Prospective Evaluation of the Influence of Chemoradiotherapy and Stoma on Functional and Symptomatic Outcomes in Rectal Cancer Patients

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

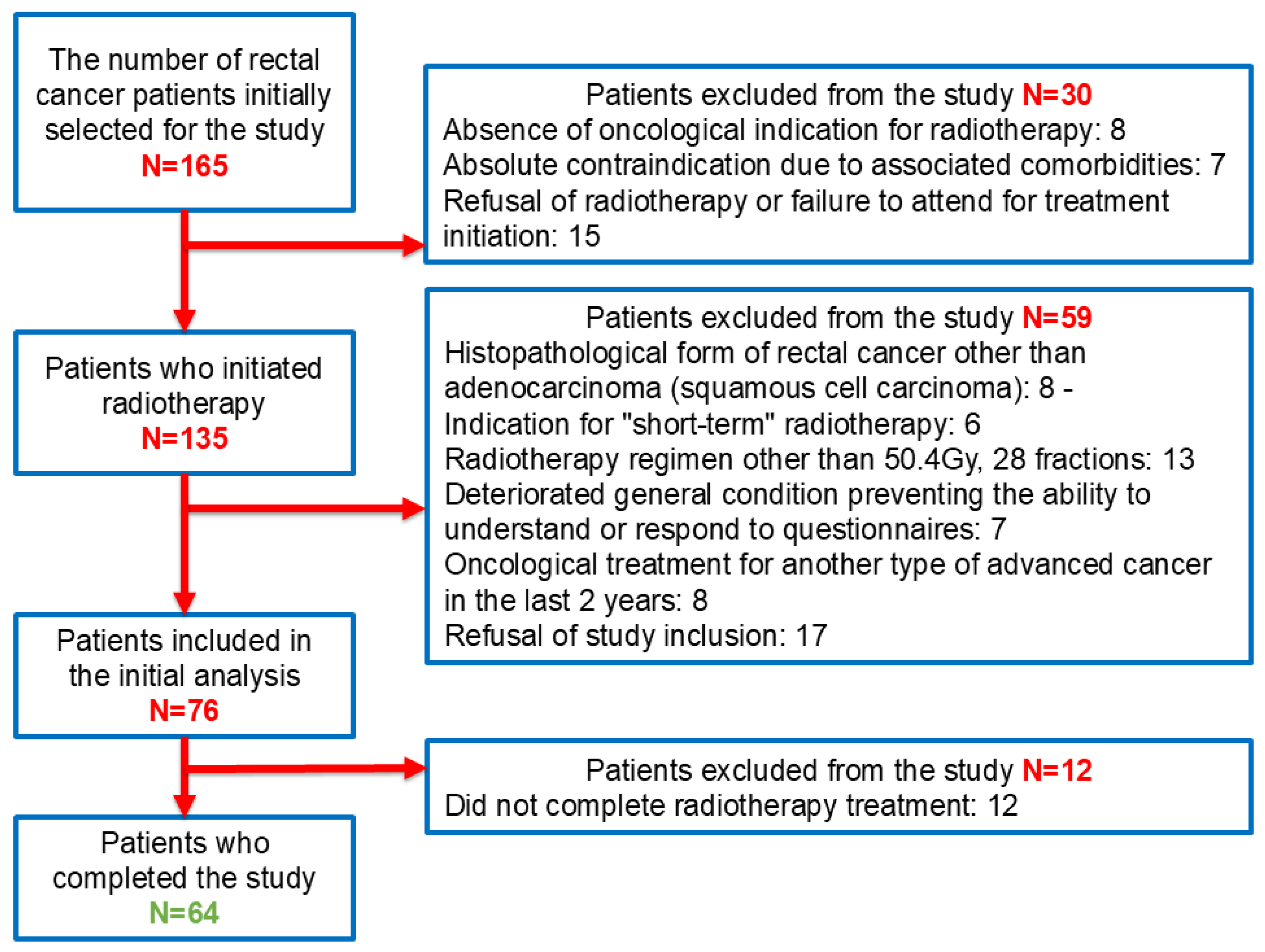

2.1. Patient Selection and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Questionnaire Administration Methodology

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M.; Moreira, D.N.; Ghidini, M. Colon and rectal cancer: An emergent public health problem. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2022: Cancer Fact Sheets—Colorectal Cancer. IARC. 2022. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Soerjomataram, I. The evolving global burden of colorectal cancer: Global patterns and risk factors. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 2558–2573. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar Junior, S.; Oliveira, M.M.; Silva, D.R.M.E.; Mello, C.A.L.; Calsavara, V.F.; Curado, M.P. Survival of patients with colorectal cancer in a cancer center. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2020, 57, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Huh, J.W.; Lee, W.Y.; Yun, S.H.; Kim, H.C.; Cho, Y.B.; Park, Y.; Shin, J.K. Predicting survival in locally advanced rectal cancer with effective chemoradiotherapy response. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tersteeg, J.J.C.; van Esch, L.M.; Gobardhan, P.D.; Kint, P.A.M.; Rozema, T.; Crolla, R.M.P.H.; Schreinemakers, J.M.J. Early local recurrence and one-year mortality of rectal cancer after restricting the neoadjuvant therapy regime. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baidoun, F.; Elshiwy, K.; Elkeraie, Y.; Merjaneh, Z.; Khoudari, G.; Sarmini, M.T.; Gad, M.; Al-Husseini, M.; Saad, A. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: Recent trends and impact on outcomes. Curr. Drug Targets 2021, 22, 998–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Keum, N.; Giovannucci, E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: Emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 713–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Lynch, B.; Aitken, J.; Leggett, B.; Pakenham, K.; Newman, B. Quality of life and colorectal cancer: A review. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2003, 27, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, A.J.; Rashid, A.; Shim, J.S.C.; West, J.; Humes, D.J.; Grainge, M.J. Long-term adverse effects and healthcare burden of rectal cancer radiotherapy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZ J. Surg. 2023, 93, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynne-Jones, R.; Hall, M. Radiotherapy and locally advanced rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 1443–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, N. Management of rectal cancer. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 100, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, D.S.; Berho, M.; Perez, R.O.; Wexner, S.D.; Chand, M. The multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeken, J.C.; Wiestler, B.; Combs, S.E. Image-guided radiooncology: The potential of radiomics in clinical application. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2020, 216, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Minniti, G.; Goldsmith, C.; Brada, M. Radiotherapy. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2012, 104, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Svensson, H.; Möller, T.R.; SBU Survey Group. Developments in radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2003, 42, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.; Soon, Y.Y.; Vellayappan, B.; Ho, F.; Tey, J. Radiation therapy for rectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019, 10, 1238–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisson, E.; Piton, L.; Durand, B.; Sarrade, T.; Huguet, F. Palliative pelvic radiotherapy for symptomatic frail or metastatic patients with rectal adenocarcinoma: A systematic review. Dig. Liver Dis. 2025, 57, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercek, A.; Goodman, K.A.; Hajj, C.; Weisberger, E.; Segal, N.H.; Reidy-Lagunes, D.L.; Stadler, Z.K.; Wu, A.J.; Weiser, M.R.; Paty, P.B. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy first, followed by chemoradiation and then surgery, in the management of locally advanced rectal cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2014, 12, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovina, S.; Youssef, F.; Roy, A.; Hall, W.A.; Sussman, J.J.; DeWees, T.; Myerson, R.J.; Parikh, P.J. Improved metastasis- and disease-free survival with preoperative sequential short-course radiation therapy and FOLFOX chemotherapy for rectal cancer compared with neoadjuvant long-course chemoradiotherapy: Results of a matched pair analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 99, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachet, J.B.; Benoist, S.; Mas, L.; Huguet, F. Traitement néoadjuvant des cancers du rectum [Neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer]. Bull. Cancer 2021, 108, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofheinz, R.D.; Wenz, F.; Post, S.; Matzdorff, A.; Laechelt, S.; Hartmann, J.T.; Müller, L.; Link, H.; Moehler, M.; Kettner, E.; et al. Chemoradiotherapy with capecitabine versus fluorouracil for locally advanced rectal cancer: A randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossum, C.C.; Alabbad, J.Y.; Romak, L.B.; DeWees, T.A.; Parikh, P.J.; Grigsby, P.W. The role of neoadjuvant radiotherapy for locally-advanced rectal cancer with resectable synchronous metastasis. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 8, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, K.L.; Rava, P.S.; DiPetrillo, T.A. The role of local radiation therapy in the treatment of metastatic rectal cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 84, S347. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, D.; Lu, J.; Zheng, H.; Bui, C.; Lin, J.; Kelly, M.; Lim, J. Efficacy of palliative radiation therapy for symptomatic rectal cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2016, 121, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, M.G.; Kersten, C.; Vistad, I.; Bjerre, L.M.; Fosså, S.D.; Guren, M.G. Palliative pelvic radiotherapy for symptomatic rectal cancer—A prospective multicenter study. Acta Oncol. 2016, 55, 1400–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, V.; Deodato, F.; Guido, A.; Macchia, G.; Cilla, S.; Digesù, C.; Ippolito, E.; Valentini, V.; Cellini, N. Palliative short-course radiation therapy in rectal cancer: A phase 2 study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016, 95, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guren, M.G.; Fosså, S.D.; Frykholm, G.; Albertsson, M.; Påhlman, L.; Glimelius, B. The impact of late side effects from pelvic radiotherapy on quality of life in long-term survivors of rectal cancer. Cancer 2019, 125, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, F.; Palombaro, M.; Caravatta, L.; Maranzano, E.; De Felice, F.; Macchia, G. Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer: Role of psychosocial and treatment-related factors. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 7437–7447. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.H.; Efron, J.E.; Berho, M.; Wexner, S.D. The impact of a permanent stoma on quality of life in patients with rectal cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2021, 64, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Croese, A.D.; Lonie, J.M.; Trollope, A.F.; Vather, R.; Pandanaboyana, S.; Samuel, M.; Ma, Y.; Stewart, P. The influence of preoperative stoma education on quality of life outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 24, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Dilalla, V.; Chaput, G.; Williams, T.; Sultanem, K. Radiotherapy side effects: Integrating a survivorship clinical lens to better serve patients. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, M.; Streppel, R.; Hauser, S.; Abramian, A.; Kaiser, C.; Gonzalez-Carmona, M.; Feldmann, G.; Schäfer, N.; Koob, S.; Banat, M.; et al. Impact of patient nationality on the severity of early side effects after radiotherapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 5573–5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutta, B.S.; Fatima, R.; Aziz, M. Radiation enteritis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Loge, L.; Florescu, C.; Alves, A.; Menahem, B. Radiation enteritis: Diagnostic and therapeutic issues. J. Visc. Surg. 2020, 157, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso-João, D.; Pacheco-Figueiredo, L.; Antunes-Lopes, T.; Morgado, L.A.; Azevedo, V.; Vendeira, L.; Silva, J.; Martins-Silva, C. Cumulative incidence and predictive factors of radiation cystitis in patients with localized prostate cancer. Actas Urol. Esp. 2018, 42, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer Puchol, M.D.; Borrel Palanca, A.; Gil Romero, J.; Pallardo Calatayud, Y.; Cervera de Val, V.; Laso Pablos, M.S.; Nogues Pelayo, E. Hematuria grave debida a cistitis rádica. Embolización percutánea selectiva como alternative terapéutica. Actas Urol. Esp. 1998, 22, 519–523. [Google Scholar]

- Dohm, A.; Sanchez, J.; Stotsky-Himelfarb, E.; Willingham, F.F.; Hoffe, S. Strategies to minimize late effects from pelvic radiotherapy. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2021, 41, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, T.A.; Green, J.T.; Beresford, M.; Wedlake, L.; Burden, S.; Davidson, S.E.; Lal, S.; Henson, C.C.; Andreyev, H.J.N. Interventions to reduce acute and late adverse gastrointestinal effects of pelvic radiotherapy for primary pelvic cancers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1, CD012529. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Helalah, M.; Mustafa, H.; Alshraideh, H.; Alsuhail, A.I.; Almousily, O.A.; Al-Abdallah, R.; Al Olayan, A. Quality of life and psychological wellbeing of colorectal cancer survivors in the KSA. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jitender, S.; Mahajan, R.; Rathore, V.; Choudhary, R. Quality of life of cancer patients. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 2018, 12, 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Fellia, T.; Sarafis, P.; Bouletis, A.; Tzenetidis, V.; Papathanasiou, I.; Apostolidi, T.P.; Gkena, N.; Nikolentzos, A.; Patsopoulou, A.; Malliarou, M. Correlation of cancer caregiver’s burden, stress, and their quality of life. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1425, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abrams, H.R.; Durbin, S.; Huang, C.X.; Johnson, S.F.; Nayak, R.K.; Zahner, G.J.; Peppercorn, J. Financial toxicity in cancer care: Origins, impact, and solutions. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 2043–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neibart, S.S.; Manne, S.L.; Jabbour, S.K. Quality of life after radiotherapy for rectal and anal cancer. Curr. Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2020, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, V.; Agarwal, A.; Popovic, M.; Cella, D.; McDonald, R.; Vuong, S.; Lam, H.; Rowbottom, L.; Chan, S.; Barakat, T.; et al. Comparison of the FACT-C, EORTC QLQ-CR38, and QLQ-CR29 quality of life questionnaires for patients with colorectal cancer: A literature review. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3661–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinsky, E.; Man, L.C.; MacKenzie, A.R. Health-related quality of life in older adults with colorectal cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whistance, R.N.; Conroy, T.; Chie, W.; Costantini, A.; Sezer, O.; Koller, M.; Johnson, C.D.; Pilkington, S.A.; Arraras, J.; Ben-Josef, E.; et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 questionnaire module to assess health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 3017–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baider, L.; Perez, T.; De-Nour, A. Gender and adjustment to chronic disease. A study of couples with colon cancer. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1989, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibble, S.; Padilla, G.; Dodd, M.; Miaskowski, C. Gender differences in the dimensions of quality of life. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 1998, 25, 577–583. [Google Scholar]

- Klemm, P.; Miller, M.; Fernsler, J. Demands of illness in people treated for colorectal cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2000, 27, 633–639. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, L.; Anderson, H. Stigma in patients with rectal cancer: A community study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1984, 38, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsberg, C.; Bjorvell, H.; Cedermark, B. Well-being and its relation to coping ability in patients with colorectal and gastric cancer before and after surgery. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 1996, 10, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsberg, C.; Cedermark, B. Well-being, general health and coping ability: 1-year follow-up of patients treated for colorectal and gastric cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 1996, 5, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, S.D.; Andersen, M.R.; Etzioni, R.; Moinpour, C.M.; Peacock, S.; Potosky, A.L.; Urban, N. Quality of life in survivors of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 1999, 88, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, R.M.; Holmes, A.; Klein, R.; Greene, J.; Dittus, R. Outcome states of colorectal cancer: Identification and description using patient focus groups. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1998, 93, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCosse, J.; Cennerazzo, W. Quality-of-life management of patients with colorectal cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 1997, 47, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, M.; van Knippenberg, F.; Van Dulmen, A.; Borne, H.V.D.; Henegouwen, G.V.B. Survival and psychosocial adjustment to stoma surgery and nonstoma bowel resection: A 4-year follow-up. J. Psychosom. Res. 1997, 42, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, M.J.; van Knippenberg, F.C.; van den Borne, H.W.; van Berge-Henegouwen, G.P. Psychosocial adaptation to stoma surgery: A review. J. Behav. Med. 1995, 18, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.; McMullen, C.K.; Altschuler, A.; Mohler, M.J.; Hornbrook, M.C.; Baldwin, C.M.; Herrinton, L.J.; Krouse, R.S. Gender differences in quality of life among long-term colorectal cancer survivors with ostomies. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2011, 38, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, T.B.; Gray, R.E.; Fitch, M. A qualitative study of patient perspectives on colorectal cancer. Cancer Pract. 2000, 8, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, J.; Loprinzi, C.L.; Kuross, S.; Miser, A.W.; O’FAllon, J.R.; Mahoney, M.R.; Heid, I.M.; Bretscher, M.; Vaught, N.L. Randomized comparison of four tools measuring overall quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 3662–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, A.; Porzsolt, F.; Osoba, D. Quality of life in oncology practice: Prognostic value of EORTC QLQ-C30 scores in patients with advanced malignancy. Eur. J. Cancer 1997, 33, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepson, C.; Schultz, D.; Lusk, E.; McCorkle, R. Enforced social dependency and its relationship to cancer survival. Cancer Pract. 1997, 5, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, A.B.; Venook, A.P.; Adam, M.; Chang, G.; Chen, Y.J.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cohen, S.A.; Cooper, H.S.; Deming, D.; Garrido-Laguna, I.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Rectal Cancer, Version 3. 2024. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2024, 22, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), Quality of Life Group, QLQ-C30 Questionnaire. Available online: https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaires/eortc-qlq-c30/ (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), Quality of Life Group, QLQ-CR29 Questionnaire. Available online: https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaires/qlq-cr29/ (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Altshuler, R.D.; Daschner, P.; Salvador Morales, C.; St Germain, D.C.; Guida, J.; Prasanna, P.G.S.; Buchsbaum, J.C. Older adults with cancer and common comorbidities—Challenges and opportunities in improving their cancer treatment outcomes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertelt-Prigione, S.; de Rooij, B.H.; Mols, F.; Oerlemans, S.; Husson, O.; Schoormans, D.; Haanen, J.B.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V. Sex-differences in symptoms and functioning in >5000 cancer survivors: Results from the PROFILES registry. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 156, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, S.; Leach, M.J.; White, V.M.; Webber, K.; Jefford, M.; Lisy, K.; Davis, N.; Millar, J.L.; Evans, S.; Emery, J.D.; et al. Health-related quality of life in rural cancer survivors compared with their urban counterparts: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2024, 32, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMarzio, P.; Peila, R.; Dowling, O.; Timony, D.M.; Balgobind, A.; Lee, L.N.; Kostroff, K.M.; Ho, G.Y.F. Smoking and alcohol drinking effect on radiotherapy-associated risk of second primary cancer and mortality among breast cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 57, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, L.; Ritmala-Castrén, M.; Nikander, P.; Mäkelä, S.; Vahlberg, T.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Empowering patient education on self-care activity among patients with colorectal cancer—A research protocol for a randomised trial. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manne, S.; Devine, K.; Hudson, S.; Kashy, D.; O’mAlley, D.; Paddock, L.E.; Bandera, E.V.; Llanos, A.A.M.; Fong, A.; Singh, N.; et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in a cohort of cancer survivors in New Jersey. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.K.; Nam, H.S.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.H. Health-related quality of life and associated comorbidities in community-dwelling women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Robinson, L.A.; Jensen, R.E.; Smith, T.G.; Yabroff, K.R. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among cancer survivors in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021, 5, pkaa123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, P.A.; Hays, R.D.; Spritzer, K.L.; Rogatko, A.; Ko, C.Y.; Colangelo, L.H.; Arora, A.; Hopkins, J.O.; Evans, T.L.; Yothers, G. Health-related quality of life outcomes after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer in NRG Oncology/NSABP R-04. Cancer 2022, 128, 3233–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaker, M.E.; Prins, M.C.; Schiphorst, A.H.; van Tuyl, S.A.; Pronk, A.; van den Bos, F. Long-term changes in physical capacity after colorectal cancer treatment. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2015, 6, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, B.; Akkaş, E.A.; Okur, Y.; Eren, A.A.; Eren, M.F.; Karapınar, H.; Babacan, N.A.; Kılıçkap, S. The impact of radiotherapy on quality of life for cancer patients: A longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 2014, 22, 2479–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rades, D.; Al-Salool, A.; Yu, N.Y.; Bartscht, T. Emotional distress prior to chemoradiation for rectal or anal cancer. In Vivo 2023, 37, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruheim, K.; Guren, M.G.; Skovlund, E.; Hjermstad, M.J.; Dahl, O.; Frykholm, G.; Carlsen, E.; Tveit, K.M. Late side effects and quality of life after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 76, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brændengen, M.; Tveit, K.M.; Bruheim, K.; Cvancarova, M.; Berglund, Å.; Glimelius, B. Late patient-reported toxicity after preoperative radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in nonresectable rectal cancer: Results from a randomized Phase III study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 81, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascoul-Mollevi, C.; Gourgou, S.; Borg, C.; Etienne, P.L.; Rio, E.; Rullier, E.; Juzyna, B.; Castan, F.; Conroy, T. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX and preoperative chemoradiotherapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (UNICANCER PRODIGE 23): Health-related quality of life longitudinal analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2023, 186, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benli Yavuz, B.; Aktan, M.; Kanyilmaz, G.; Demir, L.S. Assessment of quality of life following radiotherapy in patients with rectum cancer. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2022, 53, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marijnen, C.A.; Kapiteijn, E.; van de Velde, C.J.; Martijn, H.; Steup, W.H.; Wiggers, T.; Kranenbarg, E.K.; Leer, J.W. Acute side effects and complications after short-term preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision in primary rectal cancer: Report of a multicenter randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipaviciute, A.; Sileika, E.; Burneckis, A.; Dulskas, A. Late gastrointestinal toxicity after radiotherapy for rectal cancer: A systematic review. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2020, 35, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, D.G.; Gasalberti, D.P.; Goldstein, S. Radiation proctitis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wen-Pei, C.; Hsiu-Ju, J. Changes in fatigue in rectal cancer patients before and after therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2020, 28, 2513–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Janjan, N.A.; Guo, H.; Johnson, B.A.; Engstrom, M.C.; Crane, C.H.; Mendoza, T.R.; Cleeland, C.S. Fatigue during preoperative chemoradiation for resectable rectal cancer. Cancer 2001, 92 (Suppl. S6), 1725–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.M.; Grem, J.L.; Visovsky, C.; Marunda, H.A.; Yurkovich, J.M. Fatigue and other variables during adjuvant chemotherapy for colon and rectal cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2010, 37, E359–E369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mercado, V.J.; Lim, J.; Marrero, S.; Pedro, E.; Saligan, L.N. Gut microbiota and fatigue in rectal cancer patients: A cross-sectional pilot study. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4615–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Mercado, V.J.; Lim, J.; Yu, G.; Penedo, F.; Pedro, E.; Bernabe, R.; Tirado-Gómez, M.; Aouizerat, B. Co-occurrence of symptoms and gut microbiota composition before neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for rectal cancer: A proof of concept. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2021, 23, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatooni, M. Cancer pain: An evolutionary concept analysis. Prof. Case Manag. 2021, 26, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, C.; Denieffe, S.; Gooney, M. Literature review: Preoperative radiotherapy and rectal cancer – impact on acute symptom presentation and quality of life. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guren, M.G.; Dueland, S.; Skovlund, E.; Fosså, S.D.; Poulsen, J.P.; Tveit, K.M. Quality of life during radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2003, 39, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberman, D.; Mehus, B.; Elliott, S.P. Urinary adverse effects of pelvic radiotherapy. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2014, 3, 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Engels, B.; Tournel, K.; Everaert, H.; Hoorens, A.; Sermeus, A.; Christian, N.; Storme, G.; Verellen, D.; De Ridder, M. Phase II study of preoperative helical tomotherapy with a simultaneous integrated boost for rectal cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 83, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, J.; Holm, T.; Cedermark, B.; Altman, D.; Holmström, B.; Glimelius, B.; Mellgren, A. Late adverse effects of short-course preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2006, 93, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, Y.; Hirohata, A. Status and content of outpatient preoperative education for rectal cancer patients undergoing stoma surgery provided by Japanese wound, ostomy, and continence nurses: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livneh, H. Psychosocial adaptation to cancer: The role of coping strategies. J. Rehabil. 2000, 66, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Björkman, N.; Lambe, M.; Eaker, S.; Sandin, F.; Glimelius, B. Differences according to educational level in the management and survival of colorectal cancer in Sweden. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faury, S.; Koleck, M.; Foucaud, J.; M’Bailara, K.; Quintard, B. Patient education interventions for colorectal cancer patients with stoma: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, A.; Zhu, J.; Tang, H.; Zhu, X. Effect of self-efficacy intervention on quality of life of patients with intestinal stoma. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2018, 41, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmala, R.; Fokas, E.; Flentje, M.; Sauer, R.; Liersch, T.; Graeven, U.; Fietkau, R.; Hohenberger, W.; Arnold, D.; Hofheinz, R.D.; et al. Quality of Life in Rectal Cancer Patients with or without Oxaliplatin in the Randomised CAO/ARO/AIO-04 Phase 3 Trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 144, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristics | Number of Patients | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–49 | 6 | 9.4 |

| 50–69 | 41 | 64.1 | |

| ≥70 | 17 | 26.5 | |

| Sex | Male | 43 | 67.2 |

| Female | 21 | 32.8 | |

| Residence area | Urban | 36 | 56.3 |

| Rural | 28 | 43.7 | |

| Education level | Primary | 15 | 23.4 |

| Secondary | 39 | 60.9 | |

| Higher | 10 | 15.7 | |

| Smoker | No | 34 | 53.1 |

| yes | 30 | 46.9 | |

| Alcohol consumption | Rare/occasional | 23 | 35.9 |

| Moderate | 34 | 53.2 | |

| Chronic | 7 | 10.9 | |

| Clinicopathological Characteristics | Number of Patients | % | |

| Associated pathologies | Cardiovascular (CV) | 22 | 34.4 |

| CV + Diabetes | 7 | 10.9 | |

| Diabetes | 3 | 4.7 | |

| Other neoplasms for over 2 years | 3 | 4.7 | |

| Obesity | 3 | 4.7 | |

| Liver diseases | 2 | 3.1 | |

| No other pathologies | 24 | 37.5 | |

| Tumor location | Lower rectum | 20 | 31.2 |

| Middle rectum | 27 | 42.2 | |

| Upper rectum | 17 | 26.6 | |

| Tumor differentiation degree | G1 | 12 | 18.8 |

| G2 | 41 | 64.1 | |

| G3 | 11 | 17.2 | |

| Staging | IIIA | 24 | 37.5 |

| IIIB | 26 | 40.6 | |

| IIIC | 3 | 4.7 | |

| IV | 9 | 14.1 | |

| IIA | 2 | 3.1 | |

| CAPOX chemotherapy | Yes | 51 | 79.7 |

| No | 13 | 20.3 | |

| Functional Scale | Baseline Mean/CI 95% | After 15 RT Sessions Mean/CI 95% | After Completing RT Sessions Mean/CI 95% | p-Value | ANOVA Statistic | Eta Squared (η2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 8.31/ [7.83, 8.8] | 8.88/ [8.2, 9.55] | 10.16/ [9.37, 10.95] | 0.00054 | 7.83 | 0.0765 |

| Social role fulfillment | 3.86/ [3.4, 4.32] | 4.02/ [3.58, 4.45] | 4.7/ [4.27, 5.14] | 0.021256 | 3.93 | 0.0399 |

| Emotional functioning | 7.78/ [7.14, 8.42] | 8.17/ [7.47, 8.87] | 9.55/ [8.81, 10.29] | 0.001304 | 6.88 | 0.0679 |

| Social functioning | 3.3/ [2.95, 3.64] | 3.67/ [3.28, 4.06] | 4.3/ [3.88, 4.71] | 0.001588 | 6.67 | 0.0659 |

| Total functioning scale | 23.25/ [21.91, 24.59] | 24.73/ [23.02, 26.45] | 28.7/ [26.67, 30.74] | 0.000055 | 10.34 | 0.0986 |

| Functional Scale | Baseline Mean/CI 95% | After 15 RT Sessions Mean/CI 95% | After Completing RT Sessions Mean/CI 95% | p-Value | ANOVA Statistic | Eta Squared (η2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 5.91/ [5.41, 6.41] | 6.19/ [5.65, 6.72] | 7.48/ [6.85, 8.12] | 0.00023 | 8.75 | 0.0848 |

| Pain | 4.69/ [4.22, 5.16] | 5.98/ [5.46, 6.51] | 7.3/ [6.78, 7.82] | <0.0001 | 25.67 | 0.2136 |

| Loss of appetite and taste alteration | 5.22/ [4.74, 5.7] | 5.12/ [4.72, 5.53] | 5.83/ [5.32, 6.33] | 0.07606 | 2.61 | 0.0269 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 2.98/ [2.64, 3.33] | 2.92/ [2.62, 3.22] | 3.34/ [3.0, 3.69] | 0.16272 | 1.83 | 0.019 |

| Urinary symptoms | 6.89/ [6.36, 7.42] | 7.89/ [7.36, 8.42] | 9.42/ [8.24, 10.61] | 0.00012 | 9.48 | 0.0912 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 10.2/ [9.43, 10.97] | 10.77/ [10.09, 11.44] | 12.98/ [12.12, 13.85] | <0.0001 | 13.92 | 0.1284 |

| Hair loss | 1.17/ [1.04, 1.3] | 1.22/ [1.08, 1.35] | 1.25/ [1.08, 1.42] | 0.7537 | 0.28 | 0.003 |

| Total symptom scale | 37.06/ [34.58, 39.55] | 40.09/ [37.91, 42.28] | 47.61/ [44.28, 50.94] | <0.0001 | 15.42 | 0.1403 |

| Patient Variable | χ2 Value | Degrees of Freedom (df) | χ2 Threshold | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy (yes/no) | 0.4 | 1 | 3.84 | 0.5261 |

| Disease stage | 14.19 | 4 | 9.49 | 0.0067 |

| Degree of differentiation | 4.13 | 2 | 5.99 | 0.127 |

| Tumor localization | 1.2 | 2 | 5.99 | 0.549 |

| Associated pathologies | 6.43 | 6 | 12.59 | 0.3768 |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.56 | 2 | 5.99 | 0.7547 |

| Smoking | 0 | 1 | 3.84 | 1 |

| Education | 9.7 | 2 | 5.99 | 0.0078 |

| Residence area | 0.32 | 1 | 3.84 | 0.5721 |

| Sex | 8.66 | 1 | 3.84 | 0.0032 |

| Age | 64.42 | 2 | 5.99 | 0.0004 |

| Scale | Baseline Mean/CI 95% | After 15 RT Sessions Mean/CI 95% | After Completing RT Sessions Mean/CI 95% | p-Value | ANOVA Statistic | Eta Squared (η2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients without stoma | GI symptoms | 7.14/ [6.55, 7.72] | 7.96/ [7.25, 8.68] | 9.35/ [8.52, 10.19] | 0.000151 | 9.34 | 0.1107 |

| Emotional functioning | 1.94/ [1.68, 2.2] | 2.12/ [1.87, 2.36] | 2.39/ [2.12, 2.66] | 0.05345 | 2.99 | 0.0383 | |

| Pain | 1.43/ [1.25, 1.62] | 2.22/ [1.97, 2.46] | 2.75/ [2.53, 2.96] | <0.0001 | 36.01 | 0.3244 | |

| Global QoL | 10.24/ [9.49, 10.98] | 9.41/ [8.59, 10.23] | 9.16/ [8.5, 9.81] | 0.112498 | 2.22 | 0.0287 | |

| Patients with stoma | GI symptoms | 6.23/ [5.34, 7.12] | 7.92/ [6.43, 9.42] | 10.38/ [8.99, 11.78] | 0.000331 | 10.09 | 0.3593 |

| Emotional functioning | 2.38/ [1.91, 2.86] | 2.23/ [1.68, 2.78] | 3.15/ [2.72, 3.59] | 0.028437 | 3.94 | 0.1795 | |

| Pain | 1.62/ [1.26, 1.97] | 2.23/ [1.68, 2.78] | 2.31/ [1.79, 2.82] | 0.1057 | 2.39 | 0.1174 | |

| Stoma care difficulties | 2.0/ [1.5, 2.5] | 2.31/ [1.7, 2.91] | 2.38/ [1.97, 2.8] | 0.549564 | 0.61 | 0.0327 | |

| Global QoL | 10.31/ [8.6, 12.02] | 10.31/ [8.81, 11.8] | 9.46/ [7.96, 10.96] | 0.69241 | 0.37 | 0.0202 | |

| Assessment Time Point | Functioning Scale | Mean Score (SD) | t-Statistic | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with Chemotherapy | Patients Without Chemotherapy | ||||

| Baseline | Physical functioning | 8.14 (1.81) | 9.00 (2.48) | −1.18 | 0.26 |

| Social role fulfillment | 3.86 (1.92) | 3.85 (1.77) | 0.03 | 0.98 | |

| Emotional functioning | 7.90 (2.74) | 7.31 (1.93) | 0.9 | 0.38 | |

| Social functioning | 3.33 (1.48) | 3.15 (1.07) | 0.5 | 0.62 | |

| Total functioning scale | 23.24 (5.52) | 23.31 (5.51) | −0.04 | 0.97 | |

| After 15 RT sessions | Physical functioning | 8.98 (2.89) | 8.46 (2.22) | 0.7 | 0.49 |

| Social role fulfillment | 4.04 (1.84) | 3.92 (1.55) | 0.23 | 0.82 | |

| Emotional functioning | 8.29 (3.05) | 7.69 (1.97) | 0.87 | 0.39 | |

| Social functioning | 3.69 (1.68) | 3.62 (1.26) | 0.17 | 0.87 | |

| Total functioning scale | 25.00 (7.24) | 23.69 (6.05) | 0.67 | 0.51 | |

| After completing RT sessions | Physical functioning | 10.04 (3.25) | 10.62 (3.20) | −0.58 | 0.57 |

| Social role fulfillment | 4.69 (1.85) | 4.77 (1.54) | −0.17 | 0.87 | |

| Emotional functioning | 9.47 (3.12) | 9.85 (2.64) | −0.44 | 0.66 | |

| Social functioning | 4.25 (1.72) | 4.46 (1.61) | −0.41 | 0.69 | |

| Total functioning scale | 28.45 (8.48) | 29.69 (7.75) | −0.51 | 0.62 | |

| Assessment Time Point | Symptom Scale | Mean score (SD) | t-Statistic | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with Chemotherapy | Patients Without Chemotherapy | ||||

| Baseline | Fatigue | 5.29 (2.19) | 5.62 (1.84) | −0.58 | 0.57 |

| Pain | 8.56 (1.39) | 9.15 (1.13) | −0.62 | 0.54 | |

| Loss of appetite and taste alteration | 5.74 (1.88) | 5.31 (1.66) | 0.57 | 0.57 | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 2.76 (1.02) | 2.92 (0.48) | −0.26 | 0.79 | |

| Urinary symptoms | 7.85 (1.47) | 7.38 (1.14) | 0.63 | 0.53 | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 13.32 (2.91) | 13.85 (2.73) | −0.53 | 0.6 | |

| Hair loss | 2.62 (1.00) | 2.46 (0.69) | 0.32 | 0.75 | |

| Total symptom scale | 46.15 (5.76) | 46.69 (4.98) | −0.24 | 0.81 | |

| After 15 RT sessions | Fatigue | 5.10 (2.08) | 5.38 (1.76) | −0.39 | 0.7 |

| Pain | 8.74 (1.41) | 8.77 (1.32) | −0.04 | 0.97 | |

| Loss of appetite and taste alteration | 6.02 (1.60) | 5.54 (1.39) | 0.56 | 0.58 | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 2.98 (0.99) | 3.15 (0.76) | −0.25 | 0.81 | |

| Urinary symptoms | 7.66 (1.58) | 7.62 (1.66) | 0.04 | 0.97 | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 13.54 (2.92) | 13.92 (2.67) | −0.3 | 0.76 | |

| Hair loss | 2.50 (0.94) | 2.31 (0.76) | 0.33 | 0.74 | |

| Total symptom scale | 46.54 (4.77) | 46.69 (5.07) | −0.07 | 0.94 | |

| After completing RT sessions | Fatigue | 5.42 (2.27) | 5.54 (2.50) | −0.15 | 0.88 |

| Pain | 8.88 (1.56) | 8.69 (1.80) | 0.16 | 0.87 | |

| Loss of appetite and taste alteration | 6.12 (2.01) | 5.92 (2.26) | 0.2 | 0.85 | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 3.08 (4.53) | 2.92 (1.59) | 0.22 | 0.83 | |

| Urinary symptoms | 7.88 (1.61) | 7.46 (2.13) | 0.46 | 0.65 | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 13.77 (2.32) | 13.54 (2.63) | 0.17 | 0.87 | |

| Hair loss | 2.69 (1.00) | 2.38 (0.96) | 0.51 | 0.61 | |

| Total symptom scale | 47.85 (8.84) | 46.92 (8.83) | 0.29 | 0.77 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schenker, M.; Bițînă, L.C.; Schenker, R.A.; Ciurea, A.-M.; Mehedințeanu, A.M.; Berisha, T.C.; Bratu, L.D.; Cara, M.L.; Dicianu, A.M.; Stovicek, P.O. Prospective Evaluation of the Influence of Chemoradiotherapy and Stoma on Functional and Symptomatic Outcomes in Rectal Cancer Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17122052

Schenker M, Bițînă LC, Schenker RA, Ciurea A-M, Mehedințeanu AM, Berisha TC, Bratu LD, Cara ML, Dicianu AM, Stovicek PO. Prospective Evaluation of the Influence of Chemoradiotherapy and Stoma on Functional and Symptomatic Outcomes in Rectal Cancer Patients. Cancers. 2025; 17(12):2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17122052

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchenker, Michael, Luiza Cristiana Bițînă, Ramona Adriana Schenker, Ana-Maria Ciurea, Alina Maria Mehedințeanu, Tradian Ciprian Berisha, Lucian Dragoș Bratu, Monica Laura Cara, Andrei Mircea Dicianu, and Puiu Olivian Stovicek. 2025. "Prospective Evaluation of the Influence of Chemoradiotherapy and Stoma on Functional and Symptomatic Outcomes in Rectal Cancer Patients" Cancers 17, no. 12: 2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17122052

APA StyleSchenker, M., Bițînă, L. C., Schenker, R. A., Ciurea, A.-M., Mehedințeanu, A. M., Berisha, T. C., Bratu, L. D., Cara, M. L., Dicianu, A. M., & Stovicek, P. O. (2025). Prospective Evaluation of the Influence of Chemoradiotherapy and Stoma on Functional and Symptomatic Outcomes in Rectal Cancer Patients. Cancers, 17(12), 2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17122052