure 2023, 31, 295–308.e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K.; Bachman, J.A.; Muhlich, J.L.; Mitchison, T.J. shinyDepMap, a tool to identify targetable cancer genes and their functional connections from Cancer Dependency Map data. Elife 2021, 10, e57116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Sasse, R.; Budach, S.; Hnisz, D.; Marsico, A. Integration of multiomics data with graph convolutional networks to identify new cancer genes and their associated molecular mechanisms. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, M.; Dienstbier, N.; Schliehe-Diecks, J.; Scharov, K.; Tu, J.-W.; Gebing, P.; Hogenkamp, J.; Bilen, B.-S.; Furlan, S.; Picard, D.; et al. Co-targeting HSP90 alpha and CDK7 overcomes resistance against HSP90 inhibitors in BCR-ABL1+ leukemia cells. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmy, S.; Mishra, S.J.; Murphy, S.; Blagg, B.S.; Lu, X. Hsp90β inhibition upregulates interferon response and enhances immune checkpoint blockade therapy in murine tumors. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1005045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mersich, I.; Anik, E.; Ali, A.; Blagg, B.S.J. Integrative Multi-Omics Analyses Reveal Mechanisms of Resistance to Hsp90β-Selective Inhibition. Cancers 2025, 17, 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213488

Mersich I, Anik E, Ali A, Blagg BSJ. Integrative Multi-Omics Analyses Reveal Mechanisms of Resistance to Hsp90β-Selective Inhibition. Cancers. 2025; 17(21):3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213488

Chicago/Turabian StyleMersich, Ian, Eahsanul Anik, Aktar Ali, and Brian S. J. Blagg. 2025. "Integrative Multi-Omics Analyses Reveal Mechanisms of Resistance to Hsp90β-Selective Inhibition" Cancers 17, no. 21: 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213488

APA StyleMersich, I., Anik, E., Ali, A., & Blagg, B. S. J. (2025). Integrative Multi-Omics Analyses Reveal Mechanisms of Resistance to Hsp90β-Selective Inhibition. Cancers, 17(21), 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213488