Frequency and Predictors of Dysplasia in Pseudopolyp-like Colorectal Lesions in Patients with Long-Standing Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

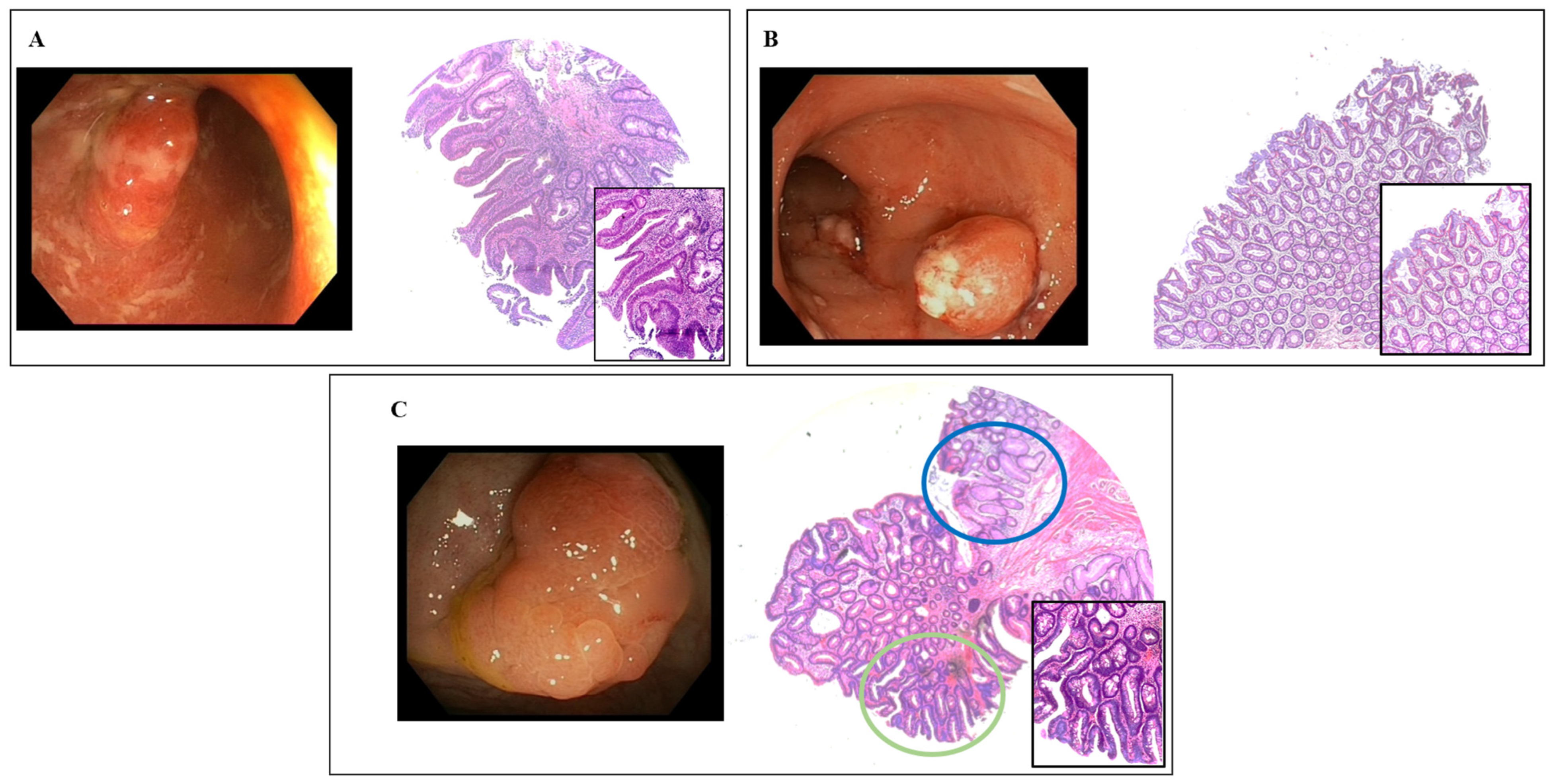

3.2. Endoscopic Characteristics

3.3. Frequency of Dysplasia

3.4. Clinical and Endoscopic Factors Associated with Dysplasia

3.5. Predictive Factors of Dysplasia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jess, T.; Rungoe, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: A Meta-analysis of Population-Based Cohort Studies. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutgens, M.W.M.D.; van Oijen, M.G.H.; van der Heijden, G.J.M.G.; Vleggaar, F.P.; Siersema, P.D.; Oldenburg, B. Declining risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: An updated meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteleone, G.; Pallone, F.; Stolfi, C. The dual role of inflammation in colon carcinogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 11071–11084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairns, S.R.; Scholefield, J.H.; Steele, R.J.; Dunlop, M.G.; Thomas, H.J.W.; Evans, G.D.; Eaden, J.A.; Rutter, M.D.; Atkin, W.P.; Saunders, B.P.; et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut 2010, 59, 666–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annese, V.; Daperno, M.; Rutter, M.D.; Amiot, A.; Bossuyt, P.; East, J.; Ferrante, M.; Götz, M.; Katsanos, K.H.; Kießlich, R.; et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2013, 7, 982–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gionchetti, P.; Dignass, A.; Danese, S.; Dias, F.J.M.; Rogler, G.; Lakatos, P.L.; Adamina, M.; Ardizzone, S.; Buskens, C.J.; Sebastian, S.; et al. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016: Part 2: Surgical management and special situations. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2017, 11, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farraye, F.A.; Odze, R.D.; Eaden, J.; Itzkowitz, S.H. AGA Medical Position Statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Colorectal Neoplasia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- From, A.; Unit, G.; Hospital, G.; Epidemiology, C.; Cancer, B. Cancer morbidity in ulcerative colitis. Gut 1982, 23, 490–497. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M.; Saunders, B.; Wilkinson, K.; Rumbles, S.; Schofield, G.; Kamm, M.; Williams, C.; Price, A.; Talbot, I.; Forbes, A. Severity of Inflammation Is a Risk Factor for Colorectal Neoplasia in Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayos, F.S.; Loftus, E.V.; Jess, T.; Harmsen, W.S.; Bida, J.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Tremaine, W.J.; Sandborn, W.J. Predictive and Protective Factors Associated With Colorectal Cancer in Ulcerative Colitis: A Case-Control Study. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, J.E.; Looman, C.W.N.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Beukers, R.; Tan, A.C.I.T.L.; Weusten, B.L.A.M.; Kuipers, E.J.; Van Der Woude, C.J. The risk of inflammatory bowel disease-related colorectal carcinoma is limited: Results from a nationwide nested case-control study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M.D.; Saunders, B.P.; Wilkinson, K.H.; Rumbles, S.; Schofield, G.; Kamm, M.A.; Williams, C.B.; Price, A.B.; Talbot, I.C.; Forbes, A. Cancer surveillance in longstandinq ulcerative colitis: Endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut 2004, 53, 1813–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.H.R.; Ignjatovic-Wilson, A.; Askari, A.; Lee, G.H.; Warusavitarne, J.; Moorghen, M.; Thomas-Gibson, S.; Saunders, B.P.; Rutter, M.D.; Graham, T.A.; et al. Low-grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis: Risk factors for developing high-grade dysplasia or colorectal cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Dombal, F.T.; Watts, J.M.K.; Watkinson, G.; Goligher, J.C. Local Complications of Ulcerative Colitis: Stricture, Pseudopolyposis, and Carcinoma of Colon and Rectum. Br. Med. J. 1966, 1, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.G.; Chen, X.J.; Huang, J.N.; Chen, J.G.; Lv, M.Y.; Huang, T.Z.; Lan, P.; He, X.S. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease patients with post-inflammatory polyps: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2022, 14, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klarskov, L.; Mogensen, A.M.; Jespersen, N.; Ingeholm, P.; Holck, S. Filiform serrated adenomatous polyposis arising in a diverted rectum of an inflammatory bowel disease patient. Apmis 2011, 119, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, C.E.; Haggitt, R.C.; Burmer, G.C.; Brentnall, T.A.; Stevens, A.C.; Levine, D.S.; Dean, P.J.; Kimmey, M.; Perera, D.R.; Rabinovitch, P.S. DNA aneuploidy in colonic biopsies predicts future development of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1992, 103, 1611–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyse, J.; Lamoureux, E.; Gordon, P.H.; Bitton, A. Occult dysplasia in a localized giant pseudopolyp in Crohn’s colitis: A case report. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 23, 477–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, S.; Rubio, C.A.; Teixeira, C.R.; Kashida, H.; Kogure, E. Pit pattern in colorectal neoplasia: Endoscopic magnifying view. Endoscopy 2001, 33, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satsangi, J.; Silverberg, M.S.; Vermeire, S.; Colombel, J.F. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 2006, 55, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.F.; Bradshaw, J.M. Methods and Devices Reviews of Books The Diabetic Pregnancy ‘SimpLe’ index. Lancet 1980, 8, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.J.; Calderwood, A.H.; Doros, G.; Fix, O.K.; Jacobson, B.C. The Boston bowel preparation scale: A valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2009, 69 (Suppl. S3), 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, D.S.; Katsanos, K.H.; Tsianos, E.V.; Christodoulou, D.K. Pseudopolyps in inflammatory bowel diseases: Have we learned enough? World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, R.; Shah, S.C.; Torres, J.; Castaneda, D.; Glass, J.; Elman, J.; Kumar, A.; Axelrad, J.; Harpaz, N.; Ullman, T.; et al. Association Between Indefinite Dysplasia and Advanced Neoplasia in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Undergoing Surveillance. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 1518–1527.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.H.R.; Al Bakir, I.; Ding, N.S.J.; Lee, G.H.; Askari, A.; Warusavitarne, J.; Moorghen, M.; Humphries, A.; Ignjatovic-Wilson, A.; Thomas-Gibson, S.; et al. Cumulative burden of inflammation predicts colorectal neoplasia risk in ulcerative colitis: A large single-centre study. Gut 2019, 68, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, S.; Oka, S.; Tanaka, S.; Sagami, S.; Hayashi, R.; Ueno, Y.; Arihiro, K.; Chayama, K. Clinical usefulness of narrow band imaging magnifying colonoscopy for assessing ulcerative colitis-associated cancer/dysplasia. Endosc. Int. Open 2016, 4, E1183–E1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lolli, E.; De Cristofaro, E.; Marafini, I.; Troncone, E.; Neri, B.; Zorzi, F.; Biancone, L.; Calabrese, E.; Monteleone, G. Endoscopic Predictors of Neoplastic Lesions in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Patients Undergoing Chromoendoscopy. Cancers 2022, 14, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Iacucci, M.; Ghosh, S.; Ferraz, J.G.P.; Lee, S. Revisiting the distinct histomorphologic features of inflammatory bowel disease–associated neoplastic precursor lesions in the SCENIC and post–DALM. Hum. Pathol. 2020, 100, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.; Smale, S. PTU-125 Positive calprotectin but negative investigations-what next? Gut 2012, 61, A236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballal, S.; Maisterra, S.; López-Serrano, A.; Gimeno-García, A.Z.; Vera, M.I.; Marín-Garbriel, J.C.; DÍaz-Tasende, J.; Márquez, L.; Álvarez, M.A.; Hernández, L.; et al. Real-life chromoendoscopy for neoplasia detection and characterisation in long-standing IBD. Gut 2018, 67, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of Patients | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| median (range) | 54 (26–88) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 70 (67) |

| Disease duration | |

| Median (range) | 192 (90–504) |

| Age at disease onset | |

| Median (range) | 35 (12–67) |

| UC, n (%) | 80 (76) |

| E2 | 52 (65) |

| E3 | 28 (35) |

| CD, n (%) | 25 (24) |

| L2 | 19 (76) |

| L3 | 6 (24) |

| IBD-U, n (%) | 0 |

| Family history of CRC, n (%) | 17 (16) |

| Concomitant PSC, n (%) | 0 |

| Previous therapy with IMMs or biologics, n (%) | 65 (62) |

| Ongoing therapy with ISS or biologics, n (%) | 78 (74) |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | |

| Yes | 11 (10.5) |

| No | 40 (3) |

| Former | 54 (51.5) |

| Previous dysplasia, n (%) | |

| Yes | 6 (6%) |

| Clinical activity | |

| Partial mayo score | |

| Median (range) | 2 (0–9) |

| Harvey–Bradshaw Index | |

| Median (range) | 3 (2–7) |

| Endoscopic activity | |

| Mayo UC score, (n) | |

| 0, n (%) | 33 (31) |

| 1, n (%) | 8 (8) |

| 2, n (%) | 17 (16) |

| 3, n (%) | 22 (21) |

| SES-CD, (n) | |

| Median, range | 7 (1–28) |

| BBPS | |

| Median, range | 8 (3–9) |

| Type of endoscopy, n (%) | |

| Chromoendoscopy (virtual or dye) | 54 (51) |

| White light | 51 (49) |

| Dysplasia n = 23 | No Dysplasia n = 82 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical details | |||

| Age-years | |||

| Median (range) | 60 (26–80) | 50 (30–80) | 0.004 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 17 (74) | 53 (65) | 0.46 |

| IBD type, n (%) | |||

| Ulcerative Colitis | 18 (78) | 62 (76) | 0.79 |

| Crohn’s Disease | 5 (22) | 20 (24) | |

| Family history of colorectal cancer, n (%) | 6 (26) | 11(13) | 0.35 |

| Disease duration—months | |||

| Median (range) | 180 (95–384) | 198 (90–504) | 0.81 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | |||

| yes | 3 (13) | 8 (9) | 0.79 |

| Previous dysplasia, n (%) | 4 (17) | 2 (2) | 0.02 |

| Previous ISS/biologics | 12 (52) | 66 (80) | 0.015 |

| Endoscopic Details | |||

| Inflammation score, median (range) | |||

| Mayo UC score | |||

| - Remission/mild activity (0–1) | 10 (44) | 31 (38) | 0.79 |

| - Moderate/severe activity (2–3) | 8 (35) | 31 (38) | |

| SES-CD | |||

| - Remission/mild activity (<7) | 4 (17) | 10 (12) | 0.34 |

| - Moderate/severe activity (≥7) | 1 (4) | 10 (12) | |

| Procedures with adequate bowel preparation (BBPS ≥ 6), n (%) | 16 (70) | 52 (63) | 0.63 |

| Type of endoscopy | |||

| Chromoendoscopy (virtual or dye) | 10 (43) | 44 (54) | 0.48 |

| White light | 13 (57) | 38 (46) | |

| Dysplasia n = 23 | No Dysplasia n = 82 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | |||

| - Right colon vs. other segments | 10 (43) | 8 (10) | 0.0006 |

| - Transverse colon vs. other segments | 2 (9) | 8 (10) | 0.1 |

| - Left colon vs. other segments | 8 (35) | 44 (53) | 0.004 |

| - Rectum vs. other segments | 3 (13) | 22 (27) | 0.26 |

| Size mm, median (range) | 10 (3–15) | 5 (3–13) | <0.0001 |

| Surface ulceration, n (%) | 9 (39) | 24 (29) | 0.44 |

| Number, n (%) | |||

| Solitary | 9 (39) | 12 (15) | 0.04 |

| Multiple | 14 (61) | 70 (85) | |

| Inflamed surrounding mucosa, n (%) | 11 (48) | 36 (44) | 0.81 |

| Risk Factors | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age, years | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) | 0.007 | 1.1 (1.02 to 1.12) | 0.012 |

| IBD type: ulcerative colitis vs. Crohn disease | 0.82 (0.27 to 2.48) | 0.72 | ||

| Disease duration | 0.98 (0.99 to 1.01) | 0.65 | ||

| Previous dysplasia | 8.52 (1.45 to 50.02) | 0.014 | 9.01 (0.77 to 10.5.2) | 0.07 |

| Previous ISS/biologics | 0.28 (0.11 to 0.75) | 0.011 | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.52) | 0.005 |

| Moderate/severe endoscopic activity | 0.55 (0.21 to 1.42) | 0.22 | ||

| Use of chromoendoscopy | 0.67 (0.26 to 1.72) | 0.41 | ||

| Lesion’s size | 1.23 (1.1 to 1.4) | 0.0008 | 1.39 (1.15 to 1.68) | 0.0005 |

| Lesion location | ||||

| - Cecum/right colon | 8.35 (2.7 to 25.9) | 0.0002 | 5.32 (1.01 to 26.9) | 0.04 |

| - Transverse colon | 1.03 (0.19 to 5.3) | 0.96 | ||

| - Left colon/sigmoid colon | 0.2 (0.06 to 0.65) | 0.003 | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.54) | 0.0008 |

| - Rectum | 1.38 (0.49 to 3.82) | 0.54 | ||

| Presence of inflamed mucosa around the lesion | 1.19 (0.47 to 3.02) | 0.7 | ||

| Ulcerated surface | 1.58 (0.6 to 4.14) | 0.35 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Cristofaro, E.; Lolli, E.; Migliozzi, S.; Sincovih, S.; Marafini, I.; Zorzi, F.; Troncone, E.; Neri, B.; Biancone, L.; Del Vecchio Blanco, G.; et al. Frequency and Predictors of Dysplasia in Pseudopolyp-like Colorectal Lesions in Patients with Long-Standing Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cancers 2023, 15, 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15133361

De Cristofaro E, Lolli E, Migliozzi S, Sincovih S, Marafini I, Zorzi F, Troncone E, Neri B, Biancone L, Del Vecchio Blanco G, et al. Frequency and Predictors of Dysplasia in Pseudopolyp-like Colorectal Lesions in Patients with Long-Standing Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cancers. 2023; 15(13):3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15133361

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Cristofaro, Elena, Elisabetta Lolli, Stefano Migliozzi, Stella Sincovih, Irene Marafini, Francesca Zorzi, Edoardo Troncone, Benedetto Neri, Livia Biancone, Giovanna Del Vecchio Blanco, and et al. 2023. "Frequency and Predictors of Dysplasia in Pseudopolyp-like Colorectal Lesions in Patients with Long-Standing Inflammatory Bowel Disease" Cancers 15, no. 13: 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15133361

APA StyleDe Cristofaro, E., Lolli, E., Migliozzi, S., Sincovih, S., Marafini, I., Zorzi, F., Troncone, E., Neri, B., Biancone, L., Del Vecchio Blanco, G., Calabrese, E., & Monteleone, G. (2023). Frequency and Predictors of Dysplasia in Pseudopolyp-like Colorectal Lesions in Patients with Long-Standing Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cancers, 15(13), 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15133361