The Effects of a Mediterranean Diet Intervention on Cancer-Related Fatigue for Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. MedDiet Intervention

2.5. Control Arm

2.6. Measures

2.7. Sample Size Determination and Statistical Analysis

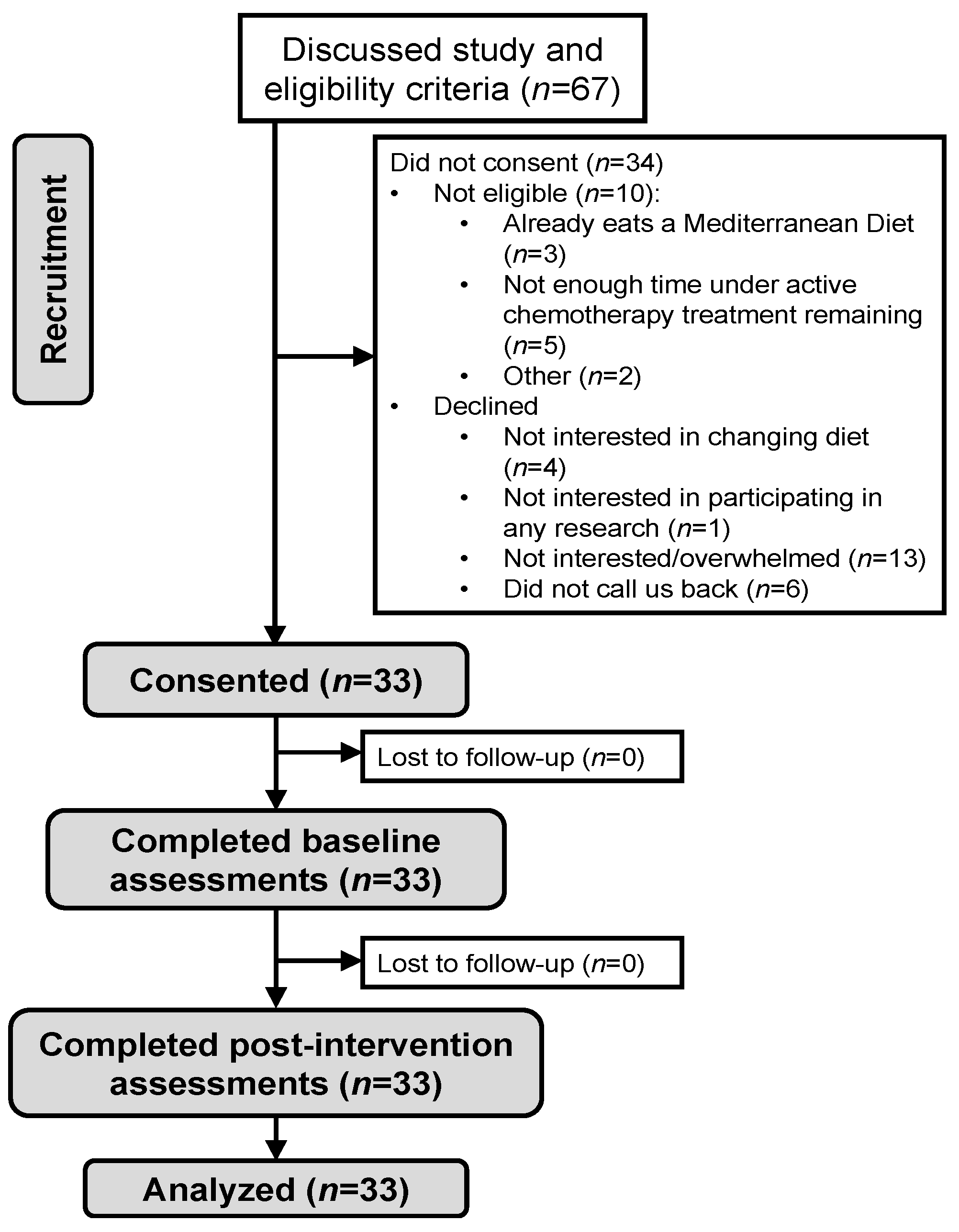

3. Results

3.1. Population

3.2. Feasibility, Dietary Adherence, and Safety

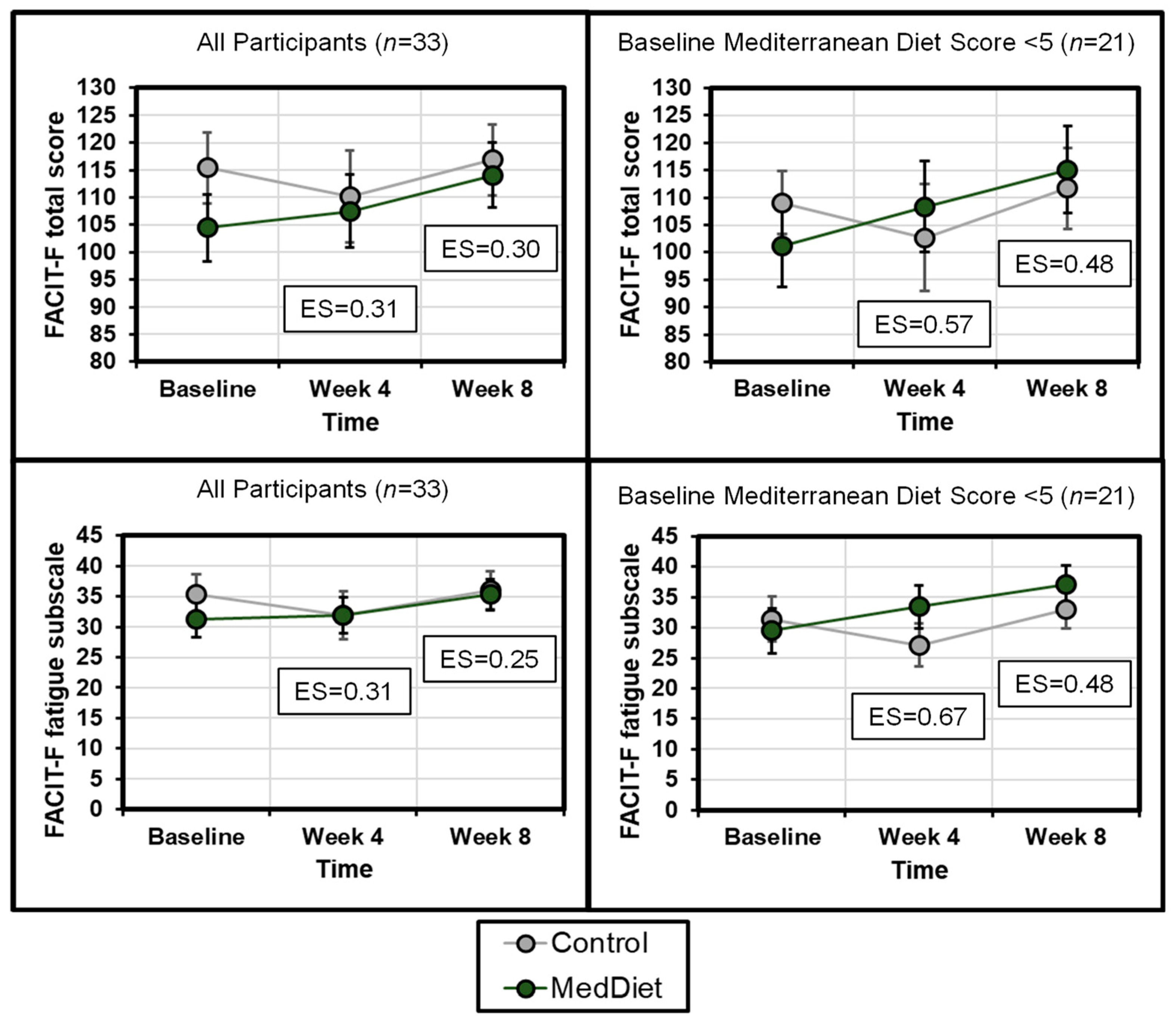

3.3. Cancer-Related Fatigue

3.4. Metabolic and Mitochondrial Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Berger, A.M.; Mooney, K.; Alvarez-Perez, A.; Breitbart, W.S.; Carpenter, K.M.; Cella, D.; Cleeland, C.; Dotan, E.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Escalante, C.P.; et al. Cancer-Related Fatigue, Version 2.2015, Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Nat. Comp. Cancer Netw. 2015, 13, 1012–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Al Sinani, M.; Al Naamani, Z.; Al Badi, K.; Tanash, M.I. Prevalence of Fatigue in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pain. Symptom. Manag. 2021, 61, 167–189.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servaes, P.; Verhagen, C.; Bleijenberg, G. Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment: Prevalence, correlates and interventions. Eur. J. Cancer 2002, 38, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.E. Cancer-related fatigue—mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleight, A.G.; Crowder, S.L.; Skarbinski, J.; Coen, P.; Parker, N.H.; Hoogland, A.I.; Gonzalez, B.D.; Playdon, M.C.; Cole, S.; Ose, J.; et al. A New Approach to Understanding Cancer-Related Fatigue: Leveraging the 3P Model to Facilitate Risk Prediction and Clinical Care. Cancers 2022, 14, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.E. The role of neuro-immune interactions in cancer-related fatigue: Biobehavioral risk factors and mechanisms. Cancer 2019, 125, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saligan, L.N.; Olson, K.; Filler, K.; Larkin, D.; Cramp, F.; Yennurajalingam, S.; Escalante, C.P.; del Giglio, A.; Kober, K.M.; Kamath, J.; et al. The biology of cancer-related fatigue: A review of the literature. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 2461–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chu, S.; Gao, Y.; Ai, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, N. A Narrative Review of Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF) and Its Possible Pathogenesis. Cells 2019, 8, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorini, S.; De Angelis, A.; Berrino, L.; Malara, N.; Rosano, G.; Ferraro, E. Chemotherapeutic Drugs and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Focus on Doxorubicin, Trastuzumab, and Sunitinib. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7582730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, J.E.; Lin, P.J.; Kerns, S.L.; Kleckner, I.R.; Kleckner, A.S.; Castillo, D.A.; Mustian, K.M.; Peppone, L.J. Nutritional Interventions for Treating Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Qualitative Review. Nutr. Cancer 2019, 71, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguley, B.J.; Skinner, T.L.; Wright, O.R.L. Nutrition therapy for the management of cancer-related fatigue and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 122, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleckner, A.S.; van Wijngaarden, E.; Jusko, T.A.; Kleckner, I.R.; Lin, P.-J.; Mustian, K.M.; Peppone, L.J. Serum Carotenoids and Cancer-Related Fatigue: An Analysis of the 2005–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Cancer Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.S.; Rice, N.; Kingston, E.; Kelly, A.; Reynolds, J.V.; Feighan, J.; Power, D.G.; Ryan, A.M. A national survey of oncology survivors examining nutrition attitudes, problems and behaviours, and access to dietetic care throughout the cancer journey. Clin. Nutr. Espen. 2021, 41, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosone, C.B.; Zirpoli, G.R.; Hutson, A.D.; McCann, W.E.; McCann, S.E.; Barlow, W.E.; Kelly, K.M.; Cannioto, R.; Sucheston-Campbell, L.E.; Hershman, D.L.; et al. Dietary supplement use during chemotherapy and survival outcomes of patients with breast cancer enrolled in a cooperative group clinical trial (SWOG S0221). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapidari, P.; Djehal, N.; Havas, J.; Gbenou, A.; Martin, E.; Charles, C.; Dauchy, S.; Pistilli, B.; Cadeau, C.; Bertaut, A.; et al. Determinants of use of oral complementary-alternative medicine among women with early breast cancer: A focus on cancer-related fatigue. Breast. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 190, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustian, K.M.; Alfano, C.M.; Heckler, C.; Kleckner, A.S.; Kleckner, I.R.; Leach, C.R.; Mohr, D.; Palesh, O.G.; Peppone, L.J.; Piper, B.F.; et al. Comparison of Pharmaceutical, Psychological, and Exercise Treatments for Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguley, B.J.; Skinner, T.L.; Jenkins, D.G.; Wright, O.R.L. Mediterranean-style dietary pattern improves cancer-related fatigue and quality of life in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy: A pilot randomised control trial. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.C.; McIntosh, M.K. Potential mechanisms by which polyphenol-rich grapes prevent obesity-mediated inflammation and metabolic diseases. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2011, 31, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Shen, W.; Yu, G.; Jia, H.; Li, X.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Weber, P.; Wertz, K.; Sharman, E.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial function in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; He, X.W.; Jiang, J.G.; Xu, X.L. Hydroxytyrosol and its potential therapeutic effects. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2014, 62, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, I.K.; Benn, E.K.; Fabian, M.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Digga, E.; Deshpande, R.; Miller, A.; Gallo, S.; Arab, L. Randomized-controlled trial of a modified Mediterranean dietary program for multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2019, 36, 101403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Garcia, E.; Hagan, K.A.; Fung, T.T.; Hu, F.B.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F. Mediterranean diet and risk of frailty syndrome among women with type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnolo, N.; Johnston, S.; Collatz, A.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Dietary and nutrition interventions for the therapeutic treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: A systematic review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F.; Pellegrini, N.; Vannini, L.; Jeffery, I.B.; La Storia, A.; Laghi, L.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ferrocino, I.; Lazzi, C.; et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut 2016, 65, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, U.; Herpich, C.; Norman, K. Anti-Inflammatory Diets and Fatigue. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koebnick, C.; Black, M.H.; Wu, J.; Shu, Y.H.; MacKay, A.W.; Watanabe, R.M.; Buchanan, T.A.; Xiang, A.H. A diet high in sugar-sweetened beverage and low in fruits and vegetables is associated with adiposity and a pro-inflammatory adipokine profile. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanini, M.Z.; Guallar-Castillon, P.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Mediterranean Diet and Changes in Sleep Duration and Indicators of Sleep Quality in Older Adults. Sleep 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarupski, K.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Li, H.; Evans, D.A.; Morris, M.C. Mediterranean diet and depressive symptoms among older adults over time. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2013, 17, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, L.; Owen, L.; Kras, M.; Scholey, A. Behavioural effects of a 10-day Mediterranean diet. Results from a pilot study evaluating mood and cognitive performance. Appetite 2011, 56, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Garcia-Arellano, A.; Toledo, E.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Corella, D.; Covas, M.I.; Schroder, H.; Aros, F.; Gomez-Gracia, E.; et al. A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: The PREDIMED trial. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inf. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundacion Dieta Mediterranea. The Pyramid. Available online: https://dietamediterranea.com/en/ (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Djuric, Z.; Vanloon, G.; Radakovich, K.; Dilaura, N.M.; Heilbrun, L.K.; Sen, A. Design of a Mediterranean exchange list diet implemented by telephone counseling. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahn, J.M.; Reeves, R.S.; Keim, K.S.; Laquatra, I.; Kellogg, M.; Jortberg, B.; Clark, N.A. State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An) scale: A new tool for the assessment of outcomes in cancer anemia and fatigue. Semin. Hematol. 1997, 34, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, T.R.; Wang, X.S.; Cleeland, C.S.; Morrissey, M.; Johnson, B.A.; Wendt, J.K.; Huber, S.L. The Rapid Assessment of Fatigue Severity in Cancer Patients. Cancer 1999, 85, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE); UpToDate: Waltham, MA, USA, 2017; version 5.0.

- Zick, S.M.; Sen, A.; Han-Markey, T.L.; Harris, R.E. Examination of the association of diet and persistent cancer-related fatigue: A pilot study. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2013, 40, E41–E49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouroliakou, M.; Grosomanidis, D.; Massara, P.; Kostara, C.; Papandreou, P.; Ntountaniotis, D.; Xepapadakis, G. Serum antioxidant capacity, biochemical profile and body composition of breast cancer survivors in a randomized Mediterranean dietary intervention study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2133–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, M.A. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K. Alternatives to P value: Confidence interval and effect size. Korean J. Anesth. 2016, 69, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashi, P.; Edwin, P.; Popiel, B.; Lammersfeld, C.; Gupta, D. Methylmalonic Acid and Homocysteine as Indicators of Vitamin B-12 Deficiency in Cancer. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, E.; Montagnana, M.; Nouvenne, A.; Lippi, G. Advantages and pitfalls of fructosamine and glycated albumin in the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015, 9, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioxari, A.; Tzanos, D.; Kostara, C.; Papandreou, P.; Mountzios, G.; Skouroliakou, M. Mediterranean Diet Implementation to Protect against Advanced Lung Cancer Index (ALI) Rise: Study Design and Preliminary Results of a Randomised Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarini, A.; Pasanisi, P.; Raimondi, M.; Gargano, G.; Bruno, E.; Morelli, D.; Evangelista, A.; Curtosi, P.; Berrino, F. Preventing weight gain during adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: A dietary intervention study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 135, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, S.M.; Abdollahi, M.; Hosseini, A.; Bozorg, D.K.; Ajami; Azadeh, M.; Moiniafshar, K. The positive effects of Mediterranean-neutropenic diet on nutritional status of acute myeloid leukemia patients under chemotherapy. Front. Biol. 2018, 13, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pitsavos, C.; Arvaniti, F.; Stefanadis, C. Adherence to the Mediterranean food pattern predicts the prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and obesity, among healthy adults; the accuracy of the MedDietScore. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, A.; Taft, C.; Lundgren-Nilsson, A.; Dencker, A. Minimal important differences for fatigue patient reported outcome measures-a systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, C.R.; Johansson, B.B.K.; Sjoden, P.-O.; Glimelius, B.L.G. A randomized study of nutritional support in patients with colorectal and gastric cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2002, 42, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravasco, P.; Monteiro-Grillo, I.; Marques Vidal, P.; Camilo, M.E. Impact of nutrition on outcome: A prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiotherapy. Head. Neck. 2005, 27, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravasco, P.; Monteiro-Grillo, I.; Vidal, P.M.; Camilo, M.E. Dietary counseling improves patient outcomes: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial in colorectal cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvers, M.A.; Savva, J.; Huggins, C.E.; Truby, H.; Haines, T. Potential benefits of early nutritional intervention in adults with upper gastrointestinal cancer: A pilot randomised trial. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 3035–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filler, K.; Lyon, D.; Bennett, J.; McCain, N.; Elswick, R.; Lukkahatai, N.; Saligan, L.N. Association of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Fatigue: A Review of the Literature. BBA Clin. 2014, 1, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, J.C.; Cheregi, B.D.; Timpani, C.A.; Nurgali, K.; Hayes, A.; Rybalka, E. Mitochondria: Inadvertent targets in chemotherapy-induced skeletal muscle toxicity and wasting? Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2016, 78, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichaya, E.G.; Chiu, G.S.; Krukowski, K.; Lacourt, T.E.; Kavelaars, A.; Dantzer, R.; Heijnen, C.J.; Walker, A.K. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced behavioral toxicities. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.P.; Wang, D.; Kaushal, A.; Saligan, L. Mitochondria-related gene expression changes are associated with fatigue in patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer receiving external beam radiation therapy. Cancer Nurs. 2013, 36, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.P.; Wang, D.; Kaushal, A.; Chen, M.K.; Saligan, L. Differential expression of genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis and bioenergetics in fatigued prostate cancer men receiving external beam radiation therapy. J. Pain. Symptom. Manag. 2014, 48, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.P.; Chen, M.K.; Daly, B.; Hoppel, C. Integrated mitochondrial function and cancer-related fatigue in men with prostate cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 6367–6377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.P.; Chen, M.K.; Veigl, M.L.; Ellis, R.; Cooney, M.; Daly, B.; Hoppel, C. Relationships between expression of BCS1L, mitochondrial bioenergetics, and fatigue among patients with prostate cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 6703–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, J.W.; Chua, P.S.; Ng, T.; Yeo, A.H.L.; Shwe, M.; Gan, Y.X.; Dorajoo, S.; Foo, K.M.; Loh, K.W.; Koo, S.L.; et al. Association of mitochondrial DNA content in peripheral blood with cancer-related fatigue and chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in early-stage breast cancer patients: A prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 168, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filler, K.; Lyon, D.; McCain, N.; Bennett, J., Jr.; Fernandez-Martinez, J.L.; deAndres-Galiana, E.J.; Elswick, R.K., Jr.; Lukkahatai, N.; Saligan, L. Relationship of Mitochondrial Enzymes to Fatigue Intensity in Men with Prostate Cancer Receiving External Beam Radiation Therapy. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2016, 18, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feng, L.R.; Wolff, B.S.; Liwang, J.; Regan, J.M.; Alshawi, S.; Raheem, S.; Saligan, L.N. Cancer-related fatigue during combined treatment of androgen deprivation therapy and radiotherapy is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 45, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleckner, A.S.; Kleckner, I.R.; Culakova, E.; Wojtovich, A.P.; Klinedinst, N.J.; Kerns, S.L.; Hardy, S.J.; Inglis, J.E.; Padula, G.D.A.; Mustian, K.M.; et al. Exploratory analysis of associations between whole blood mitochondrial gene expression and cancer-related fatigue among breast cancer survivors. Nurs. Res. 2022, 71, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina-Campos, M.; Scharping, N.E.; Goldrath, A.W. CD8(+) T cell metabolism in infection and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 718–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenring, E.; Zabel, R.; Bannister, M.; Brown, T.; Findlay, M.; Kiss, N.; Loeliger, J.; Johnstone, C.; Camilleri, B.; Davidson, W.; et al. Updated evidence-based practice guidelines for the nutritional management of patients receiving radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 70, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.L.; Elliott, L.; Fuchs-Tarlovsky, V.; Levin, R.M.; Voss, A.C.; Piemonte, T. Oncology Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline for Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 297–310.e247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.A.; Sullivan, K.R.; Howe, C.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Caan, B.J.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Bandera, E.V.; Wang, Y.; Robien, K.; et al. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 230–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleckner, A.S.; Magnuson, A. The nutritional needs of older cancer survivors. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 13, 738–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Hoffmann, G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.R.; Nguyen, Q.; Ross, A.; Saligan, L.N. Evaluating the Role of Mitochondrial Function in Cancer-related Fatigue. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 135, e57736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics and Clinical Characteristics | All Participants (n = 33) | MedDiet (n = 23) | Usual Care (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 51.0 ± 14.6 | 51.7 ± 14.2 | 49.2 ± 16.3 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 2 (6.1%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0 |

| Female | 31 (93.9%) | 21 (91.3%) | 10 (100%) |

| Race and Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Asian | 2 (6.1%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0 |

| Black/African American | 2 (6.1%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (10%) |

| Hispanic, any race | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 29 (87.9%) | 20 (87.0%) | 9 (90%) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Married or long-term significant other | 25 (75.8%) | 18 (78.3%) | 7 (70%) |

| Divorced, separated, single, or widowed | 8 (24.2%) | 5 (21.7%) | 3 (30%) |

| Employment, n (%) | |||

| Employed (including self-employed) | 20 (60.6%) | 13 (56.5%) | 7 (70%) |

| Homemaker, unemployed, or retired | 13 (39.4%) | 10 (43.5%) | 3 (30%) |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | |||

| Less than a high school degree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| High school/GED | 3 (9.1%) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (20%) |

| 2- or 4-year degree or some college | 16 (48.5%) | 11 (47.8%) | 5 (50%) |

| Graduate degree | 14 (42.4%) | 11 (47.8%) | 3 (30%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 29.4 ± 6.8 | 28.9 ± 6.1 | 30.5 ± 8.5 |

| Type of cancer, n (%) | |||

| Breast | 30 (90.9%) | 20 (87.0%) | 10 (100%) |

| Other | 3 (9.1%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0 |

| Cancer stage, n (%) | |||

| Stage 1 | 8 (24.2%) | 4 (17.4%) | 4 (40%) |

| Stage 2 | 21 (63.6%) | 17 (73.9%) | 4 (40%) |

| Stage 3 | 2 (6.1%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (10%) |

| Other or Unknown | 2 (6.1%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (10%) |

| Previous treatment for cancer, n (%) | |||

| Surgery | 15 (45.5%) | 11 (47.8%) | 4 (40%) |

| Chemotherapy | 1 (3.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0 |

| Radiation | 1 (3.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0 |

| Place in treatment at baseline, n (%) | |||

| Had begun chemotherapy | 25 (76%) | 17 (74%) | 8 (80%) |

| Chemotherapy-naïve | 8 (24%) | 6 (26%) | 2 (20%) |

| Type of chemotherapy, n (%) | |||

| Doxorubicin Cyclophosphamide (AC) * | 11 (33.3%) | 7 (30.4%) | 4 (40%) |

| Paclitaxel (with or without Trastuzumab) | 7 (21.3%) | 4 (17.4%) | 3 (30%) |

| Docetaxel Cyclophosphamide (TC) | 4 (12.1%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (20%) |

| Docetaxel Carboplatin Trastuzumab Pertuzumab (TCHP) | 7 (21.2%) | 6 (26.1%) | 1 (10%) |

| Other (all non-anthracycline) | 4 (12.1%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0 |

| Fatigue Measure | Direct-Ionality | Group | Baseline (Mean ± SD) | Week 4 (Mean ± SD) | Effect Size (95% CI) | Week 8 (Mean ± SD) | Effect Size (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) Total score | Higher is better | Control | 115.4 ± 20.5 | 110.2 ± 26.4 | 0.31 (−0.44–1.06) | 116.9 ± 20.4 | 0.30 (−0.44–1.05) |

| MedDiet | 104.5 ± 28.7 | 107.5 ± 31.9 | 114.1 ± 28.4 | ||||

| FACIT-F: Physical well-being | Higher is better | Control | 20.6 ± 3.9 | 19.1 ± 5.7 | 0.22 (−0.53–0.96) | 20.8 ± 3.9 | 0.18 (−0.56–0.93) |

| MedDiet | 19.5 ± 6.7 | 19.3 ± 6.6 | 20.8 ± 5.9 | ||||

| FACIT-F: Social well-being | Higher is better | Control | 23.8 ± 3.3 | 24.6 ± 2.2 | −0.03 (−0.78–0.71) | 23.3 ± 3.7 | 0.50 (−0.25–1.26) |

| MedDiet | 22.2 ± 2.8 | 22.9 ± 3.4 | 23.2 ± 3.3 | ||||

| FACIT-F: Emotional well-being | Higher is better | Control | 17.8 ± 3.7 | 17.8 ± 4.5 | 0.17 (−0.58–0.91) | 18.8 ± 2.6 | 0.09 (−0.65–0.84) |

| MedDiet | 16.6 ± 4.5 | 17.3 ± 4.0 | 18.0 ± 3.8 | ||||

| FACIT-F: Functional well-being | Higher is better | Control | 17.9 ± 5.9 | 16.8 ± 5.9 | 0.10 (−0.64–0.85) | 18.0 ± 5.6 | 0.03 (−0.71–0.77) |

| MedDiet | 16.5 ± 7.1 | 16.1 ± 7.7 | 16.8 ± 7.1 | ||||

| FACIT-F: Fatigue subscale | Higher is better | Control | 35.3 ± 10.3 | 31.9 ± 12.7 | 0.31 (−0.44–1.06) | 36.0 ± 9.8 | 0.25 (−0.50–0.99) |

| MedDiet | 31.3 ± 14.4 | 32.0 ± 14.2 | 35.3 ± 12.1 | ||||

| FACIT-F: Trial outcome index (fatigue) | Higher is better | Control | 73.8 ± 18.4 | 67.8 ± 23.0 | 0.25 (−0.50–0.99) | 74.8 ± 18.2 | 0.19 (−0.55–0.94) |

| MedDiet | 67.3 ± 26.6 | 67.3 ± 26.9 | 73.0 ± 23.7 | ||||

| FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT)-General | Higher is better | Control | 80.1 ± 11.9 | 78.3 ± 14.8 | 0.22 (−0.52–0.97) | 80.9 ± 11.0 | 0.26 (−0.49–1.00) |

| MedDiet | 74.1 ± 15.8 | 75.6 ± 19 | 78.7 ± 17.1 | ||||

| Brief Fatigue Inventory: Global fatigue score | Lower is better | Control | 2.9 ± 2.4 | 3.3 ± 2.6 | −0.04 (−0.78–0.70) | 2.8 ± 2.2 | −0.32 (−1.07–0.43) |

| MedDiet | 3.4 ± 3.1 | 3.7 ± 2.7 | 2.4 ± 2.3 | ||||

| Brief Fatigue Inventory: Usual fatigue | Lower is better | Control | 3.6 ± 2.7 | 4.0 ± 2.7 | 0.07 (−0.67–0.82) | 2.6 ± 2.0 | 0.04 (−0.71–0.78) |

| MedDiet | 3.4 ± 2.8 | 4.0 ± 3.1 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | ||||

| Brief Fatigue Inventory: Fatigue at its worst | Lower is better | Control | 5.3 ± 2.9 | 5.3 ± 3.7 | 0.15 (−0.59–0.90) | 4.2 ± 3.0 | 0.28 (−0.47–1.02) |

| MedDiet | 4.2 ± 3.4 | 4.7 ± 3.2 | 4.0 ± 3.0 | ||||

| Symptom inventory: Fatigue | Lower is better | Control | 4.3 ± 2.5 | 5.7 ± 3.6 | −0.26 (−1.00–0.49) | 4.0 ± 2.7 | −0.10 (−0.84–0.65) |

| MedDiet | 4.8 ± 3.4 | 5.4 ± 3.2 | 4.2 ± 3.1 | ||||

| Symptom inventory: Sleep problems | Lower is better | Control | 4.0 ± 3.5 | 4.1 ± 3 | 0.03 (−0.71–0.77) | 3.5 ± 2.8 | 0.06 (−0.69–0.80) |

| MedDiet | 3.5 ± 3.7 | 3.7 ± 2.9 | 3.2 ± 2.6 | ||||

| Symptom inventory: Drowsiness | Lower is better | Control | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 4.1 ± 3.1 | −0.10 (−0.85–0.64) | 3.7 ± 2.5 | −0.14 (−0.88–0.61) |

| MedDiet | 4.0 ± 3.2 | 4.0 ± 3.4 | 3.5 ± 2.8 | ||||

| Symptom inventory: Interference of symptoms with quality of life | Lower is better | Control | 2.6 ± 2.3 | 2.5 ± 2.6 | 0.12 (−0.62–0.87) | 1.6 ± 1.9 | −0.22 (−0.96–0.53) |

| MedDiet | 4.0 ± 3.5 | 4.3 ± 3.6 | 2.3 ± 2.1 |

| Fatigue Measure | Basal Respiration (Mean ± SD) | p-Value | Maximal Capacity (Mean ± SD) | p-Value | Spare Capacity (Mean ± SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F): Total score | 23.67 ± 21.12 | 0.272 | 8.80 ± 5.11 | 0.093 | 10.00 ± 6.27 | 0.118 |

| FACIT-F: Physical well-being | 7.14 ± 5.35 | 0.190 | 1.31 ± 1.25 | 0.300 | 1.30 ± 1.49 | 0.386 |

| FACIT-F: Social well-being | −2.69 ± 2.66 | 0.321 | −0.13 ± 0.61 | 0.835 | −0.01 ± 0.73 | 0.988 |

| FACIT-F: Emotional well-being | 0.80 ± 3.35 | 0.813 | −0.07 ± 0.82 | 0.930 | −0.17 ± 0.99 | 0.861 |

| FACIT-F: Functional well-being | 7.97 ± 3.90 | 0.057 | 2.52 ± 0.99 | 0.019 * | 3.13 ± 1.27 | 0.022 * |

|

Functional Assessment of Cancer

Therapy- General (FACT-G) | 12.83 ± 14.14 | 0.375 | 3.37 ± 2.95 | 0.262 | 3.75 ± 3.62 | 0.307 |

| FACIT-F: Fatigue subscale | 20.26 ± 9.63 | 0.044 | 5.60 ± 2.33 | 0.021 * | 6.51 ± 2.87 | 0.029 * |

| Trial Outcome Index | 35.51 ± 18.31 | 0.062 | 9.29 ± 4.45 | 0.044 * | 10.60 ± 5.47 | 0.059 |

| Brief Fatigue Inventory: Total score | −4.49 ± 1.81 | 0.019 * | −0.87 ± 0.51 | 0.096 | −0.79 ± 0.59 | 0.185 |

| Brief Fatigue Inventory: Usual fatigue | −5.91 ± 1.99 | 0.006 * | −1.39 ± 0.53 | 0.014 * | −1.40 ± 0.67 | 0.044 * |

| Brief Fatigue Inventory: Worst fatigue | −4.57 ± 2.58 | 0.086 | −1.11 ± 0.68 | 0.109 | −1.19 ± 0.81 | 0.149 |

| Symptom Inventory: Fatigue | −2.66 ± 2.38 | 0.272 | −0.89 ± 0.57 | 0.129 | −1.08 ± 0.70 | 0.129 |

| Symptom Inventory: Sleep problems | −2.39 ± 3.07 | 0.442 | −0.31 ± 0.70 | 0.666 | −0.25 ± 0.83 | 0.762 |

| Symptom Inventory: Drowsiness | −5.50 ± 2.55 | 0.037 * | −1.06 ± 0.61 | 0.091 | −1.08 ± 0.74 | 0.153 |

| Symptom Inventory: How do symptoms interfere with quality of life? | −4.64 ± 2.44 | 0.067 | −1.14 ± 0.59 | 0.062 | −1.27 ± 0.73 | 0.088 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kleckner, A.S.; Reschke, J.E.; Kleckner, I.R.; Magnuson, A.; Amitrano, A.M.; Culakova, E.; Shayne, M.; Netherby-Winslow, C.S.; Czap, S.; Janelsins, M.C.; et al. The Effects of a Mediterranean Diet Intervention on Cancer-Related Fatigue for Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancers 2022, 14, 4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14174202

Kleckner AS, Reschke JE, Kleckner IR, Magnuson A, Amitrano AM, Culakova E, Shayne M, Netherby-Winslow CS, Czap S, Janelsins MC, et al. The Effects of a Mediterranean Diet Intervention on Cancer-Related Fatigue for Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancers. 2022; 14(17):4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14174202

Chicago/Turabian StyleKleckner, Amber S., Jennifer E. Reschke, Ian R. Kleckner, Allison Magnuson, Andrea M. Amitrano, Eva Culakova, Michelle Shayne, Colleen S. Netherby-Winslow, Susan Czap, Michelle C. Janelsins, and et al. 2022. "The Effects of a Mediterranean Diet Intervention on Cancer-Related Fatigue for Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial" Cancers 14, no. 17: 4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14174202

APA StyleKleckner, A. S., Reschke, J. E., Kleckner, I. R., Magnuson, A., Amitrano, A. M., Culakova, E., Shayne, M., Netherby-Winslow, C. S., Czap, S., Janelsins, M. C., Mustian, K. M., & Peppone, L. J. (2022). The Effects of a Mediterranean Diet Intervention on Cancer-Related Fatigue for Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancers, 14(17), 4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14174202