Simple Summary

There is a drive to detect cancers at an early stage to improve survival. While this initiative has been associated with better outcomes for certain cancers, testing also leads to patient anxiety and distress. Most of the research in this domain was conducted in asymptomatic patients who attend as part of population-based testing (screening). The literature in individuals with symptoms or with abnormal preliminary results (diagnostics) remains deficient. We conducted a literature search to identify which cancers were underrepresented, what risk factors could contribute to worse psychological outcomes in both screening and diagnostics, and whether any interventions could help to mitigate these. Our search revealed that young, unemployed individuals were at high risk and should therefore be targeted for support. Among the interventions considered, the use of patient leaflets, one-stop clinics, and patient navigators to facilitate patient attendance at their appointments appeared to be the most beneficial.

Abstract

(1) Background: Several studies have described the psychological harms of testing for cancer. However, most were conducted in asymptomatic subjects and in cancers with a well-established screening programme. We sought to establish cancers in which the literature is deficient, and identify variables associated with psychological morbidity and interventions to mitigate their effect. (2) Methods: Electronic bibliographic databases were searched up to December 2020. We included quantitative studies reporting on variables associated with psychological morbidity associated with cancer testing and primary studies describing interventions to mitigate these. (3) Results: Twenty-six studies described individual, testing-related, and organisational variables. Thirteen randomised controlled trials on interventions were included, and these were categorised into five groups, namely the use of information aids, music therapy, the use of real-time videos, patient navigators and one-stop clinics, and pharmacological or homeopathic therapies. (4) Conclusions: The contribution of some factors to anxiety in cancer testing and their specificity of effect remains inconclusive and warrants further research in homogenous populations and testing contexts. Targeting young, unemployed patients with low levels of educational attainment may offer a means to mitigate anxiety. A limited body of research suggests that one-stop clinics and patient navigators may be beneficial in patients attending for diagnostic cancer testing.

1. Introduction

Medical tests to detect cancer are key to improving early diagnosis and improving oncological outcomes, including patient survival. The Faster Diagnostic Framework was set up by NHS England in the U.K. in 2015 to fast-track patients with a possible diagnosis of cancer [1]. One of the aims of this initiative is to reduce anxiety associated with prolonged waiting times, especially for patients irrespective of their diagnosis. Although testing is commonly viewed as beneficial, testing can cause harm. Harms associated with testing may be direct (for example pain associated with the test application and anxiety) or indirect, for example the harms associated with the downstream consequences of a test result including test errors (false positives and false negatives).

The context of testing (screening or diagnosis) and the place of a test in the clinical pathway (early or late) will determine the nature and importance of downstream indirect consequences. Screening usually refers to routine testing in asymptomatic average risk individuals to evaluate their risk of developing cancer. Diagnostic tests, in contrast, principally refer to testing to determine whether at-risk individuals actually have cancer. Whilst the purpose of screening and diagnostic tests are different, it follows that a screening test may lead to diagnostic testing in individuals who are identified as being at increased risk of developing cancer. For example, a missed cancer diagnosis (false negative, FN) may be afforded greater importance than a false positive (FP) result for an individual undergoing diagnostic testing. However, when tests are applied in low-prevalence populations such as in screening, the consequences of a missed cancer diagnosis (FN) need to be balanced against the consequences of receiving an FP for a larger absolute number of individuals. Research to date has largely concentrated on the therapeutic, financial, psychosocial, and legal implications that occur as a result of cancer-screening programmes [2]. In contrast, the consequences associated with diagnostic testing for cancer have received less attention.

There is compelling evidence that a negative testing experience per se may have a detrimental impact on patient satisfaction and reduce motivation to engage with healthcare services or attend for further testing or treatment. Studies have demonstrated a potential link between the level of psychological distress and the strength of the body’s immune system [3,4].

With various initiatives that will result in an increase in the number of individuals undergoing diagnostic testing for cancer, it is important to understand the potential psychological impacts of testing policy. In addition, determining whether certain individuals are more vulnerable to the adverse psychological effects of testing would allow targeting of interventions to mitigate these.

Existing Research

We sought to identify any systematic review concerned with quantifying the psychological associations of cancer testing and the effectiveness of interventions to mitigate this. A scoping search conducted in December 2020 across systematic reviews evaluating the psychological associations of cancer testing across Ovid MEDLINE and Embase yielded a single quantitative review [5] which examined the levels of anxiety, stress, worry, panic, and fear associated with screening tests for breast, colon, prostate, and lung cancers pre-test, post-test, and post-negative-test results. Only studies conducted in the United States and published between 1946 and October 2016 were included. The authors excluded studies about cancer testing in a diagnostic context and confined their review to examination of the consequences of positive test results.

We therefore undertook a review with the aim of addressing deficiencies in the literature apropos of an up-to-date review without geographical restriction considering the psychological associations of testing for cancer and the potential effects of the entire testing process (pre-, during, and post-) regardless of test result. We also sought to ascertain evidence about interventions that mitigate anxiety in individuals undergoing cancer testing. Through this review, we also aim to highlight which cancers have been the most well-researched to date and thereby identify the types of cancer where a paucity of evidence prevails and where further research is mandated.

We anticipated a paucity of the literature concerned with diagnostic testing as opposed to screening and therefore decided to include both types of test application in our review scope. Whilst we hypothesised that there may be overlap in mechanisms of psychological associations and effectiveness between screening and diagnosis, we acknowledged potential differences by test application by distinguishing these in our synthesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Questions and Inclusion Criteria

Two separate frameworks for question formulation were used: SPIDER [6] for question 1, as this was concerned with a phenomenon that could be evaluated using diverse research approaches, and PICO for question 2, which is concerned with the examination of the effectiveness of interventions.

Question components are illustrated in Box 1.

(1) What are the effects of individual characteristics, characteristics of the testing process, and healthcare organisational factors on the psychological associations of cancer testing?

(2) What interventions are effective at reducing the adverse psychological associations of cancer testing?

Box 1. Inclusion criteria for questions 1 and 2.

Question 1

Sample: Adults.

Phenomenon of interest: Testing for cancer (any type).

Design of studies: Cross-sectional, longitudinal (cohort), and mixed-method studies.

Evaluation: Any measure of psychological burden such as worry, anxiety, fear, distress, depression, and uncertainty measured via tools including but not restricted to STAI, HRQoL, SF-12, SF-36, and HADS.

Research type: Quantitative (cross-sectional, case control, and cohort) and mixed-methods, primary studies, or systematic reviews.

Question 2

Population: Adults undergoing diagnostic testing for any type of cancer.

Intervention: Any intervention(s) to improve psychological burden such as worry, anxiety, fear, distress, depression, and uncertainty measured via tools associated with testing for cancer.

Control: No intervention(s) or alternative intervention(s), including standard care.

Outcome: Any measure of psychological burden such as worry, anxiety, fear, distress, depression, and uncertainty measured via tools incuding but not restricted to STAI, HRQoL, SF-12, SF-36, and HADS.

Study Design: Systematic reviews of RCTS or RCTs.

2.2. Search Strategy

Electronic bibliographic databases were searched using a combination of MESH and free-text terms combined using Boolean operators (and/or). OVID MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched for published articles, and the British Library, Library Hub Discover, Opengrey.eu, the Grey Guide, gov.uk (news and communications), and the National Grey Literature Collection for unpublished literature. Electronic database searches were supplemented with searches of reference lists of included systematic reviews and primary studies. All articles from inception to December 2020 were included. Only articles published in English were included. The search strategy is available as an appendix (File S6). This systematic review was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (Registration number CRD42022321906).

2.3. Study Selection

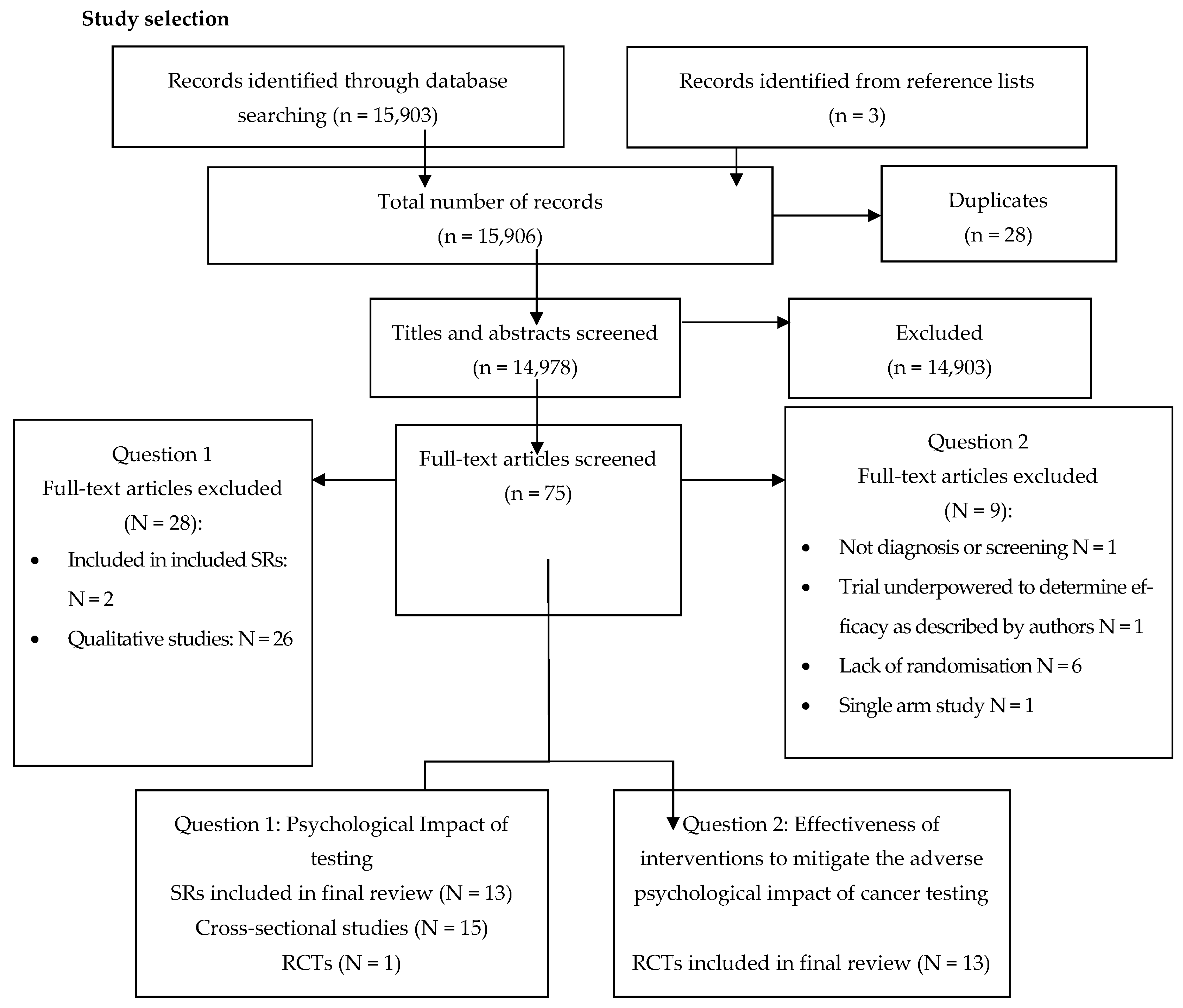

Titles, abstracts, and full texts of potentially relevant titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer against predefined inclusion criteria (Box 1), and reasons for exclusion of studies were documented using a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

For question 1, our plan was to include the results of systematic reviews relevant to our research question and in addition, if the included reviews were of sufficient quality and relevance, to supplement these with studies published since the review literature search completion dates. However, the systematic reviews we identified as relevant to our research questions synthesised a mix of quantitative and qualitative results, and as we were only interested in quantitative research, we were unable to use their synthesised results. We therefore decided to incorporate the quantitative evidence in the reviews by considering the results of primary quantitative studies included in the reviews (if they were not identified from our own searches).

2.4. Data Extraction

A single data extraction form was designed for questions 1 and 2. Data extracted included title, first author, year of publication, study design, aim of study, number of studies/participants, population characteristics, cancer type under investigation, test, intervention (where appropriate), comparator (where appropriate), and results.

2.5. Quality Assessment

For quality assessment of systematic reviews, five criteria drawn from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses were assessed, namely, the inclusion of a clear, focused question, clear question formulation, comprehensive search strategy, quality assessment of studies, and data extraction by two independent reviewers [7].

For cross-sectional studies, a modified JBI Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies [8] was used: the domain (‘was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way’) was not considered relevant to this review question and was omitted. For RCTs, the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool [9] was employed.

We did not identify any cohort or mixed-method studies to include in this review. Quality assessment of primary studies was undertaken in duplicate by FK and CD.

2.6. Data Synthesis

Data synthesis was narrative and supported by tables to map similarities and differences in population, cancer, test type, intervention (where applicable), and outcomes for each of questions 1 and 2. Recognising that psychological associations are likely to be different in screening compared to diagnostic applications of testing, these different testing applications were considered separately for the purposes of synthesis.

On the basis of research identified as part of our scoping review of the predictors of anxiety associated with diagnostic and screening tests [10,11,12], we used three themes as the framework for the synthesis of this review: individual characteristics, testing-related factors, and organisational factors.

3. Results

3.1. Volume of Studies

Question 1: Psychological associations of testing.

A total of 26 studies, including 10 systematic reviews (SRs), 15 cross-sectional studies, and 1 randomised controlled trial (RCT) were identified. Of the 10 SRs, testing was undertaken for screening (7 studies), diagnosis (2 studies), or both (1 study). Nine primary studies were concerned with screening whilst seven were concerned with diagnostic testing.

Question 2: Effectiveness of interventions to mitigate adverse psychological associations of testing.

Thirteen randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included. Interventions were undertaken for screening (five studies) and diagnosis (eight studies).

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies (Files S1 and S2)

Question 1: Psychological associations of testing.

SRs from the following countries were included: U.S.A. (five), Finland (one), Australia (one), Ireland (one), The Netherlands (one), and Canada (one). The total number of studies included in each SR (qualitative and quantitative) ranged from 7 to 59, and the number of subjects ranged from 872 to 199,906. Most SRs focused on single cancers, namely, breast (three), cervical (two), colorectal (two), pancreatic (one), and lung (one), whilst one included various cancers.

Quantitative primary studies from Europe (eight), the U.S.A. (three), Taiwan (one), Australia (one), Oman (one), Canada (one), and Lebanon (one) were included. The number of subjects ranged from 31 to 3671. Studies were concerned with testing for cancer of the cervix (seven), breast (six), prostate (one), and ovary (two). Studies included a variety of tests, and different elements of the testing process including mammography (four), colposcopy (four), notification of abnormal cervical smear results (three), biopsy (two), transvaginal ultrasound scan (two), and HPV testing (one). The severity of psychological outcomes was measured at different time points including before testing (four), on the day of testing (seven), and immediately after testing or after receiving the test results (five). Psychological associations were assessed through various validated tools such as PCQ, STAI, COS-BC, SF-12, HADS, and MBSS, as well as author-designed questionnaires, or a combination of these.

Question 2: Effectiveness of interventions to mitigate adverse psychological associations of testing.

RCTs from the U.S.A. (five), Europe (five), Australia (one), Cameroon (one), and Thailand (one) were included. The number of participants ranged from 16 to 838. Interventions were associated with mammography for breast cancer (two studies), diagnostic or interventional colposcopy for cervical cancer (six studies), colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy for bowel cancer (one study), faecal occult blood test for bowel cancer (one study), a combination of different tests (one study), and biopsies (two studies).

3.3. Quality Assessment

Aside from three reviews [13,14,15] where it was unclear whether the data extraction and quality assessment had been conducted in duplicate, SRs were considered at low risk of bias on the remaining four quality criteria (Table 1).

In the 15 included cross-sectional studies, all clearly defined the inclusion criteria, study subject, and settings, described how the psychological outcomes were measured, and processed the results using appropriate statistical analysis. Of these studies, 12/15 (80%) utilised validated measurement tools, while 3/15 (20%) measured outcomes using open-ended questions concerning the patients’ emotions in addition to quantitative measurements. Only 1/15 (7%) of studies reported on confounders (Table 2).

Table 1.

Quality assessment for systematic reviews for question 1 (adapted from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses).

Table 1.

Quality assessment for systematic reviews for question 1 (adapted from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses).

| Clear, Focused Question | Comprehensive Search Strategy † |

|

| Validated Methods for Data Analysis | Description of Methods Included and Reproducible | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cazacu et al., 2019 [16] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chad-Friedman et al., 2017 [5] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Metsälä et al., 2011 [13] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes to selection NA to two reviewers | Yes | Yes |

| Montgomery et al., 2010 [14] | Yes | Yes | Yes to selection NA to two reviewers | Yes to selection NA to two reviewers | Yes | Yes |

| Nagendiram et al., 2018 [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes to selection NA to two reviewers | Yes | Yes |

| Nelson et al., 2016 [17] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| O’Connor et al., 2016 [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Van der Veld et al., 2017 [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wu et al., 2016 [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Yang et al., 2018 [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

† The authors provided evidence of a logical and reproducible search strategy which identified the PICO components of the question. More than one citation database including grey literature was searched.

Table 2.

Quality assessment for cross-sectional studies for question 2 (using the JBI Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies).

Table 2.

Quality assessment for cross-sectional studies for question 2 (using the JBI Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies).

| Inclusion Criteria Clearly Defined | Study Subjects and Setting Were Clearly Defined | Exposure Measured in Valid and Reliable Way | Measurement of Condition (Were Patients Selected According to Strict Definitions) | Confounders Identified | Strategies to Deal with Confounders Identified | Outcomes Measured in Valid and Reliable Way | Appropriate Statistical Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Alawi et al., 2019 [22] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| April-Sanders et al., 2018 [23] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bekkers et al., 2002 [24] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Bolejko et al., 2015 [25] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Drolet et al., 2011 [26] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| El Hachem et al., 2019 [27] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| French et al., 2006 [28] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gray et al., 2006 [29] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kola et al., 2012 [30] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Liao et al., 2008 [31] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Maissi et al., 2004 [32] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Medd et al., 2005 [33] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| O’Connor et al., 2016 [34] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wiggins et al., 2017 [35] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wiggins et al., 2019 [36] | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

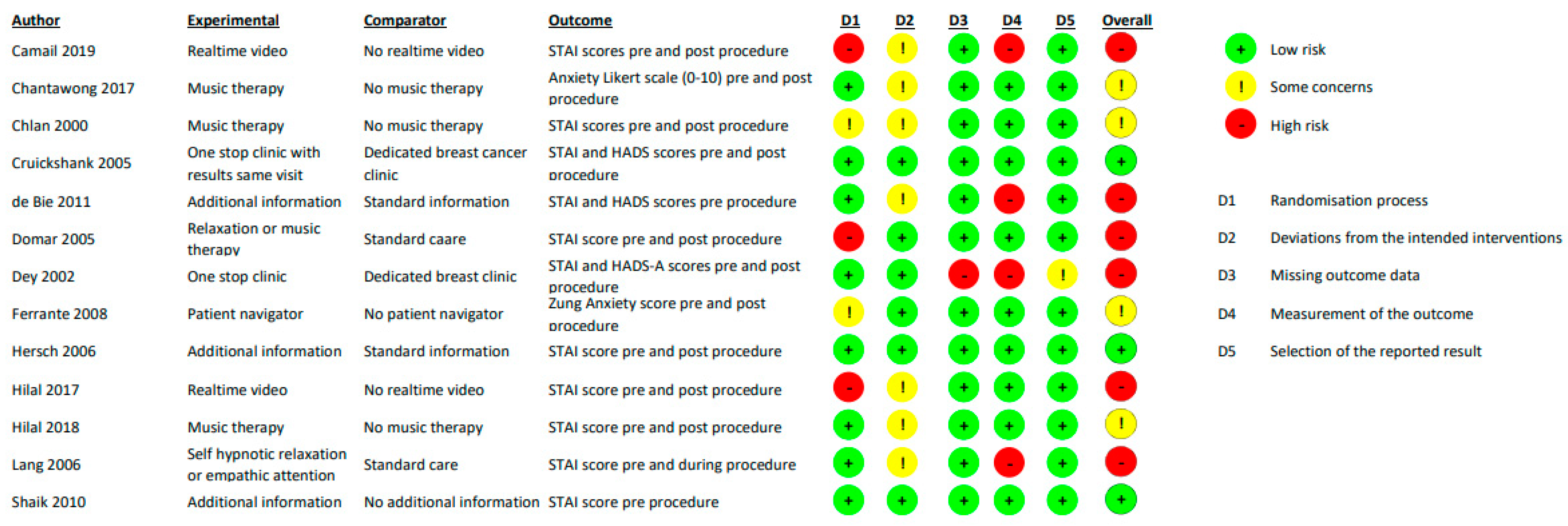

Question 2: Effectiveness of interventions to mitigate adverse psychological associations of testing (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Quality assessment for randomised controlled trials for question 3 (using the Risk of Bias RoB2 tool). Camail 2019 [37]; Chantawong 2017 [38]; Chlan 2000 [39]; Cruickshank 2005 [40]; de Bie 2011 [41]; Domar 2005 [42]; Dey 2002 [43]; Ferrante 2008 [44]; Hersch 2006 [45]; Hilal 2017 [46]; Hilal 2018 [47]; Lang 2006 [48]; Shaik 2010 [49].

A total of 46% (6/13) of the RCTs were at ‘high’ risk of bias, 31% (4/13) at ‘some concerns’, and 23% (3/13) at ‘low’ risk of bias. For those studies regarded as being at high risk of bias, this was attributed to two domains: the randomisation process and the outcome measurement. The studies were graded as ‘low’ or ‘some concerns’ for the risk of bias across the remaining domains because of one or more deviations from the intended intervention, missing outcome data, and selective reporting of results.

3.4. Synthesis of Results

Question 1: Psychological associations of testing.

For synthesis, predictive factors were divided into three categories derived from themes identified in the literature. Included studies investigated the association of the following variables in each of the three predefined categories: psychosocial (age, ethnicity, educational status, personal or family history of cancer, employment status, perceived risk of cancer, presence of partner and children, social support, knowledge of cancer, smoking history, and intrinsic trait anxiety), testing-related factors (cancer site, previous abnormal result or severity of index result, procedure-related anxiety, and previous adverse experience of testing), and organisational factors (satisfaction with information received, waiting times, and communication of results). Psychological outcomes including anxiety, depression, distress, or worry were measured using validated measurement tools such as STAI, HADS, Impact of Events Scale (IES), and General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). Individual reported levels of uncertainty, coping style, and expectations were assessed using various tools including the Psychological Consequences Questionnaire (PCQ), Consequences of Screening–Breast Cancer (COS-BC), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), Multi-Dimensional Health Locus of Control Scale (MHLCS), Miller Behavioral Style Scale (MBSS), and Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale (MUIS) questionnaires. Fear associated with the testing procedure was measured, e.g., pain was measured using visual analogue scales (VAS) or the Fear of Pain Questionnaire-III (FPQ-III). Finally, the consequences of testing on patients’ quality of life were examined using the EuroQol or Short Form-12 tools.

I. Individual (psychosocial) characteristics (Files S3–S5)

1. Age

Screening

Two SRs (including seven studies [16] and seven studies [19] each) and three cross-sectional studies found a negative association between age and psychosocial morbidity in screening for breast [22,23], pancreatic [16], cervical [29], and colorectal [19] cancers.

Four cross-sectional studies found no statistically significant association between age and psychological morbidity with cancer screening for breast [25,27], cervical [26], or ovarian cancers [35].

Two SRs (with 2/15 studies including age as a variable [13] and 5/58 studies including age as a variable [21] in each study) reported conflicting results towards the associations of age on psychological morbidity in breast cancer [13] and colorectal cancer [21] screening.

Diagnosis

Three cross-sectional studies [24,30,34] and one RCT [46] in colposcopy for cervical cancer testing showed no correlation between age and levels of anxiety. One cross-sectional study in breast cancer [31] concluded that age was not a significant predictor for short- or long-term anxiety during the diagnostic phase for women with suspected breast cancer.

One SR including 30 studies [14] reported the role of age as inconclusive.

2. Ethnicity

Screening

One SR [15] on cervical cancer (13 studies), one SR [5] on a combination of cancer types (22 studies), and one cross-sectional study on breast cancer [25] demonstrated that non-white or non-native women were at high risk of psychological distress compared to native or Caucasian women.

In one cross-sectional study on cervical cancer testing [29], ethnicity was not shown to be associated with anxiety following an abnormal cervical smear result.

Diagnostic

One cross-sectional study [34] demonstrated that non-Irish participants were at greater risk of anxiety from cervical cancer testing.

3. Education status

Screening

Three SRs (including 15 studies [13], 13 studies [20], and 58 studies [21] each) and three cross-sectional studies showed a negative association between educational status and anxiety levels in breast [13,25], lung [20], cervical [26], colorectal [21], and ovarian [35] cancer testing. One cross-sectional study [22] found no association between literacy levels and the magnitude of anxiety in women who underwent mammograms for breast cancer screening.

Diagnostic

One SR [21] on the associations of endoscopic procedures for CRC screening showed a negative correlation between education levels and levels of anxiety. Three cross-sectional studies did not find an association between educational level and anxiety in testing for cervical [24,30] and breast cancer [31].

4. Previous experience of cancer

Screening

One SR [20] and two cross-sectional studies described a positive association between a family history of cancer and anxiety associated with testing across lung [20], breast [22], and ovarian [35] cancers.

A single study concerned with the association of previous cancer testing included in the SR by Metsälä [13] did not find an association between a family history of breast cancer and anxiety levels.

Diagnostic

Three studies concerned with the association of previous cancer testing in an SR by Montgomery [14] demonstrated a statistically significant positive correlation between a history of breast cancer and reported levels of distress and anxiety among women awaiting a breast biopsy or curative surgery.

5. Employment

Screening

Two cross-sectional studies demonstrated a negative association between employment status and anxiety levels during breast [22] and cervical [29] cancer screening.

6. Perceived risk of cancer

Screening

One SR [16] in pancreatic cancer and three cross-sectional studies in breast cancer [23,25,32] showed a positive association between a perceived risk of cancer and testing.

Diagnostic

One cross-sectional study [31] demonstrated that a self-perceived probability of breast cancer was associated with statistically higher levels of anxiety before the biopsy but not after a diagnosis of breast cancer.

7. Social support including living with a partner

Screening

Two cross-sectional studies in breast [25] and cervical [26] cancer screening demonstrated a positive association of social support on improved psychological outcomes. One cross-sectional study did not find an association between social support and anxiety levels in women following a false positive ovarian cancer screening result [35].

Diagnostic

Two cross-sectional studies in cervical cancer [24,30] and one in breast cancer [31] demonstrated that having a partner was protective against anxiety with a statistically significantly lower mean state anxiety score.

Montgomery et al. [14], in their SR (30 studies), did not find an association between marital status and psychological distress.

8. Having children

Screening

One cross-sectional study in cervical cancer screening [29] showed that having children was associated with higher levels of anxiety following an abnormal cervical smear test.

Diagnostic

In one cross-sectional study on cervical cancer [30], parous women were at higher risk of colposcopy-associated distress.

One cross-sectional study [24] and one RCT [46] did not find a correlation between having children and its association on anxiety with colposcopy for cervical cancer.

9. Own knowledge of cancer

Screening

Three cross-sectional studies in breast [25] and cervical [26,32] cancers showed that a lack of knowledge about cancer had a positive association with anxiety levels.

10. Smoking status

Screening

One SR [20] in lung cancer (13 studies), one SR [5] across various cancers, and two cross-sectional studies in cervical cancer [26,29] showed a positive association between smoking status and anxiety levels with cancer testing.

Diagnostic

One RCT and one cross-sectional study demonstrated a positive correlation between smoking and colposcopy for cervical cancer [34,46].

11. Trait or intrinsic anxiety and depression

Diagnostic

Five studies included in an SR by Montgomery et al. [14] showed that amongst women referred for colposcopy, those with higher baseline depression scores experienced higher levels of anxiety and depression as well as a greater fear of cancer at the two-year follow-up.

II. Test-related factors

1. Previous experience of testing including severity of initial result

Screening

Two SRs (including 15 studies [13] and 58 studies [21] each) and two cross-sectional studies [26,27] reported a positive association between a previous adverse experience of testing and more severe initial results in breast cancer [13,27], CRC [21], and cervical cancer [26]. One cross-sectional study in cervical cancer [29] did not find an association between the index smear result or number of previous abnormal results and anxiety levels in cervical cancer testing.

Diagnostic

A positive association between a previous negative experience and anxiety levels in cervical cancer testing was demonstrated in one SR [18] (16 studies). Two cross-sectional studies concerned with colposcopy for cervical cancer, however, did not demonstrate an association between previous results and anxiety levels associated with them [24,30].

2. Procedure-related

Intimate and invasive examinations have been significantly and positively associated with higher fear, worry, embarrassment, and worries about potential sequelae across breast, colorectal, lung and cervical cancers [13,15,19,21,34]. Various procedures such as HPV testing, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and prostate needle biopsy were considered in these studies.

III. Organisational

Information about testing

Screening

One cross-sectional study showed that lower satisfaction levels with the information from healthcare professionals in women with a false-positive screening mammography for breast cancer [25] were significantly and positively associated with a greater sense of dejection, anxiety, and poorer sleep. In another cross-sectional study [26] on cervical cancer, women who received their abnormal smear results in person reported higher levels of anxiety than those informed by letter or telephone.

Diagnostic

A cross-sectional study by Bekkers [24] indicated that longer waiting times were statistically positively associated with anxiety in women attending for colposcopy for cervical cancer testing. The authors also concluded that there was a statistically significant association between satisfaction with the information from the GP or gynaecologist and the mean state anxiety scores in those women.

Conclusions for Question 1

Several variables were identified which could have positive correlations with anxiety levels in both screening and diagnostic testing for cancer, namely, being non-white or non-native, a perceived higher risk of developing a malignancy, lack of social support, a positive smoking history, and low educational attainments. In breast and cervical cancers, a lack of knowledge about cancer or the testing process was associated with higher anxiety levels in screening populations only. On the other hand, having a partner was protective in screening and diagnostic testing for cervical cancer. The effect of age was inconsistent even within the same cancer (i.e., some breast cancer studies showed lower age was associated with high anxiety levels, while others showed no difference) for both screening and diagnostic tests.

With regard to testing-related factors, the absence of a previous abnormal test result or the receipt of a severe initial screening result were associated with worse psychological outcomes in screening but not diagnostic testing for cervical and breast cancers. Intimate or invasive modalities such as biopsy, colposcopy, or flexible sigmoidoscopy were associated with high anxiety levels during screening and diagnostic testing. A previous adverse experience of testing was associated with worse anxiety levels in breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer testing.

Finally, some organisational practices could be associated with higher anxiety levels: women who received their results in person and those who experienced longer waiting times for a colposcopy following abnormal smears reported higher anxiety levels. A lack of information about testing and subsequent lack of satisfaction also contributed to greater psychological morbidity.

Question 2. What interventions are effective at reducing the adverse psychological effects of cancer testing? (Table 3)

Table 3.

Results of RCTS: interventions to reduce psychological morbidity associated with cancer testing for question 2.

A total of 13 RCTs concerned with three cancers (breast, cervical, colorectal) were identified. The studies included screening (five studies) and diagnostic testing (eight studies). Interventions were assigned to five categories: use of information aids, music therapy, livestreaming of real-time videos during colposcopy, organisational factors (patient navigators, one-stop clinics), and pharmaceutical and homeopathic therapies. Psychological outcomes including anxiety, distress, depression, and worry were measured using validated tools such as the STAI, HADS, and IES questionnaires, author-designed questionnaires, or a combination of these. These outcomes were assessed at a single time point (at referral, before, during, or after receiving the intervention) or at two or more time points.

1. Use of information aids

Screening

One RCT in breast cancer testing reported on the effectiveness of information aids in the form of DVDs or printed materials. Hersch [45] demonstrated a significant reduction in anxiety levels for women undergoing mammography with a significant reduction in breast cancer worry in the intervention arm.

Diagnosis

One RCT [49] showed a statistically significant reduction in STAI scores with the use of an education pamphlet for women undergoing colonoscopy, while de Bie [41] did not find a clinically or statistically significant improvement in STAI scores in women attending for colposcopy.

2. Music therapy

Diagnosis

Four RCTs were identified associated with cervical (two), breast (one), and colorectal (one) testing.

Chlan [39] demonstrated that music therapy was associated with a significant decrease in STAI scores in those attending for a flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Three RCTs [38,42,47] did not demonstrate a significant effect of music therapy on anxiety levels in women undergoing cervical biopsies, colposcopy, or mammography, respectively.

3. Real-time videos during colposcopy

Diagnosis

The two RCTs [37,46] which assessed the effectiveness of real-time videos in women attending for visualisation of the cervix following an abnormal smear result both failed to show a significant difference in STAI scores between both arms both before and after the procedure.

4. Organisational

Diagnosis

One RCT reporting on interventions during breast cancer testing [44] concluded that the presence of a patient navigator and an immediate communication of results may be helpful in lowering patient anxiety. One RCT [43] showed that one-stop clinics whereby women attending for breast cancer testing underwent investigations and received their results on the same day compared to women seen in the usual pathway was only beneficial in the short term (24 h) but not at follow-up after three weeks or three months.

5. Pharmacological and homeopathic therapies

Diagnosis

One RCT assessing homeopathy in women undergoing breast biopsies [48] noted a significant decline in anxiety with hypnosis and relaxation techniques following this intervention. Cruickshank [40], on the other hand, did not find any significant change in the HADS scores with the self-administration of an inhaled general anaesthetic (isoflurane) in women attending for colposcopy.

Conclusions for Question 2

Most RCTs were conducted in diagnostic populations for breast and cervical cancer. Of the five intervention categories, the use of information aids and organisational modifications such as the introduction of a patient navigator or one-stop clinics appeared to reduce anxiety. Homeopathic and complimentary therapies such as hypnosis may also be helpful. On the other hand, there was minimal evidence to support the use of music therapy or livestreaming of real-time videos during colposcopy. Overall, there is a paucity of evidence to support the majority of the interventions under consideration in this review for any cancer type or testing process.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

Some individual variables such as a real or perceived lack of knowledge of cancer testing, current or previous smoking history in lung and cervical cancer testing, and higher levels of trait anxiety as well as the invasive or intimate nature of some testing modalities (colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, prostate needle biopsy, and colposcopy) have consistently been demonstrated to be associated with higher levels of fear, worry, embarrassment, and anxiety across various cancers (breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, and cervical cancers).

Our review suggested that cultural factors, language, and religious beliefs in women from non-white and immigrant communities may hinder attendance for cervical and breast cancer testing. However, the relevance of ethnicity as a risk factor for higher anxiety remains debatable in view of the variation in cancer types, testing modalities, study designs, and paucity of details with respect to the country of origin, refugee status, or ethnicity for non-native women. Similarly, the role of education remains unclear as the definitions used to report on different levels of education were non-uniform across the included studies. The relevance of age as a risk factor for anxiety was assessed in four SRs and 12 primary studies involving 3444 subjects. Its effect was unclear even within the same cancer. For instance, some BC studies showed that lower age was associated with high anxiety, while others showed no difference. This could be attributed to the heterogeneity in the age thresholds used to triage the subjects into ‘younger’ and ‘older’ categories across the included studies.

For interventions to mitigate the psychological associations of testing, our study appeared to confirm the effectiveness of informational aids which already constitute an integral part of patient care in a clinical setting across the U.K. Other, relatively novel organisational factors such as patient navigators or one-stop clinics seemed to play a role in mitigating anxiety levels. The evidence to support music therapy or real-time videos, which are an integral aspect of the majority of colposcopy clinics across the U.K., was less robust.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of Review Methods

To our knowledge, this is the first review which addresses the harms of cancer testing and evaluates the effectiveness of interventions to mitigate their associations. We conducted a comprehensive literature search and undertook quality assessment in duplicate. We acknowledge a limitation of our review methods is that screening, inclusion, and data extraction were conducted by a single author.

All the included SRs concerned with the psychological association of testing were narrative, and none of these offered a quantitative assessment of the results; it was therefore not appropriate to perform a meta-analysis. In addition, heterogeneity of cancer type, test, and interventions precluded meta-analysis. Heterogeneity of results even within similar populations and testing modalities may be explained by differences in outcome measurement. The outcome ‘psychological distress’ was used broadly and was often used interchangeably with anxiety, depression, stress, and distress across studies. The lack of a universal definition has resulted in the use of a broad spectrum of validated measurement tools including author-designed questionnaires. Finally, study quality was variable and a main limitation across the included primary studies in question was the non-identification of confounders, which undermines the validity of analyses.

The divergence in results across studies could thus be attributed to the lack of consistency pertaining to the heterogeneity across cancer types, measurement tools, definition of psychological distress, and time points at which psychological distress was assessed across studies.

With regard to question 2, most of the randomised controlled trials were conducted in patients attending for diagnostic rather than screening tests and therefore address the mismatch in the existing body of the literature, which is more well-researched in the context of screening tests. However, the interventions to mitigate anxiety were primarily conducted for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancers, that is, cancers with an established screening programme in the U.K. The latter were overrepresented compared to cancers with a lower incidence but which are often lethal, such as ovarian, pancreatic, and lung cancers. Further research into methods to address individuals at risk of, or with symptoms suggestive of, these more lethal cancers would undoubtedly be more helpful to increase attendance for investigations, improve uptake of testing, and may perhaps improve survival through earlier diagnosis.

Finally, the most recent primary studies identified for both questions 1 and 2 were conducted in 2019. We acknowledge that the evidence is likely to have progressed since the completion of this review, thereby impacting on its currency.

4.3. Clinical Implications

The psychological benefit of cancer testing, namely, the reassurance afforded by an estimation of the patient’s risk value for cancer following testing, has been described in the literature [50]. In addition to this, the mortality benefits of population-based screening for breast, lung, colorectal, and cervical cancers have been previously demonstrated [51,52,53,54]. Although screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic average-risk women does not confer any survival benefit, further studies are underway to explore whether diagnostic testing of women who present to their doctors with suspicious symptoms could be associated with a survival benefit. To this end, there is an urgent need to investigate the psychological associations of cancer testing. Existing research is focused on screening for a select number of cancers such as cervical, breast, and colorectal. However, certain fatal and deadly cancers such as ovarian and pancreatic cancers are underrepresented in the existing research portfolio. Evidence from our study suggests that the roles of some individual characteristics (age, ethnicity, educational attainments, employment status, and marital status) warrant further research to understand whether they are modifiers of the psychological associations of cancer testing. Assessment of the applicability of findings is further limited in view of the different screening and testing pathways employed in different countries. In terms of research methods, this area of research poses difficulties. For instance, it is difficult to blind participants and their assessors to interventions to mitigate anxiety in these testing contexts, especially if these involve non-concealable methods such as music therapy or real-time videos. Bias introduced by evaluation of outcome questionnaires may possibly be addressed to improve blinding of outcome measurement.

The result of our literature review suggests that some individual variables such as a real or perceived lack of knowledge of cancer testing, risk behaviours, higher levels of trait anxiety, and the invasive or intimate nature of some testing modalities have consistently been demonstrated to be associated with higher levels of fear, worry, embarrassment, and anxiety. These variables associated with testing encounters could be targeted for any interventions to mitigate the adverse psychological outcomes associated with cancer testing.

Our research demonstrates that modifiable (organisational) factors such as one-stop clinics and patient navigators for intervention evaluation may be beneficial in patients attending for cancer testing. With regard to interventions to mitigate anxiety, shifting towards one-stop clinics represents a potential route to expedite diagnosis and may thereby be helpful to reduce the anxiety associated with prolonged waiting times. Continued use of information aids to educate patients about the cancer under review and the nature of and potential outcomes from associated investigations should be encouraged.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this literature search has identified some potential variables which may be associated with psychological morbidity in both screening and diagnostic cancer testing applications. Targeting certain patient groups and testing situations may offer a means to mitigate anxiety. Certain interventions may be helpful to mitigate the psychological morbidity associated with testing. A limited body of research suggests that one-stop clinics and patient navigators may be beneficial in patients attending for cancer testing. The contribution of some factors to anxiety in cancer testing and their specificity of effect are inconclusive and warrant further research in homogenous populations and testing contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers15133335/s1. File S1. Study characteristics for question 1; File S2. Study characteristics for question 2; File S3. Cross-sectional study results: variables associated with psychological morbidity; File S4. Illustration of results for question 1 (individual characteristics); File S5. Illustration of results for question 1 (testing-related and organisational factors); and File S6. Search strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., C.D. and F.L.K.; methodology, C.D. and F.L.K.; formal analysis, C.D. and F.L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L.K.; writing—review and editing, C.D. and S.S.; visualization, F.L.K.; supervision, S.S. and C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- NHS England. Faster Diagnosis Framework and the Faster Diagnostic Standard. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/faster-diagnosis/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Petticrew, M.P.; Sowden, A.J.; Lister-Sharp, D.; Wright, K. False-negative results in screening programmes: Systematic review of impact and implications. Health Technol. Assess. 2000, 4, 1–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, N.; Iwamitsu, Y.; Kuranami, M.; Okazaki, S.; Nakatani, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Watanabe, M.; Miyaoka, H. Predictors of psychological distress after diagnosis in breast cancer patients and patients with benign breast problems. Psychosomatics 2011, 52, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witek-Janusek, L.; Gabram, S.; Mathews, H.L. Psychologic stress, reduced NK cell activity, and cytokine dysregulation in women experiencing diagnostic breast biopsy. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007, 32, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chad-Friedman, E.; Coleman, S.; Traeger, L.N.; Pirl, W.F.; Goldman, R.; Atlas, S.J.; Park, E.R. Psychological distress associated with cancer screening: A systematic review. Cancer 2017, 123, 3882–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools. Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools. Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Methods. Risk of Bias 2 Cochrane Review Group Starter Pack; Cochrane Methods: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chorley, A.J.; Marlow, L.A.; Forster, A.S.; Haddrell, J.B.; Waller, J. Experiences of cervical screening and barriers to participation in the context of an organised programme: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.J.; Wong, G.; Craig, J.C.; Hanson, C.S.; Ju, A.; Howard, K.; Usherwood, T.; Lau, H.; Tong, A. Men’s perspectives of prostate cancer screening: A systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrison, R.S.; Sheik-Mohamud, D.; McBride, E.; Whitaker, K.L.; Rees, C.; Duffy, S.; von Wagner, C. Patient barriers and facilitators of colonoscopy use: A rapid systematic review and thematic synthesis of the qualitative literature. Prev. Med. 2021, 145, 106413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metsälä, E.; Pajukari, A.; Aro, A.R. Breast cancer worry in further examination of mammography screening—A systematic review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2012, 26, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.; McCrone, S.H. Psychological distress associated with the diagnostic phase for suspected breast cancer: Systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2372–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendiram, A.; Bougher, H.; Banks, J.; Hall, L.; Heal, C. Australian women’s self-perceived barriers to participation in cervical cancer screening: A systematic review. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 31, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazacu, I.M.; Luzuriaga Chavez, A.A.; Saftoiu, A.; Bhutani, M.S. Psychological impact of pancreatic cancer screening by EUS or magnetic resonance imaging in high-risk individuals: A systematic review. Endosc. Ultrasound 2019, 8, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, H.D.; Pappas, M.; Cantor, A.; Griffin, J.; Daeges, M.; Humphrey, L. Harms of Breast Cancer Screening: Systematic Review to Update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2016, 164, 256–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.; Gallagher, P.; Waller, J.; Martin, C.M.; O’Leary, J.J.; Sharp, L.; Irish Cervical Screening Research Consortium (CERVIVA). Adverse psychological outcomes following colposcopy and related procedures: A systematic review. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 123, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velde, J.L.; Blanker, M.H.; Stegmann, M.E.; de Bock, G.H.; Berger, M.Y.; Berendsen, A.J. A systematic review of the psychological impact of false-positive colorectal cancer screening: What is the role of the general practitioner? Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.X.; Raz, D.J.; Brown, L.; Sun, V. Psychological Burden Associated With Lung Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review. Clin. Lung Cancer 2016, 17, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Sriranjan, V.; Abou-Setta, A.M.; Poluha, W.; Walker, J.R.; Singh, H. Anxiety Associated with Colonoscopy and Flexible Sigmoidoscopy: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 1810–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alawi, N.M.; Al-Balushi, N.; Al Salmani, A.A. The Psychological Impact of Referral for Mammography Screening for Breast Cancer among Women in Muscat Governorate: A cross-sectional study. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2019, 19, e225–e229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- April-Sanders, A.; Oskar, S.; Shelton, R.C.; Schmitt, K.M.; Desperito, E.; Protacio, A.; Tehranifar, P. Predictors of Breast Cancer Worry in a Hispanic and Predominantly Immigrant Mammography Screening Population. Womens Health Issues 2017, 27, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkers, R.L.; van der Donck, M.; Klaver, F.M.; van Minnen, A.; Massuger, L.F. Variables influencing anxiety of patients with abnormal cervical smears referred for colposcopy. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2002, 23, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolejko, A.; Hagell, P.; Wann-Hansson, C.; Zackrisson, S. Prevalence, Long-term Development, and Predictors of Psychosocial Consequences of False-Positive Mammography among Women Attending Population-Based Screening. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2015, 24, 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drolet, M.; Brisson, M.; Maunsell, E.; Franco, E.L.; Coutlée, F.; Ferenczy, A.; Fisher, W.; Mansi, J.A. The psychosocial impact of an abnormal cervical smear result. Psychooncology 2012, 21, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hachem, Z.; Zoghbi, M.; Hallit, S. Psychosocial consequences of false-positive results in screening mammography. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care. 2019, 8, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D.P.; Maissi, E.; Marteau, T.M. The psychological costs of inadequate cervical smear test results: Three-month follow-up. Psychooncology 2006, 15, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, N.M.; Sharp, L.; Cotton, S.C.; Masson, L.F.; Little, J.; Walker, L.G.; Avis, M.; Philips, Z.; Russell, I.; Whynes, D.; et al. Psychological effects of a low-grade abnormal cervical smear test result: Anxiety and associated factors. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 94, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kola, S.; Walsh, J.C. Determinants of pre-procedural state anxiety and negative affect in first-time colposcopy patients: Implications for intervention. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2012, 21, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, M.N.; Chen, M.F.; Chen, S.C.; Chen, P.L. Uncertainty and anxiety during the diagnostic period for women with suspected breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2008, 31, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maissi, E.; Marteau, T.M.; Hankins, M.; Moss, S.; Legood, R.; Gray, A. Psychological impact of human papillomavirus testing in women with borderline or mildly dyskaryotic cervical smear test results: Cross sectional questionnaire study. BMJ 2004, 328, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medd, J.C.; Stockler, M.R.; Collins, R.; Lalak, A. Measuring men’s opinions of prostate needle biopsy. ANZ J. Surg. 2005, 75, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.; O’Leary, E.; Waller, J.; Gallagher, P.; D’Arcy, T.; Flannelly, G.; Martin, C.M.; McRae, J.; Prendiville, W.; Ruttle, C.; et al. Trends in, and predictors of, anxiety and specific worries following colposcopy: A 12-month longitudinal study. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, A.T.; Pavlik, E.J.; Andrykowski, M.A. Demographic, clinical, dispositional, and social-environmental characteristics associated with psychological response to a false positive ovarian cancer screening test: A longitudinal study. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 41, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiggins, A.T.; Pavlik, E.J.; Andrykowski, M.A. Psychological Response to a False Positive Ovarian Cancer Screening Test Result: Distinct Distress Trajectories and Their Associated Characteristics. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camail, R.; Kenfack, B.; Tran, P.L.; Viviano, M.; Tebeu, P.-M.; Temogne, L.; Akaaboune, M.; Tincho, E.; Mbobda, J.; Catarino, R.; et al. Benefit of Watching a Live Visual Inspection of the Cervix with Acetic Acid and Lugol Iodine on Women’s Anxiety: Randomized Controlled Trial of an Educational Intervention Conducted in a Low-Resource Setting. JMIR Cancer 2019, 5, e9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantawong, N.; Charoenkwan, K. Effects of Music Listening During Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedure on Pain and Anxiety: A Randomized Trial. J. Low Genit. Tract Dis. 2017, 21, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlan, L.; Evans, D.; Greenleaf, M.; Walker, J. Effects of a single music therapy intervention on anxiety, discomfort, satisfaction, and compliance with screening guidelines in outpatients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2000, 23, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruickshank, M.; Anthony, G.; Fitzmaurice, A.; McConnell, D.; Graham, W.; Alexander, D.; Tunstall, M.; Ross, J. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effect of self-administered analgesia on women’s experience of outpatient treatment at colposcopy. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005, 112, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bie, R.P.; Massuger, L.F.; Lenselink, C.H.; Derksen, Y.H.; Prins, J.B.; Bekkers, R.L. The role of individually targeted information to reduce anxiety before colposcopy: A randomised controlled trial. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 118, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domar, A.D.; Eyvazzadeh, A.; Allen, S.; Roman, K.; Wolf, R.; Orav, J.; Albright, N.; Baum, J. Relaxation techniques for reducing pain and anxiety during screening mammography. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2005, 184, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Bundred, N.; Gibbs, A.; Hopwood, P.; Baildam, A.; Boggis, C.; James, M.; Knox, F.; Leidecker, V.; Woodman, C.; et al. Costs and benefits of a one stop clinic compared with a dedicated breast clinic: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002, 324, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, J.M.; Chen, P.H.; Kim, S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety, and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: A randomized controlled trial. J. Urban Health 2008, 85, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersch, J.; Barratt, A.; Jansen, J.; Irwig, L.; McGeechan, K.; Jacklyn, G.; Thornton, H.; Dhillon, H.; Houssami, N.; McCaffery, K. Use of a decision aid including information on overdetection to support informed choice about breast cancer screening: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilal, Z.; Alici, F.; Tempfer, C.B.; Seebacher, V.; Rezniczek, G.A. Video Colposcopy for Reducing Patient Anxiety During Colposcopy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 130, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilal, Z.; Alici, F.; Tempfer, C.B.; Rath, K.; Nar, K.; Rezniczek, G.A. Mozart for Reducing Patient Anxiety During Colposcopy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, E.V.; Berbaum, K.S.; Faintuch, S.; Hatsiopoulou, O.; Halsey, N.; Li, X.; Berbaum, M.L.; Laser, E.; Baum, J. Adjunctive self-hypnotic relaxation for outpatient medical procedures: A prospective randomized trial with women undergoing large core breast biopsy. Pain 2006, 126, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Hussain, S.M.; Rahn, S.; Desilets, D.J. Effect of an educational pamphlet on colon cancer screening: A randomized, prospective trial. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 22, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, S.B.; Volk, R.J.; Cass, A.R.; Gilani, J.; Spann, S.J. Psychological benefits of prostate cancer screening: The role of reassurance. Health Expect. 2002, 5, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S.; Vulkan, D.; Cuckle, H.; Parmar, D.; Sheikh, S.; Smith, R.; Evans, A.; Blyuss, O.; Johns, L.; Ellis, I.; et al. Annual mammographic screening to reduce breast cancer mortality in women from age 40 years: Long-term follow-up of the UK Age RCT. Health Technol. Assess. 2020, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, H.J.; Van Der Aalst, C.M.; De Jong, P.A.; Scholten, E.T.; Nackaerts, K.; Heuvelmans, M.A.; Lammers, J.-W.J.; Weenink, C.; Yousaf-Khan, U.; Horeweg, N.; et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaukat, A.; Mongin, S.J.; Geisser, M.S.; Lederle, F.A.; Bond, J.H.; Mandel, J.S.; Church, T.R. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, R.; Pesola, F.; Castañón, A.; Sasieni, P. Impact of cervical screening on cervical cancer mortality: Estimation using stage-specific results from a nested case-control study. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).