The Mistletoe and Breast Cancer (MAB) Study: A UK Mixed-Phase, Pilot, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Sample Size and Site

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Randomisation and Blinding

2.5. Mistletoe Therapy (Intervention Group)

2.6. Placebo (Control Group)

2.7. Data Collection

2.7.1. Recruitment

- Recruitment rate.

- Obstacles to recruitment.

2.7.2. Retention and Adherence

- Attrition rate with reasons, if possible.

- Acceptability of regular subcutaneous injections.

- Adherence to the study therapy schedule.

- Assessment of therapy-related symptoms and health-related quality of life in the sample population.

- Completion of outcome measures.

2.7.3. Blinding

- Assessment of blinding of patients.

2.7.4. Adverse Events

- Adverse events from MT and placebo subcutaneous injections.

2.8. Clinical Study Data

2.8.1. Participant Diaries

2.8.2. Questionnaire Pack

2.8.3. Adverse Events

2.8.4. Qualitative Interviews

2.9. Data Analysis

2.10. MAB Management

2.11. Patient and Public Involvement

3. Results

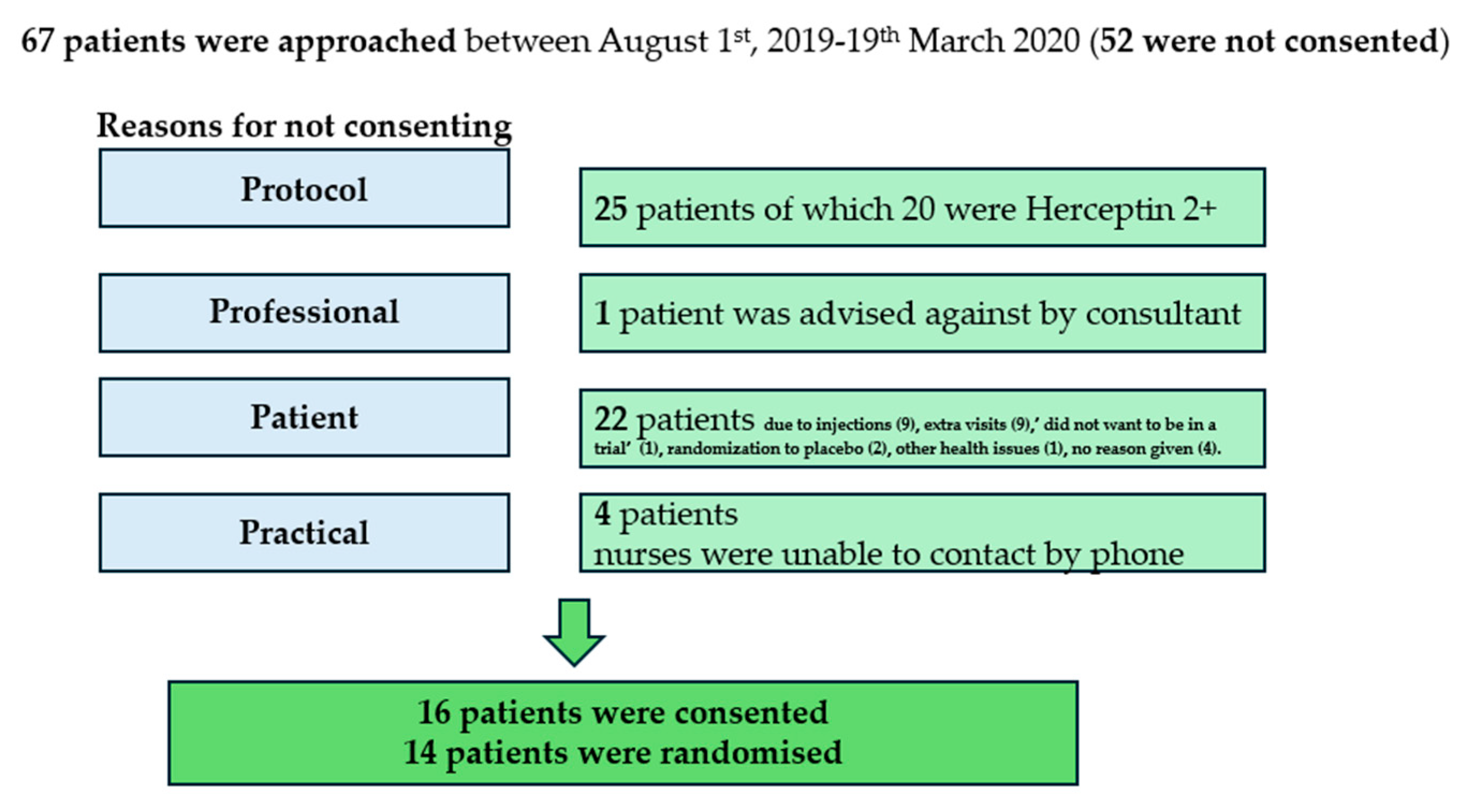

3.1. Recruitment

3.1.1. Barriers to Recruitment

3.1.2. Enablers to Recruitment

3.2. Retention and Adherence

3.2.1. Barriers to Retention and Adherence

3.2.2. Enablers to Retention and Adherence

3.3. Assessment of Blinding

3.4. Adverse Events

3.5. Quality-of-Life Questionnaire

3.6. Outcome Data

3.7. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Beliefs

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Implications for Clinical Practice and Further Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mistletoe Therapy: Information for Doctors. Available online: https://www.mistletoe-therapy.org/information-for-doctors (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- EMA Report on Mistletoe Therapy. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/herbal-report/final-assessment-report-viscum-album-l-herba_en.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- FDA Report on Mistletoe Therapy. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/patient/mistletoe-pdq (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Schnell-Inderst, P.; Steigenberger, C.; Mertz, M.; Otto, I.; Flatscher-Thöni, M.; Siebert, U. Additional treatment with mistletoe extracts for patients with breast cancer compared to conventional cancer therapy Alone—Efficacy and safety, costs and cost-effectiveness, patients and social aspects, and ethical assessment. Ger. Med. Sci. 2022, 20, Doc10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistletoe Centres in the UK. Available online: https://www.mistletoetherapy.org.uk/centres/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- NHS Long Term Plan Ambitions for Cancer. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/strategy/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- NHS Guidance on Herbal Medicine During Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/tests-and-treatments/herbal-medicines/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Bryant, S.; Duncan, L.; Feder, G.; Huntley, A.L. A pilot study of the mistletoe and breast cancer (MAB) trial: A protocol for a randomised double-blind controlled trial. Pilot. Feasibility Stud. 2022, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CONSORT Guidelines. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/consort/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- The ECOG Performance Status Scale. Available online: https://ecog-acrin.org/resources/ecog-performance-status/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; De Haes, J.C.J.M.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprangers, M.A.; Groenvold, M.; Arraras, J.I.; Franklin, J.; te Velde, A.; Muller, M.; Franzini, L.; Williams, A.; De Haes, H.C.; Hopwood, P.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: First results from a three-country field study. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996, 14, 2756–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.I.; Beaumont, J.L.; Ding, B.; Malin, J.; Peterman, A.; Calhoun, E.; Cella, D. Measuring health-related quality of life and neutropenia-specific concerns among older adults undergoing chemotherapy: Validation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Neutropenia (FACT-N). Support. Care Cancer 2007, 16, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, T.; Akechi, T.; Kugaya, A.; Okamura, H.; Shima, Y.; Maruguchi, M.; Hosaka, T.; Uchitomi, Y. Development and validation of the cancer fatigue scale: A brief, three-dimensional, self-rating scale for assessment of fatigue in cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2000, 19, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröz, M.; Feder, G.; von Laue, H.; Zerm, R.; Reif, M.; Girke, M.; Matthes, H.; Gutenbrunner, C.; Heckmann, C. Validation of a questionnaire measuring the regulation of autonomic function. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2008, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, F.; Yardley, L.; Lewith, G. Developing a measure of treatment beliefs: The complementary and alternative medicine beliefs inventory. Complement. Ther. Med. 2005, 13, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. Available online: https://dctd.cancer.gov/research/ctep-trials/for-sites/adverse-events/ctcae-v5-5x7.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What Can “Thematic Analysis” Offer Health and Wellbeing Researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Wellbeing 2014, 9, 26152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Breast Cancer Statistics in Men. Available online: https://www.wcrf-uk.org/preventing-cancer/uk-cancer-statistics/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Iacobucci, G. Cancer trial recruitment fell by 60% last year during pandemic. BMJ 2021, 375, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horneber, M.; Bueschel, G.; Huber, R.; Linde, K.; Rostock, M.; van Ackeren, G. Mistletoe therapy in oncology. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 2, CD003297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freuding, M.; Keinki, C.; Micke, O.; Buentzel, J.; Huebner, J. Mistletoe in oncological treatment: A systematic review. Part 1: Survival and Safety. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loef, M.; Walach, H. Quality of life in cancer patients treated with mistletoe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freuding, M.; Keinki, C.; Kutschan, S.; Micke, O.; Buentzel, J.; Huebner, J. Mistletoe in oncological treatment: A systematic review: Part 2: Quality of life and toxicity of cancer treatment. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wright, F.; Duncan, L.; Huntley, A. Profiling mistletoe therapy research and identifying evidence gaps: A systematic review of conditions treated, mode of application and outcomes. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2022, 49, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröger, W.; Ždrale, Z.; Tišma, N.; Matijašević, M. Additional Therapy with a Mistletoe Product during Adjuvant Chemotherapy of Breast Cancer Patients Improves Quality of Life: An Open Randomized Clinical Pilot Trial. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 430518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semiglasov, V.F.; Stepula, V.V.; Dudov, A.; Lehmacher, W.; Mengs, U. The standardised mistletoe extract PS76A2 im-proves QoL in patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant CMF chemotherapy: A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multi-centre clinical trial. Anticancer Res. 2004, 24, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Semiglazov, V.F.; Stepula, V.V.; Dudov, A.; Schnitker, J.; Mengs, U. Quality of life is improved in breast cancer patients by Stand-ardised Mistletoe Extract PS76A2 during chemotherapy and follow-up: A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicentre clinical trial. Anticancer Res. 2006, 26, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- UK Patient Experience. Available online: https://www.mistletoetherapy.org.uk/patient-experience/patient-stories/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Evans, M.; Bryant, S.; Huntley, A.L.; Feder, G. Cancer Patients’ Experiences of Using Mistletoe (Viscum album): A Qualitative Systematic Review and Synthesis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2016, 22, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beermann, A.; Clottu, O.; Reif, M.; Biegel, U.; Unger, L.; Koch, C. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded study comparing oral and subcutaneous administration of mistletoe extract for the treatment of equine sarcoid disease. J. Veter. Intern. Med. 2024, 38, 1815–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, J.V.D.C.; Matos, A.P.S.; Oliveria, A.P.; Júnior, E.R.; Freitas, Z.M.; Oliveira, C.A.; Toma, H.K.; Capella, M.A.M.; Rocha, L.M.; Weissenstein, U.; et al. Thermoresponsive Hydrogel Containing Viscum album Extract for Topic and Transdermal Use: Development, Stability and Cytotoxicity Activity. Pharmaceutics 2021, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean Age (yrs) | Age Range (yrs) | Identified As | Education | Occupation | Laterality | Stage | Tumour Size | Nodes | ER Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49 | 36–76 | White British = 11 White other background = 3 Chinese = 1 | No formal qualifications n = 1 Secondary n = 2 Further n = 2 Higher n = 9 | Employed n = 11 retired n = 1 unemployed due to ill health n = 1 | Right = 7 Left = 7 | Stage1 = 3 Stage2 = 9 Stage3 = 2 | T1 = 2 T2 = 12 | N0 = 7 N1 = 4 N2 = 2 N3 = 1 | ER + = 10 ER − = 4 |

| Feasibility Outcomes | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| A Recruitment | |

| Awareness of mistletoe therapy | A1 “Never heard of it before.” Participant G. A2 “The berries are poisonous, so this was quite interesting. I was like ‘mistletoe?’ (laughs) Gosh, ok.” Participant K. A3 “A while back it was quite a popular thing for people to try … for their metastatic cancer. A lot of patients were looking at getting that in the private sector.” Oncologist A. |

| Barriers to recruitment | A4 “If it will help me then I’ll have it, but I find it hard to inject myself.” Participant G. A5 “Initially I said no ‘cos of all the extra hospital appointments … with the little one and we live out at (village X) so getting to the hospital (is difficult).” Participant B. |

| Enablers to recruitment | A6 “I thought it was a chance to maintain my family life by reducing my side effects.” Participant H. A7 “Having a natural product that could alleviate something like a chemo treatment, I found the idea of that absolutely amazing.” Participant J. A8 “I said ‘yes I’d like to go ahead with it’ because I did see that Germany, Switzerland and Holland had already started using it and I did a bit of research and people were paying for it privately in America and this country …. I just thought anything that will give me an edge as well is absolutely going to help. Help me and also other people for the future, so it’s win-win.” Participant J. A9 “If I am finding this too much, I can say no… the other things I didn’t have control over.” Participant C. A10 “[Patients] question if there is any trial they would be eligible for, having mistletoe, because I think they in a way are aware …. The thing is patients are interested; I find them to be more interested.” Research Nurse A. A11 “[Patients were] clearly enthusiastic about potentially entering the study …. Happy to do any extra attendances that might be necessary.” Oncologist A. |

| B Retention and adherence | |

| Barriers to retention and adherence | B1 “When you don’t like needles then you’ll always be terrified by needles.” Participant H. B2 “You have to build the injection up yourself … in some ways I found that quite difficult because you’ve got time to think about what you’re doing and I’d rather not, I’d rather just take something out of a packet and off. Yeah. So in a way it prolonged the agony.” Participant J. B3 “I kind of feel like if someone notices that she’s not reacting then she probably will think she’s on placebo and may drop off. So far it didn’t happen but I can’t really say it’s not going to.” Research Nurse A. B4 “It’s proven to be a bit tiresome, I must be honest with you, having to come into oncology … we have to keep going back weekly and it means coming into the city and it’s a nightmare to park and all of those things.” Participant D. B5 “Well I have to say I didn’t like going [to the hospital]… it did make it more stressful because obviously the place you don’t want to go to is the place you’ve got to go to, but they temperature checked you at the door on the way in, I had a mask, I had gloves, they had masks and you just had to get on with it really.” Participant F. B6 “I had the first week of radio and then ... I kept forgetting to take it.” Participant A. B7 “Once I’d finished the other treatment then the mistletoe became kind of secondary …. After my last radiotherapy I rang the bell and my husband and my daughter were there with me and that was a real kind of emotional moment and it felt like a real sense of closure and yet with the mistletoe, that was still going on, so it wasn’t a closure.” Participant E. |

| Enablers to retention and adherence | B8 “It was painful and it was irritating me, I was like ‘oh I can’t be doing with this’ and I did have thoughts ‘oh shall I just finish with it?’ And then in the back of my mind I just thought ‘well would I really be having these reactions if I was on placebo? I just kind of had to ride the storm basically and I’m glad I did because I ended up sort of talking to myself going right, ok, there are positives to this, this is uncomfortable at the moment but, you know, it’s not going to last.’” Participant C. B9 “I had a blog page …. I told them all about the mistletoe on that and I got a very positive response.” Participant D. B10 “Even if they’d said they got a skin reaction and we’d said ‘ok, tell us about that, is that problematic’, they were still really keen to kind of carry on and say ‘no, I really want to do this and it’s fine’ …. So once they’d signed up to it they really wanted to persevere and see it through.” Research Nurse C. B11 “I’ve got an alarm on my phone that goes off in the morning, I’ve chosen Justin Bieber’s classic hit ‘Mistletoe’ to remind me!” Participant E. B12 “What we were concerned about is the injecting themselves. So they seem to be coping alright … and they all seem to be sort of happy to be carrying on with it which is actually more surprising.” Research Nurse B. B13 “To begin with I was a bit uncertain, but when I saw they were accepting it quite easily I thought that was quite good and they didn’t have any side effects. And none of them complained to me about being tired, whereas 99% of the people, if you look at any of my letters …. would have toxicity and fatigue.” Oncologist B. |

| C Assessment of blinding | C1 “What makes me think I might have had the placebo because I’ve had no skin reactions at all.” Participant F. C2 “I viewed [the skin reaction] as possibly having the actual mistletoe injection instead of a placebo so I was like this is good, I’ve actually got the mistletoe (laughs) so I was quite pleased ... I think with the reaction that I had and the way that I felt throughout chemotherapy, I would lean more towards thinking that I had had either mistletoes, but like I say you never know, maybe it was all in my mind. But I think, yeah, I think that I did have mistletoe.” Participant B. C3 “I feel very strongly that it was the mistletoe …. I was ready for the [chemotherapy] side effects and I didn’t have them … All I had was hunger.” Participant K. C4 “I don’t know if it was the mistletoe that sort of helped or if it was just the frame of mind, I honestly couldn’t tell you.” Participant A. C5 “Some people were saying I don’t think I had it because I still had some side effects or there were others that said I think I did have it because I felt great all the way through, but I think they definitely had an opinion as to whether they were on it.” Research Nurse C. C6 “So the colour of the [mistletoe] liquid is probably a light yellow but the saline is … colourless.… I can say from week four I can see the difference.” Research Nurse A. |

| D Adverse events | Relevant quotes in B and C, e.g., B8, B9, and C2 |

| E Questionnaire data | E1 “There was some slightly odder questions than others. There was a couple of questions about my sex life which I thought was interesting, a bit left-field.” Participant E. E2 “... there were questions about kind of, you know, like your sex life and that sort of… Some of that obviously, yeah, ... I just put not applicable.” Participant C. |

| F Complementary and alternative medicine beliefs | F1 “I fully understand the power of plants ... But I don’t fully believe they can cure everything ‘cos I think there is a place for engineered drugs if you need them. I think it’s a complementary thing.” Participant F. F2 “To be perfectly honest I don’t really think about it … just go with the flow.” Participant A, who had not used CAM therapies previously. F3 “I think mainstream treatment should absolutely sit alongside kind of complementary or additional therapies because if it’s improving their general health, wellbeing, emotional and physical kind of health then that’s great.” Research Nurse C. F4 “I tend to be fairly relaxed about patients taking …. complementary medicines because I think at the very least you’ll be harnessing a placebo and potential psychological benefits, and then there may be added benefits. Now if it’s got a very active ingredient or there’s something unknown about it then I’d be more cautious ‘cos I think we just don’t have any evidence about the interactions.” Oncologist A. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duncan, L.J.; Bryant, S.; Feder, G.; Gresham, M.; Gibson, P.; Sharp, D.; Braybrooke, J.P.; Huntley, A.L. The Mistletoe and Breast Cancer (MAB) Study: A UK Mixed-Phase, Pilot, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Cancers 2025, 17, 3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193169

Duncan LJ, Bryant S, Feder G, Gresham M, Gibson P, Sharp D, Braybrooke JP, Huntley AL. The Mistletoe and Breast Cancer (MAB) Study: A UK Mixed-Phase, Pilot, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193169

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuncan, Lorna J., Susan Bryant, Gene Feder, Maria Gresham, Poppy Gibson, Debbie Sharp, Jeremy P. Braybrooke, and Alyson L. Huntley. 2025. "The Mistletoe and Breast Cancer (MAB) Study: A UK Mixed-Phase, Pilot, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193169

APA StyleDuncan, L. J., Bryant, S., Feder, G., Gresham, M., Gibson, P., Sharp, D., Braybrooke, J. P., & Huntley, A. L. (2025). The Mistletoe and Breast Cancer (MAB) Study: A UK Mixed-Phase, Pilot, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Cancers, 17(19), 3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193169