Left Behind: The Unmet Need for Breast Cancer Research in Mississippi

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

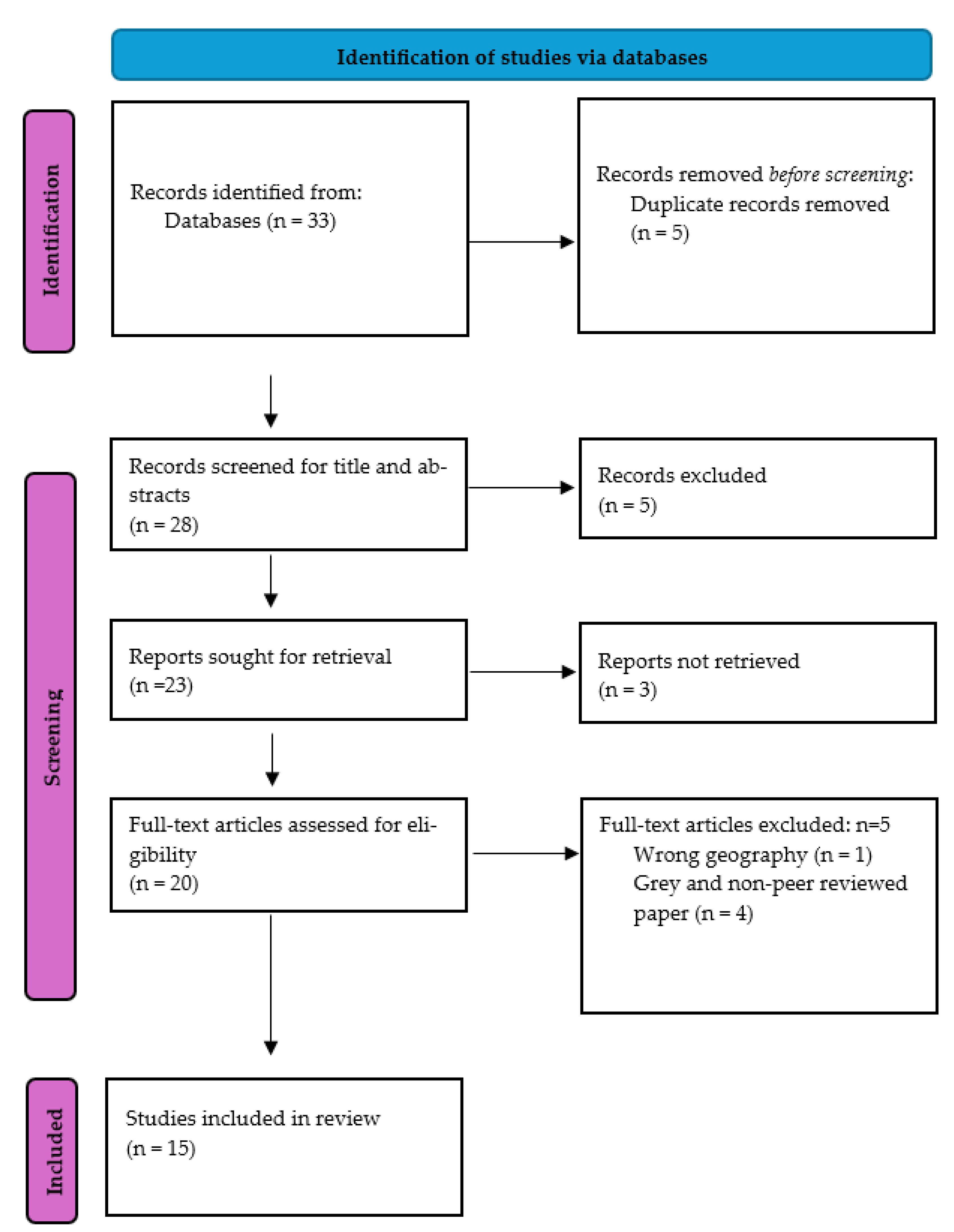

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Epidemiology of Breast Cancer in Mississippi

3.3. Cancer Screening, Access to Care, and Programs

3.4. Study Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. Racial Disparities

4.2. Screening and Treatment Access

4.3. Registry Trends and Regional Comparisons

4.4. Research Imbalance Across Southern States

4.5. Socioeconomic and Healthcare Infrastructure Challenges

4.6. Environmental and Genetic Contributors

4.7. Advancing Research and Bridging Gaps

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breast Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breast-cancer/statistics/index.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Newman, L.A.; Freedman, R.A.; Smith, R.A.; Star, J.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yedjou, C.G.; Sims, J.N.; Miele, L.; Noubissi, F.; Lowe, L.; Fonseca, D.D.; Alo, R.A.; Payton, M.; Tchounwou, P.B. Health and Racial Disparity in Breast Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1152, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Explore Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/#!/cancer-site/Breast (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Mississippi Cancer Registry. Age-Adjusted Cancer Incidence Rates by County in Mississippi, Female Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer-rates.info/ms/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Mississippi State Department of Health. Preventing Breast Cancer. Available online: https://msdh.ms.gov/page/41,14345,103.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- The EndNote Team EndNote. EndNote 21; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Higginbotham, J.C.; Moulder, J.; Currier, M. Rural v. urban aspects of cancer: First-year data from the Mississippi Central Cancer Registry. Fam. Community Health 2001, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.K.; Faruque, F.S. Breast cancer incidence and exposure to environmental chemicals in 82 counties in Mississippi. South. Med. J. 2004, 97, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSantis, C.; Jemal, A.; Ward, E.; Thun, M.J. Temporal trends in breast cancer mortality by state and race. Cancer Causes Control. 2008, 19, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, G.A. Breast cancer in Mississippi: What can we do? J. Miss. State Med. Assoc. 2009, 50, 299–301. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Anderson, K.; Williams, P.R.; Beacham, T.; McDonald, N. Breast health teaching in predominantly African American rural Mississippi Delta. ABNF J. 2013, 24, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Keeton, K.M.; Jones, E.S.; Sebastian, S. Breast cancer in Mississippi: Impact of race and residential geographical setting on cancer at initial diagnosis. South. Med. J. 2014, 107, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.N.; Bradley, D.L.; Zhang, X.; Faruque, F.; Duhe, R.J. The geographic distribution of mammography resources in Mississippi. Online J. Public. Health Inform. 2014, 5, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune, M.L. The impact of the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program on breast cancer outcomes for women in Mississippi. J. Cancer Policy 2015, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield-Johnson, S.; Fastring, D.; Fortune, M.; White-Johnson, F. Addressing Breast Cancer Health Disparities in the Mississippi Delta Through an Innovative Partnership for Education, Detection, and Screening. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortune, M.L. The Influence of Social Determinants on Late Stage Breast Cancer for Women in Mississippi. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, 4, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

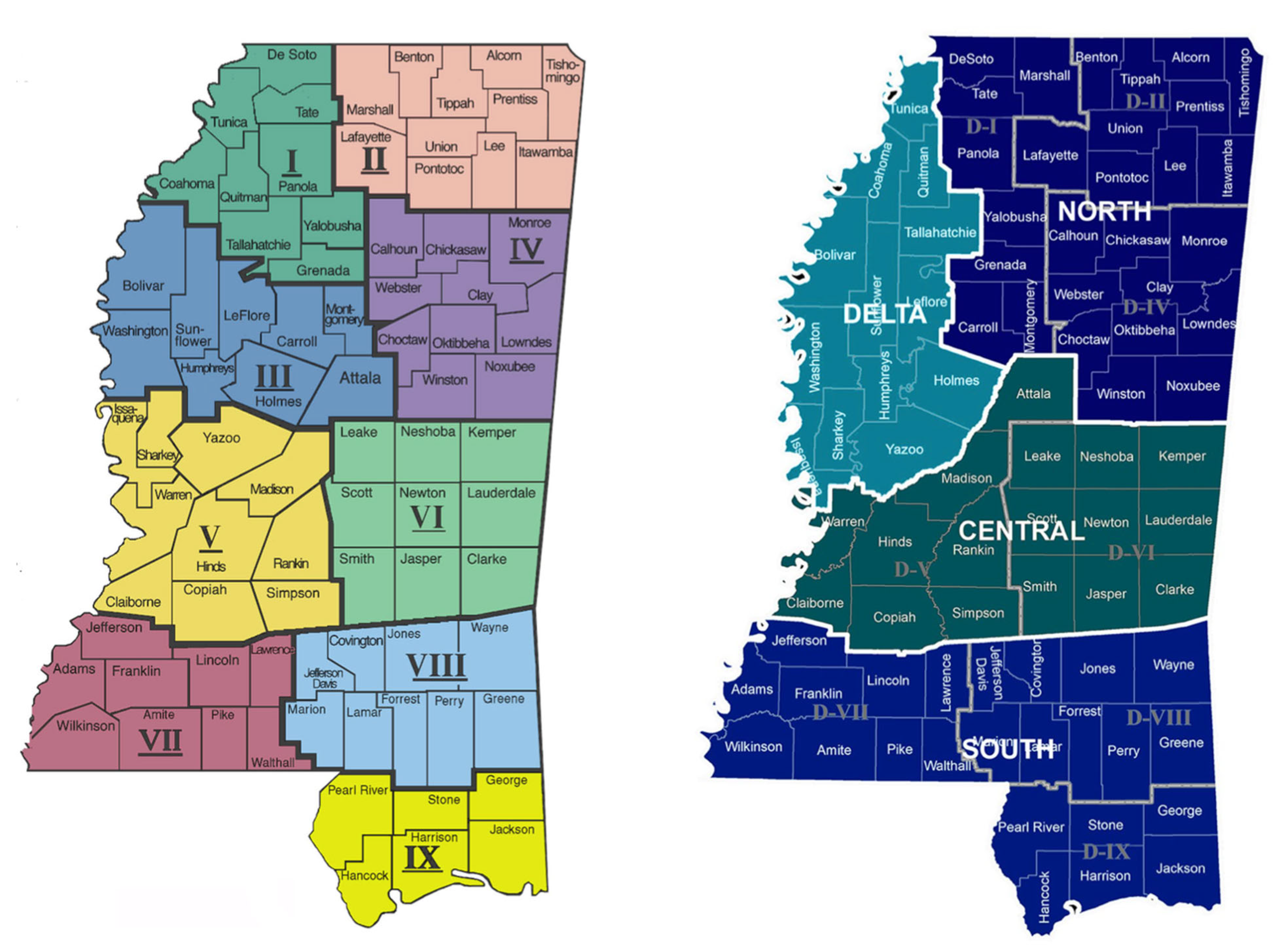

- Smith, H.; Seal, S.; Sullivan, D.C. Impact of Race, Poverty, Insurance Coverage and Resource Availability on Breast Cancer Across Geographic Regions of Mississippi. J. Miss. Acad. Sci. 2017, 62, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahnd, W.E.; McLafferty, S.L.; Sherman, R.L.; Klonoff-Cohen, H.; Farner, S.; Rosenblatt, K.A. Spatial Accessibility to Mammography Services in the Lower Mississippi Delta Region States. J. Rural. Health 2019, 35, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.S.; Young, C.; McKinney, S.; Simon Hawkins, O.S.; Roberson, C.; Udemgba, C.; Rogers, D.B.; Wells, J.; Lake, D.A.; Davis, D.; et al. Making Breast Screening Convenient: A Community-Based Breast Screening Event During a Historically Black University’s Homecoming Festivities. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 832–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.S.; Wells, J.; Duhe, R.J.; Shirley, T.; Lampkin, A.; Murphy, M.; Allen, T.C. The College of American Pathologists Foundation’s See, Test & Treat Program(R): An Evaluation of a One-Day Cancer Screening Program Implemented in Mississippi. J. Cancer Educ. 2022, 37, 1912–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Wiese, D.; Jatoi, I.; Jemal, A. State Variation in Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Incidence of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Among US Women. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mississippi State Department of Health. Annual Summary Selected Reportable Diseases Mississippi—2008. Available online: https://msdh.ms.gov/page/resources/3588.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Mississippi State Department of Health. Public Health Regions. Available online: https://msdh.ms.gov/page/resources/7322.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Qin, B.; Babel, R.A.; Plascak, J.J.; Lin, Y.; Stroup, A.M.; Goldman, N.; Ambrosone, C.B.; Demissie, K.; Hong, C.C.; Bandera, E.V.; et al. Neighborhood Social Environmental Factors and Breast Cancer Subtypes among Black Women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.; Waterman, P.D.; Testa, C.; Chen, J.T.; Krieger, N. Breast Cancer Incidence, Hormone Receptor Status, Historical Redlining, and Current Neighborhood Characteristics in Massachusetts, 2005–2015. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2022, 6, pkac016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, S.L.; Lee, S.J.; Tiro, J.A.; Xuan, L.; Ruiz, J.M.; Inrig, S. Residential racial segregation and mortality among black, white, and Hispanic urban breast cancer patients in Texas, 1995 to 2009. Cancer 2015, 121, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place. 2010, 16, 1038–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Agenor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnecke, R.B.; Campbell, R.T.; Vijayasiri, G.; Barrett, R.E.; Rauscher, G.H. Multilevel Examination of Health Disparity: The Role of Policy Implementation in Neighborhood Context, in Patient Resources, and in Healthcare Facilities on Later Stage of Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, Y.; Silva, A.; Rauscher, G.H. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Time to a Breast Cancer Diagnosis: The Mediating Effects of Health Care Facility Factors. Med. Care 2015, 53, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.I.; Zhu, W.; Onega, T.; Henderson, L.M.; Kerlikowske, K.; Sprague, B.L.; Rauscher, G.H.; O’Meara, E.S.; Tosteson, A.N.A.; Haas, J.S.; et al. Comparative Access to and Use of Digital Breast Tomosynthesis Screening by Women’s Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2037546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.A.; Cha, A.E. Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, January–June 2022; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2022; p. 21.

- Ward, E.; Halpern, M.; Schrag, N.; Cokkinides, V.; DeSantis, C.; Bandi, P.; Siegel, R.; Stewart, A.; Jemal, A. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008, 58, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.; Han, Y.; Lian, M.; Colditz, G.A.; Weber, J.D.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of Racial/Ethnic Differences in Treatment and Mortality Among Women With Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Clarke, C.A.; Lichtensztajn, D.Y.; Giordano, S.H. Delayed Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Among Patients With Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadigh, G.; Gray, R.J.; Sparano, J.A.; Yanez, B.; Garcia, S.F.; Timsina, L.R.; Sledge, G.W.; Cella, D.; Wagner, L.I.; Carlos, R.C. Breast cancer patients’ insurance status and residence zip code correlate with early discontinuation of endocrine therapy: An analysis of the ECOG-ACRIN TAILORx trial. Cancer 2021, 127, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mississippi State Department of Health. Mississippi Primary Care Needs Assessment. Available online: https://msdh.ms.gov/page/resources/7357.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Mississippi Cancer Registry. Age-Adjusted Cancer Mortality Rates by County in Mississippi, Female Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer-rates.info/ms/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2024–2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/2024/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2024.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=breast+cancer+and+georgia+state&filter=dates.2000-2024 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=breast+cancer+research+in+Alabama+State&size=200 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C25&as_ylo=2019&as_yhi=2025&q=Breast+cancer+and+Lousianaa&btnG= (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. An Ecosystem of Minority Health and Health Disparities Resources. Available online: https://hdpulse.nimhd.nih.gov/data-portal/physical/map?age=001&age_options=ageall_1&demo=01005&demo_options=res_seg_2&physicaltopic=100&physicaltopic_options=physical_2&race=00&race_options=raceall_1&sex=0&sex_options=sexboth_1&statefips=28&statefips_options=area_states (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Kruse-Diehr, A.J.; McDaniel, J.T.; Lewis-Thames, M.W.; James, A.S.; Yahaya, M. Racial Residential Segregation and Colorectal Cancer Mortality in the Mississippi Delta Region. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, K.M.; Udesky, J.O.; Rudel, R.A.; Brody, J.G. Environmental chemicals and breast cancer: An updated review of epidemiological literature informed by biological mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2018, 160, 152–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinomar, N.; Oskar, S.; Kehm, R.D.; Sahebzeda, S.; Terry, M.B. Environmental exposures and breast cancer risk in the context of underlying susceptibility: A systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 109346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godet, I.; Gilkes, D.M. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and treatment strategies for breast cancer. Integr. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2017, 4, 10-15761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors, Year | Location | Study Aim | Design | Outcome of Interest | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higginbotham et al., 2001 [10] | Mississippi | To investigate various aspects of cancer between rural and urban localities. | Cross-sectional | Stage of breast cancer diagnosis, access to screening programs | The study found that rural individuals were more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage compared to their urban counterparts. Additionally, rural residents in Mississippi, particularly rural Black women, face significant barriers to accessing early cancer detection programs and quality medical care. |

| Mitra & Faruque, 2004 [11] | Mississippi | To demonstrate the relationship between environmental chemicals and breast cancer incidence in the 82 counties in Mississippi. | Cross-sectional | Breast cancer incidence rate | The study identified counties with a higher breast cancer incidence compared to the state’s median rate in 1998. Six counties—Yazoo, Copiah, George, Forrest, Stone, and Hinds—had incidence rates 40% or higher than the state average. Additionally, Noxubee, Jefferson, Jones, Perry, Scott, Chickasaw, Madison, Yalobusha, Clay, Tishomingo, and Warren also had higher rates than the state median. Harrison, Hinds, Jackson, Forrest, Rankin, Jones, Lauderdale, Perry, DeSoto, and Scott counties had the highest levels of chemical emissions, with amounts 60% or higher than the state’s median emissions. Breast cancer incidence was significantly correlated with ammonia levels, as well as the minimum and maximum emissions from facilities within these counties. |

| DeSantis et al., 2008 [12] | United States, including Mississippi | To investigate temporal trends in age-standardized female breast cancer mortality rates across different states and racial groups. | Cross-sectional | Breast cancer mortality rate | The study found a decline in breast cancer mortality rates among White women in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC), with the timing of the decline varying by state. In contrast, among Black women, breast cancer mortality rates increased in two states (Arkansas and Mississippi) out of the 37 states analyzed, remained stable in 24 states, and decreased in 11 states. |

| Houston, 2009 [13] | Mississippi | To highlight the persistently high breast cancer mortality rate in Mississippi, particularly among Black women, and to advocate for improved prevention and early detection. | Opinion piece (Peer-reviewed) | breast cancer mortality rate, early detection | The study advocated for healthcare professionals to collaborate with patients to modify lifestyles, encourage preventive strategies, and rigorously follow the American Cancer Society’s guidelines for early breast cancer detection. |

| Wilson-Anderson et al., 2013 [14] | Mississippi Delta | To provide breast health education to women in two rural counties in the Mississippi Delta. | Quasi-experimental | Breast health knowledge and screening behaviors | The study found that rural Black women were receptive to primary health education on breast cancer and showed a certain level of adherence to recommended screenings. |

| Keeton et al., 2014 [15] | Mississippi | To test whether race and/or geography had an impact on the stage of breast cancer at the time of diagnosis. | Cross-sectional | Stage of breast cancer diagnosis | Women living in rural Mississippi were more likely to present with advanced-stage breast cancer compared to in situ or localized breast cancer, with rates of 4% for White women and 19% for Black women. Black women residing in urban Mississippi had 25% higher odds of being diagnosed in a later stage, while rural Black women had 47% higher odds compared to their urban and rural White counterparts, respectively. |

| Nichols et al., 2014 [16] | Mississippi | This study aimed to assess the impact of mammography resource availability on breast cancer incidence rates, stage at initial diagnosis, mortality rates, and mortality-to-incidence ratios across Mississippi. | Cross-sectional | Breast cancer incidence rates, stage at initial diagnosis, mortality rates, and mortality-to-incidence ratios | There were no statistically significant differences in breast cancer incidence rates between Black and White women in Mississippi. However, significant disparities were observed in mammography utilization, the percentage of advanced-stage diagnoses, mortality rates, and mortality-to-incidence ratios, with Black women experiencing worse outcomes in each category. No statistically significant correlations were found between breast cancer outcomes and the availability of mammography facilities. However, mammography use was negatively correlated with the likelihood of advanced-stage diagnosis at initial presentation. |

| Fortune, 2015 [17] | Mississippi | This study examined the impact of the Breast and Cervical Cancer Program (BCCP) on the stage at which breast cancer is diagnosed among women in Mississippi. | Retrospective cohort | Stage of breast cancer diagnosis | Findings from this study revealed that increased screenings led to a higher number of breast cancer diagnoses. However, women enrolled in the BCCP continued to be diagnosed in later stages of the disease. |

| Mayfield-Johnson et al., 2016 [18] | Mississippi Delta | To increase the relatively low screening rate for African American women in the Mississippi Delta through a collaborative partnership and to decrease health disparities in breast cancer through increased awareness of self-early detection methods, leveraging resources to provide mammography screenings, and adequate follow-up with services and treatment for abnormal findings. | Cross-sectional | Breast cancer screening | In summary, 86.47% of the participants in this study were aged 40 years or older and met the clinical guidelines recommending a mammogram. However, 40.26% reported never having undergone the screening procedure, and 37.29% stated that it had been more than two years since their last mammogram, despite 93.06% having prior knowledge of mammograms. A majority of participants cited expense and access as difficulties to mammogram participation. |

| Fortune, 2017 [19] | Mississippi | To examine the impact of social determinants on the stage at which breast cancer is diagnosed, with a specific focus on race, income, and lack of health insurance. | Cross-sectional | Stage of breast cancer diagnosis | The study showed that Black women in Mississippi were disproportionately diagnosed in a later stage of breast cancer as opposed to an early stage. Only race and health insurance directly affected late-stage diagnosis. |

| Smith et al., 2017 [20] | Mississippi | To investigate the incidence of breast cancer across various health districts in Mississippi concerning healthcare disparities and accessibility. | Cross-sectional | Breast cancer incidence rate and mortality rate | The incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer among Black women in Districts VII and III are significantly higher than those in the other seven health districts of Mississippi. Additionally, Black women were diagnosed at an older age and a later stage of the disease, according to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program staging, compared to White women. Moreover, the majority of Black women in these districts faced socioeconomic disadvantages, including higher poverty rates and lower educational attainment. |

| Zahnd et al., 2019 [21] | Lower Mississippi Delta Region states | To assess and characterize spatial accessibility to mammography services across eight states in the Lower Mississippi Delta Region (LMDR). | Cross-sectional | Access to mammography services | The study found clusters of low spatial access in parts of the Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee Delta. |

| Williams et al., 2020 [22] | Mississippi | The study aimed to provide free clinical breast exams (CBEs) and breast cancer risk assessments to non-elderly African American women through a community-based breast cancer screening event. | Cross-sectional | Breast cancer screening | During the event, two healthcare providers performed clinical breast exams for 26 Black women and provided tailored risk-reduction counseling. Nearly one-third of the women screened reported never having undergone a breast cancer screening before. The authors concluded that events like this are an effective way to reach women who have never received any form of breast cancer screening. |

| Williams et al., 2022 [23] | Mississippi | To implement See, Test & Treat, a cancer screening and education program designed to improve access to cancer screening for underserved women in the Jackson Metropolitan Area. | Cross-sectional | Breast cancer screening | A total of 57 women received a mammogram. Participants reported that the program positively influenced their intentions to adopt healthier behaviors, with the majority stating they would perform regular self-breast exams and continue receiving routine mammograms. |

| Sung et al., 2023 [24] | United States, including Mississippi | To measure racial and ethnic disparities in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) incidence rates both between and within populations across US states. | Retrospective cohort study | Triple-negative breast cancer incidence rate | The study reported substantial racial disparities in TNBC incidence across states, showing that Black women in Mississippi, Delaware, Missouri, and Louisiana had the highest rates among all states and racial groups. |

| Authors | Quality Appraisal for Cross-Sectional Studies | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Decision | ||||

| Higginbotham et al., 2001 [10] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Mitra & Faruque, 2004 [11] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Include | |||

| DeSantis et al., 2008 [12] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Keeton et al., 2014 [15] | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Nichols et al., 2014 [16] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Mayfield-Johnson et al., 2016 [18] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Fortune, 2017 [19] | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Smith et al., 2017 [20] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Zahnd et al., 2019 [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Williams et al., 2020 [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Williams et al., 2022 [23] | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Include | |||

| Note. Q1: Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? Q2: Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? Q3: Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? Q4: Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? Q5: Were confounding factors identified? Q6: Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? Q7: Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? Q8: Was appropriate statistical analysis used? Abbreviation: Y = Yes, N = No, U = Unclear, N/A = Not Applicable. | ||||||||||||

| Authors | Quality Appraisal for Cohort Studies | |||||||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Decision | |

| Fortune, 2015 [17] | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Include |

| Sung et al., 2023 [24] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Note. Q1: Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population? Q2: Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups? Q3: Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? Q4: Were confounding factors identified? Q5: Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? Q6: Were the groups/participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or at the moment of exposure)? Q7: Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? Q8: Was the follow up time reported and sufficient to be long enough for outcomes to occur? Q9: Was follow up complete, and if not, were the reasons to loss to follow up described and explored? Q10: Were strategies to address incomplete follow up utilized? Q11: Was appropriate statistical analysis used? Abbreviation: Y = Yes, N = No, U = Unclear, N/A = Not Applicable. | ||||||||||||

| Authors | Quality Appraisal for Quasi-Experimental Study | |||||||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Decision | |||

| Wilson-Anderson et al., 2013 [14] | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include | ||

| Note. Q1: Is it clear in the study what is the “cause” and what is the “effect” (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? Q2: Was there a control group? Q3: Were participants included in any comparisons similar? Q4: Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? Q5: Were there multiple measurements of the outcome, both pre and post the intervention/exposure? Q6: Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? Q7: Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? Q8: Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed? Q9: Was appropriate statistical analysis used? Abbreviation: Y = Yes, N = No. | ||||||||||||

| Authors | Quality Appraisal for Opinion Piece | |||||||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Decision | ||||||

| Houston, 2009 [13] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include | |||||

| Note. Q1: Is the source of the opinion clearly identified? Q2: Does the source of opinion have standing in the field of expertise? Q3: Are the interests of the relevant population the central focus of the opinion? Q4: Does the opinion demonstrate a logically defended argument to support the conclusions drawn? Q5: Is there reference to the extant literature? Q6: Is any incongruence with the literature/sources logically defended? Abbreviation: Y = Yes. | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barsha, R.A.A.; Miller-Kleinhenz, J. Left Behind: The Unmet Need for Breast Cancer Research in Mississippi. Cancers 2025, 17, 1652. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101652

Barsha RAA, Miller-Kleinhenz J. Left Behind: The Unmet Need for Breast Cancer Research in Mississippi. Cancers. 2025; 17(10):1652. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101652

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarsha, Rifath Ara Alam, and Jasmine Miller-Kleinhenz. 2025. "Left Behind: The Unmet Need for Breast Cancer Research in Mississippi" Cancers 17, no. 10: 1652. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101652

APA StyleBarsha, R. A. A., & Miller-Kleinhenz, J. (2025). Left Behind: The Unmet Need for Breast Cancer Research in Mississippi. Cancers, 17(10), 1652. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101652