Simple Summary

Improved outcomes have been reported with adjuvant treatment combining cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors with endocrine therapy, in high-risk patients with ER-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer, regardless of age. In this real-world data analysis, MonarchE and NataLEE high-risk patients accounted for 9.5% and 33% of patients undergoing upfront surgery, respectively. Significantly higher eligibility rates were observed in patients who underwent a mastectomy, >70 years and ≤40 years for adjuvant abemaciclib and ribociclib, and in patients >80 years for ribociclib. A higher discontinuation rate for abemaciclib was reported in patients ≥65 years and it can be assumed that discontinuation rates may increase with more older patients. If the results of the NataLEE trial translate into clinical practice, the number of patients potentially eligible for adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitors may increase, especially in the elderly population.

Abstract

Background: Despite early diagnosis, approximately 20% of patients with ER-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer (BC) will experience disease recurrence. Improved survival has been reported with adjuvant treatment combining cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors with endocrine therapy, in high-risk patients with ER-positive and HER2-negative BC, regardless of age. Older patients have higher rates of ER-positive/HER2-negative BC than younger patients. Methods: In this real-world data analysis, MonarchE and NataLEE high-risk patients accounted for 9.5% and 33% of patients undergoing upfront surgery, respectively. Significantly higher eligibility rates were observed in patients who underwent a mastectomy, >70 years and ≤40 years for adjuvant abemaciclib and ribociclib, and in patients >80 years for ribociclib. Results: Eligibility rates in patients ≤40 years and >80 years who underwent mastectomy were 27.8% and 24.7% for abemaciclib, respectively, and 56.6% and 65.2% for ribociclib, respectively. A higher discontinuation rate for abemaciclib was reported in patients aged ≥65 years and it can be assumed that discontinuation rates may increase in even older patients. Conclusions: If the results of the NataLEE trial translate into clinical practice, the number of patients potentially eligible for adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitors may increase, especially in the elderly population.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer death in women. The incidence of BC increases with age and more than 30% of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer are aged 65 years or older [1], and approximately 24.8% of patients are aged 70 years or older [1,2]. Between 1990 and 2023, the annual number of new cases of BC in women in France has doubled from 29,934 to 61,214 cases per year [3]. Half of this increase is due to population growth and aging. Age-specific trends show an average increase in BC of about +1% per year for all age groups, except for women in their 70s, for whom the increase is higher (+1.9%) [4].

The decline in BC mortality is the result of major therapeutic advances combined with an increase in the proportion of cancers diagnosed at an early stage, particularly through organized screening. However, this mortality benefit appears to be less evident in older patients and 60% of BC deaths occur in women aged 65 years and older [4].

Approximately 80% of BC have an ER-positive HER2-negative phenotype [2]. Elderly patients presenting with more advanced BC, partly due to the lack of systemic screening [5,6], have higher rates of ER-positive/HER2-negative phenotypes than younger cohorts, such as those included in pivotal studies [7], with higher rates of triple-negative (TN) BC and HER2-positive BC in young (≤40 years old) and very young (≤35 years old) patients [8]. Similarly, a recent study of 235,368 patients with early BC reported an increase in Luminal BC with increasing age: 46.9% in those aged <30 years; 87% in those aged 70–79 years; and 93.4% in patients aged 80 years or older [2].

In the large French cohort study reported by Dumas et al. [2], mastectomy rates for upfront surgery or after neoadjuvant chemotherapy were 41.2% in patients <40 years (4802/11,663), 24.8% in patients 70–79 years (9694/39,163), 43.4% in patients ≥ 80 years (8366/19,291), and 23.8% in patients 40–69 years (39,333/165,251). The mastectomy rate was 25.7% (39,362/153,379) in Luminal BC. Elderly BC patients are often undertreated compared to younger BC patients [9,10,11,12] and have higher rates of recurrence and mortality [10,13,14,15,16,17], with a 5-year survival rate of 82.4% in patients aged 70–79 years and 74% in patients over 80 years [13,17,18,19]. It should be noted that non-compliance with endocrine therapy and radiotherapy is higher in patients aged 80 years and over [16,20,21,22,23,24,25].

In addition, despite early diagnosis, around 20% of patients with ER-positive and HER2-negative BC experience disease recurrence within the first decade, and this persistent risk highlights the need for novel therapeutic strategies, particularly for those with high-risk disease [26]. The risk of distant recurrence was strongly correlated with initial TN status, with risks ranging from 10 to 41%, depending on TN status and tumor grade [27]. For patients with T1N0 BC, the risk of distant recurrence was 10% for grade 1 BC, 13% for grade 2, and 17% for grade 3, 20% for T1N1 with 1–3 nodes involved, 34% for T1N2 with 4–9 nodes involved, 19% for T2N0, 26% for T2N1 with 1–3 nodes involved, and 41% for T2N2 with 4–9 nodes involved. These probabilities are only slightly reduced by the risk of death from another cause, except for women aged over 70 or in poor health.

In high-risk patients, adjuvant abemaciclib in the MonarchE trial [28] and ribociclib in the NataLEE trial [29] showed significantly improved survival with a combination of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i: ribociclib and abemaciclib) and endocrine therapy (ET) compared to patients receiving ET alone. The side effects of abemaciclib or ribociclib and ET are likely to be a significant limitation to compliance with these treatments over prolonged periods (3 years, 2 years, and 10 years, respectively), which could vary significantly depending on the age of the patients. In the MonarchE trial with adjuvant abemaciclib, most common adverse events (AEs) including diarrhea occurred early during treatment and were often low grade (diarrhea grade 1–2: 75.7% vs. 8.5%; grade ≥ 3: 7.8% vs. 0.2%, for abemaciclib + ET vs. ET alone, respectively). Management of these side effects led to 43% of patients requiring at least one dose reduction [28]. Dose reductions enabled treatment to be maintained in most cases, and the analyses did not reveal any negative impact on treatment efficacy [28]. Furthermore, during the treatment period, in both arms of the study, most patients reported being bothered “not at all” or “a little” by side effects [30]. More patients ≥65 years reported no diarrhea compared to younger patients (40% vs. 32%) at month 3 and the relative difference remained constant throughout the treatment period [30]. Overall and clinically relevant AE rates in patients treated with abemaciclib were similar between patients <65 years and older patients (49% vs. 54%), including grade 3 AEs [30]. However, dose reductions and treatment discontinuations due to AEs were more frequent in patients ≥65 years than in patients <65 years (dose reduction: 55% vs. 42%; treatment discontinuation: 38% vs. 15%) [30], and in each subgroup patients stopped treatment without prior dose adjustment (19% in patients ≥ 65 years versus 8% in patients <65 years) [30]. Finally, the long-term PRO data for MonarchE suggest that the toxicities of abemaciclib, including diarrhea, have no impact on patients’ overall quality of life when well managed. In the NataLEE trial, the initial dose of 400 mg was thought to improve the tolerability of ribociclib, but the safety profile was similar to conventional 600 mg dosing, and the discontinuation rate due to an adverse event was high (19% in the ribociclib arm vs. 4% in the placebo arm) [29].

Our study aimed to evaluate eligibility rates of adjuvant abemaciclib or ribociclib and ET among early BC patients who underwent upfront surgery, for all patients and according to age subgroups and breast conservative surgery (BCS; lumpectomy) or mastectomy.

2. Materials and Methods

From a large multicenter cohort (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT03461172), 17,097 ER-positive and HER2-negative early BC patients who underwent upfront surgery in 13 French centers between 1990 and 2023 were retrospectively selected. HR positivity was determined according to the French guidelines (estrogen and/or progesterone receptors by IHC with a 10% threshold for HR positivity).

The main recorded characteristics were age (≤40 years, 41–50, 51–74, and ≥75), tumor histology (ductal, lobular, mixt, or other), SBR grade 1 or 2, sentinel node (SN) status (pN0 or pN0(i+) or micrometastases or macrometastases), pT size (pT1, pT2 ≤ 30 mm, or pT2 > 30 mm), lymphovascular invasion (LVI), breast surgery (BCS or mastectomy), axillary surgery (sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) or SLNB and completion axillary lymph node dissection (cALND) or ALND alone), Ki 67 (>20 or ≤20), adjuvant chemotherapy (AC), and post-mastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT). The R0/R1 status was not present in the data collection, but patients with conservative treatment and positive bank were all re-operated on, either by conservative retreatment or mastectomy (which was then the final procedure retained in the data)

Patients eligible for abemaciclib in the MonarchE trial [31] included pT3 and/or pT1–2 grade 3 with 1–3 pathological axillary lymph nodes, and pT1–2 grade 1–2 with ≥4 pathological axillary lymph nodes. In the NataLEE trial [32], the inclusion criteria were broader and included patients with stage II, N0, grade 2, and Ki 67 ≥ 20% or determined to be high-risk according to prognostic gene-expression signatures.

We determined eligibility for adjuvant abemaciclib and ribociclib for all patients and according to age <70 years or ≥70 years old, 70–74 years or 75–80 years or >80 years old, ≤40 years or 41–50 years old, and upfront BCS or mastectomy, in univariate analysis. Treatments received were analyzed in a regression analysis according to age <70 years or ≥70 years old, and 70–74 years or 75–80 years or >80 years old. Eligibility rates for adjuvant abemaciclib or ribociclib were then analyzed according to age, type of surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) or not.

Statistics: Standard descriptive statistics were used to describe patient and tumor characteristics. All statistical tests were two-sided. The level of statistical significance was set at a p-value ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

Population: Median age was 60 years (mean 59.9) for all patients: 40.2% (6338/17,097) ≥65 years. Characteristics of 17,097 ER-positive and HER2-negative early BC patients who underwent upfront surgery for all patients, for patients <70 years or ≥70 years old, 70–74 years or 75–80 years or >80 years old, ≤40 years or 41–50 years old, and for breast lumpectomy or mastectomy are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. All factors were significantly different between age subgroups, except tumor histology according to age 70–74 years or 75–80 years or >80 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 17,097 ER-positive and HER2-negative early BC patients who underwent upfront surgery for all patients, for patients <70 years or ≥70 years old, and breast lumpectomy or mastectomy.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 17,097 ER-positive and HER2-negative early BC patients who underwent upfront surgery according to age category.

Treatments administered according to age ≥70 years or <70 years old, and 70–74 or 75–80 or >80 years old, in regression analysis adjusted for pT size, SBR grade, histology, LN status, LVI, and type of breast surgery are shown in Table 3. Less AC, ALND, PMRT, and more mastectomies were observed in patients ≥70 years compared to <70 years and in patients >80 years compared to 70–74 years.

Table 3.

Treatments administered according to age ≥70 years or <70 years old, and 70–74 or 75–80 or >80 years old, in regression analysis adjusted on pT size, SBR grade, histology, LN status, LVI, and type of breast surgery.

3.1. Eligibility for Adjuvant Abemaciclib or Ribociclib in All Patients

The overall eligibility rate for adjuvant abemaciclib was 9.46% (1617/17,097) and 32.91% (5627/17,097) for adjuvant ribociclib. The median age was 58 years (mean 58.3) in patients eligible for abemaciclib and 60 years (mean 60.1) in patients ineligible for abemaciclib, and 58.5 years (mean 58.9) and 61 years (mean 60.4) in patients eligible and ineligible for ribociclib, respectively. Patients were aged <65 years in 66.8% (1080/1617) of patients eligible for abemaciclib and 65.9% (3710/5627) of patients eligible for ribociclib. The number of patients eligible for adjuvant abemaciclib or ribociclib by pT size, pN status, and SBR grade is shown in Table 4. In addition, 17.0% of patients with pT3 BC were grade 3: 20.8% (97/466) of pT3pN1 with macrometastases, 12.5% (36/287) of pT3pN0 or pN0(i+), and 8.5% (5/59) of pT3pN1mi.

Table 4.

Number of patients eligible for adjuvant abemaciclib or ribociclib according to pT size, pN status, SBR grade, and ≥4 pN+ rates.

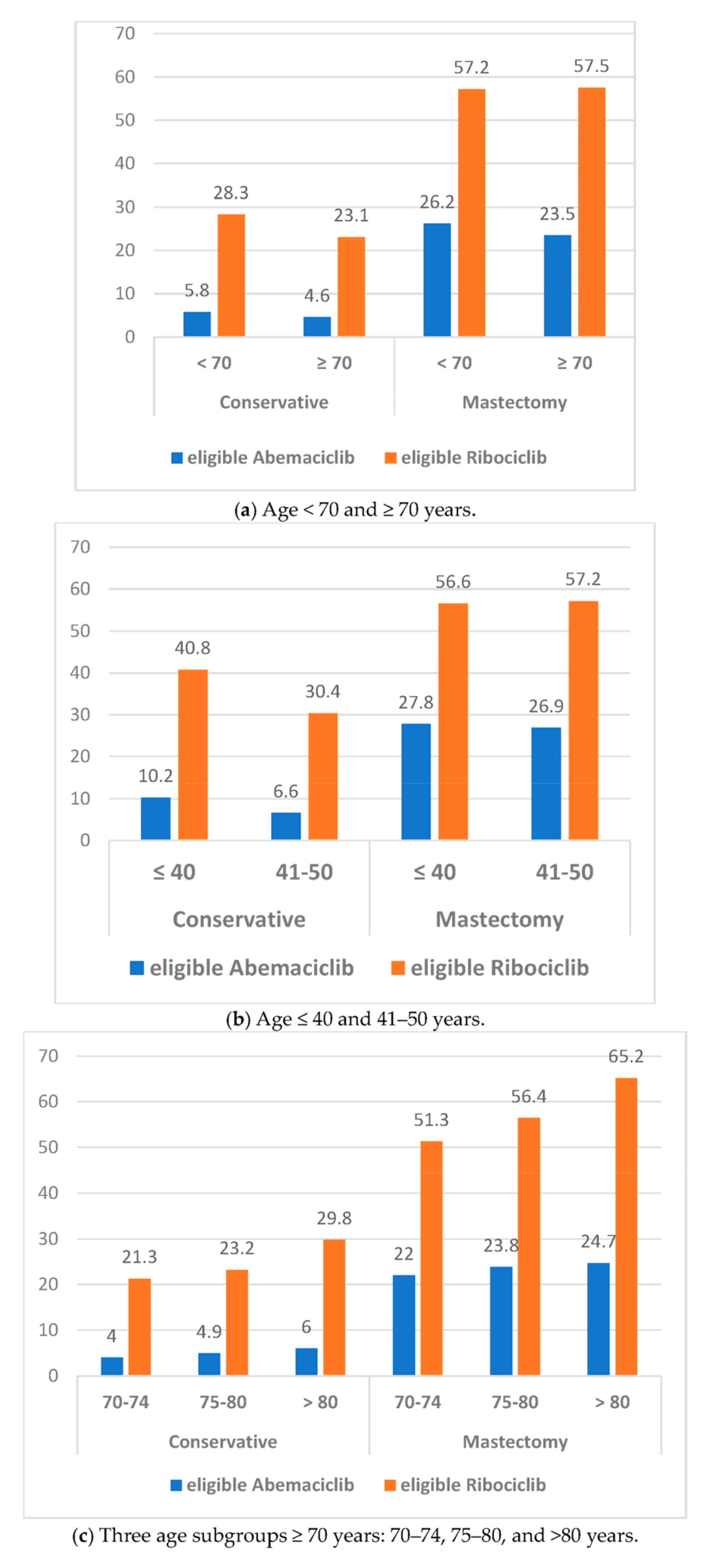

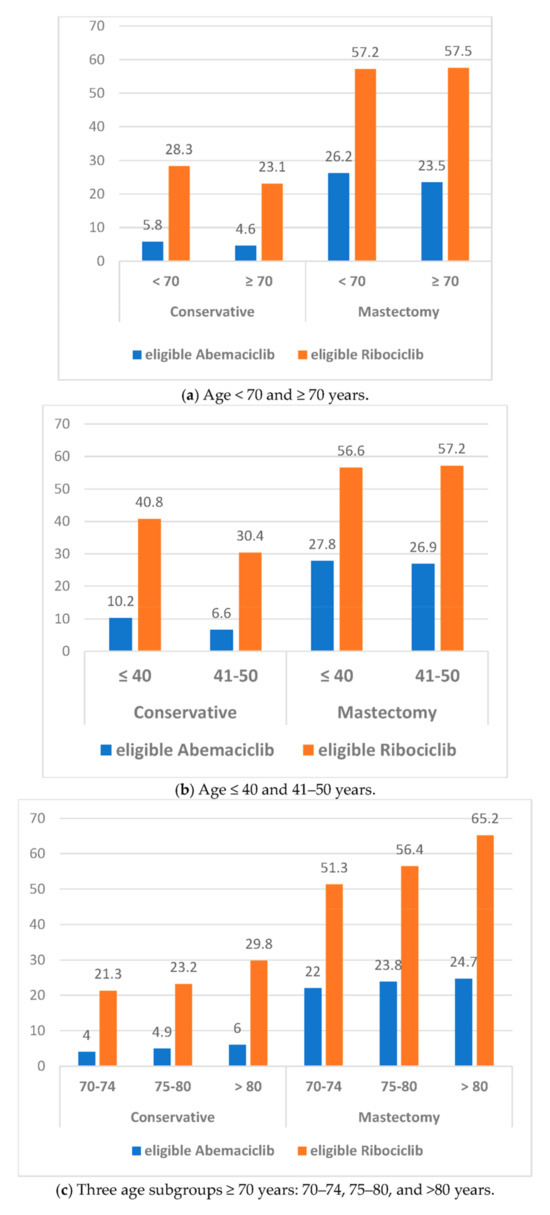

3.2. Eligibility for Adjuvant Abemaciclib or Ribociclib According to Age and Breast Surgery (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Eligibility rates for abemaciclib and ribociclib according to age subgroups and breast lumpectomy or mastectomy.

Eligibility rates according to age subgroups <70 years or ≥70 years, 70–74 years or 75–80 years or >80 years, ≤40 years or 41–50 years, and by BCS or mastectomy are shown in Table 5. Eligibility rates for abemaciclib and ribociclib were significantly higher in patients aged <70 years, higher in patients aged >80 years and 75–80 years compared to 70–74 years, higher in patients aged ≤40 years compared to 41–50 years, and higher for mastectomy compared to BCS.

Table 5.

Eligibility rates according to age subgroups <70 years or ≥70 years old, 70–74 years or 75–80 years or >80 years old, ≤40 years or 41–50 years old, and according to breast lumpectomy or mastectomy.

We then determined the eligibility rates according to the combination of age and breast surgery (Table 5). Significant lower rates were observed for patients who underwent BCS, ≥70 years vs. >70 years, and 41–50 years vs. ≤40 years for adjuvant abemaciclib and ribociclib, and patients 70–74 years versus 75–80 and >80 years for ribociclib only. In patients who underwent a mastectomy, a significantly higher rate was only observed in patients >80 years compared to 70–74 years and 75–80 years.

Higher rates of adjuvant abemaciclib and ribociclib were reported in patients with AC versus without AC, and in patients who underwent mastectomy versus BCS among patients with AC and patients without AC.

Eligibility rates by combination of age and with or without adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 5). In patients without AC, higher rates were observed in patients ≥70 years versus <70 years, in elderly patients (>80 years versus 75–80 and 70–74 years) for abemaciclib and ribociclib, and in younger patients (≤40 years versus 41–50) for abemaciclib alone. Similar results were observed in patients with AC for patients ≥70 years versus <70 years, for elderly patients (>80 years versus 75–80 and 70–74 years) for abemaciclib, and only for patients ≥70 years versus <70 years for ribociclib. In younger patients with AC, lower rates were observed with ribociclib.

3.3. Regression Analysis for Adjuvant Abemaciclib and Ribociclib Adjusted for Age and BCS or Mastectomy for All Patients and according to Patients Treated with or without AC (Table 6)

Table 6.

Regression analysis for adjuvant abemaciclib and ribocilib adjusted on age and BCS or mastectomy for all patients and according to patients treated with or without AC.

In all subgroups analyzed, mastectomy versus BCS was significantly associated with higher eligibility for abemaciclib and ribociclib. Among patients ≥70 years, older patients (>80 years) were associated with higher eligibility for abemaciclib regardless of AC or no AC, and for ribociclib in patients without AC. For patients with AC that selected larger pT sizes, more pN1, and grade 3 BC, there was no significant association with age ≤40 years and 41–50 years with the eligibility rate for abemaciclib.

4. Discussion

The overall eligibility rate was 9.46% for adjuvant abemaciclib and 32.91% for adjuvant ribociclib. Higher rates were observed for patients <70 years old versus ≥70 years, but with higher rates for patients >80 years versus 70–74 and 75–80 years, and for patients ≤40 years versus >40 years, and significantly higher for mastectomy versus BCS.

High-risk patients: High-risk patients had distant recurrence rates of 20% for T1N1 with 1–3 nodes involved, 34% for T1N2 with 4–9 nodes involved, 19% for T2N0, 26% for T2N1 with 1–3 nodes involved, and 41% for T2N2 with 4–9 nodes involved [27]. Adjuvant abemaciclib in the MonarchE trial [31] and ribociclib in the NataLEE trial [29,32] showed significantly improved outcomes with the combination of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors and ET compared to patients receiving ET alone. However, dose reductions and treatment discontinuations due to AEs were common with both treatments.

Eligibility: A previous retrospective US study using the MonarchE combined clinicopathological classification [33] reported a higher rate with 14% (557/4028) of patients considered MonarchE high risk. Similarly, a 2010–2015 SEER registry analysis [34] reported that 12% (28,619/238,222) of the patients were considered as archE high-risk. We found more pN1 (1–3 involved nodes) at 56.4% (912/1617) and less pN2 (≥involved nodes) at 43.6% compared to the MonarchE population with 40% and 60% of pN1 and pN2, respectively. The distribution for adjuvant ribociclib in our cohort was 12.5% of pN2 (705/5627), 78% of pN1 (4388/5627), and 9.5% of pN0 (534/5627) compared to 28% of patients classified as N0 based on baseline characteristics in the NataLEE trial. In the SEER registry analysis [34], this distribution differs with 47% of patients with N1 and 53% with N2–3 BC. In our cohort, patients eligible for abemaciclib were more likely to have pT3 BC (32.5%: 525/1617) than in the MonarchE trial (21.9%: 1217/5556), and 14.4% (812/5627) of patients eligible for ribociclib in our cohort had pT3 BC. In our cohort, 11.3% of BC were grade 3 (1937/17,097): 42.3% of patients were eligible for abemaciclib (819/1937) compared to 40.0% (2150/5370) in the MonarchE trial and 65.3% of patients were eligible for ribociclib (1264/1937) in our cohort. In addition, the mean age was higher in our cohort in patients eligible for abemaciclib (58 vs. 51 years in MonarchE) and in patients eligible for ribociclib (58.9 vs. 52 years in NataLEE). We found a higher proportion of patients aged ≥65 years eligible for abemaciclib (33.2%: 537/1617) than in the MonarchE trial (15.08%: 850/5637) and 34.1% (1917/5627) of patients eligible for ribociclib in our cohort were aged ≥65 years. Although the age of 65 years was chosen in the MonarchE trial, we analyzed the results both in patients considered old (≥70 years) and very old (>80 years), and in young or premenopausal (<50 years) and very young (≤40 years) patients.

Mastectomy and age: Higher mastectomy rates were reported in patients <40 years (41.2%) and in patients ≥80 years (43.4%) compared to the age subgroups 40–69 years (23.8%) and 70–79 years (24.8%) for upfront surgery or after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for all tumor subtypes [2]. Similarly, for ER-positive and HER2-negative BC, we observed higher mastectomy rates in older patients (39.4%, 23.7%, and 15.6% for patients aged >80 years, 75–80 years, and 70–74 years, respectively), and in younger patients (35.3% and 24.8% for patients aged ≤40 years and 41–50 years, respectively), with significant differences in multivariate analysis (Table 3). These rates may be due to patient preference and/or more advanced BC in older patients.

In addition, ER-positive and HER2-negative BC are more common in elderly patients [2,7]. As a result, a higher proportion of elderly patients may be eligible for adjuvant abemaciclib or ribociclib, and dose reductions and discontinuations due to AEs may increase in these patients. Tolaney et al. [30] reported a higher rate of abemaciclib discontinuation in patients aged ≥65 years and it can be assumed that discontinuation rates may increase with older patients. Unfortunately, the lower dose of ribociclib in the adjuvant setting (400 mg) did not show an improved tolerance profile compared with the metastatic setting (600 mg). This might represent a concern regarding observance and continuation in older patients with a high eligibility rate (30.6% and 43.5% in patients aged 75–80 years and >80 years, respectively) if ribociclib becomes available in clinical practice according to the NataLEE trial.

Prognostic gene-expression signatures are used to identify high-risk patients for the indication of AC but may not be sufficient to identify high-risk patients eligible for abemaciclib or ribociclib. Indeed, the NataLEE trial used a high genomic risk signature to assess eligibility for pT2 pN0 grade 2 breast cancer (BC) patients. However, only 17 patients met these criteria, resulting in a limited ability to draw meaningful conclusions from this aspect of the trial [29].

Our study has certain limitations. As a retrospective analysis, this study inherently suffers from selection bias and limitations in data availability. Moreover, the following limitations are also noted: the long time frame of inclusions with significant advancements having been made in treatment protocols; the study of age subgroups without specification of menopausal status; the lack of an onco-geriatric assessment; and the lack of gene-expression signatures that could have provided additional information on a minority population in the NataLEE trial. HER2-low status was not reported. While prognostic differences between HER2-low status and HER2 IHC 0 breast cancers have been reported, most studies found small or no differences in prognosis after adjusting for HR status [35,36,37], including in CDK4/6i-treated patients [38,39]. We also acknowledge the broader context of evolving breast cancer treatments and the future direction of personalized medicine [40].

5. Conclusions

Although ER-positive and HER2-negative BC is known to carry the better prognosis among BC subtypes, high-risk patients have a significantly increased risk of recurrence. This real-world data analysis, based on a large multicenter cohort, identifies up to 9.5% and 33% of high-risk patients according to MonarchE and NataLEE, respectively. Significantly higher eligibility rates were observed in patients who underwent a mastectomy, >70 years, ≤40 years for adjuvant abemaciclib and ribociclib, and in patients >80 years for ribociclib.

These clinical factors identified in the present work underline the need for physicians to be particularly aware of the case of elderly subjects, given the higher rate of CDK4/6i discontinuation reported in patients ≥65 years of age. Specific observational studies in older patients with detailed analysis of geriatric assessment, tolerability, and outcomes in these patients, especially those over 70 or 80 years, are warranted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.H.; methodology: G.H.; formal analysis: G.H. and A.d.N.; validation: G.H., M.C. and A.d.N.; investigation: G.H. and A.d.N.; data curation: G.H., M.C., J.-M.C., P.G., E.J., F.R., M.-P.C., C.M., P.-E.C., C.F.-V., C.B., R.R., C.C., A.-S.A., E.D. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation: G.H., M.C. and A.d.N.; writing—review and editing: G.H., M.C. and A.d.N.; supervision: G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Paoli Calmettes Institute under the reference CDD-G3S on April 2006.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to this being a retrospective study with all criteria recorded for clinical practice.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found in the Paoli Calmettes Institute breast cancer database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, E.; Laot, L.; Coussy, F.; Grandal Rejo, B.; Daoud, E.; Laas, E.; Kassara, A.; Majdling, A.; Kabirian, R.; Jochum, F.; et al. The French Early Breast Cancer Cohort (FRESH): A Resource for Breast Cancer Research and Evaluations of Oncology Practices Based on the French National Healthcare System Database (SNDS). Cancers 2022, 14, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panorama des Cancers en France, l’Institut National du Cancer Publie L’édition 2023 Rassemblant les Données les Plus Récentes—Dossiers et Communiqués de Presse n.d. Available online: https://www.e-cancer.fr/Presse/Dossiers-et-communiques-de-presse/Panorama-des-cancers-en-France-l-Institut-national-du-cancer-publie-l-edition-2023-rassemblant-les-donnees-les-plus-recentes (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Defossez, G.; Le Guyader-Peyrou, S.; Uhry, Z.; Grosclaude, P.; Colonna, M.; Dantony, E.; Delafosse, P.; Molinié, F.; Woronoff, S.; Bouvier, M.; et al. Estimations Nationales de L’incidence et de la Mortalité par Cancer en France Métropolitaine Entre 1990 et 2018; Synthèse St-Maurice Santé Publique Fr: Saint-Maurice, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lodi, M.; Scheer, L.; Reix, N.; Heitz, D.; Carin, A.-J.; Thiébaut, N.; Neuberger, K.; Tomasetto, C.; Mathelin, C. Breast cancer in elderly women and altered clinico-pathological characteristics: A systemic review. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 166, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenberg, Y.; Naeim, A.; Uziely, B.; Peretz, T.; Jacobs, J.M. Breast cancer among older women: The influence of age and cancer stage on survival. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 76, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvold, N.D.; Taghian, A.G.; Niemierko, A.; Abi Raad, R.F.; Sreedhara, M.; Nguyen, P.L.; Bellon, J.R.; Wong, J.S.; Smith, B.L.; Harris, J.R. Age, Breast Cancer Subtype Approximation, and Local Recurrence After Breast-Conserving Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3885–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, O.; Houvenaeghel, G.; Classe, J.-M.; Cohen, M.; Faure, C.; Mazouni, C.; Chauvet, M.-P.; Jouve, E.; Darai, E.; Azuar, A.-S.; et al. Early breast cancer in women aged 35 years or younger: A large national multicenter French population-based case control-matched analysis. Breast 2023, 68, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMasters, T.J.; Madhavan, S.S.; Sambamoorthi, U.; Vyas, A.M. Disparities in the Initial Local Treatment of Older Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Population-Based Study. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yood, M.U.; Owusu, C.; Buist, D.S.M.; Geiger, A.M.; Field, T.S.; Thwin, S.S.; Lash, T.L.; Prout, M.N.; Wei, F.; Quinn, V.P.; et al. Mortality impact of less-than-standard therapy in older breast cancer patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2008, 206, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesarova, P. Breast cancer in the elderly-Should it be treated differently? Rep. Pr. Oncol. Radiother. 2012, 18, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortadellas, T.; Córdoba, O.; Gascón, A.; Haladjian, C.; Bernabeu, A.; Alcalde, A.; Esgueva, A.; Rodriguez-Revuelto, R.; Espinosa-Bravo, M.; Díaz-Botero, S.; et al. Surgery improves survival in elderly with breast cancer. A study of 465 patients in a single institution. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 41, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchardy, C. Undertreatment Strongly Decreases Prognosis of Breast Cancer in Elderly Women. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3580–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiderlen, M.; van de Water, W.; Bastiaannet, E.; de Craen, A.J.M.; Westendorp, R.G.J.; van de Velde, C.J.H.; Liefers, G.-J. Survival and relapse free period of 2926 unselected older breast cancer patients: A FOCUS cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015, 39, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonberg, M.A.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Li, D.; Silliman, R.A.; Ngo, L.; McCarthy, E.P. Breast cancer among the oldest old: Tumor characteristics, treatment choices, and survival. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2038–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angarita, F.A.; Chesney, T.; Elser, C.; Mulligan, A.M.; McCready, D.R.; Escallon, J. Treatment patterns of elderly breast cancer patients at two Canadian cancer centres. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 41, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Freeman, J.L.; Nattinger, A.B.; Goodwin, J.S. Survival of women after breast conserving surgery for early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2002, 72, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roder, D.; Farshid, G.; Kollias, J.; Koczwara, B.; Karapetis, C.; Adams, J.; Joshi, R.; Keefe, D.; Miller, C.; Powell, K.; et al. Female breast cancer management and survival: The experience of major public hospitals in South Australia over 3 decades-trends by age and in the elderly. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2017, 23, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meresse, M.; Bouhnik, A.-D.; Bendiane, M.-K.; Retornaz, F.; Rousseau, F.; Rey, D.; Giorgi, R. Chemotherapy in Old Women with Breast Cancer: Is Age Still a Predictor for Under Treatment? Breast J. 2016, 23, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strader, L.A.; Helmer, S.D.; Yates, C.L.; Tenofsky, P.L. Octogenarians: Noncompliance with breast cancer treatment recommendations. Am. Surg. 2014, 80, 1119–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamtani, A.; Gonzalez, J.J.; Neo, D.; Slanetz, P.J.; Houlihan, M.J.; Herold, C.I.; Recht, A.; Hacker, M.R.; Sharma, R. Early-Stage Breast Cancer in the Octogenarian: Tumor Characteristics, Treatment Choices, and Clinical Outcomes. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 3371–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, A.; Narui, K.; Sugae, S.; Shimizu, D.; Takabe, K.; Ichikawa, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Endo, I. Operation with less adjuvant therapy for elderly breast cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2016, 204, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, R.V.; Chandru Kowdley, G. Treatment practices and outcomes of elderly women with breast cancer in a community hospital. Am. Surg. 2014, 80, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Water, W.; Bastiaannet, E.; Egan, K.M.; de Craen, A.J.M.; Westendorp, R.G.J.; Balducci, L.; van de Velde, C.J.; Liefers, G.-J.; Extermann, M. Management of primary metastatic breast cancer in elderly patients—An international comparison of oncogeriatric versus standard care. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2014, 5, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joerger, M.; Thürlimann, B.; Savidan, A.; Frick, H.; Rageth, C.; Lütolf, U.; Vlastos, G.; Bouchardy, C.; Konzelmann, I.; Bordoni, A.; et al. Treatment of breast cancer in the elderly: A prospective, population-based Swiss study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2013, 4, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: Patient-level meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Lancet 2015, 386, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Gray, R.; Braybrooke, J.; Davies, C.; Taylor, C.; McGale, P.; Peto, R.; Pritchard, K.I.; Bergh, J.; Dowsett, M.; et al. 20-Year Risks of Breast-Cancer Recurrence after Stopping Endocrine Therapy at 5 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Boyle, F.; Toi, M.; Broom, R.; Blancas, I.; Gumus, M.; Yamashita, T.; Im, Y.-H.; Rastogi, P.; et al. Adjuvant abemaciclib combined with endocrine therapy for high-risk early breast cancer: Safety and patient-reported outcomes from the monarchE study. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slamon, D.J.; Fasching, P.A.; Hurvitz, S.; Chia, S.; Crown, J.; Martín, M.; Barrios, C.H.; Bardia, A.; Im, S.A.; Yardley, D.A.; et al. Rationale and trial design of NATALEE: A Phase III trial of adjuvant ribociclib + endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone in patients with HR+/HER2- early breast cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2023, 15, 17588359231178125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaney, S.M.; Guarneri, V.; Seo, J.H.; Cruz, J.; Abreu, M.H.; Takahashi, M.; Barrios, C.; McIntyre, K.; Wei, R.; Munoz, M.; et al. Long-term patient-reported outcomes from monarchE: Abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy as adjuvant therapy for HR+, HER2-, node-positive, high-risk, early breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2024, 199, 113555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, P.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Martin, M.; Boyle, F.; Cortes, J.; Rugo, H.S.; Goetz, M.P.; Hamilton, E.P.; Huang, C.S.; Senkus, E.; et al. Adjuvant Abemaciclib Plus Endocrine Therapy for Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative, High-Risk Early Breast Cancer: Results from a Preplanned monarchE Overall Survival Interim Analysis, Including 5-Year Efficacy Outcomes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamon, D.J.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Yardley, D.A.; Huang, C.-S.; Fasching, P.A.; Crown, J.; Bardia, A.; Chia, S.; Im, S.-A.; Martin, M.; et al. Ribociclib and endocrine therapy as adjuvant treatment in patients with HR+/HER2- early breast cancer: Primary results from the phase III NATALEE trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, LBA500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, K.M.; Peachey, J.R.; Method, M.; Grimes, B.R.; Brown, J.; Saverno, K.; Sugihara, T.; Cui, Z.L.; Lee, K.T. A real-world US study of recurrence risks using combined clinicopathological features in HR-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 2667–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.R.; Brown, J.; Morikawa, A.; Method, M. Breast cancer-specific mortality in early breast cancer as defined by high-risk clinical and pathologic characteristics. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curigliano, G.; Dent, R.; Earle, H.; Modi, S.; Tarantino, P.; Viale, G.; Tolaney, S.M. Open Questions, Current Challenges, and Future Perspectives in Targeting Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Low Breast Cancer. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nonneville, A.; Houvenaeghel, G.; Cohen, M.; Sabiani, L.; Bannier, M.; Viret, F.; Gonçalves, A.; Bertucci, F. Pathological Complete Response Rate and Disease-Free Survival after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients with HER2-Low and HER2-0 Breast Cancers. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 176, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Nonneville, A.; Finetti, P.; Boudin, L.; Usclade, L.; Viens, P.; Viret, F.; Mamessier, E.; Gonçalves, A.; Bertucci, F. Abstract PO3-02-07: HER2-Low Status in Inflammatory Breast Cancer (IBC) Is Associated with Hormone Receptors Positivity but Not with Pathological Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy or Overall Survival. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, PO3-02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlino, F.; Diana, A.; Ventriglia, A.; Piccolo, A.; Mocerino, C.; Riccardi, F.; Bilancia, D.; Giotta, F.; Antoniol, G.; Famiglietti, V.; et al. HER2-Low Status Does Not Affect Survival Outcomes of Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer (MBC) Undergoing First-Line Treatment with Endocrine Therapy plus Palbociclib: Results of a Multicenter, Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Nonneville, A.; Finetti, P.; Boudin, L.; Usclade, L.; Mescam, L.; Durieux, E.; Boucraut, A.; Viret, F.; Mamessier, E.; Gonçalves, A.; et al. Abstract PO4-05-06: Hormone Receptor-Positive HER2-Low Metastatic Breast Cancer (mBC): Evolution of HER2 Status after CDK4/6 Inhibitor Treatment. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, PO4-05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadbad, M.A.; Safaei, S.; Brunetti, O.; Derakhshani, A.; Lotfinejad, P.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Hemmat, N.; Racanelli, V.; Solimando, A.G.; Argentiero, A.; et al. A Systematic Review on the Therapeutic Potentiality of PD-L1-Inhibiting MicroRNAs for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Toward Single-Cell Sequencing-Guided Biomimetic Delivery. Genes 2021, 12, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).