Recommended Physiotherapy Modalities for Oncology Patients with Palliative Needs and Its Influence on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

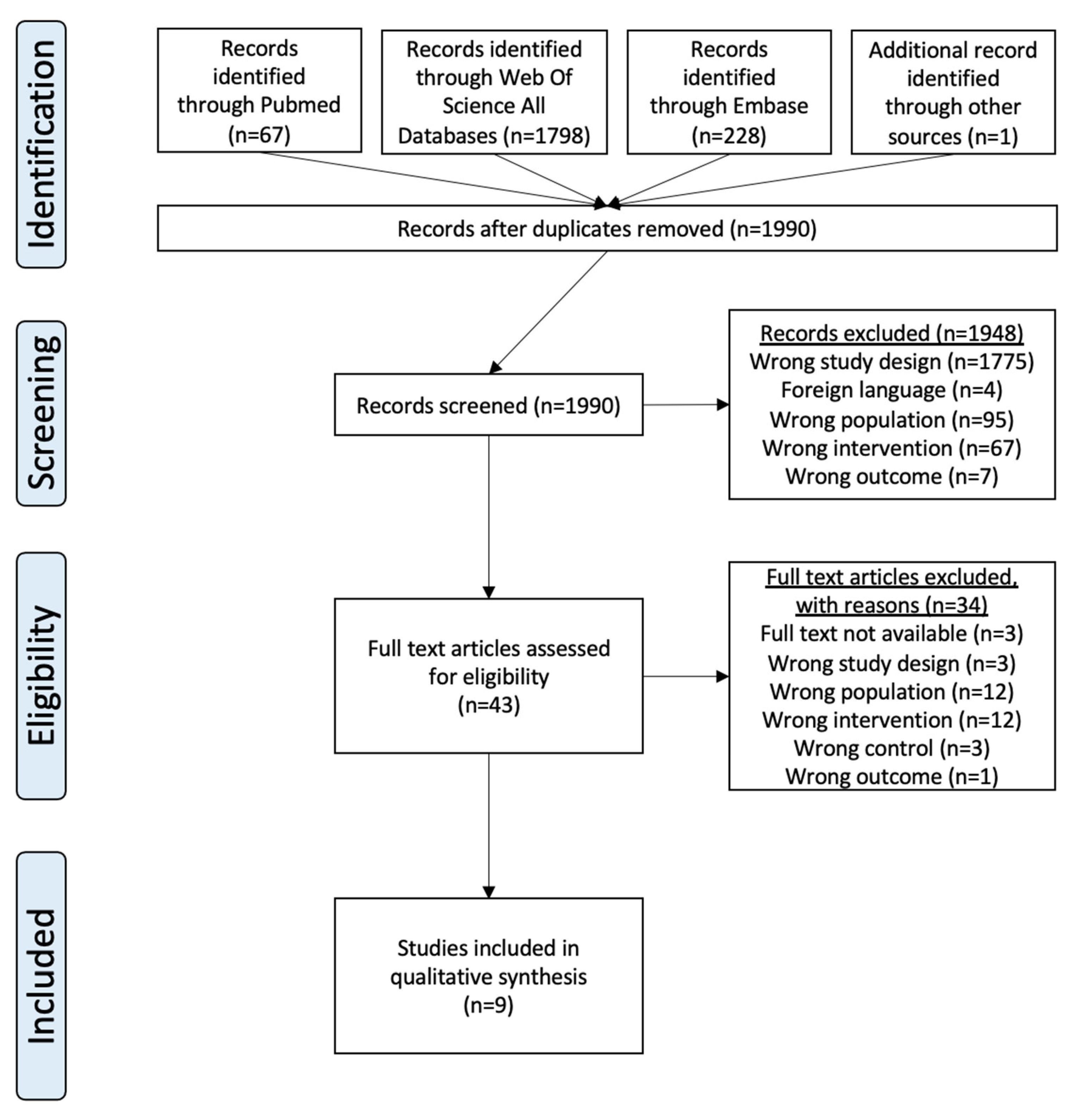

2.1. Study Selection Procedure

- Population: adults aged 18 and over with solid tumors, with more than 50% of the sample having palliative needs.

- Intervention: PT, including various modalities beyond just the term “physiotherapy” to capture a comprehensive range of interventions.

- Comparison: usual care (UC).

- Outcome: six patient-reported outcomes (PROMs): fatigue, quality of life (QoL), nutrition, pain, psychosocial functioning (PSF), and PHF.

2.2. Data Extraction

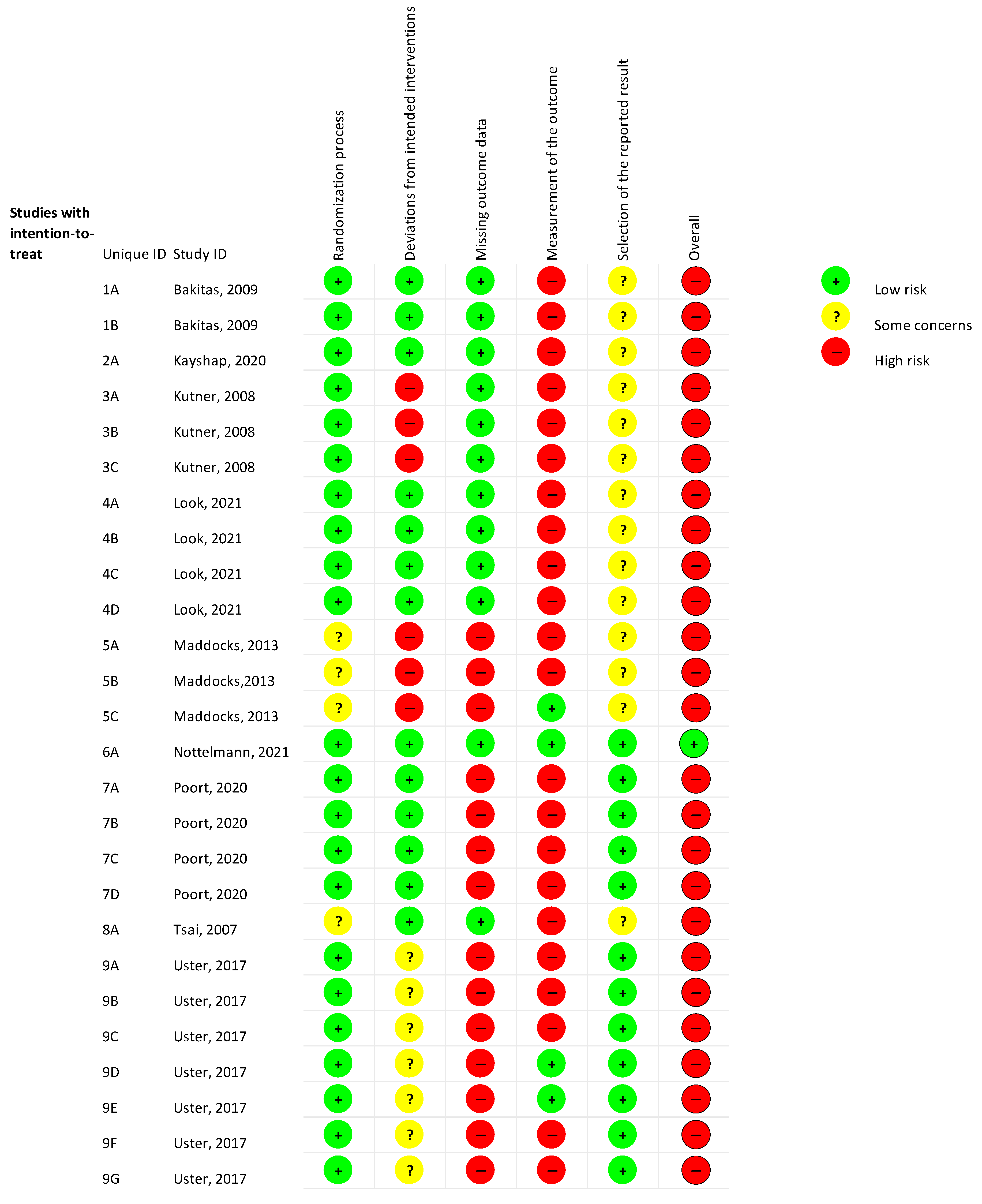

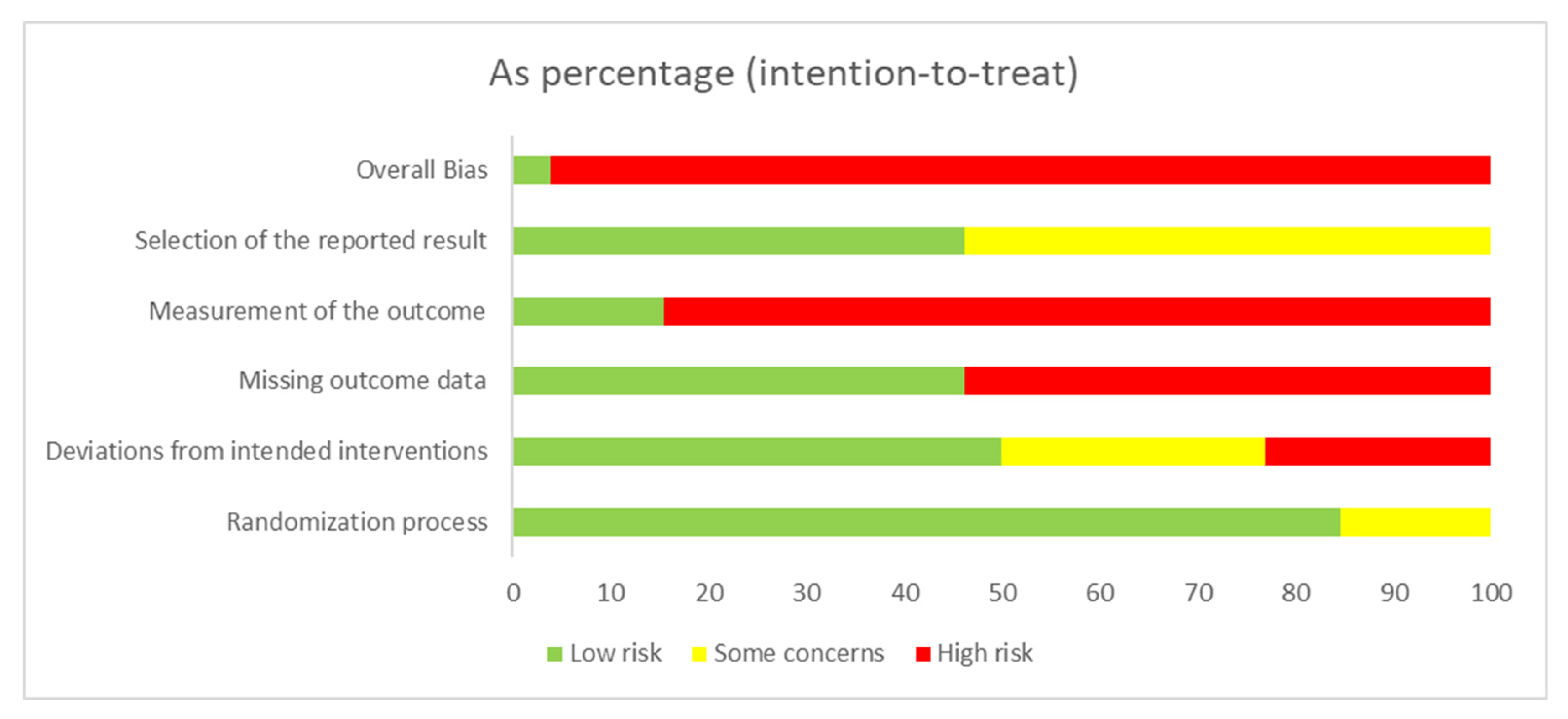

2.3. Assessment of Risk of Bias (RoB)

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Fatigue

3.3. QoL

3.4. Nutrition

3.5. PHF

3.6. PSF

3.7. Pain

3.8. GRADE

3.9. Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

4.2. Broader Context and Future Research

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Combination Terms | PubMed | Web of Science (All Databases) | EMBASE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | ((“Adult”[Mesh]) AND ((((“Neoplasms”[Mesh]) OR (“oncology patients”)) OR (“cancer”)) OR (“advanced cancer”))) AND (((((((((((“Palliative Care”[Mesh]) OR (“Palliative Medicine”[Mesh])) OR (“Hospice Care”[Mesh])) OR (“Terminal Care”[Mesh])) OR (“Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing”[Mesh])) OR (“Terminal Treatment”)) OR (“Palliative Treatment”)) OR (“Supportive Care”)) OR (“Palliative Needs”)) OR (“Early Palliative Care”)) OR (“Early Integrated Palliative Care”)) | 30,156 | 34,729 | 71,249 |

| I | ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((“Physical Therapy Modalities”[Mesh]) OR (“Physical Therapy Specialty”[Mesh])) OR (“Rehabilitation”[Mesh])) OR (“Drainage, Postural”[Mesh])) OR (“Electric Stimulation Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Hydrotherapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Mirror Movement Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Musculoskeletal Manipulations”[Mesh])) OR (“Myofunctional Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Massage”[Mesh])) OR (“Manual Lymphatic Drainage”[Mesh])) OR (“Myofascial Release Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Therapy, Soft Tissue”[Mesh])) OR (“Relaxation Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Autogenic Training”[Mesh])) OR (“Exercise”[Mesh])) OR (“Breathing Exercises”[Mesh])) OR (“Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation”[Mesh])) OR (“Patient Education as Topic”[Mesh])) OR (physiotherapy)) OR (“physiotherapist”)) OR (“exercise”)) OR (“exercise therapy”)) OR (“movement therapy”)) OR (“workout”)) OR (“cognitive behavioural therapy”)) OR (“cognitive behavioral therapy”)) OR (CBT)) OR (“manual therapy”)) OR (“comfort therapy”)) OR (“autogenic drainage”)) OR (“lymphatic drainage”)) OR (TENS)) OR (ESWT) | 1,067,802 | 3,260,090 | 1,784,970 |

| C | ((((((((((((((“Preferred Provider Organizations”[Mesh]) OR (“Oncology Nursing”[Mesh])) OR (“Usual Care”)) OR (“Usual Treatment”)) OR (“Usual Therapy”)) OR (“Standard Care”)) OR (“Standard Treatment”)) OR (“Standard Therapy”)) OR (“Conventional Care”)) OR (“Conventional Treatment”)) OR (“Conventional Therapy”)) OR (“Normal Care”)) OR (“Normal Treatment”)) OR (“Normal Therapy”)) OR (“Oncology Care”) | 126,239 | 2,986,819 | 192,281 |

| O | (((((((“Diet”[Mesh]) OR (“Diet”[Mesh])) OR (“Quality of Life”[Mesh])) OR (“Cachexia”[Mesh])) OR (“Pain”[Mesh])) OR (“Psychosocial Functioning”[Mesh])) OR (“Nutrition”)) OR (“Physical Functioning”) | 1,563,092 | 6,308,892 | 5,159,430 |

| P I C O | (((((“Adult”[Mesh]) AND ((((“Neoplasms”[Mesh]) OR (“oncology patients”)) OR (“cancer”)) OR (“advanced cancer”))) AND ((((((((((((“Palliative Care”[Mesh]) OR (“Palliative Medicine”[Mesh])) OR (“Hospice Care”[Mesh])) OR (“Terminal Care”[Mesh])) OR (“Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing”[Mesh])) OR (“terminal treatment”)) OR (“palliative treatment”)) OR (“supportive care”)) OR (“palliative needs”))) OR (“early palliative care”)) OR (“early integrated palliative care”))) AND (((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((“Physical Therapy Modalities”[Mesh]) OR (“Physical Therapy Specialty”[Mesh])) OR (“Rehabilitation”[Mesh])) OR (“Drainage, Postural”[Mesh])) OR (“Electric Stimulation Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Hydrotherapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Mirror Movement Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Musculoskeletal Manipulations”[Mesh])) OR (“Myofunctional Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Massage”[Mesh])) OR (“Manual Lymphatic Drainage”[Mesh])) OR (“Myofascial Release Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Therapy, Soft Tissue”[Mesh])) OR (“Relaxation Therapy”[Mesh])) OR (“Autogenic Training”[Mesh])) OR (“Exercise”[Mesh])) OR (“Breathing Exercises”[Mesh])) OR (“Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation”[Mesh])) OR (“Patient Education as Topic”[Mesh])) OR (physiotherapy)) OR (“physiotherapist”)) OR (“exercise”)) OR (“exercise therapy”)) OR (“movement therapy”)) OR (“workout”)) OR (“cognitive behavioural therapy”)) OR (“cognitive behavioral therapy”)) OR (CBT)) OR (“manual therapy”)) OR (“comfort therapy”)) OR (“autogenic drainage”)) OR (“lymphatic drainage”)) OR (TENS)) OR (ESWT))) AND (((((((((((((((“Preferred Provider Organizations”[Mesh]) OR (“Oncology Nursing”[Mesh])) OR (“usual care”)) OR (“usual treatment”)) OR (“usual therapy”)) OR (“standard care”)) OR (“standard treatment”)) OR (“standard therapy”)) OR (“normal care”)) OR (“normal treatment”)) OR (“normal therapy”)) OR (“conventional care”)) OR (“conventional treatment”)) OR (“conventional therapy”)) OR (“oncology care”))) AND ((((((((“Diet”[Mesh]) OR (“Diet”[Mesh])) OR (“Quality of Life”[Mesh])) OR (“Cachexia”[Mesh])) OR (“Pain”[Mesh])) OR (“Psychosocial Functioning”[Mesh])) OR (“nutrition”)) OR (“physical functioning”)) | 67 | 1798 | 228 |

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- World Health Organization. Cancer. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. 2024. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/en (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Ferlay, J.; Laversanne, M.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Tomorrow. 2024. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/tomorrow/en/dataviz/bars?multiple_populations=1&types=0&populations=900&years=2050&values_position=out (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Kom op tegen Kanker. Alles over Kanker. 2024. Available online: https://www.allesoverkanker.be (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Statbel. Doodsoorzaken. 2024. Available online: https://statbel.fgov.be/nl/themas/bevolking/sterfte-en-levensverwachting/doodsoorzaken#news (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Chowdhury, R.A.; Brennan, F.P.; Gardiner, M.D. Cancer Rehabilitation and Palliative Care-Exploring the Synergies. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy and the Association of Cesar and Mensendieck Exercise Therapists. KNGF Guideline on Oncology. Amersfoort. 2022. Available online: https://www.kennisplatformfysiotherapie.nl/richtlijnen/oncologie (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- National Cancer Institute. Palliative Care in Cancer. 2021. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/advanced-cancer/care-choices/palliative-care-fact-sheet (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Physiopedia Contributors. Physiotherapy in Palliative Care Physiopedia. 2023. Available online: https://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php?title=Physiotherapy_in_Palliative_Care&oldid=341655 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Gouldthorpe, C.; Power, J.; Taylor, A.; Davies, A. Specialist Palliative Care for Patients with Cancer: More Than End-of-Life Care. Cancers 2023, 15, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.P.; Jim, A. Physical therapy in palliative care: From symptom control to quality of life: A critical review. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2010, 16, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashleigh, L. Physiotherapy in palliative oncology. Aust. J. Physiother. 1996, 42, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vira, P.; Samuel, S.R.; Amaravadi, S.K.; Saxena, P.P.; Rai Pv, S.; Kurian, J.R.; Gururaj, R. Role of Physiotherapy in Hospice Care of Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021, 38, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgium FaH. End of Life Care. 2024. Available online: https://www.healthybelgium.be/en/health-system-performance-assessment/specific-domains/end-of-life (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- RIZIV. Palliatief Forfait n.d. Available online: https://www.riziv.fgov.be/nl/thema-s/verzorging-kosten-en-terugbetaling/wat-het-ziekenfonds-terugbetaalt/palliatieve-zorg/palliatief-forfait (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Howie, L.; Peppercorn, J. Early palliative care in cancer treatment: Rationale, evidence and clinical implications. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2013, 5, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.S.; Chen, P.L.; Lai, Y.L.; Lee, M.B.; Lin, C.C. Effects of electromyography biofeedback-assisted relaxation on pain in patients with advanced cancer in a palliative care unit. Cancer Nurs. 2007, 30, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutner, J.S.; Smith, M.C.; Corbin, L.; Hemphill, L.; Benton, K.; Mellis, B.K.; Beaty, B.; Felton, S.; Yamashita, T.E.; Bryant, L.L.; et al. Massage therapy versus simple touch to improve pain and mood in patients with advanced cancer: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 149, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakitas, M.; Lyons, K.D.; Hegel, M.T.; Balan, S.; Brokaw, F.C.; Seville, J.; Hull, J.G.; Li, Z.; Tosteson, T.D.; Byock, I.R.; et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, M.; Halliday, V.; Chauhan, A.; Taylor, V.; Nelson, A.; Sampson, C.; Byrne, A.; Griffiths, G.; Wilcock, A. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation of the quadriceps in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving palliative chemotherapy: A randomized phase II study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e86059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uster, A.; Ruehlin, M.; Mey, S.; Gisi, D.; Knols, R.; Imoberdorf, R.; Pless, M.; Ballmer, P.E. Effects of nutrition and physical exercise intervention in palliative cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, K.; Singh, V.; Mishra, S.; Dwivedi, S.N.; Bhatnagar, S. The Efficacy of Scrambler Therapy for the Management of Head, Neck and Thoracic Cancer Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Physician 2020, 23, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poort, H.; Peters, M.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Nieuwkerk, P.T.; van de Wouw, A.J.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G.; Bleijenberg, G.; Verhagen, C.; Knoop, H. Cognitive behavioral therapy or graded exercise therapy compared with usual care for severe fatigue in patients with advanced cancer during treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Look, M.L.; Tan, S.B.; Hong, L.L.; Ng, C.G.; Yee, H.A.; Lim, L.Y.; Ng, D.L.C.; Chai, C.S.; Loh, E.C.; Lam, C.L. Symptom reduction in palliative care from single session mindful breathing: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 11, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottelmann, L.; Groenvold, M.; Vejlgaard, T.B.; Petersen, M.A.; Jensen, L.H. Early, integrated palliative rehabilitation improves quality of life of patients with newly diagnosed advanced cancer: The Pal-Rehab randomized controlled trial. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali, M. Cancer-related fatigue: An overview. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30, S36–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, V.; Koshy, C. Fatigue in cancer: A review of literature. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2009, 15, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabi, A.; Bhargava, R.; Fatigoni, S.; Guglielmo, M.; Horneber, M.; Roila, F.; Weis, J.; Jordan, K.; Ripamonti, C.I.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cancer-related fatigue: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoli, D.; Schoo, C.; Kalish, V.B. Palliative Care; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Luta, X.; Ottino, B.; Hall, P.; Bowden, J.; Wee, B.; Droney, J.; Riley, J.; Marti, J. Evidence on the economic value of end-of-life and palliative care interventions: A narrative review of reviews. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, M.G.; George, A.; Vidyasagar, M.S.; Mathew, S.; Nayak, S.; Nayak, B.S.; Shashidhara, Y.N.; Kamath, A. Quality of Life among Cancer Patients. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2017, 23, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barajas Galindo, D.E.; Vidal-Casariego, A.; Calleja-Fernandez, A.; Hernandez-Moreno, A.; Pintor de la Maza, B.; Pedraza-Lorenzo, M.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.A.; Avila-Turcios, D.M.; Alejo-Ramos, M.; Villar-Taibo, R.; et al. Appetite disorders in cancer patients: Impact on nutritional status and quality of life. Appetite 2017, 114, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Haehling, S.; Anker, S.D. Prevalence, incidence and clinical impact of cachexia: Facts and numbers-update. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2014, 5, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roeland, E.J.; Bohlke, K.; Baracos, V.E.; Bruera, E.; Del Fabbro, E.; Dixon, S.; Fallon, M.; Herrstedt, J.; Lau, H.; Platek, M.; et al. Management of Cancer Cachexia: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2438–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Boocock, E.; Grande, A.J.; Maddocks, M. Exercise-based interventions for cancer cachexia: A systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 10 (Suppl. S1), 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, L.C.; Daun, J.T.; Ester, M.; Mosca, S.; Langelier, D.; Francis, G.J.; Chang, E.; Mina, D.S.; Fu, J.B.; Culos-Reed, S.N. Physical Activity for Individuals Living with Advanced Cancer: Evidence and Recommendations. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 37, 151170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhandiramge, J.; Orchard, S.G.; Warner, E.T.; van Londen, G.J.; Zalcberg, J.R. Functional Decline in the Cancer Patient: A Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, J.; Fukushima, T.; Tanaka, T.; Fu, J.B.; Morishita, S. Physical function predicts mortality in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5623–5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. Adjustment to Cancer: Anxiety and Distress (PDQ(R)): Patient Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries; PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. Cancer Pain (PDQ(R)): Health Professional Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries; PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. In The Psychosocial Needs of Cancer Patients; Adler, N.E., Page, A.E.K., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. Depression (PDQ(R)): Patient Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries; PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, M.; Giusti, R.; Aielli, F.; Hoskin, P.; Rolke, R.; Sharma, M.; Ripamonti, C.I.; Committee, E.G. Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29 (Suppl. S4), iv166–iv191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Chaturvedi, A. Complementary and alternative medicine in cancer pain management: A systematic review. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2015, 21, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanriverdi, A.; Ozcan Kahraman, B.; Ergin, G.; Karadibak, D.; Savci, S. Effect of exercise interventions in adults with cancer receiving palliative care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plinsinga, M.L.; Singh, B.; Rose, G.L.; Clifford, B.; Bailey, T.G.; Spence, R.R.; Turner, J.; Coppieters, M.W.; McCarthy, A.L.; Hayes, S.C. The Effect of Exercise on Pain in People with Cancer: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 1737–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, E.; Mayer-Steinacker, R.; Gencer, D.; Kessler, J.; Alt-Epping, B.; Schonsteiner, S.; Jager, H.; Coune, B.; Elster, L.; Keser, M.; et al. Feasibility, use and benefits of patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care units: A multicentre observational study. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer|Guidance: NICE. 2004. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg4 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

Population

| Population

|

Intervention

| Intervention

|

Comparison

| Comparison

|

Outcome

| Outcome

|

Study design

| Study design

|

Other

| Other

|

| Author, Year | Sample Size Total (Baseline) | Sample Size I (Baseline) | Sample Size C (Baseline) | Retention I (%) | Retention C (%) | Dropout Total (%) | Mean Age ± SD I | Mean Age ± SD C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsai et al. (2007) [19] | n = 37 | n = 20 | n = 17 | 60% | 70.59% | 35.14% | ≤40 (16.7)— 41–50 (58.3)— 51–60 (8.3)— ≥61 (16.7) | ≤40 (8.3)— 41–50 (25)— 51–60 (25)— ≥61 (41.7) |

| Kutner et al. (2008) [20] | n = 380 | n = 188 | n = 192 | 80.32% | 76.56% | 21.58% | 65.2 ± 14.4 | 64.2 ± 14.4 |

| Bakitas et al. (2009) [21] | n = 322 | n = 161 | n = 161 | 90.06% | 82.23% | 13.35% | 65.4 ± 10.3 | 65.2 ± 11.7 |

| Maddocks et al. (2013) [22] | n = 49 | n = 30 | n = 19 | 50% | 68.42% | 42.86% | 70 | 68 |

| Uster et al. (2017) [23] | n = 58 | n = 29 | n = 29 | 82.76% | 68.97% | 24.14% | 64.0 ± 11.0 | 62.0 ± 9.3 |

| Kashyap et al. (2020) [24] | n = 80 | n = 40 | n = 40 | 97.50% | 100% | 1.25% | 52 ± 9.98 | 47.4 ± 11.22 |

| Poort et al. (2020) [25] | n = 134 | CBTn = 46 & GETn = 42 | n = 46 | GET: 78.57% CBT: 84.78% | 86.96% | 16.42% | GET: 60.67 ± 10.75 CBT: 63.50 ± 8.15 | 63.93 ± 8.98 |

| Look et al. (2021) [26] | n = 40 | n = 20 | n = 20 | 100% | 100% | 0% | 66.75 ± 3.22 | 69.20 ± 2.54 |

| Nottelmann et al. (2021) [27] | n = 301 | n = 149 | n = 139 | 24.83% | 22.30% | 26.91% | 66 ± 9 | 66 ± 10 |

| Study (Author & Year) | Patient Population | Intervention | Components of the Intervention | Control | Outcomes | Traditional PC/EISPC | Type of PT Modality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsai et al. (2007) [19] | Adult patients with advanced cancer who scored 3 on the Brief Pain Inventory, KPS: 40–90 | EMG biofeedback-assisted relaxation (first 2 sessions visual display, last 4 sessions closed eyes) | 45′/sessions 3 × 3–7 min trials, 20% reduction in the EMG from pretraining level for 50% of the time in each trial, 6 sessions, 4 weeks | Usual care | PSF | Traditional PC | Relaxation Physical applications |

| Kutner et al. (2008) [20] | Advanced cancer adult patients with moderate pain, stages III-IV | Massage: gentle effleurage, petrissage, myofascial trigger point release | Session = 30′ effleurage (65% time), petrissage (35% time) & myofacial trigger point release (n = 3/session), up to 6 sessions with 24 h interval, 2 weeks | Control exposure: bilateral placement of hands, 3 min/location | QoL PSF Pain | Traditional PC | Massage |

| Bakitas et al. (2009) [21] | Patients with life-limiting cancer and new diagnosis within 8–12 w of GI tract, lung, genitourinary tract, breast cancer stage III or IV | Structured educational & problem-solving sessions (case-management, educational approach to encourage P activation, self-management and empowerment) + SMAs | Session 1: ±41′ Sessions 2–4: 30′ 4 sessions 1×/week | Usual care | QoL PSF | Traditional PC | Education |

| Maddocks et al. (2013) [22] | Adults with advanced (stage IV) NSCLC from thoracic oncology clinics scheduled to receive first line palliative chemotherapy | Neuromuscular electrical stimulation | Session = 30′ symmetrical biphasic squared pulses at 50 Hz, 350 microsec pulse width, duty cycle increasing on weekly basis from 11% to 18% to 25% and constant thereafter, daily (min 3×/week), 3 cycles chemo: 8 w 4 cycles chemo: 11 w | Usual care | Fatigue QoL PHF | Traditional PC | Physical applications |

| Uster et al. (2017) [23] | Patients with metastatic or locally advanced tumors of the gastrointestinal or the lung tracts + ECOG ≤ 2 | Nutrition and physical intervention (group 2–6 pers): warm-up, strength & balance training | Session = 60′ Strength: 60–80% 1RM in 2 sets of 10 reps → increase R Balance: 1′ → 2′, 2×/week, 3 months | Usual care | Fatigue QoL Nutrition PHF PSF | Traditional PC | Exercise |

| Kashyap et al. (2020) [24] | Head, neck & thoracic cancer patients with NRS-11 more than 4, stage II-IV | Scrambler therapy (electrodes according dermatome) | 40′ Scrambler therapy, intensity increased gradually, 5×/week, 2 weeks | Pain medication (WHO) + usual care | Pain | Traditional PC | Physical applications |

| Poort et al. (2020) [25] | Adult palliative cancer patients with severe cancer-related fatigue | CBT or GET (graded aerobic and resistance training) | CBT: 1 h sessions and GET: 2 h sessions, CBT: 10 individual sessions GET: 2×/week, 12 weeks | Usual care: guidelines by Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer organisation | Fatigue QoL PHF PSF | Traditional PC | CBT & GET (Education) (Exercise) |

| Look et al. (2021) [26] | Adult cancer patients with at least 5/10 on ESAS, ECOG I-IV | Mindful breathing exercise | 20′ in 4 steps (5′ per step), once, one session | Usual care | Fatigue Nutrition PSF Pain | Traditional PC | Breathing exercises |

| Nottelmann et al. (2021) [27] | Adult cancer patients receiving systemic medical treatment for metastatic or unresectable solid tumor (diagnosis <8 weeks) | 2 mandatory consults + educational sessions + exercise (aerobic + strength) | Education = 20′ + questions/debate and exercise = 60‘, 1×/week, 12 weeks | Usual care | QoL | EISPC | Education Exercise |

| PT versus Usual Care in Oncology Patients with Palliative Needs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population: Oncology Patients with Palliative Needs Intervention: PT Control: Usual Care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Absolute Effects * (95% CI) |

Relative Effect (95% CI) |

Number of Participants (studies) |

Certainty of the Evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Usual Care | Risk with PT | |||||

| Fatigue Questionnaires FU: range 4 weeks to 13 months | - | - | Improved ** | 281 (4 RCTs) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low a,b,c | A: ESAS, MFI-20, CSI-fatigue, EORTC-QLQ-C30 (v3.0) and SS PI: MBE, NMES, CBT, GET, nutritional counseling with a physical intervention S: Look et al. (2021) [26], Maddocks et al. (2013) [22], Poort et al. (2020) [25], and Uster et al. (2018) [23] |

| Quality of Life Questionnaires FU: range 1 week to 13 months | - | - | Improved ** | 1231 (6 RCTs) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low a,b,d | A: FACITPC, McGill QoL Questionnaire, EORTC QLQ-30, LC-13, SIP8, and functional scale PI: educational and problem-solving sessions, massage, NMES, educational sessions combined with PT sessions, CBT, GET, nutritional counseling with a physical intervention S: Bakitas et al. (2009) [21], Kutner et al. (2008) [20], Maddocks et al. (2013) [22], Nottelmann et al. (2021) [27], Poort et al. (2020) [25], and Uster et al. (2018) [23] |

| Nutrition (N1) Questionnaires FU: range 0 days to 3 months | - | - | Improved ** | 98 (2 RCTs) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low b,c,e | A: ESAS and three-day food diary PI: MBE and nutritional counseling with a physical intervention S: Look et al. (2021) [26] and Uster et al. (2018) [23] |

| Nutrition (N2) Objective measurements FU: 3 months | - | - | Contradiction between measurements | 58 (1 RCT) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low c,e | A: bioelectrical impedance analysis and weight scale PI: nutritional counseling with a physical intervention S: Uster et al. (2018) [23] |

| Physical functioning (PHF1) Questionnaires FU: range 4 weeks to 3 months | - | - | Improved ** | 192 (2 RCTs) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low a,b,c | A: EORTC-QLQ-C30 and functional scale PI: CBT, GET, and nutritional counseling with a physical intervention S: Poort et al. (2020) [25] and Uster et al. (2018) [23] |

| Physical functioning (PHF2) Objective measurements FU: range 0 days to 3 months | - | - | Contradiction between studies | 107 (2 RCTs) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low b,c,e | A: manual muscle tester dynamometer, handgrip strength, 6-min walk test, and timed sit-to-stand test PI: NMES and nutritional counseling with a physical intervention S: Maddocks et al. (2013) [22] and Uster et al. (2018) [23] |

| Psychosocial functioning Questionnaires FU: range 2 weeks to 13 months | - | - | Improved *** | 934 (5 RCTs) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low a,b,d | A: CES-D, MPAC mood scale, ESAS, EORTC-QLQ-C30 and functional scale PI: educational and problem-solving sessions, massage, MBE, CBT, GET, and nutritional counseling with a physical intervention S: Bakitas et al. (2009) [21], Kutner et al. (2008) [20], Look et al. (2021) [26], Poort et al. (2020) [25], and Uster et al. (2018) [23] |

| Pain Questionnaires FU: range 7 days to 13 months | - | - | Improved **** | 595 (5 RCTs) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low a,b,d | A: NRS-11, pain intensity scale of MPAC, BPI, ESAS, BPI-T, SS and EORTC-QLQ-C30 v3.0 PI: scrambler therapy, massage, MBE, electromyography biofeedback assisted relaxation, and nutritional counseling with a physical intervention S: Kashyap et al. (2020) [24], Kutner et al. (2008) [20], Look et al. (2021) [26], Tsai et al. (2007) [21], and Uster et al. (2018) [23] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gauchez, L.; Boyle, S.L.L.; Eekman, S.S.; Harnie, S.; Decoster, L.; Van Ginderdeuren, F.; De Nys, L.; Adriaenssens, N. Recommended Physiotherapy Modalities for Oncology Patients with Palliative Needs and Its Influence on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 3371. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193371

Gauchez L, Boyle SLL, Eekman SS, Harnie S, Decoster L, Van Ginderdeuren F, De Nys L, Adriaenssens N. Recommended Physiotherapy Modalities for Oncology Patients with Palliative Needs and Its Influence on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2024; 16(19):3371. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193371

Chicago/Turabian StyleGauchez, Luna, Shannon Lauryn L. Boyle, Shinfu Selena Eekman, Sarah Harnie, Lore Decoster, Filip Van Ginderdeuren, Len De Nys, and Nele Adriaenssens. 2024. "Recommended Physiotherapy Modalities for Oncology Patients with Palliative Needs and Its Influence on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review" Cancers 16, no. 19: 3371. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193371

APA StyleGauchez, L., Boyle, S. L. L., Eekman, S. S., Harnie, S., Decoster, L., Van Ginderdeuren, F., De Nys, L., & Adriaenssens, N. (2024). Recommended Physiotherapy Modalities for Oncology Patients with Palliative Needs and Its Influence on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Systematic Review. Cancers, 16(19), 3371. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193371