The Role of Social Support in Buffering the Financial Toxicity of Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study of Patient Experiences

Simple Summary

Abstract

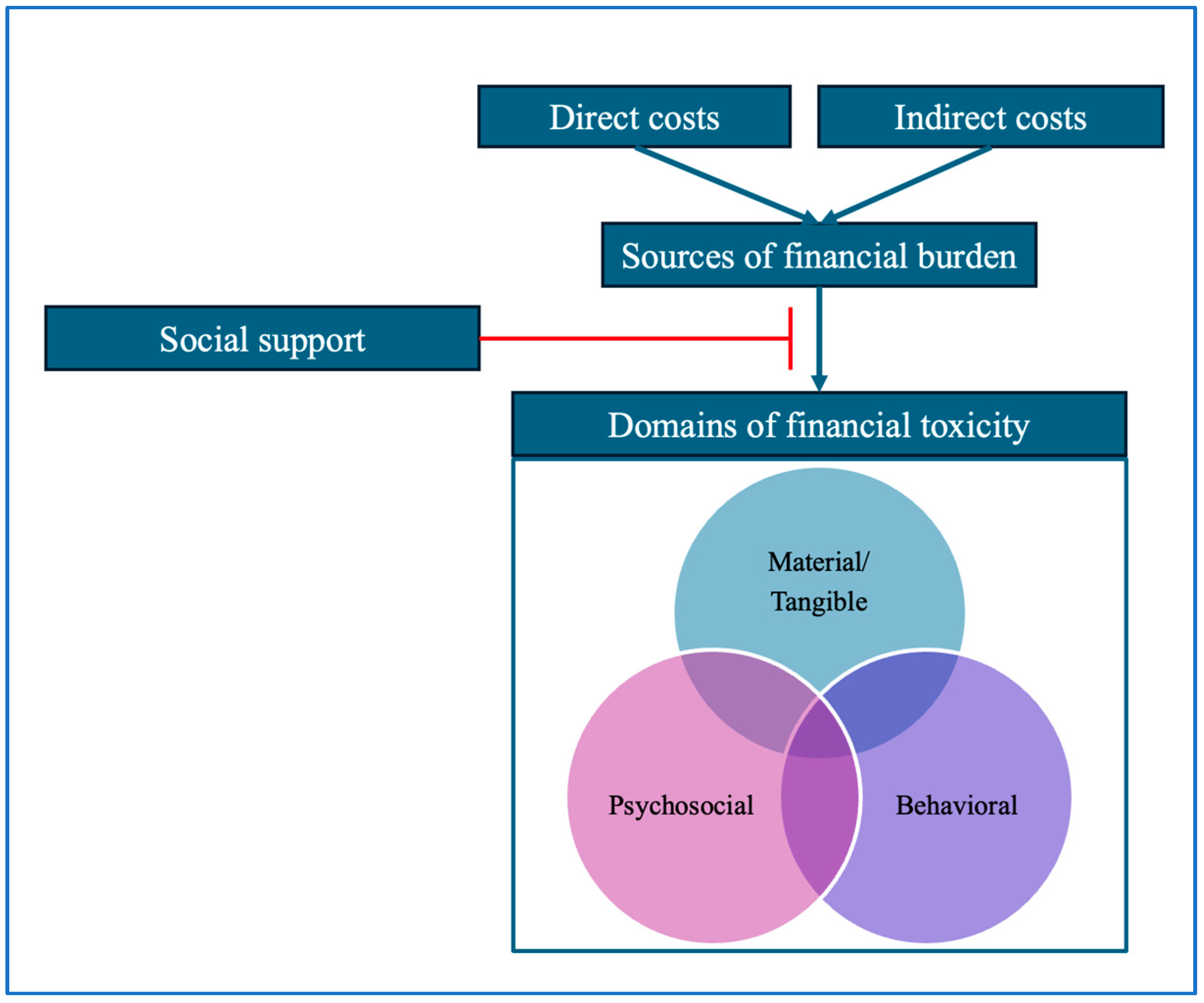

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Support in the Material/Tangible Domain

[Friends] set up a GoFundMe because I had an issue with my insurance and they… did a GoFundMe to like help cover any time off work and any procedures I needed and stuff like that.

I was able to get [to appointments] in a decent amount of time, but it did take a toll with gas. However, I had some really good people, some really supportive people in my life and my staff … took up a collection and gave me a huge gift card. That was just unbelievable. And I was able to use that for a lot of my gas expense.

The Pink Ribbon Girls, they really stepped up and they took me to most all of my appointments. They even took me to one of my surgeries, you know, at like five something in the morning.

| Support System | Participant Quotes |

|---|---|

| Family | “I never worried … because my dad’s helping me out. But I knew my bills were going to be paid and my dad, he filled in those gaps between the disability and my job. And then if I needed something in between. And I will say my son’s father did step up to the plate, too.” |

| “My other sister, she would come and get me and take me to the pharmacy to pick up my prescriptions and stuff like that.” | |

| Friends | “They [friends] collected money for me, they collected over $670. That paid my rent, my internet bill, put food in my house, and left me with money.” |

| “Like, one of my friends paid my cell phone bill for a couple months, which was amazing. And like I said, without their help, it would have been a lot harder. And I felt really bad that they did that because I’m pretty proud, you know. But it was amazing and let me know how much they care that they did do it.” | |

| Community | “I do recall maybe last year or the year before, they did a program at [the cancer center] and they did assist me with my medicine. … They helped me out paying for my medicine. So that helped me out so much.” |

| “I was fortunate in that [I am] someone who knows a lot of people and who’s known a lot of people in the community. I mean, I had GoFundMes and stuff like that. I would have lost my house, would have been homeless, without a doubt, without community support.” |

3.2. Social Support in the Psychosocial Domain

…being able to have those meals available or gift cards to help out. I mean, just those little day-to-days that we take for granted, they become a bigger deal when you’re struggling with that diagnosis and trying to get through surgeries.

I was living off the grace of God, by God sending me people in my life, just different strangers. They helped me get by. And then my job started to, my co-workers were like doing a fundraiser for me, so they would go around and do fundraisers. Like, hey, we try to raise money for [participant’s name]…

It was surprising how I would get just cards in the mail occasionally, just out of the blue, and that was something that was just so sweet. Sometimes, you know, we get like a gift card for gas or, you know, a restaurant. One time we got one for, you know, Dairy Queen. Just, you know, it just said, go get some ice cream and have fun … That and often it was from people… I never would have thought would send something to us.

| Support System | Participant Quotes |

|---|---|

| Family | “She’d [mother] come over and make sure that I had something to eat. And you know, just basically checking in on me, and just making sure that I’m okay.” |

| Friends | “[Friends] took care of [my son] for me and they wouldn’t let me pay them either. I had a great support system, I don’t know what I would have done without them though, I don’t know how I would have made it through.” |

| Community | “We live in a pretty amazing community where I had a lot of food and a lot of gift cards given to us. So, that burden was lifted for a period of time and in a really, really beautiful way.” |

3.3. Effects of Social Support on the Behavioral Domain

His [husband’s] sister was a big, big help, like with the kids. And she loaned us $10 or $20 here and there, just to get us through. My mom and dad would loan us $20, $30 to get us through. We had a little bit of support here and there. But there was times where I just couldn’t make my appointment because I didn’t have the gas to go; I’d have to change my appointment day.

My son lives [near the cancer center]…, and I’m able to work remote for my job. So, I had a lot of luxuries that I know a lot of people don’t have—where I stayed with him the whole week, and I worked from his place, and I went and had my treatments and went back to his place. So, I was, I was pretty fortunate where I didn’t have to worry about paying for room and board, and gas, and all that. Probably not everyone has that, unfortunately.

| Support System | Participant Quotes |

|---|---|

| Family | “I planned my chemo days around [my husband] because he works, he gets two days off…. He is set in stone like he knows exactly where he’s going every day. He goes to the same stops at the same time every day, like he has his routine. And I didn’t want him to up end any of that, you know, because I was thinking of his needs. He was like, ‘I’m thinking of your needs.’ I’m thinking of his needs…I went to the [the cancer center’s] schedule arm. Like, ‘I don’t care what time, what day as long as it’s on a Thursday. Can we make all of my chemo on a Thursday?’ And the scheduler said, ‘Yeah, I think we can do that.’” |

| Friends | “Just friends who came to visit, wrote cards, sent care packages, that kind of thing… My friend from Germany came and my friend from Korea and I don’t think that they could pick Ohio on a map. And so just like having people care enough to be there with you and be in the thick of it was just so comforting. And it just helped me get kind of through everything, because looking uphill at … 16 chemo treatments, just everything. You kind of are, like, am I ever gonna get through that?” |

| Community | “And there was an [academic medical center] thing for Christmas gifts for my daughter, I forget what it’s called. I think it’s through this, [the cancer center] is how I found out about it. Like, they were like, oh, you should apply for this and while you’re going through like active surgery or treatment, they provide like Christmas gifts for your family…That was a really great program.” |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

| RUCC | Rural–Urban Continuum Codes |

| YA | Young adults |

References

- Coughlin, S.S.; Ayyala, D.N.; Tingen, M.S.; Cortes, J.E. Financial Distress among Breast Cancer Survivors. Curr. Cancer Rep. 2020, 2, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, M.; Pan, J.; Rai, S.N.; Eldredge-Hindy, H. Financial Toxicity in Women with Breast Cancer Receiving Radiation Therapy: Final Results of a Prospective Observational Study. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 12, e79–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebli, P.; Lemus, J.; Avila, C.; Peña, K.; Mariscal, B.; Merlos, S.; Guitelman, J.; Molina, Y. Multilevel Determinants of Financial Toxicity in Breast Cancer Care: Perspectives of Healthcare Professionals and Latina Survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3179–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, B.; Kimmick, G.; Altomare, I.; Marcom, P.K.; Houck, K.; Zafar, S.Y.; Peppercorn, J. Patient Experience and Attitudes toward Addressing the Cost of Breast Cancer Care. Oncologist 2014, 19, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, M.; West, M.; Matthews, J.; Stokan, M.; Kook, Y.; Gallups, S.; Diergaarde, B. Financial Toxicity among Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2019, 46, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Olvera, R.G.; Shiu-Yee, K.; Rush, L.J.; Tarver, W.L.; Blevins, T.; McAlearney, A.S.; Andersen, B.L.; Paskett, E.D.; Carson, W.E.; et al. Short-Term and Long-Term Financial Toxicity from Breast Cancer Treatment: A Qualitative Study. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 32, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offodile, A.C.; Asaad, M.; Boukovalas, S.; Bailey, C.; Lin, Y.-L.; Teshome, M.; Greenup, R.A.; Butler, C. Financial Toxicity Following Surgical Treatment for Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 2451–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, S.Y.; Abernethy, A.P. Financial Toxicity, Part I: A New Name for a Growing Problem. Oncology 2013, 27, 80–149. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, J.; Mehlis, K.; Surmann, B.; Lingnau, R.; Damm, O.; Greiner, W.; Winkler, E.C. Methods for Measuring Financial Toxicity after Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment: A Systematic Review and Its Implications. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altice, C.K.; Banegas, M.P.; Tucker-Seeley, R.D.; Yabroff, K.R. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djw205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.B.; Spencer, J.C.; Pinheiro, L.C.; Carey, L.A.; Olshan, A.F.; Reeder-Hayes, K.E. Financial Impact of Breast Cancer in Black versus White Women. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1695–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, S.P.; Aviki, E.; Sevilimedu, V.; Thom, B.; Gemignani, M.L. Financial Toxicity Among Women with Breast Cancer Varies by Age and Race. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 8040–8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politi, M.C.; Yen, R.W.; Elwyn, G.; O’Malley, A.J.; Saunders, C.H.; Schubbe, D.; Forcino, R.; Durand, M.-A. Women Who Are Young, Non-White, and with Lower Socioeconomic Status Report Higher Financial Toxicity up to 1 Year after Breast Cancer Surgery: A Mixed-Effects Regression Analysis. Oncologist 2021, 26, e142–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meernik, C.; Sandler, D.P.; Peipins, L.A.; Hodgson, M.E.; Blinder, V.S.; Wheeler, S.B.; Nichols, H.B. Breast Cancer-Related Employment Disruption and Financial Hardship in the Sister Study. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021, 5, pkab024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Gyasi, S.; Timsina, L.R.; Bhattacharyya, O.; Fisher, C.S.; Haggstrom, D.A. Bankruptcy among Insured Surgical Patients with Breast Cancer: Who Is at Risk? Cancer 2021, 127, 2083–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzone, J.; Welch, C.; Morgans, A.; Bhanvadia, S.K.; Mossanen, M.; Shenhav-Goldberg, R.; Chandrasekar, T.; Pinkhasov, R.; Shapiro, O.; Jacob, J.M.; et al. Association of Race with Cancer-Related Financial Toxicity. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 18, e271–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M.; Henrikson, N.B.; Panattoni, L.; Syrjala, K.L.; Shankaran, V. A Theoretical Model of Financial Burden After Cancer Diagnosis. Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 3095–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Survivor Views. Available online: https://www.fightcancer.org/survivor-views (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Jones, S.M.; Yi, J.; Henrikson, N.B.; Panattoni, L.; Shankaran, V. Financial Hardship after Cancer: Revision of a Conceptual Model and Development of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Future Sci. OA 2024, 10, FSO983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraav, S.-L.; Lehto, S.M.; Kauhanen, J.; Hantunen, S.; Tolmunen, T. Loneliness and Social Isolation Increase Cancer Incidence in a Cohort of Finnish Middle-Aged Men. A Longitudinal Study. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 299, 113868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, C.; Ostir, G.V.; Du, X.; Peek, M.K.; Goodwin, J.S. The Influence of Marital Status on the Stage at Diagnosis, Treatment, and Survival of Older Women with Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2005, 93, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.S.; Armstrong, G.E.; Gaumond, J.S.; Vigoureux, T.F.D.; Miller, C.H.; Sanford, S.D.; Salsman, J.M.; Katsanis, E.; Badger, T.A.; Reed, D.R.; et al. Social Isolation and Social Connectedness among Young Adult Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Cancer 2023, 129, 2946–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, A. Impact of Social Isolation, Physician-Patient Communication, and Self-Perception on the Mental Health of Patients With Cancer and Cancer Survivors: National Survey Analysis. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2023, 12, e45382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, M.; Brähler, E.; Wild, P.; Faber, J.; Merzenich, H.; Ernst, M. Loneliness as a Risk Factor for Suicidal Ideation and Anxiety in Cancer Survivor Populations. J. Psychosom. Res. 2022, 157, 110827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, N.L.; Mady, L.J.; Armache, M.; Hearn, M.; Stemme, R.; Jagsi, R.; Gharzai, L.A. Screening for Financial Toxicity Among Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. JACR 2024, 21, 1380–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA ERS—Rural-Urban Continuum Codes 2013. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis: Implications for Conducting a Qualitative Descriptive Study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armat, M.R.; Assarroudi, A.; Rad, M.; Sharifi, H.; Heydari, A. Inductive and Deductive: Ambiguous Labels in Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Rep. 2018, 23, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åslund, C.; Larm, P.; Starrin, B.; Nilsson, K.W. The Buffering Effect of Tangible Social Support on Financial Stress: Influence on Psychological Well-Being and Psychosomatic Symptoms in a Large Sample of the Adult General Population. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.B.; Manning, M.L.; Gellin, M.; Padilla, N.; Spees, L.P.; Biddell, C.B.; Petermann, V.; Deal, A.; Rogers, C.; Rodriguez-O’Donnell, J.; et al. Impact of a Comprehensive Financial Navigation Intervention to Reduce Cancer-Related Financial Toxicity. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 2024, 22, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, M. Studying Guaranteed Income in Oncology: Lessons Learned From Launching the Guaranteed Income and Financial Treatment Trial. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. JACR 2024, 21, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moor, J.S.; Mollica, M.; Sampson, A.; Adjei, B.; Weaver, S.J.; Geiger, A.M.; Kramer, B.S.; Grenen, E.; Miscally, M.; Ciolino, H.P. Delivery of Financial Navigation Services Within National Cancer Institute–Designated Cancer Centers. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021, 5, pkab033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levit, L.A.; Byatt, L.; Lyss, A.P.; Paskett, E.D.; Levit, K.; Kirkwood, K.; Schenkel, C.; Schilsky, R.L. Closing the Rural Cancer Care Gap: Three Institutional Approaches. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppercorn, J.; Gelin, M.; Masteralexis, T.E.; Zafar, S.Y.; Nipp, R.D. Screening for Financial Toxicity in Oncology Research and Practice: A Narrative Review. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2025, 21, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leraas, H.; Moya-Mendez, M.; Donohue, V.; Kawano, B.; Olson, L.; Sekar, A.; Robles, J.; Wagner, L.; Greenup, R.; Haines, K.L.; et al. Using Crowdfunding Campaigns to Examine Financial Toxicity and Logistical Burdens Facing Families of Children With Wilms Tumor. J. Surg. Res. 2023, 291, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.M.; Huang, D.S.; Rimel, B.J.; Kim, K.H.; Li, A.J.; Taylor, K.N.; Liang, M.I. Unmet Financial Needs among Patients Crowdfunding to Support Gynecologic Cancer Care. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 186, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, K.R.; Black, K.Z.; Baker, S.; Cothern, C.; Davis, K.; Doost, K.; Goestch, C.; Griesemer, I.; Guerrab, F.; Lightfoot, A.F.; et al. Racial Differences in the Influence of Health Care System Factors on Informal Support for Cancer Care Among Black and White Breast and Lung Cancer Survivors. Fam. Community Health 2020, 43, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.; Pérez, M.; Kreuter, M.; Margenthaler, J.; Colditz, G.; Jeffe, D.B. Perceived Social Support in African American Breast Cancer Patients: Predictors and Effects. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 192, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Lane, J.M.; Xu, X.; Sörensen, S. Investigating Racial Disparities in Cancer Crowdfunding: A Comprehensive Study of Medical GoFundMe Campaigns. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e51089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, J.A.; Yap, B.J.; Wroblewski, K.; Blinder, V.; Araújo, F.S.; Hlubocky, F.J.; Nicholas, L.H.; O’Connor, J.M.; Brockstein, B.; Ratain, M.J.; et al. Measuring Financial Toxicity as a Clinically Relevant Patient-Reported Outcome: The Validation of the COmprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 2017, 123, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultz, B.D.; Cummings, G.G.; Grassi, L.; Travado, L.; Hoekstra-Weebers, J.; Watson, M. 2013 President’s Plenary International Psycho-Oncology Society: Embracing the IPOS Standards as a Means of Enhancing Comprehensive Cancer Care. Psychooncology. 2014, 23, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottaro, R.; Craparo, G.; Faraci, P. What Is the Direction of the Association between Social Support and Coping in Cancer Patients? A Systematic Review. J. Health Psychol. 2023, 28, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dev, R.; Agosta, M.; Fellman, B.; Reddy, A.; Baldwin, S.; Arthur, J.; Haider, A.; Carmack, C.; Hui, D.; Bruera, E. Coping Strategies and Associated Symptom Burden Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. Oncologist 2024, 29, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nipp, R.D.; Zullig, L.L.; Samsa, G.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Schrag, D.; Taylor, D.H., Jr.; Abernethy, A.P.; Zafar, S.Y. Identifying Cancer Patients Who Alter Care or Lifestyle Due to Treatment-Related Financial Distress. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, M.; Gardner, D.; Finik, J. The Financial Coping Strategies of US Cancer Patients and Survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5753–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olvera, R.G.; Myers, S.P.; Gaughan, A.A.; Tarver, W.L.; Lee, S.; Shiu, K.; Rush, L.J.; Blevins, T.; Obeng-Gyasi, S.; McAlearney, A.S. The Role of Social Support in Buffering the Financial Toxicity of Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study of Patient Experiences. Cancers 2025, 17, 1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101712

Olvera RG, Myers SP, Gaughan AA, Tarver WL, Lee S, Shiu K, Rush LJ, Blevins T, Obeng-Gyasi S, McAlearney AS. The Role of Social Support in Buffering the Financial Toxicity of Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study of Patient Experiences. Cancers. 2025; 17(10):1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101712

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlvera, Ramona G., Sara P. Myers, Alice A. Gaughan, Willi L. Tarver, Sandy Lee, Karen Shiu, Laura J. Rush, Tessa Blevins, Samilia Obeng-Gyasi, and Ann Scheck McAlearney. 2025. "The Role of Social Support in Buffering the Financial Toxicity of Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study of Patient Experiences" Cancers 17, no. 10: 1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101712

APA StyleOlvera, R. G., Myers, S. P., Gaughan, A. A., Tarver, W. L., Lee, S., Shiu, K., Rush, L. J., Blevins, T., Obeng-Gyasi, S., & McAlearney, A. S. (2025). The Role of Social Support in Buffering the Financial Toxicity of Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study of Patient Experiences. Cancers, 17(10), 1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101712