A Review of Nutraceuticals in Cancer Cachexia

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

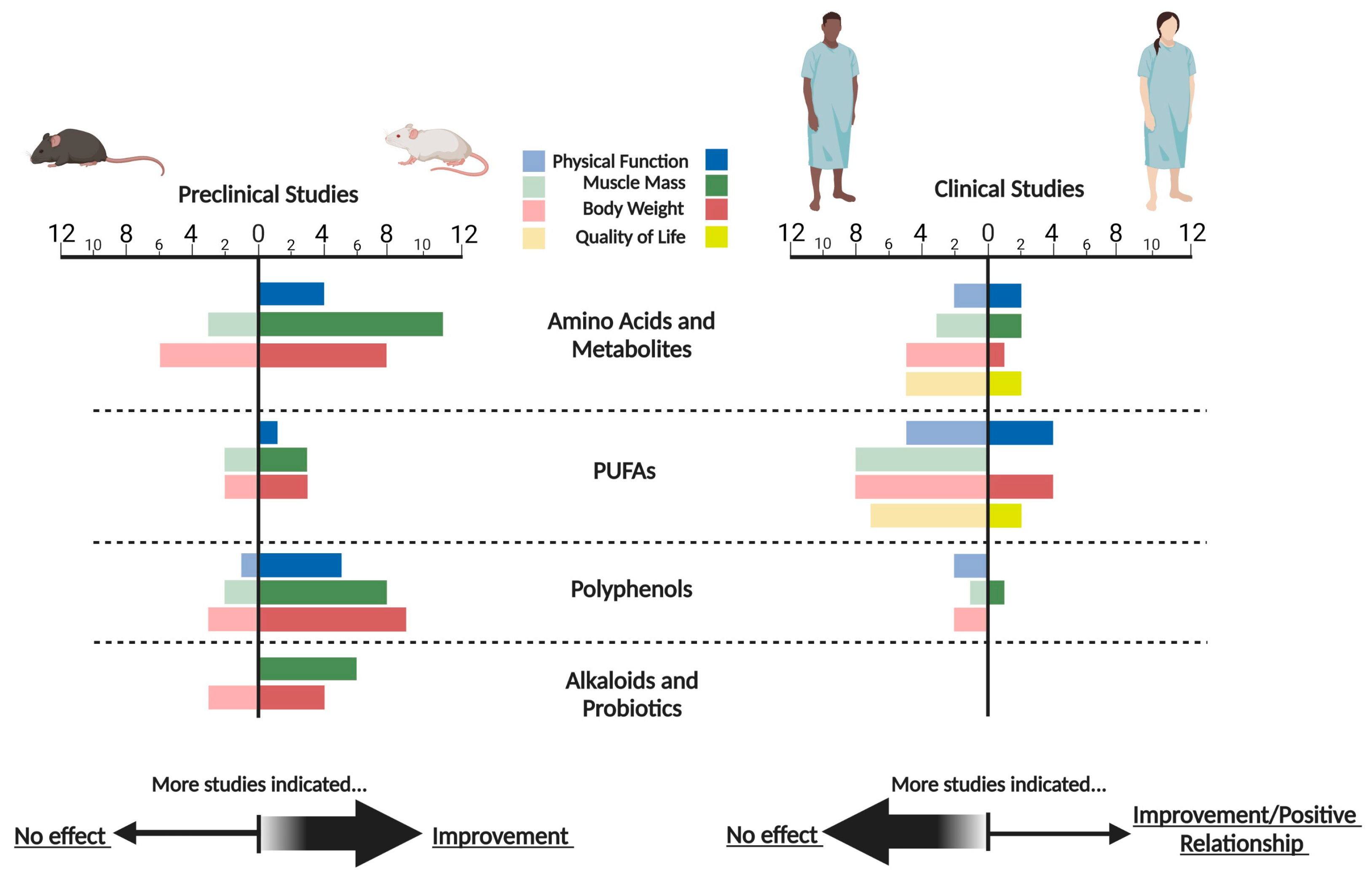

3. Results

3.1. Amino Acids and Metabolites

3.1.1. Essential Amino Acids

3.1.2. HMB, Arginine, Glutamine, and Glycine

3.1.3. Carnitine

3.1.4. Creatine

3.2. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA)

3.2.1. PUFAs Alone

3.2.2. PUFAs with Antioxidants

3.3. Polyphenols

3.3.1. Quercetin

3.3.2. Curcumin

3.3.3. Silibinin

3.3.4. Isoflavones

3.3.5. Resveratrol

3.4. Alkaloids

3.5. Probiotics

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laviano, A.; Koverech, A.; Mari, A. Cachexia: Clinical features when inflammation drives malnutrition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondello, P.; Mian, M.; Aloisi, C.; Fama, F.; Mondello, S.; Pitini, V. Cancer cachexia syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and new therapeutic options. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 67, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utech, A.E.; Tadros, E.M.; Hayes, T.G.; Garcia, J.M. Predicting survival in cancer patients: The role of cachexia and hormonal, nutritional and inflammatory markers. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2012, 3, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laviano, A.; Meguid, M.M. Nutritional issues in cancer management. Nutrition 1996, 12, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.; Johnston, M.; Hancock, M.; Small, S.; Taylor, R.; Dalton, J.; Steiner, M. Enobosarm, a selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM) increases lean body mass (LBM) in advanced NSCLC patients: Updated results of two pivotal, international phase 3 trials. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, S30. [Google Scholar]

- Currow, D.; Temel, J.S.; Abernethy, A.; Milanowski, J.; Friend, J.; Fearon, K.C. ROMANA 3: A phase 3 safety extension study of anamorelin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with cachexia. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1949–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeddu, C.; Dessi, M.; Panzone, F.; Serpe, R.; Antoni, G.; Cau, M.C.; Montaldo, L.; Mela, Q.; Mura, M.; Astara, G.; et al. Randomized phase III clinical trial of a combined treatment with carnitine + celecoxib +/− megestrol acetate for patients with cancer-related anorexia/cachexia syndrome. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, G.; Maccio, A.; Madeddu, C.; Serpe, R.; Massa, E.; Dessi, M.; Panzone, F.; Contu, P. Randomized phase III clinical trial of five different arms of treatment in 332 patients with cancer cachexia. Oncologist 2010, 15, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Temel, J.S.; Abernethy, A.P.; Currow, D.C.; Friend, J.; Duus, E.M.; Yan, Y.; Fearon, K.C. Anamorelin in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and cachexia (ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2): Results from two randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.J.; Albrecht, E.D.; Garcia, J.M. Update on Management of Cancer-Related Cachexia. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jeong, M.I.; Kim, H.R.; Park, H.; Moon, W.K.; Kim, B. Plant Extracts as Possible Agents for Sequela of Cancer Therapies and Cachexia. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagherniya, M.; Mahdavi, A.; Shokri-Mashhadi, N.; Banach, M.; Von Haehling, S.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. The beneficial therapeutic effects of plant-derived natural products for the treatment of sarcopenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2772–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braha, A.; Albai, A.; Timar, B.; Negru, S.; Sorin, S.; Roman, D.; Popovici, D. Nutritional Interventions to Improve Cachexia Outcomes in Cancer-A Systematic Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochamat; Cuhls, H.; Marinova, M.; Kaasa, S.; Stieber, C.; Conrad, R.; Radbruch, L.; Mucke, M. A systematic review on the role of vitamins, minerals, proteins, and other supplements for the treatment of cachexia in cancer: A European Palliative Care Research Centre cachexia project. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Matuoka e Chiocchetti, G.; Viana, L.R.; Lopes-Aguiar, L.; da Silva Miyaguti, N.A.; Gomes-Marcondes, M.C.C. Nutraceuticals Approach as a Treatment for Cancer Cachexia. In Handbook of Nutraceuticals and Natural Products; Gopi, S., Balakrishnan, P., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aquila, G.; Re Cecconi, A.D.; Brault, J.J.; Corli, O.; Piccirillo, R. Nutraceuticals and Exercise against Muscle Wasting during Cancer Cachexia. Cells 2020, 9, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Worp, W.; Schols, A.; Theys, J.; van Helvoort, A.; Langen, R.C.J. Nutritional Interventions in Cancer Cachexia: Evidence and Perspectives From Experimental Models. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 601329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Marcondes, M.C.; Ventrucci, G.; Toledo, M.T.; Cury, L.; Cooper, J.C. A leucine-supplemented diet improved protein content of skeletal muscle in young tumor-bearing rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2003, 36, 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eley, H.L.; Russell, S.T.; Tisdale, M.J. Effect of branched-chain amino acids on muscle atrophy in cancer cachexia. Biochem. J. 2007, 407, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, S.J.; van Helvoort, A.; Kegler, D.; Argilès, J.M.; Luiking, Y.C.; Laviano, A.; van Bergenhenegouwen, J.; Deutz, N.E.; Haagsman, H.P.; Gorselink, M.; et al. Dose-dependent effects of leucine supplementation on preservation of muscle mass in cancer cachectic mice. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 26, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, B.; Oliveira, A.; Gomes-Marcondes, M.C.C. L-leucine dietary supplementation modulates muscle protein degradation and increases pro-inflammatory cytokines in tumour-bearing rats. Cytokine 2017, 96, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, B.; Oliveira, A.; Viana, L.R.; Lopes-Aguiar, L.; Canevarolo, R.; Colombera, M.C.; Valentim, R.R.; Garcia-Fóssa, F.; de Sousa, L.M.; Castelucci, B.G.; et al. Leucine-Rich Diet Modulates the Metabolomic and Proteomic Profile of Skeletal Muscle during Cancer Cachexia. Cancers 2020, 12, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.R.; Chiocchetti, G.M.E.; Oroy, L.; Vieira, W.F.; Busanello, E.N.B.; Marques, A.C.; Salgado, C.M.; de Oliveira, A.L.R.; Vieira, A.S.; Suarez, P.S.; et al. Leucine-Rich Diet Improved Muscle Function in Cachectic Walker 256 Tumour-Bearing Wistar Rats. Cells 2021, 10, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Mukerji, P.; Tisdale, M.J. Attenuation of proteasome-induced proteolysis in skeletal muscle by {beta}-hydroxy-{beta}-methylbutyrate in cancer-induced muscle loss. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aversa, Z.; Bonetto, A.; Costelli, P.; Minero, V.G.; Penna, F.; Baccino, F.M.; Lucia, S.; Rossi Fanelli, F.; Muscaritoli, M. β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB) attenuates muscle and body weight loss in experimental cancer cachexia. Int. J. Oncol. 2011, 38, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ham, D.J.; Murphy, K.T.; Chee, A.; Lynch, G.S.; Koopman, R. Glycine administration attenuates skeletal muscle wasting in a mouse model of cancer cachexia. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wu, H.J.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Chen, Q.; Liu, B.; Wu, J.P.; Zhu, L. L-carnitine ameliorates cancer cachexia in mice by regulating the expression and activity of carnitine palmityl transferase. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 12, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Busquets, S.; Serpe, R.; Toledo, M.; Betancourt, A.; Marmonti, E.; Orpí, M.; Pin, F.; Capdevila, E.; Madeddu, C.; López-Soriano, F.J.; et al. L-Carnitine: An adequate supplement for a multi-targeted anti-wasting therapy in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquets, S.; Pérez-Peiró, M.; Salazar-Degracia, A.; Argilés, J.M.; Serpe, R.; Rojano-Toimil, A.; López-Soriano, F.J.; Barreiro, E. Differential structural features in soleus and gastrocnemius of carnitine-treated cancer cachectic rats. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, P.S.; Marinello, P.C.; Borges, F.H.; Ribeiro, D.F.; Chimin, P.; Testa, M.T.J.; Guirro, P.B.; Duarte, J.A.; Cecchini, R.; Guarnier, F.A.; et al. Creatine supplementation in Walker-256 tumor-bearing rats prevents skeletal muscle atrophy by attenuating systemic inflammation and protein degradation signaling. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, R.; Lin, K.; Jin, X.; Li, L.; Wazir, J.; Pu, W.; Lian, P.; Lu, R.; Song, S.; et al. Creatine modulates cellular energy metabolism and protects against cancer cachexia-associated muscle wasting. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1086662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, J.F.; Goupille, C.; Pinault, M.; Fandeur, L.; Bougnoux, P.; Servais, S.; Couet, C. n-3 PUFA-enriched diet delays the occurrence of cancer cachexia in rat with peritoneal carcinosis. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byerley, L.O.; Chang, H.M.; Lorenzen, B.; Guidry, J.; Hardman, W.E. Impact of dietary walnuts, a nutraceutical option, on circulating markers of metabolic dysregulation in a rodent cachectic tumor model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 155, 113728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.J.; Li, W.H.; Yang, Y.H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, M.Q.; Li, Y.C.; Li, H.; Wu, H.; Du, L. Eicosapentaenoic Acid-Enriched Phospholipids Alleviate Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Lewis Lung Carcinoma Mouse Model. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, e2300033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Norren, K.; Kegler, D.; Argilés, J.M.; Luiking, Y.; Gorselink, M.; Laviano, A.; Arts, K.; Faber, J.; Jansen, H.; van der Beek, E.M.; et al. Dietary supplementation with a specific combination of high protein, leucine, and fish oil improves muscle function and daily activity in tumour-bearing cachectic mice. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Chan, Y.L.; Li, T.L.; Bauer, B.A.; Hsia, S.; Wang, C.H.; Huang, J.S.; Wang, H.M.; Yeh, K.Y.; Huang, T.H.; et al. Reduction of splenic immunosuppressive cells and enhancement of anti-tumor immunity by synergy of fish oil and selenium yeast. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e52912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velázquez, K.T.; Enos, R.T.; Narsale, A.A.; Puppa, M.J.; Davis, J.M.; Murphy, E.A.; Carson, J.A. Quercetin supplementation attenuates the progression of cancer cachexia in ApcMin/+ mice. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levolger, S.; van den Engel, S.; Ambagtsheer, G.; Ijzermans, J.N.M.; de Bruin, R.W.F. Quercetin supplementation attenuates muscle wasting in cancer-associated cachexia in mice. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2021, 6, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderVeen, B.N.; Cardaci, T.D.; Cunningham, P.; McDonald, S.J.; Bullard, B.M.; Fan, D.; Murphy, E.A.; Velázquez, K.T. Quercetin Improved Muscle Mass and Mitochondrial Content in a Murine Model of Cancer and Chemotherapy-Induced Cachexia. Nutrients 2022, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquets, S.; Carbó, N.; Almendro, V.; Quiles, M.T.; López-Soriano, F.J.; Argilés, J.M. Curcumin, a natural product present in turmeric, decreases tumor growth but does not behave as an anticachectic compound in a rat model. Cancer Lett. 2001, 167, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, R.A.; Hassan, S.; Harvey, K.A.; Rasool, T.; Das, T.; Mukerji, P.; DeMichele, S. Attenuation of proteolysis and muscle wasting by curcumin c3 complex in MAC16 colon tumour-bearing mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Quan-Jun, Y.; Jun, B.; Li-Li, W.; Yong-Long, H.; Bin, L.; Qi, Y.; Yan, L.; Cheng, G.; Gen-Jin, Y. NMR-based metabolomics reveals distinct pathways mediated by curcumin in cachexia mice bearing CT26 tumor. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 11766–11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penedo-Vázquez, A.; Duran, X.; Mateu, J.; López-Postigo, A.; Barreiro, E. Curcumin and Resveratrol Improve Muscle Function and Structure through Attenuation of Proteolytic Markers in Experimental Cancer-Induced Cachexia. Molecules 2021, 26, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, J.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Ye, C.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, Q.; Guo, Y. Curcumin Targeting NF-κB/Ubiquitin-Proteasome-System Axis Ameliorates Muscle Atrophy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cachexia Mice. Mediat. Inflamm. 2022, 2022, 2567150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.K.; Dasgupta, A.; Mehla, K.; Gunda, V.; Vernucci, E.; Souchek, J.; Goode, G.; King, R.; Mishra, A.; Rai, I.; et al. Silibinin-mediated metabolic reprogramming attenuates pancreatic cancer-induced cachexia and tumor growth. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 41146–41161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, M.Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.X.; Sun, X.P.; Yang, Q.J.; Guo, C. Silibinin Alleviates Muscle Atrophy Caused by Oxidative Stress Induced by Cisplatin through ERK/FoxO and JNK/FoxO Pathways. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 5694223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirasaka, K.; Saito, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Miyazaki, R.; Wang, Y.; Haruna, M.; Taniyama, S.; Higashitani, A.; Terao, J.; Nikawa, T.; et al. Dietary Supplementation with Isoflavones Prevents Muscle Wasting in Tumor-Bearing Mice. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2016, 62, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Busquets, S.; Fuster, G.; Ametller, E.; Olivan, M.; Figueras, M.; Costelli, P.; Carbó, N.; Argilés, J.M.; López-Soriano, F.J. Resveratrol does not ameliorate muscle wasting in different types of cancer cachexia models. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 26, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadfar, S.; Couch, M.E.; McKinney, K.A.; Weinstein, L.J.; Yin, X.; Rodríguez, J.E.; Guttridge, D.C.; Willis, M. Oral resveratrol therapy inhibits cancer-induced skeletal muscle and cardiac atrophy in vivo. Nutr. Cancer 2011, 63, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iizuka, N.; Hazama, S.; Yoshimura, K.; Yoshino, S.; Tangoku, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Okita, K.; Oka, M. Anticachectic effects of the natural herb Coptidis rhizoma and berberine on mice bearing colon 26/clone 20 adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 99, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, J. Sophocarpine and matrine inhibit the production of TNF-alpha and IL-6 in murine macrophages and prevent cachexia-related symptoms induced by colon26 adenocarcinoma in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2008, 8, 1767–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivan, M.; Springer, J.; Busquets, S.; Tschirner, A.; Figueras, M.; Toledo, M.; Fontes-Oliveira, C.; Genovese, M.I.; Ventura da Silva, P.; Sette, A.; et al. Theophylline is able to partially revert cachexia in tumour-bearing rats. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Varian, B.J.; Gourishetti, S.; Poutahidis, T.; Lakritz, J.R.; Levkovich, T.; Kwok, C.; Teliousis, K.; Ibrahim, Y.M.; Mirabal, S.; Erdman, S.E. Beneficial bacteria inhibit cachexia. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 11803–11816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- An, J.M.; Kang, E.A.; Han, Y.M.; Oh, J.Y.; Lee, D.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, D.H.; Hahm, K.B. Dietary intake of probiotic kimchi ameliorated IL-6-driven cancer cachexia. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2019, 65, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, P.E.; Barber, A.; D’Olimpio, J.T.; Hourihane, A.; Abumrad, N.N. Reversal of cancer-related wasting using oral supplementation with a combination of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate, arginine, and glutamine. Am. J. Surg. 2002, 183, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, L.; James, J.; Schwartz, A.; Hug, E.; Mahadevan, A.; Samuels, M.; Kachnic, L. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a beta-hydroxyl beta-methyl butyrate, glutamine, and arginine mixture for the treatment of cancer cachexia (RTOG 0122). Support. Care Cancer 2008, 16, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruciani, R.A.; Dvorkin, E.; Homel, P.; Culliney, B.; Malamud, S.; Lapin, J.; Portenoy, R.K.; Esteban-Cruciani, N. L-carnitine supplementation in patients with advanced cancer and carnitine deficiency: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2009, 37, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, M.; Kraft, K.; Gartner, S.; Mayerle, J.; Simon, P.; Weber, E.; Schutte, K.; Stieler, J.; Koula-Jenik, H.; Holzhauer, P.; et al. L-Carnitine-supplementation in advanced pancreatic cancer (CARPAN)—A randomized multicentre trial. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gramignano, G.; Lusso, M.R.; Madeddu, C.; Massa, E.; Serpe, R.; Deiana, L.; Lamonica, G.; Dessi, M.; Spiga, C.; Astara, G.; et al. Efficacy of l-carnitine administration on fatigue, nutritional status, oxidative stress, and related quality of life in 12 advanced cancer patients undergoing anticancer therapy. Nutrition 2006, 22, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Stubler, D.; Baier, P.; Schutz, T.; Ocran, K.; Holm, E.; Lochs, H.; Pirlich, M. Effects of creatine supplementation on nutritional status, muscle function and quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer--a double blind randomised controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 25, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatoi, A.; Steen, P.D.; Atherton, P.J.; Moore, D.F.; Rowland, K.M.; Le-Lindqwister, N.A.; Adonizio, C.S.; Jaslowski, A.J.; Sloan, J.; Loprinzi, C. A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of creatine for the cancer anorexia/weight loss syndrome (N02C4): An Alliance trial. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1957–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigmore, S.J.; Ross, J.A.; Falconer, J.S.; Plester, C.E.; Tisdale, M.J.; Carter, D.C.; Fearon, K.C. The effect of polyunsaturated fatty acids on the progress of cachexia in patients with pancreatic cancer. Nutrition 1996, 12, S27–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigmore, S.J.; Barber, M.D.; Ross, J.A.; Tisdale, M.J.; Fearon, K.C. Effect of oral eicosapentaenoic acid on weight loss in patients with pancreatic cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2000, 36, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, C.P.; Halabi, S.; Clamon, G.H.; Hars, V.; Wagner, B.A.; Hohl, R.J.; Lester, E.; Kirshner, J.J.; Vinciguerra, V.; Paskett, E. Phase I clinical study of fish oil fatty acid capsules for patients with cancer cachexia: Cancer and leukemia group B study 9473. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 3942–3947. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, C.P.; Halabi, S.; Clamon, G.; Kaplan, E.; Hohl, R.J.; Atkins, J.N.; Schwartz, M.A.; Wagner, B.A.; Paskett, E. Phase II study of high-dose fish oil capsules for patients with cancer-related cachexia. Cancer 2004, 101, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, C.; Glimelius, B.; Ronnelid, J.; Nygren, P. Impact of fish oil and melatonin on cachexia in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer: A randomized pilot study. Nutrition 2005, 21, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, K.C.; Barber, M.D.; Moses, A.G.; Ahmedzai, S.H.; Taylor, G.S.; Tisdale, M.J.; Murray, G.D. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of eicosapentaenoic acid diester in patients with cancer cachexia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 3401–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jia, Z.; Dong, L.; Wang, R.; Qiu, G. A randomized pilot study of atractylenolide I on gastric cancer cachexia patients. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2008, 5, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottel, L.; Lycke, M.; Boterberg, T.; Pottel, H.; Goethals, L.; Duprez, F.; Maes, A.; Goemaere, S.; Rottey, S.; Foubert, I.; et al. Echium oil is not protective against weight loss in head and neck cancer patients undergoing curative radio(chemo)therapy: A randomised-controlled trial. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2014, 14, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.R.; Dannerfjord, S.; Nørgaard, M.; Lauritzen, L.; Lange, P.; Jensen, N.A. A randomized study of the effect of fish oil on n-3 fatty acid incorporation and nutritional status in lung cancer patients. Austin J. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 2, 1011. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, L.A.; Pletschen, L.; Arends, J.; Unger, C.; Massing, U. Marine phospholipids--a promising new dietary approach to tumor-associated weight loss. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.; Kullenberg de Gaudry, D.; Taylor, L.A.; Keck, T.; Unger, C.; Hopt, U.T.; Massing, U. Dietary supplementation with n-3-fatty acids in patients with pancreatic cancer and cachexia: Marine phospholipids versus fish oil—A randomized controlled double-blind trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gogos, C.A.; Ginopoulos, P.; Salsa, B.; Apostolidou, E.; Zoumbos, N.C.; Kalfarentzos, F. Dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids plus vitamin E restore immunodeficiency and prolong survival for severely ill patients with generalized malignancy: A randomized control trial. Cancer 1998, 82, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruera, E.; Strasser, F.; Palmer, J.L.; Willey, J.; Calder, K.; Amyotte, G.; Baracos, V. Effect of fish oil on appetite and other symptoms in patients with advanced cancer and anorexia/cachexia: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, K.C.; Von Meyenfeldt, M.F.; Moses, A.G.; Van Geenen, R.; Roy, A.; Gouma, D.J.; Giacosa, A.; Van Gossum, A.; Bauer, J.; Barber, M.D.; et al. Effect of a protein and energy dense N-3 fatty acid enriched oral supplement on loss of weight and lean tissue in cancer cachexia: A randomised double blind trial. Gut 2003, 52, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thambamroong, T.; Seetalarom, K.; Saichaemchan, S.; Pumsutas, Y.; Prasongsook, N. Efficacy of Curcumin on Treating Cancer Anorexia-Cachexia Syndrome in Locally or Advanced Head and Neck Cancer: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomised Phase IIa Trial (CurChexia). J. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 2022, 5425619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiworramukkul, A.; Seetalarom, K.; Saichamchan, S.; Prasongsook, N. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomized Phase IIa Study: Evaluating the Effect of Curcumin for Treatment of Cancer Anorexia-Cachexia Syndrome in Solid Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 2333–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Functional amino acids in nutrition and health. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campos-Ferraz, P.L.; Bozza, T.; Nicastro, H.; Lancha, A.H., Jr. Distinct effects of leucine or a mixture of the branched-chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) supplementation on resistance to fatigue, and muscle and liver-glycogen degradation, in trained rats. Nutrition 2013, 29, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Campos-Ferraz, P.L.; Andrade, I.; das Neves, W.; Hangai, I.; Alves, C.R.; Lancha, A.H., Jr. An overview of amines as nutritional supplements to counteract cancer cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2014, 5, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Martínez, A.D.; León Idougourram, S.; Muñoz Jiménez, C.; Rodríguez-Alonso, R.; Alonso Echague, R.; Chica Palomino, S.; Sanz Sanz, A.; Manzano García, G.; Gálvez Moreno, M.; Calañas Continente, A.; et al. Standard Hypercaloric, Hyperproteic vs. Leucine-Enriched Oral Supplements in Patients with Cancer-Induced Sarcopenia, a Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopman, R.; Caldow, M.K.; Ham, D.J.; Lynch, G.S. Glycine metabolism in skeletal muscle: Implications for metabolic homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2017, 20, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bear, D.E.; Langan, A.; Dimidi, E.; Wandrag, L.; Harridge, S.D.R.; Hart, N.; Connolly, B.; Whelan, K. beta-Hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate and its impact on skeletal muscle mass and physical function in clinical practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prado, C.M.; Orsso, C.E.; Pereira, S.L.; Atherton, P.J.; Deutz, N.E.P. Effects of beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) supplementation on muscle mass, function, and other outcomes in patients with cancer: A systematic review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 1623–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhao, A.; He, J. Effect of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) on the Muscle Strength in the Elderly Population: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 914866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekala, J.; Patkowska-Sokoła, B.; Bodkowski, R.; Jamroz, D.; Nowakowski, P.; Lochyński, S.; Librowski, T. L-carnitine-metabolic functions and meaning in humans life. Curr. Drug Metab. 2011, 12, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.L.; Simmons, P.A.; Vehige, J.; Willcox, M.D.; Garrett, Q. Role of carnitine in disease. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malaguarnera, M.; Risino, C.; Gargante, M.P.; Oreste, G.; Barone, G.; Tomasello, A.V.; Costanzo, M.; Cannizzaro, M.A. Decrease of serum carnitine levels in patients with or without gastrointestinal cancer cachexia. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 4541–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Luk, H.; Lombard, J.R.; Dunn-Lewis, C.; Volek, J.S. Chapter 39—Physiological Basis for Creatine Supplementation in Skeletal Muscle. In Nutrition and Enhanced Sports Performance; Bagchi, D.S.N., Sen, K.C., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- das Neves, W.; Alves, C.R.R.; de Souza Borges, A.P.; de Castro, G., Jr. Serum Creatinine as a Potential Biomarker of Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 625417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candow, D.G.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Forbes, S.C.; Fairman, C.M.; Gualano, B.; Roschel, H. Creatine supplementation for older adults: Focus on sarcopenia, osteoporosis, frailty and Cachexia. Bone 2022, 162, 116467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, E.; Beckwee, D.; Delaere, A.; De Breucker, S.; Vandewoude, M.; Bautmans, I. Nutritional interventions to improve muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance in older people: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorjao, R.; Dos Santos, C.M.M.; Serdan, T.D.A.; Diniz, V.L.S.; Alba-Loureiro, T.C.; Cury-Boaventura, M.F.; Hatanaka, E.; Levada-Pires, A.C.; Sato, F.T.; Pithon-Curi, T.C.; et al. New insights on the regulation of cancer cachexia by N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 196, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlory, C.; Calder, P.C.; Nunes, E.A. The Influence of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Skeletal Muscle Protein Turnover in Health, Disuse, and Disease. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Bo, C.; Bernardi, S.; Marino, M.; Porrini, M.; Tucci, M.; Guglielmetti, S.; Cherubini, A.; Carrieri, B.; Kirkup, B.; Kroon, P.; et al. Systematic Review on Polyphenol Intake and Health Outcomes: Is there Sufficient Evidence to Define a Health-Promoting Polyphenol-Rich Dietary Pattern? Nutrients 2019, 11, 1355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Egert, S.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Seiberl, J.; Kürbitz, C.; Settler, U.; Plachta-Danielzik, S.; Wagner, A.E.; Frank, J.; Schrezenmeir, J.; Rimbach, G.; et al. Quercetin reduces systolic blood pressure and plasma oxidised low-density lipoprotein concentrations in overweight subjects with a high-cardiovascular disease risk phenotype: A double-blinded, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rauf, A.; Imran, M.; Khan, I.A.; Ur-Rehman, M.; Gilani, S.A.; Mehmood, Z.; Mubarak, M.S. Anticancer potential of quercetin: A comprehensive review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 2109–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Song, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; Xing, N. Quercetin in prostate cancer: Chemotherapeutic and chemopreventive effects, mechanisms and clinical application potential (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 2659–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giordano, A.; Tommonaro, G. Curcumin and Cancer. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdura, S.; Cuyàs, E.; Ruiz-Torres, V.; Micol, V.; Joven, J.; Bosch-Barrera, J.; Menendez, J.A. Lung Cancer Management with Silibinin: A Historical and Translational Perspective. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binienda, A.; Ziolkowska, S.; Pluciennik, E. The Anticancer Properties of Silibinin: Its Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Effect in Breast Cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 1787–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, K.; Kumar, S.; Dhar, D.; Agarwal, R. Silibinin and colorectal cancer chemoprevention: A comprehensive review on mechanisms and efficacy. J. Biomed. Res. 2016, 30, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prasad, R.R.; Paudel, S.; Raina, K.; Agarwal, R. Silibinin and non-melanoma skin cancers. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2020, 10, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch-Barrera, J.; Sais, E.; Cañete, N.; Marruecos, J.; Cuyàs, E.; Izquierdo, A.; Porta, R.; Haro, M.; Brunet, J.; Pedraza, S.; et al. Response of brain metastasis from lung cancer patients to an oral nutraceutical product containing silibinin. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 32006–32014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sahin, I.; Bilir, B.; Ali, S.; Sahin, K.; Kucuk, O. Soy Isoflavones in Integrative Oncology: Increased Efficacy and Decreased Toxicity of Cancer Therapy. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 1534735419835310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, D.P.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.M.; Li, H.B. Natural Polyphenols for Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Nutrients 2016, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ren, B.; Kwah, M.X.; Liu, C.; Ma, Z.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Ding, L.; Xiang, X.; Ho, P.C.; Wang, L.; Ong, P.S.; et al. Resveratrol for cancer therapy: Challenges and future perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2021, 515, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.J.; Bao, J.L.; Chen, X.P.; Huang, M.; Wang, Y.T. Alkaloids isolated from natural herbs as the anticancer agents. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 485042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, A.; Vanecha, R.; Patel, J.; Patel, D.; Shah, U.; Bambharoliya, T. Development of Natural Bioactive Alkaloids: Anticancer Perspective. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hassan, H.; Rompola, M.; Glaser, A.W.; Kinsey, S.E.; Phillips, R.S. Systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the efficacy and safety of probiotics in people with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 2503–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.Y.; Jeong, J.K.; Lee, Y.E.; Daily, J.W., 3rd. Health benefits of kimchi (Korean fermented vegetables) as a probiotic food. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hutterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roeland, E.J.; Bohlke, K.; Baracos, V.E.; Bruera, E.; Del Fabbro, E.; Dixon, S.; Fallon, M.; Herrstedt, J.; Lau, H.; Platek, M.; et al. Management of Cancer Cachexia: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2438–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.A.; Splenser, A.; Guillory, B.; Luo, J.; Mendiratta, M.; Belinova, B.; Halder, T.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.P.; Garcia, J.M. Ghrelin prevents tumour- and cisplatin-induced muscle wasting: Characterization of multiple mechanisms involved. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2015, 6, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Chen, P.; Zhao, L.; Chen, S. Acylated and unacylated ghrelin relieve cancer cachexia in mice through multiple mechanisms. Chin. J. Physiol. 2020, 63, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Geppert, J.; Walth, A.A.; Terrón Expósito, R.; Kaltenecker, D.; Morigny, P.; Machado, J.; Becker, M.; Simoes, E.; Lima, J.; Daniel, C.; et al. Aging Aggravates Cachexia in Tumor-Bearing Mice. Cancers 2021, 14, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flurkey, K.M.; Currer, J.; Harrison, D.E.; Fox, J.G.; Davisson, M.T.; Quimby, F.W.; Barthold, S.W.; Newcomer, C.E.; Smith, A.L. Chapter 20—Mouse Models in Aging Research. In The Mouse in Biomedical Research, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 637–672. [Google Scholar]

| Strain | Tumor Model | Intervention A | Duration | Outcomes of Interest | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acids and Metabolites/Derivatives | |||||

| Amino Acids | |||||

| 3/4-wk-old male Wistar rats. | Walker 256 (breast CA). | Control diet or High-Leu diet (HLD) (3%). Arms: CD; HLD; TB; TB + HLD (n = 8–10). | 12 days. |

| [19] |

| NMRI mice (sex and age NR). | MAC 16 (colon CA). | PBS, Leu, IsoLeu, or valine (1 g/kg BW)/d by gavage. Initiated when mice lost 5% BW (12–15 days post-TI) Arms: TB; TB + Valine; TB + Leu; TB + IsoLeu. (n = 6). | 4–5 days. |

| [20] |

| 7–8 wks-old male CD2F1 mice. | C-26 (colon CA). | CD (8.7% Leu/g of PRO) or Leu chow [high (14.8% Leu/g of PRO) or low dose (9.6% Leu/g of PRO)]. Arms: CON; TB; TB + low; TB + high (n = 6). | 21 days. |

| [21] |

| 13-wk-old female Wistar rats. | Walker 256 (breast CA). | Isocaloric diets = CD (1.6% Leu) or HLD (3%). Arms: CD; HLD; TB; TB + HLD (TBL) (n = 6). | 21 days. |

| [22] |

| 13-wk-old male Wistar rats. | Walker-256 (breast CA). | HLD (4.6%) or CD (1.6% Leu) Isocaloric for 21 days. Arms: CD; HLD; TB; TB + HLD (TBL) (n = 10). | 21 days. |

| [23] |

| 12-wk-old Male Wistar rats. | Walker 256 (breast CA). | CD (18% PRO) or HLD diet: 18% PRO with 3% Leu B added. Arms: CD; HLD; TB; TB + HLD (TBL) (n = 6). | 18 days. |

| [24] |

| ꞵ-hydroxy ꞵ-methylbutyrate/Glycine | |||||

| Male NMRI mice (age NR). | MAC16 (colon CA). | EPA (0.6 g/kg/d), HMB (0.25 g/kg/d), both, or olive oil or PBS (CON) by gavage. Initiated 9 days after TI. Arms: CON; EPA; HMB; HMB + EPA (n = 6). | 9 days. |

| [25] |

| Male Wistar rats (age NR). | Yoshida ascites hepatoma. | 4% HMB-enriched chow or standard chow (CD). Initiated 16 days before TI and continued for 8 days. Arms: CD; HMB; TB; TB + HMB (n = 12–15). | 24 days. |

| [26] |

| 14-wk-old male CD2F1 mice. | C-26 (colon CA). | 1 g/kg/d of Glycine (Gly) or Saline in PBS via SC injections. Arms: CON + PBS; TB + PBS; TB + Gly (n = 12–16). | 21 days. |

| [27] |

| Carnitine | |||||

| 7/9-wk-old male BALB/c. | C-26 (colon CA). | Oral L-CAR at 4.5 mg/kg/d or 18 mg/kg/d or saline (2 mL). Initiated 12 days after TI. Arms: CON; TB CON; TB + CAR (n = 5–8). | 7 days. |

| [28] |

| 5-wk-old male Wistar Rats. | Yoshida ascites hepatoma. | Daily i.g. dose of CAR (1 g/kg of BW/d) or vehicle (corn oil). Arms: TB; TB + L-CAR (n = 8–24). | 7 days. |

| [29,30] |

| Creatinine | |||||

| Male Wistar rats (age NR). | Walker 256 (breast CA). | 8 g/L of CRE monohydrate in drinking water (1.0 ± 0.1 g/kg/d). Initiated 11 days before TI and maintained for 10 days after. Arms: CON; TB CON; TB + CRE (n = 10). | 21 days. |

| [31] |

| 7-wk-old male BABL/c. | C-26 (colon CA). | Daily i.p. injection of CRE (125 mM) in PBS for 7 days. Arms: CON; TB CON; TB + CRE (n = 6). | 7 days. |

| [32] |

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids | |||||

| PUFAs Alone | |||||

| 10-wk-old BDIX rats. | DHD/K12 colon CA, PROb clone. | CD = 12% peanut oil + 3% rapeseed oil or Fish Oil (FO): 8% peanut oil + 2% rapeseed oil + 5% FO. Some were pair fed (PF) and the rest fed ad libitum. Initiated 6 wks before TI and continued for 11 days. Arms: CD; TB + CD; CD + PF; FO; TB + FO; FO + PF (n = 10–18). | 53 days. |

| [33] |

| Male Fischer 344 rats (age NR). | Ward (colon CA). | Walnut (4.5 ꞷ-6/ꞷ-3 ratio) or CON (23.3 ꞷ-6/ꞷ-3 ratio) diet for a variable duration C. Pair feeding (PF) began on day 31. The walnut diet was initiated on day 0 or the day after TI (day 21). Arms: CON diet; CON + walnut crossover; walnut diet (n = 6). Subgroups of Non TB; Non TB + PF; and TB in all 3 groups. | 49–70 days. |

| [34] |

| 7-wk-old C57BL/6J mice. | LLC (lung CA). | 400 mg/kg of EPA-PL (EPA- enriched phospholipids) in corn oil or corn oil alone (CON) via gavage once a day. Initiated 8 days after TI. Arms: CON; TB CON; TB + EPA-PL (n = 8). | 20 days. |

| [35] |

| PUFAs with Antioxidants | |||||

| 7–8 wks old male CD2F1. | C-26 (colon CA). | Normal diet (AIN93-M) + 22 g of FO (6.9 g EPA and 3.1 g DHA), 16 g/kg/d Leu, and/or HPD (151 g casein/kg/d). Arms: CON; TB; TB + HPD + Leu; TB + FO; TB + FO + HPD; TB + FO + Leu + HPD (n = 10–40). | 20 days. |

| [36] |

| 6–7 wks old male BALB/cByJ mice. | Line-1 lung CA. | 20 mg FO (EPA and DHA) and/or 0.69 mg selenium yeast (SY) with standard diet. Arms: CON; TB; TB + FO; TB + SY; TB + FO + SY (n = 6–10). | 42 days. |

| [37] |

| Polyphenols | |||||

| Quercetin | |||||

| 15/18-wk-old male C57BL or ApcMin/+. | Colon CA. | 25 mg/kg/d of Q or vehicle (tang juice + water) via gavage. Treatment started when mice lost 1–4% BW. Arms: C57BL/6; C57BL/6 + Q; TB CON, TB + Q (n = 5–8). | 21 days. |

| [38] |

| 8-wk-old male CD2F1 F1 mice. | C-26 (colon CA). | Regular or Q-enriched (250 mg/kg) chow. Expected daily intake of 35 mg/kg). Arms: CD; TB + CD; TB + Q (n = 10). | 21 days. |

| [39] |

| 14-wk-old male CD2F1 mice. | C-26 (colon CA). | Fluorouracil (5 FU) 30 mg/kg of lean mass via i.p. with daily Q in propylene glycol (50 mg/kg of BW) or vehicle (propylene glycol) via gavage. Initiated 10 days after TI. Arms: CON; TB CON; TB + 5 FU; TB + 5 FU + Q (n = 5). | 5 days. |

| [40] |

| Curcumin | |||||

| Male Wistar rats (age NR). | Yoshida ascites hepatoma. | Curcumin (Curc) 20 mg/kg/d or vehicle i.p. Initiated 1 day after TI. Arms: CON; CON + Curc; TB CON; TB + Curc (n = 6–10). | 6 days. |

| [41] |

| 6–7-wks-old male athymic mice. | MAC16 (colon CA). | 100 mg/kg/d or 250 mg/kg/d of Curc or vehicle orally. Initiated 10–12 days after TI (5–7% WL). Arms: CON; TB; TB + 100 mg/kg; TB + 250 mg/kg (n = 5). | 21 days. |

| [42] |

| 6-wk-old male BALB/c mice. | C-26 (colon CA). | Daily i.p. injection of 200 mg/kg of curcumin or PBS. Initiated 9 days after TI. Arms: CON; CON + Curc; TB CON; TB + Curc (n = 12–13). | 7 days. |

| [43] |

| 10-wk-old female BALB/c. | LPO7 (lung CA). | 1 mg/kg/d of curcumin, 20 mg/kg/d of resveratrol, or saline via i.p. Initiated 15 days after TI. Arms: TB CON; TB + Curc; TB + Resv (n = 10). | 15 days. |

| [44] |

| 6-wk-old female. BALB/c mice. | 4T1 (breast CA). | “0.2 mL Curcumin solution of 150 mg/dL” or equal amount of saline by gavage. Initiated 1 wk after TI. Arms: CON + Saline; TB + CON; TB + Curc (n = 8). | 28 days. |

| [45] |

| Silibinin | |||||

| 6–8 wks-old athymic female mice. | Human pancreatic CA S2-013. | 200 mg/kg/d silibinin (SLI) or solvent control (form of administration NR). Initiated 7 days after TI. Arms: CON; TB CON; TB + SLI (n = 8). | 18 days. |

| [46] |

| 5-wk-old male C57BL/6. | LLC (lung CA). | Cisplatin (DDP) 4 mg/kg or saline i.p. across 7 days (4 injections) + i.g. 0.3% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, silibinin (SLI) 40 mg/kg/d (low dose), 0 or 80 mg/kg/d (high dose). Initiated 7 days after TI. Arms: CON; TB CONC; TB + DDP; TB + DDP + SLI 40; TB + DDP + SLI 80 (n = 5). | 8 days. |

| [47] |

| Isoflavones | |||||

| 8-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice. | LLC (lung CA). | CD with or without Isoflavones (obtained from soya flavone). Arms: CD; CON + Isoflavone; TB; TB + Isoflavone (n = 5–6). | 21 days. |

| [48] |

| Resveratrol (Resv) | |||||

| 5-wk-old male Wistar rats and 12 wk old C57Bl/6 mice. | Yoshida ascites hepatoma or LLC (lung CA). | Resveratrol 1, 5, or 25 mg/kg of BW or 3 mg/kg + 1 mL of FO i.g. Arms: CON; CON + Resv; TB CON; TB + Resv +/− FO (n = NR). | 7 days. |

| [49] |

| 8–10-wks-old female CD2F1 mice. | C-26 (colon CA). | Resveratrol (100–500 mg/kg/d) or control vehicle by gavage. Initiated on the 6th day of TI. Arms: CON; CON + Resv 100–500 mg/kg; TB CON; TB + Resv 100–500 mg/kg (n = 4–8). | 11 days. |

| [50] |

| Alkaloids | |||||

| 6-wk-old male BALB/c mice. | C-26/ clone 20 (colon CA). | Coptidis rhizoma (CR) 1 or 2% or berberine (BB) (0.1–0.4%) in standard diet. Began 4 days prior to TI. Arms: CON; TB + CR (1–2%); TB; TB + BB (0.1–0.4%) (n = 6–9). | 18 days. |

| [51] |

| Male BALB/c mice (age NR). | C-26 (colon CA). | Matrine (M) (50 mg/kg/d) or sophocarpine (SPH) (50 mg/kg/d) in 0.2 mL of Saline i.p. Initiated 12 days after TI. Arms: CON + Saline; TB + Saline; TB + M; TB + SPH (n = 10). | 5 days. |

| [52] |

| 5-wk-old male Wistar rats. | Yoshida ascites hepatoma. | Daily i.g. dose of theophylline (TPH), 50 mg/kg BW dissolved in corn oil or corn oil alone. Arms: CON; TB; TB + TPH (n = 6). | 7 days. |

| [53] |

| Probiotics | |||||

| 8-wk-old (sex NR). ApcMin/+ mice. | Colon CA. | L. reuteri (3.5 × 105 organisms/mouse/d) in drinking water, replaced 2×/wk. Initiated 8 wks of age. Arms: TB; TB + L. reuteri (n = 6). | 15 wks. |

| [54] |

| 6-wk-old male BALB/c mice. | C-26 (colon CA). | Probiotic-enriched Kimchi-diet (5.1 mg/kg/d) or normal diet (100 g/wk). Pellets were changed weekly. Arms: CON; TB; TB + kimchi diet (n = 10). | 21 days. |

| [55] |

| Purpose | Design | Intervention | Efficacy Outcomes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acids and Metabolites/Derivatives | ||||

| HMB | ||||

| To assess the efficacy of HMB + Arg + Gln in cancer cachexia. | * Cohort: stage IV solid tumors. Cachexia I/E: WL > 5% (time frame unspecified). | EXP: HMB (3 g/d), Arg (14 g/d), Gln (14 g/d) juice. CON: isocaloric (180 kcal/d), isonitrogenous (7.19 g N/d) with non-essential amino acids.

| Body Weight: No effect by time or treatment in intent-to-treat analysis. Muscle Mass: FFM change (BIA) was greater at Wk-4 in EXP (+1.12 kg) vs. CON (−1.34 kg) with a trend at Wk-24: EXP (+1.60 kg) vs. CON (+0.48 kg). PR-QOL: No changes or group difference in SF-36 or FACT-G. Physical Function: Not measured. | [56] |

| To assess the efficacy of HMB + Arg + Gln on prevention of LBM loss in cancer cachexia. | * Cohort: stage III/IV solid or metastatic cancer of any initial stage. Cachexia I/E: 2–10% WL over prior 3 mos. | EXP: HMB (3 g), Arg (14 g), Gln (14 g); bid. CON: isonitrogenous, isocaloric mixture; bid.

| Body Weight: No group difference in change. Muscle Mass: No group difference in LBM change by BIA, skin fold, or body plethysmography. PR-QOL: No group difference in Schwartz Fatigue score. Physical Function: Not measured. | [57] |

| Carnitine | ||||

| Determine the effect of carnitine on fatigue in cancer patients with carnitine deficiency. | * Cohort: advanced cancer with fatigue and carnitine deficiency. Cachexia I/E: none and did not report BW at Pre or BW change. | EXP: L-carnitine 1 g in 10 mL syrup. CON: syrup (formulation not provided).

| Body Weight: Not measured. Muscle Mass: Not measured. PR-QOL: No group difference in FACT-An or LASA change (significance of within-group change NR; however, after controlling for baseline age and fatigue, FACT-An fatigue improved in L-carnitine vs. CON) after blinded phase. Physical Function: No group difference in KPS or FACT-An Functional Well-being sub-category after blinded phase. | [58] |

| Determine the effect of carnitine treatment in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. | * Cohort: unresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cachexia I/E: none but 90% had WL >10% in prior 6 mos. | EXP: L-carnitine “oral formulation” 4 g/d. CON: described as “identically formulated”.

| Body Weight: L-Carnitine gained weight vs. placebo. Muscle Mass: BIA was measured but only body cell mass and body fat were reported. PR-QOL: Global QOL and GI symptoms from EORTC QLQ-C30 improved in L-carnitine vs. CON; no difference between groups in BFI. Physical Function: Not measured. | [59] |

| Efficacy and safety of L-carnitine in advanced cancer. | Cohort: solid tumors undergoing anti-cancer treatment. Cachexia I/E: none, but patients had to display fatigue and/or elevated ROS. | L-carnitine: 6 g/d (2 g tid); (n = 2 M/10 F). Assessed at 2- and 4-wks. | Body Weight: No change. Muscle Mass: LBM (BIA) increased at 2- (~1.7 kg) and 4-wks (~2.4 kg) vs. baseline. PR-QOL: MFSI-SF QoL “General Scale”, QoL-OS (all sub-scales), and EQ5DVAS improved at 4-wks vs. baseline. Physical Function: MFSI-SF QoL “Physical Scale” and QoL-OS “Physical Scale” improved at 4-wks; no change in HGS. | [60] |

| Creatine | ||||

| Evaluate the effect of creatine on muscle function and QOL in patients with CRC. | * Cohort: CRC Stage III/IV undergoing chemotherapy. Cachexia I/E: none, but cachexia was a key feature of the background (results state none had >10% WL at Baseline). | EXP: creatine monohydrate. CON: cellulose

| Body Weight: Increased in CON only. Muscle Mass: No change in MAMC or body cell mass (BIA) for either group (did not report lean mass from BIA). PR-QOL: No change in EORTC QLQ-C30 for either group. Physical Function: HGS increased for non-dominant hand in EXP; no change for either group in knee ext or hip flex. | [61] |

| To test the efficacy of creatine as a supportive care strategy in patients with cancer cachexia. | * Cohort: incurable malignancy (except primary brain tumor). Cachexia I/E: WL ≥ 5 lb in 2 mos, and/or estimated caloric intake < 20 kcals/kg/d and weight perception A. | EXP: creatine monohydrate. CON: “identical-appearing placebo”

| Body Weight: No change in either group. Muscle Mass: No change in BIA parameters for either group (assessed in small sub-set). PR-QOL: No change in FAACT or linear analog self-assessment for either group. Physical Function: No change in HGS for either group. | [62] |

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids | ||||

| PUFAs Alone | ||||

| Study the effect of fish oil in weight-losing pancreatic cancer patients. | Cohort: unresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cachexia I/E: none. | Fish oil: 2 g/d increased weekly by 2 g to a max dose of 16 g/d.

| Body Weight: Weight gain of 0.3 kg/mo at 3-mos was significantly different vs. rate of change at baseline (−2.9 kg/mo). Muscle Mass: No change in MAMC. PR-QOL: Not measured. Physical Function: Not measured. | [63] |

| To evaluate the acceptability and effect of oral EPA in weight-losing cancer patients. | Cohort: pancreas or ampulla (unresectable). Cachexia I/E: none. | EPA: initially 1 g/d increased to 6 g/d over 1 st 4 wks, then 6 g/d for remaining 8 wks; (n = 12 M/14 F). Assessed at 4, 8, and 12 wks. | Body Weight: Baseline WL averaged 13%; rate of loss was reduced at 4–12 wks. Muscle Mass: Not measured. PR-QOL: Not measured. Physical Function: No change in WHO performance status. | [64] |

| Examine the efficacy of fish oil to slow weight loss and improve QOL in cancer cachexia. | Cohort: malignancy not amenable to curative treatment. Cachexia I/E: WL > 2% prior 1 mo. | Fish oil: started at 0.3 g/kg/d fish oil, reduced to 0.15 g/kg/d after 13 patients; (n = 29 M/14 F).

| Body Weight: Number of days receiving fish oil was correlated with weight gain for those taking the capsules for ≥30 d. Muscle Mass: Not measured. PR-QOL: No change in FAACT or FACT-G. Physical Function: Not measured. | [66] |

| Study the effects of fish oil and/or melatonin in cancer cachexia. | Cohort: metastatic or locally advanced GI cancer not amenable to curative or standard palliative treatment. Cachexia I/E: >10% WL in prior 6 mos. | Fish oil: 30 mL/d (EPA 4.9 g + DHA 3.2 g); 4 wks. Melatonin: 18 mg/d; 4 wks. Cross-over: After initial 4 wks of treatment, all patients consumed both supplements for an additional 4 wks (all received diet counseling) Fish Oil (n = 7 M/6 F), Melatonin (n = 7 M/4 F). | Body Weight: No group difference in weight change at Wk 4 or Wk 8. Muscle Mass: Not measured. PR-QOL: No group difference in EORTC QLQ-C30 Global QoL. Physical Function: Baseline EORTC QLQ-C30 physical function was lower in Melatonin and increased at Wk 4 for Fish Oil; no group difference in KPS change. | [67] |

| To assess the effects of EPA on weight and LBM in cancer cachexia. | * Cohort: GI or lung. Cachexia I/E: ≥5% loss of pre-illness stable weight. | EXP: EPA 1 g in diester oil (2 or 4 g EPA/d). CON: MCT 1 g/d in diester oil.

| Body Weight: Trend for between-group difference in change (relative to CON) at wk 8: 2 g (+1.2 kg) vs. 4 g (+0.3 kg). Muscle Mass: No group difference in LBM (BIA) change. PR-QOL: No group difference in EORTC QLQ-C30 for appetite. Physical Function: Physical function (EORTC QLQ-C30) improved in EPA 2 g vs. others; no group difference in KPS. | [68] |

| To assess the effects of largehead atractylodes rhizome in alleviating cytokine-mediated symptoms in cancer cachexia. | Cohort: advanced, unresectable gastric cancer. Cachexia I/E: diminished or absent appetite (undefined). | EXP1: Atractylenolide I (1.32 g/d; 6 ml bid). EXP2: Fish Oil (0.45 g/d; 4 pills bid).

| Body Weight: No group difference in rate of weight change. Muscle Mass: No group difference in rate of MAMC change. PR-QOL: Greater rate of VAS appetite increase at 3 and 7 wks in EXP1 vs. EXP2. Physical Function: Greater rate of KPS increase at 3 and 7 wks in EXP1 vs. EXP2. | [69] |

| To test the efficacy of echium oil as a supportive care strategy in HNC in systemic therapy. | * Cohort: HNC initiating radio-chemotherapy. Cachexia I/E: none but average WL was 2.4% at baseline and 30% had ≥5% 6-mo WL at baseline. | EXP: 7.5 mL echium oil (235 ± 30 mg/mL ALA + 95 ± 13 mg/mL ALA SDA + 79 ± 10 mg/mL GLA) bid. CON: 7.5 mL sunflower oil (no ꞷ-3-FA) bid.

| Body Weight: No group difference. Muscle Mass: No group difference in FFM and LBM (DXA) decrease; no change by BIA (DXA and BIA assessed at Wk 4). PR-QOL: EORTC QLQ-C30 and -H&N35; no within-group changes or between-group difference. Physical Function: no within-group changes or between-group difference in HGS change. | [70] |

| Assess if fish oil has beneficial effects on weight loss in lung cancer patients. | * Cohort: advanced lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Cachexia I/E: none. | EXP: “Fish Oil” EPA 0.1 g/mL + DHA 0.12 g/mL. CON: “Rapeseed Oil” ALA 0.078 g/mL.

| Body Weight: No WL in either group. Muscle Mass: No change in MAMC for either group. PR-QOL: No change in EORTC QLQ-C30 or Lung Cancer-13 for either group. Physical Function: No change in HGS for either group. | [71] |

| Compare MPL and fish oil on weight, appetite, and QOL in pancreatic cancer patients with cachexia. | Cohort: pancreas Cachexia I/E: WL ≥ 5% since diagnosis (Building on their prior pilot study [72]). | EXP1: “MPL” (35% ꞷ-3-FA phospholipids + 65% neutral lipids). EXP2: “Fish oil” (60% EPA/DHA + 40% MCT)

| Body Weight: No change in either group. Muscle Mass: “Muscle mass” (undefined) not different between groups at Wk 6. PR-QOL: EORTC QLQ-C30 (no change in either group), PAN26 (hepatic function improved in MPL only). Physical Function: Not measured. | [73] |

| PUFAs with Antioxidants | ||||

| Investigate the effect of PUFA’s on T-cell subsets and cytokine production in cancer patients with or without malnutrition. | * Cohort: solid tumors. Cachexia I/E: none but groups were divided into well-nourished and malnourished B. | EXP: “Fish oil” EPA 170 mg, DHA 115 mg + Vitamin E 200 mg; 6 pills tid. CON: “sugar tablets”; 6 pills tid.

| Body Weight: No change in either group. Muscle Mass: Not measured. PR-QOL: Not measured. Physical Function: Increased KPS in malnourished EXP patients only. | [74] |

| Determine whether fish oil at high doses improves symptoms in advanced cancer patients with weight loss and anorexia. | * Cohort: advanced cancer. Cachexia I/E: anorexia (>3 on VAS) + >5% WL from pre-illness weight. | EXP: “Fish Oil” 1000 mg = EPA 180 mg, DHA 120 mg, and vitamin E 1 mg. CON: 1000 mg olive oil

| Body Weight: No group difference in change. Muscle Mass: No group difference in FFM (BIA) change. PR-QOL: No group difference in VAS change for appetite, nausea, tiredness, or overall well-being. Physical Function: No group difference in KPS change. | [75] |

| Assess the effects of a fatty acid and antioxidant enriched supplement on weight, body composition, diet, and QOL in weight losing pancreatic cancer patients. | * Cohort: unresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cachexia I/E: WL > 5% in prior 6 mos. | EXP: 16 g PRO, 6 g fat, 1.1 g. EPA and antioxidants [Vitamins A 2524 IU, E 75 IU, C 105 mg, and selenium 17.5 mg]); 2 cans/d (620 kcals/d). CON: 16 g PRO, 6 g fat; 2 cans/d (620 kcals/d)

Separate post-hoc analysis for compliant (≥1.5 cans/d) vs. non-compliant (<1.5 cand/d). | Body Weight: No group difference in change. Supplement intake correlated with weight gain in EXP; trend for weight gain over 8 wks in compliant vs. WL in non-compliant. Muscle Mass: No group difference in LBM (BIA) change. Supplement intake correlated with LBM gain in EXP. PR-QOL: Supplement intake correlated with EuroQol EQ5Dindex increase in EXP; trend for better EORTC QLQ-C30 over 8 wks in compliant vs. non-compliant. Physical Function: Not measured. | [76] |

| Polyphenols | ||||

| Curcumin | ||||

| Determine the effect of curcumin in HNC cachexia. | * Cohort: HNC or nasopharyngeal receiving chemo- or radiotherapy + feeding tube. Cachexia I/E: >5% WL in prior 6 mos or 2–5% WL + BMI < 20 kg/m2. | EXP: Curcumin (2000 mg bid: 4 capsules of 500 mg each). CON: matching placebo “made from probiotics” (2000 mg bid: 4 capsules of 500 mg each).

| Body Weight: NR, but BMI change was not different between groups. Muscle Mass: LBM (BIA) change after 8 wks was significantly different between curcumin (+0.46 kg) and CON (−1.05 kg). PR-QOL: Not measured. Physical Function: No change in HGS for either group. | [77] |

| Evaluate the effect of curcumin on body composition in cancer cachexia. | * Cohort: advanced solid tumors, undergoing systemic treatment. Cachexia I/E: WL ≥ 5% in 12 mos or BMI < 20 kg/m2 + 3 criteria C. | EXP: Curcumin (800 mg bid). CON: Corn starch (800 mg bid).

| Body Weight: No within- or between-group differences. Muscle Mass: Skeletal muscle mass (BIA), no within- or between-group differences. PR-QOL: Not measured. Physical Function: No within- or between-group differences in HGS. | [78] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caeiro, L.; Gandhay, D.; Anderson, L.J.; Garcia, J.M. A Review of Nutraceuticals in Cancer Cachexia. Cancers 2023, 15, 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153884

Caeiro L, Gandhay D, Anderson LJ, Garcia JM. A Review of Nutraceuticals in Cancer Cachexia. Cancers. 2023; 15(15):3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153884

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaeiro, Lucas, Devika Gandhay, Lindsey J. Anderson, and Jose M. Garcia. 2023. "A Review of Nutraceuticals in Cancer Cachexia" Cancers 15, no. 15: 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153884

APA StyleCaeiro, L., Gandhay, D., Anderson, L. J., & Garcia, J. M. (2023). A Review of Nutraceuticals in Cancer Cachexia. Cancers, 15(15), 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153884