Clinical Outcome in Elderly Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated with Concomitant Cisplatin and Radiotherapy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- An increase of 30% of non-compliant elderly versus young patients with a statistical power of 87%. A percentage of non-compliant young patients equal to 10% was assumed.

- An increase of 25% mucositis grades > 2 in elderly versus young patients with a statistical power of 86%. A percentage of young patients with toxicity grade > 2 equal to 30% was assumed.

- An increase of 25% dysphagia grades > 2 in elderly versus young patients with statistical power of 85%. A percentage of young patients with toxicity grade > 2 equal to 35% was assumed.

- An increase of 25% dermatitis grades > 2 in elderly versus young patients with a statistical power of 87%. A percentage of young patients with toxicity grade > 2 equal to 25% was assumed.

2.2. Patients’ Characteristics and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Statement

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

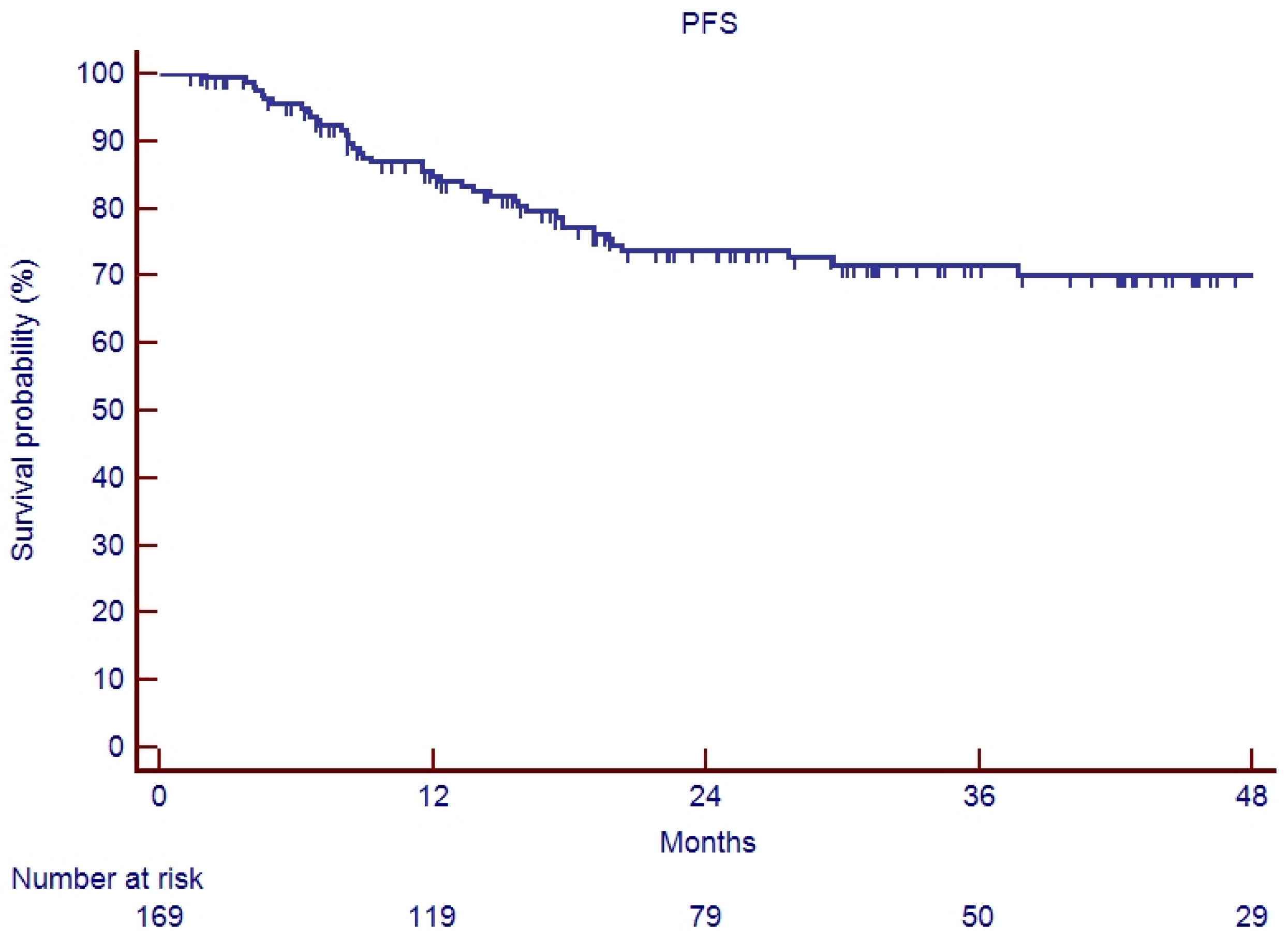

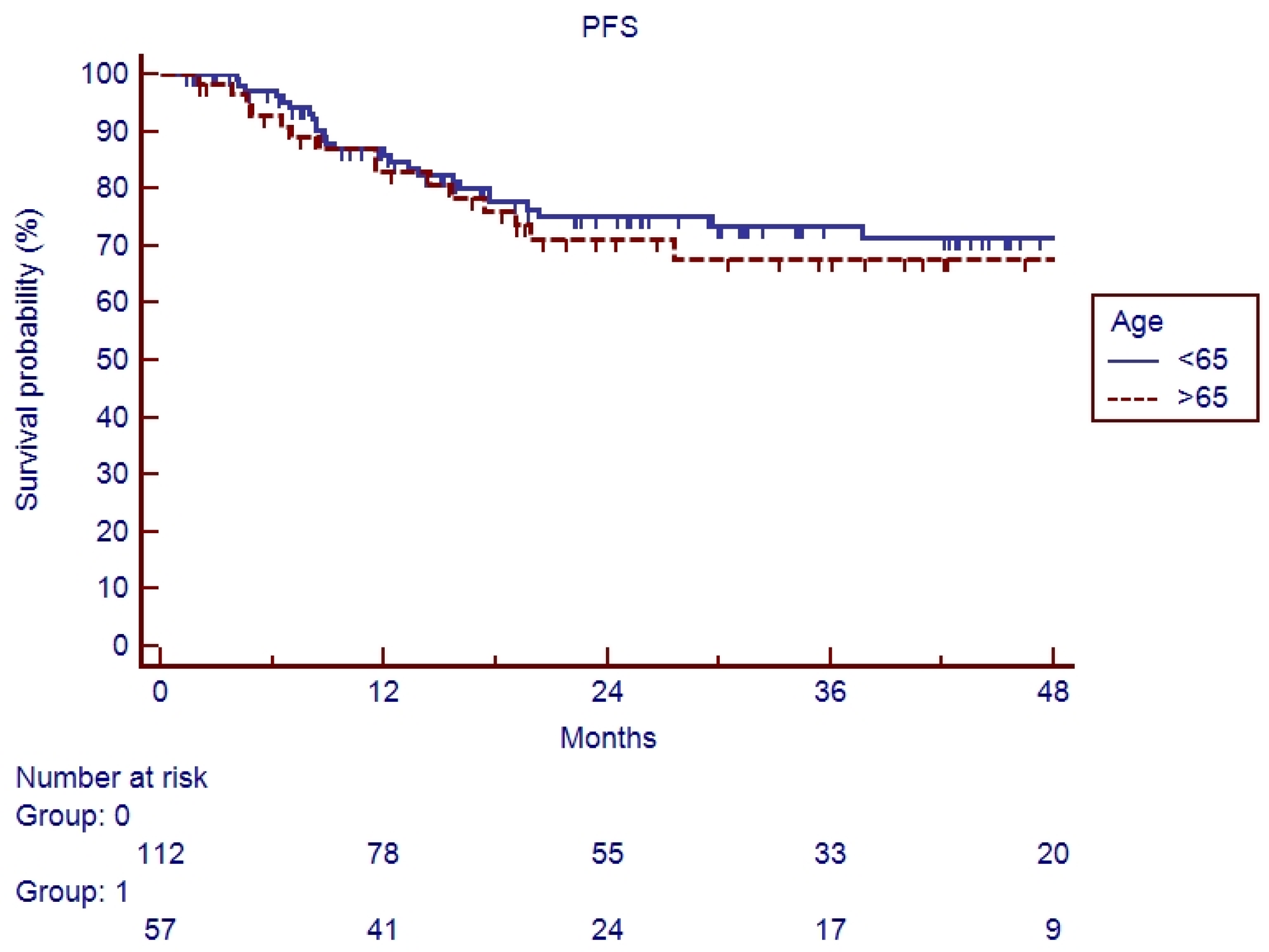

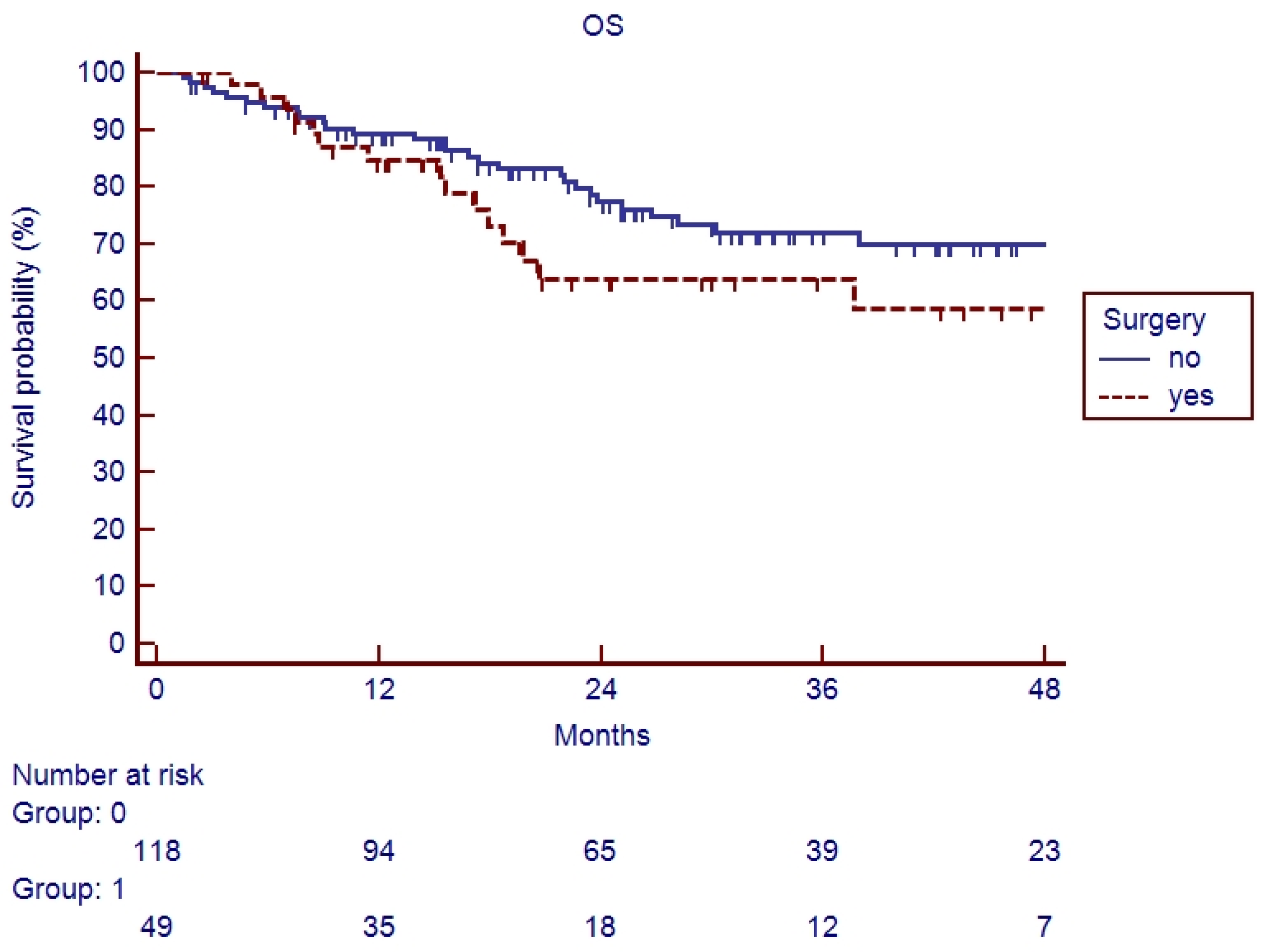

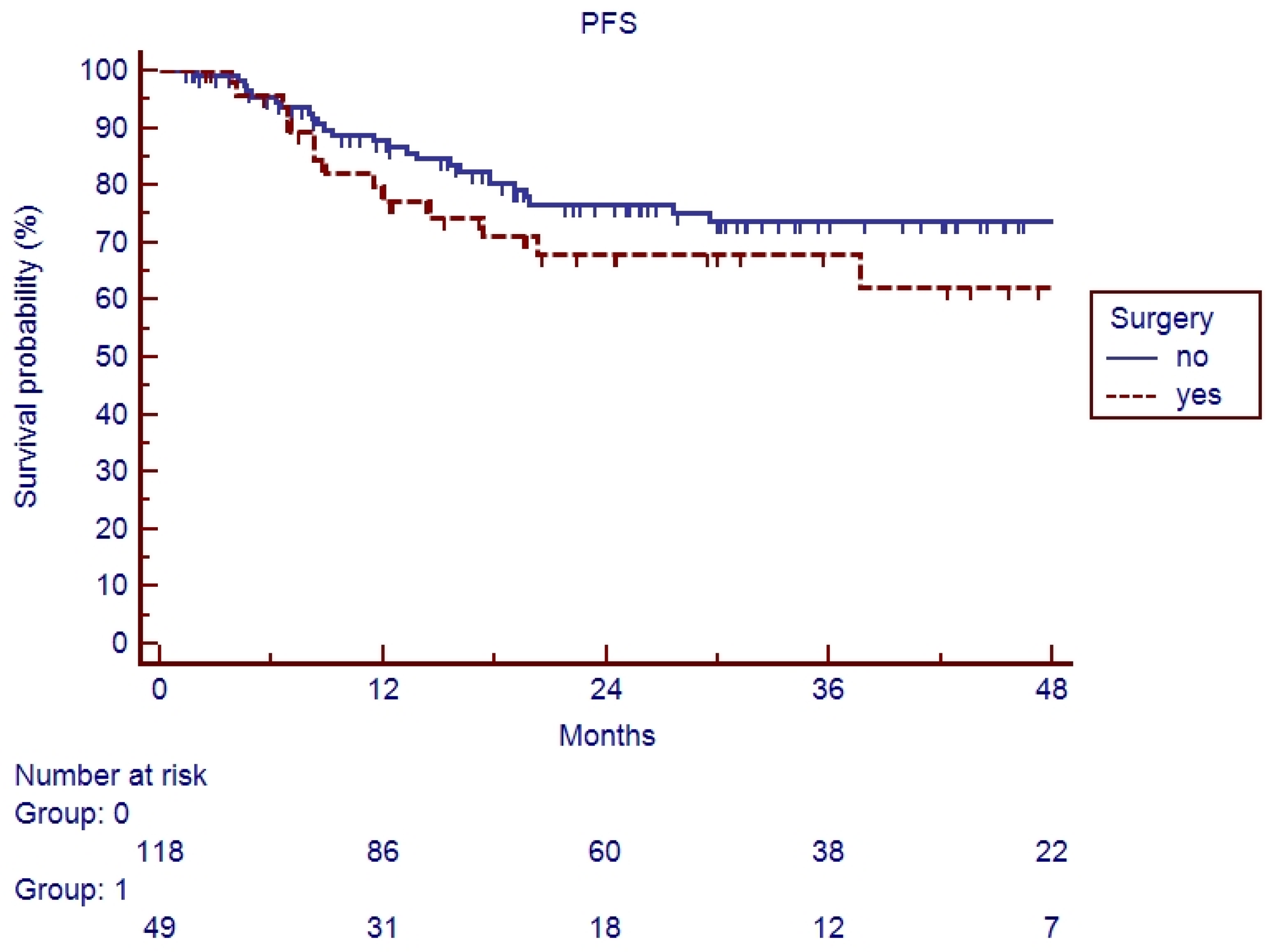

3.2. Survival Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Iqbal, M.S.; Dua, D.; Kelly, C.; Bossi, P. Managing older patients with head and neck cancer: The non-surgical curative approach. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2018, 9, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelstein, D.J.; Li, Y.; Adams, G.L.; Wagner, H., Jr.; Kish, J.A.; Ensley, J.F.; Schuller, D.E.; Forastiere, A.A. An Intergroup Phase III Comparison of Standard Radiation Therapy and Two Schedules of Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in Patients with Unresectable Squamous Cell Head and Neck Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernier, J.; Domenge, C.; Ozsahin, M.; Matuszewska, K.; Lefèbvre, J.L.; Greiner, R.H.; Giralt, J.; Maingon, P.; Rolland, F.; Bolla, M.; et al. Postoperative Irradiation with or without Concomitant Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.S.; Pajak, T.F.; Forastiere, A.A.; Jacobs, J.; Campbell, B.H.; Saxman, S.B.; Kish, J.A.; Kim, H.E.; Cmelak, A.J.; Rotman, M.; et al. Postoperative Concurrent Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy for High-Risk Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonner, J.A.; Harari, P.M.; Giralt, J.; Cohen, R.B.; Sur, R.K.; Raben, D.; Baselga, J.; Spencer, S.A.; Zhu, J. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.J. Aging and cancer. Oncol. Williston Park N. 2000, 14, 1731–1733, discussion 1734, 1739–1740. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, W.; Leeuw, J.R.J.; Hordijk, G.J.; Winnubst, J.A.M. Reasons for non-standard treatment in elderly patients with advanced head and neck cancer. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2005, 262, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Schroeff, M.P.; Derks, W.; Hordijk, G.J.; De Leeuw, R.J. The effect of age on survival and quality of life in elderly head and neck cancer patients: A long-term prospective study. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2007, 264, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacas, B.; Carmel, A.; Landais, C.; Wong, S.J.; Licitra, L.; Tobias, J.S.; Burtness, B.; Ghi, M.G.; Cohen, E.E.W.; Grau, C.; et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): An update on 107 randomized trials and 19,805 patients, on behalf of MACH-NC Group. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 156, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, C.; Lacas, B.; Pignon, J.P.; Le, Q.T.; Grégoire, V.; Grau, C.; Hackshaw, A.; Zackrisson, B.; Parmar, M.K.B.; Lee, J.-W.; et al. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer: An individual patient data network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildiers, H.; Heeren, P.; Puts, M.; Topinkova, E.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.G.; Extermann, M.; Falandry, C.; Artz, A.; Brain, E.; Colloca, G.; et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology Consensus on Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients with Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2595–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extermann, M. Evaluation of the Senior Cancer Patient: Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and Screening Tools for the Elderly. In ESMO Handbook of Cancer in the Senior Patient, 1st ed.; European Society of Medical Oncology Handbooks; Informa Healthcare; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Yeh, K.; Huang, J.; Chen, E.Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, C. Chemoradiotherapy in elderly patients with advanced head and neck cancer under intensive nutritional support. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 11, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szturz, P.; Wouters, K.; Kiyota, N.; Tahara, M.; Prabhash, K.; Noronha, V.; Castro, A.; Licitra, L.; Adelstein, D.; Vermorken, J.B. Weekly Low-Dose Versus Three-Weekly High-Dose Cisplatin for Concurrent Chemoradiation in Locoregionally Advanced Non-Nasopharyngeal Head and Neck Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Aggregate Data. Oncologist 2017, 22, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.B.; Edge, S.B.; Greene, F.L.; Byrd, D.R.; Brookland, R.K.; Washington, M.K.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Compton, C.C.; Hess, K.R.; Sullivan, D.C.; et al. (Eds.) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events-CTCAE-Version 4.1 Scale; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Forastiere, A.A.; Goepfert, H.; Maor, M.; Pajak, T.F.; Weber, R.; Morrison, W.; Glisson, B.; Trotti, A.; Ridge, J.A.; Chao, C.; et al. Concurrent Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy for Organ Preservation in Advanced Laryngeal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 2091–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forastiere, A.A.; Zhang, Q.; Weber, R.S.; Maor, M.H.; Goepfert, H.; Pajak, T.F.; Morrison, W.; Glisson, B.; Trotti, A.; Ridge, J.A.; et al. Long-Term Results of RTOG 91-11: A Comparison of Three Nonsurgical Treatment Strategies to Preserve the Larynx in Patients with Locally Advanced Larynx Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, V.; Joshi, A.; Patil, V.M.; Agarwal, J.; Ghosh-Laskar, S.; Budrukkar, A.; Murthy, V.; Gupta, T.; D’Cruz, A.K.; Banavali, S.; et al. Once-a-Week Versus Once-Every-3-Weeks Cisplatin Chemoradiation for Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer: A Phase III Randomized Noninferiority Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachaud, J.M.; Cohen-Jonathan, E.; Alzieu, C.; David, J.M.; Serrano, E.; Daly-Schveitzer, N. Combined postoperative radiotherapy and Weekly Cisplatin infusion for locally advanced head and neck carcinoma: Final report of a randomized trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 1996, 36, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny, M.M.; Peterson, B.L.; Kornblith, A.B.; Muss, H.B.; Wheeler, J.; Levine, E.; Bartlett, N.; Fleming, G.; Harvey, J. Cohen. Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation by Older Women with Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 2268–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoster, L.; Van Puyvelde, K.; Mohile, S.; Wedding, U.; Basso, U.; Colloca, G.; Rostoft, S.; Overcash, J.; Wildiers, H.; Steer, C.; et al. Screening tools for multidimensional health problems warranting a geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: An update on SIOG recommendations. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PACE participants. Shall we operate? Preoperative assessment in elderly cancer patients (PACE) can help. A SIOG surgical task force prospective study. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2008, 65, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellini, S.; Deantoni, C.L.; Paccagnella, M.; Casirati, A.; Pontara, A.; Marinosci, A.; Tresoldi, M.; Giordano, L.; Chiara, A.; Dell’Oca, I.; et al. The impact of nutritional intervention on quality of life and outcomes in patients with head and neck cancers undergoing chemoradiation. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1475930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymoortash, A.; Ferlito, A.; Halmos, G.B. Treatment in elderly patients with head and neck cancer: A challenging dilemma. HNO 2016, 64, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozec, A.; Poissonnet, G.; Chamorey, E.; Laout, C.; Vallicioni, J.; Demard, F.; Peyrade, F.; Follana, P.; Bensadoun, R.-J.; Chamorey, E.; et al. Radical ablative surgery and radial forearm free flap (RFFF) reconstruction for patients with oral or oropharyngeal cancer: Postoperative outcomes and oncologic and functional results. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009, 129, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, M.; D’Onofrio, I.; Belfiore, M.P.; Angrisani, A.; Caliendo, V.; Della Corte, C.M.; Pirozzi, M.; Facchini, S.; Caterino, M.; Guida, C.; et al. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Elderly Patients: Role of Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pignon, T.; Horiot, J.C.; Van Den Bogaert, W.; Van Glabbeke, M.; Scalliet, P. No age limit for radical radiotherapy in head and neck tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 1996, 32, 2075–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haehl, E.; Rühle, A.; David, H.; Kalckreuth, T.; Sprave, T.; Stoian, R.; Becker, C.; Knopf, A.; Grosu, A.-L.; Nicolay, N.H. Radiotherapy for geriatric head-and-neck cancer patients: What is the value of standard treatment in the elderly? Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller Von Der Grün, J.; Martin, D.; Stöver, T.; Ghanaati, S.; Rödel, C.; Balermpas, P. Chemoradiotherapy as Definitive Treatment for Elderly Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3508795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; O’Sullivan, B.; Waldron, J.; Lockwood, G.; Bayley, A.; Kim, J.; Cummings, B.; Dawson, L.A.; Hope, A.; Cho, J.; et al. Patterns of Care in Elderly Head-and-Neck Cancer Radiation Oncology Patients: A Single-Center Cohort Study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2011, 79, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, C.; Le Caer, H.; Ortholan, C.; Blot, E.; Even, C.; Rousselot, H.; Peyrade, F.; Sire, C.; Cupissol, D.; Pointreau, Y.; et al. ELAN-ONCOVAL (Elderly Head and Neck Cancer-Oncology Evaluation) study: Evaluation of the G8 screening tool and the ELAN geriatric evaluation (EGE) for elderly patients (pts) with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37 (Suppl. S15), 11541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, P.; Esposito, A.; Vecchio, S.; Nicolai, P.; Tarsitano, A.; Mirabile, A.; Ursino, S.; Cau, M.C.; Bonomo, P.; Marengoni, A.; et al. 864MO Role of geriatric assessment in tailoring treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer: The ELDERLY study. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, R.; Zumsteg, Z.S.; BrintzenhofeSzoc, K.; Trevino, K.M.; Gajra, A.; Korc-Grodzicki, B.; Epstein, J.B.; Bond, S.M.; Parker, I.; Kish, J.A.; et al. The Older Adult with Locoregionally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Knowledge Gaps and Future Direction in Assessment and Treatment. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 98, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neve, M.; Jameson, M.B.; Govender, S.; Hartopeanu, C. Impact of geriatric assessment on the management of older adults with head and neck cancer: A pilot study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2016, 7, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgioia, L.; De Felice, F.; Bacigalupo, A.; Alterio, D.; Argenone, A.; D’Angelo, E.; Desideri, I.; Franco, P.F.; Merlotti, A.; Musio, D.; et al. Results of a survey on elderly head and neck cancer patients on behalf of the Italian Association of Radiotherapy and Clinical Oncology (AIRO). Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2020, 40, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mamgani, A.; De Ridder, M.; Navran, A.; Klop, W.M.; De Boer, J.P.; Tesselaar, M.E. The impact of cumulative dose of cisplatin on outcome of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 274, 3757–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeim, A.; Aapro, M.; Subbarao, R.; Balducci, L. Supportive Care Considerations for Older Adults with Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2627–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boero, I.J.; Paravati, A.J.; Xu, B.; Ezra, E.W.; Cohen; Mell, L.K.; Le, Q.-T.; Murphy, J.D. Importance of Radiation Oncologist Experience Among Patients with Head-and-Neck Cancer Treated with Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grénman, R.; Chevalier, D.; Gregoire, V.; Myers, E.; Rogers, S. Treatment of head and neck cancer in the elderly: European Consensus (panel 6) at the EUFOS Congress in Vienna 2007. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 267, 1619–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, W.; De Leeuw, R.J.; Hordijk, G.J.; Winnubst, J.A. Quality of life in elderly patients with head and neck cancer one year after diagnosis. Head Neck 2004, 26, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szturz, P.; Vermorken, J.B. Treatment of Elderly Patients with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of Included Patients | Elderly (57 Patients) | Young (113 Patients) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median [IQR] | 72 [70–75] | 57 [27–65] |

| Age class | ||

| >65 | 12 (21.1%) | NA |

| >70 | 45 (78.9%) | NA |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 42 (73.7%) | 86 (24.0%) |

| Female | 15 (26.3%) | 27 (76.0%) |

| Adult Comorbidity Evaluation (ACE)-27 levels | ||

| Grade 1 | 6 (10.5%) | NA |

| Grade 2 | 36 (63.2%) | NA |

| Grade 3 | 15 (26.3%) | NA |

| Smoking | ||

| >10 packs/year | 38 (66.7%) | 55 (48.7%) |

| <10 packs/year | 6 (10.5%) | 20 (17.7%) |

| No | 13 (22.8%) | 38 (33.6%) |

| Alcohol | ||

| ≥500 mL | 5 (8.8%) | 12 (11.0%) |

| No or <500 mL | 52 (91.2%) | 101 (89.0%) |

| Drug abuse | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 57 (100.0%) | 113 (100.0%) |

| ECOG Performance Status Scale | ||

| 0 | 34 (59.6%) | 83 (73.5%) |

| 1 | 23 (40.4%) | 30 (26.5%) |

| Tumor staging | ||

| I | 0 | 4 (3.5%) |

| II | 2 (3.6%) | 10 (8.8%) |

| III | 14 (24.6%) | 41 (36.3%) |

| IV | 41 (71.9%) | 58 (51.4%) |

| Tumor location | ||

| Oral cavity | 9 (15.8%) | 16 (14.2%) |

| Oropharynx | 23 (40.3%) | 52 (46.0%) |

| Hypopharynx | 5 (8.8%) | 8 (7.1%) |

| Larynx | 9 (15.8%) | 8 (7.1%) |

| Nasopharynx | 2 (3.5%) | 17 (15%) |

| Nasal cavity | 4 (7.02%) | 4 (3.5%) |

| Paranasal sinuses | 1 (1.7%) | 0 |

| Salivary glands | 3 (5.3%) | 7 (6.2%) |

| Thyroid | 1 (1.7%) | 0 |

| External auditory canal | 0 | 1 (0.1%) |

| G8 score, n (%) | ||

| ≥15 | 43 (75.4%) | NA |

| <15 | 14 (24.6%) | NA |

| Elderly | Young | Odds Ratio | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermatitis | ||||

| G0–1 | 23 (40.4%) | 52 (44.4%) | 1 | 0.609 |

| G ≥ 2 | 34 (59.6%) | 65 (55.6%) | 1.18 | |

| Mucositis | ||||

| G0–1 | 33 (57.9%) | 55 (47.1%) | 1 | 0.179 |

| G ≥ 2 | 24 (42.1%) | 62 (52.9 %) | 0.65 | |

| Dysphagia | ||||

| G0–1 | 36 (63.2%) | 72 (61.5%) | 1 | 0.836 |

| G ≥ 2 | 21 (36.8%) | 45 (38.5%) | 0.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deantoni, C.L.; Galli, A.; Valsecchi, D.; Porcu, L.; Tranò, L.; Giannini, L.; Dell’Oca, I.; Chiara, A.; Gioffrè, V.; Tresoldi, M.; et al. Clinical Outcome in Elderly Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated with Concomitant Cisplatin and Radiotherapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17183007

Deantoni CL, Galli A, Valsecchi D, Porcu L, Tranò L, Giannini L, Dell’Oca I, Chiara A, Gioffrè V, Tresoldi M, et al. Clinical Outcome in Elderly Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated with Concomitant Cisplatin and Radiotherapy. Cancers. 2025; 17(18):3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17183007

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeantoni, Chiara Lucrezia, Andrea Galli, Davide Valsecchi, Luca Porcu, Lucrezia Tranò, Laura Giannini, Italo Dell’Oca, Anna Chiara, Vittorio Gioffrè, Moreno Tresoldi, and et al. 2025. "Clinical Outcome in Elderly Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated with Concomitant Cisplatin and Radiotherapy" Cancers 17, no. 18: 3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17183007

APA StyleDeantoni, C. L., Galli, A., Valsecchi, D., Porcu, L., Tranò, L., Giannini, L., Dell’Oca, I., Chiara, A., Gioffrè, V., Tresoldi, M., Di Muzio, N. G., Giordano, L., & Mirabile, A. (2025). Clinical Outcome in Elderly Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated with Concomitant Cisplatin and Radiotherapy. Cancers, 17(18), 3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17183007