The Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors: The Role of Social Factors

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

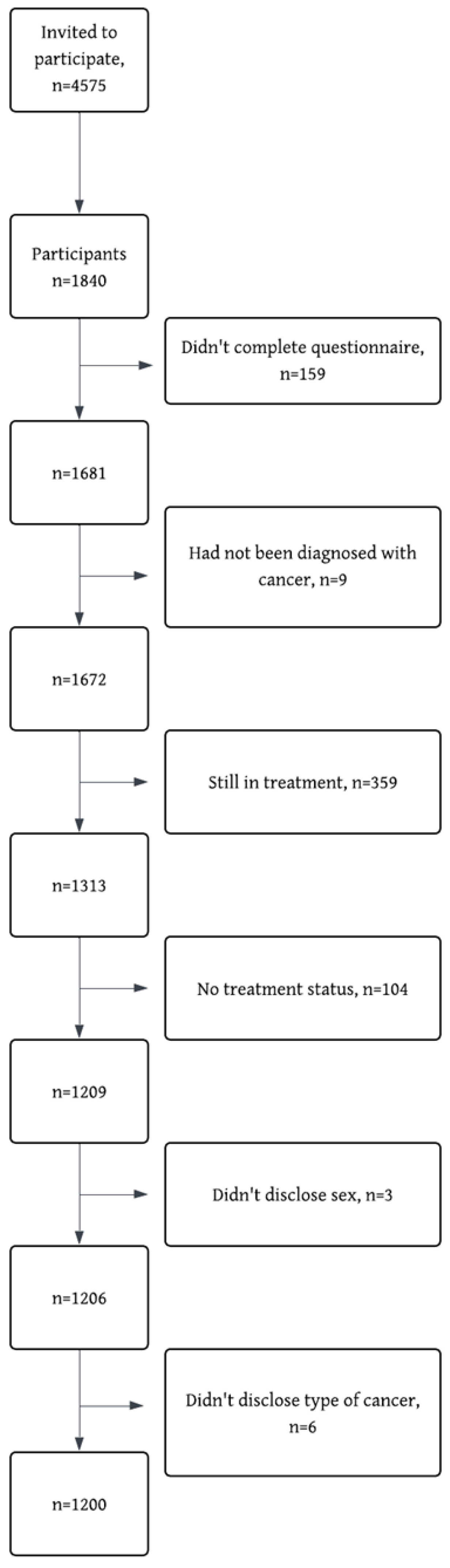

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Demographic Characteristics

2.2.2. EORTC-QLQ-C30

2.2.3. PHQ-9

2.2.4. The Compass

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Inferential Statistics

3.2.1. All Survivors

3.2.2. Gender Differences

3.2.3. Cancer Type

4. Discussion

4.1. Gender Differences

4.2. Cancer Specific Predictors

4.3. Importance of Social Variables

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jemal, A.; Sung, H.; Kelly, K.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. The Cancer Atlas [Internet]. American Cancer Society & the International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2025, p. 76. Available online: https://canceratlas.cancer.org/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Sung, H.; Jiang, C.; Siegel, R.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Facts & Figures, 5th ed.; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Cancer [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Krabbameinsfélagið. Yfirlitstölfræði [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.krabb.is/krabbamein/tolfraedi/krabbamein-og-gaedaskraning/heildartolfraedi-meina (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Parry, C.; Kent, E.E.; Mariotto, A.B.; Alfano, C.M.; Rowland, J.H. Cancer survivors: A booming population. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2011, 20, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonorezos, E.; Devasia, T.; Mariotto, A.B.; Mollica, M.A.; Gallicchio, L.; Green, P.; Doose, M.; Brick, R.; Streck, B.; Reed, C.; et al. Prevalence of cancer survivors in the United States. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1784–1790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tu, H.; Wen, C.P.; Tsai, S.P.; Chow, W.-H.; Wen, C.; Ye, Y.; Zhao, H.; Tsai, M.K.; Huang, M.; Dinney, C.P.; et al. Cancer risk associated with chronic diseases and disease markers: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2018, 360, k134. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/360/bmj.k134 (accessed on 24 June 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebber, A.M.H.; Buffart, L.M.; Kleijn, G.; Riepma, I.C.; de Bree, R.; Leemans, C.R.; Becker, A.; Brug, J.; van Straten, A.; Cuijpers, P.; et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: A meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, W.; Vodermaier, A.; MacKenzie, R.; Greig, D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.R. Depression in cancer patients: Pathogenesis, implications and treatment (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2015, 9, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Li, J.-Q.; Shi, J.-F.; Que, J.-Y.; Liu, J.-J.; Lappin, J.M.; Leung, J.; Ravindran, A.V.; Chen, W.-Q.; Qiao, Y.-L.; et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gudina, A.T.; Cheruvu, V.K.; Gilmore, N.J.; Kleckner, A.S.; Arana-Chicas, E.; Kehoe, L.A.; Belcher, E.K.; Cupertino, A.P. Health related quality of life in adult cancer survivors: Importance of social and emotional support. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021, 74, 101996. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Late and Long-Term Effects of Cancer [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/survivorship/long-term-health-concerns/long-term-side-effects-of-cancer.html (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Lim, J.W.; Zebrack, B. Social networks and quality of life for long-term survivors of leukemia and lymphoma. Support. Care Cancer 2006, 14, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, C.H.; Kwan, M.L.; Neugut, A.I.; Ergas, I.J.; Wright, J.D.; Caan, B.J.; Hershman, D.; Kushi, L.H. Social networks, social support mechanisms, and quality of life after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 139, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, N.; Kelly, E.P.; Pawlik, T.M. Assessing structure and characteristics of social networks among cancer survivors: Impact on general health. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3045–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Duberstein, P.R. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2010, 75, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T.M.; Feinstein, A.R. A Critical Appraisal of the Quality of Quality-of-Life Measurements. JAMA 1994, 272, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosc, M. Assessment of social functioning in depression. Compr. Psychiatry 2000, 41, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamper, E.M.; Petersen, M.A.; Aaronson, N.; Costantini, A.; Giesinger, J.M.; Holzner, B.; Kemmler, G.; Oberguggenberger, A.; Singer, S.; Young, T.; et al. Development of an item bank for the EORTC Role Functioning Computer Adaptive Test (EORTC RF-CAT). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, J.; Gupta, N.; Kataki, A.; Roy, P.; Mehra, N.; Kumar, L.; Singh, A.; Malhotra, P.; Gupta, D.; Goyal, A.; et al. Health-related quality of life and its determinants among cancer patients: Evidence from 12,148 patients of Indian database. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2024, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geue, K.; Sender, A.; Schmidt, R.; Richter, D.; Hinz, A.; Schulte, T.; Brähler, E.; Stöbel-Richter, Y. Gender-specific quality of life after cancer in young adulthood: A comparison with the general population. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.; Wu, L.; Chen, K. Determinants of Quality of Life in Lung Cancer Patients. J. Nurs. Sch. 2018, 50, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biparva, A.J.; Raoofi, S.; Rafiei, S.; Kan, F.P.; Kazerooni, M.; Bagheribayati, F.; Masoumi, M.; Doustmehraban, M.; Sanaei, M.; Zarabi, F.; et al. Global quality of life in breast cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 13, e528–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguin, S.; Alves, I.G.; Camargo, H.T.F.; Pollo, C.F.; Segalla, A.V.Z.; de Oliveira, C. Comparative Study of the Quality of Life and Coping Strategies in Oncology Patients. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanski, J.; Jankowska-Polanska, B.; Rosinczuk, J.; Chabowski, M.; Szymanska-Chabowska, A. Quality of life of patients with lung cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalon, R.; Bachner, Y.G. Medical, social, and personal factors as correlates of quality of life among older cancer patients with permanent stoma. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 38, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagani, P.; Parpio, Y.; Gul, R.; Jabbar, A.A. Quality of life and its determinants in adult cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment in Pakistan. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 4, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, I.; Hombrados-Mendieta, I.; Melguizo-Garín, A.; Martos-Méndez, M.J. The Importance of Social Support, Optimism and Resilience on the Quality of Life of Cancer Patients. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 833176. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.833176/full (accessed on 17 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Laghousi, D.; Jafari, E.; Nikbakht, H.; Nasiri, B.; Shamshirgaran, M.; Aminisani, N. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among patients with colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019, 10, 453–461. Available online: https://jgo.amegroups.org/article/view/27616 (accessed on 4 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, Q. Gender Differences in Psychosocial Outcomes and Coping Strategies of Patients with Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepanov, D.; Palta, M.; Fryback, D.G.; Robert, S.A. Gender differences in health-related quality-of-life are partly explained by sociodemographic and socioeconomic variation between adult men and women in the US: Evidence from four US nationally representative data sets. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonhof, C.S.; de Rooij, B.H.; Schoormans, D.; Wasowicz, D.K.; Vreugdenhil, G.; Mols, F. Sex differences in health-related quality of life and psychological distress among colorectal cancer patients: A 2-year longitudinal study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinsen, A.K.G.; Kjaer, T.K.; Thygesen, L.C.; Maltesen, T.; Jakobsen, E.; Gögenur, I.; Borre, M.; Christiansen, P.; Zachariae, R.; Christensen, P.; et al. Social inequality in cancer survivorship: Educational differences in health-related quality of life among 27,857 cancer survivors in Denmark. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 20150–20162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osann, K.; Hsieh, S.; Nelson, E.L.; Monk, B.J.; Chase, D.; Cella, D.; Wenzel, L. Factors associated with poor quality of life among cervical cancer survivors: Implications for clinical care and clinical trials. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 135, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.M.; Bevilacqua, K.G.; Alpert, N.; Liu, B.; Dharmarajan, K.V.; Ornstein, K.A.; Taioli, E. Educational Attainment and Quality of Life among Older Adults before a Lung Cancer Diagnosis. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunanithi, G.; Sagar, R.P.; Joy, A.; Vedasoundaram, P. Assessment of Psychological Distress and its Effect on Quality of Life and Social Functioning in Cancer Patients. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2018, 24, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dehkordi, A.; Heydarnejad, M.S.; Fatehi, D. Quality of Life in Cancer Patients undergoing Chemotherapy. Oman Med. J. 2009, 24, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firkins, J.; Hansen, L.; Driessnack, M.; Dieckmann, N. Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarnejad, M.S.; Hassanpour, D.A.; Solati, D.K. Factors affecting quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Afr. Health Sci. 2011, 11, 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, M.; Hjermstad, M.J.; Tomaszewski, K.; Tomaszewska, I.; Hornslien, K.; Harle, A.; Arraras, J.; Morag, O.; Pompili, C.; Ioannidis, G.; et al. Gender effects on quality of life and symptom burden in patients with lung cancer: Results from a prospective, cross-cultural, multi-center study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 4253–4261. Available online: https://jtd.amegroups.org/article/view/43093 (accessed on 5 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pud, D. Gender differences in predicting quality of life in cancer patients with pain. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinquinato, I.; Marques da Silva, R.; Ticona Benavente, S.B.; Cristine Antonietti, C.; Siqueira Costa Calache, A.L. Gender differences in the perception of quality of life of patients with colorectal cancer. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2017, 35, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csuka, S.I.; Rohánszky, M.; Thege, B.K. Gender differences in the predictors of quality of life in patients with cancer: A cross sectional study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 68, 102492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrabadi, F.K.; Rahimzadeh, S. The Role of Gender in the Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors: Health Literacy and Cognitive Functioning. Int. J. Cancer Manag. 2024, 17, e149321. Available online: https://brieflands.com/articles/ijcm-149321#abstract (accessed on 5 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Duberstein, P.R. Depression and cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1797–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satin, J.R.; Linden, W.; Phillips, M.J. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer 2009, 115, 5349–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meléndez, J.C.; Mayordomo, T.; Sancho, P.; Tomás, J.M. Coping strategies: Gender differences and development throughout life span. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, T.; Forns, M.; Muñoz, D.; Pereda, N. Psychometric properties and dimensional structure of the Spanish version of the Coping Responses Inventory-Adult Form. Psicothema 2008, 20, 902–909. [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek, J.T.; Smith Ronald, E.; Zanas, J. Gender, Appraisal, and Coping: A Longitudinal Analysis. J. Pers. 1992, 60, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M.; Heck, G.L.V. Gender, coping and psychosomatic symptoms. Psychol. Med. 1990, 20, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, S.-C.J.; Huang, C.-H.; Chou, H.-C.; Wan, T.T.H. Gender Differences in Stress and Coping among Elderly Patients on Hemodialysis. Sex Roles 2009, 60, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamres, L.K.; Janicki, D.; Helgeson, V.S. Sex Differences in Coping Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review and an Examination of Relative Coping. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 6, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.J.; Rudolph, K.D. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 98–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powroznik, K.; Stepanikova, I.; Cook, K.S. Growth from Trauma: Gender Differences in the Experience of Cancer and Long-term Survivorship. In Gender, Women’s Health Care Concerns and Other Social Factors in Health and Health Care [Internet]; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2018; pp. 17–36. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/s0275-495920180000036001/full/html (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- van Roij, J.; Brom, L.; Youssef-El Soud, M.; van de Poll-Franse, L.; Raijmakers, N.J.H. Social consequences of advanced cancer in patients and their informal caregivers: A qualitative study. Support Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMasters, T.; Madhavan, S.; Sambamoorthi, U.; Kurian, S. A population-based study comparing HRQoL among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors to propensity score matched controls, by cancer type, and gender. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 2270–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, V.; Merx, H.; Stegmaier, C.; Ziegler, H.; Brenner, H. Quality of Life in Patients With Colorectal Cancer 1 Year After Diagnosis Compared With the General Population: A Population-Based Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4829–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graells-Sans, A.; Serral, G.; Puigpinós-Riera, R.; Grupo Cohort DAMA. Social inequalities in quality of life in a cohort of women diagnosed with breast cancer in Barcelona (DAMA Cohort). Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 54, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husson, O.; Zebrack, B.J.; Block, R.; Embry, L.; Aguilar, C.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Cole, S. Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescent and Young Adult Patients With Cancer: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Atreya, A.; Nepal, S.; Uddin, K.J.; Kaiser, R.; Menezes, R.G.; Lasrado, S.; Abdullah-Al-Noman, M. Assessment of quality of life (QOL) in cancer patients attending oncology unit of aTeaching Hospital in Bangladesh. Cancer Rep. 2023, 6, e1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loge, J.H.; Abrahamsen, A.F.; Ekeberg, Ø.; Kaasa, S. Reduced health-related quality of life among Hodgkin’s disease survivors: A comparative study with general population norms. Ann. Oncol. 1999, 10, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.-K.; Lu, C.-Y.; Yao, Y.; Chiang, C.-Y. Social functioning, depression, and quality of life among breast cancer patients: A path analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 62, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Fan, Y. Baseline functioning scales of EORTC QLQ-C30 predict overall survival in patients with gastrointestinal cancer: A meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2024, 33, 1455–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Morales, A.; Soto-Ruiz, N.; Agudelo-Suárez, A.A.; García-Vivar, C. Social determinants of health in post-treatment cancer survivors: Scoping review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 70, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hao, G.; Wu, M.; Hou, L. Social isolation in adults with cancer: An evolutionary concept analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 973640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R. The provision of social relationships. In Doing unto Others: Joining, Molding, Conforming, Helping, Loving; Rubin, Z., Ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer, N.K.; Elfering, A.; Jacobshagen, N.; Perrot, T.; Beehr, T.A.; Boos, N. The emotional meaning of instrumental social support. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2008, 15, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfadóttir, J.E.; Guðmundsdóttir, R.B.; Unnarsdóttir, A.B.; Þorvaldsdóttir, H.; Einarsdóttir, S.E.; Haraldsdóttir, Á.; Pálsson, G. Krabbameinsfélagið. Áttavitinn—Vísaðu Okkur Veginn: Rannsókn á Reynslu Fólks sem Greindist með Krabbamein á Árunum 2015–2019. 2024. Available online: https://www.krabb.is/media/attavitinn-fyrsti-hluti.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; De Haes, J.C.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Z.; Tang, Y.; Fu, J.; Doucette, J.; Murimi, I.B. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Breast Cancer: A Systematic review of EORTC QLQ-C30, FACT-B, and EORTC QLQ-BR23 Development and validation. Value Health 2019, 22, S530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankurtaran, E.S.; Ozalp, E.; Soygur, H.; Ozer, S.; Akbiyik, D.I.; Bottomley, A. Understanding the reliability and validity of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in Turkish cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 2008, 17, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osoba, D.; Aaronson, N.; Zee, B.; Sprangers, M.; te Velde, A. Modification of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 2.0) based on content validity and reliability testing in large samples of patients with cancer. The Study Group on Quality of Life of the EORTC and the Symptom Control and Quality of Life Committees of the NCI of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat Care Rehabil. 1997, 6, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fayers, P.M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Bjordal, K.; Groenvold, M.; Curran, D.; Bottomley, A. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual, 3rd ed.; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; Available online: https://qol.eortc.org/manual/scoring-manual/ (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Giesinger, J.M.; Loth, F.L.; Aaronson, N.K.; Arraras, J.I.; Caocci, G.; Efficace, F.; Groenvold, M.; van Leeuwen, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Ramage, J.; et al. Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 118, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coon, C.D.; Schlichting, M.; Zhang, X. Interpreting Within-Patient Changes on the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-LC13. Patient 2022, 15, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocks, K.; King, M.T.; Velikova, G.; Fayers, P.M.; Brown, J.M. Quality, interpretation and presentation of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30 data in randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 2008, 44, 1793–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajele, K.W.; Idemudia, E.S. Charting the course of depression care: A meta-analysis of reliability generalization of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ- 9) as the measure. Discov. Ment. Health 2025, 5, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kræftens Bekæmpelse. Barometerundersøgelsen [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.cancer.dk/om-os/det-arbejder-vi-for/barometerundersoegelsen/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Scott, N.W.; Fayers, P.M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Bottomley, A.; de Graeff, A.; Groenvold, M.; Gundy, C.; Koller, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Sprangers, M. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values [Internet]. EORTC Quality of Life Group. 2008. Available online: https://qol.eortc.org/manual/reference-values/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Ashing-Giwa, K.T.; Lim, J.W. Examining the Impact of Socioeconomic Status and Socioecologic Stress on Physical and Mental Health Quality of Life Among Breast Cancer Survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2009, 36, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingen, T.; Englich, B.; Estal-Muñoz, V.; Mareva, S.; Kassianos, A.P. Exploring the Relationship between Social Class and Quality of Life: The Mediating Role of Power and Status. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1983–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Role-Identity Salience, Purpose and Meaning in Life, and Well-Being among Volunteers. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2012, 75, 360–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnaghan, S.; Scruton, S.; Urquhart, R. Psychosocial interventions that target adult cancer survivors’ reintegration into daily life after active cancer treatment: A scoping review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 22, 607–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfadóttir, J.E.; Einarsdóttir, S.E.; Helgason, Á.R.; Þórisdóttir, B.; Guðmundsdóttir, R.B.; Unnarsdóttir, A.B.; Tryggvadóttir, L.; Birgisson, H.; Þorvaldsdóttir, G.H. Áttavitinn—Rannsókn á reynslu einstaklinga af greiningu og með ferð krabbameina á Íslandi árin 2015–2019. Læknablaðið 2022, 108, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Questions | Response Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional social support | “How much or little can you trust your close family, friends or acquaintances to discuss your disease or your well-being”, | 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = To some extent, 4 = For the most part, 5 = Fully |

| Instrumental social support | “How much or little can you trust your close family, friends or acquaintances…” - “To assist you with things such as chores and grocery shopping” - “To assist you with matters regarding your disease and treatment, i.e., to get to a doctor and assist with taking correct medication?”, - “To assist with legal matters?” | For each question: 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = To some extent, 4 = For the most part, 5 = Fully The summary score was a sum of scores for the three questions, 1–15 |

| Variables | Range | All Cancer Types | Breast Cancer | Prostate Cancer | Colorectal Cancer | All Other Cancer Types | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1200 | n = 391 (33%) | n = 167 (14%) | n = 147 (12%) | p a | n = 495 (41%) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Men | 485 (40.4) | 4 (1.0) | 167 (100) | 91 (61.9) | 223 (45.1) | ||

| Women | 715 (59.6) | 387 (99.0) | 0 (0.0) | 56 (38.1) | 272 (54.9) | ||

| Age, M (SD) | 23–85 | 62.0 (11.8) | 60.6 (10.7) | 69.1 (7.0) | 65.4 (9.3) | <0.001 | 59.8 (13.3) |

| Age at diagnosis, M (SD) | 18–80 | 58.9 (11.9) | 57.5 (10.5) | 65.9 (7.0) | 62.5 (9.1) | <0.001 | 56.6 (13.6) |

| Education, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Primary education | 211 (19.1) | 78 (21.3) | 14 (9.0) | 21 (15.9) | 98 (21.6) | ||

| Secondary school | 227 (20.5) | 89 (24.3) | 19 (12.3) | 34 (25.8) | 85 (18.7) | ||

| Trade school | 238 (21.5) | 46 (12.6) | 73 (47.1) | 26 (19.7) | 93 (20.5) | ||

| University degree | 431 (38.9) | 153 (41.8) | 49 (31.6) | 51 (38.6) | 178 (39.2) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.004 | ||||||

| Married or in a relationship | 934 (79.2) | 286 (74.7) | 143 (87.7) | 118 (81.4) | 387 (79.3) | ||

| Single | 183 (15.5) | 65 (17.0) | 16 (9.8) | 22 (15.2) | 80 (16.3) | ||

| Widowed | 62 (5.3) | 32 (8.4) | 4 (2.5) | 5 (3.4) | 21 (4.3) | ||

| Children under 18, n (%) | 0.005 | ||||||

| One or two children | 160 (13.5) | 55 (14.3) | 7 (4.2) | 14 (9.6) | 84 (17.1) | ||

| Three or more children | 47 (4.0) | 17 (4.5) | 5 (3.0) | 2 (1.4) | 23 (4.7) | ||

| Residence, n (%) | 0.534 | ||||||

| Capital area | 760 (64.1) | 239 (62.1) | 100 (60.6) | 100 (68.5) | 321 (65.5) | ||

| Urban area (<5.000) | 312 (26.3) | 104 (27.0) | 52 (31.5) | 35 (24.0) | 121 (24.7) | ||

| Urban area (>5.000) | 54 (4.6) | 18 (4.7) | 7 (4.2) | 6 (4.1) | 23 (4.7) | ||

| Rural area (<200) | 60 (5.1) | 24 (6.2) | 6 (3.6) | 5 (3.4) | 25 (5.1) | ||

| Personal income (ISK), n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0–300 thousand | 232 (21.7) | 94 (26.7) | 23 (14.7) | 21 (16.9) | 94 (21.4) | ||

| 301–500 thousand | 346 (32.3) | 131 (37.2) | 38 (24.4) | 35 (28.2) | 142 (32.3) | ||

| 501–700 thousand | 251 (23.4) | 78 (22.2) | 35 (22.4) | 27 (21.8) | 111 (25.3) | ||

| 701–1 million or more | 242 (22.6) | 49 (13.9) | 60 (38.5) | 41 (33.0) | 92 (21.0) | ||

| Working at diagnosis, n (%) | 817 (68.8) | 270 (70.1) | 108 (65.9) | 96 (65.3) | 0.412 | 343 (69.9) | |

| Number of treatment types, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| M (SD) | 2.06 (1.02) | 2.9 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.65 (0.8) | ||

| No treatment | 9 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 6 (1.2) | ||

| One treatment type | 425 (35.4) | 19 (4.9) | 101 (60.5) | 64 (43.5) | 241 (48.7) | ||

| Two treatment types | 384 (32.0) | 98 (25.1) | 47 (28.1) | 60 (40.8) | 179 (36.2) | ||

| Three or more treatment types | 382 (31.8) | 272 (69.5) | 19 (11.4) | 22 (15.0) | 69 (13.9) | ||

| Quality of life, M (SD) | |||||||

| EORTC Global Health Status/QoL | 0–100 | 72.3 (20.6) | 70.6 (20.4) | 77.0 (18.1) | 73.4 (20.5) | 0.006 | 71.8 (21.4) |

| Social variables, M (SD) | |||||||

| EORTC Role Functioning | 0–100 | 79.5 (27.3) | 76.6 (26.9) | 87.5 (21.7) | 78.5 (29.1) | <0.001 | 79.5 (28.2) |

| EORTC Social Functioning | 0–100 | 83.0 (24.8) | 81.8 (24.9) | 87.2 (21.8) | 82.6 (24.8) | 0.094 | 82.8 (25.6) |

| EORTC Financial Difficulties | 0–100 | 30.9 (32.8) | 34.3 (32.0) | 20.5 (28.9) | 30.0 (32.6) | <0.001 | 32.0 (34.1) |

| Emotional social support | 0–5 | 4.5 (0.9) | 4.4 (0.9) | 4.7 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.7) | 0.002 | 4.4 (0.9) |

| Instrumental social support | 0–15 | 12.8 (3.1) | 12.5 (3.2) | 13.5 (3.1) | 13.6 (2.3) | 0.063 | 12.7 (3.2) |

| PHQ-9 symptoms of depression, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Minimal | 758 (65.0) | 224 (59.1) | 128 (79.0 | 107 (73.8) | 298 (62.6) | ||

| Mild | 272 (23.4) | 100 (26.2) | 28 (17.3) | 28 (19.3) | 116 (24.4) | ||

| Moderate | 86 (7.4) | 32 (8.7) | 6 (3.7) | 6 (4.1) | 39 (8.2) | ||

| Moderately severe | 37 (3.2) | 19 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.1) | 16 (3.4) | ||

| Severe | 12 (1.0) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 7 (1.5) | ||

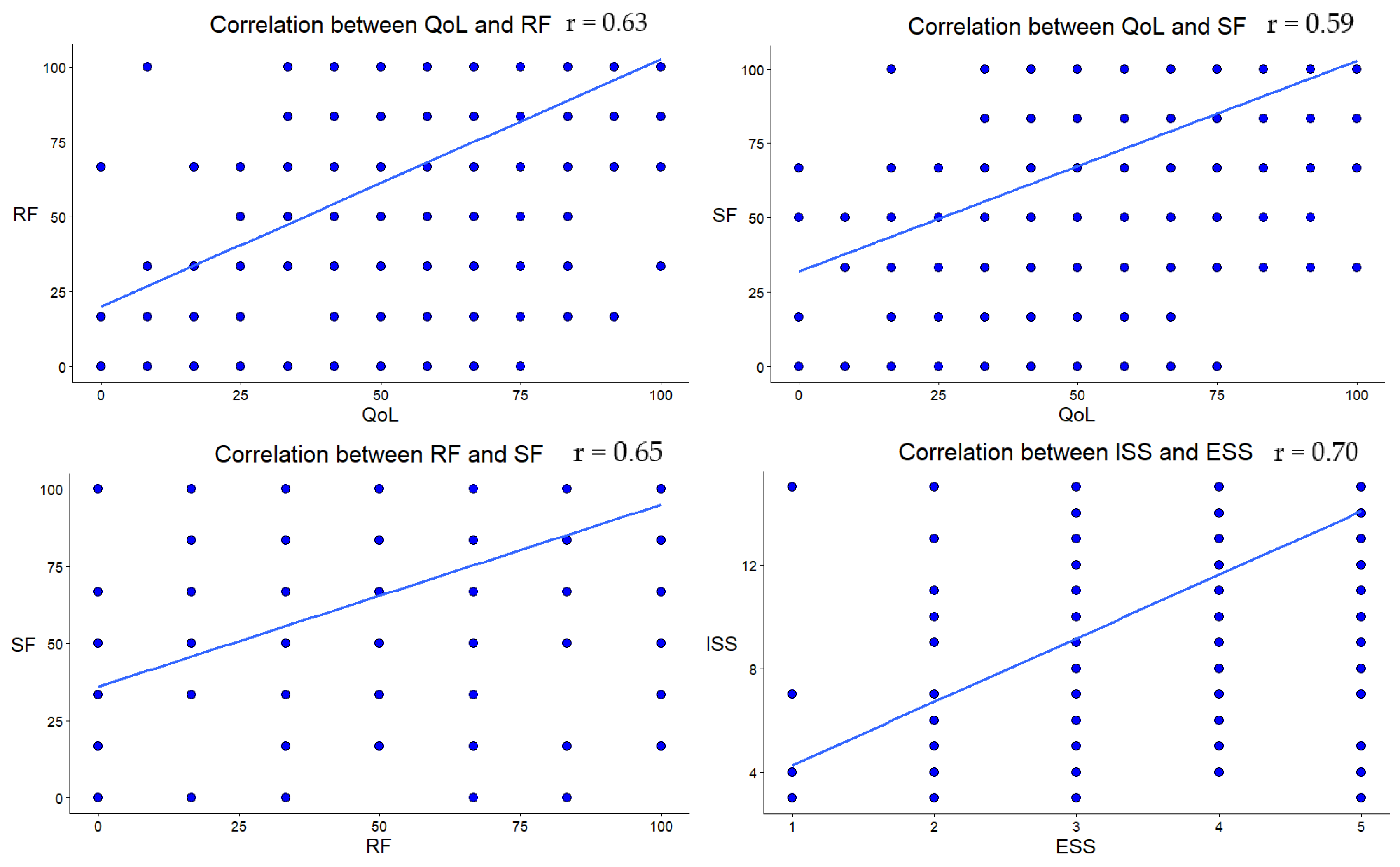

| Age | NrT | Edu | PI | W | FI | RF | SF | ISS | ESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | |||||||||

| - | ||||||||||

| NrT | −0.16 | |||||||||

| <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Edu | −0.15 | −0.00 | ||||||||

| <0.001 | 0.987 | |||||||||

| PI | −0.12 | −0.06 | 0.41 | |||||||

| <0.001 | 0.07 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| W | −0.42 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.40 | ||||||

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| FI | −0.19 | 0.23 | −0.07 | −0.16 | 0.06 | |||||

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.06 | ||||||

| RF | 0.02 | −0.16 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.10 | −0.37 | ||||

| 0.46 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| SF | 0.13 | −0.20 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.41 | 0.65 | |||

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.44 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| ISS | 0.12 | −0.11 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.28 | 0.17 | 0.23 | ||

| 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.33 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| ESS | 0.13 | −0.12 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.22 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.70 | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.21 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| QL | 0.09 | −0.14 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.09 | −0.36 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

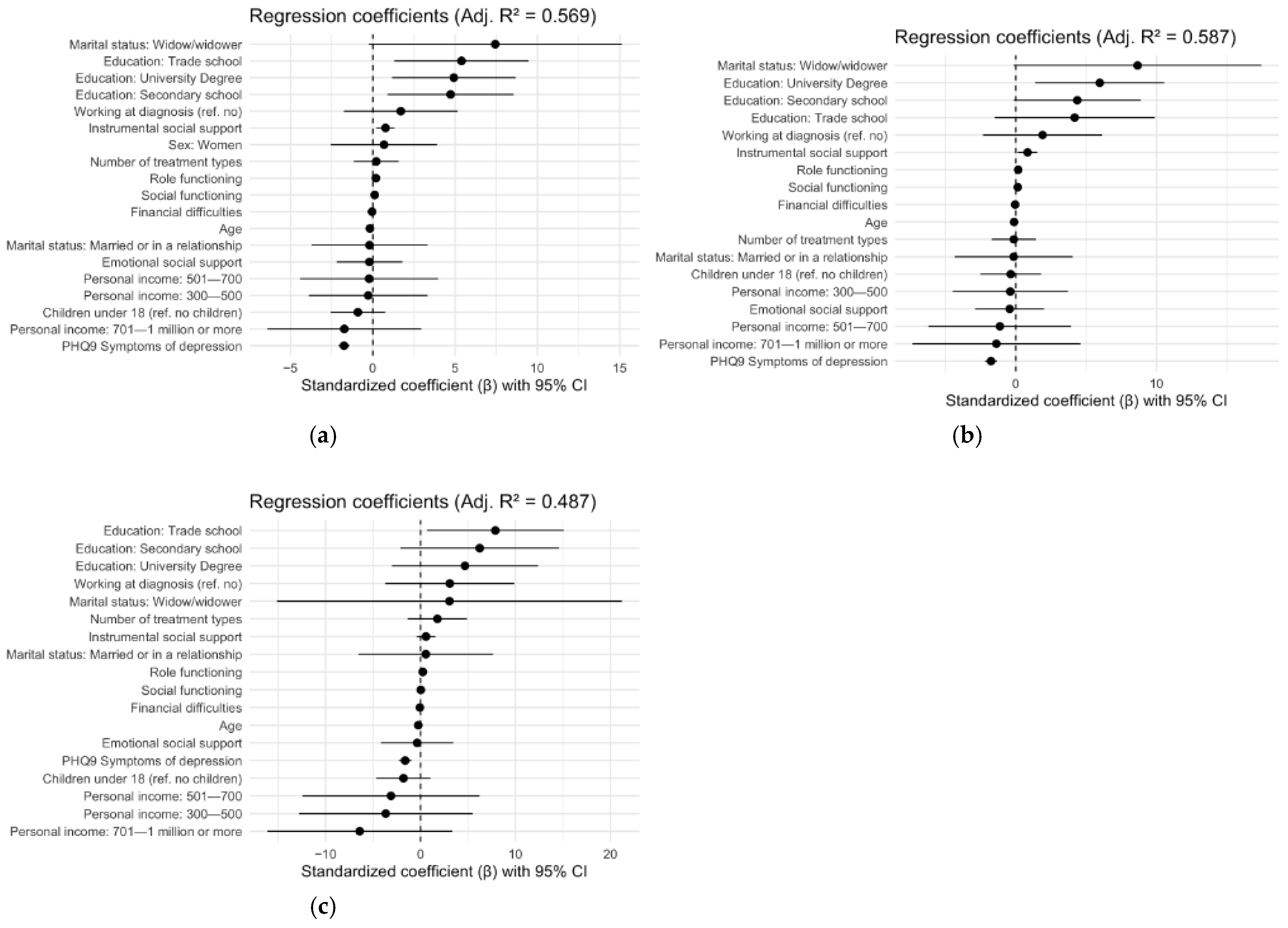

| All Survivors Adjusted R2: 0.57 | Women Adjusted R2: 0.59 | Men Adjusted R2: 0.49 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Df1 | Df2 | p | F | Df1 | Df2 | p | F | Df1 | Df2 | p | ||||

| 34.72 | 19 | 466 | <0.001 | 26.56 | 18 | 305 | <0.001 | 9.50 | 18 | 143 | <0.001 | ||||

| Predictor | β | B | SE | t | p | β | B | SE | t | p | β | B | SE | t | p |

| Intercept | 54.45 | 7.91 | 6.88 | <0.001 *** | 50.37 | 9.46 | 5.32 | <0.001 *** | 63.92 | 15.61 | 4.10 | <0.001 *** | |||

| Age | −0.11 | −0.18 | 0.07 | −2.54 | 0.01 * | −0.07 | −0.12 | 0.09 | −1.35 | 0.18 | −0.15 | −0.24 | 0.13 | −1.86 | 0.06 |

| Sex (ref. men) | |||||||||||||||

| Women | 0.03 | 0.68 | 1.65 | 0.41 | 0.68 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Education (ref. primary education) | |||||||||||||||

| Secondary school | 0.23 | 4.72 | 1.95 | 2.42 | 0.02 * | 0.21 | 4.37 | 2.29 | 1.91 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 6.23 | 4.24 | 1.47 | 0.14 |

| Trade school | 0.26 | 5.39 | 2.07 | 2.60 | 0.01 * | 0.20 | 4.18 | 2.89 | 1.45 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 7.88 | 3.65 | 2.16 | 0.02 * |

| University degree | 0.24 | 4.92 | 1.91 | 2.58 | 0.01 ** | 0.28 | 5.96 | 2.33 | 2.56 | 0.01 * | 0.25 | 4.68 | 3.89 | 1.20 | 0.23 |

| Marital status (ref. single) | |||||||||||||||

| Widow/widower | 0.36 | 7.44 | 3.92 | 1.90 | 0.06 | 0.41 | 8.65 | 4.47 | 1.94 | 0.053 | 0.16 | 3.05 | 9.20 | 0.33 | 0.74 |

| Married or in a relationship | −0.01 | −0.20 | 1.79 | −0.11 | 0.91 | −0.01 | −0.15 | 2.13 | −0.07 | 0.94 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 3.59 | 0.16 | 0.88 |

| Children under 18 (ref. no children) | −0.04 | −0.91 | 0.85 | −1.07 | 0.28 | −0.02 | −0.36 | 1.09 | −0.33 | 0.74 | −0.09 | −1.80 | 1.44 | −1.25 | 0.21 |

| Personal income (ref. 0–300 thousand) | |||||||||||||||

| 300–500 | −0.01 | −0.28 | 1.83 | −0.15 | 0.88 | −0.02 | −0.39 | 2.08 | −0.19 | 0.85 | −0.19 | −3.67 | 4.63 | −0.79 | 0.43 |

| 501–700 | −0.01 | −0.23 | 2.13 | −0.11 | 0.91 | −0.05 | −1.13 | 2.57 | −0.44 | 0.66 | −0.16 | −3.12 | 4.72 | −0.66 | 0.51 |

| 701–1 million or more | −0.08 | −1.73 | 2.38 | −0.73 | 0.47 | −0.07 | −1.38 | 3.03 | −0.45 | 0.65 | −0.34 | −6.41 | 4.93 | −1.30 | 0.20 |

| Working at diagnosis (ref. no) | 0.08 | 1.70 | 1.76 | 0.96 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 1.90 | 2.16 | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 3.08 | 3.44 | 0.90 | 0.37 |

| Number of treatments (ref. no treatment) | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.30 | 0.77 | −0.01 | −0.14 | 0.80 | −0.18 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 1.77 | 1.58 | 1.12 | 0.26 |

| EORTC Role Functioning | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 6.22 | <0.001 *** | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 4.66 | <0.001 *** | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 4.15 | <0.001 *** |

| EORTC Social Functioning | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 3.37 | <0.001 *** | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 3.61 | <0.001 *** | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.42 | 0.68 |

| EORTC Financial Difficulties | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −2.34 | 0.02 * | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.74 | 0.08 | −0.14 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −1.92 | 0.06 |

| Instrumental social support | 0.12 | 0.77 | 0.28 | 2.71 | 0.01 ** | 0.12 | 0.83 | 0.36 | 2.34 | 0.03 * | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 1.14 | 0.26 |

| Emotional social support | −0.01 | −0.21 | 1.01 | −0.20 | 0.84 | −0.02 | −0.43 | 1.24 | −0.35 | 0.79 | −0.02 | −0.36 | 1.92 | −0.19 | 0.85 |

| PHQ–9 symptoms of depression | −0.42 | −1.75 | 0.17 | −10.32 | <0.001 *** | −0.41 | −1.76 | 0.21 | −8.51 | <0.001 *** | −0.39 | −1.62 | 0.33 | −4.89 | <0.001 *** |

| Breast Cancer Adjusted R2: 0.57 | Prostate Cancer Adjusted R2: 0.48 | Colorectal Cancer Adjusted R2: 0.54 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Df1 | Df2 | p | F | Df1 | Df2 | p | F | Df1 | Df2 | p | ||||

| 14.60 | 19 | 176 | <0.001 | 6.38 | 17 | 84 | <0.001 | 6.47 | 18 | 67 | <0.001 | ||||

| Predictor | β | B | SE | t | p | β | B | SE | t | p | β | B | SE | t | p |

| Intercept | 52.55 | 16.65 | 3.16 | 0.001 ** | 42.72 | 23.40 | 1.83 | 0.07 | 54.07 | 24.46 | 2.21 | 0.03 * | |||

| Age | −0.14 | −0.26 | 0.13 | −1.96 | 0.052 | −0.03 | −0.08 | 0.30 | −0.28 | 0.78 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.87 | 0.39 |

| Sex (ref. men) | |||||||||||||||

| Women | 0.69 | 13.71 | 10.08 | 1.36 | 0.18 | - | - | - | - | 0.31 | 5.54 | 3.35 | 1.65 | 0.10 | |

| Education (ref. primary education) | |||||||||||||||

| Secondary school | 0.50 | 9.87 | 2.98 | 3.31 | 0.001 ** | 0.44 | 7.42 | 6.72 | 1.10 | 0.27 | −0.22 | −3.92 | 4.89 | −0.80 | 0.43 |

| Trade school | 0.46 | 9.15 | 3.59 | 2.54 | 0.012 * | 0.17 | 2.91 | 5.82 | 0.50 | 0.62 | −0.22 | −3.94 | 5.34 | −0.74 | 0.46 |

| University degree | 0.41 | 8.15 | 3.02 | 2.70 | 0.008 ** | 0.40 | 6.82 | 6.36 | 1.07 | 0.29 | −0.08 | −1.38 | 4.77 | −0.29 | 0.77 |

| Marital status (ref. single) | |||||||||||||||

| Widow/widower | 0.27 | 5.43 | 5.08 | 1.07 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 4.99 | 9.17 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 1.12 | 13.64 | 0.08 | 0.93 |

| Married or in a relationship | −0.03 | −0.52 | 2.91 | −0.18 | 0.86 | 0.10 | 1.72 | 4.63 | 0.37 | 0.71 | −0.19 | −3.41 | 3.93 | −0.87 | 0.39 |

| Children under 18 (ref. no children) | −0.03 | −0.58 | 1.43 | −0.41 | 0.69 | −0.04 | −1.02 | 2.26 | −0.45 | 0.65 | −0.06 | −1.66 | 2.50 | −0.66 | 0.51 |

| Personal income (ref. 0–300 thousand) | |||||||||||||||

| 300–500 | 0.19 | 3.71 | 2.73 | 1.36 | 0.17 | −0.50 | −8.46 | 5.01 | −1.69 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 3.78 | 5.28 | 0.72 | 0.48 |

| 501–700 | 0.10 | 2.02 | 3.31 | 0.61 | 0.54 | −0.18 | −3.03 | 5.22 | −0.58 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 11.24 | 5.51 | 2.04 | 0.045 * |

| 701–1 million or more | −0.04 | −0.85 | 3.82 | −0.22 | 0.82 | −0.35 | −5.96 | 5.09 | −1.17 | 0.24 | 0.55 | 9.72 | 5.91 | 1.64 | 0.10 |

| Working at diagnosis (ref. no) | −0.05 | −1.08 | 2.93 | −0.37 | 0.71 | 0.12 | 2.09 | 3.53 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 5.98 | 4.18 | 1.43 | 0.16 |

| Number of treatments (ref. no treatment) | −0.10 | −2.30 | 1.24 | −1.85 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 1.85 | 0.26 | 0.80 | −0.05 | 1.14 | 2.04 | −0.56 | 0.58 |

| EORTC Role Functioning | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 4.38 | <0.001 *** | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 4.50 | <0.001 *** | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 4.36 | <0.001 *** |

| EORTC Social Functioning | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.80 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.75 |

| EORTC Financial Difficulties | −0.10 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −1.88 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.41 | 0.69 | −0.11 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.12 | 0.27 |

| Instrumental social support | 0.10 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 1.25 | 0.21 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Emotional social support | 0.001 | 0.03 | 1.59 | 0.16 | 0.99 | −0.01 | −0.30 | 1.93 | −0.15 | 0.88 | −0.12 | −3.59 | 2.45 | −1.47 | 0.15 |

| PHQ-9 symptoms of depression | −0.41 | −1.74 | 0.28 | −6.32 | <0.001 *** | −0.37 | −2.21 | 0.60 | −3.71 | <0.001 *** | −0.23 | −1.12 | 0.55 | −2.03 | 0.046 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alfonsdóttir, S.Á.; Hjördísar Jónsdóttir, H.L.; Þorvaldsdóttir, G.H.; Einarsdóttir, S.E.; Torfadóttir, J.E.; Gunnarsdóttir, S. The Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors: The Role of Social Factors. Cancers 2025, 17, 3145. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193145

Alfonsdóttir SÁ, Hjördísar Jónsdóttir HL, Þorvaldsdóttir GH, Einarsdóttir SE, Torfadóttir JE, Gunnarsdóttir S. The Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors: The Role of Social Factors. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3145. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193145

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlfonsdóttir, Sigríður Ása, Harpa Lind Hjördísar Jónsdóttir, Guðfinna Halla Þorvaldsdóttir, Sigrún Elva Einarsdóttir, Jóhanna Eyrún Torfadóttir, and Sigríður Gunnarsdóttir. 2025. "The Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors: The Role of Social Factors" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3145. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193145

APA StyleAlfonsdóttir, S. Á., Hjördísar Jónsdóttir, H. L., Þorvaldsdóttir, G. H., Einarsdóttir, S. E., Torfadóttir, J. E., & Gunnarsdóttir, S. (2025). The Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors: The Role of Social Factors. Cancers, 17(19), 3145. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193145