Reasons for and Congruence Between Preferred and Actual Place of Death Among Cancer Patients Receiving End-of-Life Care: A Cross-Cultural Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study in East Asia

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

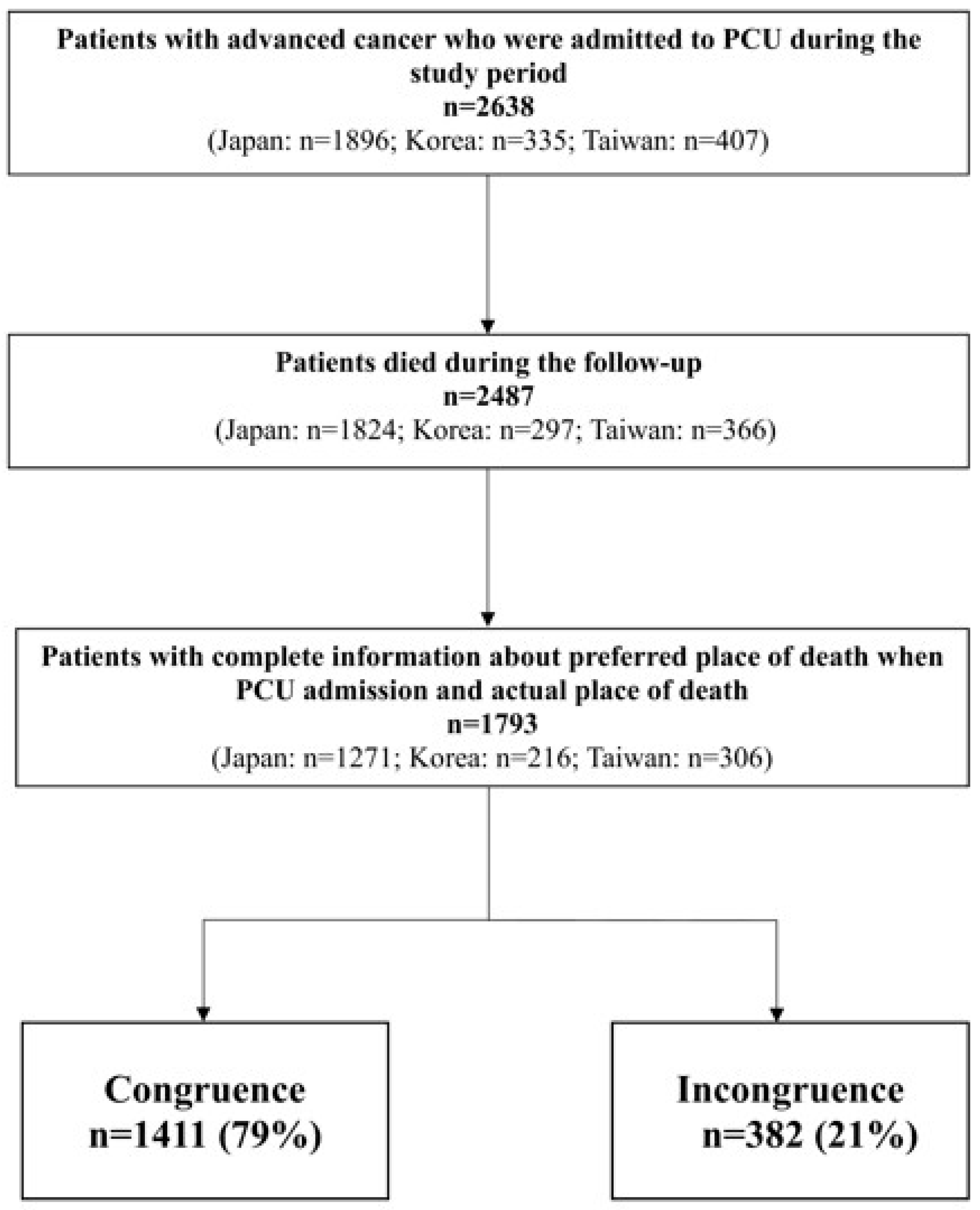

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Preferred and Actual POD

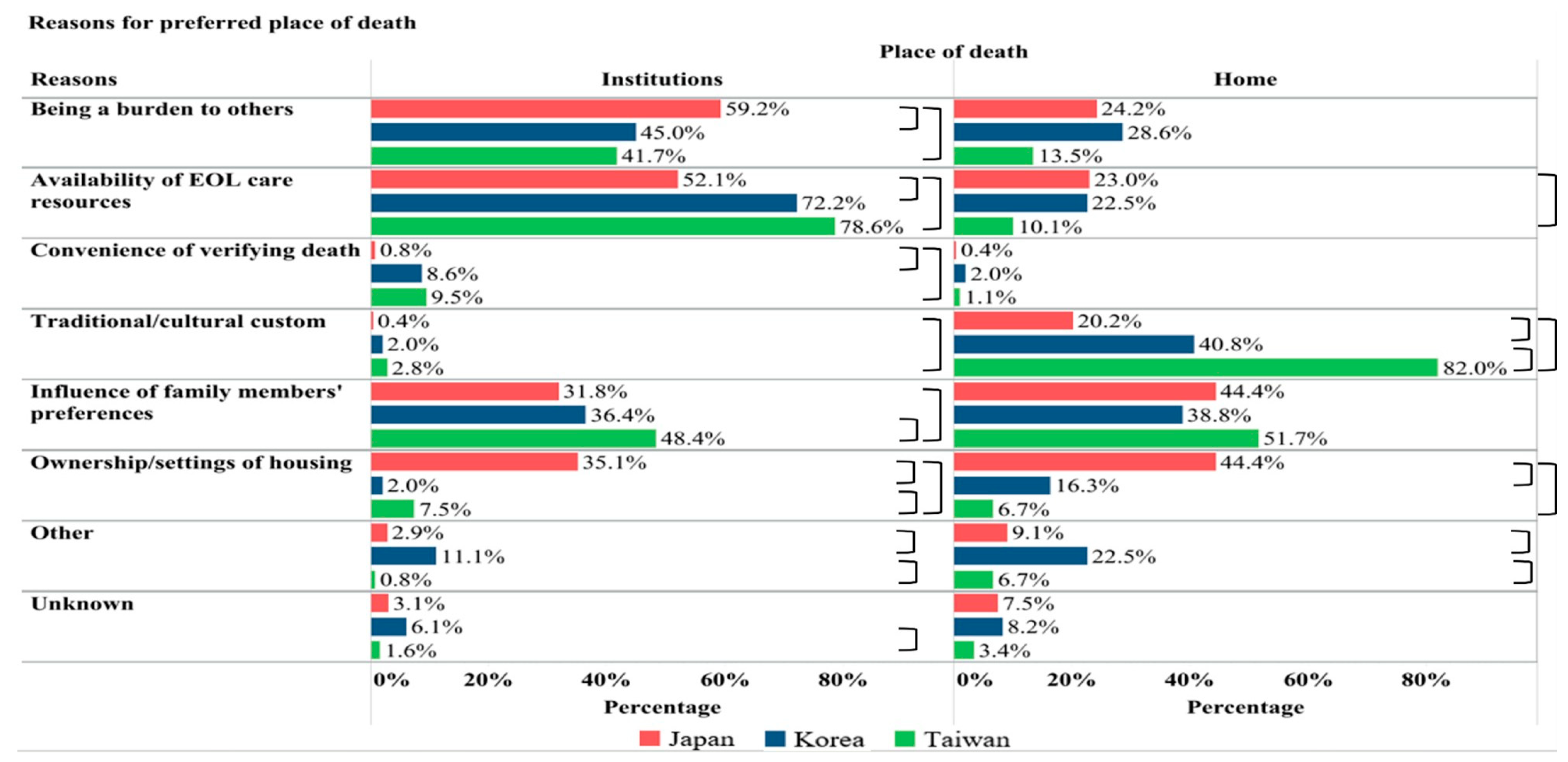

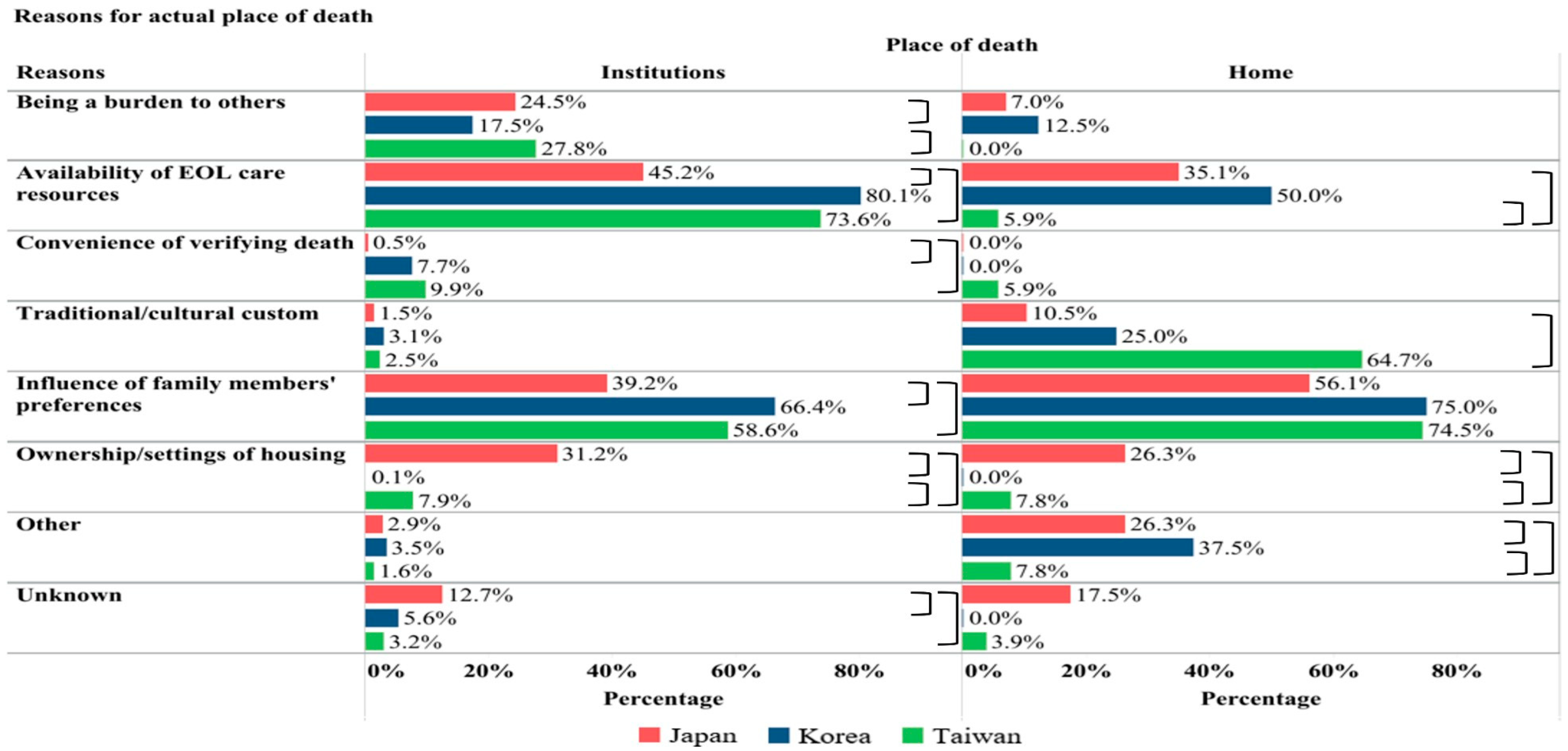

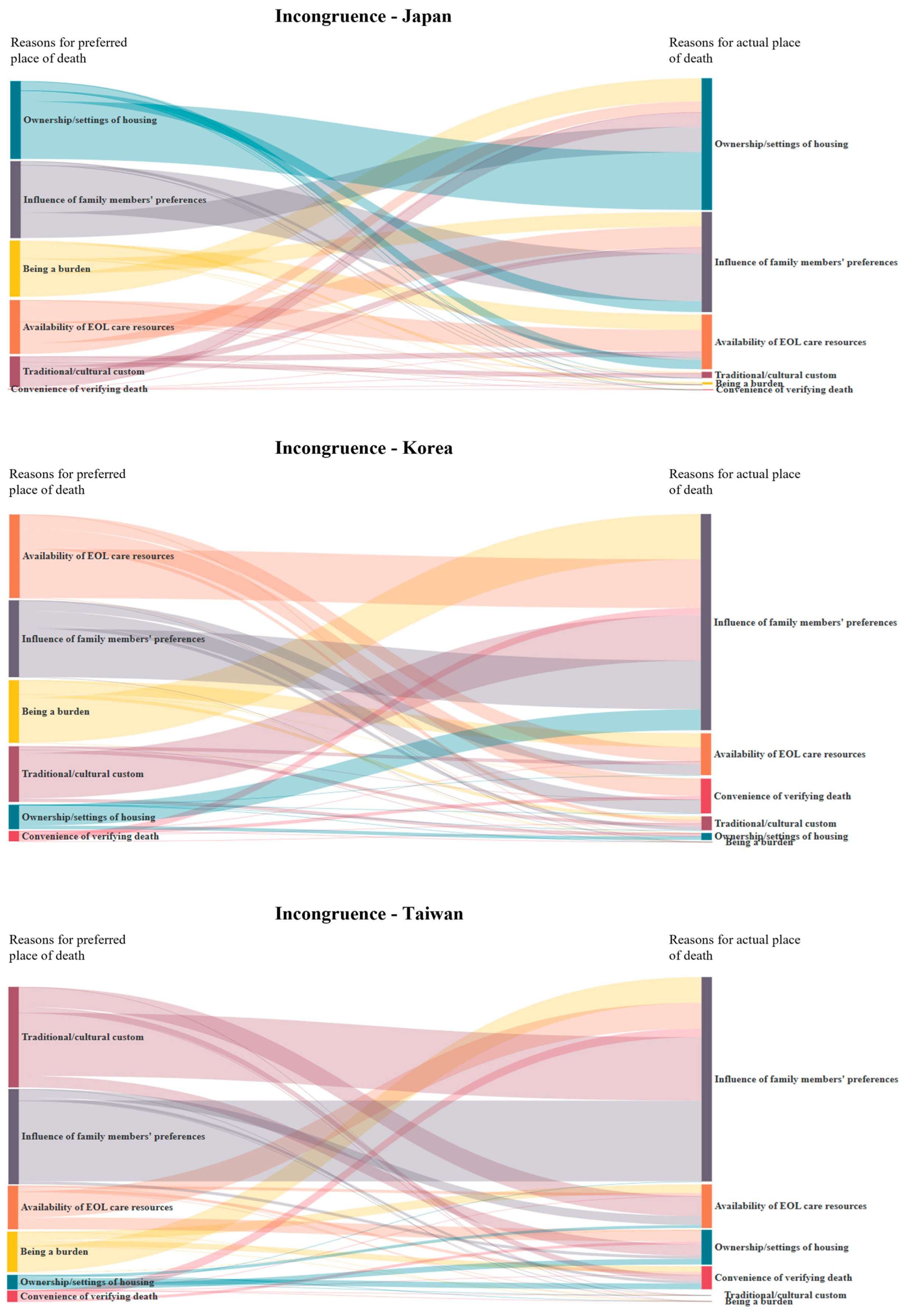

3.3. Reasons for and Congruence of POD

4. Discussion

4.1. POD Congruence and Its Reasons

4.2. Reasons for Preferred and Actual POD

4.3. Preferred POD at Different Stages in Disease Trajectory

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hales, S.; Chiu, A.; Husain, A.; Braun, M.; Rydall, A.; Gagliese, L.; Zimmermann, C.; Rodin, G. The Quality of Dying and Death in Cancer and Its Relationship to Palliative Care and Place of Death. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey, L.; Curtis, J.R.; Lafferty, W.E.; Herting, J.R.; Engelberg, R.A. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): Empirical Domains and Theoretical Perspectives. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010, 39, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainsford, S.; Phillips, C.B.; Glasgow, N.J.; MacLeod, R.D.; Wiles, R.B. The ‘safe death’: An ethnographic study exploring the perspectives of rural palliative care patients and family caregivers. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higginson, I.J.; Daveson, B.A.; Morrison, R.S.; Yi, D.; Meier, D.; Smith, M.; Ryan, K.; McQuillan, R.; Johnston, B.M.; Normand, C.; et al. Social and clinical determinants of preferences and their achievement at the end of life: Prospective cohort study of older adults receiving palliative care in three countries. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.; Miccinesi, G.; Beccaro, M.; Moreels, S.; Donker, G.A.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.; Alonso, T.V.; Deliens, L.; Block, L.V.D. Factors Associated with Fulfilling the Preference for Dying at Home among Cancer Patients: The role of General Practitioners. J. Palliat. Care 2014, 30, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.; Higginson, I.J.; Calanzani, N.; Cohen, J.; Deliens, L.; Daveson, B.A.; Bechinger-English, D.; Bausewein, C.; Ferreira, P.L.; Toscani, F.; et al. Preferences for place of death if faced with advanced cancer: A population survey in England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2006–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Cheng, W.; Cheng, M.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Z. The Preference of Place of Death and its Predictors Among Terminally Ill Patients With Cancer and Their Caregivers in China. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2015, 32, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, A.; Morita, T.; Miyashita, M.; Yoshida, S.; Akizuki, N.; Shirahige, Y.; Akiyama, M.; Eguchi, K. Preferred place of care and place of death of the general public and cancer patients in Japan. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 2575–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.S.; Chae, Y.M.; Lee, C.G.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-W.; Heo, D.S.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, K.S.; Hong, Y.S.; Yun, Y.H. Factors influencing preferences for place of terminal care and of death among cancer patients and their families in Korea. Support. Care Cancer 2005, 13, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.T.; Chen, C.C.-H.; Tang, W.-R.; Liu, T.-W. Determinants of Patient-Family Caregiver Congruence on Preferred Place of Death in Taiwan. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010, 40, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-L.; Yao, C.-A.; Hu, W.-Y.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Hwang, S.-J.; Chen, C.-D.; Lin, W.-Y.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chiu, T.-Y. Prevailing Ethical Dilemmas Encountered by Physicians in Terminal Cancer Care Changed After the Enactment of the Natural Death Act: 15 Years’ Follow-up Survey. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, T.R.; Byers, A.L.; Gallo, W.T.; Van Ness, P.H.; Towle, V.R.; O’leary, J.R.; Dubin, J.A. Prospective Study of Health Status PREFERENCES and Changes in PREFERENCES Over Time in Older Adults. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straton, J.B.; Wang, N.-Y.; Meoni, L.A.; Ford, D.E.; Klag, M.J.; Casarett, D.; Gallo, J.J. Physical functioning, depression, and preferences for treatment at the end of life: The Johns Hopkins Pre-cursors Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorne, I.; van Rijn, M.; Dofferhoff, S.M.; Willems, D.L.; Buurman, B.M. Patients’ preferred place of death: Patients are willing to consider their preferences, but someone has to ask them. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 2004–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginson, I.J.; Hall, S.; Koffman, J.; Riley, J.; Gomes, B. Time to get it right: Are preferences for place of death more stable than we think? Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 352–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Prat, A.; Monforte-Royo, C.; Porta-Sales, J.; Escribano, X.; Balaguer, A. Patient Perspectives of Dignity, Autonomy and Control at the End of Life: Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, E.; Selman, L.E. Cultural Factors Influencing Advance Care Planning in Progressive, Incurable Disease: A Systematic Review With Narrative Synthesis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, 613–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprung, C.L.; Jennerich, A.L.; Joynt, G.M.; Michalsen, A.; Curtis, J.R.; Efferen, L.S.; Leonard, S.; Metnitz, B.; Mikstacki, A.; Patil, N.; et al. The Influence of Geography, Religion, Religiosity and Institutional Factors on Worldwide End-of-Life Care for the Critically Ill: The WELPICUS Study. J. Palliat. Care 2021, 39, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Sanjuán, S.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Clement-Carbonell, V.; Campos-Calderón, C.P.; Orts-Beneito, N.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J. Levels and Determinants of Place-Of-Death Congruence in Palliative Patients: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 807869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, R.; Roman, E.; Smith, A.G.; Turner, A.; Garry, A.C.; Patmore, R.; Howard, M.R.; A Howell, D. Preferred and actual place of death in haematological malignancies: A report from the UK haematological malignancy research network. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 11, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Capel, M.; Jones, G.; Gazi, T. The importance of identifying preferred place of death. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 9, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijmakers, N.J.; de Veer, A.J.; Zwaan, R.; Hofstede, J.M.; Francke, A.L. Which patients die in their preferred place? A secondary analysis of questionnaire data from bereaved relatives. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogaard, T.; Neergaard, M.A.; Sokolowski, I.; Olesen, F.; Jensen, A.B. Congruence between preferred and actual place of care and death among Danish cancer patients. Palliat. Med. 2012, 27, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzon, L.C.E.; Claus, M.; Zepf, K.I.; Letzel, S.; Fischbeck, S.; Weber, M. Preference for Place of Death in Germany. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-Y.; Suh, S.-Y.; Morita, T.; Oyama, Y.; Chiu, T.-Y.; Koh, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Hwang, S.-J.; Yoshie, T.; Tsuneto, S. A Cross-Cultural Study on Behaviors When Death Is Approaching in East Asian Countries: What Are the Physician-Perceived Common Beliefs and Practices? Medicine 2015, 94, e1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.; Higginson, I.J. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: Systematic review. BMJ 2006, 332, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, P.; Street, D.J.; Hall, J.; Agar, M.; Phillips, J. Valuing End-of-Life Care for Older People with Advanced Cancer: Is Dying at Home Important? Patient 2021, 14, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannon, F.; Cairnduff, V.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Blaney, J.; Gomes, B.; Gavin, A.; Donnelly, C. Insights into the factors associated with achieving the preference of home death in terminal cancer: A national population-based study. Palliat. Support. Care 2018, 16, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhang, L.; Guerriere, D.; Coyte, P.C. Congruence between Preferred and Actual Place of Death for Those in Receipt of Home-Based Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.-L.; Lin, H.-R.; Wang, J.-H.; Hsieh, J.-G.; Wang, Y.-W. The Hospice Information System and its association with the congruence between the preferred and actual place of death. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2017, 29, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolasco, A.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Pereyra-Zamora, P.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J.; Copete, J.M.; Oliva-Arocas, A.; Cabrero-García, J. Socioeconomic inequalities in the place of death in urban small areas of three Mediterranean cities. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.; Lin, C.-P.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Suh, S.-Y.; Takenouchi, S.; Ng, R.; Chan, H.; Kim, S.-H.; Chen, P.-J.; Yuen, K.K.; et al. Communication in Cancer Care in Asia: A Narrative Review. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2023, 9, e2200266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Fukui, S.; Saito, T.; Fujita, J.; Watanabe, M.; Yoshiuchi, K. Family Preference for Place of Death Mediates the Relationship between Patient Preference and Actual Place of Death: A Nationwide Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, S.; Otsuki, N.; Ikezaki, S.; Fukahori, H.; Irie, S. Provision and related factors of end-of-life care in elderly housing with care services in collaboration with home-visiting nurse agencies: A nationwide survey. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, C.-Y.; Hu, W.-Y.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Yao, C.-A.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chiu, T.-Y. Patient Preferences versus Family Physicians’ Perceptions Regarding the Place of End-of-Life Care and Death: A Nationwide Study in Taiwan. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausewein, C.; Calanzani, N.; A Daveson, B.; Simon, S.T.; Ferreira, P.L.; Higginson, I.J.; Bechinger-English, D.; Deliens, L.; Gysels, M.; Toscani, F.; et al. ‘Burden to others’ as a public concern in advanced cancer: A comparative survey in seven European countries. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathiananthan, M.K.; Crawford, G.B.; Eliott, J. Healthcare professionals’ perspectives of patient and family preferences of patient place of death: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.T. Meanings of dying at home for Chinese patients in Taiwan with terminal cancer: A literature review. Cancer Nurs. 2000, 23, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.; Calanzani, N.; Koffman, J.; Higginson, I.J. Is dying in hospital better than home in incurable cancer and what factors influence this? A population-based study. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Maeda, I.; Hatano, Y.; Suh, S.-Y.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Kim, S.H.; Chen, P.-J.; Morita, T.; Tsuneto, S.; Mori, M. Communication and Behavior of Palliative Care Physicians of Patients With Cancer Near End of Life in Three East Asian Countries. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 315–322.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Japan n = 1896 | Korea n = 335 | Taiwan n = 407 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age a [years, mean ± SD] | 72.4 ± 12.3 | 68.3 ± 12.2 | 66.6 ± 13.8 | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.1295 | |||

| Male | 965 (50.9) | 184 (54.9) | 226 (55.5) | |

| Female | 931 (49.1) | 151 (45.1) | 181 (44.5) | |

| Primary cancer site, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Lung | 319 (16.8) | 49 (14.6) | 77 (18.9) | |

| Gastroesophageal | 265 (14.0) | 45 (13.4) | 28 (6.9) | |

| Colorectal | 254 (13.4) | 52 (15.5) | 56 (13.8) | |

| Hepatobiliary/Pancreas | 363 (19.1) | 96 (28.7) | 99 (24.3) | |

| Breast | 131 (6.9) | 19 (5.7) | 18 (4.4) | |

| Gynecological | 119 (6.3) | 15 (4.5) | 17 (4.2) | |

| Urological | 141 (7.4) | 16 (4.8) | 27 (6.6) | |

| Head/Neck | 68 (3.6) | 8 (2.4) | 48 (11.8) | |

| Others | 236 (12.4) | 35 (10.4) | 37 (9.1) | |

| Highest level of education b, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| <High school | 58 (3.1) | 157 (46.9) | 224 (55.0) | |

| High school/Some college | 184 (10) | 118 (35.2) | 133 (32.7) | |

| ≥College degree | 127 (6.7) | 49 (14.6) | 43 (10.6) | |

| Living with family c, n (%) | 1376 (72.8) | 293 (87.5) | 375 (92.1) | <0.001 |

| Marital status d, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 1151 (60.7) | 227 (67.8) | 250 (61.4) | |

| Widowed | 403 (21.3) | 67 (20.0) | 89 (21.9) | |

| Unmarried | 205 (10.8) | 13 (3.9) | 29 (7.1) | |

| Separated | 113 (6.0) | 26 (7.8) | 39 (9.6) | |

| Religion, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No religion | 822 (43.4) | 121 (36.1) | 60 (14.7) | |

| Buddhism and Taoism | 206 (10.9) | 75 (22.4) | 225 (55.3) | |

| Christianity | 38 (2.0) | 133 (39.7) | 24 (5.9) | |

| Others or unknown | 830 (43.8) | 6 (1.8) | 98 (24.1) | |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0–2 | 184 (9.7) | 89 (26.6) | 41 (10.1) | |

| 3 | 797 (42.0) | 158 (47.2) | 123 (30.2) | |

| 4 | 915 (48.3) | 88 (26.3) | 243 (59.7) | |

| Communication capacity at admission e, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 980 (51.7) | 175 (52.2) | 156 (38.3) | |

| 1 | 520 (27.4) | 115 (34.3) | 121 (29.7) | |

| 2 | 211 (11.1) | 20 (6.0) | 58 (14.3) | |

| 3 | 185 (9.8) | 23 (6.9) | 72 (17.7) | |

| Length of stay (days) f | 26.9 | 25.9 | 14.3 | <0.001 |

| Preferred Place of Death * | Actual Place of Death # | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan n = 1896 | Korea n = 335 | Taiwan n = 407 | Japan n = 1824 | Korea n = 297 | Taiwan n = 366 | |

| Place of death, n (%) | ||||||

| PCU/hospice | 1045 (55.1) | 170 (50.7) | 245 (60.2) | 1746 (95.7) | 279 (94.0) | 300 (82.0) |

| General ward | 26 (1.37) | 28 (8.4) | 7 (1.7) | 19 (1.0) | 5 (1.7) | 10 (2.7) |

| Own home | 244 (12.9) | 49 (14.6) | 88 (21.6) | 55 (3.0) | 5 (1.7) | 50 (13.7) |

| Care/nursing home | 7 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Home of a relative/friend | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.1) |

| Unknown/No preference | 570 (30.1) | 87 (26.0) | 65 (16.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, C.-H.; Wu, C.-Y.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Mori, M.; Suh, S.-Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Lin, W.-Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Huang, H.-L.; Hamano, J.; et al. Reasons for and Congruence Between Preferred and Actual Place of Death Among Cancer Patients Receiving End-of-Life Care: A Cross-Cultural Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study in East Asia. Cancers 2025, 17, 2062. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132062

Yang C-H, Wu C-Y, Cheng S-Y, Mori M, Suh S-Y, Kim S-H, Lin W-Y, Yamaguchi T, Huang H-L, Hamano J, et al. Reasons for and Congruence Between Preferred and Actual Place of Death Among Cancer Patients Receiving End-of-Life Care: A Cross-Cultural Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study in East Asia. Cancers. 2025; 17(13):2062. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132062

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Chiu-Hsien, Chien-Yi Wu, Shao-Yi Cheng, Masanori Mori, Sang-Yeon Suh, Sun-Hyun Kim, Wen-Yuan Lin, Takashi Yamaguchi, Hsien-Liang Huang, Jun Hamano, and et al. 2025. "Reasons for and Congruence Between Preferred and Actual Place of Death Among Cancer Patients Receiving End-of-Life Care: A Cross-Cultural Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study in East Asia" Cancers 17, no. 13: 2062. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132062

APA StyleYang, C.-H., Wu, C.-Y., Cheng, S.-Y., Mori, M., Suh, S.-Y., Kim, S.-H., Lin, W.-Y., Yamaguchi, T., Huang, H.-L., Hamano, J., Hiratsuka, Y., Tsuneto, S., Morita, T., Chen, P.-J., & on behalf of the EASED Investigators. (2025). Reasons for and Congruence Between Preferred and Actual Place of Death Among Cancer Patients Receiving End-of-Life Care: A Cross-Cultural Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study in East Asia. Cancers, 17(13), 2062. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132062