Adjuvant Immunotherapy After Resected Melanoma: Survival Outcomes, Prognostic Factors and Patterns of Relapse

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Outcomes and Asessments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients and Treatment Characteristics

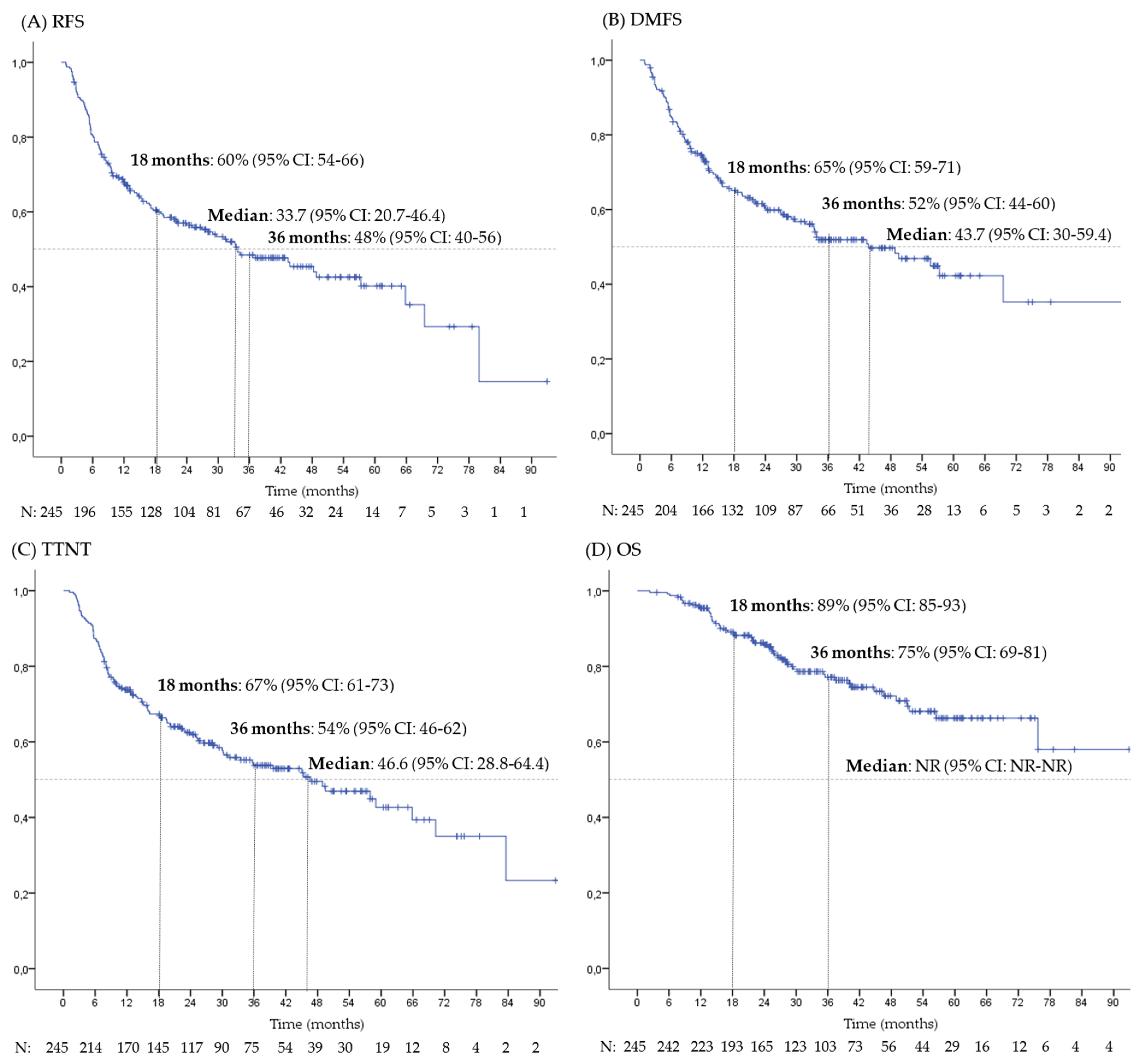

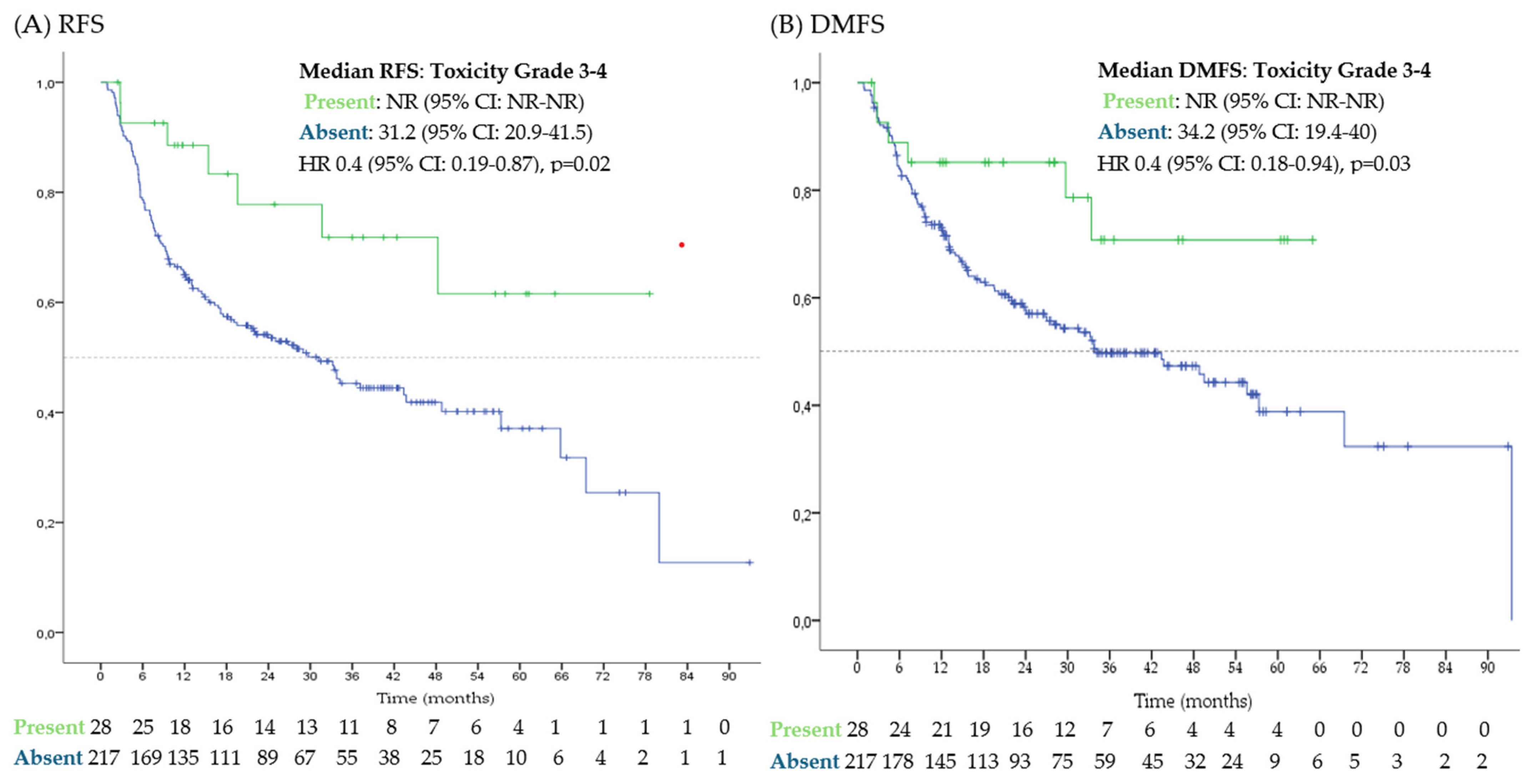

3.2. Survival and Prognostic Factors

3.3. Toxicities

3.4. Patterns of Relapse

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnold, M.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Vaccarella, S.; Meheus, F.; Cust, A.E.; de Vries, E.; Whiteman, D.C.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Cutaneous Melanoma in 2020 and Projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Ribas, A.; Schachter, J.; Arance, A.; Grob, J.J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.M.; Lotem, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-006): Post-hoc 5-year results from an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Grob, J.J.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Karaszewska, B.; Hauschild, A.; Levchenko, E.; Chiarion Sileni, V.; Schachter, J.; Garbe, C.; Bondarenko, I.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes with Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Metastatic Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dummer, R.; Flaherty, K.T.; Robert, C.; Arance, A.; de Groot, J.W.B.; Garbe, C.; Gogas, H.J.; Gutzmer, R.; Krajsová, I.; Liszkay, G.; et al. COLUMBUS 5-Year Update: A Randomized, Open-Label, Phase III Trial of Encorafenib Plus Binimetinib Versus Vemurafenib or Encorafenib in Patients With BRAF V600–Mutant Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 4178–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Rutkowski, P.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Queirolo, P.; Dummer, R.; Butler, M.O.; Hill, A.G.; et al. Final, 10-Year Outcomes with Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 392, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A.M.M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Grob, J.J.; Dummer, R.; Wolchok, J.D.; Schmidt, H.; Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Ascierto, P.A.; Richards, J.M.; et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of stage III melanoma: Long-term follow-up results of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 18071 double-blind phase 3 randomised trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 119, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A.M.M.; Blank, C.U.; Mandala, M.; Long, G.V.; Atkinson, V.; Dalle, S.; Haydon, A.; Lichinitser, M.; Khattak, A.; Carlino, M.S.; et al. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab versus Placebo in Resected Stage III Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A.M.M.; Blank, C.U.; Mandalà, M.; Long, G.V.; Atkinson, V.G.; Dalle, S.; Haydon, A.M.; Meshcheryakov, A.; Khattak, A.; Carlino, M.S.; et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma (EORTC 1325-MG/KEYNOTE-054): Distant metastasis-free survival results from a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A.M.; Kicinski, M.; Blank, C.U.; Mandala, M.; Long, G.V.; Atkinson, V.; Dalle, S.; Haydon, A.; Meshcheryakov, A.; Khattak, A.; et al. Seven-Year Analysis of Adjuvant Pembrolizumab versus Placebo in Stage III Melanoma in the EORTC1325/KEYNOTE-054 Trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 211, 114327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Mandala, M.; Del Vecchio, M.; Gogas, H.J.; Arance, A.M.; Cowey, C.L.; Dalle, S.; Schenker, M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in Resected Stage III or IV Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1824–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascierto, P.A.; Vecchio, M.D.; Mandalá, M.; Gogas, H.; Arance, A.M.; Dalle, S.; Cowey, C.L.; Schenker, M.; Grob, J.-J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage IIIB–C and stage IV melanoma (CheckMate 238): 4-year results from a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1465–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, J.; Del Vecchio, M.; Mandalá, M.; Gogas, H.; Arance Fernandez, A.M.; Dalle, S.; Cowey, C.L.; Schenker, M.; Grob, J.-J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in Resected Stage III/IV Melanoma: 5-Year Efficacy and Biomarker Results from CheckMate 238. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 3352–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke, J.J.; Rutkowski, P.; Queirolo, P.; Vecchio, M.D.; Mackiewicz, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Merino, L.d.l.C.; Khattak, M.A.; Schadendorf, D.; Long, G.V.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 1718–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, J.M.; Del Vecchio, M.; Weber, J.; Hoeller, C.; Grob, J.J.; Mohr, P.; Loquai, C.; Dutriaux, C.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Mackiewicz, J.; et al. Adjuvant nivolumab in resected stage IIB/C melanoma: Primary results from the randomized, phase 3 CheckMate 76K trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2835–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.S.; Schadendorf, D.; Del Vecchio, M.; Larkin, J.; Atkinson, V.; Schenker, M.; Pigozzo, J.; Gogas, H.; Dalle, S.; Meyer, N.; et al. Adjuvant Therapy of Nivolumab Combined With Ipilimumab Versus Nivolumab Alone in Patients With Resected Stage IIIB-D or Stage IV Melanoma (CheckMate 915). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 41, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, E.; Zimmer, L.; Hassel, J.C.; Fluck, M.; Eigentler, T.K.; Loquai, C.; Haferkamp, S.; Gutzmer, R.; Meier, F.; Mohr, P.; et al. Adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus placebo in patients with resected stage IV melanoma with no evidence of disease (IMMUNED): Final results of a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2022, 400, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Hauschild, A.; Santinami, M.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Atkinson, V.; Mandala, M.; Merelli, B.; Sileni, V.C.; Nyakas, M.; Haydon, A.; et al. Final Results for Adjuvant Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Stage III Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichenthal, M.; Mangana, J.; Gavrilova, I.; Lugowska, I.; Shalamanova, G.K.; Kandolf, L.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Mohr, P.; Karanikolova, T.S.; Teterycz, P.; et al. Adjuvant Use of Pembrolizumab for Stage III Melanoma in a Real-World Setting in Europe. Cancers 2024, 16, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, C.N.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Chauhan, D.; Palmieri, D.J.; Lee, B.; Rohaan, M.W.; Mangana, J.; Atkinson, V.; Zaman, F.; Young, A.; et al. Management of early melanoma recurrence despite adjuvant anti-PD-1 antibody therapy☆. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, J.C.; Bhatia, S.; Amin, A.; Pavlick, A.C.; Betts, K.A.; Du, E.X.; Poretta, T.; Shelley, K.; Srinivasan, S.; Sakkal, L.A.; et al. Clinical outcomes of adjuvant nivolumab in resected stage III melanoma: Comparison of CheckMate 238 trial and real-world data. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII 2024, 73, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, H.M.; Tawbi, H.A.; Ascierto, M.L.; Bowden, M.; Callahan, M.K.; Cha, E.; Chen, H.X.; Drake, C.G.; Feltquate, D.M.; Ferris, R.L.; et al. Defining tumor resistance to PD-1 pathway blockade: Recommendations from the first meeting of the SITC Immunotherapy Resistance Taskforce. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Meza, M.M.; Ismail, R.K.; Rauwerdink, D.; van Not, O.J.; van Breeschoten, J.; Blokx, W.A.M.; de Boer, A.; van Dartel, M.; Hilarius, D.L.; Ellebaek, E.; et al. Adjuvant treatment for melanoma in clinical practice—Trial versus reality. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 158, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggermont, A.M.M.; Kicinski, M.; Blank, C.U.; Mandala, M.; Long, G.V.; Atkinson, V.; Dalle, S.; Haydon, A.; Khattak, A.; Carlino, M.S.; et al. Association Between Immune-Related Adverse Events and Recurrence-Free Survival Among Patients With Stage III Melanoma Randomized to Receive Pembrolizumab or Placebo: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients (N: 245) | |

|---|---|

| N (%)/Median [Range] | |

| Sex | |

| - Male | 142 (58%) |

| - Female | 103 (42%) |

| Age (years old) | 59 [19–84] |

| - <65 | 150 (61%) |

| - 139 | 66 (27%) |

| - ≥75 | 29 (12%) |

| Primary site | |

| - Cutaneous melanoma | 202 (82%) |

| - Acral melanoma | 21 (9%) |

| - Mucosal melanoma | 7 (3%) |

| - Unknown primary | 15 (6%) |

| BRAF status | |

| - BRAF wild type | 116 (47%) |

| - BRAF V600 mutation | 108 (44%) |

| - Unknown | 21 (9%) |

| Breslow index (mm) | 3.7 [0–296] |

| - <0.8 | 20 (8%) |

| - 0.8–2 | 32 (13%) |

| - 5 | 44 (18%) |

| - 6 | 31 (13%) |

| - >4 | 103 (42%) |

| - Unknown | 15 (6%) |

| Ulceration | |

| - Absent | 87 (35%) |

| - Present | 136 (56%) |

| - Unknown | 22 (9%) |

| LDH (IU/dL) | 186 [105–545] |

| - <ULN | 111 (45%) |

| - ULN—2xULN | 99 (40%) |

| - 2xULN–5xULN | 29 (12%) |

| - >5xULN | 6 (3%) |

| Mitosis (1/mm2) | |

| - <1 | 31 (13%) |

| - 11 | 118 (48%) |

| - ≥10 | 66 (27%) |

| - Unknown | 30 (12%) |

| Stage (8th AJCC edition) | |

| - IIB | 4 (2%) |

| - IIC | 5 (2%) |

| - IIIA | 15 (6%) |

| - IIIB | 47 (19%) |

| - IIIC | 120 (49%) |

| - IIID | 14 (6%) |

| - IV | 40 (16%) |

| Patients | |

|---|---|

| N (%)/Median [Range] | |

| ICPI Treatment | |

| - Anti-PD-1 monotherapy | 214 (87%) |

| - Nivolumab | 182 (74%) |

| - Pembrolizumab | 23 (9%) |

| - Other | 9(4%) |

| - Anti-PD-1-based combination | 31 (13%) |

| - Ipilimumab–Nivolumab | 15 (6%) |

| - Other combination | 16 (7%) |

| Time on treatment (months) | 11.7 [0.7–13.1] |

| Interval from last surgery initiation of adjuvant treatment | |

| <12 weeks | 192 (78%) |

| >12 weeks | 53 (22%) |

| End of treatment | |

| - Completion | 129 (53%) |

| - Toxicity | 30 (12%) |

| - Relapse | 79 (32%) |

| - Ongoing | 2 (1%) |

| - Unknown | 5 (2%) |

| RFS | Univariate HR | p-Value * | Multivariate HR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| - Male | 37.1 (22.9–51.4) | Reference | ||

| - Female | 26.9–14.2–39.5) | 1.13 (0.79–1.62) | 0.49 | |

| Age (years old) | 0.39 | |||

| - <65 | 33.4 (25.7–41) | Reference | ||

| - 65–74 | 79.9 (79.9-NR) | 0.96 (0.66–1.39) | 0.76 | |

| - ≥75 | 15.4 (0–37.4) | 1.47 (0.9–2.4) | 0.12 | |

| Primary site of melanoma | 0.01 | 2.64 (1.15–6.01) p = 0.02 | ||

| - Cutaneous melanoma | 43.4 (26.1–60.7) | Reference | ||

| - Acral melanoma | 14.5 (6.3–22.6) | 1.72 (0.96–3.08) | 0.07 | |

| - Mucosal melanoma | 9.2 (1.8–16.6) | 3.15 (1.37–7.25) | <0.01 | |

| - Unknown origin | 28 (6.2–49.7) | 1.39 (0.7–2.76) | 0.35 | |

| BRAF status | ||||

| - BRAF wild type | 33.2 (23.18–43.2) | Reference | ||

| - BRAF V600 mutant | 19.1 (3.1–35) | 1.3 (0.9–1.84) | 0.16 | |

| Breslow index (mm) | 0.81 | |||

| - <0.8 | NR (NR-NR) | Reference | ||

| - 0.8–2 | 43.4 (43.4-NR) | 1.01 (0.91–2.15) | 0.81 | |

| - 5 | 33.8 (16.6–51) | 1.25 (0.66–2.39) | 0.5 | |

| - 6 | 24 (0-NR) | 1.32 (0.65–2.68) | 0.44 | |

| - >4 | 37.1 (15.4–58.9) | 1.08 (0.6–1.93) | 0.8 | |

| Ulceration | ||||

| - Absent | 57.3 (32.7–81.9) | Reference | ||

| - Present | 31.2 (19.9–42.5) | 1.29 (0.87–1.92) | 0.21 | |

| LDH | 0.47 | |||

| - <ULN | 43.7 (26.6–60.8) | Reference | ||

| - ULN—2xULN | 19.5 (11.5–27.5) | 1.37 (0.94–2) | 0.11 | |

| - 2xULN–5xULN | 79.9 (49.2–110.7) | 0.53 (0.27–1.06) | 0.07 | |

| - >5xULN | 29.7 (16.1–43.3) | 1.15 (0.79–1.66) | 0.46 | |

| Mitosis (/mm2) | 0.96 | |||

| - <1 | 48.8 (48.7-NR) | Reference | ||

| - 11 | 37.1 (14.8–59.5) | 0.93 (0.52–1.64) | 0.79 | |

| - ≥10 | 33.8(19.1–48.4) | 0.95 (0.51–1.77) | 0.87 | |

| Stage (8th AJCC edition) | 1.5 (1.01–2.37) | 0.04 | 1.5 (0.98–2.33) p = 0.06 | |

| - IIB-IIC | NR (NR-NR) | Reference | ||

| - IIIA-IIIB | 48.3 (29.8–66.7) | |||

| - IIIA | 43.4 (6.2–80.6) | 2.66 (0.32–22.14) | 0.37 | |

| - IIIB | 48.3 (24.7–71.8) | 4.89 (0.65–36.51) | 0.12 | |

| - IIIC-IIIID | 23.9 (11.7–36.2) | |||

| - IIIC | 24 (11.2–36.7) | 7.06 (0.98–50.86) | 0.05 | |

| - IIID | 19.1 (5.7–42.7) | 7.01 (0.88–55.57) | 0.06 | |

| - IV | 31.7 (20.6–42.7) | 6.74 (0.91–49.77) | 0.06 | |

| Interval from last resection to initiation of adjuvant treatment | ||||

| <12 weeks | 43.7 (31.5–55.9) | Reference | 1.68 (1.13–2.5) p = 0.01 | |

| >12 weeks | 14.7 (8.1–21.3) | 1.64 (1.11–2.44) | 0.01 |

| Any Grade | Grade 3–4 | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| - No toxicity | 135 (55%) | 218 (89%) |

| - Any toxicity | 110 (45%) | 27 (11%) |

| Toxicity * | ||

| - Cutaneous toxicity | 76 (31%) | 1 (<1%) |

| - Hypothyroidism | 12 (5%) | 0 |

| - Colitis | 10 (4%) | 4 (2%) |

| - Arthritis | 9 (4%) | 1 (<1%) |

| - Hepatic toxicity | 8 (3%) | 7 (3%) |

| - Pneumonitis | 8 (3%) | 2 (1%) |

| - Nephritis | 4 (2%) | 3 (1%) |

| - Hypophysitis | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| - Pancreatic toxicity | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| - Adrenal insufficiency | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| - Gastritis | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| - Myositis | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| - Myocarditis | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| - Myelitis | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| All Patients with Relapse | Primary Resistance/Early Relapse | Late Relapse | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| N = 123 | N = 78 | N = 45 | |

| Location of relapse | |||

| - Locoregional relapse | 29 (24%) | 18 (23%) | 11 (24%) |

| - Systemic relapse only | 70 (57%) | 40 (51%) | 30 (66%) |

| - Locoregional and systemic | 24 (19%) | 20 (26%) | 4 (9%) |

| Systemic relapse: affected organs * | |||

| - Distant lymph nodes | 74 (60%) | 49 (63%) | 25 (55%) |

| - Soft tissues | 46 (37%) | 34 (43%) | 12 (26%) |

| - Bone | 21 (17%) | 12 (15%) | 9 (20%) |

| - Lung and pleura | 35 (28%) | 20 (26%) | 15 (33%) |

| - Liver | 14 (11%) | 12 (15%) | 2 (4%) |

| - Brain | 18 (15%) | 7 (9%) | 11 (24%) |

| - Others ** | 10 (8%) | 8 (10%) | 2 (4%) |

| Stage at recurrence | |||

| - M0 | 29 (24%) | 15 (19%) | 11 (24%) |

| - M1a | 50 (41%) | 39 (50%) | 14 (31%) |

| - M1b | 12 (10%) | 4 (5%) | 8 (18%) |

| - M1c | 16 (13%) | 13 (17%) | 3 (7%) |

| - M1d | 16 (13%) | 7 (9%) | 9 (20%) |

| Number of metastatic sites | |||

| - Less than 3 | 104 (85%) | 64 (82%) | 40 (89%) |

| - 3 or more | 19 (15%) | 14 (18%) | 5 (11%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinez-Recio, S.; Molina-Pérez, M.A.; Muñoz-Couselo, E.; Sevillano-Tripero, A.R.; Aya, F.; Arance, A.; Orrillo, M.; Martin-Liberal, J.; Fernandez-Morales, L.; Lesta, R.; et al. Adjuvant Immunotherapy After Resected Melanoma: Survival Outcomes, Prognostic Factors and Patterns of Relapse. Cancers 2025, 17, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17010143

Martinez-Recio S, Molina-Pérez MA, Muñoz-Couselo E, Sevillano-Tripero AR, Aya F, Arance A, Orrillo M, Martin-Liberal J, Fernandez-Morales L, Lesta R, et al. Adjuvant Immunotherapy After Resected Melanoma: Survival Outcomes, Prognostic Factors and Patterns of Relapse. Cancers. 2025; 17(1):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17010143

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez-Recio, Sergio, Maria Alejandra Molina-Pérez, Eva Muñoz-Couselo, Alberto R. Sevillano-Tripero, Francisco Aya, Ana Arance, Mayra Orrillo, Juan Martin-Liberal, Luis Fernandez-Morales, Rocio Lesta, and et al. 2025. "Adjuvant Immunotherapy After Resected Melanoma: Survival Outcomes, Prognostic Factors and Patterns of Relapse" Cancers 17, no. 1: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17010143

APA StyleMartinez-Recio, S., Molina-Pérez, M. A., Muñoz-Couselo, E., Sevillano-Tripero, A. R., Aya, F., Arance, A., Orrillo, M., Martin-Liberal, J., Fernandez-Morales, L., Lesta, R., Quindós-Varela, M., Nieva, M., Vidal, J., Martinez-Perez, D., Barba, A., & Majem, M. (2025). Adjuvant Immunotherapy After Resected Melanoma: Survival Outcomes, Prognostic Factors and Patterns of Relapse. Cancers, 17(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17010143