Menopausal Hormone Therapy in Breast Cancer Survivors

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

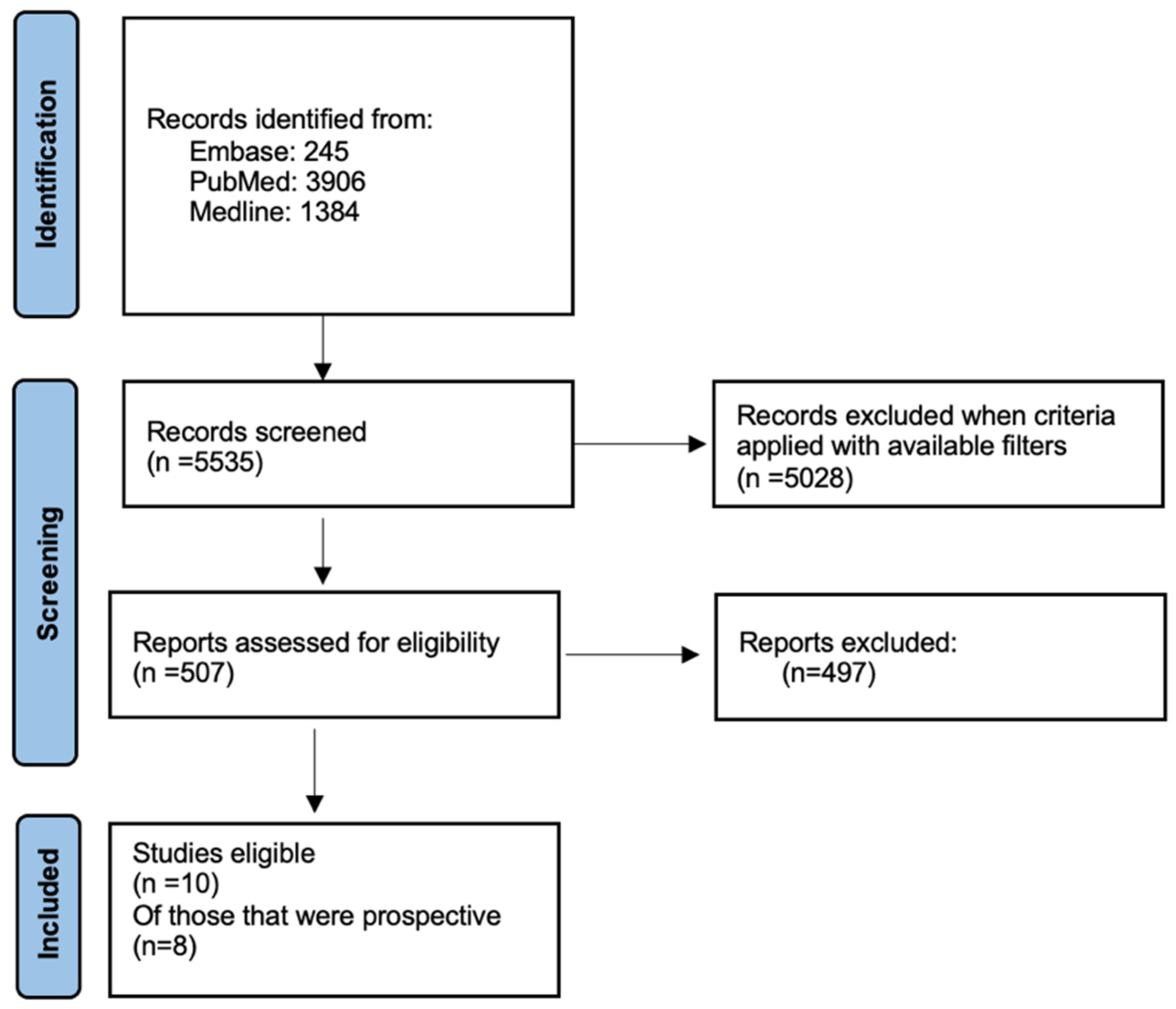

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Randomized Control Trials

3.2. Prospective Observational Cohort Studies

| First Author (Year) | Total, n | Recurrence, n (%) | Mean Follow Up (Years) | Odds Ratio for Recurrence | ER+, n (%) | Type of MHT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marttunen (2001) [20] | 2.5 | ERT/ERT + MPA | ||||

| -MHT | 88 | 7 (8.0%) | 0.7 | 57 (64.7%) | ||

| -No MHT | 43 | 5 (11.6%) | 29 (67.4%) | |||

| Decker (2003) [23] | 3.7 | ERT/ERT + Progestins/ Methyltestosterone | ||||

| -MHT | 271 | 30 (11%) | 0.8 | 100 (36.9%) | ||

| -No MHT | 277 | 35 (12.6%) | 121 (43.6%) | |||

| Dimitrakakis (2005) [22] | 5 | Tibolone | ||||

| -MHT | 52 | 1 (1.9%) | 0.8 | 42 (80.7%) | ||

| -No MHT | 104 | 3 (2.9%) | 78 (75%) | |||

| Cold (2022) [21] | 9.8 | ERT/ERT + P/VET | ||||

| -MHT | 2090 | 127 (6.1%) | 0.3 | 2090 (100%) | ||

| -Non-MHT | 6371 | 1206 (18.9%) | 6371 (100%) |

3.3. Current Attitudes of MHT in Breast Cancer Survivors

3.4. Strengths and Limitations of Our Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shuster, L.T.; Rhodes, D.J.; Gostout, B.S.; Grossardt, B.R.; Rocca, W.A. Premature menopause or early menopause: Long-term health consequences. Maturitas 2010, 65, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohoe, F.; O’meara, Y.; Roberts, A.; Comerford, L.; Kelly, C.M.; Walshe, J.M.; Lundy, D.; Hickey, M.; Brennan, D.J. Using menopausal hormone therapy after a cancer diagnosis in Ireland. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 192, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagani, O.; Francis, P.A.; Fleming, G.F.; Walley, B.A.; Viale, G.; Colleoni, M.; Láng, I.; Gómez, H.L.; Tondini, C.; Pinotti, G.; et al. Absolute Improvements in Freedom From Distant Recurrence to Tailor Adjuvant Endocrine Therapies for Premenopausal Women: Results From TEXT and SOFT. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 38, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Di Meglio, A.; Pistilli, B.; Gbenou, A.; El-Mouhebb, M.; Dauchy, S.; Charles, C.; Joly, F.; Everhard, S.; Lambertini, M.; et al. Differential impact of endocrine therapy and chemotherapy on quality of life of breast cancer survivors: A prospective patient-reported outcomes analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1784–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.; Davis, T. Ovarian Function in Patients Receiving Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer. Lancet 1977, 309, 1174–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistilli, B.; Paci, A.; Ferreira, A.R.; Di Meglio, A.; Poinsignon, V.; Bardet, A.; Menvielle, G.; Dumas, A.; Pinto, S.; Dauchy, S.; et al. Serum Detection of Nonadherence to Adjuvant Tamoxifen and Breast Cancer Recurrence Risk. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2762–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirgwin, J.H.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Coates, A.S.; Price, K.N.; Ejlertsen, B.; Debled, M.; Gelber, R.D.; Goldhirsch, A.; Smith, I.; Rabaglio, M.; et al. Treatment Adherence and Its Impact on Disease-Free Survival in the Breast International Group 1-98 Trial of Tamoxifen and Letrozole, Alone and in Sequence. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2452–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoi, M.A.; Agostinetto, E.; Perachino, M.; Del Mastro, L.; de Azambuja, E.; Vaz-Luis, I.; Partridge, A.H.; Lambertini, M. Evidence-based approaches for the management of side-effects of adjuvant endocrine therapy in patients with breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e303–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, L.; Anderson, H. HABITS (hormonal replacement therapy after breast cancer—Is it safe?), a randomised comparison: Trial stopped. Lancet 2004, 363, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlén, M.; Fornander, T.; Johansson, H.; Johansson, U.; Rutqvist, L.-E.; Wilking, N.; von Schoultz, E. Hormone replacement therapy after breast cancer: 10 year follow up of the Stockholm randomised trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulou-Sellin, R.; Cohen, D.S.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Klein, M.J.; McNeese, M.; Singletary, S.E.; Smith, T.L.; Theriault, R.L. Estrogen replacement therapy for menopausal women with a history of breast carcinoma. Cancer 2002, 95, 1817–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenemans, P.; Bundred, N.J.; Foidart, J.-M.; Kubista, E.; von Schoultz, B.; Sismondi, P.; Vassilopoulou-Sellin, R.; Yip, C.H.; Egberts, J.; Mol-Arts, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of tibolone in breast-cancer patients with vasomotor symptoms: A double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, L.; Iversen, O.-E.; Rudenstam, C.M.; Hammar, M.; Kumpulainen, E.; Jaskiewicz, J.; Jassem, J.; Dobaczewska, D.; Fjosne, H.E.; Peralta, O.; et al. Increased Risk of Recurrence After Hormone Replacement Therapy in Breast Cancer Survivors. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, F.; Del Mastro, L.; Bruzzone, M.; Ceppi, M.; Razeti, M.G.; Fregatti, P.; Ruelle, T.; Pronzato, P.; Massarotti, C.; Franzoi, M.A.; et al. Safety of systemic hormone replacement therapy in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 191, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambrinoudaki, I. Menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: All progestogens are not the same. Case Rep. Women’s Health 2021, 29, e00270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speroff, L. The LIBERATE tibolone trial in breast cancer survivors. Maturitas 2009, 63, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloosterboer, H.J. Tissue-selectivity: The mechanism of action of tibolone. Maturitas 2004, 48, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, J.; Sacks, N. The national randomised trial of hormone replacement therapy in women with a history of early stage breast cancer: An update. Br. Menopause Soc. J. 2002, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Col, N.F.; A Kim, J.; Chlebowski, R.T. Menopausal hormone therapy after breast cancer: A meta-analysis and critical appraisal of the evidence. Breast Cancer Res. 2005, 7, R535–R540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marttunen, M.B.; Hietanen, P.; Pyrhönen, S.; Tiitinen, A.; Ylikorkala, O. A prospective study on women with a history of breast cancer and with or without estrogen replacement therapy. Maturitas 2001, 39, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cold, S.; Cold, F.; Jensen, M.-B.; Cronin-Fenton, D.; Christiansen, P.; Ejlertsen, B. Systemic or Vaginal Hormone Therapy After Early Breast Cancer: A Danish Observational Cohort Study. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakakis, C.; Keramopoulos, D.; Vourli, G.; Gaki, V.; Bredakis, N.; Keramopoulos, A. Clinical effects of tibolone in postmenopausal women after 5 years of tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer. Climacteric 2005, 8, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, D.A.; Pettinga, J.E.; VanderVelde, N.; Huang, R.R.; Kestin, L.; Burdakin, J.H. Estrogen replacement therapy in breast cancer survivors: A matched-controlled series. Menopause 2003, 10, 277–285. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/menopausejournal/fulltext/2003/10040/estrogen_replacement_therapy_in_breast_cancer.4.aspx (accessed on 19 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Marsden, J.; Whitehead, M.; A’hern, R.; Baum, M.; Sacks, N. Are randomized trials of hormone replacement therapy in symptomatic women with breast cancer feasible? Fertil. Steril. 2000, 73, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulou-Sellin, R.; Klein, M.J. Estrogen replacement therapy after treatment for localized breast carcinoma: Patient responses and opinions. Cancer 1996, 78, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schoultz, E.; Rutqvist, L.E.; on Behalf of the Stockholm Breast Cancer Study Group. Menopausal Hormone Therapy After Breast Cancer: The Stockholm Randomized Trial. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallberg, B.; von Schoultz, E.; Bolund, C.; Bergh, J.; Wilking, N. Hormone replacement therapy after breast cancer: Attitudes of women eligible in a randomized trial. Climacteric 2009, 12, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossouw, J.E.; Anderson, G.L.; Prentice, R.L.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Kooperberg, C.; Stefanick, M.L.; Jackson, R.D.; Beresford, S.A.A.; Howard, B.V.; Johnson, K.C.; et al. Risks and Benefits of Estrogen Plus Progestin in Healthy Postmenopausal Women: Principal Results From the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2002, 288, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosignani, P.G. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 2003, 362, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, X.-B.; Peeters, F.; Tjalma, W.A. The thoughts of breast cancer survivors regarding the need for starting hormone replacement therapy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2006, 124, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, X.-B.; Van Hal, G.; Weyler, J.; Tjalma, W.A. The thoughts of physicians regarding the need to start hormone replacement therapy in breast cancer survivors. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2006, 124, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author (Trial) | Number of Patients | HR+, n (%) | HR−, n (%) | Type of MHT | Median Follow Up (Months) | Hazard Ratio (HR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vassilopoulou-Sellin | 77 | 0 | 54 (70.1) | Conjugated estrogen treatment | 71 | 0.52 |

| Holmberg (HABITS) | 442 | 261 (59) | 42 (9.5) | Continuous combined or sequential estradiol hemihydrate and norethisterone | 48 | 2.40 |

| Fahlen (STOCKHOLM) | 378 | 216 (57.1) | 51 (13.5) | Cyclic estradiol/MPA or estradiol alone | 120 | 1.30 |

| Kenemans (LIBERATE) | 3098 | 2185 (71) | 623 (20.1) | Tibolone | 36 | 1.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Culhane, R.; Zaborowski, A.M.; Hill, A.D.K. Menopausal Hormone Therapy in Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancers 2024, 16, 3267. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193267

Culhane R, Zaborowski AM, Hill ADK. Menopausal Hormone Therapy in Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancers. 2024; 16(19):3267. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193267

Chicago/Turabian StyleCulhane, Rose, Alexandra M. Zaborowski, and Arnold D. K. Hill. 2024. "Menopausal Hormone Therapy in Breast Cancer Survivors" Cancers 16, no. 19: 3267. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193267

APA StyleCulhane, R., Zaborowski, A. M., & Hill, A. D. K. (2024). Menopausal Hormone Therapy in Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancers, 16(19), 3267. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193267