Simple Summary

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death due to gynecologic malignancies. Peritoneal metastases represent the most common pathway for the spread of OC, both at the time of initial diagnosis and at recurrence. Accurate mapping of peritoneal metastases helps in planning the appropriate therapeutic strategy, predicting the likelihood of optimal cytoreduction, and identifying potentially unresectable or difficult disease sites that may require surgical technique modifications. Preoperative diagnostic work-up with multidetector CT (MDCT), MRI, including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), or FDG PET/CT plays a vital role in the accurate assessment of the extent of peritoneal carcinomatosis. In this article, the aim was to update the role of MDCT, MRI, including DWI, and FDG PET/CT in the detection of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature.

Abstract

This review aims to compare the diagnostic performance of multidetector CT (MDCT), MRI, including diffusion-weighted imaging, and FDG PET/CT in the detection of peritoneal metastases (PMs) in ovarian cancer (OC). A comprehensive search was performed for articles published from 2000 to February 2023. The inclusion criteria were the following: diagnosis/suspicion of PMs in patients with ovarian/fallopian/primary peritoneal cancer; initial staging or suspicion of recurrence; MDCT, MRI and/or FDG PET/CT performed for the detection of PMs; population of at least 10 patients; surgical results, histopathologic analysis, and/or radiologic follow-up, used as reference standard; and per-patient and per-region data and data for calculating sensitivity and specificity reported. In total, 33 studies were assessed, including 487 women with OC and PMs. On a per-patient basis, MRI (p = 0.03) and FDG PET/CT (p < 0.01) had higher sensitivity compared to MDCT. MRI and PET/CT had comparable sensitivities (p = 0.84). On a per-lesion analysis, no differences in sensitivity estimates were noted between MDCT and MRI (p = 0.25), MDCT and FDG PET/CT (p = 0.68), and MRI and FDG PET/CT (p = 0.35). Based on our results, FDG PET/CT and MRI are the preferred imaging modalities for the detection of PMs in OC. However, the value of FDG PET/CT and MRI compared to MDCT needs to be determined. Future research to address the limitations of the existing studies and the need for standardization and to explore the cost-effectiveness of the three imaging modalities is required.

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) represents the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer among women, the fifth cause of cancer death, and the commonest cause of death due to gynecologic malignancies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. An estimated number of 19,680 new cases of OC are expected to be diagnosed in the US and 12,740 women are expected to die from the disease in 2024 [2]. Most cases (90%) are epithelial ovarian carcinomas and the majority are high-grade serous carcinomas. The most important revision in the last FIGO staging classification is that ovarian, fallopian, and primary peritoneal cancers are considered as one entity [9].

Ovarian cancer has a poor prognosis, with a 5-year relative survival rate of 48%, mainly because most women are diagnosed with advanced-stage disease [2]. Moreover, the percentage of recurrence in OC is very high. The standard of care in OC includes either primary debulking surgery (PDS) followed by adjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) prior to interval debulking surgery (IDS) and postoperative chemotherapy [10,11,12].

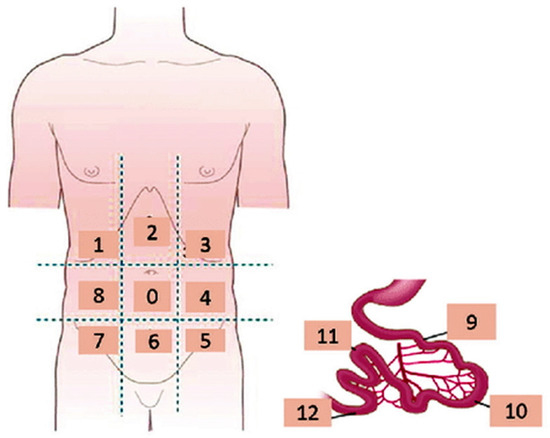

Peritoneal metastases (PMs) represent the commonest pathway for the spread of OC and are often seen either at the time of initial diagnosis or at recurrence [3,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The peritoneal cancer index (PCI) introduced by Jacquet and Sugarbaker combined the distribution of PMs in 13 abdominopelvic regions (ARs) with the tumor size providing a measurement of the volume of peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) and also a valuable prognostic index (Table 1, Figure 1) [23].

Table 1.

The Sugarbaker Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Index (ARs: abdominopelvic regions; PCI: peritoneal carcinomatosis index) [23].

Figure 1.

Coronal schematic drawing showing the Sugarbaker peritoneal carcinomatosis index.

Imaging has a fundamental role in the accurate diagnosis of PMs in OC, helping to plan the appropriate therapeutic strategy, predict the likelihood of optimal cytoreduction, and identify potentially unresectable or difficult disease sites, which may require either IDS following chemotherapy or surgical technique modifications during PDS [3,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

Multidetector CT (MDCT) is considered the examination of choice for the initial staging of OC and for the evaluation of the extent of the disease in suspected recurrence [1]. However, CT has limitations, mainly low soft-tissue resolution, and difficulty in depicting small peritoneal implants or implants at certain anatomic areas, including the root of mesentery, lesser omentum, and serosal surfaces of the small bowel, especially in the absence of ascites [1,3,18,21,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

MRI represents another reliable imaging tool for the assessment of PC. The efficacy of the technique in the detection of PMs has been improved by using fat-suppressed delayed contrast-enhanced imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) [16,21,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Specifically, DWI improves the detection of small peritoneal hypercellular implants, even in the absence of ascites, due to their high signal against the hypointense background of normal tissues. However, MRI is recommended in specific circumstances, such as women with borderline ovarian tumors or OCs that have been previously staged with fertility preservation and also in cases with inconclusive CT findings [1].

The hypermetabolic activity of PMs increases their conspicuity using FDG PET/CT. CT and FDG PET/CT are considered equivalent alternatives for the detection of recurrent OC [1,17,30,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Based on the results of a recently published meta-analysis, FDG PET/CT had high diagnostic accuracy, with 88% sensitivity and 89% specificity in the detection of recurrent OC [45]. Up to now, FDG PET or FDG PET/CT may be used as an adjunct tool in the initial staging of OC, in cases of indeterminate CT findings [1].

Systematic reviews on the role of cross-sectional imaging in the detection of PC in women with OC are lacking. A few recently published meta-analyses assessed the diagnostic accuracy of imaging modalities in the detection of PMs from various primary malignancies, including OC [46,47,48].

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to compare the diagnostic performance of MDCT, MRI, including DWI, and FDG PET/CT in the detection of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [49]. The systematic review has not been registered.

2.1. Search Strategy

A systematic and comprehensive literature search was performed for all publications that reported the diagnostic performance of MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT in the detection of PMs in OC. Data extraction was independently performed by two researchers (ACT and MT) from the PubMed/MEDLINE database and included articles published from 2000 to February 2023.

The following keywords were used: “ovarian cancer” OR “peritoneal metastases” OR “peritoneal carcinomatosis” OR “multidetector CT” OR “MDCT” OR “magnetic resonance imaging” OR “MRI” OR “diffusion-weighted imaging” OR “DWI” OR “fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT)” and “FDG PET/CT”.

Articles found to be suitable on the basis of their title and abstract were subsequently selected to further determine appropriateness for inclusion in this meta-analysis. Only papers in the English language were assessed. Full-text studies were further evaluated, and exclusion criteria were applied to identify final papers for inclusion. References were manually screened to identify additional studies.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis/suspicion of PMs in patients with ovarian/fallopian/primary peritoneal cancer; initial staging or suspicion of recurrence (primary outcome); MDCT, MRI, and/or FDG PET/CT performed for the detection of PMs; population of at least 10 patients; surgical results, histopathologic analysis, and/or radiologic follow-up, used as a reference standard; per-patient and per-region data included; and data for calculating sensitivity and specificity reported. Discrepancies regarding potential eligibility and inclusion were resolved by consensus.

Studies were excluded if results for different imaging modalities were presented in combination and if data on the performance of each individual technique were unavailable. Studies including patients with the diagnosis of PMs from tumors other than OC were considered eligible only if it was possible to extrapolate results obtained on PC from OC.

2.3. Data Extraction

From each study, the following design characteristics were recorded: first author and year of publication; study design (prospective or retrospective); primary outcome; characteristics of study population, including number of patients with ovarian/fallopian/primary peritoneal cancer, age, number of patients with PMs, number and size of PMs, location of PMs; imaging modality, including MDCT, MRI or FDG PET/CT; report of reference test; time interval between imaging modalities; and time interval between imaging and reference standard.

Imaging characteristics included detailed information on the following: imaging equipment (type of scanner for MDCT and FDG PET/CT, magnetic field strength); imaging technique (phases and reformations for MDCT, type of coil, sequences, section thickness, and b-values for MRI); bowel preparation (laxatives and spasmolytic drugs), and use of luminal and/or intravenous contrast medium.

The numbers of true-positive (TP), false-negative (FN), false-positive (FP), and true-negative (TN) results for the detection of PMs were extracted on a per-patient and per-region basis. When cumulative data on the detection of PMs were not reported, the results from the abdominopelvic region with the best diagnostic performance were included in the analysis.

Regarding the per-patient analysis, the diagnostic odds ratios (DORs) were also estimated. A bivariate random effect meta-analytic method was used to estimate pooled sensitivity, specificity, and summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curves. Via the percentage of heterogeneity between the studies, computing I2 values were calculated. I2 values equal to 25%, 50%, and 75% were assumed to represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Study heterogeneity was also assessed visually via funnel plots.

When at least three datasets were available for the three imaging modalities, subgroup analyses were performed for the different ARs, including AR0 (central abdomen), AR1 (right hypochondrium), AR2 (epigastrium), AR3 (left hypochondrium), AR4 (left lumbar region), AR5–7 and AR6 (pelvis), AR8 (right lumbar region), small bowel (AR9–12), colon and mesentery (Table 1, Figure 1), on a per-patient and a per-region basis [23].

2.4. Quality Assessment

Analyses were performed using the RevMan software (ReviewManager, version 5.3; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). To assess the methodological quality of the included primary studies and to detect potential bias, we used the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool [50].

3. Results

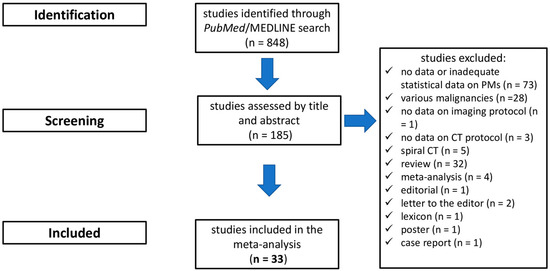

The initial search in the electronic database resulted in 848 articles. Following a review of the titles and abstracts, 187 studies were selected as potentially relevant, and their references were cross-checked. Thirty-three publications eventually fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were selected for quantitative synthesis (Table 2) [26,27,30,42,44,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. The flow chart of the selection process is shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the eligible studies (OC: ovarian cancer; PMs: peritoneal metastases, ARs: abdominopelvic regions; n/a: non-applicable).

Figure 2.

Flowchart depicting study selection.

A total of 2025 women with OC were included in the meta-analysis, with a mean age of 57.4 years (range, 19–91 years). The primary outcome included 19 studies with initial diagnosis of ovarian/fallopian/peritoneal cancer, 7 reports with recurrent cancer, and 7 studies with primary or recurrent OC. Advanced OC (FIGO stages III and IV) was reported in 1453 patients (Table 2). The presence of PMs was reported in 487 women and included 4.588 ARs (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Location of PMs (ARs: abdominopelvic regions; n/a: non-applicable).

3.1. Study Characteristics

The studies selected for meta-analysis included 15 prospective and 18 retrospective articles (Table 2). In total, 23 datasets evaluated the presence of PMs in OC with MDCT [26,27,30,52,56,57,58,59,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,78] (Table 4); 2, 3, and 8 studies were performed on a 4-row [52,58], 16-row [56,57,74], and 64-row [27,30,59,63,67,70,72,75] MDCT scanner, respectively, 4 studies used both a 16-row and a 64-row CT [64,66,73,76], and 1 report used a 4-row, a 16-row, and a 64-row [65] CT machine (Table 5). Overall, 20 studies [27,30,52,56,57,58,59,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,78] reported the intravenous administration of iodinated contrast medium; 10 of them used the portal phase [27,56,57,58,59,66,67,68,73,78], 4 used both the arterial and the portal phase [52,65,74,76], 1 used the arterial phase [72], and 1 study used both the portal and the delayed phase [69]. The use of luminal contrast was reported in 15 studies [30,52,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,78]; 8 studies reported the oral administration of H2O and diluted contrast medium, including iodinated contrast material in 4 reports [30,66,74,78], gastrografin in 2 studies [69,72], mannitol in 1 study [70], Macrogol in 1 report [65], and 2 studies used H2O, administered orally in 1 report [52] and as a rectal enema in 1 study [67]. Multiplanar reformations (MPRs) used for data interpretation were reported in 11 studies [27,52,56,57,59,65,67,69,70,73,78]; the application of coronal and sagittal reformations was reported in 4 studies [27,56,57,78]; coronal, sagittal, and oblique MPRs were used in 2 studies [52,65]; coronal plane in 2 reports [59,73]; and in 1 report [70] combined MPRs with three-dimensional maximum intensity projection reformations were performed (Table 5).

Table 4.

Characteristics of imaging modalities (MDCT: multidetector CT; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; 18F FDG-PET/CT: fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT, PDS: primary debulking surgery; SLL: second-look laparotomy; IDS: interval debulking surgery; EL: exploratory laparotomy; CECT: contrast-enhanced CT, WB-MRI: whole-body MRI; n/a: non-applicable).

Table 5.

Description of MDCT features (n/a: non-applicable; cm: contrast medium; mgI/mL: iodine content; kV: kilovolt; MIP: maximum-intensity projection; CECT: contrast-enhanced CT).

MRI was used in 10 studies [30,51,53,55,61,62,66,67,73,78], 5 performed on a 1.5 T [30,51,53,55,61] and 5 on a 3.0 T system [62,66,67,73,78] (Table 4 and Table 6). DWI was applied in six studies [30,62,66,67,73,78], including three reports with whole-body DWI (WB-DWI) [66,73,78] (Table 6). Gadolinium chelate was administered intravenously in nine studies [51,53,55,61,62,66,67,73,78]; two studies reported the use of the portal phase [66,67] and one study used three post-contrast phases (arterial, portal, and delayed) [61]. The administration of luminal contrast prior to the MRI was reported in four studies [66,67,73,78]; two of them reported the use of pineapple juice [66,73], one study used both H2O and pineapple juice [78], and, in one study, H2O was given via the rectum [67]. Bowel preparation with intravenous or intramuscular administration of spasmolytic agents was reported in eight studies [30,51,53,55,66,67,73,78] (Table 6).

Table 6.

Description of MRI features (T: Tesla; cm: contrast medium; WB-DWI: whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging; im: intramuscularly; iv: intravenously; n/a: non-applicable; DCE: dynamic contrast-enhanced).

FDG PET/CT was used in 16 studies [30,42,44,54,55,56,57,60,61,63,64,66,67,68,70,77], including 7 reports with diagnostic contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) [30,56,57,63,66,70,77] (Table 4 and Table 7). Six studies were performed on a 16-row [42,56,57,64,67,68] scanner, four on a 64-row [30,63,70,77] system, and three studies, each one used a 4-row [54], an 8-row [55], and a spiral [66] CT machine (Table 7).

Table 7.

Description of FDG PET/CT features (n/a: non-applicable; cm; contrast medium; mgI/mL: iodine content; kV: kilovolt).

The following reference tests were used: surgical and histopathologic results (n = 21) [26,30,42,44,51,53,54,57,60,62,63,64,65,67,71,72,74,75,76,77,78], surgical findings (n = 3) [52,58,68], surgical and histopathologic results or follow-up (n = 8) [27,55,56,59,61,66,70,73], and follow-up (n = 1) [69] (Table 4).

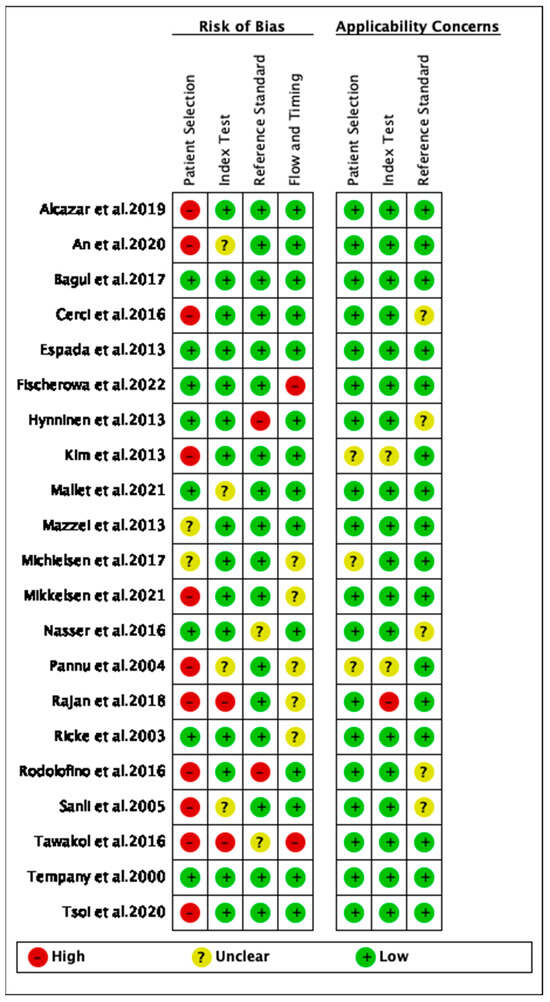

3.2. Quality Assessment

Study quality grading using QUADAS II scores showed that in terms of risk bias and regarding patient selection, index test, reference standard, flow, and timing, the majority of studies included in the analysis were of high to good quality (Figure 3). In terms of applicability, the quality of reporting on patient selection, index test, and the gold standard was good (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The quality assessment of the included studies [26,27,44,50,51,52,53,61,62,63,64,65,66,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,77,78].

3.3. Diagnostic Performance

3.3.1. Per-Patient Analysis

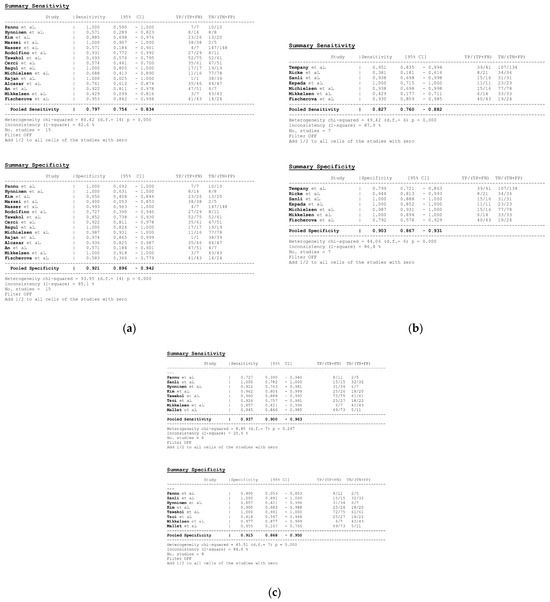

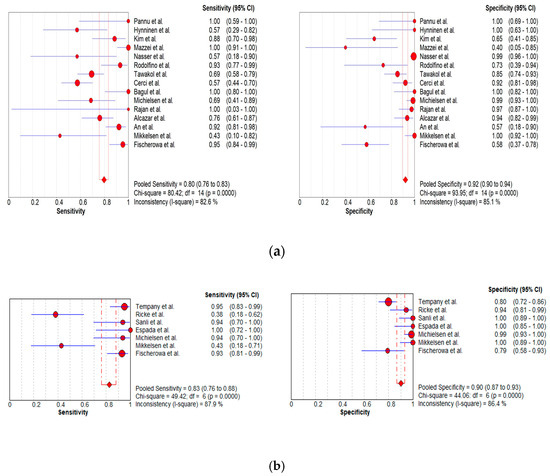

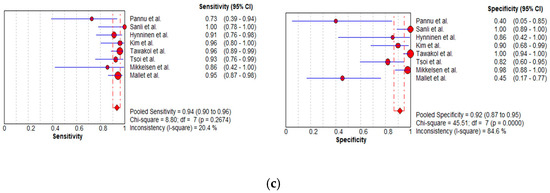

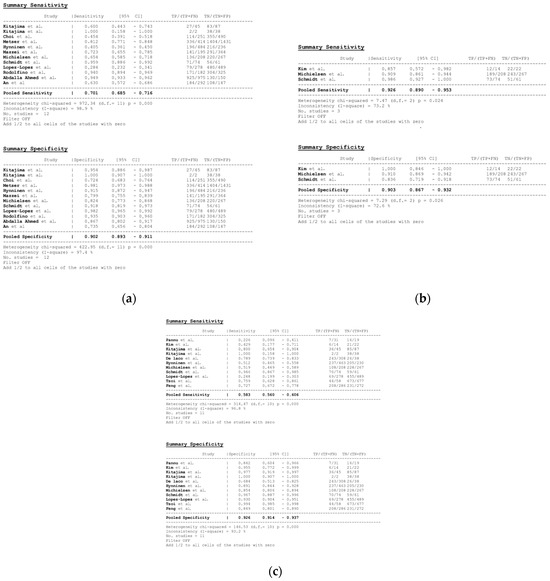

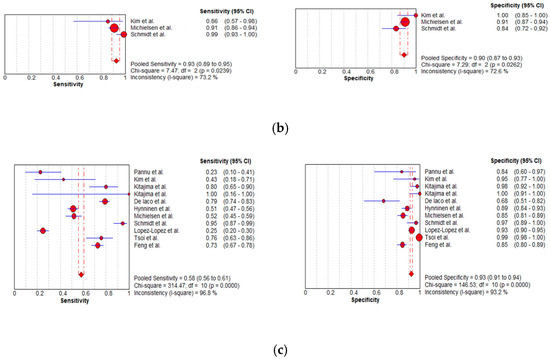

In total, 15, 7, and 8 datasets for MDCT [26,27,30,52,63,64,65,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,78], MRI, including DWI [30,51,53,61,62,73,78], and FDG PET/CT [30,44,54,61,63,64,70,77], respectively, were included in the per-patient analysis. The sensitivity estimates for MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT on a per-patient basis were 79.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 75.6–83.4%, I2 = 82.6%), 82.7% (95% CI, 76.0–88.2%, I2 = 87.9%), and 93.7% (95% CI, 90.0–96.3%, I2 = 20.4%), respectively. The specificity estimates for MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT on a per-patient basis were 92.1% (95% CI, 89.6–94.2%, I2 = 85.1%), 90.3% (95% CI, 86.7–93.1%, I2 = 86.4%), and 91.5% (95% CI, 86.8–95.0%, I2 = 84.6%), respectively (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Figure 6 shows study heterogeneity via funnel plots.

Figure 4.

Forest plots for the pooled sensitivity and specificity calculation for (a) MDCT [26,27,30,52,63,64,65,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,78], (b) MRI [30,51,53,61,62,73,78], and (c) FDG PET/CT [30,44,54,61,63,64,70,77] in the detection of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer, on a per-patient basis (CI: confidence interval; TP: true positive; FN: false negative; TN: true negative).

Figure 5.

Foster plots for sensitivity and specificity for (a) MDCT [26,27,30,52,63,64,65,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,78], (b) MRI [30,44,54,61,63,64,70,77], and (c) FDG PET/CT [30,51,53,61,62,73,78] in the detection of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer, on a per-patient basis (CI: confidence interval).

Figure 6.

Funnel plots of the (a) MDCT, (b) MRI, and (c) FDG PET/CT data on a per-patient basis.

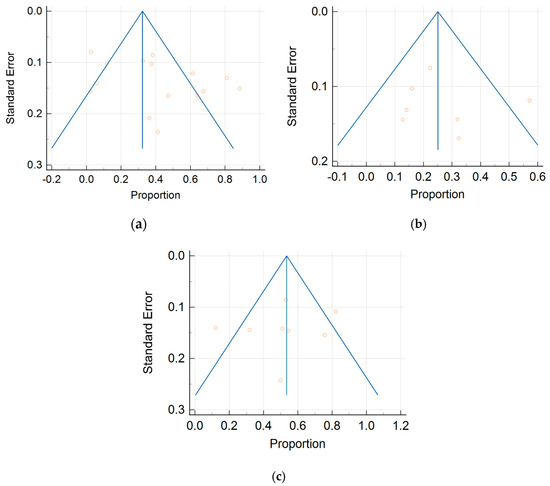

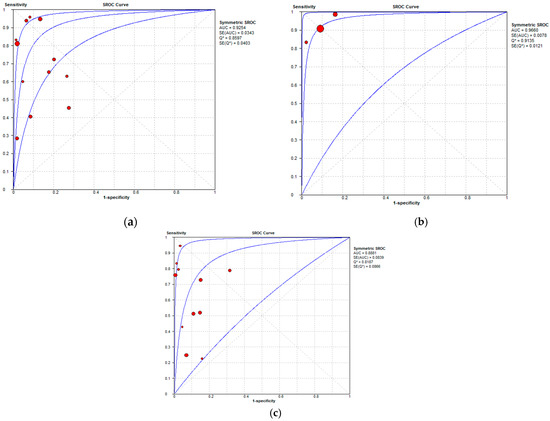

The per-patient diagnostic performance, including TP, FN, FP, and TN findings; sensitivity; specificity; positive predictive value (PPV); and negative predictive value (NPV) for each imaging modality are presented in Tables S1–S3. The DOR estimates for MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT on a per-patient basis were 29.55% (95% CI, 17.54–49.78%), 93.95% (95%CI, 27.41–321.97%), and 84.15% (95%CI, 17.62–401.8%), respectively. The summary area-under-the-curve (SAUC) for MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT was determined to be 0.91, 0.96, and 0.97, respectively (Figure 7). The sensitivity estimates for MRI (p = 0.03) and FDG PET/CT (p < 0.01) were higher than that for MDCT, on a per-patient basis. FDG PET/CT had higher sensitivity compared to MRI, although non-significant (p = 0.84).

Figure 7.

Summary receiver operating characteristic curves depicting the diagnostic performance of (a) MDCT, (b) MRI, and (c) FDG PET/CT in the detection of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer, on a per-patient basis.

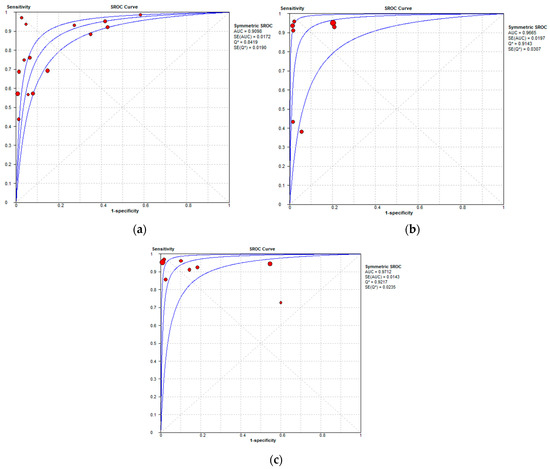

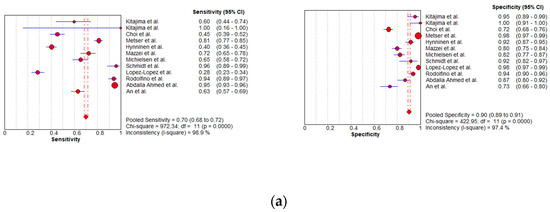

3.3.2. Per-Region Analysis

Per-region data were analyzed for 338 women with advanced OC and 3.881 ARs (Tables S4–S6). Overall, 12, 3 and 11 datasets for MDCT [27,56,57,58,59,63,65,66,67,68,69,76], MRI, including DWI [55,66,67], and FDG PET/CT [42,54,55,56,57,60,63,66,67,68,77], respectively, were included in the per-region analysis. On a per-region basis, comparison between MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT for detecting PMs revealed a sensitivity of 70.1% (95% CI, 68.5–71.6% I2 = 98.9%), 92.6% (95% CI, 89.0–95.3%, I2 = 73.2%), and 58.3% (95% CI, 56–60.6%, I2 = 96.8%), respectively. The specificity estimates for MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT were 90.2% (95% CI, 89.3–91.1%, I2 = 97.4%), 90.3% (95% CI, 86.7–93.2%, I2 = 72.6%), and 92.6% (95% CI, 91.4–93.7%, I2 = 92.6%), respectively (Figure 8 and Figure 9). The per-region diagnostic performances are presented in Tables S4–S6. MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT had an AUC of 0.92, 0.96, and 0.89, respectively, on a per-region analysis (Figure 10). No differences in sensitivity estimates were found between MDCT and MRI (p = 0.25), MDCT and FDG PET/CT (p = 0.68), and MRI and FDG PET/CT (p = 0.35), on a per-region basis.

Figure 8.

Forest plots for the pooled sensitivity and specificity calculation for (a) MDCT [27,56,57,58,59,63,65,66,67,68,69,76], (b) MRI [55,66,67], and (c) FDG PET/CT [42,54,55,56,57,60,63,66,67,68,77] in the detection of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer, on a per-region basis (CI: confidence interval; TP: true positive; FN: false negative; TN: true negative).

Figure 9.

Foster plots for sensitivity and specificity for (a) MDCT [27,56,57,58,59,63,65,66,67,68,69,76], (b) MRI [55,66,67], and (c) FDG PET/CT [42,54,55,56,57,60,63,66,67,68,77] in the detection of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer, on a per-region basis (CI: confidence interval).

Figure 10.

Summary receiver operating characteristic curves depicting the diagnostic performance of (a) MDCT, (b) MRI, and (c) FDG PET/CT in the detection of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer, on a per-region basis.

3.3.3. Subgroup Analysis: Abdominopelvic Regions

Per-Patient Analysis

Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10 show sensitivity and specificity estimates for the three imaging modalities in different ARs, on a per-patient basis.

Table 8.

Diagnostic accuracy of MDCT in different abdominopelvic regions on a per-patient basis (AR: abdominopelvic region; CI: confidence interval; AUC: area under the curve).

Table 9.

Diagnostic accuracy of MRI in different abdominopelvic regions on a per-patient basis (AR: abdominopelvic region; CI: confidence interval; AUC: area under the curve).

Table 10.

Diagnostic accuracy of FDG PET-CT in different abdominopelvic regions on a per-patient basis (AR: abdominopelvic region; CI: confidence interval; AUC: area under the curve).

Datasets for assessing per-patient diagnostic accuracy of MDCT were available for all ARs, including AR0 [52,63,71,72,74,75,78], AR1 [26,30,52,63,72,74,75,78], AR2 [52,72,74,78], AR3 [26,52,63,72,74,75,78], AR4 [72,74,78], AR5–7 [26,52,63,71,72,74,75,78], AR6 [26,52,71,72,74,75,78], AR8 [72,74,78], diaphragm [26,52,63,71,72,78], small bowel [26,63,65,72,74,75,78], colon [26,63,72,78], and mesentery [26,30,52,63,71,72,73,75,78] (Table S7). The accuracy of MDCT in the detection of PMs on a per-patient basis was higher in six ARs: the left hypochondrium (AR3), including the undersurface of the left hemidiaphragm, spleen, pancreatic tail of the pancreas, and anterior and posterior surfaces of the stomach, with sensitivity estimates of 61.8% (95% CI, 50.9–71.9%), specificity estimates 97.9% (95% CI, 95.8–99.2%), and an AUC of 0.93; the diaphragm, with a sensitivity of 49.7% (95% CI, 42.6–56.9%), a specificity of 97.7% (95% CI, 94.8–99.3%), and an AUC of 0.91; the pelvis–hypogastrium (AR6), including the female internal genitalia, the urinary bladder, the cul-de-sac of Douglas, and the rectosigmoid colon, with a sensitivity of 66.2% (95% CI, 59.7–72.3%), a specificity of 93.3% (95% CI, 89.7–95.9%), and an AUC of 0.92; and the central abdomen (AR0), including the midline abdominal incision, the greater omentum, and the transverse colon, with sensitivity estimates of 80.1% (95% CI, 74.5–84.9%), specificity estimates 89% (95% CI, 83.1–93.3%), and an AUC of 0.91; left lumbar region (AR4), including the descending colon and the left paracolic gutter, with sensitivity estimates of 73% (95% CI, 60.3–83.4%), specificity estimates 86.3% (95% CI, 76.7–92.9%), and an AUC of 0.92; and pelvis (A5–7), with a sensitivity of 64.1% (95% CI, 58.4–69.4%), a specificity of 95.1% (95% CI, 91.6–97.4%), and an AUC of 0.90 (Table 8). MDCT had the lowest diagnostic performance on a per-patient basis in two regions: the colon, with a sensitivity of 30.5% (95% CI, 23.2–38.5%), a specificity of 95.8% (95% CI, 92.2–98.1%), and an AUC of 0.36, and the mesentery, with a sensitivity of 33.8% (95% CI, 27.2–41%), a specificity of 96.9% (95% CI, 94.9–98.3%), and an AUC of 0.66 (Table 8).

Datasets for assessing the per-patient diagnostic accuracy of MRI were available for only three ARs, including, AR0 [51,53,78], the diaphragm [51,53,62,78], and the mesentery [30,51,62,73,78] (Table S8). The sensitivity (59.2%) and specificity (75.7%) of MRI were higher in the mesentery, with an AUC of 0.90 (Table 9).

Available data for assessing the diagnostic performance of FDG PET/CT on a per-patient basis included five ARs: AR0 [44,63,77], AR1 [30,44,63,77], AR3 [44,63,77], A5–7 [44,63,77], and mesentery [30,63,77] (Table S9). Detection rates for FDG PET/CT were higher in two regions: the central abdomen (AR0), with sensitivity estimates of 92.9% (95% CI, 86.5–96.9%), specificity estimates of 85.2% (95% CI, 73.8–93%), and an AUC of 0.95, and the pelvis (AR5–7), with sensitivity estimates of 91.5% (95% CI, 85–95.9%), specificity estimates of 87.5% (95% CI, 74.8–95.3%), and an AUC of 0.94 (Table 10).

Per-Region Analysis

On a per-region analysis, data assessing the diagnostic accuracy were available for MDCT in four regions, including AR0, AR5–7, and AR6, the diaphragm and mesentery [27,57,58,66], and for FDG PET/CT in six regions, including AR0 [42,57,60,66], AR1 [42,54,60,66], AR3 [42,54,60,66], AR4 [42,60,66], AR8 [42,60,66], and the pelvis (AR5–7) [42,54,57,60,66] (Tables S10 and S11). The assessment of MRI data in different ARs on a per-region basis was not possible due to the small number of studies.

The highest detection rates for MDCT on a per-region analysis were noted at the pelvis–hypogastrium [sensitivity, 24.4% (95% CI, 12.4–40.3%); specificity, 96.4% (95% CI, 89.9–99.3%); and, AUC, 0.99] and the lowest detection rates were found at the mesentery [sensitivity: 43.4% (95% CI, 29.8–57.7%); specificity, 90.7% (95% CI, 83.6–95.5%); and, AUC: 0.68] (Table 11). The sensitivity for detecting PMs in different ARs for FDG PET/CT on a per-region basis revealed better results in the right hypochondrium [sensitivity: 66.7% (95% CI, 54.8–77.1%); specificity, 81.8% (95% CI, 69.1–90.9%); and, AUC: 0.99] (Table 12).

Table 11.

Diagnostic accuracy of MDCT in different abdominopelvic regions on a per-region basis (AR: abdominopelvic region; CI: confidence interval; AUC: area under the curve).

Table 12.

Diagnostic accuracy of FDG PET-CT in different abdominopelvic regions on a per-region basis (AR: abdominopelvic region; CI: confidence interval; AUC: area under the curve).

4. Discussion

According to our knowledge, this is an up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis that exclusively compares the diagnostic performance of MDCT, MRI, including DWI, and FDG PET/CT in the detection of peritoneal metastases in women with ovarian cancer. In total, 33 studies, 23 using MDCT, 10 MRI (including three reports with DWI and three studies with WB-DWI), and 16 using FDG PET/CT (including seven studies with CECT), were evaluated. On a per-patient basis, FDG PET/CT had the highest sensitivity (93.7%) when compared to MRI (82.7%) and MDCT (79.7%). Specificity estimates were high for all imaging modalities (92.1%, 90.3%, and 91.5% for MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT, respectively). Both FDG PET/CT and MRI have comparably higher per-patient diagnostic accuracy for the detection of PMs when compared to MDCT.

No differences in the diagnostic performance between MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT were found on a per-lesion basis. MRI had the highest sensitivity (92.6%), when compared to MDCT (70.1%) and FDG PET/CT (58.3%), although our results are limited, due to the small number of MRI datasets (n = 3). Specificity estimates were comparably high for all imaging modalities (90.2%, 90.3%, and 92.6% for MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT, respectively). Based on the results of this meta-analysis, FDG PET/CT and MRI had higher sensitivity compared to MDCT in the detection of PMs in OC.

Similar to our results, a recently published meta-analysis reported comparable diagnostic performance for DWI MRI and FDG PET/CT, higher than that of CT for the detection of PMs in ovarian and gastrointestinal cancer patients [47]. This review was based on 28 articles, including 20, 7, and 10 CT, DWI MRI, and FDG PET/CT datasets, respectively. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 68% and 88% for CT, 92% and 85% for DWI MRI, and 80% and 90% for FDG PET/CT [47].

MDCT is routinely used for the preoperative imaging of primary OC, with a reported staging accuracy of up to 94% [1,3,5,6,18,19,20,21,69,79]. Portal venous phase and water density oral contrast usually provide detailed mapping of PMs [1,69]. MDCT is also used for the evaluation of any persistence of disease after CRS and during follow-up, with a sensitivity and specificity of 58–84% and 59–100%, respectively, in the detection of OC recurrence [1,69,70,80].

The main advantages of MDCT include the following: wide availability, rapid scanning, increased volume coverage, excellent spatial resolution, robustness, and reproducibility of image acquisition. CT is devoid of misregistration artifacts and allows the acquisition of thin sections and the creation of high-resolution MPRs, improving the detection of small PMs, especially when a large amount of ascites is present, and the detailed exploration of curved peritoneal surfaces [18,19,20,21,67,69,70,81,82,83,84,85]. Coronal reformations improve the assessment of hemidiaphragms, hepatic and splenic surfaces, and paracolic gutters and the evaluation of the extent of omental disease. Sagittal MPRs improve the assessment of the hemidiaphragms, the Douglas pouch, the vaginal cuff, the peritoneal surface of the bladder, and the rectosigmoid colon [83,84,85]. The use of multiplanar reformations was reported in 11 articles in this meta-analysis, although comparative studies on the diagnostic performance of axial images versus MPRs in the detection of PMs were not performed due to limited data [27,52,56,57,59,65,67,69,70,73,78].

However, CT has limitations, including poor soft tissue contrast and reduced sensitivity for the detection of small PMs (<5 mm) and those in certain anatomical locations (e.g., mesentery and bowel serosa), especially in the absence of ascites [3,13,18,19,20,21,25,26,66,67,69,70,73,81,82]. Subgroup analysis including PMs of different sizes was not performed in the present review, due to inadequate relevant data.

MDCT comprised the largest dataset in our meta-analysis, allowing a comprehensive assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of the technique in the detection of PMs in different abdominopelvic regions. The highest MDCT detection rates were noted at the left hypochondrium (AR3), the central abdomen (AR0), the diaphragm, the pelvis (AR5–7 and AR6), and the left lumbar region (AR4). Our observations are primarily related to the advantages of MDCT technology, namely, the acquisition of thin slices and the creation of high-resolution reformations, resulting in an improvement in the evaluation of curved structures, such as the undersurface of the diaphragms, the paracolic gutter, and the pelvis [3,19]. Similar to published data, this review confirmed the low diagnostic performance of CT in the colon and the mesentery [3,13,20,25,26,73,81]. The detection of early mesenteric involvement or small-sized serosal bowel PMs may be problematic, as CT signs may be subtle, especially in the absence of adequate bowel distention [3].

Based on the analysis of 10 datasets, MRI proved more accurate compared to MDCT for the detection of PMs, on a per-patient basis. The use of fat suppression, delayed contrast-enhanced sequences, and DWI contribute to the improvement in the accuracy of MRI in the detection of PMs [3,5,16,20,21,30,31,32,33,34,35,66,69,86,87,88,89,90,91]. MRI allows better detection of subcentimeter PMs and PC involving certain anatomic areas, such as the bowel serosal surface, the pelvis, the right hypochondrium, and the mesentery. The interobserver agreement of MRI has also been reported to be higher compared to CT in most ARs [31,81]. Although the diagnostic performance of MRI was only assessed in three ARs, including the central abdomen (AR0), the diaphragm, and the mesentery, our systematic review found that MRI was more accurate in the bowel mesentery.

Normal peritoneal enhancement is equal to or less than that of the liver. Contrast enhancement greater than the liver is abnormal and may represent the only finding suggestive of PC. This sign is not always detected by MDCT; however, it is readily appreciated by MRI on delayed fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced imaging [3,5,20,81,88]. The sensitivity of MRI for PMs has been reported to increase by using DWI in combination with conventional MRI sequences, even in the absence of ascites. The increased contrast between the hyperintense hypercellular implants against the surrounding hypointense normal tissues enhances the detectability of PC by DWI [5,20,21,31,81,86,87,88,89].

No direct comparison between the accuracy of conventional MRI sequences and DWI was performed in this analysis, due to limited data.

Limitations of MRI are related to the high cost and long examination time, motion artifacts, lack of routine use of intraluminal contrast agents, and need for experience in image acquisition and interpretation [1,20,81,92]. MRI is also limited by its ability to detect small, calcified PMs, which are easily detected by MDCT. Disadvantages related to DWI are due to the low spatial resolution; presence of false-positives, attributed to densely cellular tissue, such as fibrosis, bowel mucosa, endometrium, and abscess; and false-negatives, attributed to mucinous carcinomas and well-differentiated malignancies [1,20].

Similar to MRI, this meta-analysis showed that FDG PET/CT was more sensitive than MDCT in the assessment of PC in OC on a per-patient basis. The main advantage of the technique is the whole-body coverage. FDG PET/CT can detect small PMs; evaluate all peritoneal compartments, even those inaccessible during surgery, such as the subdiaphragmatic peritoneal surfaces and the bowel mesentery; better assess ascites; and discriminate nodular peritoneal implants from the intestinal loops [1,5,17,30,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,63,67,68,69,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101]. The present review showed that FDG PET/CT had the highest detection rates in the central abdomen (AR0), the right hypochondrium (AR1), and the pelvis (AR5–7).

FDG PET/CT disadvantages are related to limited spatial resolution in the detection of small PMs (<5 mm), difficulty in the evaluation of diffuse peritoneal disease, presence of tissues with low FDG avidity, such as mucinous tumors, and possible discrepancy in lesion location between CT and PET/CT caused by respiratory movements and intestinal peristalsis. False positives may be due to inflammation, infection, and benign conditions or the normal physiological activity in the bowel, gallbladder, vessels, ureters, and urinary bladder. Shortcomings of PET/CT also include the limited availability and the high cost [5,67,68,101].

Complete resection of all macroscopic peritoneal implants has been proven to be the single most important independent prognostic factor in OC. Diagnostic laparoscopy can provide a definitive histologic diagnosis and detailed information on the extent of PC. However, up to 40% of women may be understaged surgically as small PMs in areas such as the subdiaphragmatic surfaces, the porta hepatis, or the hepatorenal fossa are not easily accessible. In addition, diagnostic laparoscopy has been associated with a high incidence of port-site metastases, although these do not worsen the patient’s prognosis [1,79]. Preoperative diagnostic work-up with CT, MRI, or FDG PET/CT is vital in the assessment of the extent of PC in OC [1,79].

Tumor heterogeneity in OC at a cellular and genetic level is a well-known phenomenon that cannot be thoroughly evaluated using conventional imaging data. Quantitative semi-automated and automated methods based on artificial intelligence techniques have been developed, which can be applied to routine medical images to assess tumor heterogeneity. The use of radiomics and radiogenomics may be helpful in the future in predicting OC genotype and biology and in assessing treatment response, clinical outcome, and patient survival [102,103,104,105,106]. Based on preliminary data, MRI and CT-based radiomics have been reported to predict the presence of PMs in OC [107,108,109,110].

This meta-analysis has inherent limitations, mainly related to publication bias and study heterogeneity. Our systematic review was limited to the PubMed database, including published studies reporting a “positive effect” that might overestimate the actual magnitude of an effect. However, study quality grading showed that most of the studies included in the analysis were of high to good quality.

Heterogeneity among included patient groups is another shortcoming, due to differences in primary outcome (primary staging and recurrent disease). Subgroup analysis assessing the differences in the diagnostic performance of MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT in the detection of PMs between primary and recurrent OC was not performed, due to the lack of relevant data. Heterogeneity in study design, imaging methodologies (including scanners, protocols, sequences, and intravenous/oral contrast), reader experience, and reference standards (ranging from histopathologic confirmation to surgical findings and imaging follow-up) is another limitation. The standardization of imaging techniques and consensus on the interpretation criteria for PMs across different centers would facilitate more accurate and reliable assessments. Finally, no data on the cost-effectiveness of MDCT, MRI, and FDG PET/CT were analyzed. Future research should focus on evaluating the cost-effectiveness of these imaging modalities in detecting peritoneal metastases and their impact on treatment decision making.

5. Conclusions

Peritoneal metastases represent a common finding in women with primary or recurrent OC. Preoperative diagnostic work-up with MDCT, MRI, or FDG PET/CT is mandatory to define the extent of the disease, predict the likelihood of optimal cytoreduction, identify potentially unresectable or difficult disease locations, requiring surgical technique modifications, and select patients who may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.

Based on the results of this meta-analysis, FDG PET/CT and MRI had a higher diagnostic performance in the detection of PMs compared to MDCT on a per-patient analysis. No differences between the three imaging modalities were found on a per-lesion basis.

In summary, while FDG PET/CT and MRI can be considered equivalent alternatives for the detection of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer, the limitations of the included studies and the need for standardization should be considered. Future research addressing these limitations and exploring cost-effectiveness would contribute to the improvement in clinical practice in the management of ovarian cancer.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers16081467/s1, Table S1: Results of the per-patient analysis for MDCT (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value; MPR: multiplanar reformation); Table S2: Results of the per-patient analysis for MRI (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value; PMs: peritoneal metastases); Table S3: Results of the per-patient analysis for FDG PET/CT (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value); Table S4: Results of the per-region analysis for MDCT (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value); Table S5: Results of the per-region analysis for MRI (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value); Table S6: Results of the per-region analysis for FDG PET/CT (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value); Table S7: Results of the per-patient analysis for MDCT in different abdominopelvic regions (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value; ARs: abdominopelvic regions; MPR: multiplanar reformation); Table S8: Results of the per-patient analysis for MRI in different abdominopelvic regions (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value); Table S9: Results of the per-patient analysis for FDG PET/CT in different abdominopelvic regions (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value); Table S10: Results of the per-region analysis for MDCT in different abdominopelvic regions (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value; ARs: abdominopelvic regions); Table S11: Results of the per-region analysis for FDG PET-CT in different abdominopelvic regions (TP: true positive, FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; PPV: positive-predictive value; NPV: negative-predictive value; ARs: abdominopelvic regions). References [26,27,30,42,44,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

A.C.T., M.T. and T.S. wrote the review. M.T. and T.S. prepared the figures. A.C.T., G.A. and M.I.A. reviewed and edited the draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in the context of the present review.

Abbreviations

| OC | ovarian cancer |

| PDS | primary debulking surgery |

| IDS | interval debulking surgery |

| NAC | neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| PMs | peritoneal metastases |

| PCI | peritoneal carcinomatosis index |

| ARs | abdominopelvic regions |

| PC | peritoneal carcinomatosis |

| MDCT | multidetector CT |

| DWI | diffusion-weighted imaging |

| PRISMA | preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis |

| FDG | fluorodeoxyglucose |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| TP | true-positive |

| FN | false-negative |

| FP | false-positive |

| TN | true-negative |

| QUADAS | quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies |

| MPR | multiplanar reformation |

| WB-DWI | whole-body DWI |

| CECT | contrast-enhanced CT |

| CI | confidence interval |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| NPV | negative predictive value |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| DOR | diagnostic odds ratio |

| SROC | summary receiver operating characteristic curve |

References

- Expert Panel on Women’s Imaging; Kang, S.K.; Reinhold, C.; Atri, M.; Benson, C.B.; Bhosale, P.R.; Jhingran, A.; Lakhman, Y.; Maturen, K.E.; Nicola, R.; et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Staging and Follow-Up of Ovarian Cancer. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2018, 15, S198–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2024/2024-cancer-facts-and-figures-acs.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Nougaret, S.; Addley, H.C.; Colombo, P.E.; Fujii, S.; Al Sharif, S.S.; Tirumani, S.H.; Jardon, K.; Sala, E.; Reinhold, C. Ovarian carcinomatosis: How the radiologist can help plan the surgical approach. Radiographics 2012, 32, 1775–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, E.J.; Yun, M.J.; Oh, Y.T.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.; Jung, Y.W.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, Y.T. Diagnosis and staging of primary ovarian cancer: Correlation between PET/CT, Doppler US, and CT or MRI. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 116, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, H.; Lee, E.Y.P.; Chiu, K.; Chang, C. The emerging roles of functional imaging in ovarian cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Clin. Radiol. 2018, 73, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstner, R.; Meissnitzer, M.; Cunha, T.M. Update on Imaging of Ovarian Cancer. Curr. Radiol. Rep. 2016, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstner, R.; Sala, E.; Kinkel, K.; Spencer, J.A. European Society of Urogenital Radiology, ESUR guidelines: Ovarian cancer staging and follow-up. Eur. Radiol. 2010, 20, 2773–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinagare, A.B.; Sadowski, E.A.; Park, H.; Brook, O.R.; Forstner, R.; Wallace, S.K.; Horowitz, J.M.; Horowitz, N.; Javitt, M.; Jha, P.; et al. Ovarian cancer reporting lexicon for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging developed by the SAR Uterine and Ovarian Cancer Disease-Focused Panel and the ESUR Female Pelvic Imaging Working Group. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 3220–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadi, S.; Ganeshan, D.M.; Qayyum, A.; Iyer, R.B.; Bhosale, P. Ovarian Cancer, the Revised FIGO Staging System, and the Role of Imaging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2016, 206, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghirardi, V.; Fagotti, A.; Ansaloni, L.; Valle, M.; Roviello, F.; Sorrentino, L.; Accarpio, F.; Baiocchi, G.; Piccini, L.; De Simone, M.; et al. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Pathway of Advanced Ovarian Cancer with Peritoneal Metastases. Cancers 2023, 15, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armbrust, R.; Ledwon, P.; Von Rüsten, A.; Schneider, C.; Sehouli, J. Primary Treatment Results in Patients with Ovarian, Fallopian or Peritoneal Cancer-Results of a Clinical Cancer Registry Database Analysis in Germany. Cancers 2022, 24, 4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasqual, E.M.; Londero, A.P.; Robella, M.; Tonello, M.; Sommariva, A.; De Simone, M.; Bacchetti, S.; Baiocchi, G.; Asero, S.; Coccolini, F.; et al. Repeated Cytoreduction Combined with Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) in Selected Patients Affected by Peritoneal Metastases: Italian PSM Oncoteam Evidence. Cancers 2023, 15, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriazi, S.; Kaye, S.B.; DeSouza, N.M. Imaging ovarian cancer and peritoneal metastases-current and emerging techniques. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 7, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, S.; Del Grande, M.; Manganaro, L.; Papadia, A.; Del Grande, F. Imaging before cytoreductive surgery in advanced ovarian cancer patients. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nougaret, S.; Sadowski, E.; Lakhman, Y.; Rousset, P.; Lahaye, M.; Worley, M.; Sgarbura, O.; Shinagare, A.B. The BUMPy road of peritoneal metastases in ovarian cancer. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2022, 103, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, T.; Adejolu, M.; DeSouza, N.M. Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Ovarian Cancer: Exploiting Strengths and Understanding Limitations. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.Y.P.; An, H.; Tse, K.Y.; Khong, P.L. Molecular Imaging of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis in Ovarian Carcinoma. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020, 215, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, F.V.; Choi, P.H.; Gougoutas, C.A.; Pothuri, B.; Venkatraman, E.; Chi, D.; Bergman, A.; Hricak, H. Peritoneal metastases: Detection with spiral CT in patients with ovarian cancer. Radiology 2002, 223, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsili, A.C.; Naka, C.; Argyropoulou, M.I. Multidetector computed tomography in diagnosing peritoneal metastases in ovarian carcinoma. Acta Radiol. 2021, 62, 1696–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, C.M.; Sahdev, A.; Reznek, R.H. CT, MRI and PET imaging in peritoneal malignancy. Cancer Imaging 2011, 11, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iafrate, F.; Ciolina, M.; Sammartino, P.; Baldassari, P.; Rengo, M.; Lucchesi, P.; Sibio, S.; Accarpio, F.; Di Giorgio, A.; Laghi, A. Peritoneal carcinomatosis: Imaging with 64-MDCT and 3T MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging. Abdom. Imaging 2012, 37, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qayyum, A.; Coakley, F.V.; Westphalen, A.C. Role of CT and MR imaging in predicting optimal cytoreduction of newly diagnosed primary epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 96, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquet, P.; Sugarbaker, P.H. Clinical research methodologies in diagnosis and staging of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. In Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: Principles of Management; Sugarbaker, P.H., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 82, pp. 359–374. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla Ahmed, S.; Abou-Taleb, H.; Ali, N.; Badary, D.M. Accuracy of radiologic- laparoscopic peritoneal carcinomatosis categorization in the prediction of surgical outcome. Br. J. Radiol. 2019, 92, 20190163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, I.J.; Van de Laar, R.; Kruitwagen, R.F.; Bakers, F.C.; Ploegmakers, M.J.; Pappot, T.W.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Massuger, L.F.A.G.; Zusterzeel, P.L.M.; Gorp, T.V. Prediction of incomplete primary debulking surgery in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: An external validation study of three models using computed tomography. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 140, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, S.; Lazaridis, A.; Evangelou, M.; Jones, B.; Nixon, K.; Kyrgiou, M.; Gabra, H.; Rockall, A.; Fotopoulou, C. Correlation of pre-operative CT findings with surgical & histological tumor dissemination patterns at cytoreduction for primary advanced and relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer: A retrospective evaluation. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 143, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- An, H.; Chiu, K.W.H.; Tse, K.Y.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Khong, P.L.; Lee, E.Y.P. The Value of Contrast-Enhanced CT in the Detection of Residual Disease After Neo-Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. Acad. Radiol. 2020, 27, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, R.; Traill, Z.; Valenti, G.; Ferrari, F.; Gubbala, K.; Campanile, R.G. A prospective study on the diagnostic pathway of patients with stage IIIC-IV ovarian cancer: Exploratory laparoscopy (EXL) + CT scan VS. CT scan. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onda, T.; Tanaka, Y.O.; Kitai, S.; Manabe, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Hasumi, Y.; Miyamoto, K.; Ogawa, G.; Satoh, T.; Saito, T.; et al. Stage III disease of ovarian, tubal and peritoneal cancers can be accurately diagnosed with pre-operative CT. Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0602. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 51, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, M.S.; Petersen, L.K.; Blaakaer, J.; Marinovskij, E.; Rosenkilde, M.; Andersen, G.; Bouchelouche, K.; Iversen, L.H. Assessment of peritoneal metastases with DW-MRI, CT, and FDG PET/CT before cytoreductive surgery for advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 2134–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehniger, J.; Thomas, S.; Lengyel, E.; Liao, C.; Tenney, M.; Oto, A.; Yamada, S.D. A prospective study evaluating diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) in the detection of peritoneal carcinomatosis in suspected gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 142, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriazi, S.; Collins, D.J.; Morgan, V.A.; Giles, S.L.; DeSouza, N.M. Diffusion-weighted imaging of peritoneal disease for noninvasive staging of advanced ovarian cancer. Radiographics 2010, 30, 1269–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, E.; Kataoka, M.Y.; Priest, A.N.; Gill, A.B.; McLean, M.A.; Joubert, I.; Graves, M.J.; Crawford, R.A.F.; Jimenez-Linan, M.; Earl, H.M.; et al. Advanced ovarian cancer: Multiparametric MR imaging demonstrates response- and metastasis-specific effects. Radiology 2012, 263, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, R.N.; Barone, R.M. Combined diffusion-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced MRI can accurately predict the peritoneal cancer index preoperatively in patients being considered for cytoreductive surgical procedures. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engbersen, M.P.; Van’ T Sant, I.; Lok, C.; Lambregts, D.M.J.; Sonke, G.S.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Van Driel, W.J.; Lahaye, M.J. MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging to predict feasibility of complete cytoreduction with the peritoneal cancer index (PCI) in advanced stage ovarian cancer patients. Eur. J. Radiol. 2019, 114, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannu, H.K.; Bristow, R.E.; Cohade, C.; Fishman, E.K.; Wahl, R.L. PET-CT in recurrent ovarian cancer: Initial observations. Radiographics 2004, 24, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risum, S.; Høgdall, C.; Loft, A.; Berthelsen, A.K.; Høgdall, E.; Nedergaard, L.; Lundvall, L.; Engelholm, S.A. The diagnostic value of PET/CT for primary ovarian cancer-A prospective study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrall, M.M.; DeLoia, J.A.; Gallion, H.; Avril, N. Clinical use of combined positron emission tomography and computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) in recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soussan, M.; Wartski, M.; Cherel, P.; Fourme, E.; Goupil, A.; Le Stanc, E.; Callet, N.; Alexandre, J.; Pecking, A.; Alberini, J. Impact of FDG PET-CT imaging on the decision making in the biologic suspicion of ovarian carcinoma recurrence. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 108, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulham, M.J.; Carter, J.; Baldey, A.; Hicks, R.J.; Ramshaw, J.E.; Gibson, M. The impact of PET-CT in suspected recurrent ovarian cancer: A prospective multi-centre study as part of the Australian PET Data Collection Project. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 112, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boria, F.; Chiva, L.; Carbonell, M.; Gutierrez, M.; Sancho, L.; Alcazar, A.; Coronado, M.; Hernández Gutiérrez, A.; Zapardiel, I. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) predictive score for complete resection in primary cytoreductive surgery. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Liu, S.; Ju, X.; Chen, X.; Li, R.; Bi, R.; Wu, X. Diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT scan for peritoneal metastases in advanced ovarian cancer. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2021, 11, 3392–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvallée, J.; Rossard, L.; Bendifallah, S.; Touboul, C.; Collinet, P.; Bricou, A.; Huchon, C.; Lavoue, V.; Body, G.; Ouldamer, L. Accuracy of peritoneal carcinomatosis extent diagnosis by initial FDG PET CT in epithelial ovarian cancer: A multicentre study of the FRANCOGYN research group. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 49, 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallet, E.; Angeles, M.A.; Cabarrou, B.; Chardin, D.; Viau, P.; Frigenza, M.; Navarro, A.S.; Ducassou, A.; Betrian, S.; Martínez-Gómez, C.; et al. Performance of Multiparametric Functional Imaging to Assess Peritoneal Tumor Burden in Ovarian Cancer. Nucl. Med. 2021, 46, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the recurrence of epithelial ovarian cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1003465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghi, A.; Bellini, D.; Rengo, M.; Accarpio, F.; Caruso, D.; Biacchi, D.; Di Giorgio, A.; Sammartino, P. Diagnostic performance of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for detecting peritoneal metastases: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiol. Med. 2017, 122, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van ‘t Sant, I.; Engbersen, M.P.; Bhairosing, P.A.; Lambregts, D.M.J.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Van Driel, W.J.; Aalbers, A.G.J.; Kok, N.F.M.; Lahaye, M.J. Diagnostic performance of imaging for the detection of peritoneal metastases: A meta-analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 3101–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, P.; Pan, L.L.; Wu, S.Q.; Sun, L.; Huang, G. CA 125, PET alone, PET-CT, CT and MRI in diagnosing recurrent ovarian carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2009, 71, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M. QUADAS-2 Group, QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tempany, C.M.; Zou, K.H.; Silverman, S.G.; Brown, D.L.; Kurtz, A.B.; McNeil, B.J. Staging of advanced ovarian cancer: Comparison of imaging modalities-report from the Radiological Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology 2000, 215, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannu, H.K.; Horton, K.M.; Fishman, E.K. Thin section dual-phase multidetector-row computed tomography detection of peritoneal metastases in gynecologic cancers. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2003, 27, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricke, J.; Sehouli, J.; Hach, C.; Hänninen, E.L.; Lichtenegger, W.; Felix, R. Prospective evaluation of contrast-enhanced MRI in the depiction of peritoneal spread in primary or recurrent ovarian cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2003, 13, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannu, H.K.; Cohade, C.; Bristow, R.E.; Fishman, E.K.; Wahl, R.L. PET-CT detection of abdominal recurrence of ovarian cancer: Radiologic-surgical correlation. Abdom. Imaging 2004, 29, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.K.; Park, B.K.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, B.G.; Han, H.J. Detection of recurrent ovarian cancer at MRI: Comparison with integrated PET/CT. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2007, 31, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, K.; Murakami, K.; Yamasaki, E.; Kaji, Y.; Fukasawa, I.; Inaba, N.; Sugimura, K. Diagnostic accuracy of integrated FDG-PET/contrast-enhanced CT in staging ovarian cancer: Comparison with enhanced CT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2008, 35, 1912–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, K.; Murakami, K.; Yamasaki, E.; Domeki, Y.; Kaji, Y.; Fukasawa, I.; Inaba, N.; Suganuma, N.; Sugimura, K. Performance of integrated FDG-PET/contrast-enhanced CT in the diagnosis of recurrent ovarian cancer: Comparison with integrated FDG-PET/non-contrast-enhanced CT and enhanced CT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2008, 35, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.J.; Lim, M.C.; Bae, J.; Cho, K.S.; Jung, D.C.; Kang, S.; Yoo, C.W.; Seo, S.S.; Park, S.Y. Region-based diagnostic performance of multidetector CT for detecting peritoneal seeding in ovarian cancer patients. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 283, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metser, U.; Jones, C.; Jacks, L.M.; Bernardini, M.Q.; Ferguson, S. Identification and quantification of peritoneal metastases in patients with ovarian cancer with multidetector computed tomography: Correlation with surgery and surgical outcome. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Iaco, P.; Musto, A.; Orazi, L.; Zamagni, C.; Rosati, M.; Allegri, V.; Cacciari, N.; Al-Nahhas, A.; Rubello, D.; Venturoli, S.; et al. FDG-PET/CT in Advanced Ovarian Cancer Staging: Value and Pitfalls in Detecting Lesions in Different Abdominal and Pelvic Quadrants Compared with Laparoscopy. Eur. J. Radiol. 2011, 80, e98–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanli, Y.; Turkmen, C.; Bakir, B.; Iyibozkurt, C.; Ozel, S.; Has, D.; Yilmaz, E.; Topuz, S.; Yavuz, E.; Unal, S.N.; et al. Diagnostic value of PET/CT is similar to that of conventional MRI and even better for detecting small peritoneal implants in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2012, 33, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, M.; Garcia-Flores, J.R.; Jimenez, M.; Alvarez-Moreno, E.; De Haro, M.; Gonzalez-Cortijo, L.; Hernandez-Cortes, G.; Martinez-Vega, V.; De La Cuesta, R.S. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of intra-abdominal sites of implants to predict likelihood of suboptimal cytoreductive surgery in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Eur. Radiol. 2013, 23, 2636–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynninen, J.; Kemppainen, J.; Lavonius, M.; Virtanen, J.; Matomäki, J.; Oksa, S.; Carpén, O.; Grénman, S.; Seppänen, M.; Auranen, A. A prospective comparison of integrated FDG-PET/contrast-enhanced CT and contrast-enhanced CT for pretreatment imaging of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 131, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.H.; Won, K.S.; Zeon, S.K.; Ahn, B.C.; Gayed, I.W. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with ovarian cancer. Enhanced CT versus 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2013, 38, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzei, M.A.; Khader, L.; Cirigliano, A.; Cioffi Squitieri, N.; Guerrini, S.; Forzoni, B.; Marrelli, D.; Roviello, F.; Mazzei, F.G.; Volterrani, L. Accuracy of MDCT in the preoperative definition of Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) in patients with advanced ovarian cancer who underwent peritonectomy and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Abdom. Imaging 2013, 38, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michielsen, K.; Vergote, I.; Op de Beeck, K.; Amant, F.; Leunen, K.; Moerman, P.; Deroose, C.; Souverijns, G.; Dymarkowski, S.; De Keyzer, F.; et al. Whole-body MRI with diffusion-weighted sequence for staging of patients with suspected ovarian cancer: A clinical feasibility study in comparison to CT and FDG-PET/CT. Eur. Radiol. 2014, 24, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S.; Meuli, R.A.; Achtari, C.; Prior, J.O. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in primary ovarian cancer staging: Comparison between MDCT, MRI, and 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2015, 40, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Lopez, V.; Cascales-Campos, P.A.; Gil, J.; Frutos, L.; Andrade, R.J.; Fuster-Quiñonero, M.; Feliciangeli, E.; Gil, E.; Parrilla, P. Use of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in the preoperative evaluation of patients diagnosed with peritoneal carcinomatosis of ovarian origin, candidates to cytoreduction and hipec. A pending issue. Eur. J. Radiol. 2016, 85, 1824–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodolfino, E.; Devicienti, E.; Miccò, M.; Del Ciello, A.; Di Giovanni, S.E.; Giuliani, M.; Conte, C.; Gui, B.; Valentini, A.L.; Bonomo, L. Diagnostic accuracy of MDCT in the evaluation of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer: Is delayed enhanced phase really effective? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 4426–4434. [Google Scholar]

- Tawakol, A.; Abdelhafez, Y.G.; Osama, A.; Hamada, E.; El Refaei, S. Diagnostic performance of 18F-FDG PET/contrast-enhanced CT versus contrast-enhanced CT alone for post-treatment detection of ovarian malignancy. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2016, 37, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerci, Z.C.; Sakarya, D.K.; Yetimalar, M.H.; Bezircioglu, I.; Kasap, B.; Baser, E.; Yucel, K. Computed tomography as a predictor of the extent of the disease and surgical outcomes in ovarian cancer. Ginekol. Pol. 2016, 87, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bagul, K.; Vijaykumar, D.K.; Rajanbabu, A.; Antony, M.A.; Ranganathan, V. Advanced Primary Epithelial Ovarian and Peritoneal Carcinoma-Does Diagnostic Accuracy of Preoperative CT Scan for Detection of Peritoneal Metastatic Sites Reflect into Prediction of Suboptimal Debulking? A Prospective Study. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 8, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, K.; Dresen, R.; Vanslembrouck, R.; De Keyzer, F.; Amant, F.; Mussen, E.; Leunen, K.; Berteloot, P.; Moerman, P.; Vergote, I.; et al. Diagnostic value of whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI compared to computed tomography for pre-operative assessment of patients suspected for ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 83, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajan, J.; Kuriakose, S.; Rajendran, V.R.; Sumangaladevi, D. Radiological and surgical correlation of disease burden in advanced ovarian cancer using peritoneal carcinomatosis index. Indian. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcázar, J.L.; Caparros, M.; Arraiza, M.; Mínguez, J.A.; Guerriero, S.; Chiva, L.; Jurado, M. Pre-operative Assessment of Intra-Abdominal Disease Spread in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: A Comparative Study between Ultrasound and Computed Tomography. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Abou-Taleb, H.; Yehia, A.; El Malek, N.A.A.; Siefeldein, G.S.; Badary, D.M.; Jabir, M.A. The accuracy of multi-detector computed tomography and laparoscopy in the prediction of peritoneal carcinomatosis index score in primary ovarian cancer. Acad. Radiol. 2019, 26, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoi, T.T.; Chiu, K.W.H.; Chu, M.Y.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Lee, E.Y.P. Metabolic active peritoneal sites affect tumor debulking in ovarian and peritoneal cancers. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischerova, D.; Pinto, P.; Burgetova, A.; Masek, M.; Slama, J.; Kocian, R.; Frühauf, F.; Zikan, M.; Dusek, L.; Dundr, P.; et al. Preoperative staging of ovarian cancer: Comparison between ultrasound, CT and whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI (ISAAC study). Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 59, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, N.; Sessa, C.; du Bois, A.; Ledermann, J.; McCluggage, W.G.; McNeish, I.; Morice, P.; Pignata, S.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Vergote, I.; et al. ESMO-ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: Pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 672–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, H.; Jung, D.C.; Lee, J.Y.; Nam, E.J.; Kang, W.J.; Oh, Y.T. Patterns of initially overlooked recurrence of peritoneal lesions in patients with advanced ovarian cancer on postoperative multi-detector row CT. Acta Radiol. 2019, 60, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadelhak, B.; Tawfik, A.M.; Saleh, G.A.; Batouty, N.M.; Sobh, D.M.; Hamdy, O.; Refky, B. Extended abdominopelvic MRI versus CT at the time of adnexal mass characterization for assessing radiologic peritoneal cancer index (PCI) prior to cytoreductive surgery. Abdom. Radiol. 2019, 44, 2254–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstner, R. Radiological staging of ovarian cancer: Imaging findings and contribution of CT and MRI. Eur. Radiol. 2007, 17, 3223–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannu, H.K.; Bristow, R.E.; Montz, F.J.; Fishman, E.K. Multidetector CT of peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. Radiographics 2003, 23, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franiel, T.; Diederichs, G.; Engelken, F.; Elgeti, T.; Rost, J.; Rogalla, P. Multi-detector CT in peritoneal carcinomatosis: Diagnostic role of thin slices and multiplanar reconstructions. Abdom. Imaging 2009, 34, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, D.; Catalano, C.; Baski, M.; De Martino, M.; Geiger, D.; Di Giorgio, A.; Sibio, S.; Passariello, R. 64-Section multi-detector row CT in the preoperative diagnosis of peritoneal carcinomatosis: Correlation with histopathological findings. Abdom. Imaging 2010, 35, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, R.N.; Sebrechts, C.P.; Barone, R.M.; Muller, W. Diffusion-weighted MRI of peritoneal tumors: Comparison with conventional MRI and surgical and histopathologic findings: A feasibility study. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 193, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namimoto, T.; Awai, K.; Nakaura, T.; Yanaga, Y.; Hirai, T.; Yamashita, Y. Role of diffusion-weighted imaging in the diagnosis of gynecological diseases. Eur. Radiol. 2009, 19, 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priest, A.N.; Gill, A.B.; Kataoka, M.; McLean, M.A.; Joubert, I.; Graves, M.J.; Griffiths, J.R.; Crawford, R.A.F.; Earl, H.; Brenton, J.D.; et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in ovarian cancer: Initial experience at 3 tesla in primary and metastatic disease. Magn. Reson. Med. 2010, 63, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, R.N.; Barone, R.M. Imaging for Peritoneal Metastases. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 27, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.L.; He, L.; Zhu, Y.C.; Wu, K.; Yuan, F. Comparison between multi-slice spiral CT and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of peritoneal metastasis in primary ovarian carcinoma. Oncol. Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, Y.; Ichikawa, T.; Motosugi, U.; Kimura, K.; Sou, H.; Sano, K.; Araki, T. Diagnosis of peritoneal dissemination: Comparison of 18F-FDG PET/CT, diffusion-weighted MRI, and contrast-enhanced MDCT. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2001, 196, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torkzad, M.R.; Casta, N.; Bergman, A.; Ahlström, H.; Påhlman, L.; Mahteme, H. Comparison between MRI and CT in prediction of peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) in patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery in relation to the experience of the radiologist. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 111, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sironi, S.; Messa, C.; Mangili, G.; Zangheri, B.; Aletti, G.; Garavaglia, E.; Vigano, R.; Picchio, M.; Taccagni, G.; Del Maschio, A.; et al. Integrated FDG PET/CT in patients with persistent ovarian cancer: Correlation with histologic findings. Radiology 2004, 233, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauth, E.A.; Antoch, G.; Stattaus, J.; Kuehl, H.; Veit, P.; Bockisch, A.; Kimmig, R.; Forsting, M. Evaluation of integrated whole-body PET/CT in the detection of recurrent ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Radiol. 2005, 56, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, C.; Rubello, D.; Farsad, M.; De Iaco, P.; Sansovini, M.; Erba, P.; Rampin, L.; Mariani, G.; Fanti, S. (18)F-FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of recurrent ovarian cancer: A prospective study on forty-one patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2005, 31, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangili, G.; Picchio, M.; Sironi, S.; Vigano, R.; Rabaiotti, E.; Bornaghi, D.; Bettinardi, V.; Crivellaro, C.; Messa, C.; Fazio, F. Integrated PET/CT as a first-line re-staging modality in patients with suspected recurrence of ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2007, 34, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellucci, P.; Perrone, A.M.; Picchio, M.; Ghi, T.; Farsad, M.; Nanni, C.; Messa, C.; Meriggiola, M.C.; Pelusi, G.; Al-Nahhas, A.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT in characterizing ovarian lesions and staging ovarian cancer: Correlation with transvaginal ultrasonography, computed tomography, and histology. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2007, 28, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, S.; Lee, S.I.; Horowitz, N.S.; Scott, J.A.; Fischman, A.J.; Simeone, J.F.; Fuller, A.F.; Hahn, P.F. PET-CT vs. CT alone in ovarian cancer recurrence. Abdom. Imaging 2008, 33, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfannenberg, C.; Konigsrainer, I.; Aschoff, P.; Oksüz, M.O.; Zieker, D.; Beckert, S.; Symons, S.; Nieselt, K.; Glatzle, J.; Weyhern, C.V.; et al. (18)F-FDG-PET/CT to select patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 16, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar Dhingra, V.; Kand, P.; Basu, S. Impact of FDG-PET and PET/CT imaging in the clinical decision-making of ovarian carcinoma: An evidence-based approach. Womens Health 2012, 8, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubini, G.; Altini, C.; Notaristefano, A.; Merenda, N.; Rubini, D.; Ianora, A.A.; Asabella, A.N. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in diagnosing peritoneal carcinomatosis in the restaging of patient with ovarian cancer as compared to contrast enhanced CT and tumor marker Ca-125. Rev. Esp. Med. Nucl. Imagen Mol. 2014, 33, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miceli, V.; Gennarini, M.; Tomao, F.; Cupertino, A.; Lombardo, D.; Palaia, I.; Curti, F.; Riccardi, S.; Ninkova, R.; Maccioni, F.; et al. Imaging of peritoneal carcinomatosis in advanced ovarian cancer: CT, MRI, radiomics features and resectability criteria. Cancers 2023, 15, 5827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nougaret, S.; Tardieu, M.; Vargas, H.A.; Reinhold, C.; Vande Perre, S.; Bonanno, N.; Sala, E.; Thomassin-Naggara, I. Ovarian cancer: An update on imaging in the era of radiomics. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2019, 100, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nougaret, S.; McCague, C.; Tibermacine, H.; Vargas, H.A.; Rizzo, S.; Sala, E. Radiomics and radiogenomics in ovarian cancer: A literature review. Abdom. Radiol. 2021, 46, 2308–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panico, C.; Avesani, G.; Zormpas-Petridis, K.; Rundo, L.; Nero, C.; Sala, E. Radiomics and Radiogenomics of Ovarian Cancer: Implications for Treatment Monitoring and Clinical Management. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 61, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, L.; Sahin, H.; Bateman, N.W.; Blazic, I.; Vargas, H.A.; Veeraraghavan, H.; Kirby, J.; Fevrier-Sullivan, B.; Freymann, J.B.; Jaffeet, C.C.; et al. Integration of proteomics with CT-based qualitative and radiomic features in high-grade serous ovarian cancer patients: An exploratory analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 4306–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.L.; Ren, J.L.; Yao, T.Y.; Zhao, D.; Niu, J. Radiomics based on multisequence magnetic resonance imaging for the preoperative prediction of peritoneal metastasis in ovarian cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 8438–8446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, C.; Jia, J.; Xu, H.; Dai, Y.; Feng, G.; Qin, C.; Bai, G.; Chen, S.; et al. Associating peritoneal metastasis with T2-weighted MRI images in epithelial ovarian cancer using deep learning and radiomics: A multicenter study. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2024, 59, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Lin, Z.; Lu, J.; Li, R.; Wu, L.; Deng, L.; Qiang, J.; Wu, X.; Gu, Y.; Li, H. Preoperative prediction of miliary changes in the small bowel mesentery in advanced high-grade serous ovarian cancer using MRI radiomics nomogram. Abdom. Radiol. 2023, 48, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Ma, J.; Cui, S.; Ye, Z. CT-based radiomics for the preoperative prediction of occult peritoneal metastasis in epithelial ovarian cancers. Acad. Radiol. 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).