Social Support in a Cancer Patient-Informal Caregiver Dyad: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Process and Sources

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

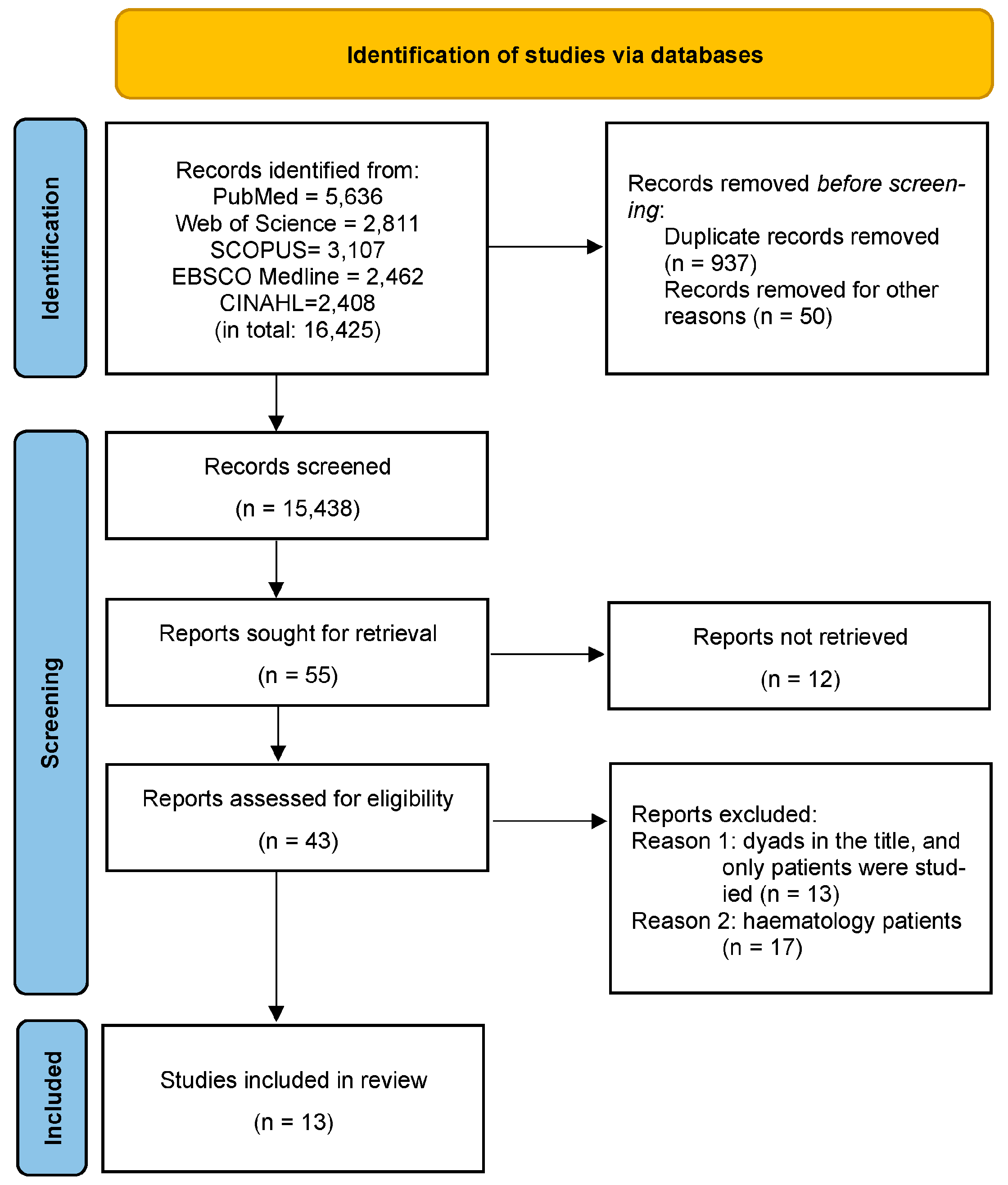

2.4. Selection Flow

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ReferencesTraa, M.J.; De Vries, J.; Bodenmann, G.; Den Oudsten, B.L. Dyadic Coping and Relationship Functioning in Couples Coping with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, H.; Schuler, M.; Richard, M.; Heckl, U.; Weis, J.; Küffner, R. Effects of Psycho-Oncologic Interventions on Emotional Distress and Quality of Life in Adult Patients with Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JCO 2013, 31, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Loke, A.Y. A Systematic Review of Spousal Couple-Based Intervention Studies for Couples Coping with Cancer: Direction for the Development of Interventions: Couple-Based Intervention for Couples Coping with Cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2014, 23, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, T.; Levesque, J.V.; Lambert, S.D.; Kelly, B. A Qualitative Investigation of Health Care Professionals’, Patients’ and Partners’ Views on Psychosocial Issues and Related Interventions for Couples Coping with Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.D.; Girgis, A.; Turner, J.; Regan, T.; Candler, H.; Britton, B.; Chambers, S.; Lawsin, C.; Kayser, K. “You Need Something like This to Give You Guidelines on What to Do”: Patients’ and Partners’ Use and Perceptions of a Self-Directed Coping Skills Training Resource. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 3451–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesing, S.; Rosenwax, L.; McNamara, B. A Dyadic Approach to Understanding the Impact of Breast Cancer on Relationships between Partners during Early Survivorship. BMC Women’s Health 2016, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.R.; Raji, D.; Olaniran, M.; Alick, C.; Nichols, D.; Allicock, M. A Systematic Scoping Review of Post-Treatment Lifestyle Interventions for Adult Cancer Survivors and Family Members. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 16, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoktunowicz, E.; Cieslak, R.; Żukowska, K. Role of Perceived Social Support in the Context of Occupational Stress and Work Engagement. Psychol. Stud. 2014, 52, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquati, C.; Hibbard, J.H.; Miller-Sonet, E.; Zhang, A.; Ionescu, E. Patient Activation and Treatment Decision-Making in the Context of Cancer: Examining the Contribution of Informal Caregivers’ Involvement. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 16, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasek, M.; Dębska, G.; Wojtyna, E. Perceived Social Support and the Sense of Coherence in Patient–Caregiver Dyad versus Acceptance of Illness in Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4985–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, G.P.; Dalla Riva, M.S.; Orrù, L.; Pinto, E. How to Intervene in the Health Management of the Oncological Patient and of Their Caregiver? A Narrative Review in the Psycho-Oncology Field. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, F.D. Effects of Social Support on Physical Activity, Self-Efficacy, and Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors and Their Caregivers. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2013, 40, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, K.G. Correlates of Self-Rated Attachment in Patients with Cancer and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Correlates of Self-Rated Attachment and Psychosocial Variables. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Chirico, I.; Ottoboni, G.; Chattat, R. Relationship Dynamics among Couples Dealing with Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apply PCC—Scoping Reviews—Guides at University of South Australia. Available online: https://guides.library.unisa.edu.au/ScopingReviews/ApplyPCC (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- PROSPERO. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Bramer, W.M.; De Jonge, G.B.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Mast, F.; Kleijnen, J. A Systematic Approach to Searching: An Efficient and Complete Method to Develop Literature Searches. JMLA 2018, 106, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D. Handsearching Still a Valuable Element of the Systematic Review: Does Handsearching Identify More Randomised Controlled Trials than Electronic Searching? Evid. Based Dent. 2008, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayik, D.B.; Saritas, S.C. Determination of the Relationship between Social Support and Quality of Life in Oncology Patients and Caregivers. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2022, 15, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Boeding, S.E.; Pukay-Martin, N.D.; Baucom, D.H.; Porter, L.S.; Kirby, J.S.; Gremore, T.M.; Keefe, F.J. Couples and Breast Cancer: Women’s Mood and Partners’ Marital Satisfaction Predicting Support Perception. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-J.; Wang, Q.-L.; Li, H.-P.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, S.-S.; Zhou, M.-K. Family Resilience, Perceived Social Support, and Individual Resilience in Cancer Couples: Analysis Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Mediation Model. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 52, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dębska, G.; Pasek, M.; Wojtyna, E. Does Anybody Support the Supporters? Social Support in the Cancer Patient-Caregiver Dyad. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Rev. 2017, 19, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldzweig, G.; Baider, L.; Andritsch, E.; Rottenberg, Y. Hope and Social Support in Elderly Patients with Cancer and Their Partners: An Actor–Partner Interdependence Model. Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 2801–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson-Ohayon, I.; Goldzweig, G.; Dorfman, C.; Uziely, B. Hope and Social Support Utilisation among Different Age Groups of Women with Breast Cancer and Their Spouses. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 1303–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, A.; An, J.Y. The Moderating Role of Social Support on Depression and Anxiety for Gastric Cancer Patients and Their Family Caregivers. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, E.; Levesque, J.V.; Lambert, S.; Girgis, A. The “Sphere of Care”: A Qualitative Study of Colorectal Cancer Patient and Caregiver Experiences of Support within the Cancer Treatment Setting. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasek, M.; Suchocka, L. A Model of Social Support for a Patient-Informal Caregiver Dyad. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 4470366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterba, K.R.; Zapka, J.; Armeson, K.E.; Shirai, K.; Buchanan, A.; Day, T.A.; Alberg, A.J. Physical and Emotional Well-Being and Support in Newly Diagnosed Head and Neck Cancer Patient-Caregiver Dyads. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2017, 35, 646–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surucu, S.G.; Ozturk, M.; Alan, S.; Usluoglu, F.; Akbas, M.; Vurgec, B.A. Identification of the Level of Perceived Social Support and Hope of Cancer Patients and Their Families. World Cancer Res. J. 2017, 4, e886. [Google Scholar]

- Uslu-Sahan, F.; Terzioglu, F.; Koc, G. Hopelessness, Death Anxiety, and Social Support of Hospitalized Patients with Gynecologic Cancer and Their Caregivers. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 42, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, L.J.; Humphris, G.M.; Macfarlane, G. A Meta-Analytic Investigation of the Relationship between the Psychological Distress of Cancer Patients and Their Carers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipiak, G. The Function of Social Support in the Family. UAM 1999, XI, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

| Author/Year | Context (Study Site) | Project (Design) | Aim of Study | Tools | Group of Subjects | Statistical Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Caregivers | ||||||

| Ayik et al. [23] 2022 | Patients hospitalised in the oncology (medical and radiation oncology) clinic in a university hospital in eastern Turkey | A cross-sectional design | To find out the interrelation between the quality of life and social support of cancer patients and caregivers. | Patient and Caregiver Identification Questionnaire, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, Rolls Royce Quality of Life Scale | 318 | 318 | Descriptive statistics, the Kruskal–Wallis, the ANOVA, and the Pearson’s correlation test; the level of error was accepted as a p-value of <0.05. |

| Boeding et al. [24] 2014 | Couples were recruited from two major medical centres in the context of a larger treatment-outcome study. USA | A cross-sectional design | To examine the ways in which a woman’s daily mood, pain, fatigue, and her spouse’s marital satisfaction predict the woman’s report of partner support in the context of breast cancer. | Source-Specific Social Provisions Scale, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, Brief Pain Inventory, Brief Fatigue Inventory, Baseline Measure: Quality of Marriage Index | 158 | 159 | Multilevel modelling (MLM) was used following the guidelines put forth by Raudenbush and Bryk (2002) in order to evaluate the effects of women’s pain, fatigue, and mood and men’s marital satisfaction on the amount of social support provided to women with breast cancer over a span of 30 days. |

| Chen et al. [25] 2021 | First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University and the First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China in Anhui province. | A cross-sectional design | To examine the impact of family resilience on the individual resilience of couples during cancer and explore the potential mediating role of perceived social support and the moderating role of sex in this association in cancer patient-spouse dyads. | Family Resilience Assessment Scale, Perceived Social Support Scale, Resilience Scale | 272 | 272 | Descriptive Statistics, Pearson’s correlations, the mediation of their own and their partners’ perceived social support, and the actor–partner independence mediation model (APIMeM). |

| Dębska et al. [26] 2017 | The Centre of Oncology, M. Skłodowska-Curie Memorial Institute in Cracow and at the St. Luke Provincial Hospital in Tarnów. Poland | A cross-sectional self-inventory study | To determine the level and sources of support available for cancer patients and their close relatives. | Berlin Social Support Scales and a sociodemographic-clinical survey | 193 | 193 | Student t-test and ANOVA (with LSD post-hoc test), Cohen’s d-coefficients. The power and direction of associations within pairs of variables were determined on the basis of Kendall’s tau-b coefficients of linear correlation. |

| Goldzweig et al. [27] 2016 | The Institute of Oncology at Hadassah University Hospital; patients from various geographic regions of Israel were targeted. Israel, Austria | A cross-sectional study | To assess relationships between oldest andold (minimum 86 years) patients’ perceived social support with their own and their spousal caregivers’ hope through the application of the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM). | Social support, the Cancer Perceived Agents of Social Support, Geriatric Depression Scale, the distress thermometer, the Adult Hope Scale | 58 | 58 | Paired t-tests after establishing an interaction between role and gender and validating significant results in multi-analysis of variance [MANOVA] overall variables. Pearson’s zero-order correlation coefficients; the SPSS (version 21.0; IBM Corp. NY, USA) software. |

| Hasson-Ohayon et al. [28] 2014 | Hadassah University Hospital, Jerusalem, Israel. Israel, USA | A cross-sectional study | To compare the relationship between social support, hope, and depression among different age groups of women with advanced breast cancer and their healthy spouses. | Cancer perceived agents of social support, the brief symptom inventory (BSI), the Adult Hope Scale | 150 | 150 | Descriptive statistics, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), and structural equation modelling (SEM). |

| Jeong et al. [29] 2017 | Gastric cancer patients and their family caregivers who visited a university medical centre. South Korea | A cross-sectional study | To investigate the moderating role of social support on the psychological well-being of both cancer patients and family caregivers. | Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | 52 | 36 | Hierarchical multiple regression analyses. |

| Law et al. [30] 2018 | The Radiation Oncology Department at The Canberra Hospital. Canberra, Australia | qualitative study | To gain an in-depth understanding of CRC patients’ and caregivers’ experience of social support within the cancer treatment setting. | Individual interviews | 22 | 22 | The framework approach, qualitative content analysis, consisted of five interconnected stages linked to forming a methodical and rigorous audit trail. |

| Pasek et al. [31] 2022 | Patients were in the chemotherapy and radiotherapy wards of oncology hospitals in Poland, and their caregivers Poland | Across-sectional study | To investigate the factors influencing the multidimensional aspect of social support in a cancer patient-informal caregiver dyad. | Standardised: BSSS, POS, SSCS, TIPI, ET, SPT, the authors’ own tool for sociodemographic assessment. | 170 | 170 | Descriptive statistics, non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test, multiple regression analysis using the stepwise progressive method, analysis of the distribution of residuals. |

| Pasek et al. [10] 2017 | Patients in the chemotherapy and radiotherapy wards of oncology hospitals in Poland and their caregivers. Poland | A cross-sectional study | To analyse interrelationships between perceived support and the SOC in caregivers, and perceived support, the SOC, and acceptance of illness in cancer patients. | Standardised: BSSS, AIS, SOC-29, the authors’ own tool for sociodemographic assessment. | 80 | 80 | Descriptive statistics, analyses using Student’s t-test, Cohen’s d coefficient, analysis of r-Pearson’s correlation coefficients, serial bootstrapping mediation analysis—PROCESS macro for SPSS. |

| Sterba et al. [32] 2017 | The study was conducted at a head and neck cancer (HNC) clinic in a regional cancer centre. The interested participants nominated primary caregivers, the person they reported relying on most for cancer-related support. USA | A cross-sectional study | To examine the physical and emotional well-being and social support in newly diagnosed HNC patients and caregivers and identify sociodemographic, clinical, and behavioural risk factors associated with compromised well-being in patients and caregivers. | The Short Form Health Survey (SF-12), open-ended questions so participants could respond in their own words, the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory tool for sociodemographic assessment | 72 | 72 | Descriptive statistics, ANOVAs and Fisher’s exact tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively (p < 0.05). |

| Surucu et al. [33] 2017 | University Hospital’s Gynaecologic Oncology service in Southern Turkey. | A cross-sectional study | To analyse the level of perceived social support and hope of cancer patients and their families. | Patient Social Support Form and Family Social Support Form, the Beck Hopelessness Scale | 69 | 69 | Arithmetic average, standard deviation, Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal–Wallis test, Spearman–Brown correlation analysis. |

| Uslu-Sahan [34] 2018 | Patients with gynaecologic cancer and their caregivers at one university hospital in Ankara, Turkey. | A cross-sectional study | To determine whether hospitalised patients with gynaecologic cancer and their caregivers differ in feelings of hopelessness and death anxiety and how those conditions may be related to their social support. | Patient Information Form, Caregiver Information Form, the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale, the Beck Hopelessness Scale, the Thorson-Powell’s Death Anxiety Scale (DAS) | 200 | 200 | Student’s t-test, Pearson’s correlation test, and linear regression analyses. The data were analysed using the SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). |

| Author/Year of Publication | Type of Social Support Studied | Key Results |

|---|---|---|

| Ayik et al. [23] | social support | The relationship between the MSPSS and Rolls Royce Quality of Life Scale of the patients was investigated; a positively important connection was determined between perceived total social support and general quality of life subscales of general well-being, medical interaction, sexual function, physical symptoms and activity, social relations, business performance scores and the total mean scores. There was a positive and important relationship between the MSPSS subscales and the total mean scores of patients and caregivers. |

| Boeding et al. [24] | partner support, social support, perceived support | Results show that on days in which women reported higher levels of negative or positive mood, as well as on days they reported more pain and fatigue, they reported receiving more support. Women who, on average, reported higher levels of positive mood tended to report receiving more support than those who, on average, reported lower positive mood. However, average levels of negative mood were not associated with support. Higher average levels of fatigue but not pain was associated with higher support. Finally, women whose husbands reported higher levels of marital satisfaction reported receiving more partner support, but husbands’ marital satisfaction did not moderate the effect of women’s mood on support. |

| Chen et al. [25] | social support, perceived social support, practical social support, friends support, family support | The results indicated that the patients’ and their spouses’ level of family resilience was positively associated with their own individual resilience directly and indirectly by increasing their own perceived social support. The family resilience of the spouses was associated with an increase in the patients’ individual resilience only indirectly by increasing the patients’ perceived social support. The spouse-actor effects between family resilience and individual resilience differed significantly by sex. |

| Dębska et al. [26] | support: instrumental, emotional, informational support, perceived (emotional instrumental), received (emotional; instrumental; informational; satisfaction with support) | Cancer patients had more perceived and received social support than their caregivers. Patients identified more sources of available support than their caregivers. When the level of support was stratified according to the caregiver’s relationship with the patient, caregivers-partners, and caregivers-children presented higher levels of perceived support than caregivers-siblings and caregivers-parents. Caregivers received less support than patients from medical personnel. |

| Goldzweig et al. [27] | social support | Patients presented high distress levels. Among patients and spouses, perceived social support was positively correlated to their own level of hope and negatively correlated to the other’s level of hope. |

| Hasson-Ohayon et al. [28] | sample, emotional, cognitive and instrumental support | Older patients and spouses reported lower levels of depression than younger ones. SEM showed that social support related directly to depression among younger women and older spouses, while hope was directly related to depression among older women and younger spouses, and acted as a mediator between social support and depression. |

| Jeong et al. [29] | perceived support | Patients’ income and social support were related to depression and anxiety, but the interaction of income and social support was only observed for anxiety. For caregivers, no interaction effects were found. Social support decreased the negative effects of low-income status on the patients. No predictors related to patients’ health or living status explained caregivers’ depression and anxiety in Model I. When social support was entered in Model II, patients’ age had a marginally significant effect on patients’ depression; patients’ income had significant predictability of patients’ anxiety. Additionally, patients’ social support predicted patients’ anxiety, whereas caregivers’ social support explained both the depression and anxiety of caregivers. There was no dyadic effect: patients’ social support neither predicted caregivers’ outcomes, nor did caregivers’ social support predict patients’ outcomes. Patients’ depression was explained by patients’ income, and patients’ anxiety was explained by income and social support, including their interaction. For caregivers’ outcomes, no predictors related to patients’ status nor did caregivers’ social support had significant predicting power. |

| Law et al. [30] | social support | Three major themes emerged from the data: (a) treating the team as a source of support, highlighting the importance of connection with the treating team; (b) changes in existing social supports, encompassing issues regarding distance in interpersonal relationships as a consequence of cancer; and (c) differing dimensions of support, exploring the significance of shared experience, practical, financial, and emotional support. |

| Pasek et al. [31] | perceived support: available, emotional, instrumental, the need for support, seeking support currently received, protective buffering support, emotional support, instrumental support, information support, satisfaction with support | On the support scales, statistically significant differences between the examined patients and their caregivers occurred for the support currently received (p ≤ 0.01), emotional support (p ≤ 0.05), and the general level of received protective buffering support (p ≤ 0.001). The study showed statistically significant differences in the scales of currently received support and emotional support. In both cases, the values of support indicated by patients were higher than those indicated by caregivers. On the scale of protective buffering support, the sense of support was significantly higher in caregivers than in patients. No statistically significant differences were observed in the groups of patients and their caregivers on the scales of perceived emotional support, perceived information support, the need for support, sense of support, instrumental support and information support. There was a statistically significant correlation between information support in the group of caregivers and the need for support (0.23) and the sense of support (0.16) in the group of patients. A positive correlation was obtained, indicating that the increase in information support for carers increased the need for support and the sense of support in patients. |

| Pasek et al. [10] | perceived support | Perceived social support scores were high in both groups; still, the values of this parameter in cancer patients turned to be higher than in their caregivers. In both patients (t = −3.82; p < 0.001; d = 0.40) and their caregivers (t = −2.25; p = 0.027; d = 0.21), the level of perceived instrumental support was higher than the level of perceived emotional support. This points to the important role of the interaction between the patient and their close relatives as a determinant of illness acceptance. |

| Sterba et al. [32] | received and provided support | The most frequently approved type of support identified by both patients and caregivers was emotional support, with frequent emphasis on specific types of emotional support in the form of spiritual help and help for patients with aesthetic problems and addictions. Caregivers were also more likely than patients to commonly emphasise the provision of critical instrumental support, including help with finances, transportation to appointments, cooking and other household chores. |

| Surucu et al. [33] | perceived social support, emotional and material support, information support | No significant correlation was found between the perceived social support of cancer patients from their relatives and the social support the relatives think they provided for the patients. Patients’ perceived social support from their relatives is higher than what the relatives think they provide for the patients. The patients and relatives had very high levels of hope; no significant correlation was found. |

| Uslu-Sahan [34] | social support, emotional support, perceived social support | Patients had higher hopelessness and death anxiety compared with caregivers. Patients’ perceived social support explained 35% of the total variance in hopelessness and 28% of the variance in death anxiety; caregivers’ perceived social support explained 40% of the total variance in hopelessness and 12% of the variance in death anxiety. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pasek, M.; Goździalska, A.; Jochymek, M.; Caruso, R. Social Support in a Cancer Patient-Informal Caregiver Dyad: A Scoping Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 1754. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061754

Pasek M, Goździalska A, Jochymek M, Caruso R. Social Support in a Cancer Patient-Informal Caregiver Dyad: A Scoping Review. Cancers. 2023; 15(6):1754. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061754

Chicago/Turabian StylePasek, Małgorzata, Anna Goździalska, Małgorzata Jochymek, and Rosario Caruso. 2023. "Social Support in a Cancer Patient-Informal Caregiver Dyad: A Scoping Review" Cancers 15, no. 6: 1754. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061754

APA StylePasek, M., Goździalska, A., Jochymek, M., & Caruso, R. (2023). Social Support in a Cancer Patient-Informal Caregiver Dyad: A Scoping Review. Cancers, 15(6), 1754. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061754