Prospective, Observational Study of Aflibercept Use in Combination with FOLFIRI in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Real-World Effectiveness Study

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Assessment

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Treatment Exposure

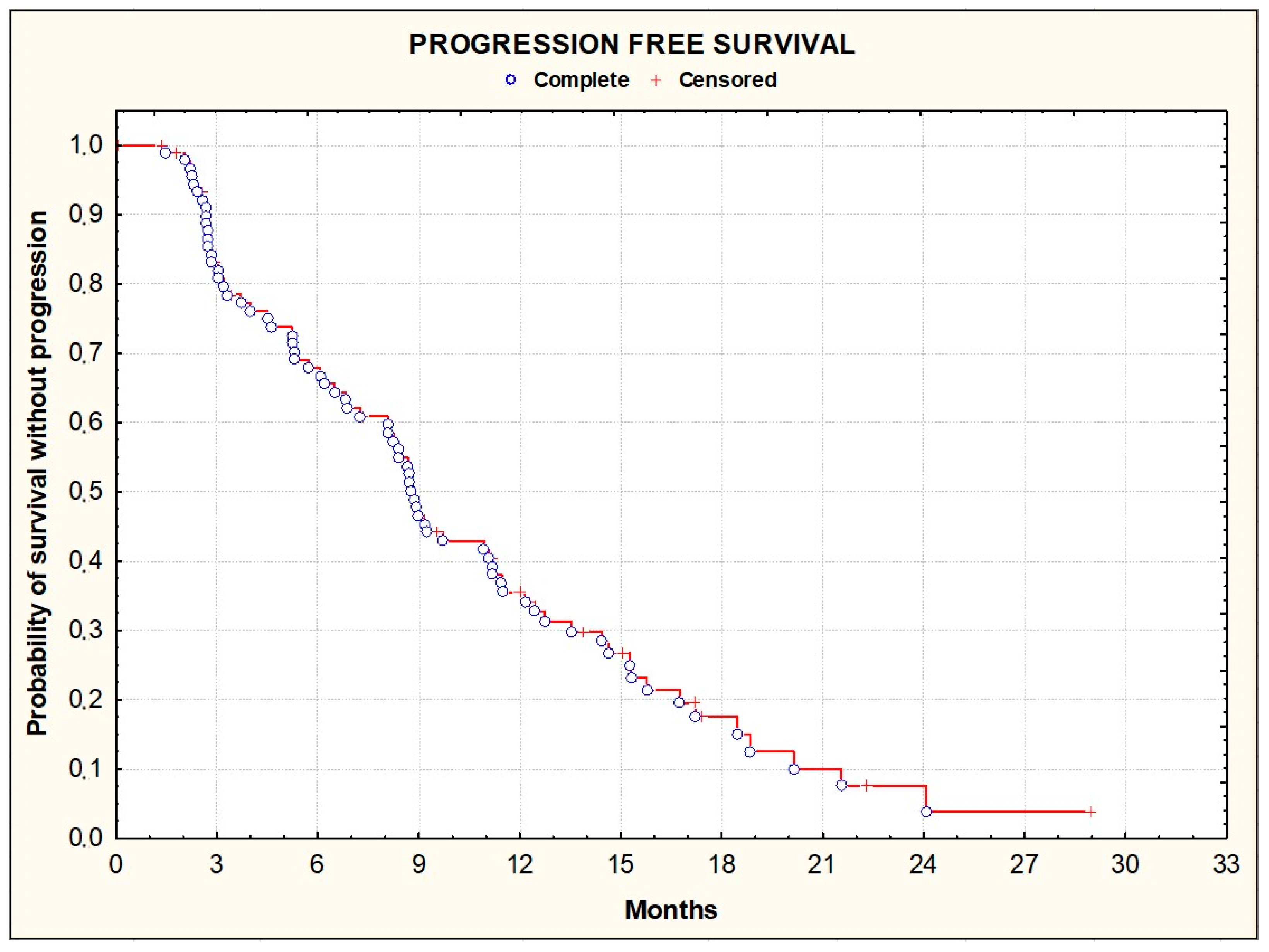

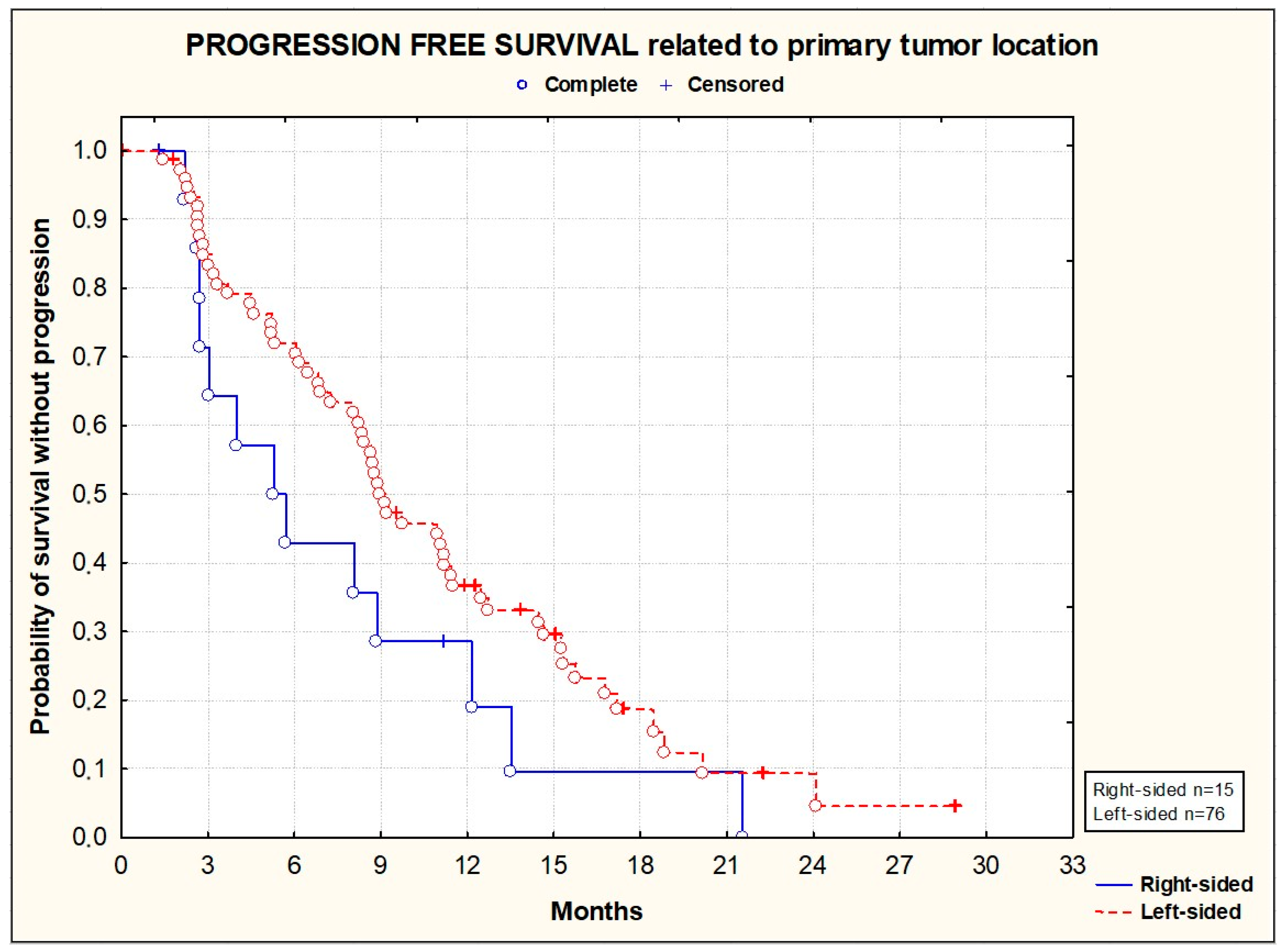

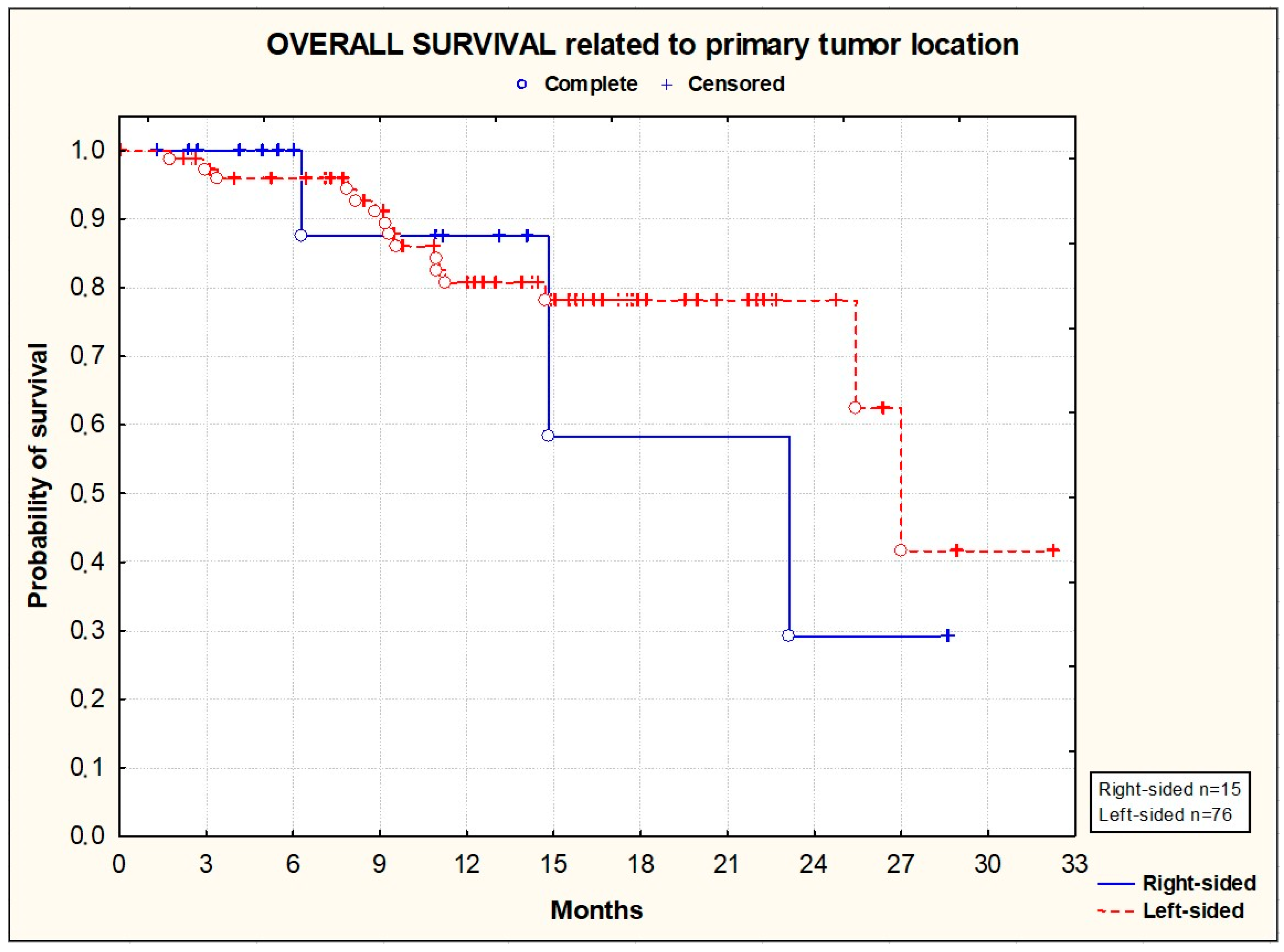

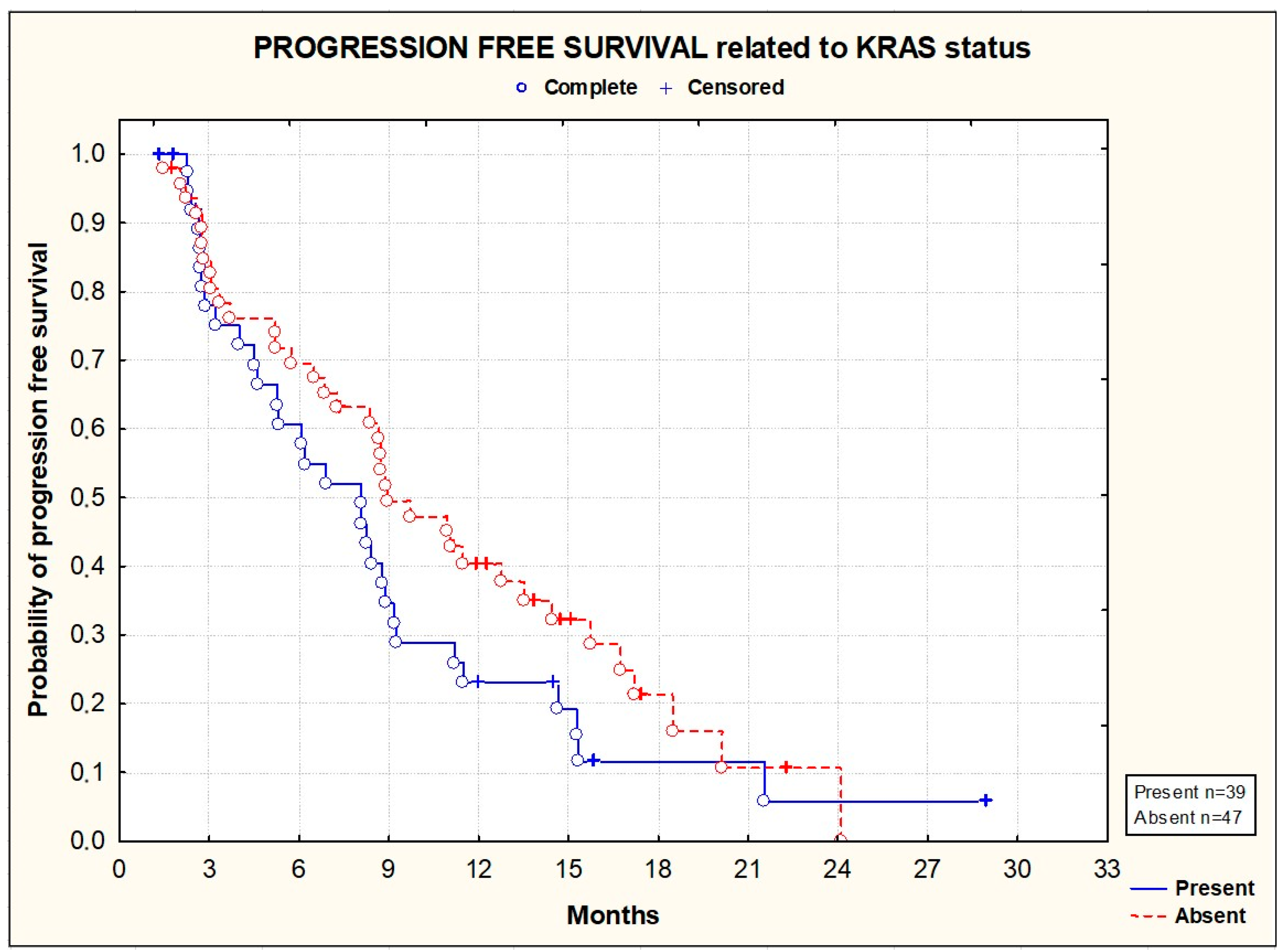

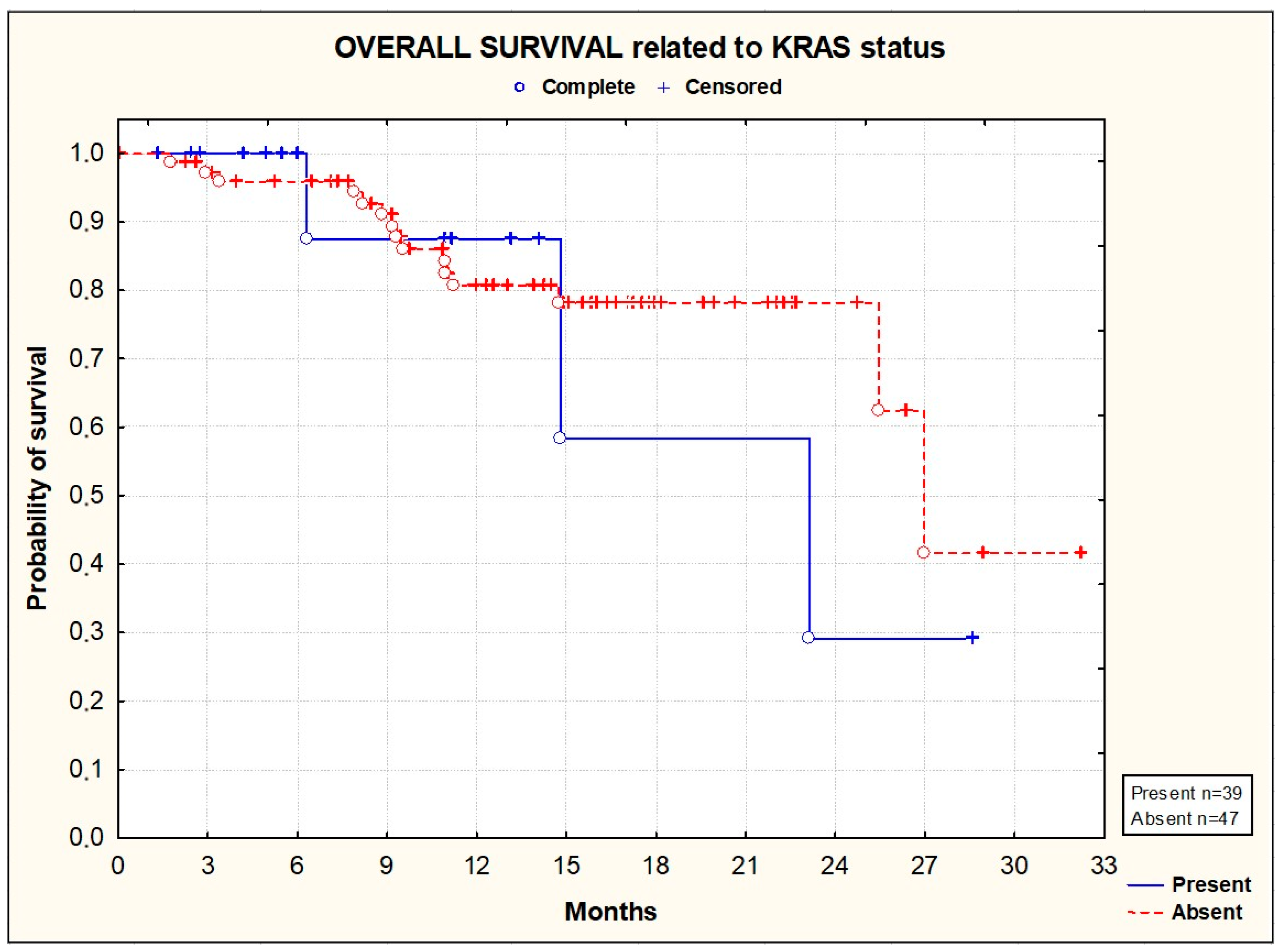

3.2. Efficacy

3.3. Safety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santucci, C.; Mignozzi, S.; Malvezzi, M.; Boffetta, P.; Collatuzzo, G.; Levi, F.; La Vecchia, C.; Negri, E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2024 with focus on colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didkowska, J.; Wojciechowska, U.; Michalek, I.M.; Caetano Dos Santos, F.L. Cancer incidence and mortality in Poland in 2019. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, A.C.; Dixon, S.W.; White, P.C.; Williams, A.C.; Thomas, M.G.; Messenger, D.E. Demographic trends in the incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer: A population-based study. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Andrea Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2018. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018/index.html (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- De Gramont, A.; Bosset, J.F.; Milan, C.; Rougier, P.; Bouché, O.; Etienne, P.-L.; Morvan, F.; Lauvet, C.; Guillot, T.; Francois, E.; et al. Randomized trial comparing monthly low-dose leucovorin and fluorouracil bolus with bimonthly high-dose leucovorin and fluorouracil bolus plus continuous infusion for advanced colorectal cancer: A French intergroup study. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Hoff, P.M.; Harper, P.; Bukowski, R.M.; Cunningham, D.; Dufour, P.; Graeven, U.; Lokich, J.; Madajewicz, J.S.; Maroun, A.; et al. Oral capecitabine vs intravenous 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin: Integrated efficacy data and novel analyses from two large, randomised, phase III trials. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 90, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J.; Clarke, S.; Díaz-Rubio, E.; Scheithauer, W.; Figer, A.; Wong, R.; Koski, S.; Lichinitser, M.; Yang, T.-S.; Rivera, F.; et al. Randomized phase III study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil/folinic acid plus oxaliplatin as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2006–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gramont, A.; Figer, A.; Seymour, M.; Homerin, M.; Hmissi, A.; Cassidy, J.; Boni, C.; Cortes-Funes, H.; Cervantes, A.; Freyer, G.; et al. Leucovorin and Fluorouracil With or Without Oxaliplatin as First-Line Treatment in Advanced Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 5080–5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douillard, J.Y.; Cunningham, D.; Roth, A.D.; Navarro, M.; James, R.D.; Karasek, P.; Jandik, P.; Iveson, T.; Carmichael, J.; Alakl, M.; et al. Irinotecan combined with fluorouracil compared with fluorouracil alone as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: A multicentre randomized trial. Lancet 2000, 355, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douillard, J.-Y.; Oliner, K.S.; Siena, S.; Tabernero, J.; Burkes, R.; Barugel, M.; Humblet, Y.; Bodoky, G.; Cunningham, D.; Jassem, J.; et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokemeyer, C.; Köhne, C.-H.; Ciardiello, F.; Lenz, H.-J.; Heinemann, V.; Klinkhardt, U.; Beier, F.; Duecker, K.; van Krieken, J.H.; Tejpar, S. FOLFOX4 plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Lenz, H.-J.; Köhne, C.-H.; Heinemann, V.; Tejpar, S.; Melezínek, I.; Beier, F.; Stroh, C.; Rougier, P.; van Krieken, J.H.; et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, T.; Hooda, N.; Younan, D.; Muro, K.; Shitara, K.; Heinemann, V.; O’Neil, H.B.; Rivera Herrero, F.; Peeters, M.; Soeda, J.; et al. A meta-analysis of efficacy and safety data from head-to-head first-line trials of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors versus bevacizumab in adult patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer by sidedness. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 202, 113975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournigand, C.; André, T.; Achille, E.; Lledo, G.; Flesh, M.; Mery-Mignard, D.; Quinaux, E.; Couteau, C.; Buyse, M.; Ganem, G.; et al. FOLFIRI Followed by FOLFOX6 or the Reverse Sequence in Advanced Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized GERCOR Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3469–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennouna, J.; Sastre, J.; Arnold, D.; Österlund, P.; Greil, R.; Van Cutsem, E.; von Moos, R.; Viéitez, J.M.; Bouché, O.; Borg, C.; et al. Continuation of Bevacizumab after First Progression in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (ML18147): A Randomised Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabernero, J.; Yoshino, T.; Cohn, A.L.; Obermannova, R.; Bodoky, G.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Portnoy, D.C.; Van Cutsem, E.; Grothey, A.; et al. Ramucirumab versus Placebo in Combination with Second-Line FOLFIRI in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Carcinoma That Progressed during or after First-Line Therapy with Bevacizumab, Oxaliplatin, and a Fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Multicentre, Phase 3 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Roselló, S.; Arnold, D.; Normanno, N.; Taïeb, J.; Seligmann, J.; De Baere, T.; Osterlund, P.; Yoshino, T.; et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holash, J.; Davis, S.; Papadopoulos, N.; Croll, S.D.; Ho, L.; Russell, M.; Boland, P.; Leidich, R.; Hylton, D.; Burovaet, E.; et al. VEGF Trap: A VEGF blocker with potent antitumor effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11393–11398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, N.; Martin, J.; Ruan, J.; Rafique, A.; Rosconi, M.P.; Shi, E.; Pyles, E.A.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Stahl, N.; Wiegandet, S.J.; et al. Binding and neutralization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and related ligands by VEGF Trap, ranibizumab and bevacizumab. Angiogenesis 2012, 15, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiron, M.; Bagley, R.G.; Pollard, J.; Mankoo, P.K.; Henry, C.; Vincent, L.; Geslin, C.; Baltes, N.; Bergstrom, D.A. Differential Antitumor Activity of Aflibercept and Bevacizumab in Patient-Derived Xenograft Models of Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Y.Y.; McKeage, K. Aflibercept: A Review in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Drugs 2015, 75, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Tabernero, J.; Lakomy, R.; Prenen, H.; Prausova, J.; Macarulla, T.; Ruff, P.; van Hazel, G.A.; Moiseyenko, V.; Ferry, D.; et al. Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3499–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, J.; Van Cutsem, E.; Lakomý, R.; Prausová, J.; Ruff, P.; van Hazel, G.A.; Moiseyenko, V.M.; Ferry, D.R.; McKendrick, J.J.; Soussan-Lazard, K.; et al. Aflibercept versus placebo in combination with fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan in the treatment of previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: Prespecified subgroup analyses from the VELOUR trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Joulain, F.; Hoff, P.M.; Mitchell, E.; Ruff, P.; Lakomý, R.; Prausová, J.; Moiseyenko, V.M.; van Hazel, G.; Cunningham, D.; et al. Aflibercept Plus FOLFIRI vs. Placebo Plus FOLFIRI in Second-Line Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Post Hoc Analysis of Survival from the Phase III VELOUR Study Subsequent to Exclusion of Patients who had Recurrence During or Within 6 Months of Completing Adjuvant Oxaliplatin-Based Therapy. Target. Oncol. 2016, 11, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, P.; Ferry, D.R.; Lakomy, R.; Prausova, J.; Van Hazel, G.A.; Hoff, P.M.; Cunningham, D.; Arnold, D.; Schmoll, H.J.; Moiseyenko, V.M.; et al. Time course of safety and efficacy of aflibercept in combination with FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who progressed on previous oxaliplatin-based therapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Pearson, S.-A.; Simes, R.J.; Chua, B.H. Harnessing Real-World Evidence to Advance Cancer Research. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 1844–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirapati, P.; Pomella, V.; Vandenbosch, B.; Kerr, P.; Maiello, E.; Jeffery, G.M.; Curca, R.-O.; Karthaus, M.; Bridgewater, J.; Mihailov, A.; et al. Velour trial biomarkers update: Impact of RAS, BRAF, and sidedness on aflibercept activity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 18 (Suppl. 3), III151–III152. [Google Scholar]

- Hofheinz, R.D.; Anchisi, S.; Grunberger, B.; Zahn, M.O.; Geffriaud-Ricouard, C.; Gueldner, M.; Windemuth-Kieselbach, C.H.; Pederiva, S.; Bohanes, P.; Scholten, F.; et al. Real-World Evaluation of Quality of Life, Effectiveness and Safety of Aflibercept Plus FOLFIRI in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. The prospective QoLiTrap Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Overall Population (n = 93) |

|---|---|

| Males, n (%) | 55 (59.1%) |

| Median age (range) | 62 (29–81) |

| Primary tumor, n (%) | |

| Right-sided | 15 (16.1) |

| Resected | 24 (32.0) |

| Metastases, n (%) | |

| Synchronous | 60 (64.5) |

| Prior resection of metastases | 24 (32.0) |

| Metastatic sites at inclusion, n (%) | |

| Liver | 66 (71.0) |

| Lung | 46 (49.5) |

| Lymph node | 38 (40.9) |

| Peritoneum | 11 (11.8) |

| Other | 26 (28.3) |

| Liver-only disease | 20 (21.7) |

| RAS/BRAF status, n (%) | |

| KRAS | 39 (42%) |

| NRAS | 3 (3%) |

| BRAF | 4 (4%) |

| Prior therapies, n (%) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 39 (49.4) |

| Radiotherapy | 22 (23.7) |

| Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy | 93 (100) |

| EGFR inhibitors | 23 (24.7%) |

| ECOG performance status at inclusion | |

| 1 | 51 (54.8%) |

| 2 | 42 (45.2%) |

| Modalities of Treatment with Aflibercept + FOLFIRI | |

|---|---|

| Duration of treatment, months | n = 93 |

| Mean ± SD | 6.3 ± 5.0 |

| Range | 0–22.8 |

| Median | 5.0 |

| Q1–Q3 | 2.4–8.5 |

| Number of cycles | n = 93 |

| Mean ± SD | 11.5 ± 8.2 |

| Range | 1.0–38.0 |

| Median | 10 |

| Q1–Q3 | 5.0–15.0 |

| Aflibercept treatment | |

| Dose administered per cycle, mg/kg | n = 93 |

| Mean ± SD | 3.99 ± 0.1 |

| Range | 2.99–4.32 |

| Median | 4.0 |

| Q1–Q3 | 4.0–4.0 |

| Total dose administered per cycle, mg | n = 93 |

| Mean ± SD | 314.9 ± 74.2 |

| Range | 194–568 |

| Median | 300 |

| Q1–Q3 | 256–368 |

| Total (cumulative) dose administered, mg | n = 93 |

| Mean ± SD | 3427 ± 2774 |

| Range | 284–4336 |

| Median | 3124 |

| Q1–Q3 | 1400–4336 |

| Fluorouracil treatment | |

| Total dose administered per cycle, mg | n = 93 |

| Mean ± SD | 4451 ± 1433 |

| Range | 612–7248 |

| Median | 4816 |

| Q1–Q3 | 3870–5516 |

| Irinotecan treatment | |

| Total dose administered per cycle, mg | n = 93 |

| Mean ± SD | 331.7 ± 44.5 |

| Range | 200.0–466.0 |

| Median | 338.0 |

| Q1–Q3 | 306.0–360.0 |

| Folinic acid treatment | |

| Total dose administered per cycle, mg | n = 93 |

| Mean ± SD | 503.3 ± 227.9 |

| Range | 154.7–1035.0 |

| Median | 400.0 |

| Q1–Q3 | 340.0–730.0 |

| Patients, N (%) | Safety Population (N = 93) |

|---|---|

| N of patients reporting AEs of any grade | 71 (76%) |

| N of patients reporting grade ≥ 3 AEs | 32 (34%) |

| N of patients reporting serious AEs | 13 (14%) |

| N of patients reporting AEs leading to Tx discontinuation | 26 (28%) |

| N of patients reporting AEs leading to death | 1 (1%) |

| N of Patients with Adverse Events | All Grade N (%) | G 1–2 N (%) | G 3–4 N (%) | G 5 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N of patients reporting any adverse event | 71 (76%) | 62 (67%) | 32 (34%) | 1 (1%) |

| Most common adverse events | ||||

| Diarrhea | 23 (25%) | 19 (20%) | 4 (4%) | - |

| Hypertension ** | 19 (20%) | 11 (12%) | 7 (8%) | - |

| Asthenia | 17 (18%) | 15 (16%) | 2 (2%) | - |

| Stomatitis | 14 (15%) | 10 (11%) | 4 (4%) | - |

| Abdominal pain, upper | 12 (13%) | 11 (12%) | 1 (1%) | - |

| Decreased appetite ** | 8 (9%) | 7 (8%) | - | - |

| Upper airway infection | 8 (9%) | 8 (9%) | - | - |

| Vomiting | 6 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 1 (1%) | - |

| Constipation | 6 (6%) | 6 (6%) | - | - |

| Weight decrease | 6 (6%) | 6 (6%) | - | - |

| Dysphonia | 6 (6%) | 6 (6%) | - | - |

| Epilation | 6 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 1 (1%) | - |

| Nausea | 5 (5%) | 5 (5%) | - | - |

| Headache | 5 (5%) | 5 (5%) | - | - |

| Chest pain | 5 (5%) | 5 (5%) | - | - |

| Tachycardia | 4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | - | - |

| Epistaxis | 4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | - | - |

| Esophageal candidiasis | 4 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | - |

| Erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | - | - |

| Mouth ulceration | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | - | - |

| Pyrexia | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | - | - |

| Polyneuropathy | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | - | - |

| Joint swelling | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | - | - |

| Acute sinusitis | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | - | - |

| Skin lesions | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | - | - |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| Neutropenia | 29 (31%) | 14 (15%) | 15 (16%) | - |

| Proteinuria | 15 (16%) | 12 (13%) | 3 (3%) | - |

| Thrombocytopenia | 12 (13%) | 12 (13%) | - | - |

| Leukopenia | 9 (10%) | 8 (9%) | 1 (1%) | - |

| Hematuria | 8 (9%) | 8 (9%) | - | - |

| Alkaline phosphatase increase | 6 (6%) | 6 (6%) | - | - |

| Anemia of malignant disease | 5 (5%) | 4 (4%) | 1 (1%) | - |

| ALAT increase | 5 (5%) | 5 (5%) | - | - |

| ASAT increase | 5 (5%) | 5 (5%) | - | - |

| Glutamyl transferase increased | 5 (5%) | 5 (5%) | - | - |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 5 (5%) | 5 (5%) | - | - |

| Hypokalemia | 4 (4%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | - |

| Hyponatremia | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Durbajło, A.; Świeżyński, M.; Ziemba, B.; Starzyczny-Słota, D.; Samborska-Plewicka, M.; Cencelewicz-Lesikow, A.; Chrzanowska-Kapica, A.; Dobrzyńska-Rutkowska, A.; Drab-Mazur, I.; Kulma-Kreft, M.; et al. Prospective, Observational Study of Aflibercept Use in Combination with FOLFIRI in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Real-World Effectiveness Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 1992. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16111992

Durbajło A, Świeżyński M, Ziemba B, Starzyczny-Słota D, Samborska-Plewicka M, Cencelewicz-Lesikow A, Chrzanowska-Kapica A, Dobrzyńska-Rutkowska A, Drab-Mazur I, Kulma-Kreft M, et al. Prospective, Observational Study of Aflibercept Use in Combination with FOLFIRI in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Real-World Effectiveness Study. Cancers. 2024; 16(11):1992. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16111992

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurbajło, Agnieszka, Marcin Świeżyński, Beata Ziemba, Danuta Starzyczny-Słota, Marzena Samborska-Plewicka, Anna Cencelewicz-Lesikow, Agata Chrzanowska-Kapica, Aneta Dobrzyńska-Rutkowska, Iwona Drab-Mazur, Monika Kulma-Kreft, and et al. 2024. "Prospective, Observational Study of Aflibercept Use in Combination with FOLFIRI in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Real-World Effectiveness Study" Cancers 16, no. 11: 1992. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16111992

APA StyleDurbajło, A., Świeżyński, M., Ziemba, B., Starzyczny-Słota, D., Samborska-Plewicka, M., Cencelewicz-Lesikow, A., Chrzanowska-Kapica, A., Dobrzyńska-Rutkowska, A., Drab-Mazur, I., Kulma-Kreft, M., Sikora-Skrabaka, M., Matuszewska, E., Foszczyńska-Kłoda, M., Lewandowski, T., Słomian, G., Ostrowska-Cichocka, K., Chmielowska, E., Wiśniowski, R., Twardosz, A., ... Wyrwicz, L. (2024). Prospective, Observational Study of Aflibercept Use in Combination with FOLFIRI in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Real-World Effectiveness Study. Cancers, 16(11), 1992. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16111992