Patients Who Refuse Blood Transfusions Should Not Be Discouraged from Immediate Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy: A Retrospective Study on Severe Bleeding Risks

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

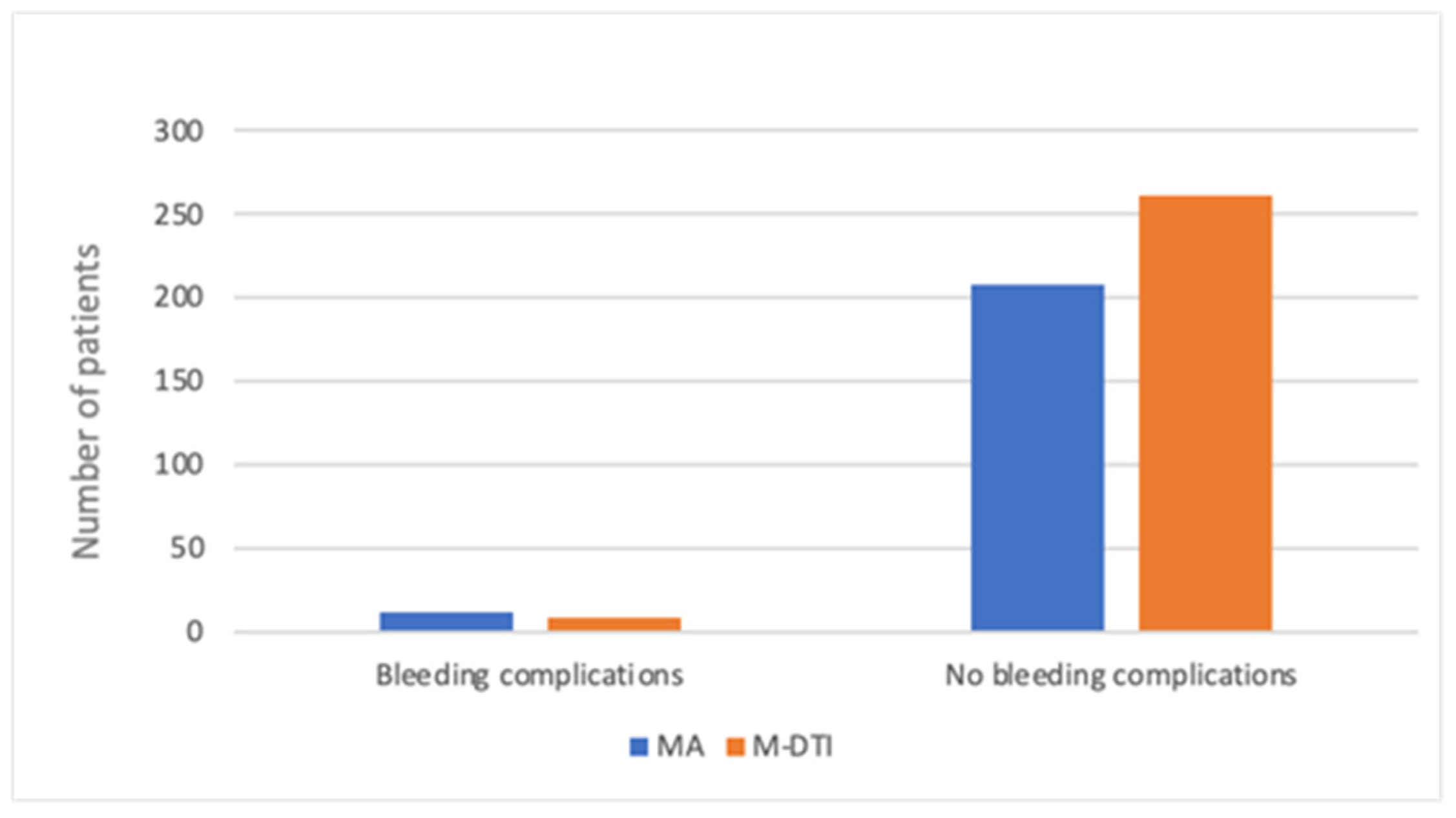

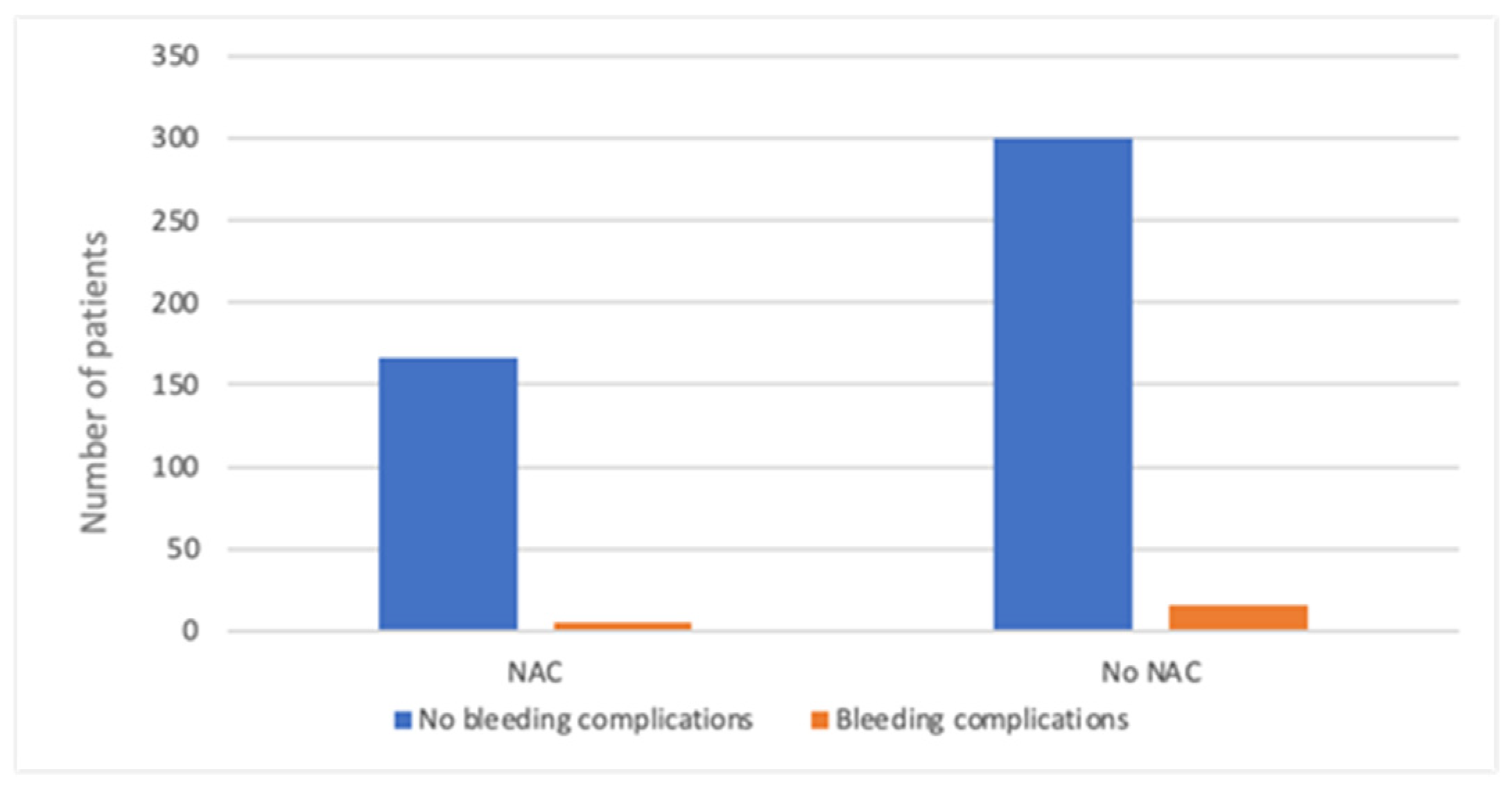

3. Results

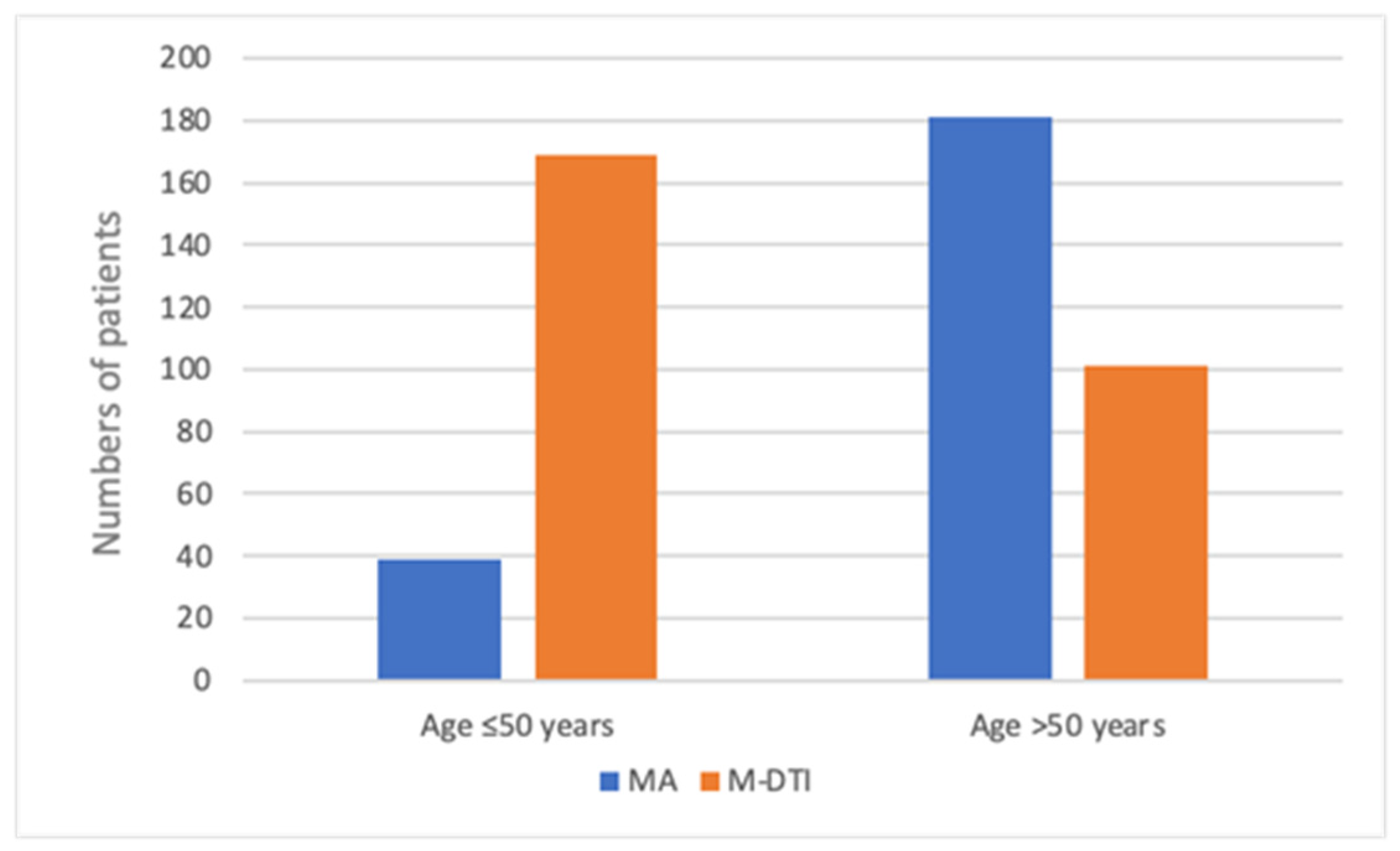

3.1. Age

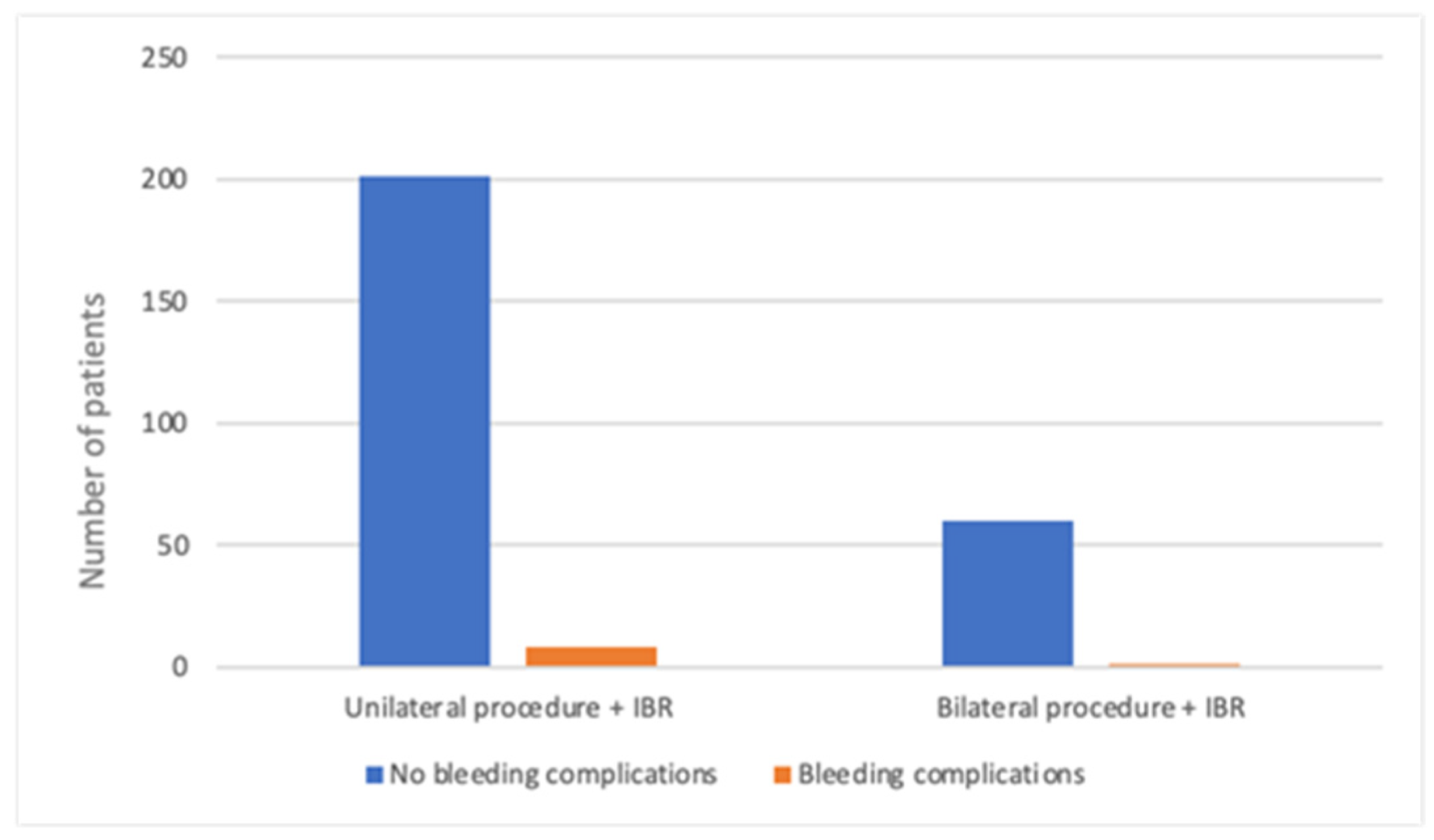

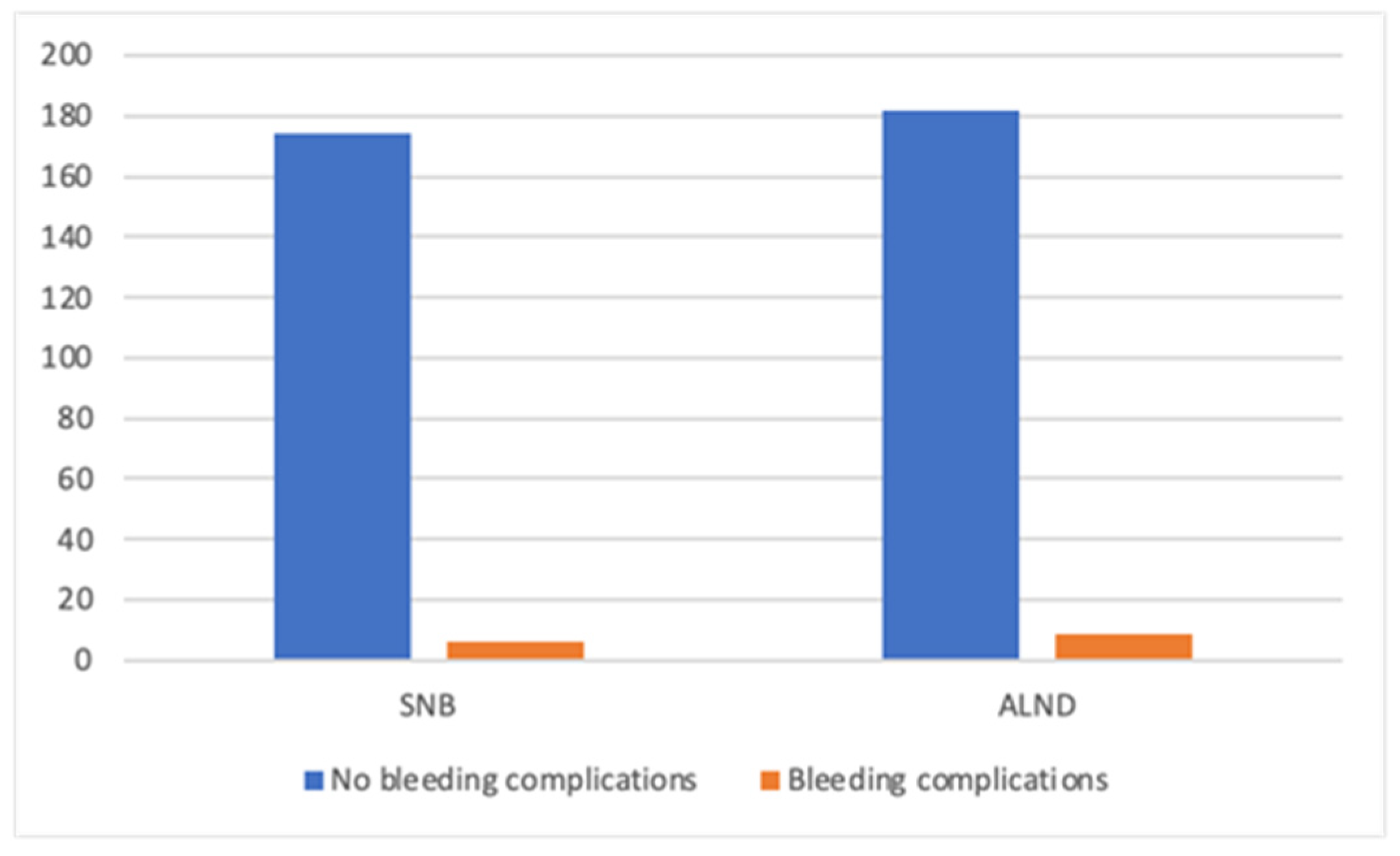

3.2. Diagnosis and Type of Procedure

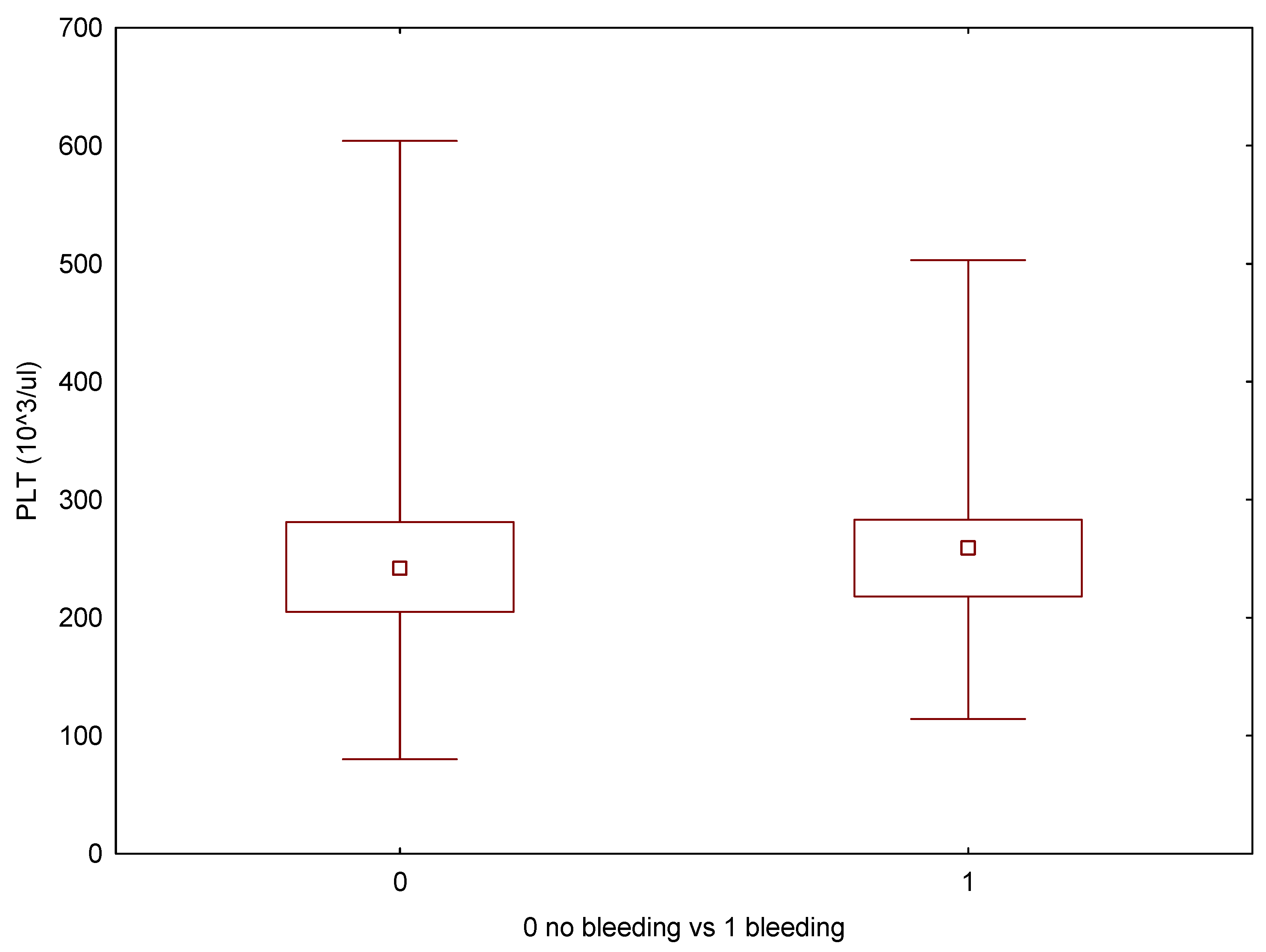

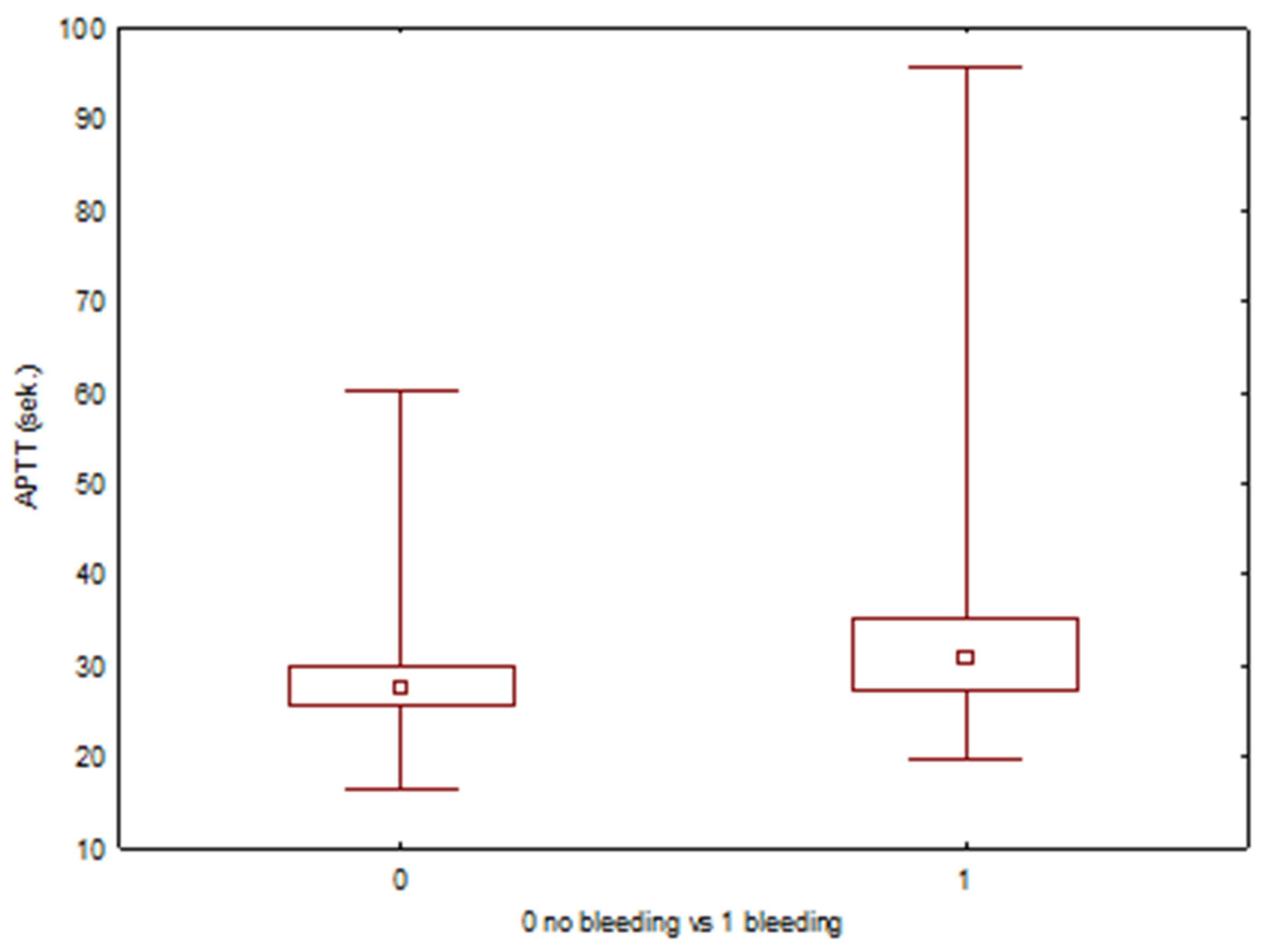

3.3. Patient-Related Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| M-DTI | Mastectomy with direct-to-implant reconstruction |

| MA | Mastectomy alone |

| JW | Jehovah’s Witnesses |

| BCS | Breast Conserving Surgery |

| IBR | Immediate Breast Reconstruction |

| RRM | Risk Reducing Mastectomy |

| SNB | Sentinel Node Biopsy |

| ALND | Axillary Lymph Nodes Dissection |

| NAC | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy |

| PLT | Platelets |

| APTT | Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CIs | Confidence intervals |

| LMWH | Low molecular weight heparin |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| BCSR | Breast Cancer Surgery Risk |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, U.; Barańska, K.; Miklewska, M.; Didkowska, J.A. Cancer incidence and mortality in Poland in 2020. Nowotwory J. Oncol. 2023, 73, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, B.M.; Rodrigues, I.M.; Marquez, L.V.; Pires, U.D.S.; de Oliveira, S.V. The impact of mastectomy on body image and sexuality in women with breast cancer: A systematic review. Psicooncología 2021, 18, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, M.; Kufel-Grabowska, J.; Bartoszkiewicz, M.; Ramlau, R.; Łukaszuk, K. Sexual well being of breast cancer patients. Nowotwory J. Oncol. 2021, 71, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słowik, A.; Jabłoński, M.; Michałowska-Kaczmarczyk, A.; Jach, R. Evaluation of quality of life in women with breast cancer, with particular emphasis on sexual satisfaction, future perspectives and body image, depending on the method of surgery. Psychiatr. Polska 2016, 51, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangkaew, C.; Somwangprasert, A.; Watcharachan, K.; Wongmaneerung, P.; Ko-Iam, W.; Kaweewan, I.; Ditsatham, C. Comparison of Survival Outcomes of Breast-Conserving Surgery Plus Radiotherapy with Mastectomy in Early Breast Cancer Patients: Less Is More? Cancers 2025, 17, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.K.; Fairhurst, K.; Birkbeck, B.; Novintan, S.; Wilson, R.; Savović, J.; Holcombe, C.; Potter, S. Overall survival after mastectomy versus breast-conserving surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy for early-stage breast cancer: Meta-analysis. BJS Open 2024, 8, zrae040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi, S.; Londero, A.P.; Xholli, A.; Azioni, G.; Di Vora, R.; Paudice, M.; Bucimazza, I.; Cedolini, C.; Cagnacci, A. Risk-Reducing Breast and Gynecological Surgery for BRCA Mutation Carriers: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabrook, M.; Navas, A.S.; Rao, A. Meta-analysis and systematic review of long-term oncological safety of immediate breast reconstruction in patients with locally advanced breast cancer. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2025, 100, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Hofer, S.O.P.; McCready, D.R.; Jacks, L.M.; Cook, F.E.; Baxter, N. A Comparison of Surgical Complications Between Immediate Breast Reconstruction and Mastectomy: The Impact on Delivery of Chemotherapy—An Analysis of 391 Procedures. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltahir, Y.; Werners, L.L.C.H.; Dreise, M.M.; van Emmichoven, I.A.Z.; Jansen, L.; Werker, P.M.N.; de Bock, G.H. Quality-of-Life Outcomes between Mastectomy Alone and Breast Reconstruction: Comparison of patient-reported BREAST-Q and other health-related quality-of-life measures. Plastic Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 132, 201e–209e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Olarte, P.; Gil-Olarte, M.A.; Gómez-Molinero, R.; Guil, R. Psychosocial and sexual well-being in breast cancer survivors undergoing immediate breast reconstruction: The mediating role of breast satisfaction. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.H.; Scott, A.M.; Price, A.N.; Miller, H.C.; Klassen, A.F.; Jhanwar, S.M.; Mehrara, B.J.; Disa, J.J.; McCarthy, C.; Matros, E. Psychosocial and Sexual Well-Being Following Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Reconstruction. Breast J. 2016, 22, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagli, B.M.; Cogliandro, A.; Barone, M.; Persichetti, P.M. Quality-of-Life Outcomes between Mastectomy Alone and Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 133, 594e–595e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pačarić, S.; Orkić, Ž.; Babić, M.; Farčić, N.; Milostić-Srb, A.; Lovrić, R.; Barać, I.; Mikšić, Š.; Vujanić, J.; Turk, T.; et al. Impact of Immediate and Delayed Breast Reconstruction on Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, M.; Marie, B.; Dominique, R.; Caroline, A.; Marc-Karim, B.D.; Julien, M.; Sophie, L.; Anne-Déborah, B. Breast reconstruction and quality of life five years after cancer diagnosis: VICAN French National cohort. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 194, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gammal, M.M.; Lim, M.; Uppal, R.; Sainsbury, R. Improved immediate breast reconstruction as a result of oncoplastic multidisciplinary meeting. Breast Cancer: Targets Ther. 2017, 9, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hilli, Z.; Thomsen, K.M.; Habermann, E.B.; Jakub, J.W.; Boughey, J.C. Reoperation for Complications after Lumpectomy and Mastectomy for Breast Cancer from the 2012 National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP). Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilonzo, N.; Tsang, A.; Tsantes, S.; Estabrook, A.; Ma, A.M.T. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy: A ten-year analysis of trends and immediate postoperative outcomes. Breast 2017, 32, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, E.G.; Hamill, J.B.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Greco, R.J.; Qi, J.; Pusic, A.L. Complications in Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.; Sood, R.; Liu, D.; Calhoun, K.; Louie, O.; Neligan, P.; Said, H.; Mathes, D. Comparison of Outcomes in Immediate Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction Versus Mastectomy Alone. Plast. Surg. 2017, 26, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.; Hirsch, E.M.; Kim, J.Y.S.; Dumanian, G.A.; Mustoe, T.A.; Galiano, R.D.; Fine, N.A. Hematoma After Mastectomy With Immediate Reconstruction An Analysis of Risk Factors in 883 Patients. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2013, 71, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Kwon, H.-C.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.H.; Kwon, K.A.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, K.-Y.; Kim, H.-J. Bloodless cancer treatment results of patients who do not want blood transfusion: Single center experience of 77 cases. Support. Care Cancer 2009, 18, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garoufalia, Z.; Aggelis, A.; Antoniou, E.A.; Kouraklis, G.; Vagianos, C. Operating on Jehovah’s Witnesses: A Challenging Surgical Issue. J. Relig. Health 2021, 61, 2447–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łętowska Magdalena, R.A.; Szczeklika, I.; Piotr, G. (Eds.) Kraków: Medycyna Praktyczna; 2024. {Łętowska Magdalena, Rosiek Aleksandra, 2024}. Available online: https://www.mp.pl/interna/chapter/B16.IV.24.21 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- van de Grift, T.C.; Mureau, M.A.M.; Negenborn, V.N.; Dikmans, R.E.G.; Bouman, M.-B.; Mullender, M.G. Predictors of women’s sexual outcomes after implant-based breast reconstruction. PsychoOncology 2020, 29, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, C.; Bouche, C.; Weyl, A.; Ung, M.; Jouve, E.; Selmes, G.; Soule-Tholy, M.; Meresse, T.; Massabeau, C.; Cavillon, A.; et al. Is immediate breast reconstruction surgery safe for elderly women? Assessment of postoperative complications in women aged 70 years and older. Innov. Pract. Breast Health 2024, 2, e440–e449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcadet, J.; Bouche, C.; Arellano, C.; Gauroy, E.; Ung, M.; Jouve, E.; Selmes, G.; Soule-Tholy, M.; Meresse, T.; Massabeau, C.; et al. Is Immediate Breast Reconstruction an Option for Elderly Women? A Comparative Study Between Elderly and Younger Population. Clin. Breast Cancer 2025, 25, e440–e449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalji, S.Z.; Cortina, C.S.; Guo, M.S.; Kong, A.L. Postoperative Complications from Breast and Axillary Surgery. Surgi. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 103, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, O.; Rosado, N.; Sobti, N.; Vieira, B.L.; Liao, E.C. Meta-analysis of prepectoral implant-based breast reconstruction: Guide to patient selection and current outcomes. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 182, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonczyk, M.M.; Fisher, C.S.; Babbitt, R.; Paulus, J.K.; Freund, K.M.; Czerniecki, B.; Margenthaler, J.A.; Losken, A.; Chatterjee, A. Surgical Predictive Model for Breast Cancer Patients Assessing Acute Postoperative Complications: The Breast Cancer Surgery Risk Calculator. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 5121–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziwon, P.; Krzakowski, M.; Kalinka, E.; Zaucha, R.; Wysocki, P.; Kowalski, D.; Gryglewicz, J.; Wojtukiewicz, M.Z. Niedokrwistość u chorych na nowotwory—Zalecenia grupy ekspertów. Aktualizacja 2020 rok. Oncol. Clin. Pract. 2020, 6, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.S.; Agarwal, V.K. Rationalizing blood transfusion in elective breast cancer surgery: Analyzing justification and economy. Asian J. Transfus. Sci. 2020, 14, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissler, J.M.; Banuelos, J.; Jacobson, S.R.; Manrique, O.J.; Nguyen, M.-D.T.; Harless, C.A.; Tran, N.V.; Martinez-Jorge, J. Intravenous Tranexamic Acid in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction Safely Reduces Hematoma without Thromboembolic Events. Plast. Reconst. Surg. 2020, 146, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larcher, L.; Steinstraesser, L.; Campisi, C.; Riml, S.; Lazzeri, D.; Huemer, G.M. Pfannenstiel Scar and the Jehovahʼs Witness Patient: Should you perform a DIEP breast reconstruction? Plastic Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 131, 292e–293e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P.; Bekeny, J.C.; Zolper, E.G.; Verstraete, R.; Fan, K.L.; Evans, K.K. A single-center experience with head-to-toe microsurgical reconstruction in bloodless medicine patients. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2022, 75, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.E.; Tang, L.; Hasday, S.; Kwon, D.I.; Selby, R.R.; Kokot, N.C. Jehovah’s witness head and neck free flap reconstruction patient outcomes. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2023, 44, 103681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Meng, M.; Sa, R.; Yu, L.; Lu, Y.; Gao, B. Blood transfusion is correlated with elevated adult all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in the United States: NHANES 1999 to 2018 population-based matched propensity score study. Clinics 2024, 79, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Haider, K.; Sundaram, V.; Radosevic, J.; Burnouf, T.; Seghatchian, J.; Goubran, H. Red blood cell transfusion and outcome in cancer. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2017, 56, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z dnia 5 grudnia 1996, r. o zawodach lekarza i lekarza dentysty (Dz.U. z 1997 r., nr 28, poz. 152).

- Konwencja o prawach człowieka i biomedycynie (Przyjęta przez Komitet Ministrów w dniu 19 listopada 1996 roku). Available online: https://www.coe.int/t/dg3/healthbioethic/texts_and_documents/ets164polish.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Pacian, J. OŚWIADCZENIA ‘PRO FUTURO’—DYLEMATY PRAWN. Zesz. Prawnicze 2016, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocańda, K.; Siudak, Z.; Chrobot, M.; Witczak, B. Sensitive elements in the patient’s giving consent to a Health Service. Med Stud. 2024, 40, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska, Z.B. Statements for the event of incapacity to consent: Current issues and postulates regarding future law. Palliat. Med. Pract. 2023, 18, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różyńska, J.; Czarkowski, M. Emergency Research without Consent under Polish Law. Sci. Eng. Ethic 2007, 13, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mastectomy Alone—MA Group (n = 220) | Mastectomy with Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction—M-DTI Group (n = 270) | Total (n = 490) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 69 | 51.5 | 54 |

| Range | 28–92 | 24–76 | 24–92 |

| Age, years | |||

| ≤50 | 39 (17.7) | 169 (62.6) | 208 (42.4) |

| >50 | 181 (82.3) | 101 (37.4) | 282 (57.6) |

| Mastectomy type | |||

| Unilateral | 212 (96.4) | 209 (77.4) | 421 (85.9) |

| Bilateral | 8 (3.6) | 61 (22.6) | 69 (14.1) |

| Diagnosis (per breast) | n = 227 | n = 332 | n = 559 |

| Breast cancer | 217 (95.6) | 194 (58.4) | 411 (73.5) |

| T is/1/2 | 184 (81.1) | 187 (56.3) | 371 (66.4) |

| T 3/4 | 33 (14.5) | 6 (1.8) | 40 (7.2) |

| RRM | 7 (3.1) | 136 (41.0) | 143 (25.6) |

| Other | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (0.9) |

| Axillary surgery | |||

| None | 25 (11.0) | 149 (44.9) | 174 (31.1) |

| SNB | 75 (33.0) | 114 (34.3) | 189 (33.8) |

| ALND | 127 (56.0) | 69 (20.8) | 196 (35.1) |

| NAC | 89 (40.5) | 86 (31.9) | 175 (35.7) |

| Bleeding disorder | |||

| 25 (11.4) | 18 (6.7) | 43 (8.8) | |

| PLT < 150 × 109/L | 12 | 9 | 21 |

| INR > 1.2 | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| APTT > 36.9 | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Variable | OR | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 0.389 |

| M-DTI | 0.67 | 0.28 | 1.57 | 0.355 |

| Bilateral surgery | 0.96 | 0.28 | 3.34 | 0.951 |

| Bilateral surgery + IBR | 0.37 | 0.05 | 2.98 | 0.351 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.53 | 0.19 | 1.46 | 0.220 |

| ALND (vs SNB) | 1.60 | 0.57 | 4.50 | 0.371 |

| PLT [G/l] | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.882 |

| INR | 27.18 | 0.87 | 849.57 | 0.060 |

| APTT [s] | 1.14 | 1.05 | 1.24 | 0.001 |

| Variable | OR | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 0.989 |

| PLT [G/l] | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.849 |

| INR | 9.59 | 0.18 | 514.69 | 0.266 |

| APTT [s] | 1.10 | 1.01 | 1.20 | 0.033 |

| M-DTI | 0.83 | 0.22 | 3.18 | 0.786 |

| Bilateral surgery | 2.31 | 0.44 | 12.18 | 0.323 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.54 | 0.16 | 1.79 | 0.316 |

| ALND (vs SNB) | 1.66 | 0.53 | 5.22 | 0.386 |

| Min | Max | Average | Median | SD | Average—Bleeding Complications | Average—No Bleeding Complications | p (U-Mann–Whitney) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLT (103/μL) | 80 | 604 | 246 | 242,5 | 64.93 | 245 | 247 | 0.704 |

| INR | 0.92 | 2.01 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 0.079 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 0.200 |

| APTT (s) | 16.6 | 95.6 | 28.39 | 27.6 | 4.91 | 34.34 | 28.12 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skonieczna, M.; Strzałka, P.; Zadrożny, M.; Grabczak, W.; Pluta, P. Patients Who Refuse Blood Transfusions Should Not Be Discouraged from Immediate Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy: A Retrospective Study on Severe Bleeding Risks. Cancers 2025, 17, 3137. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193137

Skonieczna M, Strzałka P, Zadrożny M, Grabczak W, Pluta P. Patients Who Refuse Blood Transfusions Should Not Be Discouraged from Immediate Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy: A Retrospective Study on Severe Bleeding Risks. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3137. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193137

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkonieczna, Maria, Piotr Strzałka, Marek Zadrożny, Wojciech Grabczak, and Piotr Pluta. 2025. "Patients Who Refuse Blood Transfusions Should Not Be Discouraged from Immediate Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy: A Retrospective Study on Severe Bleeding Risks" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3137. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193137

APA StyleSkonieczna, M., Strzałka, P., Zadrożny, M., Grabczak, W., & Pluta, P. (2025). Patients Who Refuse Blood Transfusions Should Not Be Discouraged from Immediate Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy: A Retrospective Study on Severe Bleeding Risks. Cancers, 17(19), 3137. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193137