Healthcare Resource Utilization and Treatment Costs for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: A PETHEMA Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

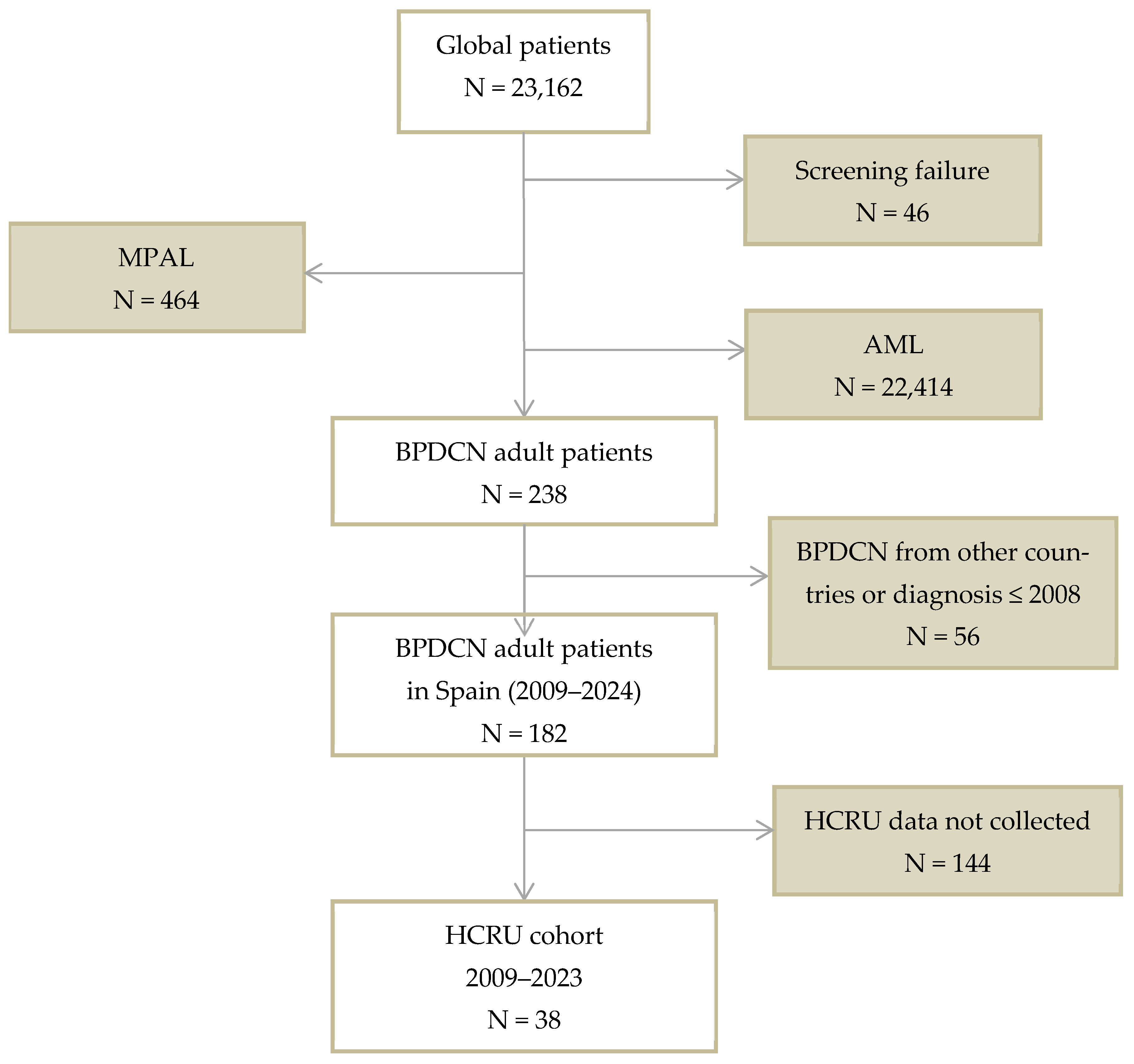

2.1. Patients and Study Design

2.2. Objectives

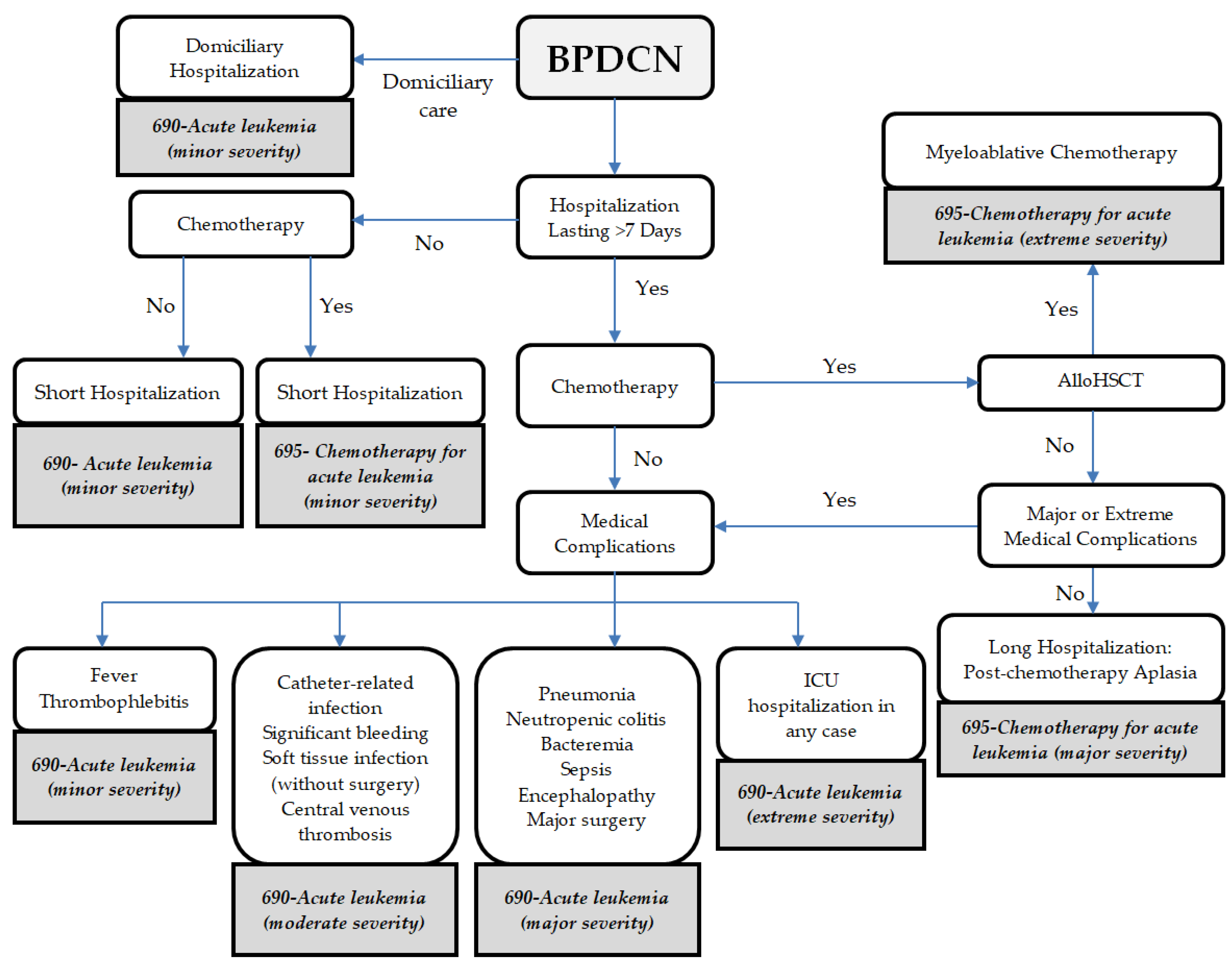

2.3. Calculation of Hospital Reimbursement

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patients

3.2. Hospitalizations and Reimbursement During the Chemotherapy Period

3.3. Hospitalizations and Reimbursement for Patients Who Underwent Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

3.4. Hospitalizations and Reimbursement for Patients with Tagraxofusp as First-Line Treatment

3.5. Reasons for Hospitalizations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALL | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| alloHSCT | Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation |

| AML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| BPDCN | Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm |

| CD123 | Cluster of Differentiation 123 |

| CHT | Chemotherapy |

| CR | Complete Remission |

| CRi | Complete Remission with incomplete hematologic recovery |

| DRG | Diagnosis-Related Group |

| FLUGA | Fludarabine/Cytarabine/Filgrastim |

| FLAG-IDA | Fludarabine/Cytarabine/Filgrastim/Idarubicin |

| HCRU | Healthcare Resource Utilization |

| HYPERCVAD | Cyclophosphamide/Vincristine/Doxorubicin/Dexamethasone |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LDAC | Low-Dose Cytarabine |

| MPAL | Mixed-Phenotype Acute Leukemia |

| NA | Not Applicable |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PETHEMA | Programa Español de Tratamientos en Hematología |

| RBC | Red Blood Cells |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SMILE | Dexamethasone/Methotrexate/Ifosfamide/L-Asparaginase/Etoposide |

References

- Navarro Vicente, I.; Solana-Altabella, A.; Sobas, M.; Serrano, J.; Karasek, M.; Perez Encinas, M.; Labrador, J.; de la Fuente, C.; Salamero, O.; Colmenares Gil, R.; et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes in 228 Patients Diagnosed with Blastic Plasmocytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: A Pethema/PALG Study. Blood 2024, 144, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Haddadin, M.; Upadhyay, V.A.; Grussie, E.; Mehta-Shah, N.; Brunner, A.M.; Louissaint, A.; Lovitch, S.B.; Dogan, A.; Fathi, A.T.; et al. Multicenter Analysis of Outcomes in Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm Offers a Pretargeted Therapy Benchmark. Blood 2019, 134, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Martín, L.; López, A.; Vidriales, B.; Caballero, M.D.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Ferreira, S.I.; Lima, M.; Almeida, S.; Valverde, B.; Martínez, P.; et al. Classification and Clinical Behavior of Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasms According to Their Maturation-Associated Immunophenotypic Profile. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 19204–19216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pemmaraju, N.; Lane, A.A.; Sweet, K.L.; Stein, A.S.; Vasu, S.; Blum, W.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Wang, E.S.; Duvic, M.; Sloan, J.M.; et al. Tagraxofusp in Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic-Cell Neoplasm. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, C.G.; Pagano, L. Tagraxofusp for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: A 2-Speed Cure in the United States and European Union. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 7084–7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osakidetza. Coste Efectivo de los Servicios de Salud. 2024. Available online: https://www.osakidetza.euskadi.eus/coste-efectivo-servicios-de-salud/webosk00-tbgcon/es/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya. ORDEN SLT/168/2024, de 15 de Julio, por la que se Determinan para el año 2024 los Precios Unitarios para la Contraprestación de la Atención Hospitalaria y Especializada; Spain. 2024. Available online: https://portaldogc.gencat.cat/utilsEADOP/PDF/9207/2038890.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Oblikue Consulting. ESalud—Información Económica Del Sector Sanitario. 2024. Available online: https://esalud.oblikue.com/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Solana-Altabella, A.; Boluda, B.; Rodríguez-Veiga, R.; Cano, I.; Acuña-Cruz, E.; Blanco, A.; Marco-Ayala, J.; de la Puerta, R.; Díaz-González, Á.; Piñana, J.L.; et al. Healthcare Resource Utilization in Adult Patients with Relapsed/Refractory FLT3 Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Retrospective Chart Review from Spain. Eur. J. Haematol. 2021, 106, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandya, B.J.; Chen, C.-C.; Medeiros, B.C.; McGuiness, C.B.; Wilson, S.; Horvath Walsh, L.E.; Wade, R.L. Economic and Clinical Burden of Relapsed and/or Refractory Active Treatment Episodes in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) in the USA: A Retrospective Analysis of a Commercial Payer Database. Adv. Ther. 2019, 36, 1922–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datosmacro.com—Expansion—Diario. Económico e Información de Mercado Gasto Público Salud Per Capita 2023; 2023. Available online: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/estado/gasto/salud/espana (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Nationwide Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Available online: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Datosmacro.com—Expansion—Diario Económico e Información de Mercado Comparativa de la Evolución de Esperanza de Vida al Nacer de Estados Unidos vs España. Available online: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/paises/comparar/usa/espana?sc=XE24 (accessed on 21 March 2025).

| Characteristic | n = 38 |

|---|---|

| Age at index date, years | |

| Median [IQR] | 66 [18] |

| Mean (SD) | 61 (16) |

| Men, number (%) | 32 (84) |

| Status at the end of follow-up, number (%) | |

| Deceased | 25 (66) |

| Alive | 13 (34) |

| Type of scheme at first-line, number (%) | |

| Intensive | 22 (58) |

| Non-intensive | 16 (42) |

| First-line treatment received, number (%) | |

| AML-Like | 12 (32) |

| Idarubicin + cytarabine (3 + 7) | 7 (18) |

| FLAG-IDA | 3 (8) |

| LDAC | 1 (3) |

| FLUGA | 1 (3) |

| ALL-Like | 6 (16) |

| HYPERCVAD | 6 (16) |

| Lymphoma-Like | 6 (16) |

| CHOP | 5 (13) |

| SMILE | 1 (3) |

| Targeted therapies † | 14 (37) |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 8 (21) |

| Tagraxofusp | 6 (16) |

| Patients with at least one hospitalization at period, number (%) | |

| CHT | 35 (92) |

| alloHSCT | 18 (47) |

| Healthcare Resource Unit | Inpatient Hospitalizations | External Consultation Visits | Day Hospital Visits | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per hospitalization | ||||

| Number of hospitalization or visits | 187 | 1480 | 1100 | NA |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] length of stay per episode, days | 20 (28) 11 [23] | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | NA |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] reimbursement per hospitalization or visit, EUR | 18,118 (19,345) 15,700 [20,392] | 231 (0) | 262 (0) † | NA |

| Per patient | ||||

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] number of stays | 5 (3) 4 [5] | NA | NA | NA |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] days of hospitalization | 96 (100) 71 [87] | NA | NA | NA |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] reimbursement, EUR | 89,158 (77,408) 72,624 [69,089] | 7439 (6371) 5062 [9359] | 12,507 (15,424) 7271 [20,707] | 109,104 (88,499) 93,085 [101,673] |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] number RBC packages transfusion | 21 (26) 12 [18] | NA | 10 (15) 4 [8] | 30 (36) 18 [33] |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] number platelet transfusion | 27 (41) 14 [26] | NA | 11 (21) 2 [14] | 38 (57) 15 [37] |

| Patients with ICU hospitalization, number (%) | 9 (24) | NA | NA | NA |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] days ICU hospitalization of patients admitted at ICU | 10 (11) 5 [10] | NA | NA | 10 (11) 5 [10] |

| Healthcare Resource Unit | Inpatient Hospitalizations | External Consultation Visits | Day Hospital Visits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per hospitalization | |||

| Number of hospitalization or visits | 128 | 723 | 676 |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] length of stay, days | 16 (15) 10 [18] | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] reimbursement, EUR | 12,427 (7979) 9674 [10,085] | 231 (0) | 262 (0) |

| Per patient | |||

| Number of patients | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] number of stays | 3 (2) 3 [4] | 19 (16) 17 [19] | 18 (23) 8 [23] |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] days of hospitalization | 54 (39) 56 [54] | NA | NA |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] reimbursement, EUR | 41,858 (27,038) 42,233 [39,465] | 3634 (3115) 3247 [3629] | 4793 (6195) 2291 [6198] |

| Healthcare Resource Unit | Inpatient Hospitalizations | External Consultation Visits | Day Hospital Visits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per hospitalization | |||

| Number of hospitalization or visits | 59 | 757 | 424 |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] length of stay, days | 27 (44) 16 [26] | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] reimbursement, EUR | 30,464 (28,883) 27,017 [38,254] | 231 (0) | 691 (0) |

| Per patient | |||

| Number of patients | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] number of stays | 3 (2) 3 [3] | 33 (34) 19 [55] | 24 (25) 17 [31] |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] days of hospitalization | 89 (92) 54 [50] | NA | NA |

| Mean (SD), median [IQR] reimbursement, EUR | 99,855 (76,679) 72,990 [44,875] | 16,287 (17,174) 11,754 [21,434] | 6356 (6462) 3629 [10,505] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solana-Altabella, A.; Navarro-Vicente, I.; Rodríguez-Arbolí, E.; Noriega, V.; Serrano, J.; Bernal, T.; Carrasco-Baraja, V.; Garcia-Boyero, R.; Olivier Cornacchia, C.; Algarra, L.; et al. Healthcare Resource Utilization and Treatment Costs for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: A PETHEMA Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172844

Solana-Altabella A, Navarro-Vicente I, Rodríguez-Arbolí E, Noriega V, Serrano J, Bernal T, Carrasco-Baraja V, Garcia-Boyero R, Olivier Cornacchia C, Algarra L, et al. Healthcare Resource Utilization and Treatment Costs for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: A PETHEMA Study. Cancers. 2025; 17(17):2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172844

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolana-Altabella, Antonio, Irene Navarro-Vicente, Eduardo Rodríguez-Arbolí, Victor Noriega, Josefina Serrano, Teresa Bernal, Vicente Carrasco-Baraja, Raimundo Garcia-Boyero, Carmen Olivier Cornacchia, Lorenzo Algarra, and et al. 2025. "Healthcare Resource Utilization and Treatment Costs for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: A PETHEMA Study" Cancers 17, no. 17: 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172844

APA StyleSolana-Altabella, A., Navarro-Vicente, I., Rodríguez-Arbolí, E., Noriega, V., Serrano, J., Bernal, T., Carrasco-Baraja, V., Garcia-Boyero, R., Olivier Cornacchia, C., Algarra, L., López-Briz, E., Mena-Durán, A., Solano-Tovar, J., Botella-Prieto, C., Sánchez-Sánchez, S., Bergua-Burgues, J. M., Lloret-Madrid, P., Rodenas-Rovira, M., Boluda, B., ... Montesinos, P. (2025). Healthcare Resource Utilization and Treatment Costs for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: A PETHEMA Study. Cancers, 17(17), 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172844