Is YouTube™ a Reliable Source of Information for the Current Use of HIPEC in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer?

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

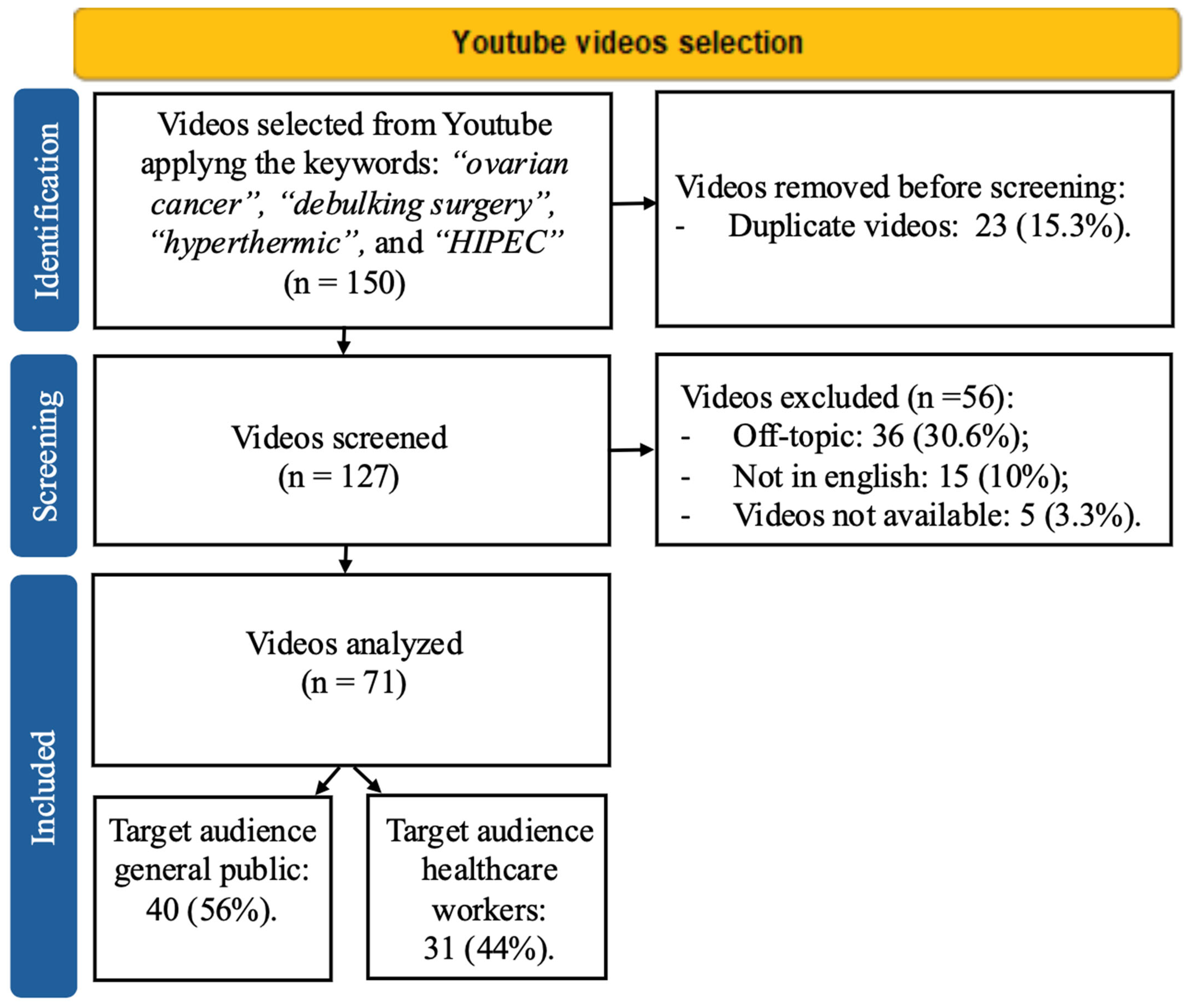

2.1. Video Search and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Strategies and Tools for Video Content Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, D.M.; Neighbors, J.; Perhanidis, J.; Monk, B.J. Gastrointestinal symptoms and diagnosis preceding ovarian cancer diagnosis: Effects on treatment allocation and potential diagnostic delay. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledermann, J.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Amant, F.; Concin, N.; Davidson, B.; Fotopoulou, C.; González-Martin, A.; Gourley, C.; Leary, A.; Lorusso, D.; et al. ESGO–ESMO–ESP consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: Pathology and molecular biology and early, advanced and recurrent disease. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaillard, S.; Lacchetti, C.; Armstrong, D.K.; Cliby, W.A.; Edelson, M.I.; Garcia, A.A.; Ghebre, R.G.; Gressel, G.M.; Lesnock, J.L.; Meyer, L.A.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Newly Diagnosed, Advanced Ovarian Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 868–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, A.M.; Coada, C.A.; Ravegnini, G.; De Leo, A.; Damiano, G.; De Crescenzo, E.; Tesei, M.; Di Costanzo, S.; Genovesi, L.; Rubino, D.; et al. Post-operative residual disease and number of cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsinejad, S.; Cattabiani, T.; Muranen, T.; Iwanicki, M. Ovarian Cancer Dissemination—A Cell Biologist’s Perspective. Cancers 2019, 11, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.P.; Madhusoodanan, M.; Pangath, M.; Menon, D. Innovative landscapes in intraperitoneal therapy of ovarian cancer. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 1877–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Driel, W.J.; Koole, S.N.; Sikorska, K.; Schagen van Leeuwen, J.H.; Schreuder, H.W.R.; Hermans, R.H.M.; De Hingh, I.H.; Van Der Velden, J.; Arts, H.J.; Massuger, L.F.; et al. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.C. CHIPOR, HORSE, and beyond: Unraveling the role of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in ovarian cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2025, 36, e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagotti, A.; Costantini, B.; Fanfani, F.; Giannarelli, D.; De Iaco, P.; Chiantera, V.; Mandato, V.; Giorda, G.; Aletti, G.; Greggi, S.; et al. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Platinum-Sensitive Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: A Randomized Trial on Survival Evaluation (HORSE; MITO-18). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivanovic, O.; Chi, D.S.; Zhou, Q.; Iasonos, A.; Konner, J.A.; Makker, V.; Grisham, R.N.; Brown, A.K.; Nerenstone, S.; Diaz, J.P.; et al. Secondary Cytoreduction and Carboplatin Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Platinum-Sensitive Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: An MSK Team Ovary Phase II Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2594–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classe, J.-M.; Meeus, P.; Hudry, D.; Wernert, R.; Quenet, F.; Marchal, F.; Houvenaeghel, G.; Bats, A.-S.; Lecuru, F.; Ferron, G.; et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for recurrent ovarian cancer (CHIPOR): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 1551–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Corte, L.; Conte, C.; Palumbo, M.; Guerra, S.; Colacurci, D.; Riemma, G.; De Franciscis, P.; Giampaolino, P.; Fagotti, A.; Bifulco, G.; et al. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC): New Approaches and Controversies on the Treatment of Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer-Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koole, S.; van Stein, R.; Sikorska, K.; Barton, D.; Perrin, L.; Brennan, D.; Zivanovic, O.; Mosgaard, B.J.; Fagotti, A.; Colombo, P.-E.; et al. Primary cytoreductive surgery with or without hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for FIGO stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: OVHIPEC-2, a phase III randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.omnicoreagency.com/youtube-statistics/ (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Kumar, N.; Pandey, A.; Venkatraman, A.; Garg, N. Are video sharing Web sites a useful source of information on hypertension? J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2014, 8, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morra, S.; Ruvolo, C.C.; Napolitano, L.; La Rocca, R.; Celentano, G.; Califano, G.; Creta, M.; Capece, M.; Turco, C.; Cilio, S.; et al. YouTubeTM as a source of information on bladder pain syndrome: A contemporary analysis. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2022, 41, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bello, F.; Ruvolo, C.C.; Cilio, S.; La Rocca, R.; Capece, M.; Creta, M.; Celentano, G.; Califano, G.; Morra, S.; Iacovazzo, C.; et al. Testicular cancer and YouTube: What do you expect from a social media platform? Int. J. Urol. 2022, 29, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvolo, C.C.; Califano, G.; Tuccillo, A.; Tolentino, S.; Cancelliere, E.; Di Bello, F.; Celentano, G.; Creta, M.; Longo, N.; Morra, S.; et al. “YouTube™ as a source of information on placenta accreta: A quality analysis”. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 272, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilio, S.; Ruvolo, C.C.; Turco, C.; Creta, M.; Capece, M.; La Rocca, R.; Celentano, G.; Califano, G.; Morra, S.; Melchionna, A.; et al. Analysis of quality information provided by “Dr. YouTubeTM” on Phimosis. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2023, 35, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, S.J.; Wolf, M.S.; Brach, C. Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): A new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 96, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Audiovisual Content (PEMAT A/V). Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/patient-education/pemat2.html (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Charnock, D.; Shepperd, S.; Needham, G.; Gann, R. DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1999, 53, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The DISCERN questionnaire. Available online: https://www.ndph.ox.ac.uk/research/research-groups/applied-health-research-unit-ahru/discern (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Lim, M.C.; Chang, S.-J.; Park, B.; Yoo, H.J.; Yoo, C.W.; Nam, B.H.; Park, S.-Y.; Collaborators, H.F.O.C.; Seo, S.-S.; Kang, S.; et al. Survival After Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy and Primary or Interval Cytoreductive Surgery in Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, E.; Taylor, A.; Andreou, A.; Ang, C.; Arora, R.; Attygalle, A.; Banerjee, S.; Bowen, R.; Buckley, L.; Burbos, N.; et al. British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) ovarian, tubal and primary peritoneal cancer guidelines: Recommendations for practice update 2024. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 300, 69–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Shimada, M.; Tamate, M.; Cho, H.W.; Zhu, J.; Chou, H.-H.; Kajiyama, H.; Okamoto, A.; Aoki, D.; Kang, S.; et al. Current treatment strategies for ovarian cancer in the East Asian Gynecologic Oncology Trial Group (EAGOT). J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 35, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, H.; Mikami, M.; Nagase, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tabata, T.; Kaneuchi, M.; Satoh, T.; Hirashima, Y.; Matsumura, N.; Yokoyama, Y.; et al. The 2020 Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology guidelines for the treatment of ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and primary peritoneal cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 32, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Chun, S.-Y.; Lee, D.-E.; Woo, Y.H.; Chang, S.-J.; Park, S.-Y.; Chang, Y.J.; Lim, M.C. Cost-effectiveness of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy following interval cytoreductive surgery for stage III-IV ovarian cancer from a randomized controlled phase III trial in Korea (KOV-HIPEC-01). Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 170, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurlu, G.A.; Ugurlu, B.N. Evaluating the quality and reliability of youtube videos on tympanostomy tubes: A comprehensive analysis for patients and parents. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, M.; Reyhan, A.H. A Quality Assessment of YouTube Videos on Chalazia: Implications for Patient Education and Healthcare Professional Involvement. Cureus 2025, 17, e78043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchionna, A.; Ruvolo, C.C.; Capece, M.; La Rocca, R.; Celentano, G.; Califano, G.; Creta, M.; Napolitano, L.; Morra, S.; Cilio, S.; et al. Testicular pain and youtube™: Are uploaded videos a reliable source to get information? Int. J. Impot. Res. 2023, 35, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezone, G.; Ruvolo, C.C.; Cilio, S.; Fraia, A.; Di Mauro, E.; Califano, G.; Passaro, F.; Creta, M.; Capece, M.; La Rocca, R.; et al. The spreading information of YouTube videos on Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors: A worrisome picture from one of the most consulted internet source. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2024, 36, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morra, S.; Napolitano, L.; Ruvolo, C.C.; Celentano, G.; La Rocca, R.; Capece, M.; Creta, M.; Passaro, F.; Di Bello, F.; Cirillo, L.; et al. Could YouTubeTM encourage men on prostate checks? A contemporary analysis. Arch. Ital. Urol. Androl. 2022, 94, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhao, H. Analysis of the quality of vulvar cancer-related videos on YouTube. Transl. Cancer Res. 2025, 14, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meci, A.; Bollig, C.; Tseng, C.C.; Goyal, N. Evaluating YouTube Videos for Resident Education in Free Flap Surgery. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2025, 10, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marra, A.; de Siena, A.U.; Iacovazzo, C.; Vargas, M.; Cesarano, N.; Ruvolo, C.C.; Celentano, G.; Buonanno, P. Impact of YouTube® videos on knowledge on tracheal intubation for anesthesiologist trainees: A prospective observational study. J. Anesthesia Analg. Crit. Care 2025, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mahrouk, M.; Jaradat, D.; Eichler, T.; Sucher, R.; Margreiter, C.; Lederer, A.; Karitnig, R.; Geisler, A.; Jahn, N.; Hau, H.M. “YouTube” for Surgical Training and Education in Donor Nephrectomy: Friend or Foe? J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2025, 12-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, L.; Monkman, H.; Fullerton, C. Exploring Older Adult Cancer Survivors’ Digital Information Needs: Qualitative Pilot Study. JMIR Cancer 2025, 11, e59391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, L.Q.; Koranyi, S.; Engelmann, D.; Philipp, R.; Scheffold, K.; Schulz-Kindermann, F.; Härter, M.; Mehnert, A. Perceived doctor-patient relationship and its association with demoralization in patients with advanced cancer. Psycho Oncol. 2018, 27, 2587–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzielli, G.; Giudice, M.T.; Nardelli, F.; Costantini, B.; Salutari, V.; Inzani, F.S.; Zannoni, G.F.; Chiantera, V.; Di Giorgio, A.; Pacelli, F.; et al. Pressurized IntraPeritoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) Applied to Platinum-Resistant Recurrence of Ovarian Tumor: A Single-Institution Experience (ID: PARROT Trial). Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Overall, n = 71 1 | TARGET.AUDIENCE General Public, n = 40 (56%) 1 | TARGET.AUDIENCE Healthcare Workers, n = 31 (44%) 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of the video (seconds) | 285 (141, 695) | 174 (113, 314) | 710 (304, 2533) | <0.001 |

| Views (n) | 608 (244, 2085) | 743 (345, 3684) | 425 (213, 1064) | 0.069 |

| Author Sex | 0.107 | |||

| Male | 39 (55%) | 18 (58%) | 21 (53%) | |

| Female | 19 (27%) | 6 (19%) | 13 (33%) | |

| Both | 10 (14%) | 7 (23%) | 3 (7.5%) | |

| No voice | 3 (4.2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Continent of Origin | 0.233 | |||

| North America | 31 (48%) | 13 (42%) | 18 (53%) | |

| Asia | 23 (35%) | 9 (29%) | 14 (41%) | |

| Europe | 4 (6.2%) | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Africa | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Mixed origin | 6 (9.2%) | 5 (16.2%) | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Unknown | 6 | 0 | 6 | |

| Duration Day on YouTube (days) | 1269 (809, 2260) | 1497 (669, 2465) | 1257 (1173, 2068) | >0.9 |

| Likes (n) | 6 (2, 16) | 8 (3, 24) | 4 (2, 10) | 0.094 |

| Likes/views ratio | 0.008 (0.004, 0.012) | 0.009 (0.006, 0.015) | 0.006 (0.004, 0.010) | 0.202 |

| Subscribers (n) | 10,500 (1361, 29,350) | 10,500 (801, 58,975) | 10,800 (1920, 22,600) | 0.7 |

| Comments (n) | 0.8 | |||

| abled | 58 (82) | 33 (83) | 25 (81) | |

| disabled (as per YouTube policy) | 13 (18) | 7 (18) | 6 (19) | |

| Comments/views ratio | 0 (0.0000, 0.0010) | 0 (0.0000, 0.0005) | 0 (0.0000, 0.0013) | 0.320 |

| Unknown | 13 | 7 | 6 | |

| Author group (n) | 0.5 | |||

| General public | 10 (14) | 7 (18) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Healthcare workers | 61 (86) | 33 (83) | 28 (90) |

| Characteristic | Overall, n = 71 1 | TARGET.AUDIENCE General Public, n = 40 (56%) 1 | TARGET.AUDIENCE Healthcare Workers, n = 31 (44%) 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEMAT_UNDERSTANDABILITY (%) | 80 (62, 90) | 80 (63, 94) | 77 (62, 88) | 0.15 |

| PEMAT_ACTIONABILITY (%) | 33 (25, 100) | 33 (19, 100) | 50 (33, 88) | 0.4 |

| DISCERN_Section 1 (n) | 27 (20, 33) | 21 (17, 27) | 32 (28, 35) | <0.001 |

| DISCERN_Section 2 (n) | 19 (16, 24) | 17 (11, 22) | 21 (17, 26) | 0.001 |

| DISCERN_total score (n) | 50 (35, 60) | 40 (32, 52) | 56 (51, 64) | <0.001 |

| MISINFORMATION_Score (n) | 2.00 (1.00, 3.50) | 1.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 3.00 (3.00, 5.00) | <0.001 |

| Q1. In which clinical scenarios should HIPEC be considered? | 50 (71.43) | 19 (38) | 31 (62) | |

| Q2. What are the potential complications associated with the HIPEC procedure? | 23 (32.39) | 5 (21.74) | 18 (78.26) | |

| Q3 Should HIPEC be performed in high-volume centers with specialized expertise? | 28 (39.44) | 8 (28.57) | 20 (40) | |

| Q4. Is the impact of HIPEC on survival outcomes clarified? | 41 (57.75) | 16 (9.02) | 25 (60.98) | |

| Q5. Should HIPEC be offered only within the context of a randomized controlled trial (RCT)? | 17 (23.94) | 1 (5.88) | 15 (88.24) | |

| GLOBAL_QUALITY_SCORE | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 7 (9.9) | 7 (18) | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 13 (18) | 12 (30) | 1 (3.2) | |

| 3 | 21 (30) | 13 (33) | 8 (26) | |

| 4 | 25 (35) | 8 (20) | 17 (55) | |

| 5 | 5 (7.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (16) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mezzapesa, F.; Bilancia, E.P.; Afonina, M.; Di Costanzo, S.; Masina, E.; De Iaco, P.; Perrone, A.M. Is YouTube™ a Reliable Source of Information for the Current Use of HIPEC in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer? Cancers 2025, 17, 3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193222

Mezzapesa F, Bilancia EP, Afonina M, Di Costanzo S, Masina E, De Iaco P, Perrone AM. Is YouTube™ a Reliable Source of Information for the Current Use of HIPEC in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer? Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193222

Chicago/Turabian StyleMezzapesa, Francesco, Elisabetta Pia Bilancia, Margarita Afonina, Stella Di Costanzo, Elena Masina, Pierandrea De Iaco, and Anna Myriam Perrone. 2025. "Is YouTube™ a Reliable Source of Information for the Current Use of HIPEC in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer?" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193222

APA StyleMezzapesa, F., Bilancia, E. P., Afonina, M., Di Costanzo, S., Masina, E., De Iaco, P., & Perrone, A. M. (2025). Is YouTube™ a Reliable Source of Information for the Current Use of HIPEC in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer? Cancers, 17(19), 3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193222