The Local Rhombus-Shaped Flap—An Easy and Reliable Technique for Oncoplastic Breast Cancer Surgery and Defect Closure in Breast and Axilla

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

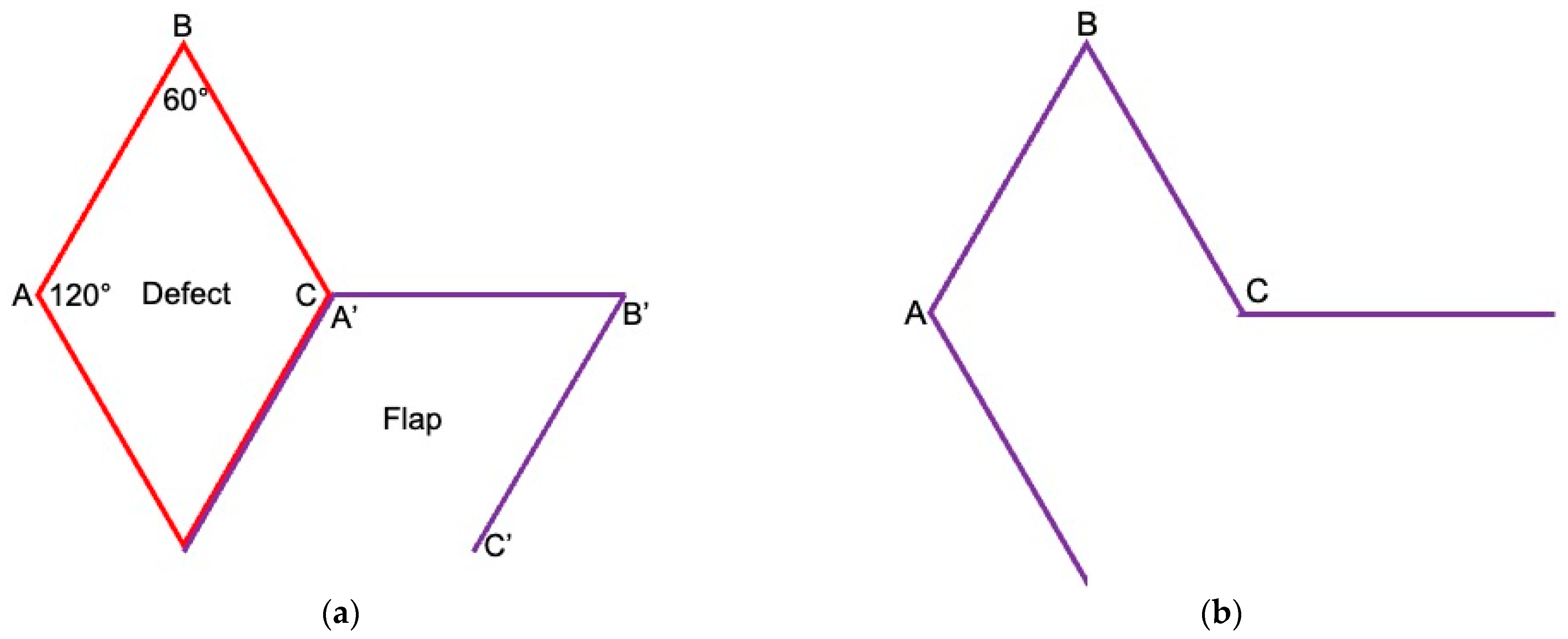

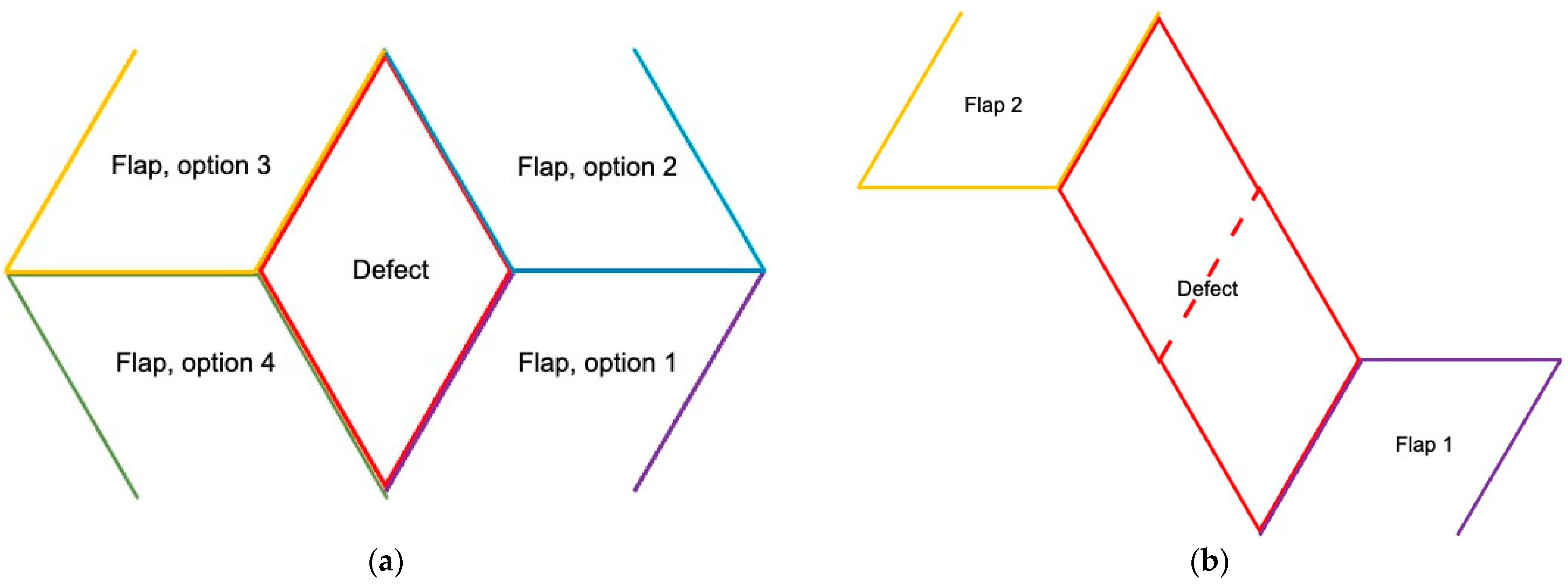

2. Surgical Technique

3. Results

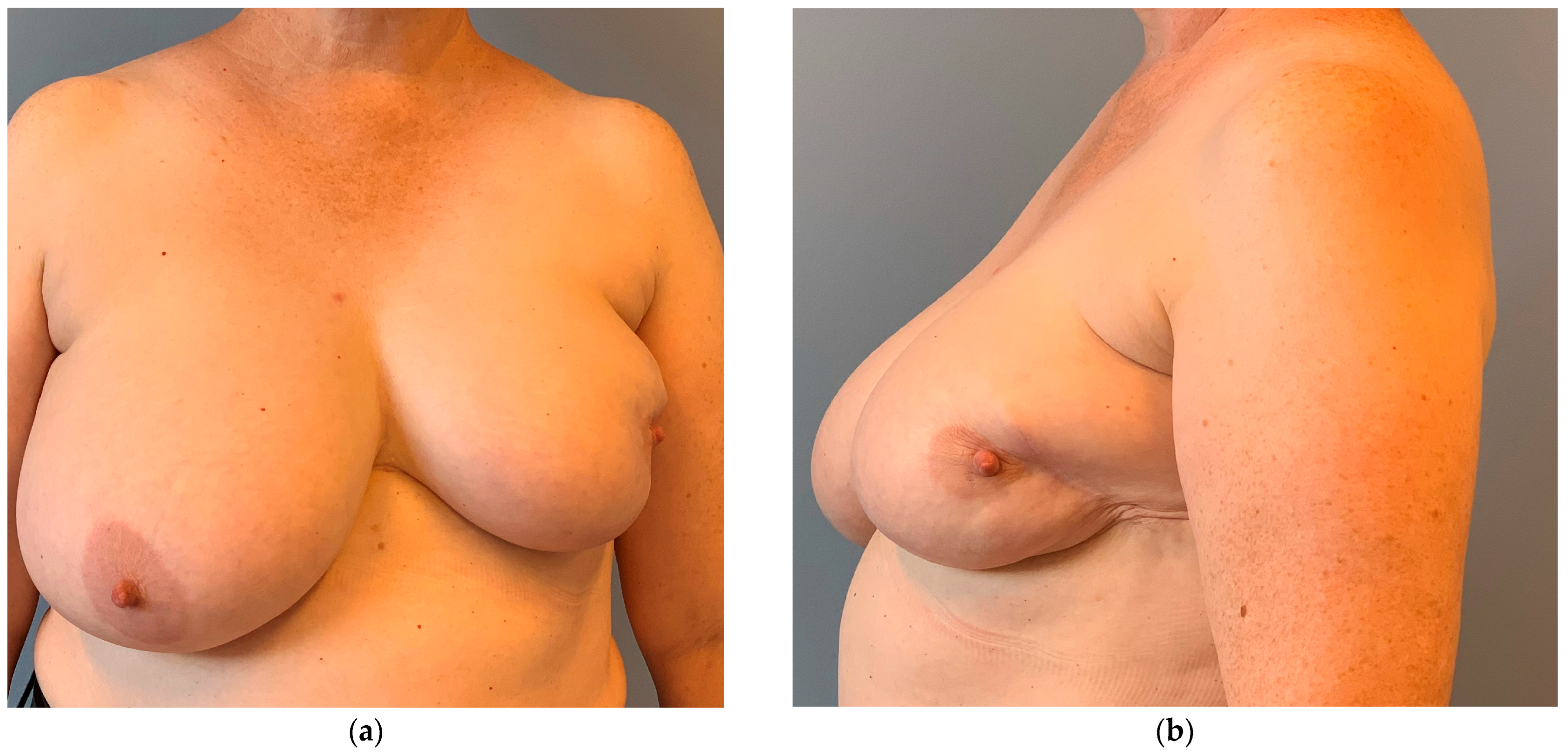

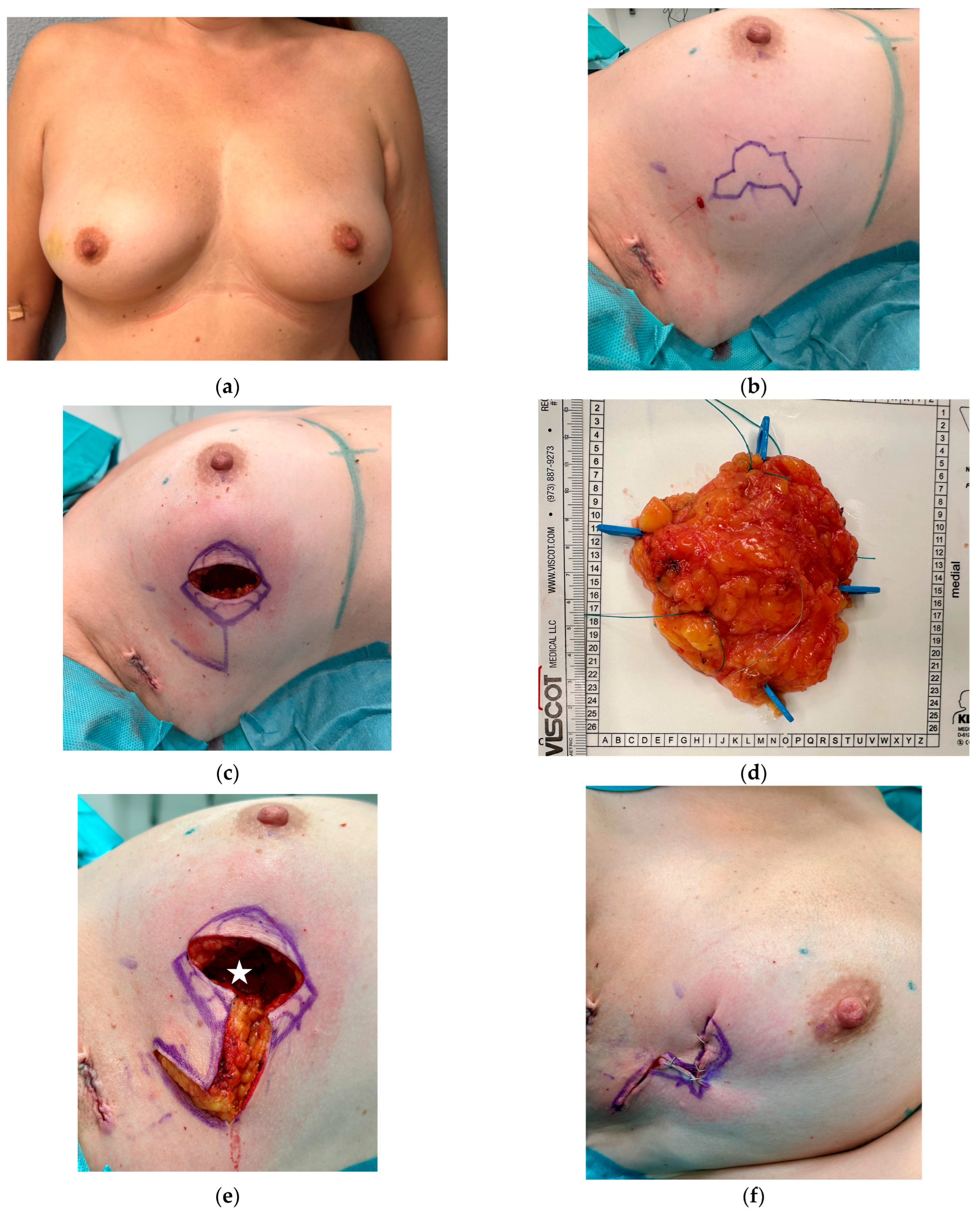

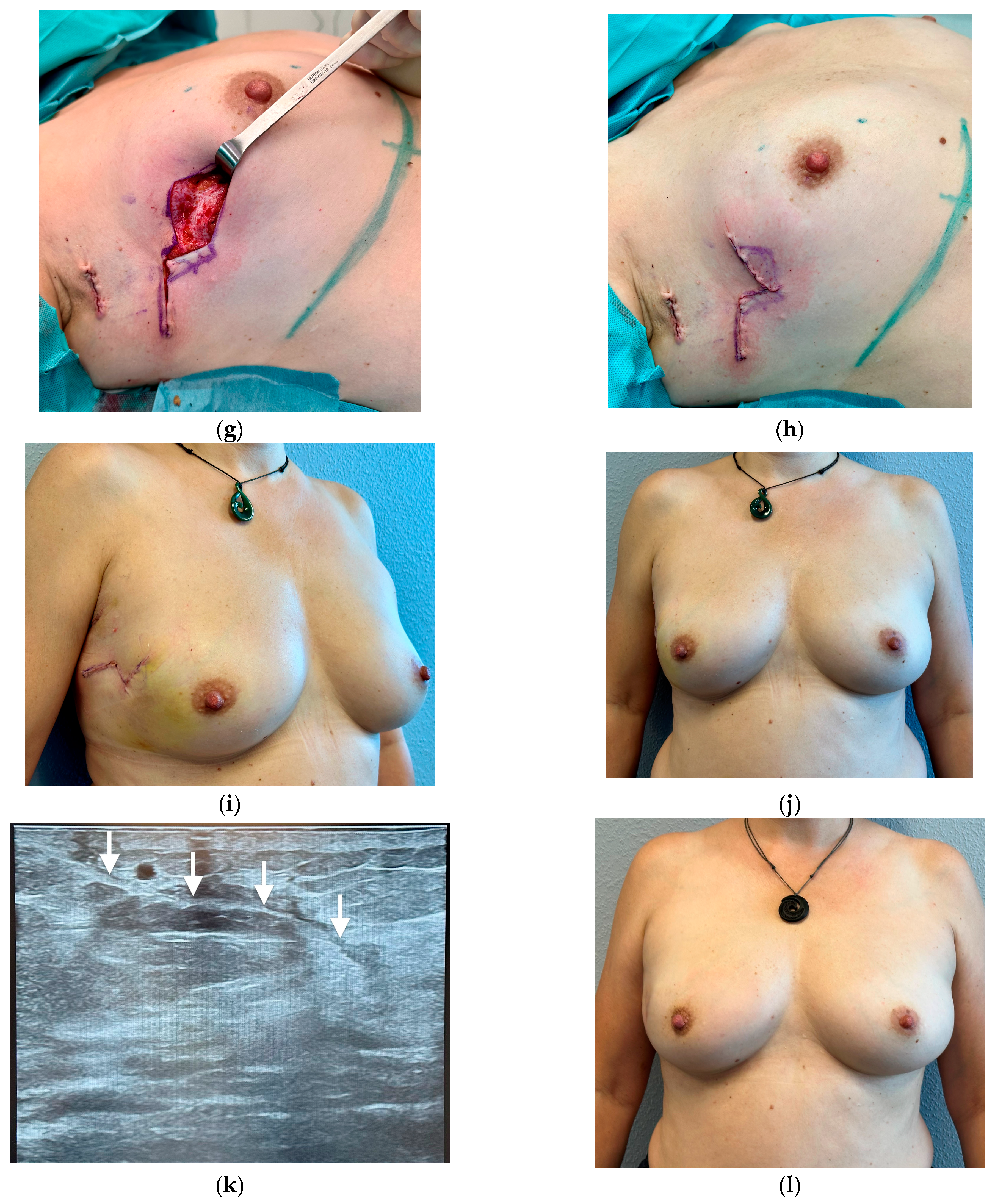

3.1. Breast Cancer with Skin Resection and Local Replacement from the Chest

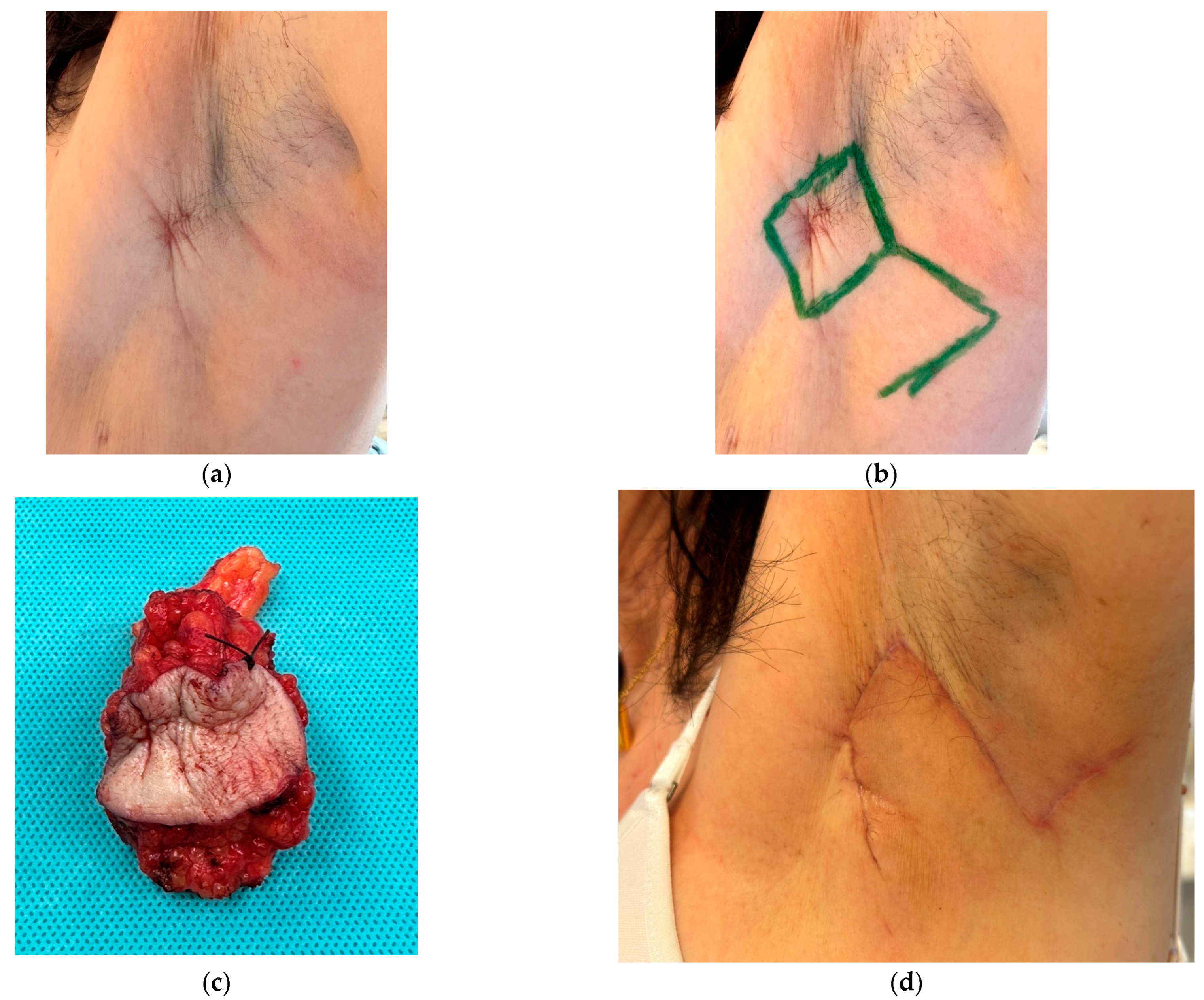

3.2. Axilla

3.3. Breast Cancer Resection and Volume Displacement with a Buried Flap

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gentilini, O.D.; Cardoso, M.J.; Poortmans, P. Less is more. Breast conservation might be even better than mastectomy in early breast cancer patients. Breast 2017, 35, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultze, J.; Lössl, K.; Kimmig, B. Cosmetic results after breast conserving carcinoma treatment in patients with intramammarian seromas. Rontgenpraxis 2008, 56, 169–180. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juneja, P.; Bonora, M.; Haviland, J.S.; Harris, E.; Evans, P.; Somaiah, N. Does breast composition influence late adverse effects in breast radiotherapy? Breast 2016, 26, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brands-Appeldoorn, A.T.P.M.; Thomma, R.C.M.; Janssen, L.; Maaskant-Braat, A.J.G.; Tjan-Heijnen, V.C.G.; Roumen, R.M.H. Factors related to patient-reported cosmetic outcome after breast-conserving therapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 191, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, S.A.; Lyons, G.R.; Kuerer, H.M.; Bassett, R.L.; Oates, S.; Thompson, A.; Caudle, A.S.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Bedrosian, I.; Lucci, A.; et al. Operative and Oncologic Outcomes in 9861 Patients with Operable Breast Cancer: Single-Institution Analysis of Breast Conservation with Oncoplastic Reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol 2016, 23, 3190–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell Pinto, T.; Mora, H.; Peleteiro, B.; Magalhães, A.; Gonçalves, D.; Fougo, J.L. Chest wall perforator flaps for partial breast reconstruction after conservative surgery: Prospective analysis of safety and reliability. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 51, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.D.; Lee, J.W.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, W.W.; Hwang, S.O.; Jung, J.H.; Park, H.Y. Surgical Techniques for Personalized Oncoplastic Surgery in Breast Cancer Patients with Small- to Moderate-Sized Breasts (Part 2): Volume Replacement. J. Breast Cancer 2012, 15, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Wong, D.E.; Hanson, S.E. Oncoplastic Techniques and Tricks to Have in Your Toolbox. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 153, 673e–682e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soumian, S.; Parmeshwar, R.; Chandarana, M.; Marla, S.; Narayanan, S.; Shetty, G. Chest wall perforator flaps for partial breast reconstruction: Surgical outcomes from a multicenter study. Arch. Plastic Surgery 2020, 47, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.A.D.C.; Paulinelli, R.R.; de Oliveira-Junior, I. Extreme oncoplasty: Past, present and future. Front. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1215284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gwynn, B.R.; Williams, C.R. Use of the Limberg flap to close breast wounds after partial mastectomy. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 1985, 67, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Menekşe, E.; Özyazıcı, S.; Karateke, F.; Turan, Ü.; Kuvvetli, A.; Gökler, C.; Özdoğan, M.; Önel, S. Rhomboid Flap Technique in Breast-conserving Surgery: An Alternative Method for the Reconstruction of Lumpectomy Defects. J. Breast Health 2015, 11, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xue, B.; Wang, X.; Pei, X. Aesthetic reconstruction of a partial breast defect with a rhomboid flap following wide surgical excision of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Asian J. Surg. 2022, 45, 2066–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivace, B.J.; Kachare, S.D.; Ablavsky, M.; Abell, S.R.; Meredith, L.T.; Kapsalis, C.N.; Choo, J.H.; Wilhelmi, B.J. Breast Reconstruction with Local Flaps: Don’t Forget Grandma. Eplasty 2019, 19, e23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Limberg, A.A. Planimetrie und Stereometrie der Hautplastik; Gustav Fischer Verlag: Jena, Germany, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, G.D.; Gibson, T. Closure of rhomboid skin defects: The flaps of Limberg and Dufourmentel. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1972, 25, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altmann, S.; Fansa, H.; Schneider, W. Surgical treatment of axillary hidradenitis suppurativa. Chirurg 2001, 72, 1413–1416. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macneal, P.; Hohman, M.H.; Adlard, R.E. Rhombic Flaps 18 April 2024. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silverstein, M.J.; Mai, T.; Savalia, N.; Vaince, F.; Guerra, L. Oncoplastic breast conservation surgery: The new paradigm. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 110, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaviani, A.; Tabary, M.; Zand, S.; Araghi, F.; Patocskai, E.; Nouraie, M. Oncoplastic Repair in Breast Conservation: Comprehensive Evaluation of Techniques and Oncologic Outcomes of 937 Patients. Clin. Breast Cancer 2020, 20, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.A.; Ash, M.E.; Styblo, T.M.; Carlson, G.W.; Losken, A. The Modified Frailty Index Predicts Major Complications in Oncoplastic Reduction Mammoplasty. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2024, 92 (Suppl. 6S), S372–S375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fansa, H. Oncoplastic Surgery. In Breast Surgery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohmert, H. Experience in breast reconstruction with thoraco-epigastric and advancement flaps. Acta Chir. Belg. 1980, 79, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schaverien, M.V.; Kuerer, H.M.; Caudle, A.S.; Smith, B.D.; Hwang, R.F.; Robb, G.L. Outcomes of Volume Replacement Oncoplastic Breast-Conserving Surgery Using Chest Wall Perforator Flaps: Comparison with Volume Displacement Oncoplastic Surgery and Total Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 146, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, W.; Stallard, S.; Doughty, J.; Mallon, E.; Romics, L. Oncological Outcomes and Complications after Volume Replacement Oncoplastic Breast Conservations-The Glasgow Experience. Breast Cancer 2016, 10, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kapadia, S.M.; Reitz, A.; Hart, A.; Broecker, J.; Torres, M.A.; Carlson, G.W.; Styblo, T.M.; Losken, A. Time to Radiation After Oncoplastic Reduction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2019, 82, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonci, E.A.; Anacleto, J.C.; Cardoso, M.J. Sometimes it is better to just make it simple. De-escalation of oncoplastic and reconstructive procedures. Breast 2023, 69, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sebastian, M.; Sroczyński, M.; Rudnicki, J. The Dufourmentel modification of the Limberg flap: Does it fit all? Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 26, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, S.; Nohara, T.; Nakatani, S.; Iwamoto, M.; Sumiyoshi, K.; Kimura, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Sato, N.; Tanigawa, N. Esthetic result of rhomboid flap repair after breast-conserving surgery for lower quadrant breast cancer lesion with skin invasion: Report of two cases. Surg. Today 2011, 41, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Morioka, J. Two Cases of Breast Reconstruction with a Limberg Flap. J.-Stage 2016, 41, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Neto, M.P.; Adão, O.; Scandiuzzi, D.; Chaem, L.H. The rhomboid flap for immediate breast reconstruction after quadrantectomy and axillary dissection. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007, 119, 1134–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargavan, R.V.; Augustine, P.; Cherian, K. Limberg Flap in Breast Oncoplasty for Carcinoma Breast Revisited-a Tertiary Cancer Centre Experience. Indian. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 13, 876–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quaba, A.A.; Sommerlad, B.C. “A square peg into a round hole”: A modified rhomboid flap and its clinical application. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1987, 40, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fansa, H.; Linder, S. The Local Rhombus-Shaped Flap—An Easy and Reliable Technique for Oncoplastic Breast Cancer Surgery and Defect Closure in Breast and Axilla. Cancers 2024, 16, 3101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16173101

Fansa H, Linder S. The Local Rhombus-Shaped Flap—An Easy and Reliable Technique for Oncoplastic Breast Cancer Surgery and Defect Closure in Breast and Axilla. Cancers. 2024; 16(17):3101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16173101

Chicago/Turabian StyleFansa, Hisham, and Sora Linder. 2024. "The Local Rhombus-Shaped Flap—An Easy and Reliable Technique for Oncoplastic Breast Cancer Surgery and Defect Closure in Breast and Axilla" Cancers 16, no. 17: 3101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16173101

APA StyleFansa, H., & Linder, S. (2024). The Local Rhombus-Shaped Flap—An Easy and Reliable Technique for Oncoplastic Breast Cancer Surgery and Defect Closure in Breast and Axilla. Cancers, 16(17), 3101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16173101