Predictors of Survival in Elderly Patients with Metastatic Colon Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Treatment

3.3. Survival and Prognostic Factors

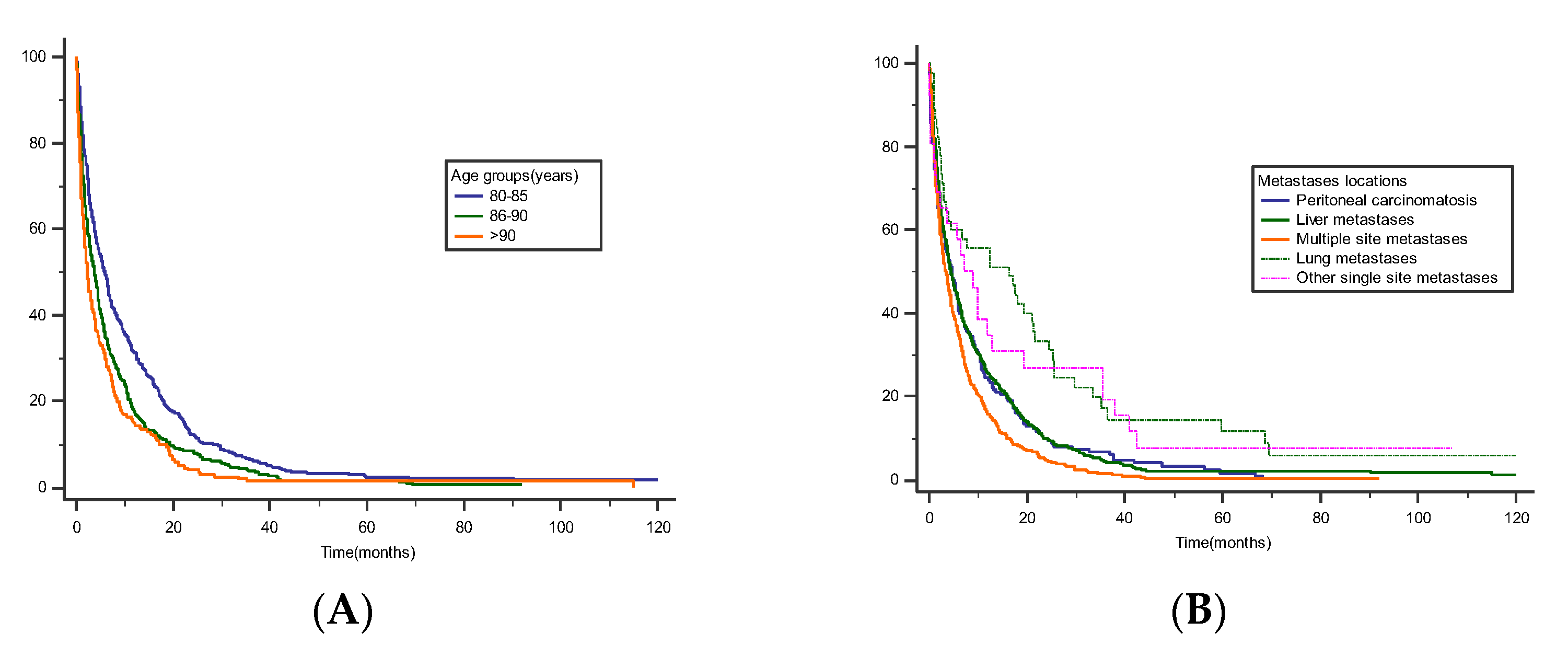

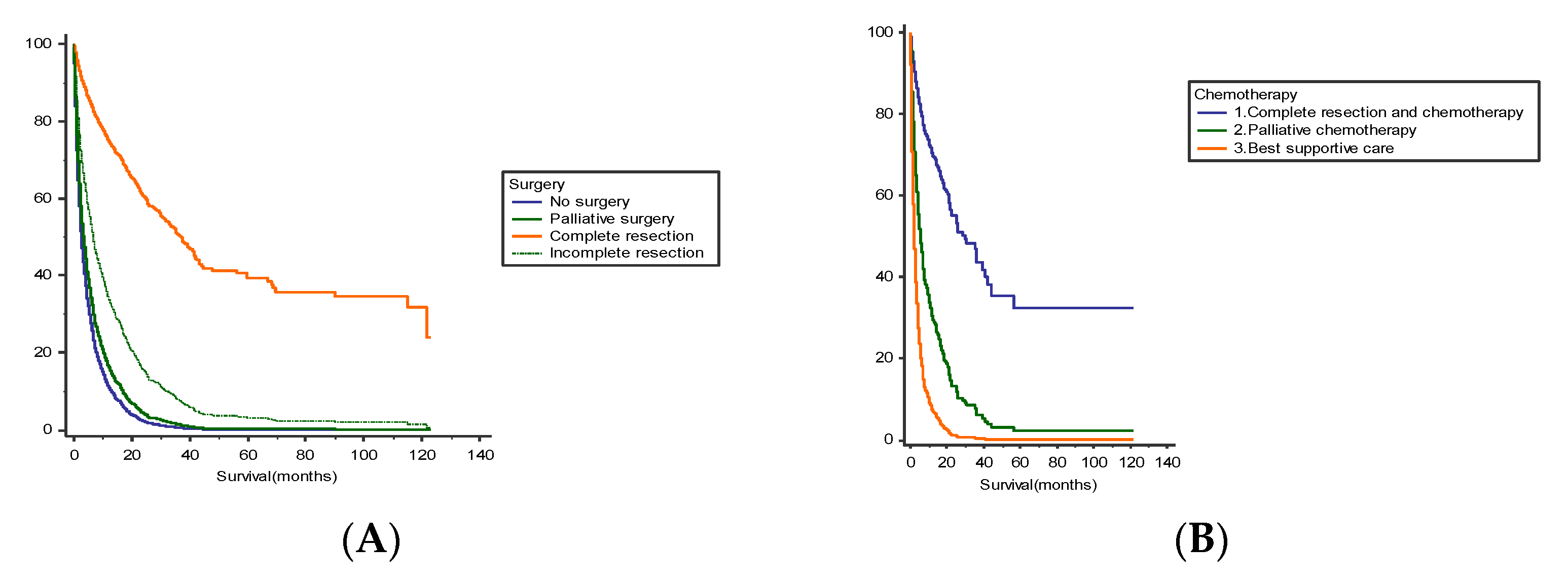

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission B. Population Structure and Ageing. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_ageing (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Sauer, A.G.; Fedewa, S.A.; Butterly, L.F.; Anderson, J.C.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defossez, G.; Uhry, Z.; Delafosse, P.; Dantony, E.; D’Almeida, T.; Plouvier, S.; Bossard, N.; Bouvier, A.M.; Molinié, F.; Woronoff, A.S.; et al. Cancer incidence and mortality trends in France over 1990–2018 for solid tumors: The sex gap is narrowing. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusselaers, N.; Lagergren, J. The Charlson Comorbidity Index in Registry-based Research. Methods Inf. Med. 2017, 56, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.N.; Wu, D.S.; Stiegmann, G.V.; Moss, M. Frailty predicts increased hospital and six-month healthcare cost following colorectal surgery in older adults. Am. J. Surg. 2011, 202, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.; Nielsen, D.; Dehlendorff, C.; Christiansen, A.; Rønholt, F.; Johansen, J.; Vistisen, K. Efficacy and toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: The ACCORE study. ESMO Open 2016, 1, e000087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvier, A.-M.; Jooste, V.; Sanchez-Perez, M.J.; Bento, M.J.; Rodrigues, J.R.; Marcos-Gragera, R.; Carmona-Garcia, M.C.; Luque-Fernandez, M.A.; Minicozzi, P.; Bouvier, V.; et al. Differences in the management and survival of metastatic colorectal cancer in Europe. A population-based study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinoso-Imran, A.Q.; O’Rorke, M.; Kee, F.; Jordao, H.; Walls, G.; Bannon, F.J. Surgical under-treatment of older adult patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowsky, D.J.; Olshansky, S.J.; Bhattacharya, J.; Goldman, D.P. Heterogeneity in healthy aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biller, L.H.; Schrag, D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De’Angelis, N.; Baldini, C.; Brustia, R.; Pessaux, P.; Sommacale, D.; Laurent, A.; Le Roy, B.; Tacher, V.; Kobeiter, H.; Luciani, A.; et al. Surgical and regional treatments for colorectal cancer metastases in older patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, P.; Best, L.; George, S.; Baughan, C.; Buchanan, R.; Davis, C.; Fentiman, I.; Gosney, M.; Northover, J.; Williams, C. Surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: A systematic review. Lancet 2000, 356, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, J.W.T.; van den Broek, C.B.; Bastiaannet, E.; van de Geest, L.G.; Tollenaar, R.A.; Liefers, G.J. Importance of the first postoperative year in the prognosis of elderly colorectal cancer patients. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 1533–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.; Frilling, A.; Elias, D.; Laurent, C.; Ramos, E.; Capussotti, L.; Poston, G.J.; Wicherts, D.A.; de Haas, R.J. Liver resection of colorectal metastases in elderly patients. Br. J. Surg. 2010, 97, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Lai, B. Metastatic patterns and survival outcomes in patients with stage IV colon cancer: A population-based analysis. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, T.; Karapetis, C.S.; Roder, D.; Tie, J.; Padbury, R.; Price, T.; Wong, R.; Shapiro, J.; Nott, L.; Lee, M.; et al. The survival outcome of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer based on the site of metastases and the impact of molecular markers and site of primary cancer on metastatic pattern. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 1438–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunitake, H.; Zingmond, D.S.; Ryoo, J.; Ko, C.Y. Caring for octogenarian and nonagenarian patients with colorectal cancer: What should our standards and expectations be? Dis. Colon Rectum 2010, 53, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugen, N.; Nagtegaal, I.D. Distinct metastatic patterns in colorectal cancer patients based on primary tumour location. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 75, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costi, R.; Leonardi, F.; Zanoni, D.; Violi, V.; Roncoroni, L. Palliative care and end-stage colorectal cancer management: The surgeon meets the oncologist. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 7602–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohman, U. Prognosis in patients with obstructing colorectal carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 1982, 143, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, M.; Zorcolo, L.; Merli, C.; Cimbanassi, S.; Poiasina, E.; Ceresoli, M.; Agresta, F.; Allievi, N.; Bellanova, G.; Coccolini, F.; et al. 2017 WSES guidelines on colon and rectal cancer emergencies: Obstruction and perforation. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2018, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, M.T.; Thompson, L.C.; Wasan, H.S.; Middleton, G.; Brewster, A.E.; Shepherd, S.F.; O’Mahony, M.S.; Maughan, T.S.; Parmar, M.; Langley, R.E.; et al. Chemotherapy options in elderly and frail patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MRC FOCUS2): An open-label, randomised facto-rial trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 9779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faivre-Finn, C.; Bouvier-Benhamiche, A.-M.; Phelip, J.M.; Manfredi, S.; Dancourt, V.; Faivre, J. Colon cancer in France: Evidence for improvement in management and survival. Gut 2002, 51, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichael, D.; Lopes, G.S.; Olswold, C.L.; Douillard, J.-Y.; Adams, R.A.; Maughan, T.S.; Van Cutsem, E.; Venook, A.P.; Lenz, H.-J.; Heinemann, V.; et al. Efficacy of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor agents in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer ≥70 years. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 163, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, E.; Kowal, P.; Hoogendijk, E.O. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: A review. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilabert, M.; Ries, P.; Chanez, B.; Triby, S.; Francois, E.; Lièvre, A.; Rousseau, F. Place of anti-EGFR therapy in older patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in 2020. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2020, 11, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taieb, J. How best to treat older patients with metastatic colorectal cancer? Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, D.; Lang, I.; Marcuello, E.; Lorusso, V.; Ocvirk, J.; Shin, D.B.; Jonker, D.; Osborne, S.; Andre, N.; Waterkamp, D.; et al. Bevacizumab plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in elderly patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer (AVEX): An open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M.G. Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Current State and Future Directions. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1809–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio, T.; Jouve, J.-L.; Teillet, L.; Gargot, D.; Subtil, F.; Le Brun-Ly, V.; Cretin, J.; Locher, C.; Bouché, O.; Breysacher, G.; et al. Geriatric Factors Predict Chemotherapy Feasibility: Ancillary Results of FFCD 2001-02 Phase III Study in First-Line Chemotherapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in Elderly Patients. JCO 2013, 31, 1464–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N = 1115 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 495 (44%) |

| Female | 620 (56%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 85.0 (range 80.0, 103.1) |

| Primary tumor location (unknown 52 patients) | |

| Proximal Colon | 611 (54.7%) |

| Distal Colon | 452 (40.5%) |

| Presenting features | |

| Symptoms | 733 (65.7%) |

| Emergency | 275 (24.6%) |

| Fortuitous | 97 (8.6%) |

| Unknown | 10 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score (unknown 61 patients) | |

| 0 | 509 (45.6%) |

| 1 | 296 (26.5%) |

| 2 | 143 (12.8%) |

| ≥3 | 106 (9.5%) |

| Metastatic sites (unknown 1 patient) | |

| Liver | 452 (40.5%) |

| Lungs | 45 (4.0%) |

| Peritoneum | 182 (16.3%) |

| Other (single location) | 26 (2.3%) |

| Multiple locations | 409 (36.6%) |

| Treatment | |

| Best supportive care | 535 (48%) |

| Chemotherapy | 237 (21.2%) |

| Palliative | 79 (7%) |

| Postoperative (unknown 10 patients) | 158 (14.1%) |

| Surgery | |

| Complete resection of primary tumor and metastases | 23 (2%) |

| Complete resection of primary tumor | 251 (22.4%) |

| Partial resection of primary tumor and metastases * | 214 (19.1%) |

| Palliative surgery (surgical bypass, diverting ostomy) | 112 (10%) |

| Exploratory laparotomy | 29 (2.5%) |

| Characteristics | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR 1 | 95% CI 1 | p-Value | HR 1 | 95% CI 1 | p-Value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | — | — | ||||

| Female | 1.10 | 0.98, 1.24 | 0.12 | |||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||

| 80–85 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 86–90 | 1.35 | 1.18, 1.54 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 0.91, 1.35 | 0.3 |

| ≥90 | 1.65 | 1.40, 1.90 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 0.82, 1.30 | 0.8 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||||||

| 0 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1 | 0.84 | 0.73, 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.77 | 0.69, 0.91 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 1.04 | 0.86, 1.25 | 0.7 | 0.98 | 0.80, 1.21 | 0.9 |

| ≥3 | 1.19 | 0.96, 1.47 | 0.11 | 1.06 | 0.84, 1.34 | 0.6 |

| Emergency symptoms | ||||||

| No | — | — | ||||

| Yes | 0.96 | 0.84, 1.11 | 0.6 | |||

| Primary tumour location | ||||||

| Proximal | — | — | ||||

| Distal | 0.89 | 0.79, 1.01 | 0.068 | |||

| Metastasis sites | ||||||

| Liver | — | — | — | — | ||

| Lungs | 0.56 | 0.40, 0.77 | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.32, 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Peritoneum | 1.04 | 0.87, 1.23 | 0.7 | 0.99 | 0.81, 1.21 | >0.9 |

| Other (single location) | 0.64 | 0.42, 0.96 | 0.033 | 0.74 | 0.48, 1.14 | 0.2 |

| Multiple locations | 1.32 | 1.15, 1.51 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 1.10, 1.51 | 0.001 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Best supportive care | — | — | — | — | ||

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | 0.23 | 0.19, 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.13, 0.21 | <0.001 |

| Palliative chemotherapy | 0.45 | 0.35, 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.31, 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Surgery | ||||||

| Complete resection of primary tumor and metastases | 0.24 | 0.14, 0.41 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 0.24, 0.38 | <0.001 |

| Complete resection of primary tumor | 0.82 | 0.68, 0.99 | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.39, 0.54 | <0.001 |

| Partial resection of primary tumor and metastases | 0.56 | 0.48, 0.66 | <0.001 | 0.62 | 0.53, 0.74 | <0.001 |

| Palliative surgery (surgical bypass, diverting ostomy) | 0.75 | 0.52, 1.1 | 0.14 | 0.73 | 0.59, 0.90 | 0.04 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Badic, B.; Bouvier, A.-M.; Bouvier, V.; Morvan, M.; Jooste, V.; Alves, A.; Nousbaum, J.-B.; Reboux, N. Predictors of Survival in Elderly Patients with Metastatic Colon Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 5208. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215208

Badic B, Bouvier A-M, Bouvier V, Morvan M, Jooste V, Alves A, Nousbaum J-B, Reboux N. Predictors of Survival in Elderly Patients with Metastatic Colon Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Cancers. 2022; 14(21):5208. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215208

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadic, Bogdan, Anne-Marie Bouvier, Véronique Bouvier, Marie Morvan, Valérie Jooste, Arnaud Alves, Jean-Baptiste Nousbaum, and Noémi Reboux. 2022. "Predictors of Survival in Elderly Patients with Metastatic Colon Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study" Cancers 14, no. 21: 5208. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215208

APA StyleBadic, B., Bouvier, A.-M., Bouvier, V., Morvan, M., Jooste, V., Alves, A., Nousbaum, J.-B., & Reboux, N. (2022). Predictors of Survival in Elderly Patients with Metastatic Colon Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Cancers, 14(21), 5208. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215208