End-of-Life Cancer Care Interventions for Racially and Ethnically Diverse Populations in the USA: A Scoping Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

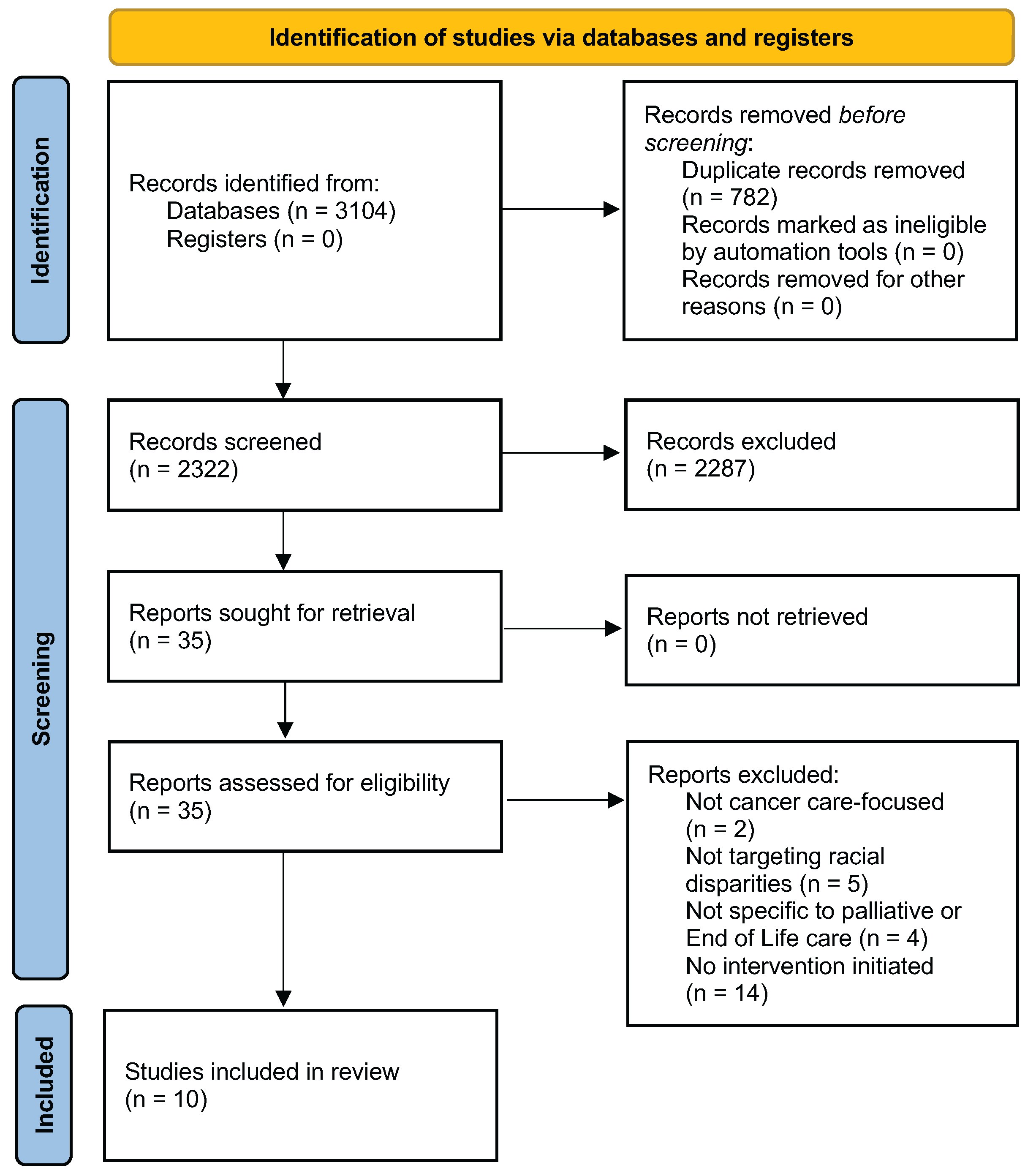

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Screening for Study Eligibility

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Intervention Design

3.3. Intervention Tailoring for Racial and Ethnic Populations

3.4. Intervention Implementation Challenges

3.5. Intervention Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist [22]

| Section | Item | PRISMA-ScR Checklist Item | Reported on Page # |

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| Abstract | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 2 |

| Introduction | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 3 |

| Methods | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 4 |

| Eligibility Criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 4 |

| Information Sources | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 4 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 19 |

| Selection of Sources of Evidence | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 4 |

| Data Charting Process | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 5 |

| Data Items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 4–5 |

| Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | n/a |

| Synthesis of Results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 4–5 |

| Results | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 4–5 |

| Characteristics of Sources of Evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 5–11 |

| Critical Appraisal Within Sources of Evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | n/a |

| Results of Individual Sources of Evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 5–11 |

| Synthesis of Results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 5–11 |

| Discussion | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 11 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 15 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 15 |

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 16 |

Appendix B. Search Strategy Keywords Applied to Ovid MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL with Full Text (EBSCOhost), and Scopus (Elsevier)

| Ovid MEDLINE |

|

| CINAHL |

|

| Scopus |

|

Appendix C. Intervention Design Categories, Category Definitions and Exemplar Quotes

| Intervention Design Category | Category Definitions | Exemplar Quotes (Study) |

| Communication Skills Programs for Patients, Caregivers, Researchers, and Clinicians | Programs intended to develop culturally competent communication skills for health-related end-of-life conversations among patients, caregivers, researchers, and clinicians. | “The goal of the present study was to develop a culturally competent communication coaching intervention to promote ACP among Latino patients with advanced cancer.” (Shen)

“We aimed to assess the acceptability of the SICG among African Americans with advanced cancer and their clinicians…The Serious Illness Conversation Guide (SICG) was developed to provide clinicians with a structured, patient-centered approach to SIC using tested language to communicate prognosis and elicit patients’ goals, values, and priorities that inform decision-making… We recruited a convenience sample of oncologists from 2 health centers to complete training in the use of the SICG.” (Sanders) |

| Education Programs for Patients | Programs intended to educate patients with cancer by incorporating culturally relevant themes. | “This study aims to adapt a video-based, multimedia chemotherapy educational intervention to meet the needs of US Latinos with advanced gastrointestinal malignancies… The intervention centers upon conversations with 12 Latino patients about their treatment experiences; video clips highlight culturally relevant themes (personalismo, familismo, faith, communication gaps, prognostic information preferences).” (Leiter) |

| Navigation and Support Programs for Patients and Caregivers | Programs intended to offer personalized and culturally-tailored guidance, education, and support to patients and caregivers from specific ethnic and racial communities throughout the care journey. | “Intervention patients received at least 5 home visits from a PN and the educational packet…Patient navigators completed detailed field notes, including tracking the number of contacts and visit length and content. The research team reviewed field notes to ensure intervention fidelity.” (Fischer)

“In this study, we first report adapting and integrating the counseling and patient navigator interventions followed by a pilot study of the combined intervention, puente para cuidar (bridge to caring), to understand and improve the feasibility of the integrated intervention.” (Bekelman) “This study sought to (a) implement new volunteer support teams for African Americans with advanced cancer in two distinct regions and (b) evaluate support teams’ ability to improve support, awareness of services, and quality of life for these patients…Study participants comprised two groups—support team volunteers and persons with advanced cancer…Support team volunteers were nonprofessionals recruited from the same geographic and social communities of participating cancer patients.” (Hanson 2014) |

| Training Programs for Health Workers and Community Leaders | Programs intended to equip community health workers and local leaders with the knowledge, skills, and cultural sensitivity needed to support individuals facing serious illness, promote palliative care awareness, and provide peer-based guidance within their communities. | “Lay health advisors were recruited through African American church leaders and health ministries… Investigators delivered a day-long training, offered several times. Participants practiced approaches for communicating with, advising, and supporting persons who faced serious illness, including sensitivity to confidentiality and boundaries of peer support. Lay health advisors then met monthly for 1 year to share their outreach experiences, discuss barriers, and suggest ways to improve peer support. They also participated in discussions with hospice providers, cancer support group leaders, and supportive care professionals.” (Hanson 2013)

“The nurse-led palliative care program, comprising 4 nurses and a medical anthropologist, trained Latino community leaders in knowledge of palliative care and advance care planning as well as how to share information about advance care planning and home-based symptom management. The palliative care lay advisors (PCLA) had to be over 18 years old, able to read and write Spanish and English, willing to assist Latinos with cancer, and have reliable transportation.” (Johnson) “This study introduces a novel Palliative Care Curriculum and Training Plan for CHWs [Community Health Workers], tailored to the specific needs of African American patients with advanced cancer.” (Monton) “Fifteen Latino community leaders completed a 10-hour palliative care training program and then served as palliative care LHAs.” (Larson) |

Appendix D. Intervention Tailoring for Racial and Ethnic Population Categories, Category Definitions, and Exemplar Quotes

| Intervention Tailoring Category | Category Definitions | Exemplar Quotes (Study) |

| Trust and Faith-based Values | Tailoring that leverages faith-based principles and values, building trust by engaging trusted community members who share the racial and ethnic backgrounds of those they serve. |

“Implementation of this peer support model was based on the socioecological theory of community health promotion using existing social networks (Golden & Earp, 2012; McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988). Lay health advisors were recruited through African American church leaders and health ministries. Recruited individuals were asked to invite others whom they regarded as natural helpers. Publicity materials were included in church bulletins and in news media reaching the African American community. To be included in training, participants had to complete a short application describing personal attributes, spiritual gifts, and prior experience with serious illness and provide three references who endorsed their fitness for the lay health advisor role.” (Hanson 2013) “Peer support interventions are used to extend health information and practical, emotional, and spiritual support beyond health care settings (Fisher, Earp, Maman, & Zolotor, 2010). These interventions are based on the socio-ecological theory of community health promotion, which acknowledges the important role of trusted sources for health information within social networks (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988)… We developed a volunteer peer support team program for African Americans facing advanced cancer, called Circles of Care.” (Hanson 2014) “This study introduces a novel Palliative Care Curriculum and Training Plan for CHWs, tailored to the specific needs of African American patients with advanced cancer. The pedagogical approach and interdisciplinary nature of curriculum development can be adapted and applied to a range of healthcare domains where Community Health Workers (CHW) may be utilized to address health disparities.” (Monton) |

| Literacy, and Faith-based Values | Tailoring that incorporates faith-based principles and adapts language to improve understanding and health literacy. | “The focus group interview solicited reactions to the SICG language, questions, content, and delivery. Participants were asked about a proposed new question in the guide: “What gives you strength as you think about the future with your illness?” This question was added for piloting based on research demonstrating the importance of family support and religious faith in ACP among Black Americans and input from researchers whose focus is health disparities.” (Sanders) |

| Language, Literacy, and Cultural Values | Cultural tailoring to align with patients’ language preferences, literacy levels, and core cultural values to improve understanding and engagement in care. |

“The navigators reviewed the written materials (workbook and illustrative case vignettes) of the therapy intervention and made three key recommendations: (a) revise the written materials to ensure literacy level was at the fifth- to sixth-grade reading level, (b) use videos to convey the story and core messages of the written illustrative case vignettes, and (c) adapt the vignettes to include aspects of Latina/o culture. Paired team members edited the workbook through an iterative process to achieve sixth-grade reading level, as determined by Reading IO. Next, advisory panel navigators were paired with an investigator and worked in partnership to rewrite the vignettes in the existing patient materials using surface-level and deep cultural tailoring. Surface-level cultural tailoring ensures that the people being portrayed in materials look like the people being targeted. Deep cultural tailoring includes integrating core values into the materials.”(Bekelman) “The objective of this study was to investigate if a culturally tailored PN [Patient Navigator] intervention can improve PC [Palliative Care] outcomes (increased ACP, improved pain management, and greater hospice use) for Latino adults with advanced cancer... All participants (control and intervention) received a culturally tailored packet of written information about ACP, pain management, hospice use, and a study-specific advance directive (AD)… An interdisciplinary, bicultural community advisory panel helped select materials…Materials were at a fifth-grade reading level and available in English and Spanish, per patient preference…Cultural Values were described in eTable 1 as utilizing core values in all messaging (cultural tailoring), Importance of family (familia or familism), Personal Connections based on trust (confianza), and value/build strong interpersonal connections (personalismo).” (Fischer) “The nurse-led palliative care program, comprising 4 nurses and a medical anthropologist, trained Latino community leaders in knowledge of palliative care and advance care planning as well as how to share information about advance care planning and home-based symptom management.” (Johnson) “The purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate a community-based palliative care lay health advisor (LHA) intervention for rural-dwelling Latino adults with cancer. Culturally relevant conversations about advance care planning began …” (Larson) |

|

“We developed a suite of videos, booklets, and websites available in English and Spanish, which convey the risks and benefits of common chemotherapy regimens. After revising the English materials, we translated them into Spanish using a multi-step process. The intervention centers upon conversations with 12 Latino patients about their treatment experiences; video clips highlight culturally relevant themes (personalismo, familismo, faith, communication gaps, prognostic information preferences) identified during the third adaptation step…Table 1 describes lowering literacy level.” (Leiter) “Participants were emailed a digital copy or given a hard copy (via mail or in person) of the intervention booklet in their preferred language (English or Spanish)…Major changes were made to the manual based on user feedback and included: making it easier to understand, providing supportive tables and reference materials to understand the medical jargon, simplifying the language and reducing redundancies in content, adding vignettes to give examples of the content in real-world scenarios and make it more applicable to Latinos, adding features around cultural tailoring and inclusion of family members, and providing clear end goal action steps for ACP at the end of the manual.” (Shen) |

References

- Fang, M.L.; Sixsmith, J.; Sinclair, S.; Horst, G. A knowledge synthesis of culturally-and spiritually-sensitive end-of-life care: Findings from a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohr, S.; Jeong, S.; Saul, P. Cultural and religious beliefs and values, and their impact on preferences for end-of-life care among four ethnic groups of community-dwelling older persons. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujanes-Mantor, N.; Buga, S. Cultural Competency models at the end of life. In Understanding End of Life Practices: Perspectives on Communication, Religion and Culture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schweda, M.; Schicktanz, S.; Raz, A.; Silvers, A. Beyond cultural stereotyping: Views on end-of-life decision making among religious and secular persons in the USA, Germany, and Israel. BMC Med. Ethics 2017, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffman, J.L.; Harmer, B. End-of-Life Care. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Von Gunten, C.F.; Lupu, D. Development of a medical subspecialty in palliative medicine: Progress report. J. Palliat. Med. 2004, 7, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudore, R.L.; Lum, H.D.; You, J.J.; Hanson, L.C.; Meier, D.E.; Pantilat, S.Z.; Matlock, D.D.; Rietjens, J.A.; Korfage, I.J.; Ritchie, C.S.; et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, L. Hospice care at the end of life. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2004, 20, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoPresti, M.A.; Dement, F.; Gold, H.T. End-of-life care for people with cancer from ethnic minority groups: A systematic review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2016, 33, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, L.V.; Agarwal, M.; Stone, P.W. Racial/ethnic disparities in nursing home end-of-life care: A systematic review. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Luth, E.A.; Lin, S.Y.; Brody, A.A. Advance care planning, palliative care, and end-of-life care interventions for racial and ethnic underrepresented groups: A systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, e248–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.S. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawed, A.; Comer, A.R. Disparities in end-of-life care for racial minorities: A narrative review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2024, 13, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlovic, M.; Smith, K.; Mossialos, E. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in the United States: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). SSM-Popul. Health 2019, 7, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, L.M.; Walsh, L.E.; Horswell, R.; Miele, L.; Chu, S.; Melancon, B.; Lefante, J.; Blais, C.M.; Rogers, J.L.; Hoerger, M. Racial disparities in end-of-life care between black and white adults with metastatic cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciu, A.; Negussie, Y.; Geller, A.; Weinstein, J.N. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Orlovic, M.; Warraich, H.; Wolf, D.; Mossialos, E. End-of-life planning depends on socio-economic and racial background: Evidence from the US Health and Retirement Study (HRS). J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.A.; Person, S.D.; Gosline, A.; Gawande, A.A.; Block, S.D. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning: Results of a statewide population-based survey. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyakoil, V.S.; Neri, E.; Kraemer, H. No easy talk: A mixed methods study of doctor reported barriers to conducting effective end-of-life conversations with diverse patients. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, S.J.; Yanguela, J.; Odebunmi, O.; Grimshaw, A.A.; Giri, S.; Wheeler, S.B. Systematic review of interventions addressing racial and ethnic disparities in cancer care and health outcomes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, J.; Booth, A.; Cargo, M.; Flemming, K.; Harden, A.; Harris, J.; Garside, R.; Hannes, K.; Pantoja, T.; Thomas, J. Qualitative evidence. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 525–545. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, L.C.; Armstrong, T.D.; Green, M.A.; Hayes, M.; Peacock, S.; Elliot-Bynum, S.; Goldmon, M.V.; Corbie-Smith, G.; Earp, J.A. Circles of care: Development and initial evaluation of a peer support model for African Americans with advanced cancer. Health Educ. Behav. 2013, 40, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, L.C.; Green, M.A.; Hayes, M.; Diehl, S.J.; Warnock, S.; Corbie-Smith, G.; Lin, F.C.; Earp, J.A. Circles of care: Implementation and evaluation of support teams for African Americans with cancer. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monton, O.; Abou-Zamzam, A.; Fuller, S.; Barnes-Malone, T.; Siddiqi, A.; Woods, A.; Patton, J.; Ibe, C.A.; Johnston, F.M. Palliative Care Curriculum and Training Plan for community health workers. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 14, e2972–e2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.J.; Durieux, B.N.; Cannady, K.; Johnson, K.S.; Ford, D.W.; Block, S.D.; Paladino, J.; Sterba, K.R. Acceptability of a Serious Illness Conversation Guide to Black Americans: Results from a focus group and oncology pilot study. Palliat. Support. Care 2023, 21, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekelman, D.B.; Fink, R.M.; Sannes, T.; Kline, D.M.; Borrayo, E.A.; Turvey, C.; Fischer, S.M. Puente para cuidar (bridge to caring): A palliative care patient navigator and counseling intervention to improve distress in Latino/as with advanced cancer. Psycho-oncology 2020, 29, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.M.; Kline, D.M.; Min, S.J.; Okuyama-Sasaki, S.; Fink, R.M. Effect of Apoyo con Cariño (support with caring) trial of a patient navigator intervention to improve palliative care outcomes for Latino adults with advanced cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.A.; Melendez, C.; Larson, K. Using participatory action research to sustain palliative care knowledge and readiness among Latino community leaders. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2022, 39, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.L.; Mathews, H.F.; Melendez, C.R.; Hupp, T.; Estrada, M.; Moye, J.P.; Passwater, C.C.; Muzaffar, M. Can a Palliative Care Lay Health Advisor–Nurse Partnership Improve Health Equity for Latinos with Cancer? AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2023, 123, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, R.E.; Varas, M.T.B.; Miralda, K.; Muneton-Castano, Y.; Furtado, G.; Revette, A.; Cronin, C.; Soares, H.P.; Lopez, A.; Hayman, L.L.; et al. Adaptation of a multimedia chemotherapy educational intervention for Latinos: Letting patient narratives speak for themselves. J. Cancer Educ. 2023, 38, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.J.; Cho, S.; De Los Santos, C.; Yarborough, S.; Maciejewski, P.K.; Prigerson, H.G. Planning for your advance care needs (PLAN): A communication intervention to improve advance care planning among latino patients with advanced cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givler, A.; Bhatt, H.; Maani-Fogelman, P.A. The Importance of Cultural Competence in Pain and Palliative Care. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Monette, E.M. Cultural considerations in palliative care provision: A scoping review of Canadian literature. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2021, 2, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elk, R.; Gazaway, S. Engaging social justice methods to create palliative care programs that reflect the cultural values of African American patients with serious illness and their families: A path towards health equity. J. Law Med. Ethics 2021, 49, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sy, M.; Ritchie, C.S.; Vranceanu, A.M.; Bakhshaie, J. Palliative Care Clinical Trials in Underrepresented Ethnic and Racial Minorities: A Narrative Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2024, 27, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, M.E. Patient engagement in healthcare planning and evaluation: A call for social justice. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2022, 37, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudore, R.L.; Fried, T.R. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: Preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 153, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietjens, J.A.; Sudore, R.L.; Connolly, M.; van Delden, J.J.; Drickamer, M.A.; Droger, M.; van der Heide, A.; Heyland, D.K.; Houttekier, D.; Janssen, D.J.; et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: An international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e543–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.; Bond, C.; Hill, P.S. The power of talk and power in talk: A systematic review of Indigenous narratives of culturally safe healthcare communication. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2018, 24, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedjat-Haiem, F.R.; Carrion, I.V.; Gonzalez, K.; Quintana, A.; Ell, K.; O’Connell, M.; Thompson, B.; Mishra, S.I. Implementing an advance care planning intervention in community settings with older Latinos: A feasibility study. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine; Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End-of-Life Issues. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, K.A.; Büdenbender, B.; Blum, A.K.; Grüne, B.; Kriegmair, M.C.; Michel, M.S.; Alpers, G.W. Power asymmetry and embarrassment in shared decision-making: Predicting participation preference and decisional conflict. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2025, 25, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, D.V.; Feuer, Z.; Ciprut, S.; Lopez, N.M.; Fagerlin, A.; Shedlin, M.; Gold, H.T.; Li, H.; Lynch, G.; Warren, R.; et al. Randomized trial of community health worker-led decision coaching to promote shared decision-making for prostate cancer screening among Black male patients and their providers. Trials 2021, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, L.; Barnes, K.; Somerville, M.; Littlewood, R.; Atkins, H.; Rogany, A.; Williams, L.T. Cultural adaptation of health interventions including a nutrition component in Indigenous peoples: A systematic scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.; Camosso-Stefinovic, J.; Gillies, C.; Shaw, E.J.; Cheater, F.; Flottorp, S.; Robertson, N.; Wensing, M.; Fiander, M.; Eccles, M.P.; et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, J.Y.; Liu, M.F. Culturally tailored interventions for ethnic minorities: A scoping review. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2078–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPetrillo, B.; Adkins-Jackson, P.B.; Yearby, R.; Dixon, C.; Pigott, T.D.; Petteway, R.J.; LaBoy, A.; Petiwala, A.; Leonard, M. Characteristics of interventions that address racism in the United States and opportunities to integrate equity principles: A scoping review. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Age | Population Location | Minority Group | Setting of the Study | Education | Income | Specific Type | Advanced Cancer? | Language | Intervention Types | What Was Tailored for? | Challenges | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanson et al. 2013 | 2%: <21, 2%: 21–30, 4%: 31–40, 19%: 41–50, 21%: 51–60, 17%: 61–70, 28%: >71, 6%: not disclosed | Central North Carolina | 98%: Black, 2%: Hispanic | Community settings | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Exclusively Advanced Cancer Patients | English Only | Training Programs for Health Workers and Community Leaders | Trust and Faith-based Values | Cultural and Trust Issues, Resource Constraints | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication, Improved Patient Satisfaction and Trust in Care |

| Hanson et al. 2014 | 13%: <41, 13%: 41–50, 38%: 51–60, 38%: >61 | North Carolina | African American | Academic medical center and affiliated hospice program | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Mostly (64%) Advanced Cancer Patients | English Only | Navigation and Support Programs for Patients and Caregivers | Trust and Faith-based Values | Cultural and Trust Issues, Resource Constraints | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication |

| Monton et al. 2023 | Not specified | Maryland and Alabama | African American | Johns Hopkins Hospital, TidalHealth Peninsula Regional and University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Exclusively Advanced Cancer Patients | English Only | Training Programs for Health Workers and Community Leaders | Trust and Faith-based Values | Recruitment and Retention | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication |

| Sanders et al. 2023 | Mean age = 71 years (range 50–88) | Charleston, South Carolina | African American | Church-based and community volunteer settings, including home visits | 39%: <HS, 26%: HS, 17%: some college, 17%: college graduate | 65%: <10k, 13%: 10–20k, 4%: 20–40k, 4%: 60–70k, 4%: >75k | Lung (9%), GU (13%), GYN (30%), GI (22%), Glioblastoma (4%), Other (22%) | Exclusively Advanced Cancer Patients | English Only | Communication Skills Programs for Patients, Caregivers, Researchers, and Clinicians | Literacy and Faith-based Values | Cultural and Trust Issues, Resource Constraints | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication |

| Bekelman et al. 2020 | Mean: 58 years (SD ± 13) | Rural Eastern Colorado | Latinx | Safety-net clinics, community cancer clinics, National Cancer Institute, and home visits | 36%: <HS | 50%: <15k, 50%: >15k | Breast (16%), GI (21%), GU (21%), Lung (21%), Other (21%) | Exclusively Advanced Cancer Patients | Bilingual (English/Spanish) | Navigation and Support Programs for Patients and Caregivers | Language, Literacy, and Cultural Values | Resource Constraints | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication, Improved ACP Engagement, Improved Patient Satisfaction and Trust in Care |

| Fischer et al. 2018 | Mean: 58.1 years (SD ± 13.6) | Rural Eastern Colorado | Latinx | Safety-net clinics, community cancer clinics, National Cancer Institute, and home visits | 50.2%: <HS | 53.6%:<15k, 88.2%: Unemployed | Breast (19.3%), GI (33.6%), GU (11.7%), GYN (10.3%), Lung (9.0%), Hematologic (7.6%), Other (8.5%) | Exclusively Advanced Cancer Patients | Bilingual (English/Spanish) | Navigation and Support Programs for Patients and Caregivers | Language, Literacy, and Cultural Values | Resource Constraints | Improved ACP Engagement, Improved Patient Satisfaction and Trust in Care |

| Johnson et al. 2022 | Mean: 41.2 years (SD ± 13.3) | Rural North Carolina | Latinx | Over the phone, location not specified | 40%: HS | 73%: Worked full time | Not specified | Exclusively Advanced Cancer Patients | Bilingual (English/Spanish) | Training Programs for Health Workers and Community Leaders | Language, Literacy, and Cultural Values | Resource Constraints | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication, Improved Patient Satisfaction and Trust in Care |

| Larson et al. 2023 | Patients: Mean age = 51 years (SD ± 14) | North Carolina | Latinx | Regional cancer centers in Eastern North Carolina | 71.4%: <HS, 14.3%: HS, 14.3%: >HS | 85.7%: Unemployed, 14.3%: Employed, specified as low income | Breast (28.6%), Hematological (25.7%), GI (20%), GU/GYN (14.3%), Lung (5.7%), Head and Neck (5.7%) | Exclusively Advanced Cancer Patients | Bilingual (English/Spanish) | Training Programs for Health Workers and Community Leaders | Language, Literacy, and Cultural Values | Resource Constraints | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication, Improved ACP Engagement |

| Leiter et al. 2023 | Older Adult patients | Massachusetts | Latinx | Clinical settings - Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Boston Medical Center | Not specified | Not specified | All GI | Exclusively Advanced Cancer Patients | Bilingual (English/Spanish) | Education Programs for Patients that are Culturally Tailored | Language, Literacy, and Cultural Values | Resource Constraints | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication |

| Shen et al. 2023 | Mean Patient age = 53.4 years (SD ± 17.5) | Northeast academic medical center in an urban setting | Latinx | Intervention completed at home | 54.5%: <HS, 18.2%: Some College, 27.3%: College or more | 45.4%: <40k, 27.3%: >40k, 27.3%: did not disclose | Not specified | Exclusively Advanced Cancer Patients | Bilingual (English/Spanish) | Communication Skills Programs for Patients, Caregivers, Researchers, and Clinicians | Language, Literacy, and Cultural Values | Language and Health Literacy Barriers, Resource Constraints | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication, Improved ACP Engagement, Improved Patient Satisfaction and Trust in Care |

| Racial Group & Studies (n) | Intervention Categories | Intervention Tailoring | Implementation Challenges | Intervention Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American/ Black Populations Hanson 2013, Hanson 2014, Monton, Sanders (4) | Communication Skills Programs for Patients, Caregivers, Researchers, and Clinicians (Sanders) Education Programs for Patients that are Culturally Tailored (None) Navigation and Support Programs for Patients and Caregivers (Hanson 2014) Training Programs for Health Workers and Community Leaders (Hanson 2013, Monton) | Trust and Faith-based Values (Hanson 2013, Hanson 2014, Monton) Literacy and Faith-based Values (Sanders) Language, Literacy, and Cultural Values (None) | Cultural and Trust Issues (Hanson 2013, Hanson 2014, Sanders) Resource Constraints (Hanson 2013, Hanson 2014, Sanders) Recruitment and Retention (Monton) Language and Literacy Barriers (None) | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication (Hanson 2013, Hanson 2014, Monton, Sanders) Improved ACP Engagement (None) Improved Patient Satisfaction and Trust in Care (Hanson 2013) |

| Latino/Latinx Populations Bekelman, Fischer, Johnson, Larson, Leiter, Shen (6) | Communication Skills Programs for Patients, Caregivers, Researchers, and Clinicians (Shen) Education Programs for Patients that are Culturally Tailored (Leiter) Navigation and Support Programs for Patients and Caregivers (Bekelman, Fischer) Training Programs for Health Workers and Community Leaders (Johnson, Larson) | Trust and Faith-based Values (None) Literacy and Faith-based Values (None) Language, Literacy, and Cultural Values (Bekelman, Fischer, Johnson, Larson, Leiter, Shen) | Cultural and Trust Issues (None) Resource Constraints (Bekelman, Fischer, Johnson, Larson, Leiter, Shen) Recruitment and Retention (None) Language and Literacy Barriers (Shen) | Improved Palliative Care Knowledge and Communication (Bekelman, Johnson, Larson, Leiter, Shen) Improved ACP Engagement (Bekelman, Fischer, Larson, Shen) Improved Patient Satisfaction and Trust in Care (Bekelman, Fischer, Johnson, Shen) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yee, C.J.; Penumudi, A.; Lewinson, T.; Khayal, I.S. End-of-Life Cancer Care Interventions for Racially and Ethnically Diverse Populations in the USA: A Scoping Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 2209. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132209

Yee CJ, Penumudi A, Lewinson T, Khayal IS. End-of-Life Cancer Care Interventions for Racially and Ethnically Diverse Populations in the USA: A Scoping Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(13):2209. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132209

Chicago/Turabian StyleYee, Carolyn J., Aashritha Penumudi, Terri Lewinson, and Inas S. Khayal. 2025. "End-of-Life Cancer Care Interventions for Racially and Ethnically Diverse Populations in the USA: A Scoping Review" Cancers 17, no. 13: 2209. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132209

APA StyleYee, C. J., Penumudi, A., Lewinson, T., & Khayal, I. S. (2025). End-of-Life Cancer Care Interventions for Racially and Ethnically Diverse Populations in the USA: A Scoping Review. Cancers, 17(13), 2209. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132209