Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with a History of Cancer: Safety of Immunomodulators in a Multicenter Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Immunomodulatory Treatments Before Index Cancer

3.3. Index Cancer: Characterization

3.4. Index Cancer: Treatment

3.5. Immunomodulatory Treatments After Index Cancer

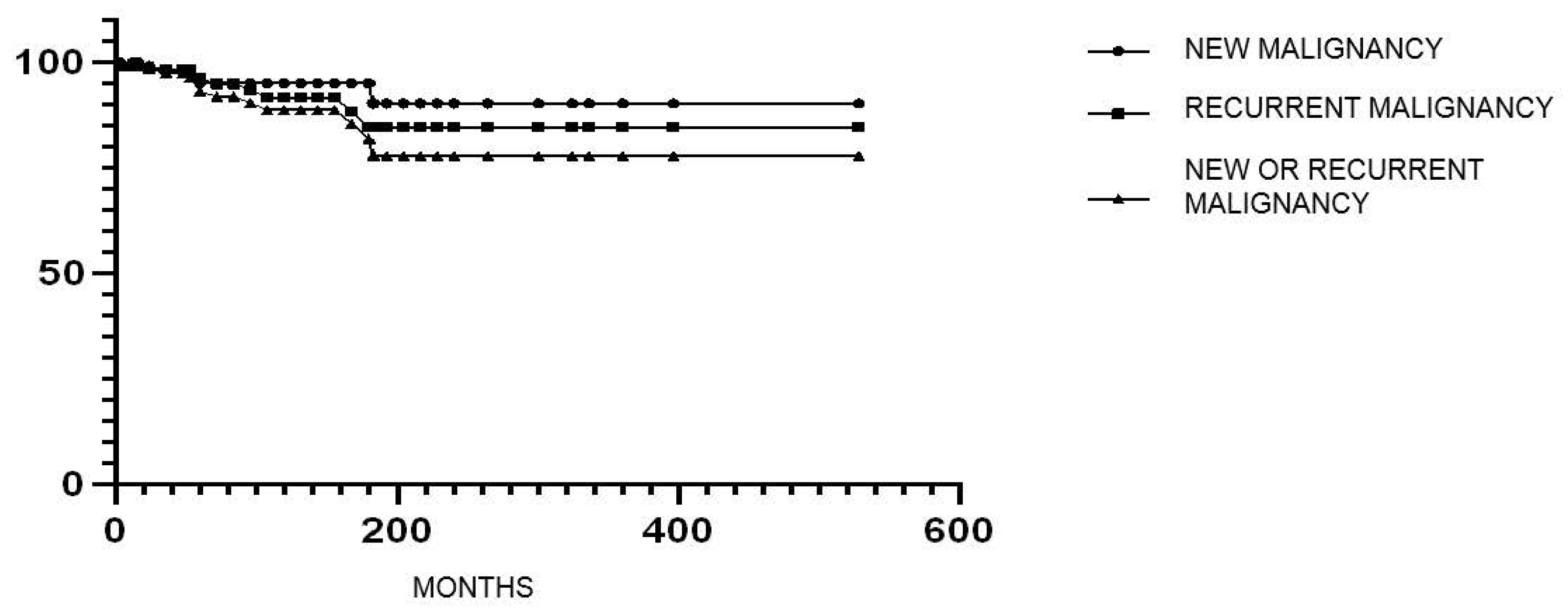

3.6. New or Recurrent Cancer in Patients Treated with Immunomodulators After Cancer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dolinger, M.; Torres, J.; Vermeire, S. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2024, 403, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Berre, C.; Honap, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2023, 402, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, J.M.; Zoega, H.; Shah, S.A.; Bright, R.M.; Mallette, M.; Moniz, H.; Grabert, S.A.; Bancroft, B.; Merrick, M.; Flowers, N.T.; et al. Incidence of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Rhode Island: Report from the Ocean State Crohn’s and Colitis Area Registry. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1456–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D’Amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; et al. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, D.P.; Truelove, S.C. Azathioprine in ulcerative colitis: Final report on controlled therapeutic trial. Br. Med. J. 1974, 4, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.; Minozzi, S.; Kopylov, U.; Verstockt, B.; Chaparro, M.; Buskens, C.; Warusavitarne, J.; Agrawal, M.; Allocca, M.; Atreya, R.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment. J. Crohns Colitis 2024, 18, 1531–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, T.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaugerie, L.; Brousse, N.; Bouvier, A.M.; Colombel, J.F.; Lémann, M.; Cosnes, J.; Hébuterne, X.; Cortot, A.; Bouhnik, Y.; Gendre, J.P.; et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective observational cohort study. Lancet 2009, 374, 1617–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Khosrotehrani, K.; Carrat, F.; Bouvier, A.M.; Chevaux, J.B.; Simon, T.; Carbonnel, F.; Colombel, J.F.; Dupas, J.L.; Godeberge, P.; et al. Increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients who receive thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmadani, M.; Mokaya, P.O.; Omer, A.A.A.; Kiptulon, E.K.; Klara, S.; Orsolya, M. Cancer burden in Europe: A systematic analysis of the GLOBOCAN database (2022). BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaugerie, L.; Itzkowitz, S.H. Cancers complicating inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.D.; Martin, C.F.; Pipkin, C.A.; Herfarth, H.H.; Sandler, R.S.; Kappelman, M.D. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Nugent, Z.; Demers, A.A.; Bernstein, C.N. Increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers among individuals with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Nagpal, S.J.; Murad, M.H.; Yadav, S.; Kane, S.V.; Pardi, D.S.; Talwalkar, J.A.; Loftus, E.V., Jr. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased risk of melanoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappelman, M.D.; Farkas, D.K.; Long, M.D.; Erichsen, R.; Sandler, R.S.; Sørensen, H.T.; Baron, J.A. Risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: A nationwide population-based cohort study with 30 years of follow-up evaluation. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C.; Itzkowitz, S.H. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, M.; Kirchgesner, J.; Rudnichi, A.; Carrat, F.; Zureik, M.; Carbonnel, F.; Dray-Spira, R. Association between Use of Thiopurines or Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists Alone or in Combination and Risk of Lymphoma in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. JAMA 2017, 318, 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrad, J.; Bernheim, O.; Colombel, J.F.; Malerba, S.; Ananthakrishnan, A.; Yajnik, V.; Hoffman, G.; Agrawal, M.; Lukin, D.; Desai, A.; et al. Risk of New or Recurrent Cancer in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Previous Cancer Exposed to Immunosuppressive and Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Agents. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, E.; Laharie, D.; Scott, F.I.; Mamtani, R.; Lewis, J.D.; Colombel, J.F.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Cancer Recurrence Following Immune-Suppressive Therapies in Patients with Immune-Mediated Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaugerie, L.; Carrat, F.; Colombel, J.F.; Bouvier, A.M.; Sokol, H.; Babouri, A.; Carbonnel, F.; Laharie, D.; Faucheron, J.L.; Simon, T.; et al. Risk of new or recurrent cancer under immunosuppressive therapy in patients with IBD and previous cancer. Gut 2014, 63, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R.E.; Freedman, M.; Ron, E.; Ries, L.A.G.; Hacker, D.G.; Edwards, B.K.; Tucker, M.A.; Fraumeni, J.F., Jr. New Malignancies Among Cancer Survivors: SEER Cancer Registries, 1993–2000; NIH Publication No. 05-5302; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Maaser, C.; Sturm, A.; Vavricka, S.R.; Kucharzik, T.; Fiorino, G.; Annese, V.; Calabrese, E.; Baumgart, D.C.; Bettenworth, D.; Borralho Nunes, P.; et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J. Crohns Colitis 2019, 13, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, I. The effect of immunosuppression on pre-existing cancers. Transplantation 1993, 55, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annese, V.; Beaugerie, L.; Egan, L.; Biancone, L.; Bolling, C.; Brandts, C.; Dierickx, D.; Dummer, R.; Fiorino, G.; Gornet, J.M.; et al. European Evidence-based Consensus: Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Malignancies. J. Crohns Colitis 2015, 9, 945–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.; Biancone, L.; Fiorino, G.; Katsanos, K.H.; Kopylov, U.; Al Sulais, E.; Axelrad, J.E.; Balendran, K.; Burisch, J.; de Ridder, L.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Malignancies. J. Crohns Colitis 2023, 17, 827–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzkowitz, S.H.; Jiang, Y.; Villagra, C.; Colombel, J.F.; Sultan, K.; Lukin, D.J.; Faleck, D.M.; Scherl, E.; Chang, S.; Chen, L.; et al. Safety of Immunosuppression in a Prospective Cohort of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with a History of Cancer: SAPPHIRE Registry. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 23, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Population (n = 122) | New/Recurrent Cancer (n = 12) | No new/Recurrent Cancer (n = 110) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median [range] | 59.5 [26–89] | 59 [27–86] | 60 [26–89] | 0.42 |

| Age at diagnosis of cancer, median [range] | 50.5 [2–79] | 48 [17–79] | 51 [2–75] | 0.57 |

| Gender (F), n (%) | 58 (47.5) | 4 (33.3) | 54 (49.1) | 0.29 |

| IBD duration, median [range] | 13.5 [1–59] | 12 [8–45] | 16 [1–59] | 0.59 |

| Time interval from first to second cancer, median [range] | 60 [3–183] | 60 [3–183] | n.a. | n.a. |

| Time between ISSs/biologics and second cancer, median [range] | 38.5 [3–108] | 38.5 [3–108] | n.a. | n.a. |

| Follow-up after cancer, median [range] | 8 [1–45] | 9 [3–15] | 7 [1–45] | 0.95 |

| Death, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | n.a. |

| Active smoking (yes at enrollment) | 44 (36.1) | 3 (25) | 41 (37.3) | 0.6 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, n (%) | 24 (19.7) | 1 (8.3) | 23 (20.9) | 0.51 |

| Age at diagnosis of IBD | ||||

| ≤16 years | 6/122 (4.9) | 1/12 (8.3) | 5/110 (4.5) | 0.89 |

| >17 and ≤40 years | 58/122 (47.5) | 6/12 (50) | 52/110 (47.3) | 0.95 |

| 40 years | 58/122 (47.5) | 5/12 (41.7) | 53/110 (48.2) | 0.9 |

| UC | 38 (31.1) | 4 (33.3) | 34 (30.9) | 1.0 |

| E1 | 2/38 (5.3) | 0/4 (0) | 2/34 (5.8) | n.a. |

| E2 | 13/38 (34.2) | 2/4 (50) | 11/34 (32.4) | 0.83 |

| E3 | 23/38 (60.5) | 2/4 (50) | 21/34 (61.8) | 0.85 |

| CD | 84 (68.9) | 8 (66.7) | 76 (69.1) | 0.87 |

| L1 | 50/84 (59.5) | 2/8 (25) | 48/76 (63.2) | 0.13 |

| L2 | 4/84 (4.8) | 1/8 (12.5) | 3/76 (3.9) | 0.85 |

| L3 | 30/84 (35.7) | 5/8 (62.5) | 25/76 (32.9) | 0.27 |

| L4 | 7/84 (8.3) | 1/8 (12.5) | 6/76 (7.9) | 0.81 |

| B1 | 24/84 (28.6) | 2/8 (25) | 22/76 (28.9) | 0.91 |

| B2 | 45/84 (53.6) | 5/8 (62.5) | 40/76 (52.6) | 0.96 |

| B3 | 15/84 (17.8) | 1/8 (12.5) | 14/76 (18.5) | 0.98 |

| Perianal Disease, n (%) | 17/84 (20.2) | 2/8 (25) | 15/76 (19.7) | 0.88 |

| Immunosuppressors | Biologics | Small Molecules | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBD Patients, n= | 41 | 46 | 1 | ||||

| Thiopurines (n = 35) | Methotrexate (n = 5) | Others (n = 3) | TNFi (n = 40) | Vedolizumab (n = 10) | Ustekinumab (n = 4) | Tofacitinib (n = 1) | |

| Duration, median [range], months | 38 [3–228] | 36 [3–89] | 66 [36–96] | 36 [3–180] | 10.5 [3–63] | 42.5 [1–58] | 18 [18] |

| Immunosuppressors | Biologics | Small Molecules | |||||

| CD patients, n= | 32 | 34 | 0 | ||||

| Thiopurines (n = 28) | Methotrexate (n = 5) | Others (n = 1) | TNFi (n = 30) | Vedolizumab (n = 5) | Ustekinumab (n = 4) | Tofacitinib (n = 0) | |

| Duration, median [range] months | 38.5 [3–228] | 36 [3–89] | 96 [96–96] | 32 [30–180] | 9 [3–63] | 21.5 [1–48] | n.a. |

| Immunosuppressors | Biologics | Small Molecules | |||||

| UC patients, n= | 9 | 12 | 1 | ||||

| Thiopurines (n = 7) | Methotrexate (n = 0) | Others (n = 2) | TNFi (n = 10) | Vedolizumab (n = 0) | Ustekinumab (n = 5) | Tofacitinib (n = 1) | |

| Duration, median [range] months | 35 [3–72] | n.a. | 66 [36–96] | 24 [8–108] | n.a. | 14 [3–24] | 18 [18–18] |

| Index Cancer | IBD (n = 122) | CD (n = 84) | UC (n = 38) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin cancer, n (%) | 31 (25.4) | 21 (25) | 10 (26.3) | 0.87 |

| Non-melanoma skin cancer, n (%) | 17 (13.9) | 12 (14.3) | 5 (13.2) | 0.87 |

| Basal cell carcinoma, n | 15 | 10 | 5 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma, n | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Melanoma, n (%) | 14 (11.4) | 9 (10.7) | 5 (13.2) | 0.69 |

| Genitourinary, n (%) | 18 (14.8) | 14 (16.7) | 4 (10.5) | 0.54 |

| Wilms tumor, n | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Renal oncocytoma, n | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Urinary tract carcinoma, n | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Renal cell carcinoma, n | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Testicular seminoma, n | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Gland squamous cell carcinoma, n | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Prostate adenocarcinoma, n (%) | 8 (6.6) | 5 (6) | 3 (7.9) | 0.99 |

| Breast adenocarcinoma, n (%) | 15 (12.3) | 9 (10.7) | 6 (15.8) | 0.42 |

| Thyroid, n (%) | 13 (10.7) | 10 (11.9) | 3 (7.9) | 0.72 |

| Papillary carcinoma, n | 11 | 10 | 1 | |

| Follicular carcinoma, n | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma, n (%) | 11 (9.0) | 6 (7.1) | 5 (13.2) | 0.28 |

| Hematopoietic, n (%) | 9 (7.4) | 7 (8.3) | 2 (5.3) | 0.82 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, n | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Myeloid acute leukemia, n | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Myeloma, n | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Essential thrombocythemia, n | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Granulocytic dysplasia, n | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Neuroendocrine tumors, n (%) | 4 (3.3) | 3 (3.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0.78 |

| Head–neck cancer, n (%) | 3 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (5.3) | 0.47 |

| Larynx, n | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Salivary glands adenocarcinoma, n | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Pharynx squamous cell carcinoma, n | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Liver, n (%) | 3 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (5.3) | 0.47 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma, n | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Gallbladder adenocarcinoma, n | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Endometrial adenocarcinoma, n (%) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (2.4) | 0 | n.a. |

| Lung adenocarcinoma, n (%) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | n.a. |

| Others, n (%) | 4 (3.3) | 3 (3.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0.78 |

| Pituitary adenoma, n | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Thoracic ganglioneuroma, n | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Liposarcoma, n | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Low grade sarcoma, n | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Immunosuppressors | Biologics | Small Molecules | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBD patients, n= | 27 | 113 | 9 | |||||||||

| Thiopurines (n = 10) | MTX (n = 14) | Others (n = 3) | TNFi (n = 36) | VDZ (n = 60) | UST (n = 45) | RISA (n = 5) | SECUK (n = 1) | TOFA (n = 3) | FILGO (n = 1) | UPA (n = 4) | OZA (n = 1) | |

| Duration, median [range], months | 33.5 [4–200] | 31 [16–40] | 72 [60–108] | 38 [3–180] | 24 [3–84] | 24 [3–66] | 6 [3–12] | 48 [48–48] | 17 [3–18] | 12 [12–12] | 6 [5–6] | 4 [4–4] |

| Immunosuppressors | Biologics | Small Molecules | ||||||||||

| CD Patients, n= | 19 | 76 | 2 | |||||||||

| Thiopurines (n = 10) | MTX (n = 8) | Others (n = 1) | TNFi (n = 29) | VDZ (n = 33) | UST (n = 35) | RISA (n = 5) | SECUK (n = 0) | TOFA (n = 0) | FILGO (n = 0) | UPA (n = 2) | OZA (n = 0) | |

| Duration, median [range], months | 33.5 [4–200] | 31 [16–40] | 72 [72–72] | 39 [3–180] | 21 [3–72] | 24 [6–66] | 6 [3–12] | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Immunosuppressors | Biologics | Small Molecules | ||||||||||

| UC Patients, n= | 8 | 37 | 7 | |||||||||

| Thiopurines (n = 0) | MTX (n = 6) | Others (n = 2) | TNFi (n = 7) | VDZ (n = 28) | UST (n = 10) | RISA (n = 0) | SECUK (n = 1) | TOFA (n = 3) | FILGO (n = 1) | UPA (n = 2) | OZA (n = 1) | |

| Duration, median [range], months | n.a. | 15.5 [6–131] | 84 [60–108] | 29 [5–39] | 24 [3–60] | 18.5 [3–24] | n.a. | 48 [48–48] | 17 [3–18] | 12 [12–12] | 6 [6–6] | 4 [4–4] |

| Pts. | IBD Features | Age at IBD Diagnosis (Years) | Age at Cancer Diagnosis (Years) | Index Cancer | ISSs Before Index Cancer: Type (Duration, mos) | Biologics Before Index Cancer: Type (Duration, mos) | ISS Treatment After Index Cancer, Duration (mos) | Biologic Use After Index Cancer, Duration (mos) | Time Interval from Index Cancer to IMMs (mos) | New Cancer | Recurrent Cancer | Time Interval from Biologics to New/ Recurrent Cancer | Time Interval from New/Recurrent Cancer to Previous Cancer (mos) | Follow-Up Duration After Index Cancer (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CD, L3 B2 | 21 | 29 | Thyroid | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | ADA (96) | 36 | n.a. | Thyroid | 0 | 12 | 10 |

| 2 | CD, L1, B2 | 16 | 17 | Melanoma | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | ADA (9) | 6 | Melanoma | n.a. | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| 3 | CD, L1/L4, B2 | 22 | 29 | NMSC | AZA (72) | IFX (3) | n.a. | UST (14) | 6 | NMSC | n.a. | 14 | 168 | 15 |

| 4 | CD, L3, B3, p | 18 | 57 | Prostate NMSC | n.a. | IFX (84) VDZ (12) | n.a. | VDZ (16) UST (42) | 6 | NMSC | Prostate | 16 | 24 | 5 |

| 5 | CD, L3, B1, p | 46 | 41 | Thyroid | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | VDZ (53) | 132 | n.a. | Thyroid | 53 | 183 | 15 |

| 6 | UC, E3 | 55 | 55 | HCC | n.a | n.a. | Tacrolimus/ Everolimus (108) | VDZ (10) | 96 | Salivary gland carcinoma NMSC | n.a. | 96 | 96 | 8 |

| 7 | UC, E3 | 74 | 79 | Prostate | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | VDZ (41) | 12 | n.a. | Prostate | 41 | 53 | 7 |

| 8 | UC, E2 | 25 | 48 | CRC | n.a. | n.a. | MTX (26) | VDZ (9) | 24 ISS 60 BIO | n.a. | CRC | 10 | 60 | 9 |

| 9 | CD L3 B2 | 52 | 57 | NMSC | AZA (36) | n.a. | n.a. | ADA (60) | 12 | NMSC | n.a. | 48 | 60 | 6 |

| 10 | CD, L3, B2 | 29 | 64 | NMSC | AZA (24) | IFX (12) ADA (84) | n.a. | ADA (120) | 3 | NMSC | n.a. | 108 | 108 | 3 |

| 11 | UC, E2 | 60 | 59 | Renal cell carcinoma | n.a. | n.a. | MTX (108) | VDZ (31) TOFA (17) | 144 | NMSC | n.a. | 36 | 180 | 11 |

| 12 | CD, L2, B1 | 19 | 33 | Melanoma | AZA (228) | IFX (2) ADA (3) | n.a. | VDZ (3) UST (23) | 72 | Melanoma NMSC | n.a. | 8 | 60 | 8 |

| IMMs Before Index Cancer | New/Recurrent Cancer (n = 12) | No new/Recurrent Cancer (n = 110) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISSs, n (%) | 6 (50) | 35 (31.8) | 0.48 |

| Thiopurines | 4 (66.6) | 30 (85.7) | 0.93 |

| Methotrexate | 1 (16.7) | 4 (11.4) | 0.96 |

| Other | 1 (16.7) | 3 (8.6) | 0.9 |

| ISS duration, median [range] | |||

| Thiopurines | 54 [24–228] | 38 [3–156] | 0.11 |

| Methotrexate | 3 [3–3] | 45.5 [12–89] | 0.06 |

| Others | 96 [96–96] | 19.5 [3–96] | n.a. |

| Biologics/JAKi, n (%) | 6 (50) | 40 (36.4) | 0.71 |

| TNFi | 6 (100) | 34 (85) | 0.43 |

| Vedolizumab | 1 (16.6) | 9 (22.5) | 0.64 |

| Ustekinumab | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | n.a. |

| Tofacitinib | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | n.a. |

| Biologics/JAKi duration median, [range] | |||

| TNFi | 46.5 [3–96] | 36 [6–180] | 0.85 |

| Vedolizumab | 12 [12–12] | 6.5 [3–63] | 0.55 |

| Ustekinumab | 0 | 19 [1–37] | n.a. |

| Tofacitinib | 0 | 18 [18–18] | n.a. |

| New/Recurrent Malignancy (n = 12) | No new/Recurrent Malignancy (n = 110) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISSs after cancer, n (%) | 4 (30.8) | 23 (21.1) | 0.65 |

| Thiopurines | 1 (25) | 9 (39.1) | 0.64 |

| Methotrexate | 2 (50) | 12 (52.3) | 0.99 |

| Others | 1 (25) | 2 (8.7) | 0.73 |

| ISS duration after cancer, median [range] | 25.5 [12–108] | 33 [4–200] | 0.24 |

| Thiopurines | n.a. | 42 [4–200] | n.a. |

| Methotrexate | n.a. | 24.5 [6–131] | n.a. |

| Others | n.a. | 66 [60–72] | n.a. |

| Biologics after cancer, n (%) | |||

| TNFi | 5 (38.5) | 31 (31.3) | 0.66 |

| Vedolizumab | 8 (61.5) | 52 (51.5) | 0.73 |

| Ustekinumab | 5 (35.5) | 40 (40.4) | 0.85 |

| Risankizumab | 0 (0) | 5 (5) | n.a. |

| Secukinumab | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | n.a. |

| JAKi after cancer, n (%) | 1 (7.7) | 8 (7.3) | |

| Tofacitinib | 1 (7.7) | 2 (2) | n.a. |

| Filgotinib | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | n.a. |

| Upadacitinib | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | n.a. |

| Ozanimod | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | n.a. |

| Biologic duration after neoplasia, median [range] | |||

| TNFi | 84 [9–120] | 36 [3–180] | 0.17 |

| Vedolizumab | 13 [3–53] | 24 [3–84] | 0.36 |

| Ustekinumab | 14 [12–42] | 24 [3–66] | 0.34 |

| Risankizumab | 0 | 6 [3–12] | n.a. |

| Secukinumab | 0 | 48 [48–48] | n.a. |

| JAKi duration after neoplasia, median [range] | |||

| Tofacitinib | 17 [17–17] | 17 [3–18] | n.a. |

| Filgotinib | n.a. | 12 [12–12] | n.a. |

| Upadacitinib | n.a. | 6 [5–6] | n.a. |

| Ozanimod | n.a. | 4 [4–4] | n.a. |

| OR [CI 95%] | p | |

|---|---|---|

| ISSs after index cancer | 1.66 [0.46–5.88] | 0.43 |

| ISSs before index cancer | 1.81 [0.56–5.79] | 0.31 |

| Biologics before index cancer | 1.47 [0.46–4.7] | 0.51 |

| Age at diagnosis of cancer | 0.98 [0.95–1.02] | 0.58 |

| Active smoking | 0.49 [0.12–1.91] | 0.3 |

| Gender (F) | 0.45 [0.13–1.55] | 0.2 |

| IBD type (CD) | 1.57 [0.4–6.1] | 0.5 |

| TNFis after index cancer | 1.39 [0.42–4.59] | 0.58 |

| ISS duration after index cancer | 0.6 [0.07–5.07] | 0.64 |

| ISS duration before index cancer | 1.51 [0.37–6.06] | 0.55 |

| TNFi duration after index cancer | 3.01 [0.81–11.11] | 0.09 |

| TNFi duration before index cancer | 1.62 [0.4–6.51] | 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mancone, R.; Neri, B.; De Francesco, C.; Bonacci, L.; Fiorillo, M.; Schiavone, S.C.; Galbusera, A.; Sparacino, A.; Testa, A.; Orlando, A.; et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with a History of Cancer: Safety of Immunomodulators in a Multicenter Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 3293. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17203293

Mancone R, Neri B, De Francesco C, Bonacci L, Fiorillo M, Schiavone SC, Galbusera A, Sparacino A, Testa A, Orlando A, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with a History of Cancer: Safety of Immunomodulators in a Multicenter Study. Cancers. 2025; 17(20):3293. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17203293

Chicago/Turabian StyleMancone, Roberto, Benedetto Neri, Clara De Francesco, Livio Bonacci, Mariasofia Fiorillo, Sara Concetta Schiavone, Anna Galbusera, Alba Sparacino, Anna Testa, Ambrogio Orlando, and et al. 2025. "Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with a History of Cancer: Safety of Immunomodulators in a Multicenter Study" Cancers 17, no. 20: 3293. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17203293

APA StyleMancone, R., Neri, B., De Francesco, C., Bonacci, L., Fiorillo, M., Schiavone, S. C., Galbusera, A., Sparacino, A., Testa, A., Orlando, A., Calabrese, E., Marafini, I., Festa, S., Castiglione, F., Fries, W., Monteleone, G., & Biancone, L. (2025). Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with a History of Cancer: Safety of Immunomodulators in a Multicenter Study. Cancers, 17(20), 3293. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17203293