Shifting the Focus of Signaling Abnormalities in Colon Cancer

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Signaling in the Healthy Intestines

1.2. Signaling in Colon Cancer

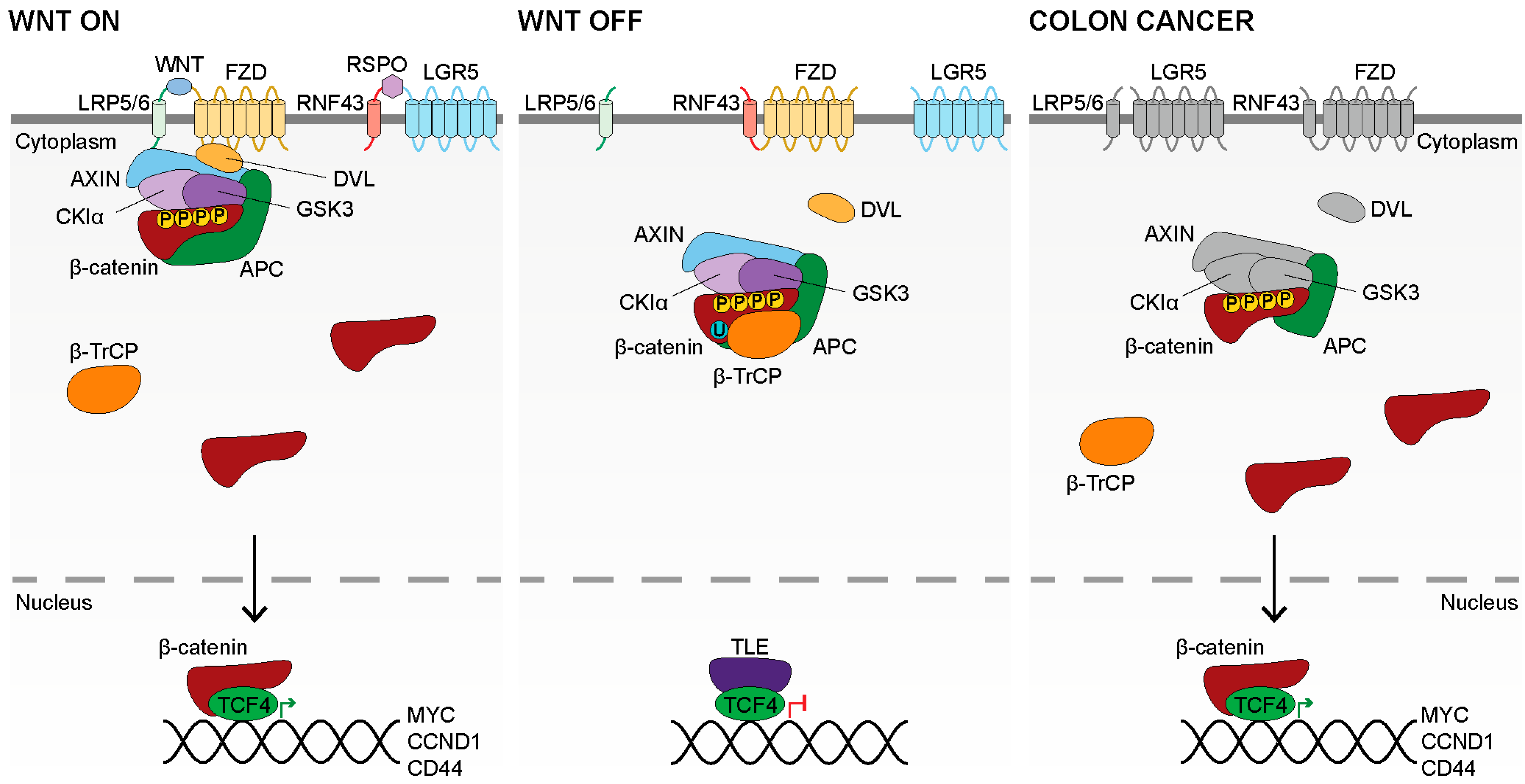

2. WNT Signaling

2.1. WNT Production

2.2. WNT Binding

2.3. WNT Signal Transduction

2.4. Inactive WNT Signaling

2.5. WNT Signaling in Colon Cancer

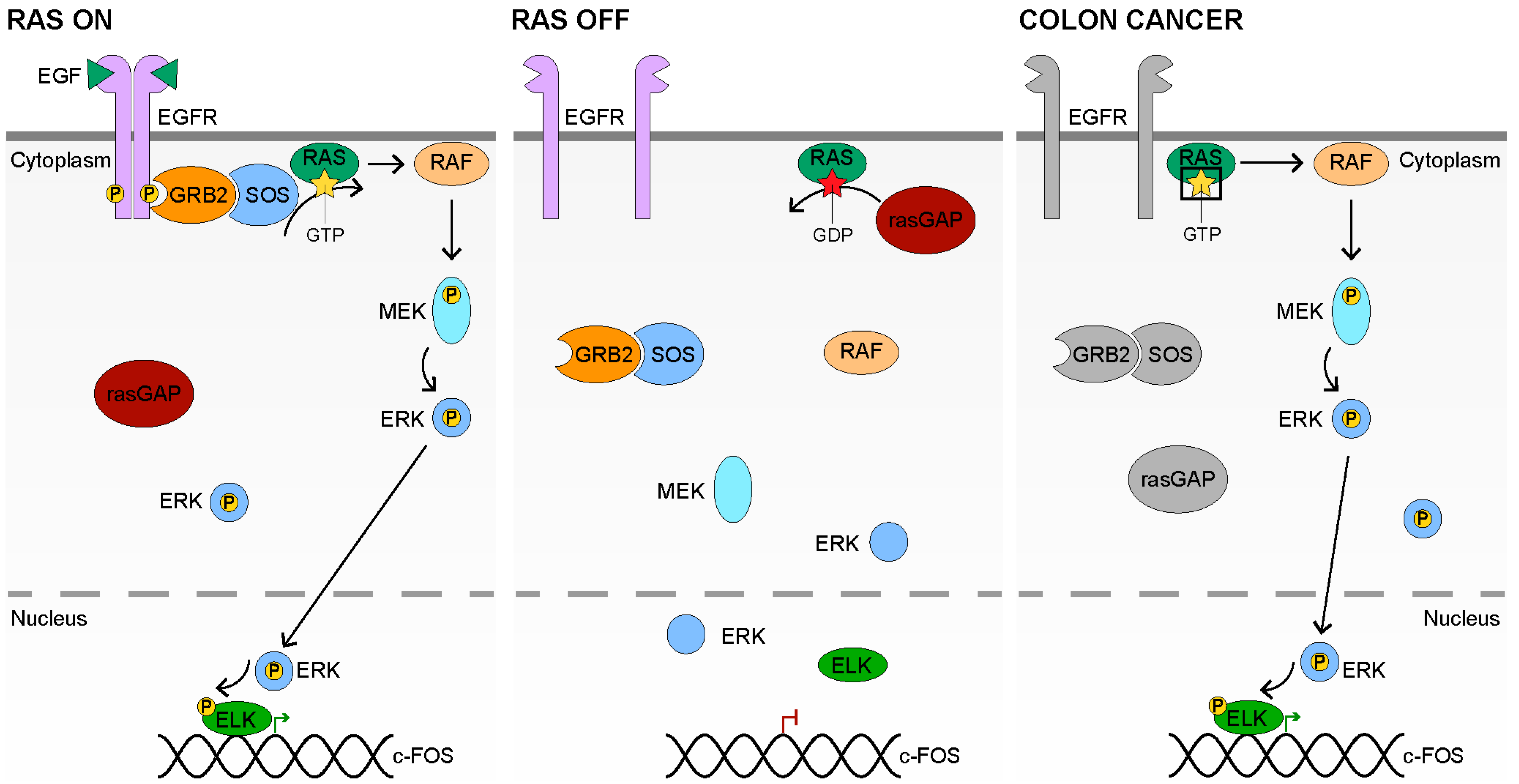

3. RAS Signaling

3.1. RAS Signaling Receptors and Ligands

3.2. RAS Signal Transduction

3.3. Inactive RAS Signaling

3.4. RAS Signaling in Colon Cancer

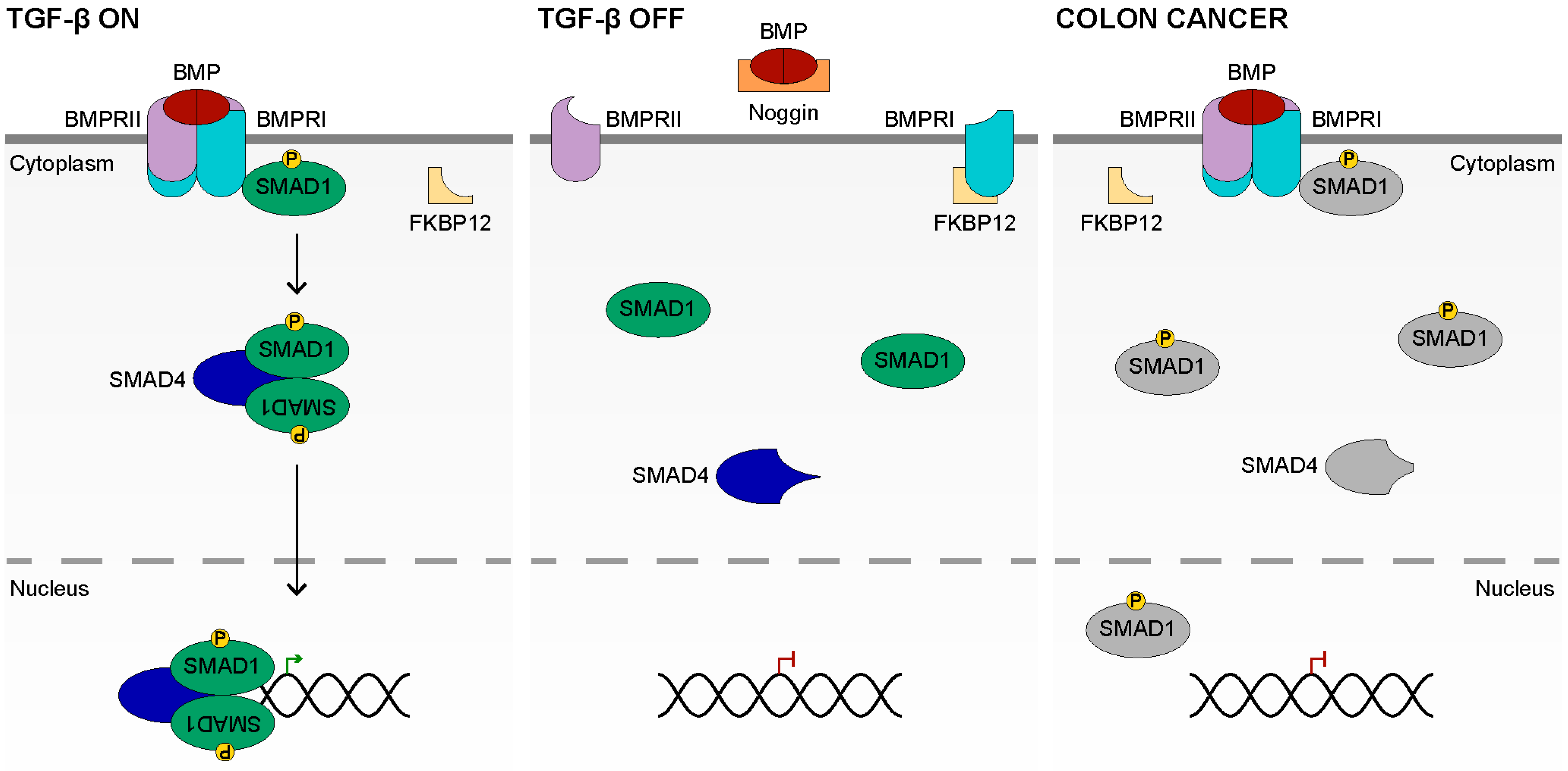

4. TGF-β Signaling

4.1. TGF-β Ligands and Receptors

4.2. TGF-β Signal Transduction

4.3. Inactive TGF-β Signaling

4.4. TGF-β Signaling in Colon Cancer

5. The Cell Cycle in Cancer

6. WNT, RAS and TGF-β

7. The Intestinal Microbiota

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gehart, H.; Clevers, H. Tales from the crypt: New insights into intestinal stem cells. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korinek, V.; Barker, N.; Moerer, P.; Van Donselaar, E.; Huls, G.; Peters, P.J.; Clevers, H. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat. Genet. 1998, 19, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Vries, R.G.; Snippert, H.J.; Van De Wetering, M.; Barker, N.; Stange, D.E.; Van Es, J.H.; Abo, A.; Kujala, P.; Peters, P.J.; et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 2009, 459, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Es, J.H.; van Gijn, M.E.; Riccio, O. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature 2005, 435, 959–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haramis, A.-P.G.; Begthel, H.; Born, M.; van Es, J.; Jonkheer, S.; Offerhaus, G.J.A.; Clevers, H. De Novo Crypt Formation and Juvenile Polyposis on BMP Inhibition in Mouse Intestine. Science 2004, 303, 1684–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Van Es, J.H.; Snippert, H.J.; Stange, D.E.; Vries, R.G.; van den Born, M.; Barker, N.; Shroyer, N.F.; Van De Wetering, M.; Clevers, H. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature 2011, 469, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, M.E.; Nusse, Y.; Kalisky, T.; Lee, J.J.; Dalerba, P.; Scheeren, F.; Lobo, N.; Kulkarni, S.; Sim, S.; Qian, D.; et al. Identification of a cKit+ Colonic Crypt Base Secretory Cell That Supports Lgr5+ Stem Cells in Mice. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1195–1205.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, N.; Sachs, N.; Wiebrands, K.; Ellenbroek, S.; Fumagalli, A.; Lyubimova, A.; Begthel, H.; Born, M.V.D.; van Es, J.H.; Karthaus, W.R.; et al. Reg4+ deep crypt secretory cells function as epithelial niche for Lgr5+ stem cells in colon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5399–E5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farin, H.F.; Jordens, I.; Mosa, H.F.F.M.H.; Basak, O.; Korving, J.; Tauriello, D.V.F.; De Punder, K.; Angers, S.; Peters, K.D.P.P.J.; Maurice, M.; et al. Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem-cell niche. Nature 2016, 530, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Biehs, B.; Chiu, C.; Siebel, C.W.; Wu, Y.; Costa, M.; de Sauvage, F.J.; Klein, O.D. Opposing Activities of Notch and Wnt Signaling Regulate Intestinal Stem Cells and Gut Homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.C.; Zhang, J.; Tong, W.G. BMP signaling inhibits intestinal stem cell self-renewal through suppression of Wnt-beta-catenin signaling. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012, 487, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelstein, B.; Fearon, E.R.; Hamilton, S.R.; Kern, S.E.; Preisinger, A.C.; Leppert, M.; Smits, A.M.; Bos, J.L. Genetic Alterations during Colorectal-Tumor Development. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, S.M.; Zilz, N.; Beazer-Barclay, Y.; Bryan, T.M.; Hamilton, S.R.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature 1992, 359, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.J.; Stern, H.S.; Penner, M.; Hay, K.; Mitri, A.; Bapat, B.V.; Gallinger, S. Somatic APC and K-ras codon 12 mutations in aberrant crypt foci from human colons. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 5527–5530. [Google Scholar]

- Matano, M.; Date, S.; Shimokawa, M.; Takano, A.; Fujii, M.; Ohta, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Kanai, T.; Sato, T. Modeling colorectal cancer using CRISPR-Cas9–mediated engineering of human intestinal organoids. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drost, J.; Van Jaarsveld, R.H.; Ponsioen, B.; Zimberlin, C.; Van Boxtel, R.; Buijs, A.; Sachs, N.; Overmeer, R.M.; Offerhaus, G.J.; Begthel, H.; et al. Sequential cancer mutations in cultured human intestinal stem cells. Nature 2015, 521, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusserow, A.; Pang, K.; Sturm, C.; Hrouda, M.; Lentfer, J.; Schmidt, H.; Technau, U.; Von Haeseler, A.; Hobmayer, B.; Martindale, M.Q.; et al. Unexpected complexity of the Wnt gene family in a sea anemone. Nature 2005, 433, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, N.; Van Es, J.H.; Kuipers, J.; Kujala, P.; Van Den Born, M.; Cozijnsen, M.; Haegebarth, A.; Korving, J.; Begthel, H.; Peters, P.J.; et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 2007, 449, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusse, R.; Varmus, H.E. Many tumors induced by the mouse mammary tumor virus contain a provirus integrated in the same region of the host genome. Cell 1982, 31, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusse, R.; Brown, A.; Papkoff, J.; Scambler, P.; Shackleford, G.; McMahon, A.; Moon, R.; Varmus, H. A new nomenclature for int-1 and related genes: The Wnt gene family. Cell 1991, 64, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.R. The Wnts. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, 3001. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, K.; Vainio, S.; Vassileva, G.; McMahon, A.P. Epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney regulated by Wnt-4. Nature 1994, 372, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monkley, S.J.; Delaney, S.J.; Pennisi, D.J.; Christiansen, J.H.; Wainwright, B.J. Targeted disruption of the Wnt2 gene results in placentation defects. Development 1996, 122, 3343–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeya, M.; Lee, S.M.K.; Johnson, J.E.; McMahon, A.P.; Takada, S. Wnt signalling required for expansion of neural crest and CNS progenitors. Nature 1997, 389, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, S.E.; Willert, K.; Salinas, P.C.; Roelink, H.; Nusse, R.; Sussman, D.J.; Barsh, G.S. WNT Signaling in the Control of Hair Growth and Structure. Dev. Biol. 1999, 207, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.P.; Bradley, A.; McMahon, A.P.; Jones, S. A Wnt5a pathway underlies outgrowth of multiple structures in the vertebrate embryo. Development 1999, 126, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heuvel, M.; Harryman-Samos, C.; Klingensmith, J. Mutations in the segment polarity genes wingless and porcupine impair secretion of the wingless protein. EMBO J. 1993, 12, 5293–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadowaki, T.; Wilder, E.; Klingensmith, J.; Zachary, K.; Perrimon, N. The segment polarity gene porcupine encodes a putative multitransmembrane protein involved in Wingless processing. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 3116–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willert, K.; Brown, J.D.; Danenberg, E.; Duncan, A.W.; Weissman, I.L.; Reya, T.; Yates, J.R.; Nusse, R. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature 2003, 423, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios-Esteves, J.; Haugen, B.; Resh, M.D. Identification of Key Residues and Regions Important for Porcupine-mediated Wnt Acylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 17009–17019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biechele, S.; Cox, B.J.; Rossant, J. Porcupine homolog is required for canonical Wnt signaling and gastrulation in mouse embryos. Dev. Biol. 2011, 355, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrott, J.J.; Cash, G.M.; Smith, A.P.; Barrow, J.R.; Murtaugh, L.C. Deletion of mouse Porcn blocks Wnt ligand secretion and reveals an ectodermal etiology of human focal dermal hypoplasia/Goltz syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 12752–12757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, R.; Satomi, Y.; Kurata, T.; Ueno, N.; Norioka, S.; Kondoh, H.; Takao, T.; Takada, S. Monounsaturated Fatty Acid Modification of Wnt Protein: Its Role in Wnt Secretion. Dev. Cell 2006, 11, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bänziger, C.; Soldini, D.; Schütt, C.; Zipperlen, P.; Hausmann, G.; Basler, K. Wntless, a Conserved Membrane Protein Dedicated to the Secretion of Wnt Proteins from Signaling Cells. Cell 2006, 125, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartscherer, K.; Pelte, N.; Ingelfinger, D.; Boutros, M. Secretion of Wnt Ligands Requires Evi, a Conserved Transmembrane Protein. Cell 2006, 125, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.M.; Thombre, S.; Firtina, Z.; Gray, D.; Betts, D.; Roebuck, J.; Spana, E.P.; Selva, E.M. Sprinter: A novel transmembrane protein required for Wg secretion and signaling. Development 2006, 133, 4901–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, G.S.; Yu, J.; Canning, C.A.; Veltri, C.A.; Covey, T.M.; Cheong, J.K.; Utomo, V.; Banerjee, N.; Zhang, Z.H.; Jadulco, R.C.; et al. WLS-dependent secretion of WNT3A requires Ser209 acylation and vacuolar acidification. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 3357–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, P.; Basler, K. Porcupine-mediated lipidation is required for Wnt recognition by Wls. Dev. Biol. 2012, 361, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, R.; Yu, J.; Kim, J.; Ross, D.R.; Parisi, G.; Clarke, O.B.; Virshup, D.M.; Mancia, F. Structural Basis of WLS/Evi-Mediated Wnt Transport and Secretion. Cell 2021, 184, 194–206.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeg, G.; Lin, X.; Khare, N.; Baumgartner, S.; Perrimon, N. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans are critical for the organization of the extracellular distribution of Wingless. Development 2001, 128, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkut, C.; Ataman, B.; Ramachandran, P.; Ashley, J.; Barria, R.; Gherbesi, N.; Budnik, V. Trans-Synaptic Transmission of Vesicular Wnt Signals through Evi/Wntless. Cell 2009, 139, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.C.; Chaudhary, V.; Bartscherer, K.; Boutros, M. Active Wnt proteins are secreted on exosomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandre, C.; Baena-Lopez, A.; Vincent, J.-P. Patterning and growth control by membrane-tethered Wingless. Nature 2014, 505, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanganello, E.; Hagemann, A.; Mattes, B.; Sinner, C.; Meyen, D.; Weber, S.; Schug, A.; Raz, E.; Scholpp, S. Filopodia-based Wnt transport during vertebrate tissue patterning. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanot, P.; Brink, M.; Samos, C.H.; Hsieh, J.-C.; Wang, Y.; Macke, J.P.; Andrew, D.; Nathans, J.; Nusse, R. A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature 1996, 382, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrli, M.; Dougan, S.T.; Caldwell, K.; Okeefe, L.V.; Schwartz, S.; Vaizel-Ohayon, D.; Schejter, E.D.; Tomlinson, A.; DiNardo, S. Arrow encodes an LDL-receptor-related protein essential for Wingless signalling. Nature 2000, 407, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamai, K.; Semenov, M.; Kato, Y.; Spokony, R.; Liu, C.; Katsuyama, Y.; Hess, F.; Saint-Jeannet, J.-P.; He, X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature 2000, 407, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamai, K.; Zeng, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Harada, Y.; Chang, Z.; He, X. A Mechanism for Wnt Coreceptor Activation. Mol. Cell 2004, 13, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, C.Y.; Waghray, D.; Levin, A.M.; Thomas, C.; Garcia, K.C. Structural Basis of Wnt Recognition by Frizzled. Science 2012, 337, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, C.Y.; Dang, L.T.; You, C.; Chang, J.; De Lau, W.; Zhong, Z.A.; Yan, K.S.; Marecic, O.; Siepe, D.; Li, X.; et al. Surrogate Wnt agonists that phenocopy canonical Wnt and β-catenin signalling. Nature 2017, 545, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourhis, E.; Tam, C.; Franke, Y.; Bazan, J.F.; Ernst, J.; Hwang, J.; Costa, M.; Cochran, A.; Hannoush, R.N. Reconstitution of a Frizzled8·Wnt3a·LRP6 Signaling Complex Reveals Multiple Wnt and Dkk1 Binding Sites on LRP6. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 9172–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Ye, X.; Guo, N.; Nathans, J. Frizzled 2 and frizzled 7 function redundantly in convergent extension and closure of the ventricular septum and palate: Evidence for a network of interacting genes. Development 2012, 139, 4383–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, J.; Baljinnyam, B.; Stanger, K.; Sercan, H.O.; Ji, Y.; Andres, O.; Rubin, J.S.; Hannoush, R.N.; Schulte, G. Systematic Mapping of WNT-FZD Protein Interactions Reveals Functional Selectivity by Distinct WNT-FZD Pairs. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 6789–6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakugawa, S.; Langton, P.F.; Zebisch, M.; Howell, S.A.; Chang, T.-H.; Liu, Y.; Feizi, T.; Bineva-Todd, G.; O’Reilly, N.; Snijders, B.; et al. Notum deacylates Wnt proteins to suppress signalling activity. Nature 2015, 519, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusse, R.; Fuerer, C.; Ching, W.; Harnish, K.; Logan, C.; Zeng, A.; ten Berge, D.; Kalani, Y. Wnt Signaling and Stem Cell Control. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2008, 73, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinka, A.; Wu, W.; Delius, H.; Monaghan, A.P.; Blumenstock, C.; Niehrs, C. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature 1998, 391, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyns, L.; Bouwmeester, T.; Kim, S.-H.; Piccolo, S.; De Robertis, E. Frzb-1 Is a Secreted Antagonist of Wnt Signaling Expressed in the Spemann Organizer. Cell 1997, 88, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruciat, C.-M.; Niehrs, C. Secreted and Transmembrane Wnt Inhibitors and Activators. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a015081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.-X.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Charlat, O.; Oster, E.; Avello, M.; Lei, H.; Mickanin, C.; Liu, D.; Ruffner, H.; et al. ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature 2012, 485, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.-K.; Spit, M.; Jordens, I.; Low, T.Y.; Stange, D.; Van De Wetering, M.; Van Es, J.H.; Mohammed, S.; Heck, A.; Maurice, M.; et al. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature 2012, 488, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmonm, K.S.; Gong, X.; Lin, Q. R-spondins function as ligands of the orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5 to regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11452–11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cliffe, A.; Hamada, F.; Bienz, M. A Role of Dishevelled in Relocating Axin to the Plasma Membrane during Wingless Signaling. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilić, J.; Huang, Y.-L.; Davidson, G.; Zimmermann, T.; Cruciat, C.-M.; Bienz, M.; Niehrs, C. Wnt Induces LRP6 Signalosomes and Promotes Dishevelled-Dependent LRP6 Phosphorylation. Science 2007, 316, 1619–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Huang, H.; Tamai, K.; Zhang, X.; Harada, Y.; Yokota, C.; Almeida, K.; Wang, J.; Doble, B.; Woodgett, J.; et al. Initiation of Wnt signaling: Control of Wnt coreceptor Lrp6 phosphorylation/activation via frizzled, dishevelled and axin functions. Development 2008, 135, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.; Wu, W.; Shen, J. Casein kinase 1 gamma couples Wnt receptor activation to cytoplasmic signal transduction. Nature 2005, 438, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Tamai, K.; Doble, B.; Li, S.; Huang, H.; Habas, R.; Okamura, H.; Woodgett, J.; He, X. A dual-kinase mechanism for Wnt co-receptor phosphorylation and activation. Nature 2005, 438, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.; Ng, S.S.; Boersema, P.J.; Low, T.Y.; Karthaus, W.R.; Gerlach, J.; Mohammed, S.; Heck, A.; Maurice, M.; Mahmoudi, T.; et al. Wnt Signaling through Inhibition of β-Catenin Degradation in an Intact Axin1 Complex. Cell 2012, 149, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.-K.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Association of the APC Tumor Suppressor Protein with Catenins. Science 1993, 262, 1734–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, J.; Jerchow, B.-A.; Würtele, M.; Grimm, J.; Asbrand, C.; Wirtz, R.; Kühl, M.; Wedlich, D.; Birchmeier, W. Functional Interaction of an Axin Homolog, Conductin, with β-Catenin, APC, and GSK3β. Science 1998, 280, 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Semenov, M. Control of beta-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell 2002, 108, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, M.; Hatakeyama, S.; Shirane, M. An F-box protein, FWD1, mediates ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of beta-catenin. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 2401–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishida, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Ikeda, S. Axin, a negative regulator of the wnt signaling pathway, directly interacts with adenomatous polyposis coli and regulates the stabilization of beta-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 10823–10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, S.; Kishida, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Murai, H.; Koyama, S.; Kikuchi, A. Axin, a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway, forms a complex with GSK-3beta and beta -catenin and promotes GSK-3beta -dependent phosphorylation of beta -catenin. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 1371–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.; del Viso, F.; Duncan, A.R.; Robson, A.; Hwang, W.; Kulkarni, S.; Liu, K.; Khokha, M.K. RAPGEF5 Regulates Nuclear Translocation of β-Catenin. Dev. Cell 2018, 44, 248–260.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, D.L.; Weis, W.I. Beta-catenin directly displaces Groucho/TLE repressors from Tcf/Lef in Wnt-mediated transcription activation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arce, L.; Pate, K.T.; Waterman, M.L. Groucho binds two conserved regions of LEF-1 for HDAC-dependent repression. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, J.; von Kries, J.P.; Kühl, M. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature 1996, 38, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, M.; van de Wetering, M.; Oosterwegel, M. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 1996, 86, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wetering, M.; Oosterwegel, M.; Dooijes, D. Identification and cloning of TCF-1, a T lymphocyte-specific transcription factor containing a sequence-specific HMG box. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, S.; Izon, D.; Hofhuis, F.; Robanus-Maandag, E.; Riele, H.T.; Van De Watering, M.; Oosterwegel, M.; Wilson, A.; Macdonald, H.R.; Clevers, H. An HMG-box-containing T-cell factor required for thymocyte differentiation. Nature 1995, 374, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.; Rendl, M.; Fuchs, E. Tcf3 Governs Stem Cell Features and Represses Cell Fate Determination in Skin. Cell 2006, 127, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angus-Hill, M.L.; Elbert, K.M.; Hidalgo, J.; Capecchi, M.R. T-cell factor 4 functions as a tumor suppressor whose disruption modulates colon cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4914–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Es, J.H.; Haegebarth, A.; Kujala, P. A critical role for the Wnt effector Tcf4 in adult intestinal homeostatic self-renewal. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 32, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Genderen, C.; Okamura, R.M.; Fariñas, I. Development of several organs that require inductive epithelial-mesenchymal interactions is impaired in LEF-1-deficient mice. Genes. Dev. 1994, 8, 2691–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, R.M.; Sigvardsson, M.; Galceran, J. Redundant regulation of T cell differentiation and TCRalpha gene expression by the transcription factors LEF-1 and TCF-1. Immunity 1998, 8, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterwegel, M.; Van De Wetering, M.; Timmerman, J.; Kruisbeek, A.; Destree, O.; Meijlink, F.; Clevers, H. Differential expression of the HMG box factors TCF-1 and LEF-1 during murine embryogenesis. Development 1993, 118, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Wetering, M.; Castrop, J.; Korinek, V. Extensive alternative splicing and dual promoter usage generate Tcf-1 protein isoforms with differential transcription control properties. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996, 16, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.-C.; Sparks, A.B.; Rago, C.; Hermeking, H.; Zawel, L.; da Costa, L.T.; Morin, P.J.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Identification of c- MYC as a Target of the APC Pathway. Science 1998, 281, 1509–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtutman, M.; Zhurinsky, J.; Simcha, I. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 5522–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Wiesmann, M.; Rohan, M. Elevated expression of axin2 and hnkd mRNA provides evidence that Wnt/beta -catenin signaling is activated in human colon tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14973–14978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munemitsu, S.; Albert, I.; Souza, B.; Rubinfeld, B.; Polakis, P. Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 3046–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosin-Arbesfeld, R.; Townsley, F.; Bienz, M. The APC tumour suppressor has a nuclear export function. Nature 2000, 406, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin-Arbesfeld, R.; Cliffe, A.; Brabletz, T.; Bienz, M. Nuclear export of the APC tumour suppressor controls beta-catenin function in transcription. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 1101–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groden, J.; Thliveris, A.; Samowitz, W.; Carlson, M.; Gelbert, L.; Albertsen, H.; Joslyn, G.; Stevens, J.; Spirio, L.; Robertson, M.; et al. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell 1991, 66, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, E.C.; Murayama, K.; Kato-Murayama, M. Crystal structures of the armadillo repeat domain of adenomatous polyposis coli and its complex with the tyrosine-rich domain of Sam68. Structure 2011, 19, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yost, C.; Torres, M.; Miller, J.R.; Huang, E.; Kimelman, D.; Moon, R.T. The axis-inducing activity, stability, and subcellular distribution of beta-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aberle, H.; Bauer, A.; Stappert, J. β-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 3797–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, R.A.; Cox, R.T.; Moline, M.M.; Roose, J.; Polevoy, G.A.; Clevers, H.; Peifer, M.; Bejsovec, A. Drosophila Tcf and Groucho interact to repress Wingless signalling activity. Nature 1998, 395, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levanon, D.; Goldstein, R.E.; Bernstein, Y.; Tang, H.; Goldenberg, D.; Stifani, S.; Paroush, Z.; Groner, Y. Transcriptional repression by AML1 and LEF-1 is mediated by the TLE/Groucho corepressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 11590–11595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; Johnson, K.A.; Bryan, T.M.; Hill, D.E.; Markowitz, S.; Willson, J.K.; Paraskeva, C.; Petersen, G.M.; Hamilton, S.R.; Vogelstein, B. The APC gene product in normal and tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 2846–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. Lessons from Hereditary Colorectal Cancer. Cell 1996, 87, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, P.J.; Sparks, A.B.; Korinek, V. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science 1997, 275, 1787–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinek, V.; Barker, N.; Morin, P.J. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC-/- colon carcinoma. Science 1997, 275, 1784–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.B.; Smith, K.J.; Beazer-Barclay, Y.; Hamilton, S.R.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Inactivation of both APC alleles in human and mouse tumors. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 5953–5958. [Google Scholar]

- Luongo, C.; Moser, A.R.; Gledhill, S.; Dove, W.F. Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 5947–5952. [Google Scholar]

- Miyaki, M.; Seki, M.; Okamoto, M.; Yamanaka, A.; Maeda, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Kikuchi, R.; Iwama, T.; Ikeuchi, T.; Tonomura, A. Genetic changes and histopathological types in colorectal tumors from patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancer Res. 1990, 50, 7166–7173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyaki, M.; Tanaka, K.; Kikuchi-Yanoshita, R.; Muraoka, M.; Konishi, M. Familial polyposis: Recent advances. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 1995, 19, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson, A.G. Antioncogenes and human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 10914–10921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A.B.; Morin, P.J.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Mutational analysis of the APC/beta-catenin/Tcf pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 1130–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Sansom, O.J.; Meniel, V.S.; Muncan, V.; Phesse, T.J.; Wilkins, J.A.; Reed, K.R.; Vass, J.K.; Athineos, D.; Clevers, H.; Clarke, A.R. Myc deletion rescues Apc deficiency in the small intestine. Nature 2007, 446, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downward, J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat. Cancer 2003, 3, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, J.L. Ras oncogenes in human cancer: A review. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 4682–4689. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Carpenter, G.; King, L. Epidermal growth factor-receptor-protein kinase interactions. Co-purification of receptor and epidermal growth factor-enhanced phosphorylation activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255, 4834–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, A.L.; Stern, D.F.; Vaidyanathan, L.; Decker, S.J.; Drebin, J.A.; Greene, M.I.; Weinberg, R.A. The neu oncogene: An erb-B-related gene encoding a 185,000-Mr tumour antigen. Nature 1984, 312, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.H.; Issing, W.; Miki, T.; Popescu, N.C.; Aaronson, S.A. Isolation and characterization of ERBB3, a third member of the ERBB/epidermal growth factor receptor family: Evidence for overexpression in a subset of human mammary tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 9193–9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plowman, G.D.; Culouscou, J.M.; Whitney, G.S.; Green, J.M.; Carlton, G.W.; Foy, L.; Neubauer, M.G.; Shoyab, M. Ligand-specific activation of HER4/p180erbB4, a fourth member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 1746–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Carpenter, G. Human epidermal growth factor: Isolation and chemical and biological properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Ushiro, H.; Stoscheck, C.; Chinkers, M. A native 170,000 epidermal growth factor receptor-kinase complex from shed plasma membrane vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massagué, J. Transforming growth factor-alpha. A model for membrane-anchored growth factors. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 15, 21393–21396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashiyama, S.; Abraham, J.A.; Miller, J.; Fiddes, J.C.; Klagsbrun, M. A Heparin-Binding Growth Factor Secreted by Macrophage-Like Cells That Is Related to EGF. Science 1991, 251, 936–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R.C.; Chung, E.; Coffey, R.J. EGF receptor ligands. Exp. Cell Res. 2003, 284, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riethmacher, D.; Sonnenberg-Riethmacher, E.; Brinkmann, V.; Yamaai, T.; Lewin, G.R.; Birchmeier, C. Severe neuropathies in mice with targeted mutations in the ErbB3 receptor. Nature 1997, 389, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassmann, M.; Casagranda, F.; Orioli, D.; Simon, H.; Lai, C.; Klein, R.; Lemke, G. Aberrant neural and cardiac development in mice lacking the ErbB4 neuregulin receptor. Nature 1995, 378, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, D.F.; Kamps, M.P. EGF-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of p185neu: A potential model for receptor interactions. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.R.; Borrello, I.; Bellot, F.; Comoglio, P.; Schlessinger, J. Egf binding to its receptor triggers a rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of the erbB-2 protein in the mammary tumor cell line SK-BR-3. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 1647–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarden, Y.; Sliwkowski, M.X. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.; Schlessinger, J. Regulation of signal transduction and signal diversity by receptor oligomerization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1994, 19, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarden, Y.; Schlessinger, J. Epidermal growth factor induces rapid, reversible aggregation of the purified epidermal growth factor receptor. Biochemistry 1987, 26, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarden, Y.; Schlessinger, J. Self-phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor: Evidence for a model of intermolecular allosteric activation. Biochemistry 1987, 26, 1434–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.M.; Berger, M.; Mendrola, J.M.; Cho, H.-S.; Leahy, D.J.; A Lemmon, M. EGF Activates Its Receptor by Removing Interactions that Autoinhibit Ectodomain Dimerization. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.W.; Cho, H.-S.; Eigenbrot, C.; Ferguson, K.M.; Garrett, T.P.J.; Leahy, D.J.; Lemmon, M.A.; Sliwkowski, M.X.; Ward, C.W.; Yokoyama, S. An Open-and-Shut Case? Recent Insights into the Activation of EGF/ErbB Receptors. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, E.; Daly, R.; Batzer, A.; Li, W.; Margolis, B.; Lammers, R.; Ullrich, A.; Skolnik, E.; Bar-Sagi, D.; Schlessinger, J. The SH2 and SH3 domain-containing protein GRB2 links receptor tyrosine kinases to ras signaling. Cell 1992, 70, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buday, L.; Downward, J. Epidermal growth factor regulates p21ras through the formation of a complex of receptor, Grb2 adapter protein, and Sos nucleotide exchange factor. Cell 1993, 73, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.W.; Kaplan, S.; Lowenstein, E.J.; Schlessinger, J.; Bar-Sagi, D. Grb2 mediates the EGF-dependent activation of guanine nucleotide exchange on Ras. Nature 1993, 363, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chardin, P.; Camonis, J.H.; Gale, N.W.; Van Aelst, L.; Schlessinger, J.; Wigler, M.H.; Bar-Sagi, D. Human Sos1: A guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras that binds to GRB2. Science 1993, 260, 1338–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlessinger, J. SH2/SH3 signaling proteins. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1994, 4, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boriack-Sjodin, P.A.; Margarit, S.M.; Bar-Sagi, D.; Kuriyan, J. The structural basis of the activation of Ras by Sos. Nature 1998, 394, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medema, R.H.; de Vries-Smits, A.M.; van der Zon, G.C.; A Maassen, J.; Bos, J.L. Ras activation by insulin and epidermal growth factor through enhanced exchange of guanine nucleotides on p21ras. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993, 13, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Sagi, D. The Sos (Son of sevenless) protein. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 1994, 5, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodie, S.A.; Wolfman, A. The 3Rs of life: Ras, Raf and growth regulation. Trends Genet. 1994, 10, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruder, J.T.; Heidecker, G.; Rapp, U.R. Serum-, TPA-, and Ras-induced expression from Ap-1/Ets-driven promoters requires Raf-1 kinase. Genes Dev. 1992, 6, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brtva, T.R.; Drugan, J.K.; Ghosh, S.; Terrell, R.S.; Campbell-Burk, S.; Bell, R.M.; Der, C.J. Two Distinct Raf Domains Mediate Interaction with Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 9809–9812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, P.; Haser, W.; Haystead, T.A.J.; Vincent, L.A.; Roberts, T.M.; Sturgill, T.W. Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase by v-Raf in NIH 3T3 Cells and in Vitro. Science 1992, 257, 1404–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakis, J.M.; App, H.; Zhang, X.-F.; Banerjee, P.; Brautigan, D.L.; Rapp, U.R.; Avruch, J. Raf-1 activates MAP kinase-kinase. Nature 1992, 358, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, C.M.; Erikson, R.L. Extracellular signals and reversible protein phosphorylation: What to Mek of it all. Cell 1993, 74, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, L.; Leevers, S.J.; Gómez, N.; Nakielny, S.; Cohen, P.; Marshall, C.J. Activation of the MAP kinase pathway by the protein kinase raf. Cell 1992, 71, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, C.M.; Alessandrini, A.; Erikson, R.L. Erks: Their fifteen minutes has arrived. Cell Growth Differ. Mol. Biol. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 1992, 3, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, D.M.; Rossomando, A.J.; Martino, P.; Erickson, A.K.; Her, J.H.; Shabanowitz, J.; Hunt, D.F.; Weber, M.J.; Sturgill, T.W. Identification of the regulatory phosphorylation sites in pp42/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase). EMBO J. 1991, 10, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.H.; Sarnecki, C.; Blenis, J. Nuclear localization and regulation of erk- and rsk-encoded protein kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992, 12, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.F.; Seth, A.; Raden, D.L.; Bowman, D.S.; Fay, F.S.; Davis, R.J. Serum-induced translocation of mitogen-activated protein kinase to the cell surface ruffling membrane and the nucleus. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 122, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karin, M.; Hunter, T. Transcriptional control by protein phosphorylation: Signal transmission from the cell surface to the nucleus. Curr. Biol. 1995, 5, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, T. Signaling-2000 and beyond. Cell 2000, 100, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.; A Gonzalez, F.; Gupta, S.; Raden, D.L.; Davis, R.J. Signal transduction within the nucleus by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 24796–24804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, H.; Kortenjann, M.; Thomae, O.; Moomaw, C.; Slaughter, C.; Cobb, M.H.; E Shaw, P. ERK phosphorylation potentiates Elk-1-mediated ternary complex formation and transactivation. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortenjann, M.; Thomae, O.; E Shaw, P. Inhibition of v-raf-dependent c-fos expression and transformation by a kinase-defective mutant of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Erk2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 4815–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yordy, J.S.; Muise-Helmericks, R.C. Signal transduction and the Ets family of transcription factors. Oncogene 2000, 19, 6503–6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlessinger, J. Ligand-Induced, Receptor-Mediated Dimerization and Activation of EGF Receptor. Cell 2002, 110, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gureasko, J.; Shen, K.; Cole, P.A.; Kuriyan, J. An Allosteric Mechanism for Activation of the Kinase Domain of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. Cell 2006, 125, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jura, N.; Endres, N.F.; Engel, K.; Deindl, S.; Das, R.; Lamers, M.H.; Wemmer, D.E.; Zhang, X.; Kuriyan, J. Mechanism for Activation of the EGF Receptor Catalytic Domain by the Juxtamembrane Segment. Cell 2009, 137, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigler, H.T.; A McKanna, J.; Cohen, S. Rapid stimulation of pinocytosis in human carcinoma cells A-431 by epidermal growth factor. J. Cell Biol. 1979, 83, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguinot, L.; Lyall, R.M.; Willingham, M.C.; Pastan, I. Down-regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in KB cells is due to receptor internalization and subsequent degradation in lysosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 2384–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.; Beardmore, J.; Kanety, H.; Schlessinger, J.; Hopkins, C.R. Localization of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor within the endosome of EGF-stimulated epidermoid carcinoma (A431) cells. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 102, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boguski, M.S.; McCormick, F. Proteins regulating Ras and its relatives. Nature 1993, 366, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trahey, M.; McCormick, F. A cytoplasmic protein stimulates normal N-ras p21 GTPase, but does not affect oncogenic mutants. Science 1987, 238, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G.A.; Yatani, A.; Clark, R.; Conroy, L.; Polakis, P.; Brown, A.M.; McCormick, F. Gap Domains Responsible for Ras P21-Dependent Inhibition of Muscarinic Atrial K + Channel Currents. Science 1992, 255, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.C.; Manandhar, A.; Carrasco, M.A.; Gurbani, D.; Gondi, S.; Westover, K.D. Biochemical and Structural Analysis of Common Cancer-Associated KRAS Mutations. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J.; Neel, B.G.; Ikura, M. NMR-based functional profiling of RASopathies and oncogenic RAS mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4574–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, H.; Bardelli, A.; Lengauer, C.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B.; Velculescu, V.E. Tumorigenesis: RAF/RAS oncogenes and mismatch-repair status. Nature 2002, 418, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minden, A.; Lin, A.; Smeal, T.; Dérijard, B.; Cobb, M.; Davis, R.; Karin, M. c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation correlates with activation of the JNK subgroup but not the ERK subgroup of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 6683–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minden, A.; Lin, A.; McMahon, M.; Lange-Carter, C.; Dérijard, B.; Davis, R.J.; Johnson, G.L.; Karin, M. Differential Activation of ERK and JNK Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases by Raf-1 and MEKK. Science 1994, 266, 1719–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.J. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 2000, 103, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massagué, J. TGFβ signalling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer Genome Landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, H.L.; Roberts, A.B.; Derynck, R. The Discovery and Early Days of TGF-beta: A Historical Perspective. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a021865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derynck, R.; Jarrett, J.A.; Chen, E.Y.; Eaton, D.H.; Bell, J.R.; Assoian, R.K.; Roberts, A.B.; Sporn, M.B.; Goeddel, D.V. Human transforming growth factor-beta complementary DNA sequence and expression in normal and transformed cells. Nature 1985, 316, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentry, E.L.; Lioubin, M.N.; Purchio, A.F.; Marquardt, H. Molecular events in the processing of recombinant type 1 pre-pro-transforming growth factor beta to the mature polypeptide. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988, 8, 4162–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, T.; Sebald, W.; Dreyer, M.K. Crystal structure of the BMP-2–BRIA ectodomain complex. Nat. Genet. 2000, 7, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massagué, J. Receptors for the TGF-beta family. Cell 1992, 69, 1067–7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Lodish, H.F. Receptors for the TGF-beta superfamily: Multiple polypeptides and serine/threonine kinases. Trends Cell Biol. 1993, 3, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, D.M. The TGF-beta superfamily: New members, new receptors, and new genetic tests of function in different organisms. Genes Dev. 1994, 8, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Massagué, J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 2003, 113, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrana, J.L. Signaling by the TGFβ superfamily. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013, 5, a011197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, J.C.; Van Den Brink, G.R.; Bleuming, S.A. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 is expressed by, and acts upon, mature epithelial cells in the colon. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Ventura, F.; Doody, J.; Massagué, J. Human type II receptor for bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs): Extension of the two-kinase receptor model to the BMPs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 3479–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massagué, J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998, 67, 753–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, M.; Liu, F.; Hata, A.; Doody, J.; Massagué, J. The TGF-beta family mediator Smad1 is phosphorylated directly and activated functionally by the BMP receptor kinase. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrana, J.L.; Attisano, L.; Wieser, R. Mechanism of activation of the TGF-beta receptor. Nature 1994, 370, 341–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, R.; Wrana, J.L.; Massagué, J. GS domain mutations that constitutively activate T beta R-I, the downstream signaling component in the TGF-beta receptor complex. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 2199–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huse, M.; Muir, T.W.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.-G.; Kuriyan, J.; Massagué, J. The TGF beta receptor activation process: An inhibitor- to substrate-binding switch. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attisano, L.; Wrana, J.L. Signal transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science 2002, 296, 1646–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías-Silva, M.; Abdollah, S.; Hoodless, P.A. MADR2 is a substrate of the TGFbeta receptor and its phosphorylation is required for nuclear accumulation and signaling. Cell 1996, 87, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Hata, A.; Baker, J.C.; Doody, J.; Cárcamo, J.; Harland, R.M.; Massague, J. A human Mad protein acting as a BMP-regulated transcriptional activator. Nature 1996, 381, 620–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.; We, R. Receptor-associated Mad homologues synergize as effectors of the TGF-beta response. Nature 1996, 383, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagna, G.; Hata, A.; Hemmati-Brivanlou, A. Partnership between DPC4 and SMAD proteins in TGF-beta signalling pathways. Nature 1996, 383, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Pouponnot, C.; Massagué, J. Dual role of the Smad4/DPC4 tumor suppressor in TGFbeta-inducible transcriptional complexes. Genes. Dev. 1997, 11, 3157–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, G.J.; Beach, D. p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGF-beta-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature 1994, 371, 257–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datto, M.B.; Li, Y.; Panus, J.F.; Howe, D.J.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, X.F. Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 5545–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynisdóttir, I.; Polyak, K.; Iavarone, A.; Massagué, J. Kip/Cip and Ink4 Cdk inhibitors cooperate to induce cell cycle arrest in response to TGF-beta. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 1831–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, L.B.; De Jesús-Escobar, J.M.; Harland, R.M. The Spemann Organizer Signal noggin Binds and Inactivates Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4. Cell 1996, 86, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppe, J.; Greenwald, J.; Wiater, E.; Leon, J.M.R.; Economides, A.; Kwiatkowski, W.; Affolter, M.; Vale, W.W.; Belmonte, J.C.I.; Choe, S. Structural basis of BMP signalling inhibition by the cystine knot protein Noggin. Nature 2002, 420, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccolo, S.; Sasai, Y.; Lu, B.; De Robertis, E. Dorsoventral Patterning in Xenopus: Inhibition of Ventral Signals by Direct Binding of Chordin to BMP-4. Cell 1996, 86, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Liu, F.; Massague, J. Mechanism of TGFbeta receptor inhibition by FKBP12. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 3866–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, T.; Takase, M.; Nishihara, A. Smad6 inhibits signalling by the TGF-beta superfamily. Nature 1997, 389, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, A.; Afrakhte, M.; Morén, A. Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature 1997, 389, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacGrogan, D.; Pegram, M.; Slamon, D.; Bookstein, R. Comparative mutational analysis of DPC4 (Smad4) in prostatic and colorectal carcinomas. Oncogene 1997, 15, 1111–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, S.; Wang, J.; Myeroff, L. Inactivation of the type II TGF-beta receptor in colon cancer cells with microsatellite instability. Science 1995, 268, 1336–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R.; Myeroff, L.L.; Liu, B.; Willson, J.K.; Markowitz, S.D.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. Microsatellite instability and mutations of the transforming growth factor beta type II receptor gene in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 5548–5550. [Google Scholar]

- Riggins, G.J.; Thiagalingam, S.; Rozenblum, E.; Weinstein, C.L.; Kern, S.E.; Hamilton, S.R.; Willson, J.K.; Markowitz, S.D.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. Mad-related genes in the human. Nat. Genet. 1996, 13, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Hata, A.; Lo, R.S.; Massague, J.; Pavletich, N.P. A structural basis for mutational inactivation of the tumour suppressor Smad4. Nature 1997, 388, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, A.; Lo, R.S.; Wotton, D.; Lagna, G.; Massague, J. Mutations increasing autoinhibition inactivate tumour suppressors Smad2 and Smad4. Nature 1997, 388, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, E.; Massagué, J. Transforming Growth Factor-β Signaling in Immunity and Cancer. Immunity 2019, 50, 924–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardee, A.B. G 1 Events and Regulation of Cell Proliferation. Science 1989, 246, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagosklonny, M.V.; Pardee, A.B. The Restriction Point of the Cell Cycle. Cell Cycle 2002, 1, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Traganos, F.; Darzynkiewicz, Z. Threshold expression of cyclin E but not D type cyclins characterizes normal and tumour cells entering S phase. Cell Prolif. 1995, 28, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekholm, S.V.; Zickert, P.; Reed, S.I.; Zetterberg, A. Accumulation of Cyclin E Is Not a Prerequisite for Passage through the Restriction Point. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 3256–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhnert, F.; Davis, C.R.; Wang, H.-T.; Chu, P.; Lee, M.; Yuan, J.; Nusse, R.; Kuo, C.J. Essential requirement for Wnt signaling in proliferation of adult small intestine and colon revealed by adenoviral expression of Dickkopf-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, N.; Ridgway, R.A.; Van Es, J.H.; Van De Wetering, M.; Begthel, H.; van den Born, M.; Danenberg, E.; Clarke, A.R.; Sansom, O.J.; Clevers, H. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 2009, 457, 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Luongo, C.; Gould, K.; McNeley, M.; Shoemaker, A.; Dove, W. ApcMin: A mouse model for intestinal and mammary tumorigenesis. Eur. J. Cancer 1995, 31, 1061–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, L.E.; O’Rourke, K.P.; Simon, J.; Tschaharganeh, D.F.; van Es, J.H.; Clevers, H.; Lowe, S.W. Apc Restoration Promotes Cellular Differentiation and Reestablishes Crypt Homeostasis in Colorectal Cancer. Cell 2015, 161, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, O.; Beumer, J.; Wiebrands, K.; Seno, H.; van Oudenaarden, A.; Clevers, H. Induced Quiescence of Lgr5+ Stem Cells in Intestinal Organoids Enables Differentiation of Hormone-Producing Enteroendocrine Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 20, 177–190.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.W.Y.; Stange, D.E.; Page, M.E.; Buczacki, S.; Wabik, A.; Itami, S.; van de Wetering, M.; Poulsom, R.; Wright, N.A.; Trotter, M.W.B.; et al. Lrig1 controls intestinal stem-cell homeostasis by negative regulation of ErbB signalling. Nature 2012, 14, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snippert, H.J.; Schepers, A.G.; Van Es, J.H.; Simons, B.; Clevers, H. Biased competition between Lgr5 intestinal stem cells driven by oncogenic mutation induces clonal expansion. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wetering, M.; Sancho, E.; Verweij, C. The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell 2002, 111, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.; Penn, L.Z. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat. Cancer 2008, 8, 976–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, C.V. MYC on the Path to Cancer. Cell 2012, 149, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, G.F.; Hann, S.R. A role for transcriptional repression of p21CIP1 by c-Myc in overcoming transforming growth factor beta -induced cell-cycle arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 9498–9503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staller, P.; Peukert, K.; Kiermaier, A.; Seoane, J.; Lukas, J.; Karsunky, H.; Möröy, T.; Bartek, J.; Massague, J.; Hänel, F.; et al. Repression of p15INK4b expression by Myc through association with Miz-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-R.; Kang, Y.; Siegel, P.M.; Massagué, J. E2F4/5 and p107 as Smad cofactors linking the TGFbeta receptor to c-myc repression. Cell 2002, 110, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, B.J.; Blain, S.W.; Seoane, J. Myc downregulation by transforming growth factor beta required for activation of the p15(Ink4b) G(1) arrest pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999, 19, 5913–5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nateri, A.S.; Spencer-Dene, B.; Behrens, A. Interaction of phosphorylated c-Jun with TCF4 regulates intestinal cancer development. Nature 2005, 437, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, C.; Johnson, J.; Watanabe, G. Transforming p21ras mutants and c-Ets-2 activate the cyclin D1 promoter through distinguishable regions. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 23589–23597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakiri, L.; Lallemand, D.; Bossy-Wetzel, E.; Yaniv, M. Cell cycle-dependent variations in c-Jun and JunB phosphorylation: A role in the control of cyclin D1 expression. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 2056–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, M.; Kolbus, A.; Piu, F.; Szabowski, A.; Möhle-Steinlein, U.; Tian, J.; Karin, M.; Angel, P.; Wagner, E.F. Control of cell cycle progression by c-Jun is p53 dependent. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaulian, E.; Karin, M. AP-1 in cell proliferation and survival. Oncogene 2001, 20, 2390–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansom, O.J.; Reed, K.R.; van de Wetering, M. Cyclin D1 is not an immediate target of beta-catenin following Apc loss in the intestine. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 28463–28467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, M.; Doody, J.; Massagué, J. Opposing BMP and EGF signalling pathways converge on the TGF-beta family mediator Smad1. Nature 1997, 389, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, M.; Doody, J.; Timokhina, I.; Massague, J. A mechanism of repression of TGFbeta / Smad signaling by oncogenic Ras. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 804–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermeking, H.; Rago, C.; Schuhmacher, M.; Li, Q.; Barrett, J.F.; Obaya-Gonzalez, A.J.; O’Connell, B.C.; Mateyak, M.; Tam, W.; Kohlhuber, F.; et al. Identification of CDK4 as a target of c-MYC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, P.W.; Mittnacht, S.; Dulic, V.; Arnold, A.; Reed, S.I.; Weinberg, R.A. Regulation of retinoblastoma protein functions by ectopic expression of human cyclins. Cell 1992, 70, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbour, J.W.; Dean, D.C. The Rb/E2F pathway: Expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 2393–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.Y.; Ehmann, G.L.; Giangrande, P.H.; Nevins, J.R. A role for Myc in facilitating transcription activation by E2F1. Oncogene 2008, 27, 4172–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtani, K.; DeGregori, J.; Nevins, J.R. Regulation of the cyclin E gene by transcription factor E2F1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 12146–12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartek, J.; Bartkova, J.; Lukas, J. The retinoblastoma protein pathway and the restriction point. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1996, 8, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.S.; Narisawa, T.; Wright, P.; Vukusich, D.; Weisburger, J.H.; Wynder, E.L. Colon carcinogenesis with azoxymethane and dimethylhydrazine in germ-free rats. Cancer Res. 1975, 35, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, K.; Wang, B.; Cao, H. 626–Gut Microbiota from Colorectal Cancer Patients Enhances the Progression of Intestinal Adenoma in Apc Min/+Mice. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Rhee, K.-J.; Albesiano, E.; Rabizadeh, S.; Wu, X.; Yen, H.-R.; Huso, D.L.; Brancati, F.L.; Wick, E.; McAllister, F.; et al. A human colonic commensal promotes colon tumorigenesis via activation of T helper type 17 T cell responses. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, L.B.; Faria, F.B.; da Graça, A.N. Clostridium difficile toxin A attenuates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2014, 82, 2680–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tao, L.; Zhang, J.; Meraner, P.; Tovaglieri, A.; Wu, X.; Gerhard, R.; Zhang, X.; Stallcup, W.B.; Miao, J.; He, X.Z.X.; et al. Frizzled proteins are colonic epithelial receptors for C. difficile toxin B. Nature 2016, 538, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derwa, Y.; Gracie, D.J.; Hamlin, P.J.; Ford, A.C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy of probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, M.A.; Ried, T. Shifting the Focus of Signaling Abnormalities in Colon Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14030784

Brown MA, Ried T. Shifting the Focus of Signaling Abnormalities in Colon Cancer. Cancers. 2022; 14(3):784. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14030784

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Markus A., and Thomas Ried. 2022. "Shifting the Focus of Signaling Abnormalities in Colon Cancer" Cancers 14, no. 3: 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14030784

APA StyleBrown, M. A., & Ried, T. (2022). Shifting the Focus of Signaling Abnormalities in Colon Cancer. Cancers, 14(3), 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14030784