The Role of Perceived Benefits in Buffering Gastrointestinal-Symptom Burden Among Post-Operative Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Six-Month Longitudinal Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Demographics

3.2. Descriptive, ICC, and Correlation Analyses

3.3. HLM Model for PCS

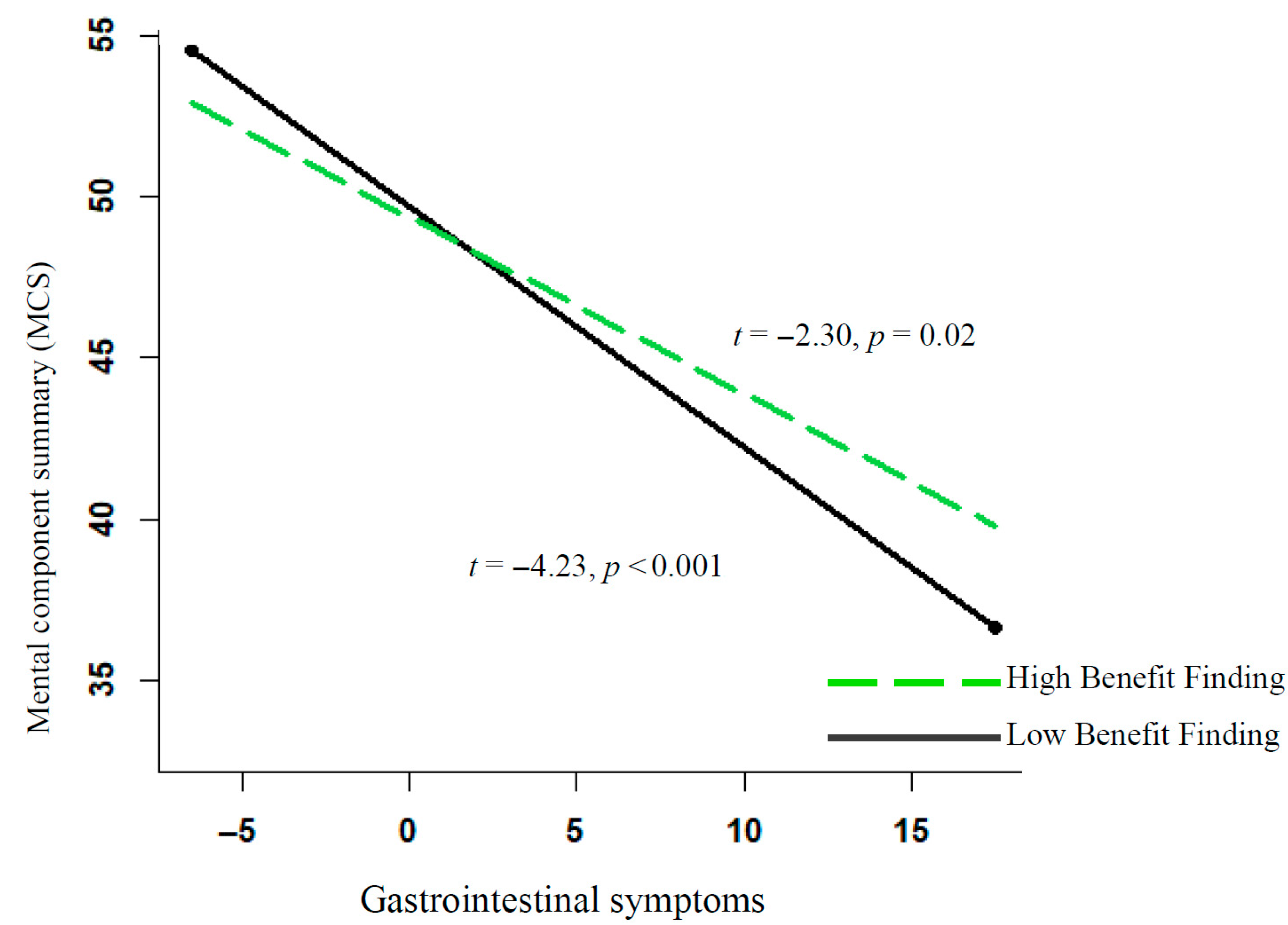

3.4. HLM Model for MCS

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. Available online: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/Pages/List.aspx?nodeid=269 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- American Cancer Society. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- De Ligt, K.; Heins, M.; Verloop, J.; Ezendam, N.; Smorenburg, C.; Korevaar, J.; Siesling, S. The impact of health symptoms on health-related quality of life in early-stage breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 178, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenzik, K.M.; Ganz, P.A.; Martin, M.Y.; Petersen, L.; Hays, R.D.; Arora, N.; Pisu, M. How much do cancer-related symptoms contribute to health-related quality of life in lung and colorectal cancer patients? A report from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium. Cancer 2015, 121, 2831–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrl, K.; Guren, M.G.; Astrup, G.L.; Småstuen, M.C.; Rustøen, T. High symptom burden is associated with impaired quality of life in colorectal cancer patients during chemotherapy: A prospective longitudinal study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 44, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, C.; Bulkley, J.; Corley, D.A.; Madrid, S.; Davis, A.Q.; Hesselbrock, R.; Kurtilla, F.; Anderson, C.K.; Arterburn, D.; Somkin, C.P.; et al. Health care improvement and survivorship priorities of colorectal cancer survivors: Findings from the PORTAL colorectal cancer cohort survey. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molassiotis, A.; Yates, P.; Li, Q.; So, W.; Pongthavornkamol, K.; Pittayapan, P.; Komatsu, H.; Thandar, M.; Yi, M.; Chacko, S.T.; et al. Mapping unmet supportive care needs, quality-of-life perceptions and current symptoms in cancer survivors across the Asia-Pacific region: Results from the International STEP Study. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2552–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, C.; Stack, J.; O’Ceilleachair, A.; Denieffe, S.; Gooney, M.; McKnight, M.; Sharp, L. Colorectal cancer survivors: An investigation of symptom burden and influencing factors. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.-J.; Lai, H.-J.; Liu, Y.-M.; Liao, M.-N.; Tung, T.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Beaton, R.D.; Jane, S.-W.; Huang, H.-P. Unmet Care Needs of Colorectal Cancer Survivors in Taiwan and Related Predictors. J. Nurs. Res. 2025, 33, e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, J.V.-T.; Matusko, N.; Hendren, S.; Regenbogen, S.E.; Hardiman, K.M. Patient-reported unmet needs in colorectal cancer survivors after treatment for curative intent. Dis. Colon Rectum 2019, 62, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E. SF-36 Health Survey. Manual and Interpretation Guide; The Health Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 6:1–6:22. [Google Scholar]

- Shand, L.K.; Cowlishaw, S.; Brooker, J.E.; Burney, S.; Ricciardelli, L.A. Correlates of post-traumatic stress symptoms and growth in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.E.; Meyerowitz, B.E.; Bernaards, C.A.; Rowland, J.H.; Ganz, P.A.; Desmond, K.A. Perceptions of positive meaning and vulnerability following breast cancer: Predictors and outcomes among long-term breast cancer survivors. Ann. Behav. Med. 2005, 29, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, I.-Y.; Jane, S.-W.; Hsu, H.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Tsai, W.-S.; Young, C.-Y.; Beaton, R.D.; Huang, H.-P. The longitudinal trends of care needs, psychological distress, and quality of life and related predictors in Taiwanese colorectal cancer survivors. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 39, 151424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, F.; Jin, L.; Xian, X. Correlated factors of posttraumatic growth in patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2025, 12, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Thong, M.S.; Doege, D.; Koch-Gallenkamp, L.; Bertram, H.; Eberle, A.; Holleczek, B.; Waldmann, A.; Zeissig, S.R.; Pritzkuleit, R.; et al. Prevalence of benefit finding and posttraumatic growth in long-term cancer survivors: Results from a multi-regional population-based survey in Germany. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Chmielewski, J.; Blank, T.O. Post-traumatic growth: Finding positive meaning in cancer survivorship moderates the impact of intrusive thoughts on adjustment in younger adults. Psycho-Oncology 2010, 19, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L. Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 257–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomich, P.L.; Helgeson, V.S. Posttraumatic growth following cancer: Links to quality of life. J. Trauma. Stress 2012, 25, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.W.; Hoyt, M.A. Benefit finding and diurnal cortisol after prostate cancer: The mediating role of positive affect. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Ganz, P.A. Life after diagnosis and treatment of cancer in adulthood: Contributions from psychosocial oncology research. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.L.; Charles, S.T.; Gunaratne, M.; Baxter, N.N.; Cotterchio, M.; Cohen, Z.; Gallinger, S. Symptom severity and quality of life among long-term colorectal cancer survivors compared with matched control subjects: A population-based study. Dis. Colon Rectum 2018, 61, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.J.; Yang, G.S.; Syrjala, K. Symptom experiences in colorectal cancer survivors after cancer treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 43, E132–E158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh-Wu, S.F.; Anglade, D.; Gattamorta, K.; Downs, C.A. Relationships between colorectal cancer survivors’ positive psychology, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2023, 32, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, V.S.; Reynolds, K.A.; Tomich, P.L. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roepke, A.M. Psychosocial interventions and posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.; Bai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Patterns and predictors of symptom burden and posttraumatic growth among patients with cancer: A latent profile analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, J.E.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Epel, E. Is benefit finding good for your health? Pathways linking positive life changes after stress and physical health outcomes. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.W.T.; Chang, C.S.; Chen, S.T.; Chen, D.R.; Hsu, W.Y. Identification of posttraumatic growth trajectories in the first year after breast cancer surgery. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danhauer, S.C.; Russell, G.; Case, L.D.; Sohl, S.J.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Addington, E.L.; Triplett, K.; Van Zee, K.J.; Naftalis, E.Z.; Levine, B.; et al. Trajectories of posttraumatic growth and associated characteristics in women with breast cancer. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.G.; Novoa, D.C. Meaning-making following spinal cord injury: Individual differences and within-person change. Rehabil. Psychol. 2013, 58, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, V.; Merx, H.; Stegmaier, C.; Ziegler, H.; Brenner, H. Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: A population-based study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4829–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.; Haes, J.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A qualityof-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whistance, R.; Conroy, T.; Chie, W.; Costantini, A.; Sezer, O.; Koller, M.; Johnson, C.; Pilkington, S.; Arraras, J.; Ben-Josef, E.; et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 questionnaire module to assess health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 3017–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, L.K.; Bacik, J.; Savatta, S.G.; Gottesman, L.; Paty, P.B.; Weiser, M.R.; Guillem, J.G.; Minsky, B.D.; Kalman, M.; Thaler, H.T.; et al. The development of a validated instrument to evaluate bowel function after sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2005, 48, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, W.L.; Hahn, E.A.; Mo, F.; Hernandez, L.; Tulsky, D.S.; Cella, D. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) quality of life instrument. Qual. Life Res. 1999, 8, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmertsen, K.J.; Laurberg, S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: Development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann. Surg. 2012, 255, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S.; Cheong, Y.F.; Congdon, R.; du Toit, M. HLM 7: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling; Scientific Software International: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2002; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, O.-M.; Underhill, A.T.; Berry, J.W.; Luo, W.; Elliott, T.R.; Yoon, M. Analyzing longitudinal data with multilevel models: An example with individuals living with lower extremity intra-articular fractures. Rehabil. Psychol. 2008, 53, 370–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Curran, P.J.; Bauer, D.J. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, K.I. Benefit finding in multiple sclerosis and associations with positive and negative outcomes. Health Psychol. 2005, 24, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascio, A.L.; Napolitano, D.; Latina, R.; Dabbene, M.; Bozzetti, M.; Sblendorio, E.; Mancin, S.; Sguanci, M.; Piredda, M.; De Marinis, M.G. The Relationship between Pain Catastrophizing and Spiritual Well-Being in Adult Cancer Patients: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2025, 70, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.J.; Phillips, C.A.; Glover, N.; Richardson, A.L.; D’Souza, J.M.; Cunningham-Erdogdu, P.; Gallagher, M.W. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between posttraumatic growth, anxiety, and depression. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 3703–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Fleur, R.G.; Ream, M.; Walsh, E.A.; Antoni, M.H. Cognitive behavioral stress management affects different dimensions of benefit finding in breast cancer survivors: A multilevel mediation model. Psychol. Health 2025, 40, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfeki, H.; Alharbi, R.A.; Juul, T.; Drewes, A.M.; Christensen, P.; Laurberg, S.; Emmertsen, K.J. Chronic pain after colorectal cancer treatment: A population-based cross-sectional study. Color. Dis. 2025, 27, e17296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, A.H.; Heuvelings, D.J.; Sylla, P.; van Loon, Y.-T.; Melenhorst, J.; Bouvy, N.D.; Kimman, M.L.; Breukink, S.O. Impact of anastomotic leakage after colorectal cancer surgery on quality of life: A systematic review. Dis. Colon Rectum 2025, 68, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.T.; Pham, V.N.T.; Do, M.D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Tran, T.T. Long-term outcomes and genetic mutation patterns in early-onset colorectal cancer. Asian J. Surg. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Trabulsi, N.H.; Alkhalifah, H.A.; Alrefaei, M.I.; Alhamed, W.A.; Alkhalifah, Z.A.; Al-Hajeili, M.; Alturki, H.; Shabkah, A.A.; Saleem, A.; Farsi, A. Effect of adherence to prophylaxis on the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) following colorectal cancer surgery: A retrospective record review. Asian J. Surg. 2025, 48, 3514–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.-L.; Huang, Y.-J.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.-M. Comparison of robotic reduced-port and laparoscopic approaches for left-sided colorectal cancer surgery. Asian J. Surg. 2023, 46, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bananzade, A.; Dehghankhalili, M.; Bahrami, F.; Tadayon, S.M.K.; Ghaffarpasand, F. Outcome of early versus late ileostomy closure in patients with rectal cancers undergoing low anterior resection: A prospective cohort study. Asian J. Surg. 2023, 46, 4277–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 70) | (n = 59) | (n = 56) | ||

| Scores Range | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 0–24 | 6.24 (4.84) | 6.19 (4.96) | 5.59 (4.02) |

| Benefit Finding | 6–30 | 19.14 (4.79) | 19.61 (4.55) | 19.77 (5.00) |

| Physical component summary (PCS) scores | 0–100 | 50 (8.66) | 50 (8.76) | 50 (8.66) |

| Mental component summary (MCS) scores | 0–100 | 50 (10.15) | 50 (9.83) | 50 (8.47) |

| Physical Component Summary (PCS) | Mental Component Summary (MCS) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | b | SE | t | Effect Size r | b | SE | t | Effect Size r |

| Within-person effect | ||||||||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | −0.70 | 0.13 | −5.26 *** | 0.52 | −0.55 | 0.13 | −4.18 *** | 0.44 |

| Benefit finding | −0.07 | 0.12 | −0.58 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.12 | −0.54 | 0.06 |

| Symptoms * benefit finding | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.98 * | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.00 * | 0.23 |

| Time | −0.05 | 0.58 | 0.93 | 0.11 | −0.03 | 0.53 | 0.95 | 0.11 |

| Between-person effect | ||||||||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 2.70 ** | 0.30 |

| Gender | −1.06 | 1.47 | −0.72 | 0.08 | 0.81 | 1.83 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

| Income | 2.04 | 0.72 | 2.83 ** | 0.31 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.11 |

| Stage | 0.34 | 0.49 | −0.72 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 0.21 | 0.02 |

| Constant | 50.60 | 1.30 | 38.78 *** | 49.37 | 1.55 | 31.76 *** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, M.-W.; Wang, A.W.-T.; Chang, C.-S. The Role of Perceived Benefits in Buffering Gastrointestinal-Symptom Burden Among Post-Operative Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Six-Month Longitudinal Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172934

Chang M-W, Wang AW-T, Chang C-S. The Role of Perceived Benefits in Buffering Gastrointestinal-Symptom Burden Among Post-Operative Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Six-Month Longitudinal Study. Cancers. 2025; 17(17):2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172934

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Ming-Wei, Ashley Wei-Ting Wang, and Cheng-Shyong Chang. 2025. "The Role of Perceived Benefits in Buffering Gastrointestinal-Symptom Burden Among Post-Operative Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Six-Month Longitudinal Study" Cancers 17, no. 17: 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172934

APA StyleChang, M.-W., Wang, A. W.-T., & Chang, C.-S. (2025). The Role of Perceived Benefits in Buffering Gastrointestinal-Symptom Burden Among Post-Operative Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Six-Month Longitudinal Study. Cancers, 17(17), 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172934