Medi-Cinema: A Pilot Study on Cinematherapy and Cancer as A New Psychological Approach on 30 Gynecological Oncological Patients

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- a focus on the issues that most frequently emerge in the course of psychological work with oncological gynecology patients;

- the way in which these issues are explored and dealt within the films.

2.1. Participants

- Inclusion criteria:

- Patients affected by gynecological cancer (ovary, cervix, endometrium)

- Aged ≥18 years

- Patients undergoing active oncological treatments (surgery, chemotherapy, maintenance treatments or other)

- Presence at the Oncological Gynecology ward or Female Cancer Day Hospital

- Able to understand and provide informed consent

- Exclusion criteria:

- Patients in comorbidity with other psychiatric pathologies

- Low adherence to care and/or reduced compliance

- Aged >70 years

- Not undergoing oncological treatments

- Inability or unwillingness to provide informed consent

- Patients with preexisting psychopathological disorders

- Patients affected by severe language deficits

- Of the entire enrolled group (30 patients):

- 5 did not complete the test correctly and/or did not participate at the first group meeting: during phone interviews with these patients to determine the reasons/difficulties, we found that 3 had experienced disease progression and felt disinclined to participate in this kind of project, while 2 decided to continue oncological therapy in their respective regions and dropped out.

- 2 patients completed only the T0 test (they died) and were not included in our analysis.

- 23 patients completed just T0 and T1 tests, but not T2 (2 of them died and 2 dropped out after T1 for personal reasons).

- The remaining 19 patients completed T0, T1, and T2.

2.2. Questionnaires

- State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y) [17]: to assess the trait and state anxiety domains.

- General Self Efficacy (GSE) [18]: a self-reporting tool consisting of 10 items, intended to measure self-efficacy. It aims to assess the beliefs a person has about his/her ability to cope with a variety of daily life demands.

- Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) [19,20]: to evaluate psychopathological symptoms. A self-reported, 90-item psychometric tool that objectively evaluates a broad range of symptoms of psychopathology. It measures nine symptom dimensions, i.e., somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism, as well as a class of additional items that assess other aspects. It can provide an overview of a patient’s psychological symptoms and their intensity at a given time point.

- The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [21]: Quality of life questionnaire, specifically tailored for cancer samples. It consists of 30 Likert scale items that satisfy three factors: (1) physical assessment; (2) emotional assessment; and (3) fatigue assessment.

- Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) [22]: to assess the quality of romantic relationships. This tool evaluates the adaptability, quality, and representation that each partner has with regard to an intimate relationship. It is a self-reporting questionnaire consisting of 32 items, divided into four subscales: dyadic satisfaction, dyadic cohesive, dyadic and affective consent.

- Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE-OM) [23,24]: a self-administered questionnaire with 34 items to evaluate the outcome of psychological interventions. Each item refers to the last week and is evaluated on a five-point scale (from never to very often or always). The CORE items refer to four domains: subjective well-being (4 items), symptoms/problems (12 items), functioning (12 items), and risk (6 items).

- Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) [25]: A self-reporting questionnaire used to measure a person’s ability to cope with stressful situations. The assessment of this ability is related to some variables of a psychosocial nature, expressed in items that consider the dispositional and situational aspect that determine reactions to stressful events.

- Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES) [26]: a self-assessment questionnaire consisting of 30-items that measure an individual’s ability to empathize with the emotional experiences of others.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

- (a)

- the sample of all patients who completed the questionnaires at T0 and T1 (23 patients)

- (b)

- the sample of 19 patients who also completed the questionnaires at T2.

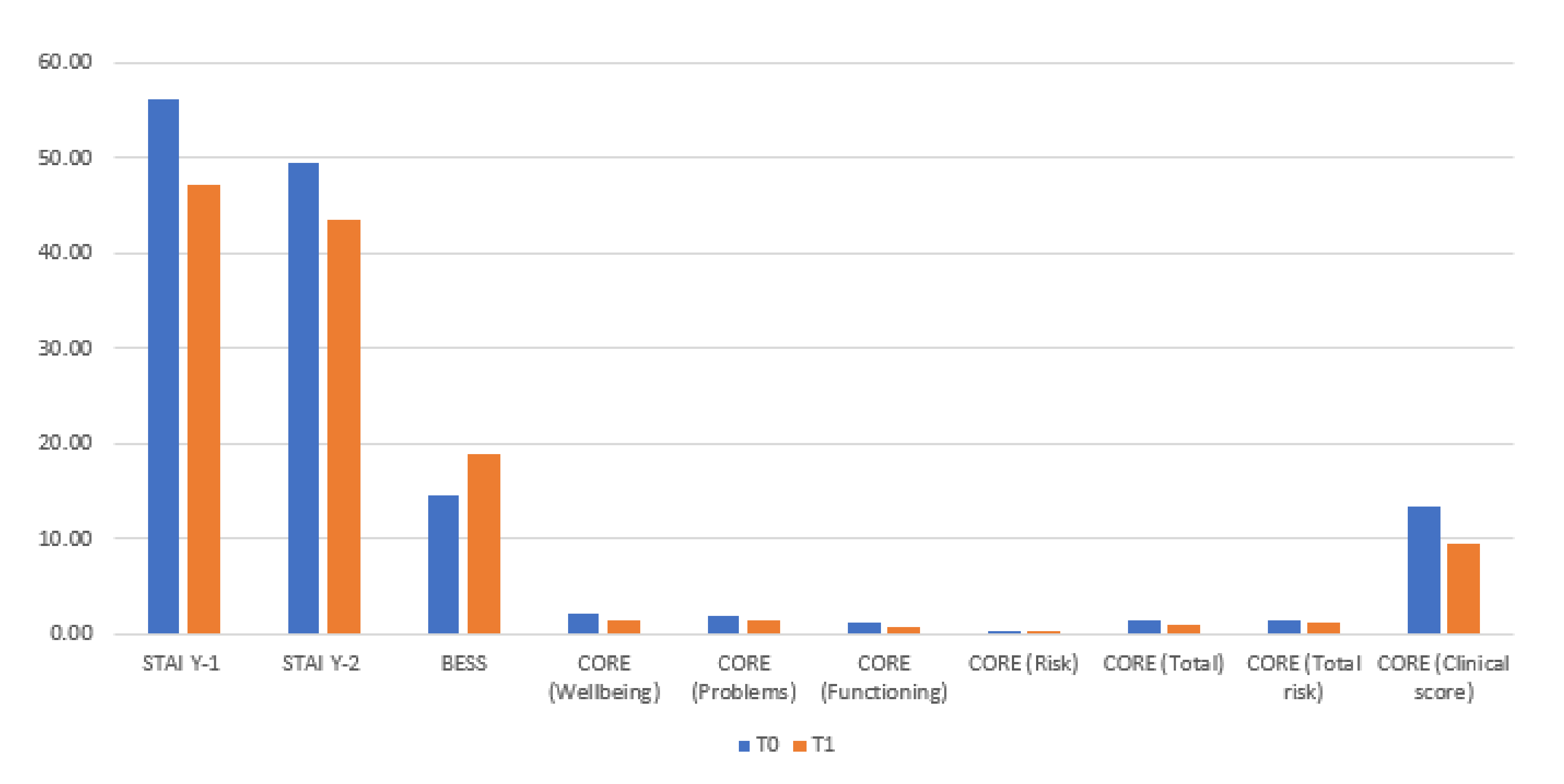

3.1. t-Test with Paired Samples for Time 0 (T0) and Time 1 (T1): Sample of 23 Subjects

3.2. Repeated-Measures ANOVA for Time 0 (T0), Time 1 (T1), and Time (T2): Sample of 19 Subjects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Original Title | Nationality | Year | Issue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intouchables | FR | 2011 | Resources/Adaptability |

| 10 giorni senza mamma | ITA | 2019 | Adaptability/Individual needs |

| Freedom writers | USA | 2007 | Courage/Resilience |

| Wonder | USA | 2017 | Positive attitude/Beyond the disease |

| La famille Bélier | FR | 2014 | Communication/Relationship |

| Inside Out | USA | 2015 | Emotions |

| The Bucket List | USA | 2007 | Time/Death |

| Seven Pounds | USA | 2008 | Change/Opportunity |

| Chocolat | USA | 2000 | Female projects/Prejudice |

| The Theory of Everything | UK | 2014 | Determination/Limits |

| Serendipity | USA | 2001 | Destiny/Trust |

| Love is all you need | USA | 2012 | Shame/Feel guilty |

| TITLE | STORYLINE |

|---|---|

| Intouchables | The film deals with the issue of the psychological consequences of disability. Individuals with a medical condition tend to extend their difficulties to all areas of their life. The film focuses on how an assistant takes care of his client not focusing only on the physical aspects but also, and above all, on his emotional aspects, activating his hidden resources. |

| 10 giorni senza mamma | This is a family comedy where the mother goes on a vacation and leaves the management and organization of the children’s daily life and activities to the father. Between dinners to prepare, kindergarten placement, embarrassing confidences of the oldest daughter, wild games with the son’s friends, quarrels, near disasters, and missed appointments at work, this film highlights the father’s initial disorganization and the subsequent implementation of functional and useful strategies, focusing attention on the ability to delegate (required by many patients in the course of therapies). |

| Freedom writers | This film highlights the courage of teacher Erin Gruwell as she fights for her students, motivating them to engage more and more in their studies. Through writing, he invites her students to explore and share their emotions and thoughts. The aim is not to restore order and discipline, but to seek new balances in a moment of fragility. |

| Wonder | The film stars a child (August) suffering from a rare genetic disease called Treacher Collins Syndrome. The film presents various topics from bullying to the importance of family support, which allows the child to regulate emotional states of sadness, anger, and self-depreciation. At the end of the film, we see how August has attracted the people around him and how diversity and pain are elements of wealth to fight prejudice, prevarication, indifference, and social isolation. |

| La famille Bélier | The film explores profound themes concerning diversity, growth, family life, and the communication of one’s needs. Except for one person, all family members are deaf, and this aspect highlights the inability to assume the perspective of the other. |

| Inside Out | This is an animated film that takes its cue from the theories of Ekman and Plutchick who theorized on primary emotions such as sadness, joy, fear, disgust, anger, and surprise that mixed together give life to secondary emotions such as love, fear, apprehension, etc. At the heart of the film, there is the value of emotions that help individuals understand who they are and why they engage in certain behaviors. All emotions are essential to ensure psychological well-being, they contribute to the formation of the personality. |

| The Bucket List | The film tells the story of two men with terminal cancer who decide to draw up a list of activities to be carried out. Despite the differences between the two protagonists, they agree in making a list of experiences they want to live and share in the time they have available. |

| Seven Pounds | A film that tells the story of an engineer played by Will Smith who causes the death of seven people including his partner, feeling terribly guilty. From that moment on, he totally changes his life and aims to save seven “good people” to alleviate his pain and guilt. |

| Chocolat | The film deals with the arrival of a woman with her child in a village in the French countryside and how they integrate into the small town by opening a small chocolate shop. Shortly after their arrival, the first gossip begins to spread and, consequently, the first prejudices. In the film, the protagonist’s behavior is not one of victimhood but a way to obtain a social redemption provoked by the group. |

| The Theory of Everything | This is a biopic about Stephen Hawking, his professional and personal history. During his illness, the character remains lucid and manages to benefit from the love of his wife and her children. The moment of diagnosis triggers fear and anger in him. At his side is always present his wife Jane, who leaves everything to devote herself completely to him and to take care of the children. |

| Serendipity | It is the love story of two boys who meet in front of a stall and let fate decide their next encounter. Years go by and they are both in the process of getting married until they meet again. The central theme of the film is the relationship between the two protagonists and their way of communicating and welcoming their feelings. |

| Love is all you need | It is the last film that the patients have seen, it is a romantic comedy where the protagonist lets her emotional suffering emerge after her husband leaves her for a younger woman, alternating it with notes of irony. |

Appendix B. Filmography

- Intouchables, Olivier Nakache, Éric Toledano (France, 2011).

- 10 giorni senza mamma, Alessandro Genovesi, Maurizio Totti e Alessandro Usai (Italia, 2019).

- Freedom writers, Richard LaGravenese, (USA, 2007).

- Wonder, Stephen Chbosky, David Hoberman, Todd Lieberman (USA, 2017).

- La famille Bélier, Éric Lartigau, Philippe Rousselet, Éric Jehelmann, Stéphanie Bermann, (France, 2014).

- Inside Out, Pete Docter, Ronnie del Carmen, Jonas Rivera (USA, 2015).

- The Bucket List, Rob Reiner, Alan Greisman, Craig Zadan, Neil Meron, producers, Rob Reiner (USA, 2007).

- Seven Pounds, Gabriele Muccino, Todd Black, Jason Blumenthal, James Lassiter, Will Smith, Steve Tisch (USA, 2008).

- Chocolat, Lasse Hallström, David Brown, Kit Golden, Leslie Holleran (USA, 2000).

- The Theory of Everything, James Marsh, Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Lisa Bruce, Anthony McCarten (USA, 2014).

- Serendipity, Peter Chelsom, Simon Fields, Robert Levy (USA, 2001).

- Love is all you need, Susanne Bier, Sisse Graum Jørgensen, Vibeke Windelov (USA, 2012).

References

- Hood, L.; Friend, S.H. Predictive, personalized, preventive, participatory (P4) cancer medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzarri, N.; Nero, C.; Sillano, F.; Ciccarone, F.; D’Oria, M.; Cesario, A.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Testa, A.C.; Fanfani, F.; Ferrandina, G.; et al. Building a Personalized Medicine Infrastructure for Gynecological Oncology Patients in a High-Volume Hospital. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorini, A.; Pravettoni, G. P5 medicine: A plus for a personalized approach to oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, H.S.; Hartenbach, E.M.; Method, M.W. Patient–provider communication and perceived control for women experiencing multiple symptoms associated with ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 99, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chieff, D.P.R.; Mastrilli, L.; Lafuenti, L.; Costantini, B.; Ferrandina, G.; Salutari, V. The Effectiveness of Psychological Therapy in Patients with Gynecological Cancer. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 6, 1854. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Enns, H.; Woodgate, R. The psychosocial experiences of women with breast cancer across the lifespan: A systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2015, 13, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, G. The Motion Picture Prescription: Watch This Movie and Call Me in the Morning; Aslan Publishing: Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-944031-27-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cinematherapy–Using the Power of Movies for the Therapeutic Process. Available online: https://www.cinematherapy.com/birgitarticles/ctusingpower.html (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Wolz, B. Cinema Therapy. Pridobljeno s Spletnega Mesta. 2013. Available online: http://www.cinematherapy.com (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Ulus, F. Movie Therapy, Moving Therapy; Trafford: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yazici, E.; Ulus, F.; Selvitop, R.; Yazici, A.B.; Aydin, N. Use of movies for group therapy of psychiatric inpatients: Theory and practice. Int. J. Group Psychother. 2014, 64, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermer, S.B.; Hutchings, J.B. Utilizing movies in family therapy: Applications for individuals, couples, and families. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 28, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Il Cinema Cura Davvero: Un Nuovo Servizio ai Pazienti Attraverso L’esperienza del Cinema. Available online: https://www.medicinema-italia.org (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Jeon, K.W. Bibliotherapy for gifted children. Gift. Child Today 1992, 15, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagby, R.M.; Parker, J.D.A.; Taylor, G.J. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994, 38, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressi, C.; Taylor, G.; Parker, J.; Bressi, S.; Brambilla, V.; Aguglia, E.; Allegranti, I.; Bongiorno, A.; Giberti, F.; Bucca, M.; et al. Cross validation of the factor structure of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: An Italian multicenter study. J. Psychosom. Res. 1996, 41, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press Inc.: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R. SCL-90: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual-I for the Revised Version; Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Research Unit: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Sarno, I.; Preti, E.; Prunas, A.; Madeddu, F. SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90-R Adattamento Italiano; Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Cull, A.; Kaasa, S.; Sprangers, M.A. The EORTC modular approach to quality of life assessment in oncology. Int. J. Ment. Health 1994, 23, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanier, G.B. Measuring Dyadic Adjustment: New Scales for Assessing the Quality of Marriage and Symilar Dyads. J. Marriage Fam. 1976, 38, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Mellor-Clark, J.; Margison, F.; Barkham, M.; Audin, K.; Connell, J.; McGrath, G. CORE: Clinical outcomes in routine evaluation. J. Ment. Health 2000, 9, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, G.; Evans, C.; Hansen, V.; Brancaleoni, G.; Ferrari, S.; Porcelli, P.; Rigatelli, M. Validation of the Italian version of the clinical outcomes in routine evaluation outcome measure (CORE—OM). Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2009, 16, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A. Manual for the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES); 1130 Alta Mesa Road: Monterey, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dumtrache, S.D. The effects of a cinema-therapy group on diminishing anxiety in young people. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 127, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Batubara, I.M.S.; Sari, N.Y.; Sari, F.S.; Eagle, M.; Windyastuti, E.; Hapsari, E.; Santoso, J. Cinematherapy-based Group Reminiscence on Older Adults’ Quality of Life. J. Int. Dent. Med. Res. 2021, 14, 1709–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Sacilotto, E.; Salvato, G.; Villa, F.; Salvi, F.; Bottini, G. Through the Looking Glass: A Scoping Review of Cinema and Video Therapy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 732246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G. Effects of a cinema therapy-based group reminiscence program on depression and ego integrity of nursing home elders. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 23, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Testoni, I.; Rossi, E.; Pompele, S.; Malaguti, I.; Orkibi, H. Catharsis Through Cinema: An Italian Qualitative Study on Watching Tragedies to Mitigate the Fear of COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 622174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, A.D.; Hood, L. Systems biology, proteomics, and the future of health care: Toward predictive, preventative, and personalized medicine. J. Proteome Res. 2004, 3, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Entire Group (n = 30) | Sample T0 (n = 23) | Sample T1 (n = 23) | Sample T2 (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age M (DS) | 49.37 | 50.39 | 50.39 | 49.16 |

| (10,152) | (10,782) | (10,782) | (11,032) | |

| Employers N (%) | 22 | 17 | 17 | 13 |

| (73.3%) | (73.9%) | (73.9%) | (68.4%) | |

| Non-employees N (%) | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| (26.7%) | (26.1%) | (26.1%) | (31.6%) |

| Questionnaires | M | DS | t | gl | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAI Y1_State Anxiety | 9.04 | 12.15 | 3.57 | 22.00 | 0.00 |

| STAI Y2_Trait Anxiety | 6.00 | 7.21 | 3.99 | 22.00 | <0.001 |

| BEES | −4.26 | 5.81 | −3.52 | 22.00 | 0.00 |

| EORTC_QLQ-C30 | −4.73 | 17.91 | −1.27 | 22.00 | 0.22 |

| DAS_Dyadic consensus | 0.15 | 1.04 | 0.70 | 22.00 | 0.49 |

| DAS_Dyadic satisfaction | 0.19 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 22.00 | 0.37 |

| DAS_Dyadic cohesion | 0.12 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 22.00 | 0.45 |

| DAS_Affectional expression | 0.19 | 0.89 | 1.01 | 22.00 | 0.32 |

| SELF EFFICACY | 1.57 | 5.44 | 1.38 | 22.00 | 0.18 |

| COPE_Social support | 0.17 | 11.56 | 0.07 | 22.00 | 0.94 |

| COPE_Avoidance strategies | 0.17 | 9.40 | 0.09 | 22.00 | 0.93 |

| COPE_Positive attitude | 0.39 | 12.75 | 0.15 | 22.00 | 0.88 |

| COPE_Problem solving | 0.96 | 11.46 | 0.40 | 22.00 | 0.69 |

| COPE_Turning to religion | −0.78 | 10.26 | −0.37 | 22.00 | 0.72 |

| TAS-20_Difficulty Describing Feelings | −1.00 | 13.36 | −0.36 | 22.00 | 0.72 |

| TAS-20_Difficulty Identifying Feeling | −1.70 | 7.98 | −1.02 | 22.00 | 0.32 |

| TAS-20_Externally-Oriented Thinking | 2.09 | 9.27 | 1.08 | 22.00 | 0.29 |

| CORE_Wellbeing | 0.72 | 0.55 | 6.29 | 22.00 | <0.001 |

| CORE_Problems | 0.58 | 0.80 | 3.50 | 22.00 | 0.00 |

| CORE_Functioning | 0.52 | 0.54 | 4.60 | 22.00 | <0.001 |

| CORE_Risk | 0.15 | 0.30 | 2.40 | 22.00 | 0.03 |

| CORE_Total | 0.40 | 0.38 | 5.05 | 22.00 | <0.001 |

| CORE_Total_Risk | 0.36 | 0.51 | 3.36 | 22.00 | 0.00 |

| CORE_Clinical Score | 3.80 | 3.63 | 5.03 | 22.00 | <0.001 |

| Questionnaires | F | gl | p Value | h2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAI Y1_State anxiety | 23,203 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.563 |

| STAI Y2_Trait Anxiety | 22,964 | 1359–24,463 | <0.001 | 0.561 |

| BEES | 10,586 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.370 |

| EORTC_QLQ-C30 | 4035 | 2–36 | 0.026 | 0.183 |

| DAS_Dyadic consensus | 1000 | 2–10 | 0.402 | 0.167 |

| DAS_Dyadic satisfaction | 4882 | 2–36 | 0.013 | 0.213 |

| DAS_Dyadic cohesion | 7772 | 1530–27,536 | 0.004 | 0.302 |

| DAS_Affectional expression | 1064 | 1021–9185 | 0.330 | 0.106 |

| SELF EFFICACY | 1815 | 2–36 | 0.177 | 0.092 |

| COPE_Social support | 30,180 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.626 |

| COPE_Avoidance strategies | 25,923 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.590 |

| COPE_Positive attitude | 29,294 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.619 |

| COPE_Problem solving | 28,382 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.612 |

| COPE_Turning to religion | 53,867 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.750 |

| TAS-20_Difficulty Describing Feelings | 3050 | 1170–21,063 | 0.060 | 0.145 |

| TAS-20_Difficulty Identifying Feeling | 7226 | 2–36 | 0.002 | 0.286 |

| TAS-20_Externally-Oriented Thinking | 6905 | 2–36 | 0.003 | 0.277 |

| CORE_Wellbeing | 21,327 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.542 |

| CORE_Problems | 8720 | 1291–23,246 | 0.004 | 0.326 |

| CORE_Functioning | 10,987 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.379 |

| CORE_Risk | 16,011 | 1401–25,224 | <0.001 | 0.471 |

| CORE_Total | 19,877 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.525 |

| CORE_Total_Risk | 12,166 | 1460–26,284 | <0.001 | 0.403 |

| CORE_Clinical Score | 14,961 | 2–36 | <0.001 | 0.454 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chieffo, D.P.R.; Lafuenti, L.; Mastrilli, L.; De Paola, R.; Vannuccini, S.; Morra, M.; Salvi, F.; Boškoski, I.; Salutari, V.; Ferrandina, G.; et al. Medi-Cinema: A Pilot Study on Cinematherapy and Cancer as A New Psychological Approach on 30 Gynecological Oncological Patients. Cancers 2022, 14, 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14133067

Chieffo DPR, Lafuenti L, Mastrilli L, De Paola R, Vannuccini S, Morra M, Salvi F, Boškoski I, Salutari V, Ferrandina G, et al. Medi-Cinema: A Pilot Study on Cinematherapy and Cancer as A New Psychological Approach on 30 Gynecological Oncological Patients. Cancers. 2022; 14(13):3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14133067

Chicago/Turabian StyleChieffo, Daniela Pia Rosaria, Letizia Lafuenti, Ludovica Mastrilli, Rebecca De Paola, Sofia Vannuccini, Marina Morra, Fulvia Salvi, Ivo Boškoski, Vanda Salutari, Gabriella Ferrandina, and et al. 2022. "Medi-Cinema: A Pilot Study on Cinematherapy and Cancer as A New Psychological Approach on 30 Gynecological Oncological Patients" Cancers 14, no. 13: 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14133067

APA StyleChieffo, D. P. R., Lafuenti, L., Mastrilli, L., De Paola, R., Vannuccini, S., Morra, M., Salvi, F., Boškoski, I., Salutari, V., Ferrandina, G., & Scambia, G. (2022). Medi-Cinema: A Pilot Study on Cinematherapy and Cancer as A New Psychological Approach on 30 Gynecological Oncological Patients. Cancers, 14(13), 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14133067