Cross-Cultural Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

2.3. Ethics Issues

2.4. Measurement Development

2.4.1. Original Instrument

2.4.2. Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process

2.5. Reliability and Validity

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Data Analysis

3.2. Reliability and Validity

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

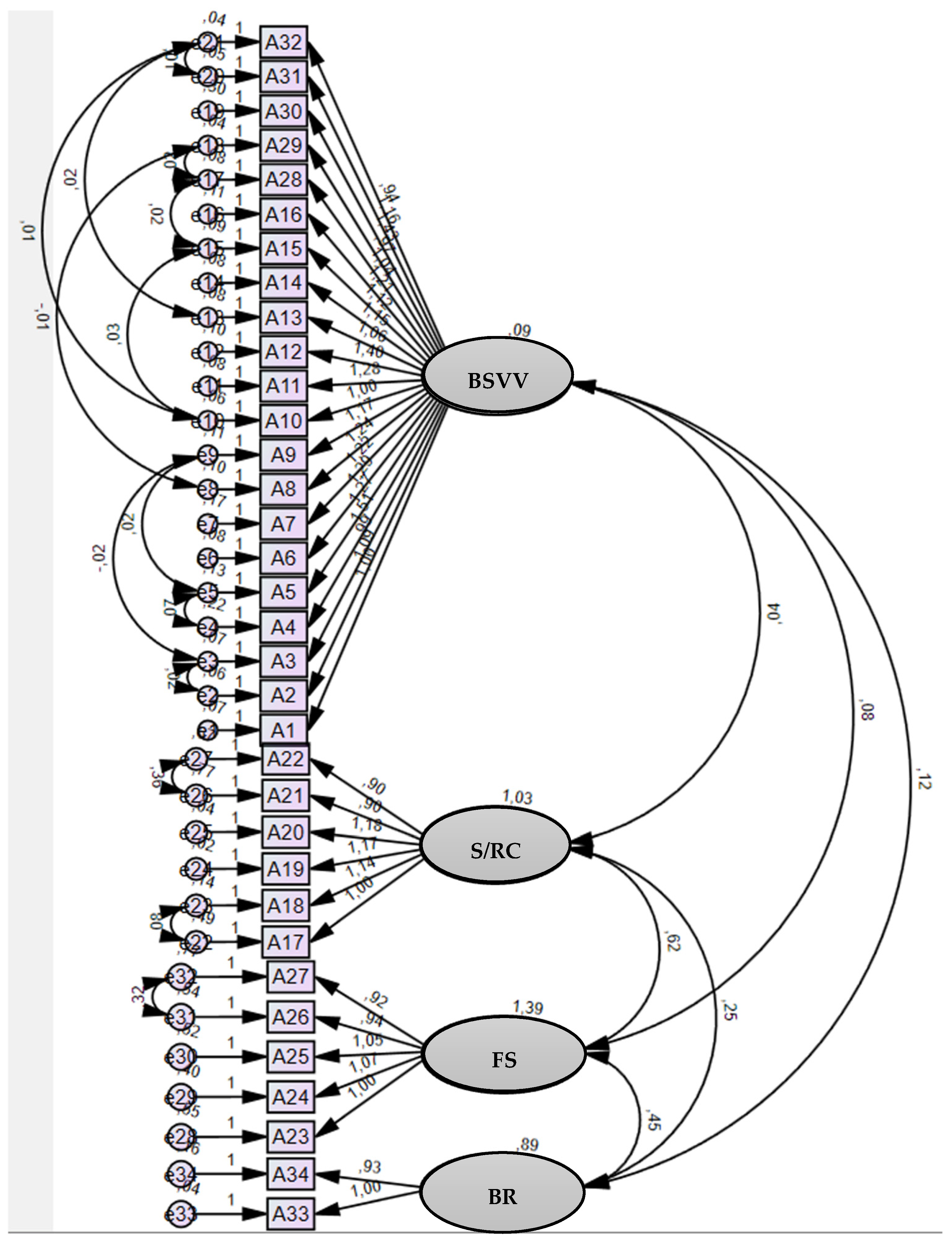

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Research Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lubjeko, B.G.; Wilson, B.J. Oncology Nursing Scope Standards of Practice; Oncology Nursing Society: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Charalambous, A.; Beadsmoore, A. Towards a Theory of Quality Nursing Care for Patients with Cancer through Hermeneutic Phenomenology. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2009, 13, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Quality Measures. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality/measures (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Understanding Quality Measurement. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Giardino, E.R. Evaluation and Outcomes. In Evaluation in Quality in Healthcare for DNPs; Springer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 94–111. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) National Cancer Policy Board. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care; Hewitt, M., Simone, J.V., Eds.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, M.; Coulter, A. Patient-Centred Care in the Nordic Countries. In Researching Patient Safety and Quality in Healthcare: A Nordic Perpective; Aase, K., Schibevaag, L., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Measuring What Matters: The Patient-Reported Indicator Surveys: Patient-Reported Indicators for Assessing Health System Performance; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelleri, J.C.; Zou, K.H.; Bushmakin, A.G.; Alvir, J.M.J.; Alemayehu, D.; Symonds, T. Introduction. In Patient-Reported Outcomes: Measurement, Implementation and Interpretation; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Casaca, P.; Schäfer, W.; Nunes, A.B.; Sousa, P. Using Patient-Reported Outcome Measures and Patient-Reported Experience Measures to Elevate the Quality of Healthcare. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2023, 35, mzad098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, T. Why PROMs and PREMs Matter? In Patient-Reported Outcomes and Experience: Measuring What We Want from PROMs and PREMs; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Papalois, Z.-A.; Papalois, V. Health-Related Quality of Life and Patient Reported Outcome Measures Following Transplantation Surgery. In Patient Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life in Surgery; Athanasiou, T., Patel, V., Darzi, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, A. Can Patients Assess the Quality of Health Care? BMJ 2006, 333, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsley, C.; Patel, S. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures and Patient-Reported Experience Measures. BJA Educ. 2017, 17, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, C.; Teede, H.; Watson, D.; Callander, E.J. Selecting and Implementing Patient-Reported Outcome and Experience Measures to Assess Health System Performance. JAMA Health Forum. 2022, 3, e220326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousoulou, M.; Suhonen, R.; Charalambous, A. Associations of Individualized Nursing Care and Quality Oncology Nursing Care in Patients Diagnosed with Cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 41, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalambous, A.; Adamakidou, T.; Cloconi, C.; Charalambous, M.; Tsitsi, T.; Vondráčková, L.; Bužgová, R. The Quality of Oncology Nursing Care: A Cross Sectional Survey in Three Countries in Europe. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 27, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, P.; Jesus, E.; Almeida, S.; Araújo, B. Relationship of the nursing practice environment with the quality of care and patients’ safety in primary health care. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, E.; Lin, C.-F.; Gaspar, F.; Lucas, P. Translation and Validation of the Indicators of Quality Nursing Work Environments in the Portuguese Cultural Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, A.; Adamakidou, T. Construction and Validation of the Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale (QONCS). BMC Nurs. 2014, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwin, L.; Alster, K.; Rubin, K.M. Development and Testing of the Oncology Patients’ Perceptions of the Quality of Nursing Care Scale. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2003, 30, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burduli, E.; Smith, C.L.; Tham, P.; Shogan, M.; Johnson, R.K.; McPherson, S.M. Development and Application of a Primer and Reference Assessment Tool for Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: A Phase I Pilot Study. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2020, 17, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Sharour, L.; Al Sabei, S.; Al Harrasi, M.; Anwar, S.; Salameh, A.B. Translation and Validation of the Arabic Version of the Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale (QONCS): Psychometric Testing in Three Arabic Countries. J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 2021, 36, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.C. Satisfação Do Paciente Oncológico Sobre o Cuidado Do Enfermeiro: Adaptação Transcultural e Validação Do Instrumento Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale (QONCS). Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association WMA: Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Beaton, D.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, Adaptation and Validation of Instruments or Scales for Use in Cross-Cultural Health Care Research: A Clear and User-Friendly Guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.R.; Grove, S.K. Grove’s The Practice of Nursing Research: Appraisal, Synthesis, and Generation of Evidence, 9th ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Perneger, T.V.; Courvoisier, D.S.; Hudelson, P.M.; Gayet-Ageron, A. Sample Size for Pre-Tests of Questionnaires. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilelas, J. Investigação: O Processo de Construção Do Conhecimento, 3rd ed.; Edições Sílabo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cruchinho, P.; Teixeira, G.; Lucas, P.; Gaspar, F. Evaluating the Methodological Approaches of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the Bedside Handover Attitudes and Behaviours Questionnaire into Portuguese. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2023, 15, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoBiondo-Wood, G.; Haber, J. Nursing Research: Methods and Critical Appraisal for Evidence-Based Practice, 9th ed.; Elsevier: St Louis, MO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Fundamentos de Pesquisa Em Enfermagem: Avaliação de Evidências Para a Prática Da Enfermagem, 9th ed.; Artemed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kyngäs, H.; Mikkonen, K.; Kääriäinen, M. The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IBM®. SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021; Version 27. [Google Scholar]

- IBM®. SPSS® AMOS; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, F.; Guimarães, R. Métodos Estatísticos Para o Ensino e a Investigação Nas Ciências Da Saúde; Edições Sílabo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Globocan. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/620-portugal-fact-sheets.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Cavalcanti, N.S.; Sekine, L.; Manica, D.; Farenzena, M.; Saleh Neto, C.D.S.; Marostica, P.J.C.; Schweiger, C. Translation and Validation of the Drooling Impact Scale Questionnaire into Brazilian Portuguese. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 88, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, D. Applied Univariate, Bivariate, and Multivariate Statistics: Understanding Statistics for Social and Natural Scientists, with Applications in SPSS and R, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, S. Estatísticas Aplicada à Investigação Em Ciência Da Saúde: Um Guia Com o SPSS; Lusociência: Loures, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.M.; Shin, Y.S. The Relationships between Moral Distress and Quality of Nursing Care in Oncology Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 26, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, M.; Zamanzadeh, V.; Valizadeh, L.; Khajehgoodari, M. Assessment of Nurse–Patient Communication and Patient Satisfaction from Nursing Care. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Refaay, S.M.M.; Shalaby, P.D.M.H.; Shama, P.D.G.T. Effect of Psycho Educational Program about Control of Suicidal Ideation among Psychiatric Patients on Nursing Staff’s Knowledge and Practice. Int. J. Nurs. 2019, 6, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrow, A.B.; Kwok, G.; Sharma, R.K.; Fromer, N.; Sulmasy, D.P. Spiritual Needs and Perception of Quality of Care and Satisfaction with Care in Hematology/Medical Oncology Patients: A Multicultural Assessment. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 56–64.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southard, M.E. Spirituality: The Missing Link for Holistic Health Care. J. Holist. Nurs. 2020, 38, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.; Caldeira, S.; Nunes, E.; Vieira, M. A Commentary on Spiritual Leadership and Workplace Spirituality in Nursing Management. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 602–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskenniemi, J.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Puukka, P.; Suhonen, R. Respect and Its Associated Factors as Perceived by Older Patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 3848–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, B.; McCance, T.V. Development of a Framework for Person-Centred Nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 44.6 |

| Female | 55.4 |

| Area of Residence | |

| Urban | 75.7 |

| Rural | 24.3 |

| Age | |

| 21 to 28 | 5.5 |

| 29 to 36 | 5.5 |

| 37 to 44 | 8.4 |

| 45 to 52 | 16.3 |

| 53 to 60 | 21.8 |

| 61 to 68 | 18.3 |

| 69 to 76 | 14.9 |

| 77 to 84 | 6.9 |

| 85 to 92 | 2.5 |

| Diagnosis time (in months) | |

| <1 month | 16.8 |

| 1 to 2 months | 23.3 |

| >2 months | 59.9 |

| Type of cancer | |

| Breast | 22.8 |

| Prostate | 1.0 |

| Bladder | 1.5 |

| Head and neck | 31.7 |

| Lung | 4.0 |

| Skin (melanoma) | 5.4 |

| Soft tissue | 5.0 |

| Other | 28.7 |

| Duration of treatment (in days) | |

| 0 to 7 | 69.8 |

| 8 to 14 | 12.9 |

| 15 to 21 | 9.4 |

| 22 to 29 | 1.5 |

| >29 | 6.4 |

| Received care for the first time | |

| Yes | 28.7 |

| No | 71.3 |

| Received previous care at that hospital | |

| Yes | 64.4 |

| No | 35.6 |

| Education level | |

| Fourth year (primary education level) | 20.8 |

| Sixth year (basic education—second cycle level) | 9.9 |

| Ninth year (basic education—third cycle level) | 15.8 |

| Eleventh year | 2.5 |

| Twelfth year (secondary education level) | 23.8 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 3.0 |

| Licentiate degree | 17.3 |

| Other | 6.9 |

| Items | Being Supported, Validated, and Valued | Spiritual/ Religious Caring | Feeling Supported | Being Respected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.763 | |||

| 2 | 0.798 | |||

| 3 | 0.763 | |||

| 4 | 0.695 | |||

| 5 | 0.747 | |||

| 6 | 0.810 | |||

| 7 | 0.678 | |||

| 8 | 0.764 | |||

| 9 | 0.732 | |||

| 10 | 0.796 | |||

| 11 | 0.808 | |||

| 12 | 0.805 | |||

| 13 | 0.774 | |||

| 14 | 0.795 | |||

| 15 | 0.789 | |||

| 16 | 0.748 | |||

| 28 | 0.796 | |||

| 29 | 0.836 | |||

| 30 | 0.604 | |||

| 31 | 0.853 | |||

| 32 | 0.844 | |||

| 17 | 0.857 | |||

| 18 | 0.934 | |||

| 19 | 0.942 | |||

| 20 | 0.936 | |||

| 21 | 0.771 | |||

| 22 | 0.785 | |||

| 23 | 0.780 | |||

| 24 | 0.846 | |||

| 25 | 0.861 | |||

| 26 | 0.824 | |||

| 27 | 0.805 | |||

| 33 | 0.866 | |||

| 34 | 0.882 | |||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomes, P.; Ribeiro, S.; Silva, M.; Cruchinho, P.; Nunes, E.; Nascimento, C.; Lucas, P. Cross-Cultural Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale. Cancers 2024, 16, 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16050859

Gomes P, Ribeiro S, Silva M, Cruchinho P, Nunes E, Nascimento C, Lucas P. Cross-Cultural Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale. Cancers. 2024; 16(5):859. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16050859

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes, Pedro, Susana Ribeiro, Marcelle Silva, Paulo Cruchinho, Elisabete Nunes, Carla Nascimento, and Pedro Lucas. 2024. "Cross-Cultural Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale" Cancers 16, no. 5: 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16050859

APA StyleGomes, P., Ribeiro, S., Silva, M., Cruchinho, P., Nunes, E., Nascimento, C., & Lucas, P. (2024). Cross-Cultural Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Quality of Oncology Nursing Care Scale. Cancers, 16(5), 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16050859