Quantitative Framework for Bench-to-Bedside Cancer Research

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

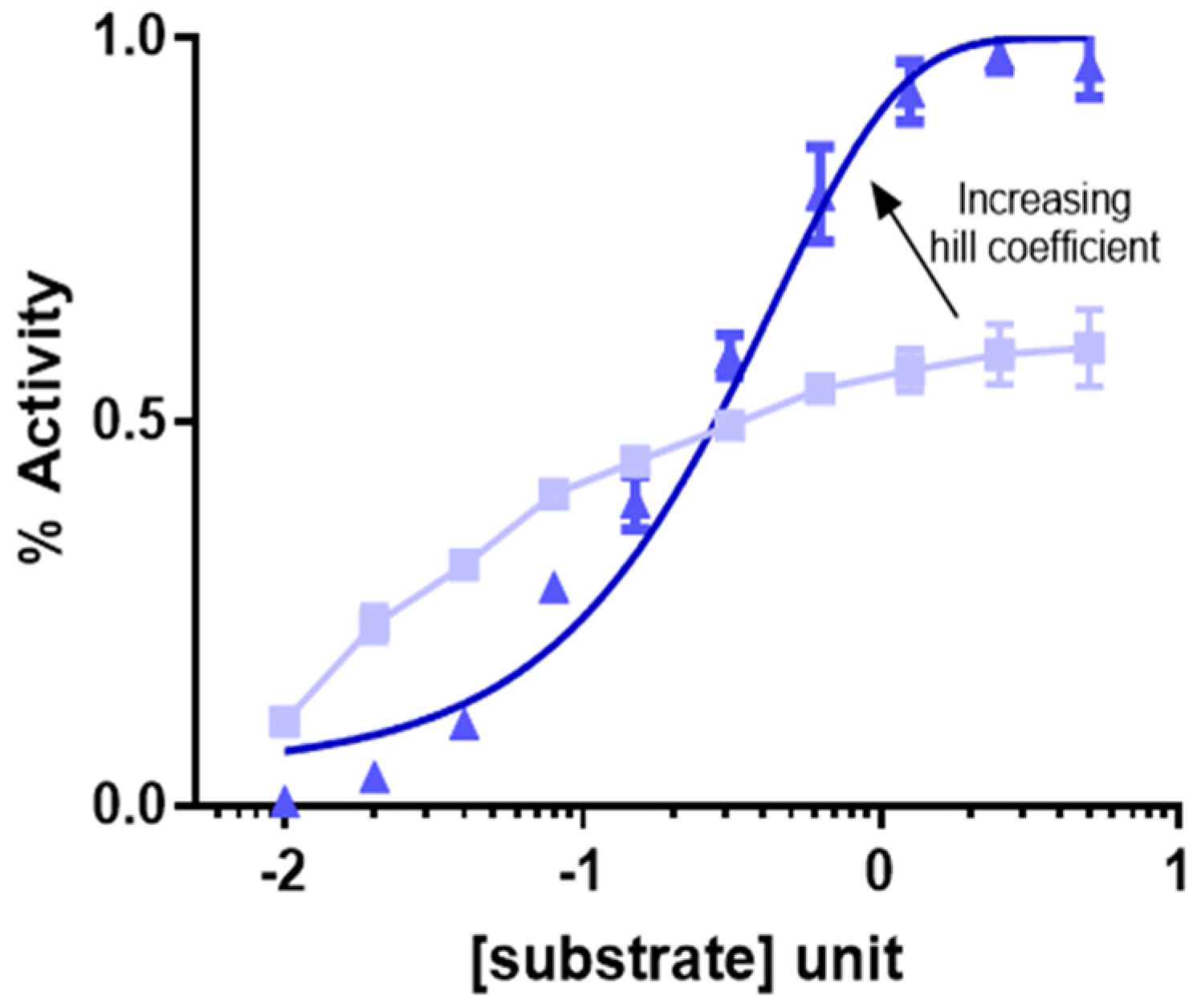

2. Modeling Drug Dose Response

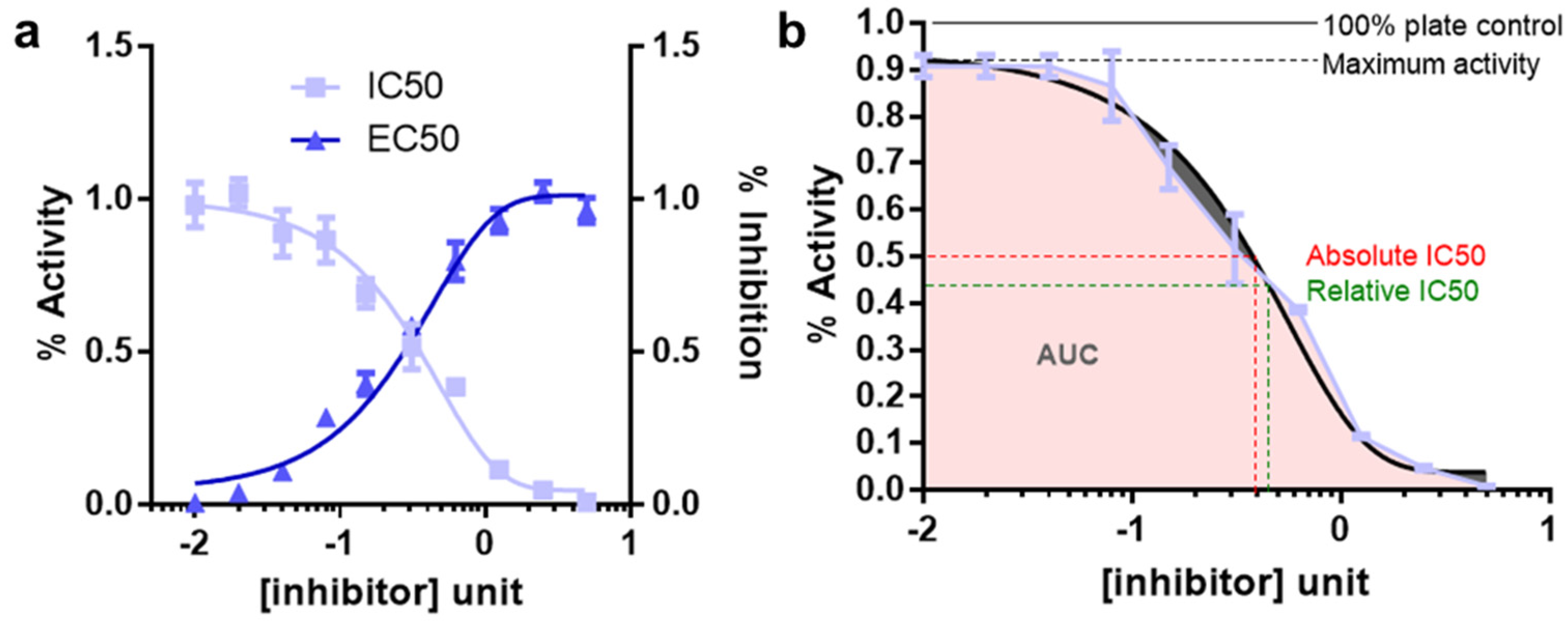

3. Determination of IC50 for Inhibitors

- Well defined top and bottom plateau values need to be established. To do so, it is important to use sufficient range of inhibitor concentrations. These parameters are critical for the mathematical models used to fit the data

- A minimum of 8–10 inhibitor concentration data points for an accurate IC50 determination should be used

- Concentration ranges for the inhibitors should be spaced equally

- The concentration data point counts and the range should be chosen so that half the data points on the IC50 curve are above the IC50 value and half are below the IC50 value. This is difficult for IC50 measurements for compounds for which there exist no prior knowledge. In this case, the inhibitors should be tested for response using a broader range of doses followed by final IC50 estimation using narrower range of doses

- Enzyme concentration should always be kept constant and the lower limit for determining an IC50 is half of the enzyme concentration

- Well readable and quantifiable screening strategies for measuring the response should be employed. The quantification should be benchmarked under different experimental conditions. For example, cellular viability can be measured by viable cell adenosine triphosphate (ATP) level using the reagent cell titer glo (CTG)

- At least three replicates for each data point should be collected. For cellular viabilities these replicates need to be biological replicates

- Criteria for reporting IC50′s are the maximum % inhibition should be greater than 50%; top and bottom values should be within 15% of theory; the 95% confidence limits for the IC50 should be within a 2–5-fold range. Relative and absolute IC50 and EC50 is described in Figure 3b.

4. HTS Using Pharmaco-Chemical Library

5. Biomarker Prediction

6. IC50 Measurements in Isogenic Settings

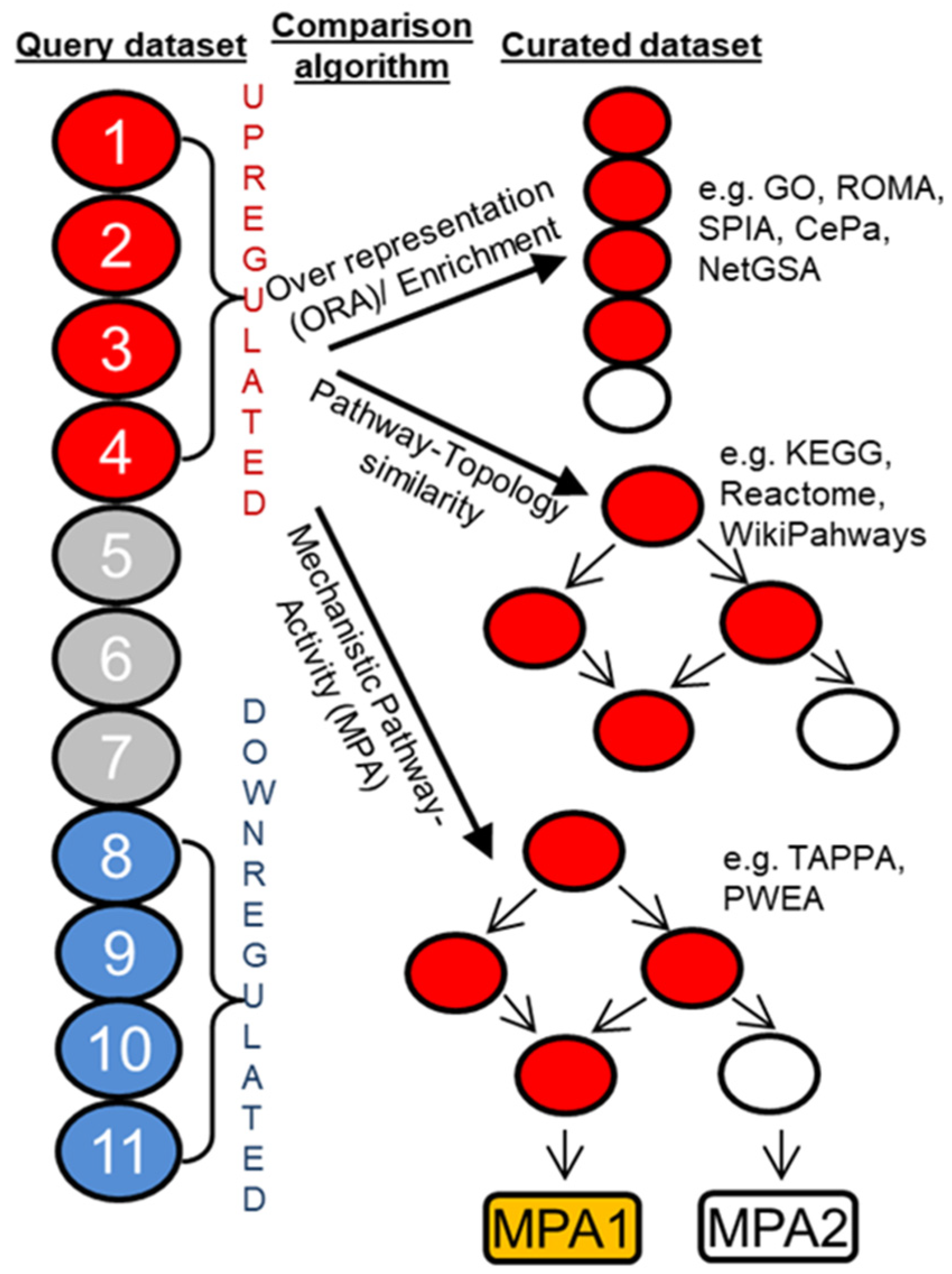

7. Signaling Pathway Analysis and Target Discovery

8. Form Pathway to Target Discovery

9. Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR) and Physicochemical Properties of Drugs

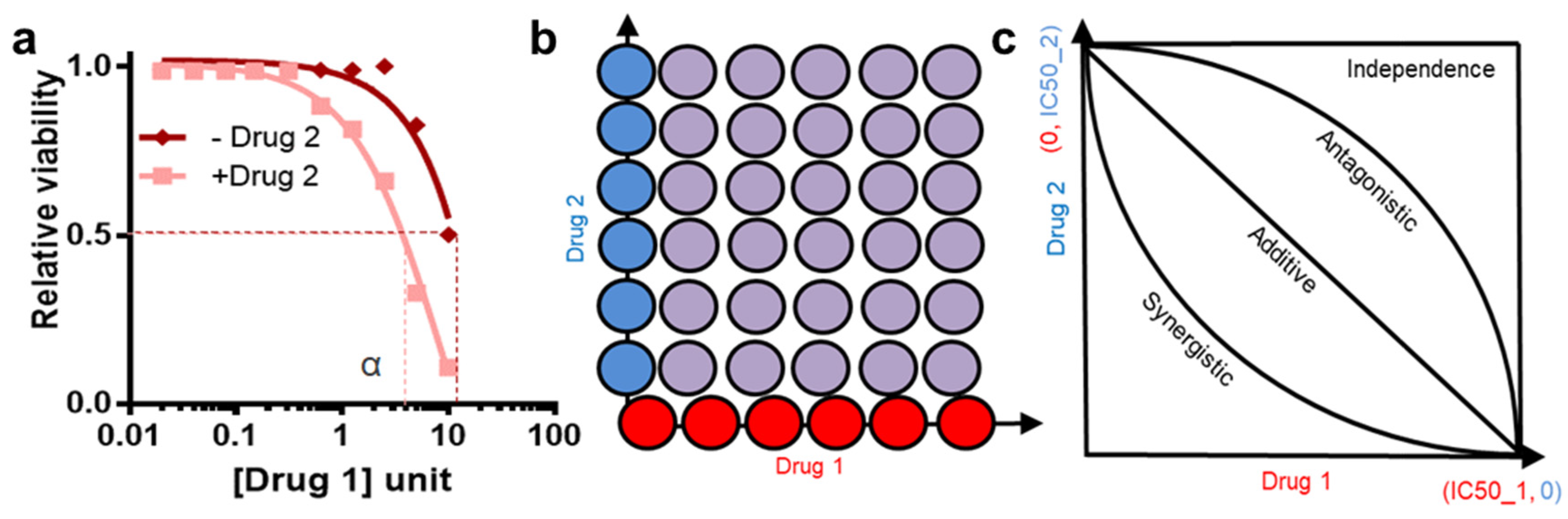

10. Drug Synergy

11. Case Study

12. Bench-to-Bedside Translation

13. Challenges and Scopes

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schrödinger, E. What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell; The University Press: Cambridge, UK; The Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1945; Volume viii, p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J.D.; Crick, F.H. The structure of DNA. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1953, 18, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, H.M.; Mills, G.B.; Ram, P.T. Cancer Systems Biology: A peek into the future of patient care? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11, 167–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viktorsson, K.; Lewensohn, R.; Zhivotovsky, B. Systems biology approaches to develop innovative strategies for lung cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barretina, J.; Caponigro, G.; Stransky, N.; Venkatesan, K.; Margolin, A.A.; Kim, S.; Wilson, C.J.; Lehár, J.; Kryukov, G.V.; Sonkin, D.; et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 2012, 483, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, M.W. The Meaning of Systems Biology. Cell 2005, 121, 503–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuveni, S.; Urbakh, M.; Klafter, J. Role of substrate unbinding in Michaelis–Menten enzymatic reactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4391–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.W.; Niepel, M.; Sorger, P.K. Classic and contemporary approaches to modeling biochemical reactions. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1861–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubig, R.R.; Michael, S.; Terry, K.; Arthur, C.; International Union of Pharmacology Committee on Receptor Nomenclature and Drug Classification. XXXVIII. Update on terms and symbols in quantitative pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003, 55, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markossian, S.; Grossman, A.; Brimacombe, K. (Eds.) Assay Guidance Manual; Bethesda: Rockville, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M.; Watson, I. Standard units for expressing drug concentrations in biological fluids. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1983, 16, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Mshana, R.N.; Miörner, H. Evaluation of a colorimetric assay based on 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) for rapid detection of rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 1998, 2, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Präbst, K.; Engelhardt, H.; Ringgeler, S.; Hübner, H. Basic Colorimetric Proliferation Assays: MTT, WST, and Resazurin. In Cell Viability Assay; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1601, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana, E.A.; Kasinski, A.L. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) Assay in Cell Culture to Investigate Cell Proliferation. Bio-Protocol 2016, 6, e1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, E.A.; Ryu, M.; Diep, C.H.; Mendiratta, S.; Clemenceau, J.R.; Vaden, R.M.; Kim, J.; Motoyaji, T.; Covington, K.R.; Peyton, M.; et al. Chemistry-First Approach for Nomination of Personalized Treatment in Lung Cancer. Cell 2018, 173, 864–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Errico, G.; Machado, H.L.; Sainz, B. A current perspective on cancer immune therapy: Step-by-step approach to constructing the magic bullet. Clin. Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinney, D.C. Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Drug Discovery for First-in-Class Medicines. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 93, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Thorne, N.; McKew, J.C. Phenotypic screens as a renewed approach for drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geysen, H.M.; Meloen, R.H.; Barteling, S.J. Use of peptide synthesis to probe viral antigens for epitopes to a resolution of a single amino acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 3998–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghten, R.A. General method for the rapid solid-phase synthesis of large numbers of peptides: Specificity of antigen-antibody interaction at the level of individual amino acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 5131–5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Li, X.; Lam, K.S. Combinatorial chemistry in drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 38, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Aittokallio, T. Machine learning and feature selection for drug response prediction in precision oncology applications. Biophys. Rev. 2019, 11, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, J.C.; Heiser, L.M.; Georgii, E.; Gönen, M.; Menden, M.P.; Wang, N.J.; Bansal, M.; Ammad-ud-din, M.; Hintsanen, P.; Khan, S.A.; et al. A community effort to assess and improve drug sensitivity prediction algorithms. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, I.S.; Neto, E.C.; Guinney, J.; Friend, S.H.; Margolin, A.A. Systematic assessment of analytical methods for drug sensitivity prediction from cancer cell line data. Biocomputing 2014, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhang, N.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Fang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X. Anticancer drug sensitivity prediction in cell lines from baseline gene expression through recursive feature selection. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hejase, H.; Chan, C. Improving Drug Sensitivity Prediction Using Different Types of Data. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2015, 4, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaCroix, B.; Gamazon, E.R.; Lenkala, D.; Im, H.K.; Geeleher, P.; Ziliak, D.; Cox, N.J.; Huang, R.S. Integrative analyses of genetic variation, epigenetic regulation, and the transcriptome to elucidate the biology of platinum sensitivity. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, L.; Ziliak, D.; Lacroix, B.; Geeleher, P.; Huang, R.S. Integrative “omic” analysis for tamoxifen sensitivity through cell based models. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93420. [Google Scholar]

- Eskiocak, B.; McMillan, E.A.; Mendiratta, S.; Kollipara, R.K.; Zhang, H.; Humphries, C.G.; Wang, C.; Garcia-Rodriguez, J.; Ding, M.; Zaman, A.; et al. Biomarker Accessible and Chemically Addressable Mechanistic Subtypes of BRAF Melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 832–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zu, S.; Gu, J. Evaluating the molecule-based prediction of clinical drug responses in cancer. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2891–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeleher, P.; Cox, N.J.; Huang, R.S. Clinical drug response can be predicted using baseline gene expression levels and in vitro drug sensitivity in cell lines. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeleher, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Gruener, R.F.; Nath, A.; Morrison, G.; Bhutra, S.; Grossman, R.L.; Huang, R.S. Discovering novel pharmacogenomic biomarkers by imputing drug response in cancer patients from large genomics studies. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 1743–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainor, J.F.; Dardaei, L.; Yoda, S.; Friboulet, L.; Leshchiner, I.; Katayama, R.; Dagogo-Jack, I.; Gadgeel, S.; Schultz, K.; Singh, M.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance to First- and Second-Generation ALK Inhibitors in ALK-Rearranged Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 1118–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Parnas, O.; Li, B.; Chen, J.; Fulco, C.P.; Jerby-Arnon, L.; Marjanovic, N.D.; Dionne, D.; Burks, T.; Raychowdhury, R.; et al. Perturb-Seq: Dissecting molecular circuits with scalable single-cell RNA profiling of pooled genetic screens. Cell 2016, 167, 1853–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, B.; Norman, T.M.; Jost, M.; Cho, M.Y.; Nuñez, J.K.; Chen, Y.; Villalta, J.E.; Gilbert, L.A.; Horlbeck, M.A.; Hein, M.Y.; et al. A Multiplexed Single-Cell CRISPR Screening Platform Enables Systematic Dissection of the Unfolded Protein Response. Cell 2016, 167, 1867–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.S.; Wu, H.; Ji, X.; Stelzer, Y.; Wu, X.; Czauderna, S.; Shu, J.; Dadon, D.; Young, R.A.; Jaenisch, R.; et al. Editing DNA Methylation in the Mammalian Genome. Cell 2016, 167, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Sanjana, N.E.; Zheng, K.; Shalem, O.; Lee, K.; Shi, X.; Scott, D.A.; Song, J.; Pan, J.Q.; Weisslederet, R.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen in a mouse model of tumor growth and metastasis. Cell 2015, 160, 1246–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalem, O.; Sanjana, N.E.; Hartenian, E.; Shi, X.; Scott, D.A.; Mikkelson, T.; Heckl, D.; Ebert, B.L.; Root, D.E.; Doench, J.G.; et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 2014, 343, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampmann, M.; Horlbeck, M.A.; Chen, Y.; Tsai, J.C.; Bassik, M.C.; Gilbert, L.A.; Villalta, J.E.; Kwon, S.C.; Chang, H.; Kim, V.N.; et al. Next-generation libraries for robust RNA interference-based genome-wide screens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E3384–E3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampmann, M.; Bassik, M.C.; Weissman, J.S. Functional genomics platform for pooled screening and generation of mammalian genetic interaction maps. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 1825–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Muruganujan, A.; Ebert, D.; Huang, X.; Thomas, P.D. PANTHER version 14: More genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D419–D426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D457–D462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; Viteri, G.; Gong, C.; Lorente, P.; Fabregat, A.; Sidiropoulos, K.; Cook, J.; Gillespie, M.; Haw, R.; et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D498–D503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregat, A.; Jupe, S.; Matthews, L.; Sidiropoulos, K.; Gillespie, M.; Garapati, P.; Haw, R.; Jassal, B.; Korninger, F.; May, B.; et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D649–D655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.Y.; Tan, C.M.; Kou, Y.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Meirelles, G.V.; Clark, N.R.; Ma’ayan, A. Enrichr: Interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberzon, A.; Birger, C.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Ghandi, M.; Mesirov, J.P.; Tamayo, P. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberzon, A.; Subramanian, A.; Pinchback, R.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Tamayo, P.; Mesirov, J.P. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1739–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martignetti, L.; Calzone, L.; Bonnet, E.; Barillot, E.; Zinovyev, A. ROMA: Representation and Quantification of Module Activity from Target Expression Data. Front. Genet. 2016, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarca, A.L.; Draghici, S.; Khatri, P.; Hassan, S.S.; Mittal, P.; Kim, J.; Kim, C.J.; Kusanovic, J.P.; Romero, R. A novel signaling pathway impact analysis. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Wang, J. CePa: An R package for finding significant pathways weighted by multiple network centralities. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Shojaie, A.; Michailidis, G. Network-based pathway enrichment analysis with incomplete network information. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3165–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutmon, M.; Riutta, A.; Nunes, N.; Hanspers, K.; Willighagen, E.L.; Bohler, A.; Mélius, J.; Waagmeester, A.; Sinha, S.R.; Miller, R.; et al. WikiPathways: Capturing the full diversity of pathway knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D488–D494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, X. TAPPA: Topological analysis of pathway phenotype association. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 3100–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.-H.; Whitfield, T.W.; Yang, T.-H.; Hu, Z.; Weng, Z.; DeLisi, C. Identification of functional modules that correlate with phenotypic difference: The influence of network topology. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Shafi, A.; Nguyen, T.; Draghici, S. Identifying significantly impacted pathways: A comprehensive review and assessment. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadoz, A.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Çubuk, C.; Carbonell-Caballero, J.; Dopazo, J. A comparison of mechanistic signaling pathway activity analysis methods. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1655–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.Y.; Zhang, H.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M. Molecular docking: A powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2011, 7, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, L.A.; Horlbeck, M.A.; Adamson, B.; Villalta, J.E.; Chen, Y.; Whitehead, E.H.; Guimaraes, C.; Panning, B.; Ploegh, H.L.; Bassik, M.C.; et al. Genome-Scale CRISPR-Mediated Control of Gene Repression and Activation. Cell 2014, 159, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, A. Docking studies and network analyses reveal capacity of compounds from Kandelia rheedii to strengthen cellular immunity by interacting with host proteins during tuberculosis infection. Bioinformation 2012, 8, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, M.A. Target discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagadala, N.S.; Syed, K.; Tuszynski, J. Software for molecular docking: A review. Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasov, A.; Muratov, N.A.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A.; Baskin, I.I.; Cronin, M.; Dearden, J.; Gramatica, P.; Martin, Y.C.; Todeschini, R.; et al. QSAR modeling: Where have you been? Where are you going to? J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4977–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.E.; Hansch, C. Correlation of physicochemical parameters and biological activity in steroids 9α-substituted cortisol derivatives. Experientia 1973, 29, 1111–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, M.; Gautam, R.K. Synthesis and Biological Activities of Substituted 4,4,4-Trifluoro-3-(indoIe-3-) butyric Acids, Novel Fluorinated Plant Growth Regulators. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1996, 60, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.R.; Zaman, A.; Jahan, I.; Chakravorty, R.; Chakraborty, S. In silico QSAR analysis of quercetin reveals its potential as therapeutic drug for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Young Pharm. 2013, 5, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucquier, J.; Guedj, M. Analysis of drug combinations: Current methodological landscape. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2015, 3, e00149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.C.; Sorger, P.K. Combination Cancer Therapy Can Confer Benefit via Patient-to-Patient Variability without Drug Additivity or Synergy. Cell 2017, 171, 1678–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, K.N.; Bhatt, R.; Rotow, J.; Rohrberg, J.; Olivas, V.; Wang, V.E.; Hemmati, G.; Martins, M.M.; Maynard, A.; Kuhn, J.; et al. Aurora kinase A drives the evolution of resistance to third-generation EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.E.; Xue, J.Y.; Frederick, D.T.; Cao, Y.; Lin, E.; Wilson, C.; Urisman, A.; Carbone, D.P.; Flaherty, K.T.; Bernards, R.; et al. Adaptive Resistance to Dual BRAF/MEK Inhibition in BRAF-Driven Tumors through Autocrine FGFR Pathway Activation. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2019, 25, 7202–7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Sabnis, A.J.; Chan, E.; Olivas, V.; Cade, L.; Pazarentzos, E.; Asthana, S.; Neel, D.; Yan, J.J.; Lu, X.; et al. The Hippo effector YAP promotes resistance to RAF- and MEK-targeted cancer therapies. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.; Wennerberg, K.; Aittokallio, T.; Tang, J. Searching for Drug Synergy in Complex Dose-Response Landscapes Using an Interaction Potency Model. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.C.; Chidley, C.; Sorger, P.K. A curative combination cancer therapy achieves high fractional cell killing through low cross-resistance and drug additivity. eLife 2019, 8, e50036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddum, J.H. Discoveries in therapeutics. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1954, 6, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabovsky, Y.; Tallarida, R. Isobolographic Analysis for Combinations of a Full and Partial Agonist: Curved Isoboles. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 310, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, T.-C. Theoretical Basis, Experimental Design, and Computerized Simulation of Synergism and Antagonism in Drug Combination Studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 621–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, W.R.; Bravo, G.; Parsons, J.C. The search for synergy: A critical review from a response surface perspective. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995, 47, 331–385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loewe, S. Effect of combinations: Mathematical basis of problem. Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 1926, 114, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.C.; Talalay, P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: The combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1984, 22, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, M.J.; Edelman, E.J.; Heidorn, S.J.; Greenman, C.D.; Dastur, A.; Lau, K.W.; Greninger, P.; Thompson, I.R.; Luo, X.; Soares, J.; et al. Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature 2012, 483, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPage, M.; Dooley, A.L.; Jacks, T. Conditional mouse lung cancer models using adenoviral or lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.T.; Alférez, D.G.; Amant, F.; Annibali, D.; Arribas, J.; Biankin, A.V.; Bruna, A.; Budinská, E.; Caldas, C.; Chang, D.K.; et al. Interrogating open issues in cancer precision medicine with patient-derived xenografts. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.; Bivona, T.G. Emerging application of genomics-guided therapeutics in personalized lung cancer treatment. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Mendiratta, S.; Kim, J.; Pecot, C.V.; Larsen, J.E.; Zubovych, I.; Seo, B.Y.; Kim, J.; Eskiocak, B. Systematic identification of molecular subtype-selective vulnerabilities in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cell 2013, 155, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, R.J.; Haderk, F.; Stahlhut, C.; Schulze, C.J.; Hemmati, G.; Wildes, D.; Tzitzilonis, C.; Mordec, K.; Marquez, A.; Romero, J.; et al. RAS nucleotide cycling underlies the SHP2 phosphatase dependence of mutant BRAF-, NF1- and RAS-driven cancers. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lux, L.J.; Posey, R.E.; Daniels, L.S.; Henke, D.C.; Durham, C.; Jonas, D.E.; Lohr, K.N. Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Measures for Guiding Antibiotic Treatment for Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, D.R.; Krummel, M.F.; Allison, J.P. Enhancement of Antitumor Immunity by CTLA-4 Blockade. Science 1996, 271, 1734–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, B.W.; Allison, J. The mouse T cell receptor: Structural heterogeneity of molecules of normal T cells defined by Xenoantiserum. Cell 1983, 34, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haibe-Kains, B.; El-Hachem, N.; Birkbak, N.J.; Jin, A.C.; Beck, A.H.; Aerts, H.; Quackenbush, J. Inconsistency in large pharmacogenomic studies. Nature 2013, 504, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Better support translational research. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 1333. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, K.K.; Cattaneo, C.M.; Weeber, F.; Chalabi, M.; Haar, J.V.; Fanchi, L.F.; Slagter, M.; Velden, D.L.; Kaing, S.; Kelderman, S.; et al. Generation of Tumor-Reactive T Cells by Co-culture of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes and Tumor Organoids. Cell 2018, 174, 1586–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivona, T.G.; Doebele, R.C. A framework for understanding and targeting residual disease in oncogene-driven solid cancers. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, C.M.; Watkins, T.B.K.; Wu, W.; Gini, B.; Chabon, J.J.; McCoach, C.E.; McGranahan, N.; Wilson, G.A.; Birkbak, N.J.; Olivas, V.; et al. Evolution and clinical impact of co-occurring genetic alterations in advanced-stage EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1693–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, M.; Rowan, A.J.; Horswell, S.; Math, M.; Larkin, J.; Endesfelder, D.; Gronroos, E.; Martinez, P.; Matthews, N.; Stewart, A.; et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.; Wu, W.; Bivona, T.G. Targeting Oncogenic BRAF: Past, Present, and Future. Cancers 2019, 11, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phenotypic Screening | Target Based Screening | |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular targets | Not known | Known |

| MOA | Not known, but can be targeted based on signaling pathways | Known |

| Assay type | Cell viability (e.g., luminescence read out live cells) | Direct binding assays (e.g., fluorescence read out in FRET) |

| Assay scale | Relatively difficult to scale up | Easily scalable into high throughput |

| Biological relevance | Highly relevant to biology | May not be relevant to functional biology |

| Quantification methods | Not available | Structure activity relationship (SAR) |

| Novel target scope | High | Low |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaman, A.; Bivona, T.G. Quantitative Framework for Bench-to-Bedside Cancer Research. Cancers 2022, 14, 5254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215254

Zaman A, Bivona TG. Quantitative Framework for Bench-to-Bedside Cancer Research. Cancers. 2022; 14(21):5254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215254

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaman, Aubhishek, and Trever G. Bivona. 2022. "Quantitative Framework for Bench-to-Bedside Cancer Research" Cancers 14, no. 21: 5254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215254

APA StyleZaman, A., & Bivona, T. G. (2022). Quantitative Framework for Bench-to-Bedside Cancer Research. Cancers, 14(21), 5254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215254