A Systematic Review Defining Early Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Identifying Treatment

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

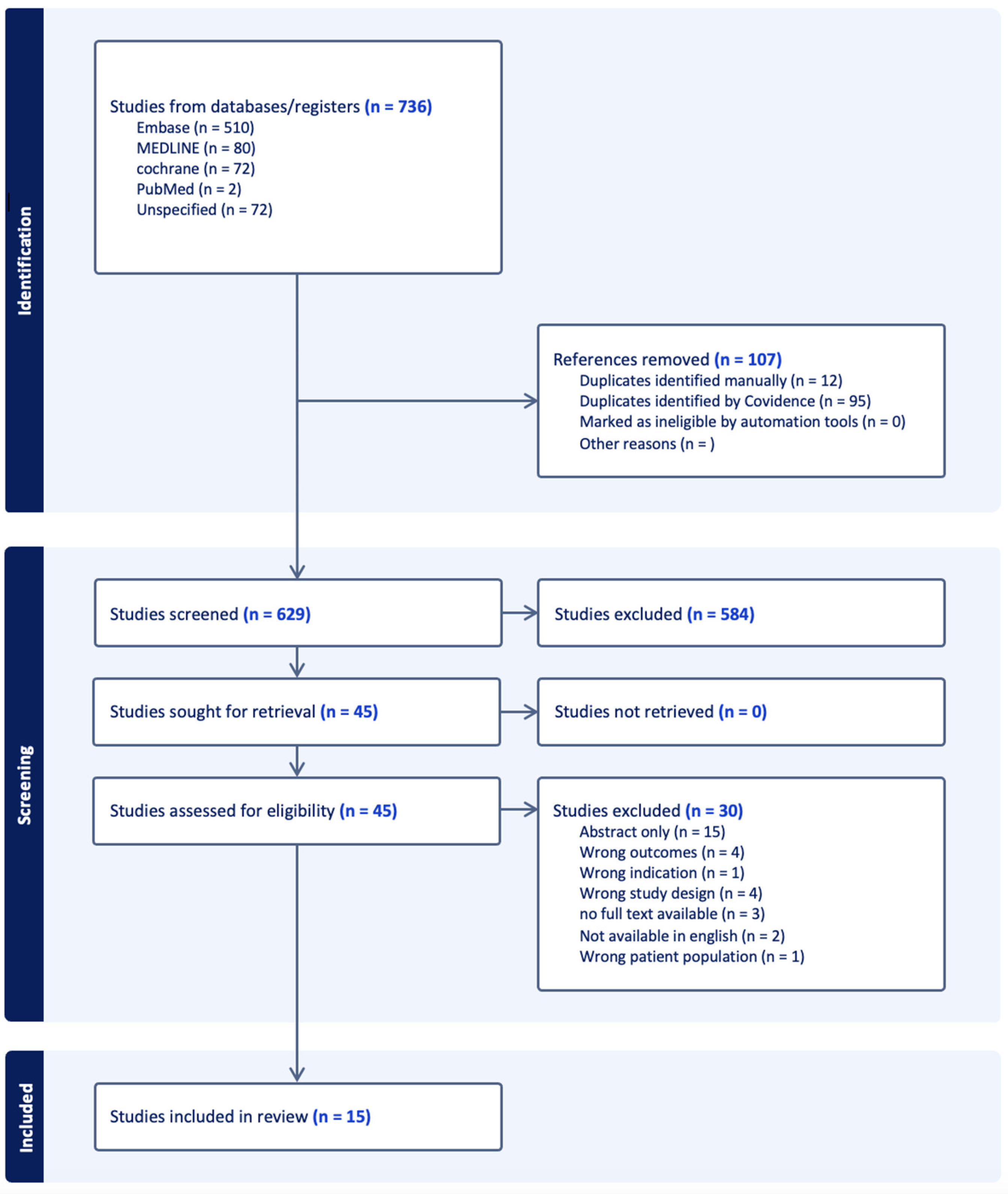

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Defining Early Anal Cancer

3.2. Chemoradiation vs. Radiation Alone

3.3. Chemoradiation Alone

3.4. Different Chemotherapy Regimens

3.5. Surgery with Chemoradiation

3.6. Surgery Alone

3.7. Other

3.8. GRADE Criteria

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| GRADE | Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| SISCCA | Superficially Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| SCC | squamous cell carcinoma |

| HPV | human papilloma virus |

| ANCHOR | Anal HSIL/Cancer Outcomes Research |

| HSIL | high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| HRA | high-resolution anoscopy |

| T | stage, tumor size |

| N | stage, nodal involvement |

| RT | radiation therapy, radiotherapy |

| CRT | chemoradiation |

| APR | abdominoperineal resection |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| MMC | mitomycin C |

| NCDB | National Cancer Database |

| FM | 5-FU + mitomycin |

| CM | capecitabine + mitomycin |

| SEER | Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results |

| OS | overall survival |

| LRC | locoregional control rates |

| CFS | colostomy-free survival |

| CSS | cancer-specific survival |

| RFS | recurrence-free survival |

| EBRT | external beam radiation therapy |

| DFS | disease-free survival |

| ACSS | anal cancer-specific survival |

| R | residual tumor classification |

| INRT | inguinal node radiation therapy |

| pSCC | perianal squamous cell carcinoma |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| AC | anal canal |

| PA | perianal |

| mASCARA | Multinational Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Registry and Audit |

Appendix A. Supplemental Text

- Full search strategy:

- ((‘early diagnosis’/exp OR ‘mass screening’/exp OR (((early OR earlier OR earliest OR routin*) NEAR/3 (screen* OR detect* OR diagnos* OR discover* OR stag*)) OR (mass NEAR/3 screen*))) AND ((((((anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus) NEAR/5 (cancer* OR neoplas* OR tumo$r* OR malig* OR carcino* OR adenocarcin* OR melanom* OR verge)) OR siscca) AND (anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus OR cancer* OR neoplas* OR tumo$r* OR malig* OR carcino* OR adenocarcin* OR melanom* OR verge OR siscca) NEAR/5 (early OR earlier OR stag* OR detect* OR microinvas* OR invas* OR ‘excision only’ OR ‘only excision’ OR ‘excision alone’ OR t1 OR ‘carcinoma in situ’ OR tis OR ‘stage i’ OR ‘stage i?’ OR ‘stage 1’ OR ‘stage 1?’ OR ‘stage one’)) AND (treat* OR therap* OR pharmacother* OR chemother* OR chemoradiat* OR surg* OR excis* OR radiother* OR manag* OR interven* OR protocol*)) OR ((((((anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus) NEAR/5 (cancer* OR neoplas* OR tumo$r* OR malig* OR carcino* OR adenocarcin* OR melanom* OR verge)) OR siscca) AND (anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus OR cancer* OR neoplas* OR tumo$r* OR malig* OR carcino* OR adenocarcin* OR melanom* OR verge OR siscca) NEAR/5 (early OR earlier OR stag* OR detect* OR microinvas* OR invas* OR ‘excision only’ OR ‘only excision’ OR ‘excision alone’ OR t1 OR ‘carcinoma in situ’ OR tis OR ‘stage i’ OR ‘stage i?’ OR ‘stage 1’ OR ‘stage 1?’ OR ‘stage one’)) AND (treat* OR therap* OR pharmacother* OR chemother* OR chemoradiat* OR surg* OR excis* OR radiother* OR manag* OR interven* OR protocol*)) AND (treat* OR therap* OR pharmacother* OR chemother* OR chemoradiat* OR surg* OR excis* OR radiother* OR manag* OR interven* OR protocol) NEAR/5 (anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus))) AND [embase]/lim) NOT ((‘early diagnosis’/exp OR ‘mass screening’/exp OR (((early OR earlier OR earliest OR routin*) NEAR/3 (screen* OR detect* OR diagnos* OR discover* OR stag*)) OR (mass NEAR/3 screen*))) AND ((((((anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus) NEAR/5 (cancer* OR neoplas* OR tumo$r* OR malig* OR carcino* OR adenocarcin* OR melanom* OR verge)) OR siscca) AND (anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus OR cancer* OR neoplas* OR tumo$r* OR malig* OR carcino* OR adenocarcin* OR melanom* OR verge OR siscca) NEAR/5 (early OR earlier OR stag* OR detect* OR microinvas* OR invas* OR ‘excision only’ OR ‘only excision’ OR ‘excision alone’ OR t1 OR ‘carcinoma in situ’ OR tis OR ‘stage i’ OR ‘stage i?’ OR ‘stage 1’ OR ‘stage 1?’ OR ‘stage one’)) AND (treat* OR therap* OR pharmacother* OR chemother* OR chemoradiat* OR surg* OR excis* OR radiother* OR manag* OR interven* OR protocol*)) OR ((((((anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus) NEAR/5 (cancer* OR neoplas* OR tumo$r* OR malig* OR carcino* OR adenocarcin* OR melanom* OR verge)) OR siscca) AND (anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus OR cancer* OR neoplas* OR tumo$r* OR malig* OR carcino* OR adenocarcin* OR melanom* OR verge OR siscca) NEAR/5 (early OR earlier OR stag* OR detect* OR microinvas* OR invas* OR ‘excision only’ OR ‘only excision’ OR ‘excision alone’ OR t1 OR ‘carcinoma in situ’ OR tis OR ‘stage i’ OR ‘stage i?’ OR ‘stage 1’ OR ‘stage 1?’ OR ‘stage one’)) AND (treat* OR therap* OR pharmacother* OR chemother* OR chemoradiat* OR surg* OR excis* OR radiother* OR manag* OR interven* OR protocol*)) AND (treat* OR therap* OR pharmacother* OR chemother* OR chemoradiat* OR surg* OR excis* OR radiother* OR manag* OR interven* OR protocol) NEAR/5 (anus* OR anal OR anally OR anorect* OR perianal* OR perianus))) AND [medline]/lim).

References

- Islami, F.; Ferlay, J.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A. International trends in anal cancer incidence rates. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Franceschi, S.; Clifford, G.M. Human papillomavirus types from infection to cancer in the anus, according to sex and HIV status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, G.M.; Georges, D.; Shiels, M.S.; Engels, E.A.; Albuquerque, A.; Poynten, I.M.; de Pokomandy, A.; Easson, A.M.; Stier, E.A. A meta-analysis of anal cancer incidence by risk group: Toward a unified anal cancer risk scale. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, M.; Bailoni, A.; Mariani, F.; Granai, M.; Calomino, N.; Mancini, V.; D’Antiga, A.; Montagnani, F.; Tumbarello, M.; Lazzi, S.; et al. Prevalence, Incidence and Predictors of Anal HPV Infection and HPV-Related Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions in a Cohort of People Living with HIV. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palefsky, J.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Jay, N.; Goldstone, S.E.; Darragh, T.M.; Dunlevy, H.A.; Rosa-Cunha, I.; Arons, A.; Pugliese, J.C.; Vena, D.; et al. Treatment of Anal High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions to Prevent Anal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junejo, M.H.; Oyebanji, O.I.; Wang, B.; Cappello, C.; Wait, B.; Farrow, E.; Nathan, M.; Bowring, J.; Cuming, T. Early detection of anal squamous cell carcinoma with the use of high-resolution anoscopy. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 50, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh, T.M.; Colgan, T.J.; Thomas Cox, J.; Heller, D.S.; Henry, M.; Luff, R.D.; McCalmont, T.; Nayar, R.; Palefsky, J.M.; Stoler, M.H.; et al. The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: Background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2013, 32, 76–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, G.; Daniel, R.; McKechnie, T.; Levine, O.; Eskicioglu, C. Radiotherapy alone versus chemoradiotherapy for stage I anal squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2021, 36, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, H.; Zwahlen, M.; Trelle, S.; Malcomson, L.; Kochhar, R.; Saunders, M.P.; Sperrin, M.; van Herk, M.; Sebag-Montefiore, D.; Egger, M.; et al. Nodal stage migration and prognosis in anal cancer: A systematic review, meta-regression, and simulation study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1348–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczewski, L.M.; Faski, J.; Nelson, H.; Gollub, M.J.; Eng, C.; Brierley, J.D.; Palefsky, J.M.; Goldberg, R.M.; Washington, M.K.; Asare, E.A.; et al. Survival outcomes used to generate version 9 American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for anal cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigro, N.D.; Seydel, H.G.; Considine, B.; Vaitkevicius, V.K.; Leichman, L.; Kinzie, J.J. Combined preoperative radiation and chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Cancer 1983, 51, 1826–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigro, N.D.; Vaitkevicius, V.K.; Considine, B., Jr. Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: A preliminary report. Dis. Colon. Rectum 1974, 17, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigro, N.D. An evaluation of combined therapy for squamous cell cancer of the anal canal. Dis. Colon. Rectum 1984, 27, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, P.; Deantonio, L.; Muirhead, R.; Gilbert, A.; Gambacorta, M.A.; Kronborg, C.; Guren, M.G. Optimising chemoradiotherapy in anal cancer. ESMO Gastrointest. Oncol. 2025; in Press. [Google Scholar]

- UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party. Epidermoid anal cancer: Results from the UKCCCR randomised trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, and mitomycin. Lancet 1996, 348, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelink, H.; Roelofsen, F.; Eschwege, F.; Rougier, P.; Bosset, J.F.; Gonzalez, D.G.; Peiffert, D.; van Glabbeke, M.; Pierart, M. Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer: Results of a phase III randomized trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiotherapy and Gastrointestinal Cooperative Groups. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 2040–2049. [Google Scholar]

- Ajani, J.A.; Winter, K.A.; Gunderson, L.L.; Pedersen, J.; Benson, A.B.; Thomas, C.R.; Mayer, R.J.; Haddock, M.; Rich, T.A.; Willett, C. Fluorouracil, mitomycin, and radiotherapy vs fluorouracil, cisplatin, and radiotherapy for carcinoma of the anal canal: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008, 299, 1914–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.D.; Glynne-Jones, R.; Meadows, H.M.; Cunningham, D.; Myint, A.S.; Saunders, M.P.; Maughan, T.; McDonald, A.; Essapen, S.; Leslie, M.; et al. Mitomycin or cisplatin chemoradiation with or without maintenance chemotherapy for treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus (ACT II): A randomised, phase 3, open-label, 2 × 2 factorial trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachnic, L.A.; Winter, K.; Myerson, R.J.; Goodyear, M.D.; Willins, J.; Esthappan, J.; Haddock, M.G.; Rotman, M.; Parikh, P.J.; Safran, H.; et al. RTOG 0529: A phase 2 evaluation of dose-painted intensity modulated radiation therapy in combination with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin-C for the reduction of acute morbidity in carcinoma of the anal canal. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2013, 86, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Guren, M.G.; Khan, K.; Brown, G.; Renehan, A.G.; Steigen, S.E.; Deutsch, E.; Martinelli, E.; Arnold, D. Anal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.B.; Venook, A.P.; Al-Hawary, M.M.; Azad, N.; Chen, Y.J.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cohen, S.; Cooper, H.S.; Deming, D.; Garrido-Laguna, I.; et al. Anal Carcinoma, Version 2.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2023, 21, 653–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry-Lawhorn, J.M.; Palefsky, J.M. Progression of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions to anal squamous cell carcinoma and clinical management of anal superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Semin. Colon. Rectal Surg. 2017, 28, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfa-Wali, M.; Dalla Pria, A.; Nelson, M.; Tekkis, P.; Bower, M. Surgical excision alone for stage T1 anal verge cancers in people living with HIV. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 42, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arana, R.; Flejou, J.F.; Si-Mohamed, A.; Bauer, P.; Etienney, I. Clinicopathological and virological characteristics of superficially invasive squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus. Colorectal Dis. 2015, 17, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, A.G.; Guren, M.G.; Wanderås, E.H.; Frykholm, G.; Tveit, K.M.; Wilsgaard, T.; Dahl, O.; Balteskard, L. Chemoradiotherapy of anal carcinoma: Survival and recurrence in an unselected national cohort. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 83, e173–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, B.; Menzel, M.; Breucha, G.; Bamberg, M.; Weinmann, M. Postoperative versus definitive chemoradiation in early-stage anal cancer. Results of a matched-pair analysis. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2012, 188, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goksu, S.Y.; Ozer, M.; Kazmi, S.M.A.; Aguilera, T.A.; Ahn, C.; Hsiehchen, D.; Sanjeevaiah, A.; Maxwell, M.C.; Beg, M.S.; Sanford, N.N. Racial Disparities in Time to Treatment Initiation and Outcomes for Early Stage Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 43, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, D.L.; Jayakrishnan, T.T.; Vannatter, B.L.; Monga, D.K.; Finley, G.G.; McCormick, J.T.; Kirichenko, A.V.; Wegner, R.E. Chemotherapy use in early stage anal canal squamous cell carcinoma and its impact on long-term overall survival. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2021, 27, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabarriti, R.; Brodin, N.P.; Ohri, N.; Narang, R.; Huang, R.; Chuy, J.W.; Rajdev, L.N.; Kalnicki, S.; Guha, C.; Garg, M.K. Human papillomavirus, radiation dose and survival of patients with anal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 1745–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; von der Grun, J.; Rodel, C.; Fokas, E. Management of anal cancer patients—A pattern of care analysis in German-speaking countries. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, R.D.; Wan, D.D.; Schellenberg, D.; Lim, H.J. A comparison between 5-fluorouracil/mitomycin and capecitabine/mitomycin in combination with radiation for anal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2016, 7, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suradkar, K.; Pappou, E.E.; Lee-Kong, S.A.; Feingold, D.L.; Kiran, R.P. Anal canal squamous cell cancer: Are surgical alternatives to chemoradiation just as effective? Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2018, 33, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, I.; Osborn, V.; Lee, A.; Katsoulakis, E.; Kavi, A.; Choi, K.; Safdieh, J.; Schreiber, D. Survival benefits and predictors of use of chemoradiation compared with radiation alone for early stage (T1-T2N0) anal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019, 10, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilli, T.; Betz, M.; Bieri, S.; Ris, F.; Roche, B.; Roth, A.D.; Allal, A.S. Elective inguinal node irradiation in early-stage T2N0 anal cancer: Prognostic impact on locoregional control. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2013, 87, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilli, T.; Schick, U.; Ozsahin, M.; Gervaz, P.; Roth, A.D.; Allal, A.S. Node-negative T1-T2 anal cancer: Radiotherapy alone or concomitant chemoradiotherapy? Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 102, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccabe, T.A.; Parwaiz, I.; Longman, R.J.; Thomas, M.G.; Messenger, D.E. Outcomes following local excision of early anal squamous cell carcinomas of the anal canal and perianal margin. Colorectal Dis. 2021, 23, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogden, D.R.L.; Kontovounisios, C.; Chong, I.; Tait, D.; Warren, O.J.; Bower, M.; Tekkis, P.; Mills, S.C. Local excision and treatment of early node-negative anal squamous cell carcinomas in a highly HIV prevalent population. Tech. Coloproctology 2021, 25, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jephcott, C.R.; Paltiel, C.; Hay, J. Quality of life after non-surgical treatment of anal carcinoma: A case control study of long-term survivors. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 16, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, R.N.; Gaskins, M.; Avila Valle, G.; Budach, V.; Koswig, S.; Mosthaf, F.A.; Raab, H.R.; Rödel, C.; Nast, A.; Siegel, R.; et al. State of the art treatment for stage I to III anal squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 157, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, L.; Martini, S.; Solla, S.D.; Vigna Taglianti, R.; Olivero, F.; Gianello, L.; Reali, A.; Merlotti, A.M.; Franco, P. Nodal Elective Volume Selection and Definition during Radiation Therapy for Early Stage (T1–T2 N0 M0) Perianal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Narrative Clinical Review and Critical Appraisal. Cancers 2023, 15, 5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaru, Y.; Oka, S.; Tanaka, S.; Ninomiya, Y.; Asayama, N.; Shigita, K.; Nishiyama, S.; Hayashi, N.; Arihiro, K.; Chayama, K. Early squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal resected by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2015, 9, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PLATO—PersonaLising Anal Cancer radioTherapy dOse. 2016. Available online: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/application-summaries/research-summaries/plato-personalising-anal-cancer-radiotherapy-dose/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Sebag-Montefiore, D.; Adams, R.; Bell, S.; Berkman, L.; Gilbert, D.C.; Glynne-Jones, R.; Goh, V.; Gregory, W.; Harrison, M.; Kachnic, L.A.; et al. The Development of an Umbrella Trial (PLATO) to Address Radiation Therapy Dose Questions in the Locoregional Management of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016, 96, E164–E165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Publication Year | Study Design | Years of Inclusion | Number of Institutions | Number of Participants | Anal Cancer Location and Stages | Treatments Studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfa- Wali et al. [24] | 2016 | retrospective cohort | 1986–2015 | National Centre for HIV malignancies at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London | 15 | anal verge, T1N0M0 | local excision only, surgical margin of >1 cm |

| Arana et al. [25] | 2015 | retrospective review | Jan 2007–December 2009 | 1—Diaconesses Hospital | 17 | T1N0M0- superficially invasive or invasive | local excision: margin of >2 mm for anal canal cancers and >1 cm for anal margin |

| Bentzen et al. [26] | 2011 | retrospective cohort | July 2000–June 2007 | 5—University Hospital of Northern Norway, Oslo University Hospital, Haukeland University Hospital, Olav University Hospital, University of Tromsø | 328 | nonmetastatic squamous cell carcinoma | definitive CRT |

| Berger et al. [27] | 2012 | retrospective cohort | 1998–2008 | 1—University of Tuebin | 40 | T1-2N0 anal cancer | surgery with adjuvant CRT vs. primary chemoradiation |

| Goksu et al. [28] | 2020 | retrospective database (NCDB) | 2004–2016 | Database | 9311 | stage I-II squamous cell cancer | CRT |

| Huffman et al. [29] | 2021 | retrospective database (NCDB) | 2004–2016 | Database | 2959 | cT1N0M0 squamous cell of anal canal | EBRT with and without CMT |

| Kabarriti et al. [30] | 2019 | retrospective database (NCDB) | 2008–2014 | Database | 5927 | nonmetastatic squamous cell carcinoma | differences in radiation dose |

| Martin et al. [31] | 2020 | pattern of care survey | 101 institutions (28% response rate—sent to 361) | ||||

| Piexoto et al. [32] | 2016 | retrospective review | 1998–2013 | British Columbia Cancer Agency | 300 | stages I-III SCC in 243/300 (81%) | CRT with 5-FU + mitomycin (FM) vs. capecitabine + mitomycin (CM) |

| Suradkar et al. [33] | 2017 | retrospective database (SEER) | 2004–2013 | Database | 3307 | anal canal | RT vs. local excision vs. APR vs. APR after RT |

| Youssef et al. [34] | 2019 | retrospective database (NCDB) | 2004–2014 | Database | 4564 | T1-2N0M0, 33.5% with T1 and 66.5% with T2 | CRT vs. RT alone |

| Zilli et al. [35] | 2013 | retrospective cohort | 1976–2008 | 1—Geneva University Hospital | 116 | T2N0M0 | elective inguinal node radiation therapy in those treated with RT alone or CRT |

| Zilli et al. [36] | 2011 | retrospective cohort | 1976–2008 | 1—Geneva University Hospital | 146 | T1-2N0M0 anal cancer, anal canal and anal margin | RT alone vs. CRT with 5-FU/ mitomycin |

| MacCabe et al. [37] | 2020 | retrospective cohort | 2007–2019 | 1—University Hospitals Bristol and Weston | 39 | T1-T2N0M0, perianal and anal canal | local excision alone |

| Brogden et al. [38] | 2021 | retrospective cohort | 2000–2020 | 1—NHS Foundation Trusts | 94 | T1-T3N0M0 | CRT vs. RT vs. local excision alone vs. APR vs. defunctioning stoma |

| Authors | Age | Sex | Race | HIV Positivity | HPV Positivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfa-Wali et al. [24] | mean 49 years | NA | NA | 15/15 (100%) | NA |

| Arana et al. [25] | median 47.7 years | female 5/17 (29.5%) | NA | 10/17 (58.8%) | 17/17 (100%) |

| Bentzen et al. [26] | median 63 years | NA | NA | 6/328 (2.0%) | NA |

| Berger et al. [27] | median 58 years | female 25/40 (67.0%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Goksu et al. [28] | mean 58 years | female 6114/9311 (65.6%) | 8451/9311 White (90.6%) | NA | NA |

| Huffman et al. [29] | median age 58 | female 2019/2959 (68.2%) | 2722/2959 (92.0%) White | NA | NA |

| Kabarriti et al. [30] | mean 57.3 for HPV tested group | female 3466/5927 (58.5%) | 5002/5927 (85.3%) White | NA | 3523/5927 (59.4%) |

| Martin et al. [31] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Peixoto et al. [32] | median age 58 | female 195/300 (65%) | NA | 13/300 (4.0%) | NA |

| Suradkar et al. [33] | RT: mean 60 years Local excision:57 years APR: 64 years RT + APR: 56 years | RT: female 1884/2772 (68.0%) Local excision: female 192/382 (50.3%) APR: female 36/77 (46.8%) RT + APR: female 46/76 (60.5%) | RT: 86.8% White Local excision: 81.7% White APR: 88.3% White RT + APR: 93.4% White | NA | NA |

| Youssef et al. [34] | over 60 years old, 68.7% in CRT and 68.4% in RT | NA | White 90.5% in CRT group and 84.5% in RT | NA | NA |

| Zilli et al. (2013) [35] | median with INRT 65 years, without INRT 71 years | female 84/116 (72.4%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Zilli et al. (2011) [36] | median 66 years | female 105/146 (72.0%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Maccabe et al. [37] | median 62 years | female 29/42 (69.0%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Brogden et al. [38] | mean 53.1 years | female 16/94 (17.0%) | NA | 57/94 (60.6%) | NA |

| Author | Early Anal Cancer Definition |

|---|---|

| Alfa- Wali et al. [24] | T1N0M0 |

| Berger et al. [27] | T1-2N0 |

| Goksu et al. [28] | T1-T3N0, T1-T2N1M0 |

| Kabarriti et al. [30] | T1-2N0 |

| Martin et al. [31] | cT1-2N0M0 |

| Youssef et al. [34] | cT1-2N0M0 |

| Zilli et al. (2013) [35] | T1-2N0 |

| Zilli et al. (2011) [36] | T1-2N0 |

| Maccabe et al. [37] | T1-2N0 |

| Brogden et al. [38] | T1-T3N0, T1-T2N1M0 |

| Author | Number of Participants (Years of Study) | Anal Cancer Location and Stages Included | Treatments Studied | Overall Survival (OS) | Locoregional Control Rates (LRC) | Colostomy-Free Survival (CFS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huffman et al. [29] | 2959 (2004–2016) | cT1N0M0 squamous cell of anal canal | CRT with and without CMT | 5-year OS: 86% with CRT, 65% with RT only | ||

| Youssef et al. [34] | 4564 (2004–2014) | T1-2N0M0, 33.5% with T1 and 66.5% with T2 | CRT vs. RT alone | 5-year OS: 86.6% CRT and 79.1% RT, p = 0.114 T1 OS: 90.3% with CRT and 84.7% RT T2 OS: 84.7% CRT and 72.8% RT, p < 0.0001 | ||

| Zilli et al. [36] | 146 (1976–2008) | T1-2N0M0 anal cancer | RT alone vs. CRT with 5-FU/mitomycin Median follow-up 62.5 months | Estimated 5-year actuarial OS for all patients: 75.4% +/− 3.9% | 5-year LRC for RT alone: 75.5% +/− 6% 5 year LRC for CRT: 88.5% +/− 4.5% 5-year LRC for T1 tumors: 92.9 ± 6.9% 5-year LRC for T2 tumors: 78.5 ± 4.1% | Entire cohort: 82.4% +/− 3.5% RT only: 79.9% +/− 5.6% CRT only: 84.6% +/− 4.5%, p = 0.567 |

| Author | Number of Participants | Anal Cancer Location and Stages Included | Treatments Studied | Treatment Sequence | Relapses | Overall Survival (OS) | Cancer-Specific Survival (CSS) | Recurrence-Free Survival (RFS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bentzen et al. [26] | 328 | nonmetastatic squamous cell carcinoma | CRT only with RT (EBRT) | T1-T2N0 tumors: EBRT with 5-FU and mitomycin T3-T4 or N1 + 2: courses of neoadjuvant chemo with cisplatin and 5FU and concurrent CRT with EBRT | recurrence: 73/328 (24%), recurrence treated with surgical resection in 32, palliative intent in 40 patients | 3-year OS = 79% 5-year OS = 66% | 3-year CSS = 84% 5-year CSS = 75% | 3-year RFS = 79% 5-year RFS = 74% |

| Goksu et al. [28] | 9311 | stage I–II ASCC | CRT only | 5-year OS for African American patients: 71% vs. White 75%, p < 0.001 |

| Author | Number of Participants | Anal Cancer Location and Stages Included | Treatments Studied | Results | Cancer-Specific Survival (CSS) | Disease-Free Survival (DFS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peixoto et al. [32] | 300 | stages I–III ASCC | chemoradiation with 5-FU + mitomycin (FM) (194 patients, 64.6%) vs. capecitabine + mitomycin (CM) (106 patients, 35.3%) | only HIV status, clinical T size, and clinical N status were prognostic factors for DFS and ACSS | 2-year anal cancer-specific survival: 88.7% CM (95% CI [81.8–95.5%]) and 87.5% (95%CI 82.8–92.2]) FM p = 0.839 | 79.7% (95% CI [71.7–88.3]) for CM and 78.8% (95%CI [73–84.6%]) for FM p = 0.663 |

| Author | Number of Participants | Anal Cancer Location and Stages Included | Treatments Studied | Overall Survival (OS) | Cancer-Specific Survival (CSS) | Locoregional Control Rates (LRC) | Colostomy-Free Survival (CFS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berger et al. [27] | 40 | T1-2N0 anal cancer | adjuvant CRT vs. primary CRT | 5-year OS: 90% 10-year OS: 84.7% 5-year OS: surgery then adjuvant CRT group 94.7% 5-year OS: CRT group 86.5 p = 0.36 | for surgery with adjuvant CRT-95% CRT-100% p = 0.32 | 5-year CFS 95% in both groups | |

| Suradkar et al. [33] | 3307 | anal canal; all stages included 1530 patients with stage I and II anal cancer | RT vs. local excision vs. APR vs. APR after RT | 5-year OS: radiation: 63.7% local excision: 79.6% APR: 28.5% RT + APR: 41.8% p < 0.001 | RT: 79.6% local excision: 92.5% APR: 75.6% RT + APR: 58.8%, p < 0.001 |

| Author | Number of Participants | Anal Cancer Location and Stages Included | Treatments Studied | Treatment Sequence | Relapses | Overall Survival (OS) | Recurrence-Free Survival (RFS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfa-Wali et al. [24] | 15 | Anal verge, T1N0M0 | Local excision only, with a surgical margin of >1 cm | 5-year OS 100% | |||

| Arana et al. [25] | 17 | T1N0M0, superficially invasive or invasive | Local excision: margin of >2 mm for anal canal cancers, >1 cm for anal margin with or without adjuvant EBRT | Local excision, followed by EBRT if margins are inadequate (EBRT performed in 12/17) | 2/17 (11.7%) had local recurrence, salvaged by APR | 5-year OS: 100% | Cancer RFS 5-year: 87% HSIL RFS 5-year: 58.8% |

| MacCabe et al. [37] | 39 | T1-T2N0M0 | Local excision only (margin > 1 mm) | Local excision followed by re-excision vs. adjuvant therapy | R1 excisions: T1 = 15/24 (62.5%), T2 = 12/14 (85.7%) | 5-year OS: 86.2% [95% CI 55.0–96.4] anal canal; 95.7% [95% CI 72.9–99.4] perianal, p = 0.607 | |

| Brogden et al. [38] | 94 | T1-T3N0M0, T1-T2N1M0 | CRT vs. RT only vs. local excision of tumor with other treatment modality vs. APR vs. defunctioning stoma vs. local excision of tumor only | No margin size specified for local excision | 3 (9%) had recurrence in the local excision-only group | No difference in 5-year disease-free survival |

| Author | Number of Participants | Anal Cancer Location and Stages Included | Treatments Studied | Relapses | Results | Overall Survival (OS) | Locoregional Control Rates (LRC) | Colostomy-Free Survival | Inguinal Relapse-Free Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kabarriti et al. [30] | 5927 | nonmetastatic ASCC | HPV-positive vs. HPV-negative disease; differences in radiation dose | No difference in OS for early anal cancer for HPV-negative vs. HPV-positive patients | Entire cohort: 3-year 78.1% 5-year 69.9% 5-year OS for HPV+ 79.3% and HPV− 81.5% | ||||

| Martin et al. [31] | 101 institutions; 45 (44.6%) outpatient radiation oncology centers; 20 (19.8%) university affiliated departments; 36 (35.6%) non-university clinics | Most institutions use IMRT; 94% use 5-FU/mitomycin-based CRT | |||||||

| Zilli et al. (2013) [35] | 116 | T2N0M0 | Elective inguinal node radiation therapy in those treated with RT alone or CRT | 22 patients with recurrence; 7 patients with inguinal relapse | Patients with INRT were more likely to be treated with CRT rather than RT alone | With INRT: 5-year 84.5% +/− 5.8% 5 year without INRT: 77.8% +/− 7% RT only: 71% +/− 7.2% CRT: 85.4% +/− 4.5% | Entire cohort: 79.4% +/− 4.2% For RT group: 74.2% CRT group: 83% | Entire cohort: 5-year 92.3% With INRT: 93.3%+/− 3.2% Without INRT: 90.4% +/− 5.4%, p = 0.733 |

| Certainty Assessment | Certainty * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of Studies | Study Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Considerations | |

| Chemoradiation vs. Radiation | |||||||

| 3 | Non-randomized studies | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | None | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Chemoradiation Alone | |||||||

| 2 | Non-randomized studies | Serious | Very Serious | Serious | Serious | None | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Surgery with Chemoradiation | |||||||

| 2 | Non-randomized studies | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | None | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Surgery Alone | |||||||

| 4 | Non-randomized studies | Serious | Not Serious | Not Serious | Serious | None | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Araradian, C.; Erlick, M.R.; Hunnicutt, E.; Berry-Lawhorn, J.M.; Rivet, E.B.; Duhen, R.; Terlizzi, J.; Cuming, T.; Fang, S.H. A Systematic Review Defining Early Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Identifying Treatment. Cancers 2025, 17, 1646. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101646

Araradian C, Erlick MR, Hunnicutt E, Berry-Lawhorn JM, Rivet EB, Duhen R, Terlizzi J, Cuming T, Fang SH. A Systematic Review Defining Early Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Identifying Treatment. Cancers. 2025; 17(10):1646. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101646

Chicago/Turabian StyleAraradian, Cynthia, Mariah R. Erlick, Emmett Hunnicutt, J. Michael Berry-Lawhorn, Emily B. Rivet, Rebekka Duhen, Joseph Terlizzi, Tamzin Cuming, and Sandy H. Fang. 2025. "A Systematic Review Defining Early Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Identifying Treatment" Cancers 17, no. 10: 1646. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101646

APA StyleAraradian, C., Erlick, M. R., Hunnicutt, E., Berry-Lawhorn, J. M., Rivet, E. B., Duhen, R., Terlizzi, J., Cuming, T., & Fang, S. H. (2025). A Systematic Review Defining Early Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Identifying Treatment. Cancers, 17(10), 1646. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101646