Supportive Care: The “Keystone” of Modern Oncology Practice

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Definition of Supportive Care

- ❖

- Supportive care aims to maintain (or improve) quality of life and to ensure that people with cancer can achieve the maximum benefit from their anticancer treatment;

- ❖

- Supportive care is relevant throughout the continuum of the cancer experience, from diagnosis through treatment to post-treatment care (and encompasses cancer survivorship and palliative and end-of-life care);

- ❖

- Supportive care involves a coordinated, person-centric, and holistic (whole-person) approach, which should be guided by the individual’s preferences and should include the appropriate support of their family and friends;

- ❖

- Supportive care (as outlined) is a basic right for all people with cancer, irrespective of their personal circumstances, their type of cancer, their stage of cancer, or their anticancer treatment. It should be available in all cancer centres, and other medical facilities that routinely manage people with cancer.

- Multidisciplinary care:

- -

- Patients should have access to palliative care specialists while receiving anticancer therapy;

- -

- Patients should have access to high-quality nursing, social work support, financial counselling, and spiritual counselling;

- -

- Cooperative groups and institutional review boards should encourage standard processes to educate patients so that they understand the goals of anticancer therapy, the importance of symptom assessment, and the role of symptom management within the clinical trial.

- Documentation:

- -

- For trials with a significant best supportive care component, institutional review boards should review trial protocols for documentation of supportive care interventions;

- -

- For trials with a significant best supportive care component, the delivery of supportive care within a clinical trial should be documented in a standard way for all patients on that trial;

- -

- Journal editors should ask for a clear description of what best supportive care entailed in reports of trials with a significant best supportive care component.

- Symptom assessment:

- -

- Symptoms should be assessed at baseline and regularly throughout the trial;

- -

- Symptoms should be assessed using concise, globally accessible, and validated tools.

- In trials in which patients are enrolled in a best supportive care group vs. an intervention group, the intervals between symptom assessments should be identical in both groups;

- Symptom management:

- -

- Symptom control should be conducted in line with evidence-based guidelines;

- -

- Clinical trial protocols should encourage guideline-based symptom control.

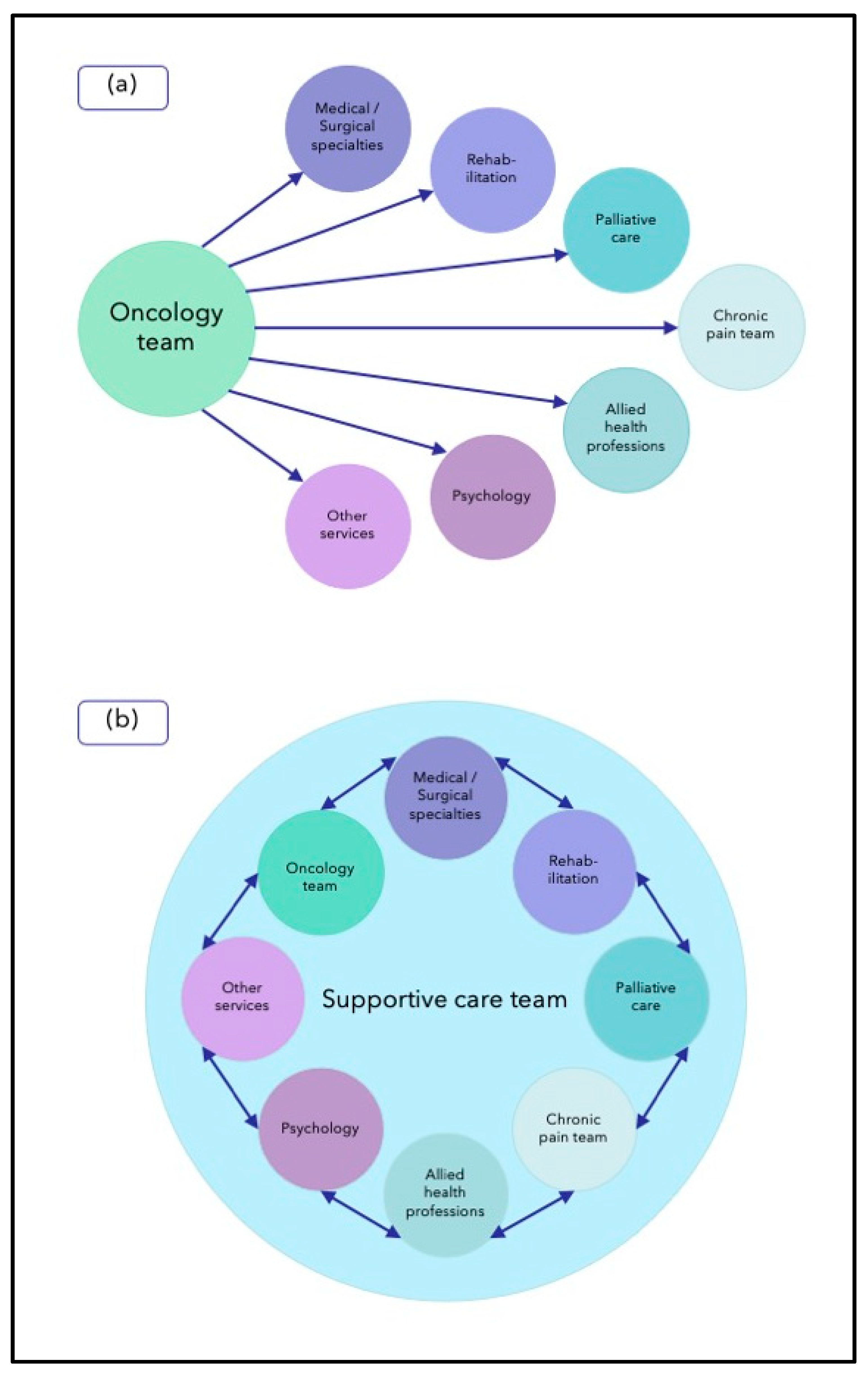

3. Models of Supportive Care

- Management of cancer-related symptoms/problems:

- -

- Pain;

- -

- Other symptoms.

- Management of cancer treatment-related symptoms/problems:

- -

- Prophylaxis, e.g., antiemetics to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting;

- -

- Treatment.

- Coordinating management of co-morbidities with other specialties;

- Psychological support:

- -

- Patient;

- -

- Carers (children).

- Nutritional support;

- Prehabilitation;

- Rehabilitation;

- Social care:

- -

- Advocacy;

- -

- “Financial toxicity”.

- Palliative care:

- -

- “Early palliative care”;

- -

- End-of-life care/bereavement care.

- Survivorship care;

- Integrative therapies.

- ❖

- Integrated supportive care team/service (see Figure 1);

- ❖

- Consolidated leadership;

- ❖

- Collaborative teamwork;

- ❖

- Streamlined care (as a result of collaborative teamwork);

- ❖

- Universal referral of cancer patients; *

- ❖

- Systematic screening—to assess unmet supportive care needs, guide supportive care interventions, and facilitate timely supportive care interventions;

- ❖

- Tailored specialist involvement (as a result of systematic screening);

- ❖

- Consistent messaging (as a result of collaborative teamwork)

4. Rationale and Evidence for Supportive Care

5. Supportive Care Versus Palliative Care

- Includes prevention, early identification, comprehensive assessment, and management of physical issues, such as pain and other distressing symptoms, psychological distress, spiritual distress, and social needs. Whenever possible, these interventions must be evidence based;

- Provides support to help patients live as fully as possible until death by facilitating effective communication, helping them and their families determine goals of care;

- Is applicable throughout the course of an illness, according to the patient’s needs;

- Is provided in conjunction with disease-modifying therapies whenever needed;

- May positively influence the course of illness;

- Intends neither to hasten nor to postpone death, affirms life, and recognises dying as a natural process;

- Provides support to the family and caregivers during the patient’s illness, and in their own bereavement;

- Is delivered recognising and respecting the cultural values and beliefs of the patient and family;

- Is applicable throughout all healthcare settings (place of residence and institutions) and in all levels (primary to tertiary);

- Can be provided by professionals with basic palliative care training;

- Requires specialist palliative care with a multiprofessional team for referral of complex cases.

6. Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)

7. Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hui, D.; De La Cruz, M.; Mori, M.; Parsons, H.A.; Kwon, J.H.; Torres-Vigil, I.; Kim, S.H.; Dev, R.; Hutchins, R.; Liem, C.; et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care”, “best supportive care”, “palliative care”, and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 659–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, N. Best supportive care: A euphemism for no care or a standard of good care? Semin. Oncol. 2011, 38, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boyd, K.; Moine, S.; Murray, S.A.; Bowman, D.; Brun, N. Should palliative care be rebranded? BMJ 2019, 364, l881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jordan, K.; Aapro, M.; Kaasa, S.; Ripamonti, C.I.; Scotté, F.; Strasser, F.; Young, A.; Bruera, E.; Herrstedt, J.; Keefe, D.; et al. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, R.; Davies, A.; Cooksley, T.; Gralla, R.; Carter, L.; Darlington, E.; Scotté, F.; Higham, C. Supportive care: An indispensable component of modern oncology. Clin. Oncol. (R Coll. Radiol.) 2020, 32, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer Home Page. Available online: https://mascc.org (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- National Cancer Institute. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms: Supportive Care. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/supportive-care (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Cherny, N.I.; Abernethy, A.P.; Strasser, F.; Sapir, R.; Currow, D.; Zafar, S.Y. Improving the methodologic and ethical validity of best supportive care studies in oncology: Lessons from a systematic review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5476–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.Y.; Currow, D.C.; Cherny, N.; Strasser, F.; Fowler, R.; Abernethy, A.P. Consensus-based standards for best supportive care in clinical trials in advanced cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, e77–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Service England. Enhanced Supportive Care. Integrating Supportive Care in Oncology (Phase 1: Treatment with Palliative Intent). Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ca1-enhncd-supprtv-care-guid.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Haun, M.W.; Estel, S.; Rücker, G.; Friederich, H.C.; Villalobos, M.; Thomas, M.; Hartmann, M. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, Cd011129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, R.; Laird, B.J.A.; Minton, O.; Monnery, D.; Ahamed, A.; Boland, E.; Droney, J.; Vidrine, J.; Leach, C.; Scotté, F.; et al. The rise of supportive oncology: A revolution in cancer care. Clin. Oncol. (R Coll. Radiol.) 2023, 35, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radbruch, L.; De Lima, L.; Knaul, F.; Wenk, R.; Ali, Z.; Bhatnaghar, S.; Blanchard, C.; Bruera, E.; Buitrago, R.; Burla, C.; et al. Redefining palliative care-a new consensus-based definition. J. Pain. Symptom. Manag. 2020, 60, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Heung, Y.; Bruera, E. Timely palliative care: Personalizing the process of referral. Cancers 2022, 14, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.M.; Portenoy, R.K.; Weissman, D.E. Preface to the first edition. In Principles and Practice of Palliative Care and Supportive Oncology, 4th ed.; Berger, A., Shuster, J.L., Von Roenn, J.H., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; p. xii. [Google Scholar]

- Olver, I.; Keefe, D.; Herrstedt, J.; Warr, D.; Roila, F.; Ripamonti, C.I. Supportive care in cancer-a MASCC perspective. Support Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3467–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncology Nursing Society. Role of the oncology nurse navigator throughout the cancer trajectory. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2018, 45, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Virani, R.; Han, E.; Mazanec, P. Integration of palliative care in the role of the oncology advanced practice nurse. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2021, 12, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruinooge, S.; Pickard, T.A.; Vogel, W.; Hanley, A.; Schenkel, C.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Tetzlaff, E.; Rosenzweig, M.; Hylton, H.; Westin, S.N.; et al. Understanding the role of advanced practice providers in oncology in the United States. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2018, 45, 786–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emfield Rowett, K.; Christensen, D. Oncology nurse navigation: Expansion of the navigator role through telehealth. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 24, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Hoge, G.; Bruera, E. Models of supportive care in oncology. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2021, 33, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aapro, M.; Bossi, P.; Dasari, A.; Fallowfield, L.; Gascón, P.; Geller, M.; Jordan, K.; Kim, J.; Martin, K.; Porzig, S. Digital health for optimal supportive care in oncology: Benefits, limits, and future perspectives. Support Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4589–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marthick, M.; McGregor, D.; Alison, J.; Cheema, B.; Dhillon, H.; Shaw, T. Supportive care interventions for people with cancer assisted by digital technology: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, R.; Hall, S.; Sinclair, J.E.; Bond, C.; Murchie, P. Using technology to deliver cancer follow-up: A systematic review. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajkomar, A.; Dean, J.; Kohane, I. Machine learning in medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, N.H.; Crawford-Williams, F.; Crichton, M.; Yee, J.; Smith, T.J.; Koczwara, B.; Fitch, M.I.; Crawford, G.B.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Mahony, J.; et al. Unmet supportive care needs of people with advanced cancer and their caregivers: A systematic scoping review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 176, 103728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, M. The importance of planned dose of chemotherapy on time: Do we need to change our clinical practice? Oncologist 1998, 3, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuthbert, C.A.; Boyne, D.J.; Yuan, X.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Cheung, W.Y. Patient-reported symptom burden and supportive care needs at cancer diagnosis: A retrospective cohort study. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 5889–5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellas, O.; Kemp, E.; Edney, L.; Oster, C.; Roseleur, J. The impacts of unmet supportive care needs of cancer survivors in Australia: A qualitative systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Office of Cancer Survivorship: Definitions. Available online: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/definitions (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Monnery, D.; Benson, S.; Griffiths, A.; Cadwallader, C.; Hampton-Matthews, J.; Coackley, A.; Cooper, M.; Watson, A. Multi-professional-delivered enhanced supportive care improves quality of life for patients with incurable cancer. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2018, 24, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E.; Tavabie, S.; McGovern, C.; Round, A.; Shaw, L.; Bass, S.; Herriott, R.; Savage, E.; Young, K.; Bruun, A.; et al. Cancer centre supportive oncology service: Health economic evaluation. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 13, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, S.T.F.; Mellerick, A.; Akers, G.; Whitfield, K.; Moodie, M. Economic assessment of a new model of care to support patients with cancer experiencing cancer- and treatment-related toxicities. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e884–e892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonuzzo, A.; Vasile, E.; Sbrana, A.; Lucchesi, M.; Galli, L.; Brunetti, I.M.; Musettini, G.; Farnesi, A.; Biasco, E.; Virgili, N.; et al. Impact of a supportive care service for cancer outpatients: Management and reduction of hospitalizations. Preliminary results of an integrated model of care. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olver, I. (Ed.) The MASCC Textbook of Cancer Supportive Care and Survivorship, 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-331-990-989-9. [Google Scholar]

- ASCO Connection. ASCO Announces “Top 5” Advances in Modern Oncology. Available online: https://connection.asco.org/magazine/features/asco-announces-“top-5”-advances-modern-oncology (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Banke-Thomas, A.O.; Madaj, B.; Charles, A.; van den Broek, N. Social Return on Investment (SROI) methodology to account for value for money of public health interventions: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyatt, A.; Chung, H.; Aston, R.; Gough, K.; Krishnasamy, M. Social Return on Investment economic evaluation of supportive care for lung cancer patients in acute care settings in Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.; Gouldthorpe, C.; Davies, A. Palliative care in the era of novel oncological interventions: Needs some “tweaking”. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 5569–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Hui, D.; Davies, A.; Ripamonti, C.; Capela, A.; DeFeo, G.; Del Fabbro, E.; Bruera, E. MASCC antiemetics in advanced cancer updated guideline. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 8097–8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razvi, Y.; Chan, S.; McFarlane, T.; McKenzie, E.; Zaki, P.; DeAngelis, C.; Pidduck, W.; Bushehri, A.; Chow, E.; Jerzak, K.J. ASCO, NCCN, MASCC/ESMO: A comparison of antiemetic guidelines for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in adult patients. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadul, N.; Elsayem, A.; Palmer, J.L.; Del Fabbro, E.; Swint, K.; Li, Z.; Poulter, V.; Bruera, E. Supportive versus palliative care: What’s in a name?: A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009, 115, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, S.; Palla, S.; Hui, D.; Nguyen, L.; Chacko, R.; Li, Z.; Fadul, N.; Scott, C.; Thornton, V.; Coldman, B.; et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 2011, 16, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organisation. Palliative Care: Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Herrstedt, J.; Roila, F.; Warr, D.; Celio, L.; Navari, R.M.; Hesketh, P.J.; Chan, A.; Aapro, M.S. 2016 Updated MASCC/ESMO Consensus Recommendations: Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting Following High Emetic Risk Chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2017, 25, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, V.; Jensen, S.B.; Smith, D.K.; Bohlke, K.; Bauman, J.; Brennan, M.T.; Coppes, R.P.; Jessen, N.; Malhotra, N.K.; Murphy, B.; et al. Salivary gland hypofunction and/or xerostomia induced by nonsurgical cancer therapies: ISOO/MASCC/ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2825–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.F.; Merlin, J.S. Approaches to opioid prescribing in cancer survivors: Lessons learned from the general literature. Cancer 2022, 128, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.P.; Mehta, Z. Opioids and chronic pain: Where is the balance? Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 18, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, C.; Kosty, M.; Jezdic, S.; Pyle, D.; Berardi, R.; Bergh, J.; El-Saghir, N.; Lotz, J.P.; Österlund, P.; Pavlidis, N.; et al. ESMO/ASCO Recommendations for a Global Curriculum in Medical Oncology Edition 2016. ESMO Open 2016, 1, e000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Terminology | Definition |

|---|---|

| Supportive care | “The prevention and management of the adverse effects of cancer and its treatment. This includes management of physical and psychological symptoms and side effects across the continuum of the cancer journey from diagnosis through treatment to post-treatment care. Supportive care aims to improve the quality of rehabilitation, secondary cancer prevention, survivorship, and end-of-life care” [6]. |

| Palliative care | “The active holistic care of individuals across all ages with serious health-related suffering due to severe illness and especially of those near the end of life. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients, their families and their caregivers” [13] (p. 761). |

| Early palliative care | “Palliative care treatments applied early in the course of a life-threatening disease…In cases of advanced cancer, early palliative care is provided alongside active disease treatment such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy” [11] (p. 7). |

| Timely palliative care | “Early palliative care personalised around patients’ needs and delivered at the optimal time and setting” [14] (p. 3). |

| Best supportive care | No agreed definition, although consensus guidelines are available for best supportive care in clinical trials in advanced cancer [9]. |

| Enhanced supportive care | An initiative by NHS England, which was “developed through recognition of what specialist palliative care can offer, but also from recognition of the barriers to achieving earlier involvement of palliative care expertise within the cancer treatment continuum” [10] (p. 4). (Enhanced supportive care is synonymous with early palliative care). |

| Supportive oncology | “Those aspects of medical care concerned with the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual issues faced by persons with cancer, their families, their communities, and their health-care providers. In this context, supportive oncology describes both those interventions used to support patients who experience adverse effects caused by antineoplastic therapies and those interventions now considered under the broad rubric of palliative care” [15] (p. xii). (Supportive oncology is synonymous with supportive care). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scotté, F.; Taylor, A.; Davies, A. Supportive Care: The “Keystone” of Modern Oncology Practice. Cancers 2023, 15, 3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153860

Scotté F, Taylor A, Davies A. Supportive Care: The “Keystone” of Modern Oncology Practice. Cancers. 2023; 15(15):3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153860

Chicago/Turabian StyleScotté, Florian, Amy Taylor, and Andrew Davies. 2023. "Supportive Care: The “Keystone” of Modern Oncology Practice" Cancers 15, no. 15: 3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153860

APA StyleScotté, F., Taylor, A., & Davies, A. (2023). Supportive Care: The “Keystone” of Modern Oncology Practice. Cancers, 15(15), 3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153860