Determining Optimal Cut-Off Value of Pancreatic-Cancer-Induced Total Cholesterol and Obesity-Related Factors for Developing Exercise Intervention: Big Data Analysis of National Health Insurance Sharing Service Data

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Subject Population

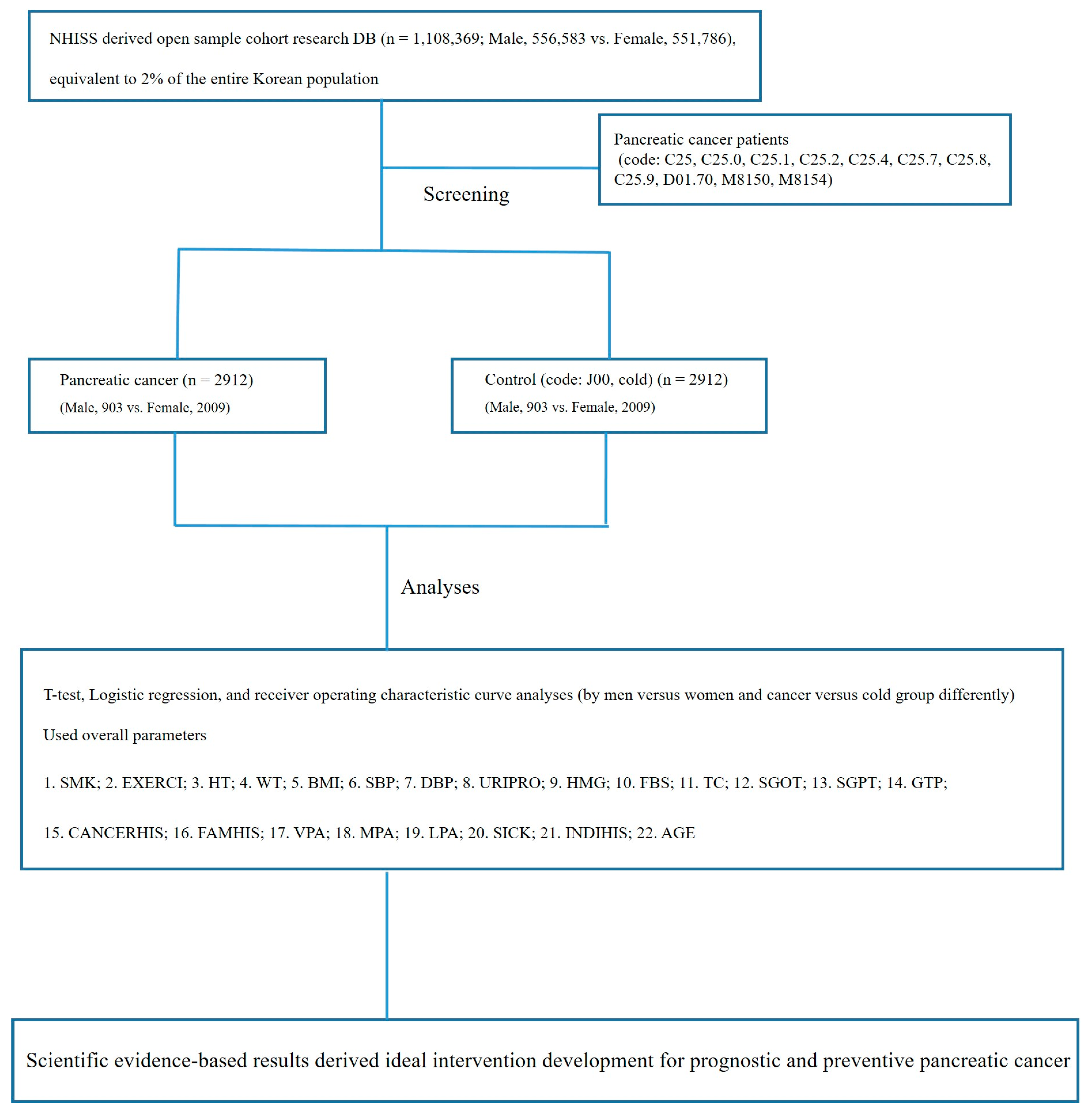

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Categorization of Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Comparison between Cancer and Non-Cancer Groups in Both Sexes

3.3. Sex Differences in Pancreatic Cancer Incidence

3.4. Sex Differences in Pancreatic Cancer Incidence by Exercise

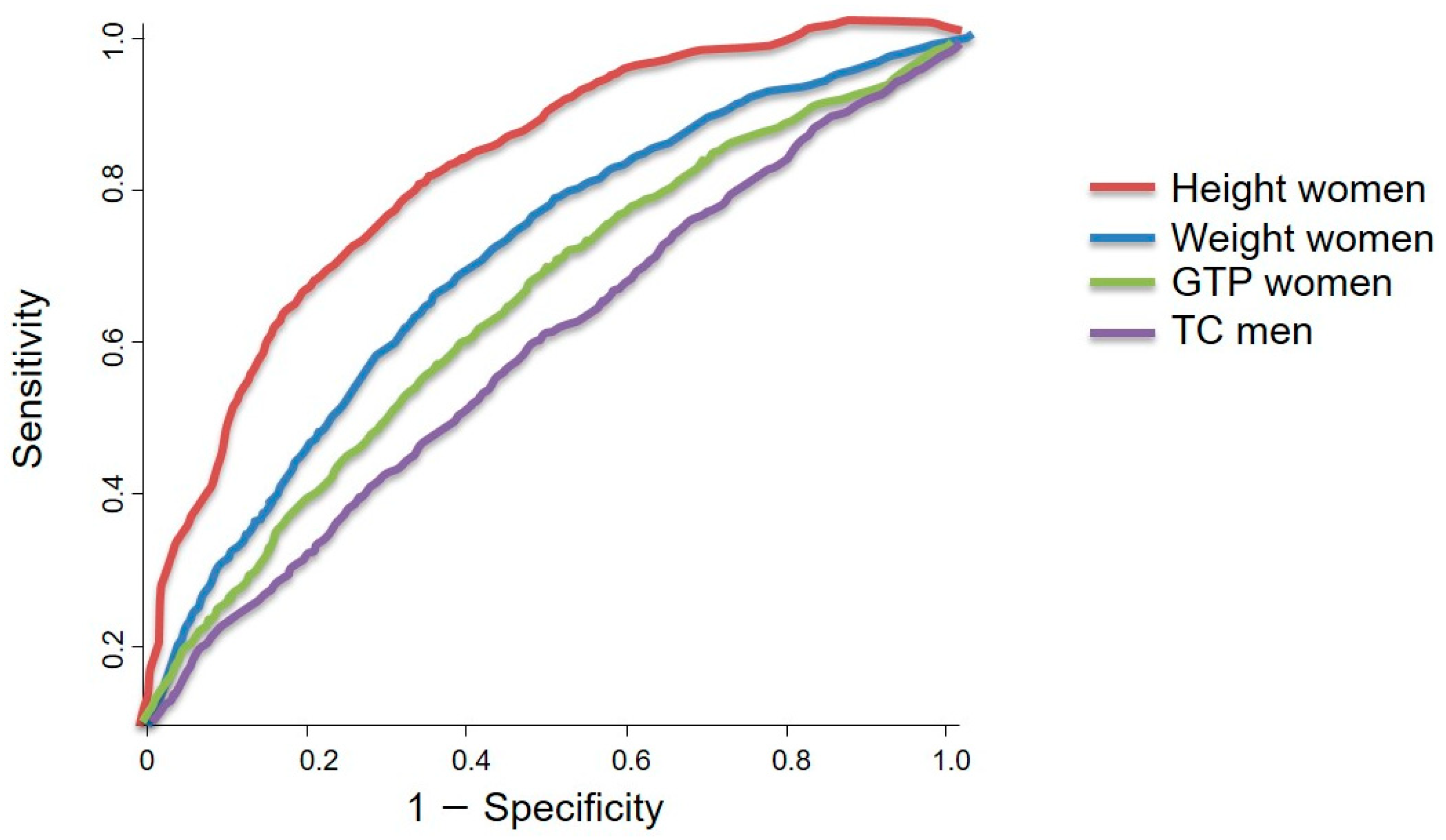

3.5. Sex-Specific Obesity-Related Output from ROC Curve Analysis and the Summary of the Results

- Of the 1,108,369 patients registered in the NHISS DB, 2912 patients with pancreatic cancer (903 men and 2009 women) were included in this study.

- BMI, SBP, DBP, and fasting blood glucose and total cholesterol levels were significantly lower in women with pancreatic cancer than those in the non-cancer group (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, the height, weight, hemoglobin, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase and alanine aminotransaminase (SGPT), and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GTP) concentrations were lower in women with pancreatic cancer (p < 0.001). In men, the height, weight, SBP, DBP, hemoglobin, fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase and aspartate aminotransferase (SGOT), and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase concentrations were significantly different between the pancreatic cancer and non-cancer groups (p < 0.05).

- In the logistic regression analysis, a smoking history of <29 years had a higher OR (1.975–5.332) than other parameters in men, and women also had a higher pancreatic cancer incidence if they had a smoking history (OR, 8.936–18.330).

- Of all the types of exercise assessed, daily exercise was beneficial to lowering the risk of pancreatic cancer in men.

- The ROC curve analysis revealed that the total cholesterol concentration was the only significant factor associated with pancreatic cancer in men (p < 0.05). The ideal cut-off value for total cholesterol concentration was 188.50 mg/dL, which showed a sensitivity and specificity of 53.5% and 54.6%, respectively. However, height, weight, and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase concentration were the factors associated with pancreatic cancer in women, with ideal cut-off values of 165.50 cm, 58.50 kg, and 20.50 U/L, respectively. These cut-off values showed a sensitivity range of 57.3–76.3% and a specificity range of 57.4–75.8%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Related Results

4.2. Association between Obesity and Pancreatic Cancer

4.3. Effects of Physical Activity on Pancreatic Cancer via Obesity Modulation

5. Conclusions

- BMI, SBP, DBP, fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase and aspartate aminotransferase (SGOT) concentrations, and age were lower in women with pancreatic cancer than in women in the corresponding non-cancer group (p < 0.05). In men, the height, weight, SBP, DBP, hemoglobin, fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase and aspartate aminotransferase (SGOT), and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase concentrations were significantly different between the pancreatic cancer and non-cancer groups (p < 0.05).

- A higher number of years of smoking and obesity-related parameters, such as total cholesterol concentration, are applicable only in men, and a higher number of years of smoking, height, weight, hemoglobin, serum glutamine pyruvic transaminase and alanine aminotransaminase (SGPT), and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase concentrations in women were associated with a higher incidence risk of pancreatic cancer (p < 0.05).

- High- or moderate-intensity daily exercise was associated with a lower risk of pancreatic cancer (p < 0.05).

- The ROC curve analysis revealed that total cholesterol concentration (p < 0.05) was the only significant factor associated with pancreatic cancer in men. The optimal cholesterol concentration cut-off value of 188.50 mg/dL showed a sensitivity and specificity of 53.5% and 54.6%, respectively. For women, the height, weight, and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase concentration had optimal cut-off values of 165.0 cm, 58.50 kg, and 20.50 U/L, respectively, for pancreatic cancer risk.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Manen, L.; Groen, J.V.; Putter, H.; Vahrmeijer, A.L.; Swijnenburg, R.-J.; Bonsing, B.A.; Mieog, J.S.D. Elevated CEA and CA19-9 serum levels independently predict advanced pancreatic cancer at diagnosis. Biomarkers 2020, 25, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gapstur, S.M.; Gann, P.H.; Lowe, W.; Liu, K.; Colangelo, L.; Dyer, A. Abnormal glucose metabolism and pancreatic cancer mortality. JAMA 2000, 283, 2552–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.-X.; Zhao, C.-F.; Chen, W.-B.; Liu, Q.-C.; Li, Q.-W.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Gao, F. Pancreatic cancer: A review of epidemiology, trend, and risk factors. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feitelson, D.G. Data on the distribution of cancer incidence and death across age and sex groups visualized using multilevel spie charts. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 72, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, E.-K.; Park, H.J.; Oh, C.-M.; Jung, K.-W.; Shin, H.Y.; Park, B.K.; Won, Y.-J. Cancer incidence and survival among adolescents and young adults in Korea. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, L.; Bennett, K.; Connolly, D. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 26, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Cioffi, G.; Wang, J.; Waite, K.A.; Ostrom, Q.T.; Kruchko, C.; Lathia, J.D.; Rubin, J.B.; Berens, M.E.; Connor, J.; et al. Sex differences in cancer incidence and survival: A pan-cancer analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.B.; McGlynn, K.A.; Devesa, S.S.; Freedman, N.D.; Anderson, W.F. Sex disparities in cancer mortality and survival. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2011, 20, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, D.S.; Giovannucci, E.; Willett, W.C.; Colditz, G.A.; Stampfer, M.J.; Fuchs, C.S. Physical activity, obesity, height, and the risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA 2001, 286, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casari, I.; Falasca, M. Diet and pancreatic cancer prevention. Cancers 2015, 7, 2309–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’rorke, M.A.; Cantwell, M.M.; Cardwell, C.R.; Mulholland, H.G.; Murray, L.J. Can physical activity modulate pancreatic cancer risk? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 2957–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, D.W.; Lahart, I.; Carmichael, A.R.; Koutedakis, Y.; Metsios, G.S. Cancer cachexia prevention via physical exercise: Molecular mechanisms. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2013, 4, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jee, H.; Kim, J.H. Gender difference in colorectal cancer indicators for exercise interventions: The national health insurance sharing service-derived big data analysis. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2019, 15, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jee, H.; Lee, H.-D.; Lee, S.Y. Evidence-based cutoff threshold values from receiver operating characteristic curve analysis for knee osteoarthritis in the 50-year-old Korean population: Analysis of big data from the national health insurance sharing service. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2013671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C.; Winters-Stone, K.; Lee, A.; Schmitz, K.H. Cancer, physical activity, and exercise. Compr. Physiol. 2012, 2, 2775–2809. [Google Scholar]

- Wahutu, M.; Vesely, S.K.; Campbell, J.; Pate, A.; Salvatore, A.L.; Janitz, A.E. Pancreatic cancer: A survival analysis study in Oklahoma. J. Okla. State Med. Assoc. 2016, 109, 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, A.; McIntosh, W.B. Elevation of serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase in end-stage chronic renal failure. Scott. Med. J. 1975, 20, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cowley, L.A.; Liu, X.S. Sex differences in cancer immunotherapy efficacy, biomarkers, and therapeutic strategy. Molecules 2019, 24, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortona, E.; Pierdominici, M.; Rider, V. Sex hormones and gender differences in immune responses. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Köhler, S.; Klotz, R.; Giese, N.; Hackert, T.; Springfeld, C.; Jäger, D.; Halama, N. Sex Differences in the Systemic and Local Immune Response of Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Cancers 2023, 15, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.Y.; Jung, J.H.; Park, M.J.; Kim, S.H. Risk assessment of metabolic syndrome in adolescents using the triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and the total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 24, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tak, Y.-J.; Yoo, S.-M.; Cho, B.-L.; Song, Y.-M.; Yoo, T.-W. Factors related to serum total cholesterol. Korean J. Fam. Med. 1992, 13, 935–942. [Google Scholar]

- Khadka, R.; Tian, W.J.; Xin, H.; Koirala, R. Risk factor, early diagnosis and overall survival on outcome of association between pancreatic cancer and diabetes mellitus: Changes and advances, a review. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 52, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud, D.S. Obesity and pancreatic cancer. Recent. Results Cancer Res. 2016, 208, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Dseagu, V.L.; Devesa, S.S.; Goggins, M.; Stolzenberg-Solomon, R. Pancreatic cancer incidence trends: Evidence from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) population-based data. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.; Park, H.; Lee, K.; Park, J.; Eisenhut, M.; van der Vliet, H.J.; Kim, G.; Shin, J. Body mass index and 20-specific cancers: Re-analyses of dose-response meta-analyses of observational studies. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 29, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, A.C.; Astsaturov, I.; Golemis, E.A. Intrapancreatic fat, pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancer. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, A. Obesity-associated breast cancer: Analysis of risk factors. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 960, 571–606. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, T.; Lyon, C.J.; Bergin, S.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Hsueh, W.A. Obesity, inflammation, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol.-Mech. 2016, 11, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, H.; Chang, J.-E.; Yang, E.J. Positive prehabilitative effect of intense treadmill exercise for ameliorating cancer cachexia symptoms in a mouse model. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 7, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, H.; Park, E.; Hur, K.; Kang, M.; Kim, Y. High-Intensity Aerobic Exercise Suppresses Cancer Growth by Regulating Skeletal Muscle-Derived Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressors. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 818470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldhauer, I.; Steinle, A. NK cells and cancer immunosurveillance. Oncogene 2008, 27, 5932–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raskov, H.; Orhan, A.; Christensen, J.P.; Gogenur, I. Cytotoxic CD8+T cells in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koivula, T.; Lempiäinen, S.; Rinne, P.; Hollmén, M.; Sundberg, C.J.; Rundqvist, H.; Minn, H.; Heinonen, I. Acute exercise mobilizes CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and NK cells in lymphoma patients. Front. Physiol. 2023, 13, 1078512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, A.M.; Agha, N.H.; Baker, F.L.; Niemiro, G.M.; Mylabathula, P.L.; Brewster, A.M.; Bevers, T.B.; Fuentes-Mattei, E.; Basen-Engquist, K.; Gilchrist, S.C.; et al. The impact of high-intensity interval exercise training on NK-cell function and circulating myokines for breast cancer prevention among women at high risk for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 187, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zheng, W.; Xiang, Y.-B.; Gao, Y.-T.; Li, H.-L.; Cai, H.; Shu, X.-O. Physical activity and pancreatic cancer risk among urban Chinese: Results from two prospective cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2018, 27, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Gaduputi, V. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: Global trends, etiology and risk factors. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Whole registered population | 1,108,369 (Men, 556,583; Women, 551,786) |

| Age (years) | 0~85 |

| Total follow-up years | 2002–2015 (14 years) |

| Study contents | Disabilities, diseases, death, current state of medical treatment, etc. |

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Non-Cancer | Cancer | Non-Cancer | |

| HT | 163.60 ± 8.78 *** | 165.60 ± 6.34 | 163.30 ± 9.06 *** | 152.20 ± 6.42 |

| WT | 63.90 ± 11.79 * | 65.14 ± 10.14 | 63.60 ± 12.08 *** | 55.74 ± 9.06 |

| BMI | 23.78 ± 3.41 | 23.68 ± 2.96 | 23.75 ± 3.43 * | 24.04 ± 3.43 |

| SBP | 122.60 ± 15.57 *** | 127.50 ± 15.40 | 122.10 ± 14.42 *** | 127.50 ± 16.12 |

| DBP | 76.40 ± 9.95 * | 77.39 ± 10.40 | 76.12 ± 10.22 * | 76.82 ± 9.68 |

| HMG | 14.07 ± 1.55 ** | 14.30 ± 15.60 | 13.99 ± 1.62 *** | 12.76 ± 1.34 |

| FBS | 98.29 ± 23.56 *** | 107.00 ± 29.21 | 97.68 ± 30.12 *** | 103.20 ± 29.35 |

| TC | 196.40 ± 39.40 *** | 185.20 ± 38.58 | 194.60 ± 6.52 *** | 201.00 ± 41.04 |

| SGOT | 25.26 ± 13.64 *** | 29.01 ± 19.75 | 25.39 ± 15.69 | 25.43 ± 12.65 |

| SGPT | 25.22 ± 24.36 | 26.78 ± 23.65 | 25.04 ± 21.07 *** | 21.30 ± 13.98 |

| GTP | 35.10 ± 39.80 *** | 47.65 ± 76.70 | 37.38 ± 56.61 *** | 24.86 ± 27.46 |

| AGE | 56.69 ± 11.71 | 56.68 ± 11.70 | 57.95 ± 11.34 | 57.96 ± 11.34 |

| Parameters | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.R. | 95% CI | O.R. | 95% CI | |

| SMK (1) | 5.332 | 1.821~15.612 | 15.954 | 6.928~36.742 |

| SMK (2) | 4.120 | 2.434~6.974 | 18.330 | 9.912~33.894 |

| SMK (3) | 1.975 | 1.304~2.993 | 11.580 | 6.641~20.191 |

| SMK (4) | 0.331 | 0.234~0.470 | 8.936 | 5.270~15.152 |

| HT | 0.967 | 0.955~0.979 | 1.197 | 1.183~1.212 |

| WT | 0.990 | 0.981~0.999 | 1.075 | 1.067~1.083 |

| BMI | 1.010 | 0.981~1.041 | 0.976 | 0.957~0.994 |

| SBP | 0.980 | 0.974~0.986 | 0.978 | 0.974~0.983 |

| DBP | 0.990 | 0.981~1.000 | 0.993 | 0.987~1.000 |

| URIPRO (1) | 1.122 | 0.595~2.117 | 0.769 | 0.494~1.198 |

| URIPRO (2) | 0.705 | 0.366~1.356 | 0.884 | 0.545~1.435 |

| URIPRO (3) | 0.948 | 0.342~2.627 | 0.176 | 0.067~0.463 |

| URIPRO (4) | 0.415 | 0.076~2.271 | 0.270 | 0.028~2.594 |

| HMG | 0.908 | 0.853~0.967 | 1.773 | 1.682~1.869 |

| FBS | 0.986 | 0.982~0.990 | 0.992 | 0.990~0.995 |

| TC | 1.007 | 1.005~1.010 | 0.996 | 0.994~0.997 |

| SGOT | 0.983 | 0.976~0.991 | 1.000 | 0.995~1.004 |

| SGPT | 0.997 | 0.993~1.001 | 1.014 | 1.010~1.019 |

| GTP | 0.996 | 0.993~0.998 | 1.013 | 1.010~1.016 |

| CANCERHIS | 0.374 | 0.257~0.543 | 0.345 | 0.273~0.434 |

| FAMHIS | 1.066 | 0.794~1.431 | 0.957 | 0.772~1.187 |

| Parameters | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.R. | 95% CI | O.R. | 95% CI | |

| EXERCI (1) | 1.294 | 0.661~2.534 | 1.939 | 1.231~3.055 |

| EXERCI (2) | 1.264 | 0.482~3.313 | 1.826 | 0.863~3.862 |

| EXERCI (3) | 2.123 | 0.253~17.816 | 4.014 | 0.512~31.439 |

| EXERCI (4) | 0.227 | 0.089~0.582 | 1.014 | 0.459~2.243 |

| VPA (1) | 2.002 | 1.460~2.745 | 2.795 | 2.150~3.634 |

| VPA (2) | 1.151 | 0.783~1.692 | 2.969 | 2.197~4.011 |

| VPA (3) | 1.282 | 0.825~1.992 | 2.325 | 1.704~3.173 |

| VPA (4) | 0.865 | 0.455~1.644 | 1.772 | 1.107~2.837 |

| VPA (5) | 1.638 | 0.908~2.958 | 2.407 | 1.487~3.896 |

| VPA (6) | 0.540 | 0.203~1.436 | 1.760 | 1.000~3.098 |

| VPA (7) | 0.453 | 0.230~0.896 | 1.173 | 0.704~1.957 |

| MPA (1) | 1.568 | 1.121~2.194 | 2.728 | 2.112~3.522 |

| MPA (2) | 1.246 | 0.871~1.784 | 2.520 | 1.939~3.275 |

| MPA (3) | 0.915 | 0.603~1.387 | 1.762 | 1.332~2.332 |

| MPA (4) | 0.937 | 0.552~1.589 | 1.628 | 1.096~2.417 |

| MPA (5) | 1.071 | 0.632~1.814 | 1.705 | 1.118~2.599 |

| MPA (6) | 0.494 | 0.245~0.995 | 1.465 | 0.876~2.452 |

| MPA (7) | 0.535 | 0.314~0.912 | 0.804 | 0.521~1.240 |

| LPA (1) | 1.827 | 1.179~2.830 | 2.179 | 1.651~2.876 |

| LPA (2) | 1.421 | 0.980~2.060 | 2.179 | 1.688~2.812 |

| LPA (3) | 1.375 | 0.963~1.963 | 1.469 | 1.152~1.873 |

| LPA (4) | 1.486 | 0.927~2.385 | 1.598 | 1.184~2.157 |

| LPA (5) | 1.001 | 0.682~1.470 | 1.704 | 1.302~2.231 |

| LPA (6) | 1.011 | 0.628~1.626 | 1.362 | 0.994~1.866 |

| LPA (7) | 0.767 | 0.545~1.081 | 1.130 | 0.886~1.441 |

| Male | Female | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | Cut-Off Values | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC | Cut-Off Values | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

| HT | 0.429 | 164.50 | 46.3 | 43.8 | 0.837 | 165.50 | 76.3 | 75.8 |

| WT | 0.454 | 63.50 | 47.7 | 43.3 | 0.693 | 58.50 | 63.1 | 64.5 |

| TC | 0.575 | 188.50 | 53.5 | 54.6 | 0.456 | 195.50 | 46.4 | 47.5 |

| GTP | 0.398 | 25.50 | 43.0 | 41.9 | 0.602 | 20.50 | 57.3 | 57.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jee, H.; Won, K.S. Determining Optimal Cut-Off Value of Pancreatic-Cancer-Induced Total Cholesterol and Obesity-Related Factors for Developing Exercise Intervention: Big Data Analysis of National Health Insurance Sharing Service Data. Cancers 2023, 15, 5444. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15225444

Jee H, Won KS. Determining Optimal Cut-Off Value of Pancreatic-Cancer-Induced Total Cholesterol and Obesity-Related Factors for Developing Exercise Intervention: Big Data Analysis of National Health Insurance Sharing Service Data. Cancers. 2023; 15(22):5444. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15225444

Chicago/Turabian StyleJee, Hyunseok, and Kim Sang Won. 2023. "Determining Optimal Cut-Off Value of Pancreatic-Cancer-Induced Total Cholesterol and Obesity-Related Factors for Developing Exercise Intervention: Big Data Analysis of National Health Insurance Sharing Service Data" Cancers 15, no. 22: 5444. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15225444

APA StyleJee, H., & Won, K. S. (2023). Determining Optimal Cut-Off Value of Pancreatic-Cancer-Induced Total Cholesterol and Obesity-Related Factors for Developing Exercise Intervention: Big Data Analysis of National Health Insurance Sharing Service Data. Cancers, 15(22), 5444. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15225444