Simple Summary

Despite advances in head and neck cancer control, survivors encounter significant difficulties accessing survivorship care in the USA. We conducted a qualitative study aimed to better understand their experiences and identify unmet needs. Fifteen long-term head and neck cancer survivors were interviewed, where themes around chronic emotional distress, fatigue, and disruptions in daily life emerged across the focus group. Secondary issues included sleep problems, cognitive difficulties, and other health conditions. Surprisingly, physical symptoms like pain and changes in appetite were less discussed. These findings underscore the need for tailored holistic multi-dimensional cancer survivorship programs that address physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. The study highlights the importance of increased awareness and comprehensive long-term support to prioritize and enhance quality of life for the head and neck cancer survivorship community.

Abstract

Improved rates of cancer control have increased the head and neck cancer survivor population. Cancer survivorship clinics are not widely available in the USA, and longitudinal supportive care for patients undergoing multimodal therapy has not advanced at a pace commensurate with improvements in cancer control. Consequently, a large head and neck cancer survivor population whose quality of life may be chronically and/or permanently diminished presently exists. This lack of awareness perpetuates under-recognition and under-investigation, leaving survivors’ (mostly detrimental) experiences largely uncharted. We conducted a qualitative exploration of survivors’ experiences, aiming to unpack the profound impact of late systemic symptoms on daily life, encompassing work, relationships, and self-identity in the head and neck cancer survivor community. The study included 15 remitted head and neck survivors, ≥12 months from their final treatment, who participated in semi-structured interviews conducted by a medical oncologist. Data analysis comprised qualitative thematic analysis, specifically inductive hierarchical linear modeling, enriched by a deductive approach of anecdotal clinical reporting. Results highlighted that 43.36% of all quotation material discussed in the interviews pertained to chronic emotion disturbance with significant implications for other domains of life. A central symptom cluster comprised impairments in mood/emotions, daily activity, and significant fatigue. Dysfunction in sleep, other medical conditions, and cognitive deficits comprised a secondary cluster. Physical dysfunctionality, encompassing pain, appetite, and eating, and alterations in experienced body temperature, constituted a tertiary cluster, and perhaps were surprisingly the least discussed symptom burden among head and neck cancer survivors. Symptoms causing heightened long-term survivor burden may be considered epiphenomenal to central physical dysfunctionality, albeit being presently the least represented in cancer survivor care programs. Moving forward, the development of targeted and multi-dimensional treatment programs that encompass physical, psychosocial, and spiritual domains are needed to increase clinical specificity and effective holistic long-term solutions that will foster a more compassionate and informed future of care for the cancer survivorship community.

1. Introduction

Head and neck cancer ranks as the eighth most prevalent cancer worldwide, and is predicted to be responsible for more than 58,000 newly diagnosed cases in the United States in 2024 [1]. More than two-thirds of new head and neck cancer cases present at a locally advanced stage, for which multimodality treatment including surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy has resulted in improved disease control and survival, constituting the standard of care [2]. Owing to improved rates of cancer control, the head and neck cancer survivor population continues to grow at an unprecedented rate [3]. While the term cancer “survivor” is defined variably in the literature and by patient advocacy organizations [4], both sub-populations, i.e., patients living with, and after head and neck cancer, are demonstrating substantial growth [3]. Supportive care for acute treatment toxicities has improved meaningfully over the past two decades [5,6], although longitudinal supportive care for patients undergoing multimodal therapy is presently not advancing at a pace commensurate with improvements in acute symptom management or cancer control. This has resulted in a growing cancer survivor population whose quality of life may be chronically, and in many cases permanently, diminished [7,8,9,10,11,12].

Chronic toxicities and symptoms from head and neck cancer and/or its therapy may include locoregional side effects such as adverse dental effects or tooth loss [13,14], lymphedema [15], swallowing dysfunction [16], pain [17,18], and other localized suffering. However, more generalized symptoms include, but are not limited to, fatigue, thermal discomfort, appetite problems, sleep disturbance, and mood disorders, which are considered systemic in nature [19]. Both local and systemic symptoms can be noted prior to, during, or even months after completing cancer treatment, and both local and generalized/systemic adverse effects may persist months or even years longer than previously recognized [20,21]. Whilst novel interventions are being developed and implemented for the mitigation of, and prophylaxis for, local toxicities [22,23,24,25,26], the lack of published data characterizing chronic systemic symptoms has hindered meaningful research into management and prevention strategies [27]. It has been noted that late systemic symptoms tend to occur in clusters [28], suggesting a common underlying pathobiology. However, a comprehensive investigation into the mechanisms and pathways contributing to systemic symptoms has yet to be undertaken. Preliminary evidence suggests that inflammation [29], specifically, pro-inflammatory cytokines instigated by the native immune response or treatment effects from head and neck cancer treatment, may result in a state of chronic, centralized inflammation and chronic, systemic symptom burden—a hypothesis that has yet to be fully developed [30,31,32]. Recently, we presented the first data supporting such a proof-of-concept with scope for all non-central nervous system cancers, including the head and neck cancer sub-population. Our new data found increased microglial activation in long-term head and neck cancer survivors, versus matched healthy controls, that was specifically linked to chronic systemic symptomatology [33]. These data were particularly interesting given that other markers of inflammation and neurodegenerative decline, such as peripheral blood inflammatory markers or neurovascular measures of white tract integrity, did not correlate with chronic systemic symptoms [33], supporting a peripheral-to-centralized neuroinflammatory basis of such symptomatology.

The focus of this report pertains to the general lack of clinician and investigator awareness of systemic symptomatology, which (a) serves to perpetuate the under-recognition and under-investigation of meaningful innovation in this domain of clinical study and care, and (b) allows head and neck cancer survivors’ experiences and struggles to be largely medically and experientially unchartered. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published comprehensive qualitative data regarding the extent and impact of these experiences among head and neck cancer survivors. To address this gap in the knowledge, we conducted a qualitative study, aiming to unravel the head and neck cancer survivor experience and the profound impact of late systemic symptoms on daily life, encompassing work, relationships, and self-identity. A driving goal of this study was to amplify survivors’ voices, empower the survivorship community, and foster a more compassionate and informed future for head and neck cancer survivorship support. By including a diverse sample of survivors from various socio-economic backgrounds and catchment areas, we sought to better understand the unique challenges and needs of these individuals, ultimately paving the way for more equitable and effective survivorship care programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Recruitment

Fifteen patients (eleven male, four female) were recruited from the Henry Joyce Cancer Clinic at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center between November 2014 and November 2016, a subset from a wider cohort of 105 enrolled in a clinical trial, for the reported qualitative analysis. The qualitative study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Scientific Review Committee at Vanderbilt University, and all patients provided signed informed consent prior to interviews. Potential patients were identified through review of medical records and were eligible to participate in the qualitative interview if they met the following criteria: (1) ≥21 years of age, (2) at least one moderate to severe systemic symptom, (3) prior histologic diagnosis of head and neck cancer, (4) ≥12 months after completing all head and neck cancer treatment, (5) no current evidence of cancer, (6) able to speak English, and (7) able to provide informed consent.

2.2. Data Collection

Interviews were semi-structured and ranged from 10 to 70 min. The interview guide was developed from the medical consensus and specific questions from head and neck cancer healthcare providers. Interviews elicited information about patients’ chronic systemic symptoms during and following their head and neck cancer treatment. Questions encompassed multiple domains including quality of life, interpersonal relationships, professional functioning, and identity. Follow-up questions were asked for clarity and to promote detailed discussion of survivors’ experiences. All interviews were conducted by the same trained interviewer (EWB), recorded, and transcribed (www.Rev.com (accessed on 17 May 2024)) prior to de-identification. Transcripts were reviewed and checked for quality assessment by EWB and another trained staff member (BAM) who was not involved in either interviewing patients or the transcription process. Data saturation was determined by the research team and recruitment of new patients ceased once data saturation was reached. Data saturation comprised a judgement as to whether or not new information was emerging from the most recent interviews.

2.3. Data Analysis

Transcribed interviews were analyzed by the Vanderbilt University Qualitative Research Core using thematic analysis. Data coding and analysis were led by a PhD-level psychologist (DGS) following COREQ guidelines [34], and implemented by a trained qualitative researcher (KRB). A hierarchical coding system was developed and refined using the interview guide and a preliminary review of the transcripts. Definitions and rules were written for the use of each category. Five major categories were identified, which were further branched into fourteen subcategories, some with additional hierarchical divisions. The final coding system included the following 16 overall categories: (1) Fatigue; (2) Sleep; (3) Cognition; (4) Body Temperature; (5) Emotions; (6) Appetite and Food; (7) patient’s Medical Condition; (8) Aches and Pain; (9) Daily Activities; (10) Relationships; (11) Symptom Improvement; (12) Declining Trajectory; (13) Delayed Symptom Onset; (14) Disability; (15) Coping Strategies; and (16) Spirituality. See Supplementary Materials: (https://healthbehavior.psy.vanderbilt.edu//Wulff/Wulff_CodingSystem.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2024)).

Each statement was treated as a separate quotation, with each quotation assigned up to six codes. Inter-rater reliability was established by two investigators separately coding transcripts, reconciling their codes, and establishing inter-rater consensus. Codes were then analyzed using an iterative inductive–deductive approach. The deductive approach was guided by significant clinical experience in caring with head and neck cancer patients, in addition to the research literature on cancer symptoms and quality of life. Inductively, we sorted the codes in statistical software to synthesize the data into higher-order themes using hierarchical linear modeling.

3. Results

Emotions were the most frequently discussed symptoms by patients as a whole (43.36%), followed by Daily Activities (32.16%) and Fatigue (31.64%). Table 1 outlines the mean percentage of quotations for each category, which were also calculated when weighting the individual data quota to the full sample. Exemplary quotations extracted from the interview data are further reported below, and in Table 2. Only categories discussed in ≥10% of interview data across the patient pool are discussed.

Table 1.

Mean percentage each theme was discussed across all interviews.

Table 2.

Exemplary quotations across the entire cohort for the main themes discussed, and comprising at least 10% of all quotations.

3.1. Mood and Emotion Dysregulation

The most common long-term burden, experienced by all patients, pertained to emotions as opposed to direct physical symptoms, constituting 43.26% of discussions during the interviews. Naturally, stress became a significant burden; dealing with symptoms and the threat of cancer returning all served to amplify the stressors of everyday living: “It’s like I can’t handle what I used to could handle. I used to could handle a whole lot of stress and I used to could handle pressure…I cannot now [sic]”.

Feelings of anxiety were commonly reported, with some patients reporting anxiety around specific triggers, and others a generalized anxiety, that further compacted other dimensions of symptomatology. Sudden onset of anxiety was also reported that was not necessarily related to fear of cancer: “I’ve had some problems with anxiety…One of the nice things about being so ill is I’m not afraid of dying…I don’t want to do is to be disabled and live a long time.”; but longer term consequences from treatments; “…my anxiety towards eating, swallowing and going grocery shopping that’s cause the worst anxiety throughout whole day now [sic]…I’ll have an episode…It’s all tied into my eating and choking”.

Depression was common, with generally an insidious onset: “I think that the depression started gradually over the following year…I didn’t just wake up one day tired and depressed. It was a slow, gradual thing that occurred about six months after treatment”.

Some patients reported severe and intense depression: “I think about killing myself”, “Yes, depression is pervasive”, “[depression] it impacts me on a daily basis”.

Depressive symptoms would limit help seeking and social support behaviors causing further detriment: “If I am depressed, I really don’t want to associate with anybody [inaudible 00:37:37]”.

The misfortune of both anxiety and depression also persisted longer term: “[depression and anxiety]…been gradually getting worse for the last 8 or 10 years, since I had first gotten cancer”.

Emotional dysfunction had a detrimental impact on self-esteem and identity, such as: “It’s played a large role in my self-worth, because as a guy not working, it’s wiped out a lot of my self-worth”, “Sometimes I don’t feel worthy.”, “I went on disability which did the transition for me just mentally to think that I’m disabled, and that has been part of the whole depression thing too”, and “It makes me feel less of a person that I used to be”.

3.2. Daily Activities

Significant burden around daily activities was the second most discussed. Cumulatively, symptoms severely impacted professional, social, interpersonal, and recreational activities. Being able to continue in employment, or conduct their work properly, was a major issue for many patients: “I couldn’t work 40 h for anyone I know that, but I’m learning how to manage it better”.

Hindrance in the simplest of daily physical activities were also reported due to lack of vigor: “I’m not as strong as I was … like this morning, opening up a box of cereal in here and trying to pull the cereal itself, the plastic, apart. I can get it, but it’s pretty tough.”, and “I’ve had several [inaudible 00:09:35] a bath because I’m not strong enough to pull myself out of the bathtub.”, and “If I walk across the yard and back I have to set down. I put it that way.”, further to mobility issues; “It really affects my ability to drive, that’s why my wife do a lot of driving. I don’t have the full range of motion that I want to turn my neck from side to side”.

3.3. Fatigue and Sleep

Fatigue was the third most common burden discussed by 14 patients, and sleep challenges were the fourth more commonly discussed issue experienced by all patients. Sleeping problems and fatigue were believed to be “brought on by treatments”, “…the chemo radiation”, but didn’t dissipate once treatment ceased: “I kept sleeping more and more after cancer treatment, so a year after cancer treatment is when I was sleeping fifteen hours a day, and it wasn’t insomnia”.

Treatment sometimes damaged other organs: “My thyroid was damaged, so I’m a thyroxine [sic]”, causing additional long-term complications for metabolism and sleep.

A large portion of patients described fatigue as episodic, whereas others described sleep-related symptoms as relentless: “It’s not like I can just go to sleep and get a real good night’s sleep”.

Sleep disturbances were reported as causing global weakness and compromised immune function: “Every time I wind up with pneumonia, I come out a little weaker…Being that I can’t drink or eat anything anymore, all I’m getting is Ensure through my belly…”, which persisted into a longer-term symptom burden: “I get weaker all the time. Over the months.”, and “Much worse, yes, than it used to be 2 or 3 years ago”.

Patterns, such as being more fatigued in the morning, or related to exertion, were reported: “The harder I do anything, or try to do stuff, the more it wears me out”.

In addition to fatigue, participants described impediments to falling or staying sleep, poor sleep quality, and undertaking modifications to promote sleep: “I don’t sleep all the way through the night. When I go to sleep, I probably sleep for four or five hours. Then I’ll wake up.”, and “I used to be able to sleep through the night. Now I sleep [inaudible 00:15:53]. I’ll sleep for an hour or two and then I’ll wake up and [inaudible 00:16:03] four or five, and then I’ll sleep for another hour or two and that is the way it is.”

Others described sleep–wake cycle derangements and making modifications to bedtime routines, although not always with success: “Then, there are times, generally, I average about two hours. During the night I’m up going to the bathroom… There have been times when I’ve gotten up every 45 minutes. That’s when it’s really … I’m just out for the next day.”, and “I put a fan where it will blow on my face. I learned to put a wash rag in a Ziploc bag because I know the more you get up the less you’ll sleep. If I get to being really bad, I’ll take the cold wash rag and lay it on my neck on the side of face, facing the fan and then I will go back to sleep”.

3.4. Medical Condition

The fifth most common chronic burden pertained to the development of other medical conditions. Aerodigestive tract damage during disease and/or treatments frequently caused longer-term medical complications for patients, including recurrent pneumonia and difficulty breathing: “When we first went on the feeding tube because the aspiration pneumonia we, he was getting it twice a month…”, “I have pneumonia on a very regular basis because food goes the wrong way, if I did use food. Now I’m on a feeding tube and it still goes up and gets in my lungs. I’m just now getting over pneumonia again. I’ve been in the hospital six different times, not counting the times that I got it caught early enough that I didn’t go.” Example of difficulty breathing; “It’s a very [inaudible 00:10:16] process I have to do in order to try to open my nasal passages. I actually have to stick my fingers up in my nose and tear out that crusting in order to be able to breathe and to feel better”.

Medications for anxiety, sleep, and pain caused contraindications for some patients, to blood pressure, physical ailments, weight changes, and addictions: “I have hypothyroidism from the radiation [inaudible 00:03:29]. I’ve had several episodes of hypoglycemia during treatment. High blood pressure, high cholesterol, all the stuff that goes with it”.

Patients discussed experiencing co-occurring physical conditions, involving autoimmune, endocrine, heart, and other chronic complications: “Yeah, the steroids induced diabetes so that’s been another fight…”.

3.5. Cognition

Cognitive symptoms, involving concentration, executive functioning, and memory, were the sixth most discussed in 13 patients. Short-term memory was the most affected cognitive domain: “I don’t know. They just keep getting worse, nothing … I can remember things happen 20 years ago, but I can’t hardly remember what happened yesterday, you know what I mean?”.

Executive dysfunction was also reported, for example: “My mind’s not as sharp as it was…Sometimes I have trouble formulating a full sentence to come out of my mouth.” “I would catch myself trying to, thinking of the words, what do I need to say in my mind before. I try to grasp my words before, in a conversation, such as this”.

3.6. Interpersonal Relationships

Significant detriment to relationships was common (ranking seventh). Loss of interest in pursuing connection with others and isolation was reported: “Yeah, it’s affected all the relationships, everybody in my life. I’ve become a recluse… I’ve lost respect from my parents and my friends and family and pretty much everybody I know.”, and “It makes me feel kind of alienated from those people”.

Some patients perceived a lack of empathy from close ones, which further strained intimacy, connection, and feelings of self-worth “I think terribly. At one point my husband didn’t understand it at all. This whole thing is a nightmare. Some people they understand it but they don’t quite get it until they see me in action”, and “Most of the people I knew at the time I got sick are not in my life anymore”.

Long-term aftermath affected romantic relationships: “Sexual drive is completely gone. I had sex one time last year, none this year, which affects relationship, obviously.” and “…you haven’t had sex in a year and your wife’s upset about that”. The effects of chronic symptoms degraded relationship quality with others, sometimes contributing to divorce: “Me and my wife had been together for like eighteen years. I didn’t want to lose my wife. That happened”.

Less commonly, patients reported a transformative experience that increased social support and closeness with others: “we have a tremendous support group at Guilders club”, and “[family, friends] accept the fact that I’ve had cancer and whatever they can do to make my life easier they want to help contribute to that”.

3.7. Pain

Pain symptomatology, the eight most common burden, encompassed localized head/neck pain, muscle, joint, and general aches and pains. A majority of patients discussed acute pain of the throat, neck, tongue, and/or mouth: “This burning sensation in my throat and in my stomach, it was burning so bad. I don’t know what a heart attack feels like but when I say severe pain, the pain was so severe that I was threatening, a couple times, to go to the hospital”. This developed into a chronic condition for many patients: “I feel like I’m supposed to be healing and it seems like I’m getting worse…the pain is real, it’s very real”; another patient: “I have significant pain in my neck but it’s not unbearable pain. I can’t say that I’m more uncomfortable. It’s nothing like the pain with radiation…”.

Other localized head/neck pain constituted chronic headaches: “I’ve got a constant headache.”; another patient: “Headaches. Lots of headaches. Lots of headaches”.

Muscle and joint pains were also a recurrent physical complaint: “…the muscle spasm and the pain has come back. The muscle spasms it’s consistent now. I’m not saying every other hour. This is like every five or 10 min. I could be doing nothing, all of a sudden it’ll jump up in my neck.”, and “My neck cramps. I’ll get muscles … I call them muscle spasms. I’ll get those in there quite a bit. I’m constantly having to stretch my neck to stretch things like that out”.

For some patients, long-term physical pain had ultimately spread throughout the entire body: “I ache all over.”, “Widespread aches…” “I know my body hurts more… Some mornings, I wake up first thing in the morning, and I just sort of hurt all over. I really can’t move”.

3.8. Appetite and Food

Weight gain/loss, increased/decreased appetite, hypogeusia, dysgeusia, ageusia, and severe difficulties with eating/drinking with the ninth most common burden for patients’ quality of life: “I think the main thing … I would guess probably one of the bigger issues was my taste. Now I do have the little swallowing, that little flap that covers your windpipe probably”.

Choking and difficulty swallowing was reported by many patients: “It’s weird everybody looking at you. That’s just like when I go out and eat, I still tend to have choking spells. Today I had a little one at a restaurant. I thought half the restaurant was going to get up and give me some, what is it? The Heimlich Maneuver”.

The use of feeding tubes was also commonly discussed as causing various complications with eating and appetite, and some patients reporting that they received little if any psychoeducation with regards to these issues that would afflict them long-term: “They didn’t tell me anything about that at the time. No support, no nothing, and I didn’t realize until after four years later. Going through chemo and radiation, I was drinking all that Ensure, which is full of a lot of sugar and all that soy protein isolate and stuff, so basically what I was doing was feeding a whole colony of gut bacteria off of sugar and things. When I changed my diet last year, I reestablished some good [flauna 00:07:23], and that turned a lot of things around”.

3.9. Body Temperature

Metabolic dysregulation, such as feeling overly hot or cold, and experiencing chronic hyperhidrosis, were reported globally: “I’m telling you I got cold like a dead man… I had come in there with multiple, 3 layer clothes on. Multiple blankets wrapped around me. Get in a wheelchair and then add 2 or 3 heating blankets, I still couldn’t get warm”.

Sometimes temperature dysregulation was localized, and could be pinpointed by survivors: “…it’s the extremities. I go numb, my fingers and my toes get numb, for no reason at all. It’s warm outside, but my fingers are numb. My toes are numb. I seem to get cold quicker. A lot quicker”.

These metabolic issues effected other areas of patients’ lives: “That first summer I wore winter clothes. I had to go out around everybody and I shouldn’t really care. I don’t in a way care what anybody thinks. It is weird going out like that. It’s weird everybody looking at you”.

4. Discussion

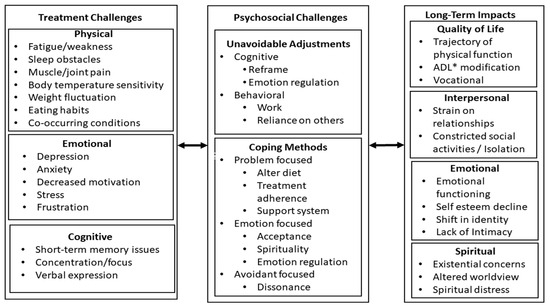

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first in-depth qualitative study to characterize chronic systemic symptoms in cancer-free head and neck cancer survivors with a significant long-term symptom burden ≥12 months from treatment completion. In sum, it highlights that (i) following treatment cessation and the eradication of the disease, a new subset of symptomatology is presented in some patients; (ii) such symptoms are frequently reported in clusters and/or deteriorate into global dysfunction, often requiring long-term care; (iii) aside from the disparate onset of interdependent symptomatology, patients may experience a fundamental transformation in self-concept that is not addressed in the clinical literature; and (iv) currently there is a lack of knowledge, data available, and clinical support for patients experiencing chronic systemic symptoms. Interestingly, the most commonly reported long-term burden pertained to mood dysfunction, alongside symptoms affecting daily activity and fatigue, comprising a primary symptom cluster. This aligns with a systematic review of symptom burden in cancer survivors among the four most common cancer types (breast, gynecological, prostrate, and rectal/colon), exposed to different treatment modalities [35]. Across the longitudinal and cross-sectional assessments, depressive symptoms, pain, and fatigue were most commonly reported and could be experienced by all cancer survivor types for >10 years following treatment/remission [35]. Our qualitative data suggest that mood disorder and interpersonal symptoms (encompassing professional remits, social connection, and intimacy) may be epiphenomenal to the significant disruptions to central physical and cognitive functionality. However, patients are better able to implement adjustments for the latter, reflected by nearly half of all the collected interview data describing some form of emotional impairment significantly eroding quality of life. The physical symptoms of head and neck cancer survivorship have been widely acknowledged/reported. For example, an international cross-sectional study [“Late toxicity and long-time quality of life in HNC survivors”, EORTC 1629 project] assessing long-term toxicities and quality of life in head and neck cancer patients, 5 years post-diagnosis, reported dry mouth and difficulty swallowing or speaking as the most frequent symptoms [36]. The study methodology was quantitative, posing one question in the patient’s case report form that asked for the two main serious effects presently being experienced. It may be that physical (dys)functionality is expected and accounted for by clinicians, whereas efficient aftercare needs to further integrate appropriate psychoeducation, emotion, social, and spiritual support. We outline these dynamics in an overarching framework as a pathway to qualitatively classify germane dimensions of the bio–psycho–social trajectory across cancer control to survivorship (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Classification framework of bio–psycho–social dimensions associated with the cancer trajectory and cancer survivorship. * ADL = activities of daily living.

One extending factor to consider with the aforementioned framework is that many of the dimensions classified are intrinsically linked to “cultural boundaries”, highlighting the importance of cultural competence in survivorship care. Patients from diverse backgrounds may have unique cultural beliefs and practices that influence their experiences of chronic symptoms, and thus the long-term impact and their preferences for ensuing care. Presently, scant data are available regarding the effects of race, ethnicity, or other cultural identities upon the survivorship experience. However, examination of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study—an extensive longitudinal research endeavor tracking more than 10,000 survivors of childhood cancers at 5 years+ in remission and their sibling controls [37]—showed that adjusting for socio-economic status did not affect health status or mortality rates across white, black, or Hispanic populations [38,39]. However, the original study reported (back in 2005) that minority cancer survivors were more likely to have lower socio-economic status, and when adjusting for income, education, and health insurance, Black survivors were less likely to report adverse mental health [37]. We surmise it is highly likely that these early data reflect cultural perspectives towards mental health and stigmas, biases in reportage, and barriers to accessing mental health cancer supportive care. As such, clinicians and healthcare providers must be sensitive to these cultural factors, read between the lines, and work collaboratively with patients (and their communities) to develop personalized care plans that respect a diverse range of cultural values and worldviews, whilst providing optimal survivorship intervention/s. This extends the entire cancer trajectory to include an inclusive/collaborative approach with patients (and their loved ones) when discussing diagnosis and treatment options, and the provision of resources/psychoeducation, so that patients are as informed as possible throughout the entire cancer process. This will facilitate a smoother transition into survivorship, ultimately ensuring unbiased care for all.

Looking forward, leveraging technology presents one potential solution to bridge gaps in care and promote inclusion for head and neck cancer survivors from diverse backgrounds and catchment areas that face unique challenges. As smartphone ownership/use becomes ubiquitous at a global scale [40], digital healthcare solutions can facilitate accessibility to culturally sensitive and personalized care for all patients, irrespective of socio-economic status or geographical location [41]. Embracing these technological advances can usher in a new era of equitable survivorship care for the cancer community as a whole, including the unique challenges experienced by the head and neck cancer population. This approach has particular promise for overcoming the aspects of social anxiety and related interpersonal issues reported here by head and neck cancer survivors, through the use of immersive interactive technologies [42]. As our qualitative study highlights, issues with swallowing, speech, facial disfigurements, and changes in appearance can have knock-on effects upon psychosocial domains, such as self-esteem and social interactions. These physical changes may lead to feelings of self-consciousness, social isolation, and even discrimination, significantly impacting quality of life. One innovative solution draws upon emerging technologies such as virtual reality and augmented reality platforms [43,44], which can provide head and neck cancer survivors with immersive experiences that empower them to navigate social interactions with confidence. Through virtual simulations, survivors can rehearse real-world scenarios, such as job interviews, social gatherings, or public speaking engagements, in a safe and supportive environment. These simulations allow survivors to overcome social challenges while honing communication skills and rebuilding their self-assurance, esteem, and self-concept. While not new per se, telemedicine and tele-rehabilitation services [45] have become more sophisticated, enabling head and neck cancer survivors to access specialized care and support remotely, improving healthcare accessibility. A scoping review of 59 studies in long-term survivors (1 year+) reported that overall cancer survivors were satisfied with telehealth interventions, although improving comprehensibility, personalization of platforms, and information accessibility were also highlighted [46]. Remote monitoring tools, wearable devices, and mobile applications also offer personalized health tracking and self-management resources, empowering survivors to actively participate in their care and monitor their progress between medical appointments, especially as they become sparser further out from cancer remission. Minimal research has been conducted on survivorship, although integration of monitoring devices for cancer patients during their radiotherapy course has shown their feasibility, patient engagement, and compliance [47]. The integration of technology into survivorship care programs will facilitate healthcare delivery of tailored interventions that address the comprehensive needs of head and neck cancer survivors, enhancing physical and psychological well-being whilst also promoting social connectedness, personal empowerment, and resilience in the face of significant adversity. Further research and investment in these technologies are essential to ensure that diversity and inclusion are central principles in the future of survivorship care.

Another underdeveloped domain highlighted from our qualitative process is that of spirituality, representing both an area of challenge as one’s worldview shifts following cancer diagnosis/treatment, and also a part of the solution as a pathway of transformation for some survivors. A focus on spiritual needs is often most prevalent in end-of-life/palliative care [48]; however, there is minimal inclusion of spiritual needs in supportive care plans for those with many years of life ahead due to the advances in cancer control. Despite having a profound impact on well-being, spiritual needs of head and neck cancer survivors are often overlooked, and are not integrated into holistic aftercare plans. Practices such as mindfulness, meditation, prayer, yoga, and expressive arts therapy (to name a few), may provide survivors with opportunities for reflection, self-expression, growth, and expansion into existential questions that can aid resilience, cognitive/emotional flexibility, feelings of connection, and overall enhancement of quality of life post cancer. Bridging this gap in supportive care acknowledges the multi-dimensional nature of cancer survivorship. It is also compatible with technological delivery, as head and neck cancer survivors can access spiritual support through apps, online groups, and potentially in the future virtual/augmented reality akin to “immersive spirituality” [42]. A recent assessment in cancer survivorship conceptualized “spiritual distress” as finding meaning/purpose in one’s life, and feeling “connections with a higher power, nature, the world, humanity, or a religion” (or lack thereof) [49]. Notably, the meaning-making process in cancer survivorship has also been highlighted previously within a stress-based framework as an important factor related to survivors’ spirituality and quality of life [50]. The authors of a recent assessment of spiritual distress suggested that clinicians need to be trained in identifying, acknowledging, and providing for spiritual distress by offering evidence-based strategies to mitigate the symptomatic impacts. A consensus forming among clinicians is that nurses on the ground (so to speak) have an optimized opportunity to assess spiritual distress, and may play a pivotal role in spiritual management for cancer survivors across their remission duration [50,51].

Limitations

Demographics were ethnically homogeneous, and further study is warranted to fully characterize the experience of late head and neck cancer survivors for ecological validity. The participants were disproportionately male, and while this discrepancy was similar to that which exists in head and neck cancer incidence rates in North America, investigation among female-identifying or gender non-binary individuals may further characterize the experience of head and neck cancer survivorship in the broader population. Moreover, we acknowledge that a sample size of 15 may be a limitation. However, it is important to highlight that qualitative research aims to explore in-depth perspectives, experiences, and nuances through a process of unpacking the richness and complexity of the data obtained from a relatively smaller number of participants, as compared to quantitative studies, for example. Finally, patients had to be able to phonate for interviews; thus, modifications needed by all head and neck cancer survivors with regard to language or communication may not be fully represented.

5. Conclusions

Head and neck cancer diagnosis and treatment are life-altering. Whilst cancer outcomes improve, acute and late treatment impacts remain detrimental to many survivors. Various coping strategies used to deal with the horrors of the disease and treatments are adopted by patients. However, long-term functional, emotional, and interpersonal alterations often serve to degrade overall quality of life. Development of targeted and multi-level treatment programs that encompass physical, psychosocial, and spiritual domains is needed to increase clinical specificity and effective, integrated, and holistic long-term head and neck cancer survivorship care.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information regarding the methodological coding system can be downloaded at https://healthbehavior.psy.vanderbilt.edu//Wulff/Wulff_CodingSystem.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2024).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: E.W.-B. and B.M.; Methodology: D.S. and K.B.; software: D.S.; formal analysis: P.S., D.S. and K.B.; investigation: P.S., E.W.-B., D.S., K.B. and B.M.; resources: D.S. and B.M.; data curation, M.D.; writing—original draft preparation: P.S. and E.W.-B.; writing—review and editing: P.S. and E.W.-B.; visualization: P.S.; project administration: E.W.-B., D.S. and K.B.; funding acquisition: B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Ingram Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Vanderbilt University Medical Center (protocol #141229; approved: 20 August 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Much appreciation and gratitude to all the patients who shared their experiences of their symptoms for the purposes of this qualitative study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, except Dr. Wulff-Burchfield, who would like to mention that she is a consultant/advisor for Astellas, Aveo Oncology, BMS, Exelixis, Janssen, and Pfizer, and has stock ownership in Nektar.

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forastiere, A.A.; Trotti, A.; Pfister, D.G.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck cancer: Recent advances and new standards of care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 2603–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlader, N.; Noone, A.M.; Krapcho, M.; Miller, D.; Brest, A.; Yu, M.; Ruhl, J.; Tatalovich, Z.; Mariotto, A.; Lewis, D.R.; et al. (Eds.) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2018; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, K.; Ristovski-Slijepcevic, S. Cancer Survivorship: Why Labels Matter. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, T.; Enokida, T.; Wakasugi, T.; Zenda, S.; Motegi, A.; Arahira, S.; Akimoto, T.; Tahara, M. Impact of prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement on treatment tolerance in head and neck cancer patients treated with cetuximab plus radiation. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 46, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.F.; Rau, K.M.; Shao, Y.Y.; Yen, C.J.; Wu, M.F.; Chen, J.S.; Chang, C.S.; Yeh, S.P.; Chiou, T.J.; Hsieh, R.K.; et al. Patients with head and neck cancer may need more intensive pain management to maintain daily functioning: A multi-center study. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, S.G.; Pai, M.S.; George, L.S. Quality of life of patients with head and neck cancer: A mixed method study. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2019, 15, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringash, J. Survivorship and Quality of Life in Head and Neck Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3322–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, M.; Habib, L.A.; Morrison, M.; Yang, J.W.; Li, X.J.; Lin, S.; Zeitouni, A.; Payne, R.; MacDonald, C.; Mlynarek, A.; et al. Head and neck cancer patients want us to support them psychologically in the posttreatment period: Survey results. Palliat. Support. Care 2014, 12, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotti, A.; Pajak, T.F.; Gwede, C.K.; Paulus, R.; Cooper, J.; Forastiere, A.; Ridge, J.A.; Watkins-Bruner, D.; Garden, A.S.; Ang, K.K.; et al. TAME: Development of a new method for summarising adverse events of cancer treatment by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Lancet Oncol. 2007, 8, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff-Burchfield, E.; Dietrich, M.S.; Ridner, S.; Murphy, B.A. Late systemic symptoms in head and neck cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2893–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.A.; Ridner, S.; Wells, N.; Dietrich, M. Quality of life research in head and neck cancer: A review of the current state of the science. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007, 62, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvao-Moreira, L.V.; da Cruz, M.C.F.N. Dental demineralization, radiation caries and oral microbiota in patients with head and neck cancer. Oral. Oncol. 2015, 51, E89–E90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Jackson, L.; Epstein, J.B.; Migliorati, C.A.; Murphy, B.A. Dental demineralization and caries in patients with head and neck cancer. Oral. Oncol. 2015, 51, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Ridner, S.H.; Dietrich, M.S.; Wells, N.; Wallston, K.A.; Sinard, R.J.; Cmelak, A.J.; Murphy, B.A. Prevalence of Secondary Lymphedema in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2012, 43, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machtay, M.; Moughan, J.; Trotti, A.; Garden, A.S.; Weber, R.S.; Cooper, J.S.; Forastiere, A.; Ang, K.K. Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: An RTOG analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3582–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.D.; Johnson, J.T.; Nilsen, M.L. Pain in Head and Neck Cancer Survivors: Prevalence, Predictors, and Quality-of-Life Impact. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2018, 159, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, K.S.; Reddy, S.K.; Lee, M.C.; Patt, R.B. Pain and loss of function in head and neck cancer survivors. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1999, 18, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulff-Burchfield, E.M.; Dietrich, M.S.; Murphy, B.A. Late systemic symptom (SS) frequency in head and neck cancer (HNC) survivors as measured by the Vanderbilt Head and Neck Symptom Survey—General Symptoms Subscale (GSS). J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.A.; Beaumont, J.L.; Isitt, J.; Garden, A.S.; Gwede, C.K.; Trotti, A.M.; Meredith, R.F.; Epstein, J.B.; Le, Q.T.; Brizel, D.M.; et al. Mucositis-related morbidity and resource utilization in head and neck cancer patients receiving radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2009, 38, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payakachat, N.; Ounpraseuth, S.; Suen, J.Y. Late complications and long-term quality of life for survivors (>5 years) with history of head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2013, 35, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonne, V.; Otz, J.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Dissaux, G.; Lucia, F.; Leclere, J.C.; Pradier, O.; Schick, U. Radiotherapy mucositis in head and neck cancer: Prevention by low-energy surface laser. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 12, e838–e845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Meng, L.; Dong, L.; Jiang, X. Status of Treatment and Prophylaxis for Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 642575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Murphy, B.A. Lymphedema self-care in patients with head and neck cancer: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 4961–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridner, S.H.; Dietrich, M.S.; Deng, J.; Ettema, S.L.; Murphy, B. Advanced pneumatic compression for treatment of lymphedema of the head and neck: A randomized wait-list controlled trial. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davy, C.; Heathcote, S. A systematic review of interventions to mitigate radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2187–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.A.; Wulff-Burchfield, E.; Ghiam, M.; Bond, S.M.; Deng, J. Chronic Systemic Symptoms in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2019, 2019, lgz004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.; Hanlon, A.; Zhang, Q.; Ang, K.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Nguyen-Tan, P.F.; Kim, H.; Movsas, B.; Bruner, D.W. Symptom clusters in patients with head and neck cancer receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Oral. Oncol. 2013, 49, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomi, M.; Patsias, A.; Posner, M.; Sikora, A. The Role of Inflammation in Head and Neck Cancer. In Inflammation and Cancer; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Aggarwal, B.B., Sung, B., Gupta, S.C., Eds.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Vichaya, E.G.; Chiu, G.S.; Krukowski, K.; Lacourt, T.E.; Kavelaars, A.; Dantzer, R.; Heijnen, C.J.; Walker, A.K. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced behavioral toxicities. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.F.; Watkins, L.R. Immune-to-central nervous system communication and its role in modulating pain and cognition: Implications for cancer and cancer treatment. Brain Behav. Immun. 2003, 17 (Suppl. 1), S125–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.N.; Dantzer, R.; Langley, K.E.; Bennett, G.J.; Dougherty, P.M.; Dunn, A.J.; Meyers, C.A.; Miller, A.H.; Payne, R.; Reuben, J.M.; et al. A cytokine-based neuroimmunologic mechanism of cancer-related symptoms. Neuroimmunomodulation 2004, 11, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, P.L.A.; Song, A.K.; Mohr, E.M.; Rogers, B.P.; Peterson, T.E.; Murphy, B.A. Increased microglia activation in late non-central nervous system cancer survivors links to chronic systemic symptomatology. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023, 44, 6001–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, C.; Hansen, J.; Moskowitz, M.; Todd, B.; Feuerstein, M. It’s Not over When it’s Over: Long-Term Symptoms in Cancer Survivors—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2010, 40, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.J.; Amdal, C.D.; Bjordal, K.; Astrup, G.L.; Herlofson, B.B.; Duprez, F.; Gama, R.R.; Jacinto, A.; Hammerlid, E.; Scricciolo, M.; et al. Serious Long-Term Effects of Head and Neck Cancer from the Survivors’ Point of View. Healthcare 2023, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robison, L.L.; Green, D.M.; Hudson, M.; Meadows, A.T.; Mertens, A.C.; Packer, R.J.; Sklar, C.A.; Strong, L.C.; Yasui, Y.; Zeltzer, L.K. Long-term outcomes of adult survivors of childhood cancer: Results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 2005, 104, 2557–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellino, S.M.; Casillas, J.; Hudson, M.M.; Mertens, A.C.; Whitton, J.; Brooks, S.L.; Zeltzer, L.K.; Ablin, A.; Castleberry, R.; Hobbie, W.; et al. Minority adult survivors of childhood cancer: A comparison of long-term outcomes, health care utilization, and health-related behaviors from the childhood cancer survivor study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 6499–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, K.D.; Syrjala, K.L.; Andrykowski, M.A. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 2008, 112, 2577–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, F. More Phones than People. Statistica: Mobile Communications. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/4022/mobile-subscriptions-and-world-population/ (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Areias, A.C.; Molinos, M.; Moulder, R.G.; Janela, D.; Scheer, J.K.; Bento, V.; Yanamadala, V.; Cohen, S.P.; Correia, F.D.; Costa, F. The potential of multimodal digital care program in addressing healthcare inequities in musculoskeletal pain management. Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, P.L.A. Welcoming the “metaverse” in integrative and complementary medicine: Introductory overview. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 2023, 8, 046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melillo, A.; Chirico, A.; De Pietro, G.; Gallo, L.; Caggianese, G.; Barone, D.; De Laurentiis, M.; Giordano, A. Virtual Reality Rehabilitation Systems for Cancer Survivors: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Cancers 2022, 14, 3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buche, H.; Michel, A.; Blanc, N. Use of virtual reality in oncology: From the state of the art to an integrative model. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 3, 894162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, K.M.; Turner, K.L.; Siwik, C.; Gonzalez, B.D.; Upasani, R.; Glazer, J.V.; Ferguson, R.J.; Joshua, C.; Low, C.A. Digital health and telehealth in cancer care: A scoping review of reviews. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e316–e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irurita-Morales, P.; Soto-Ruiz, N.; San Martín-Rodríguez, L.; Escalada-Hernández, P.; García-Vivar, C. Use of telehealth among cancer survivors: A scoping review. Telemed. e-Health 2023, 29, 956–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahidi, R.; Mintz, R.; Agabalogun, T.; Mayer, L.; Badiyan, S.; Spraker, M.B. Remote symptom monitoring of patients with cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Cureus 2022, 14, e29734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.M. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23 (Suppl. 3), 11149–11155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.L. Spirituality and meaning making in cancer survivorship. In The Psychology of Meaning; Markman, K.D., Proulx, T., Lindberg, M.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, T.S.; Browning, K.; Vo, J.B.; Meadows, R.J.; Paxton, R.J. CE: Assessing and Managing Spiritual Distress in Cancer Survivorship. Am. J. Nurs. 2020, 120, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachon, M.L.S. Meaning, spirituality, and wellness in cancer survivors. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2008, 24, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).