Emerging Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

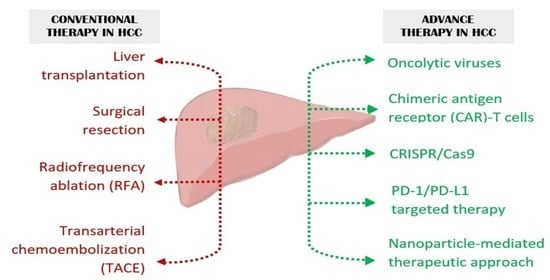

1. Introduction

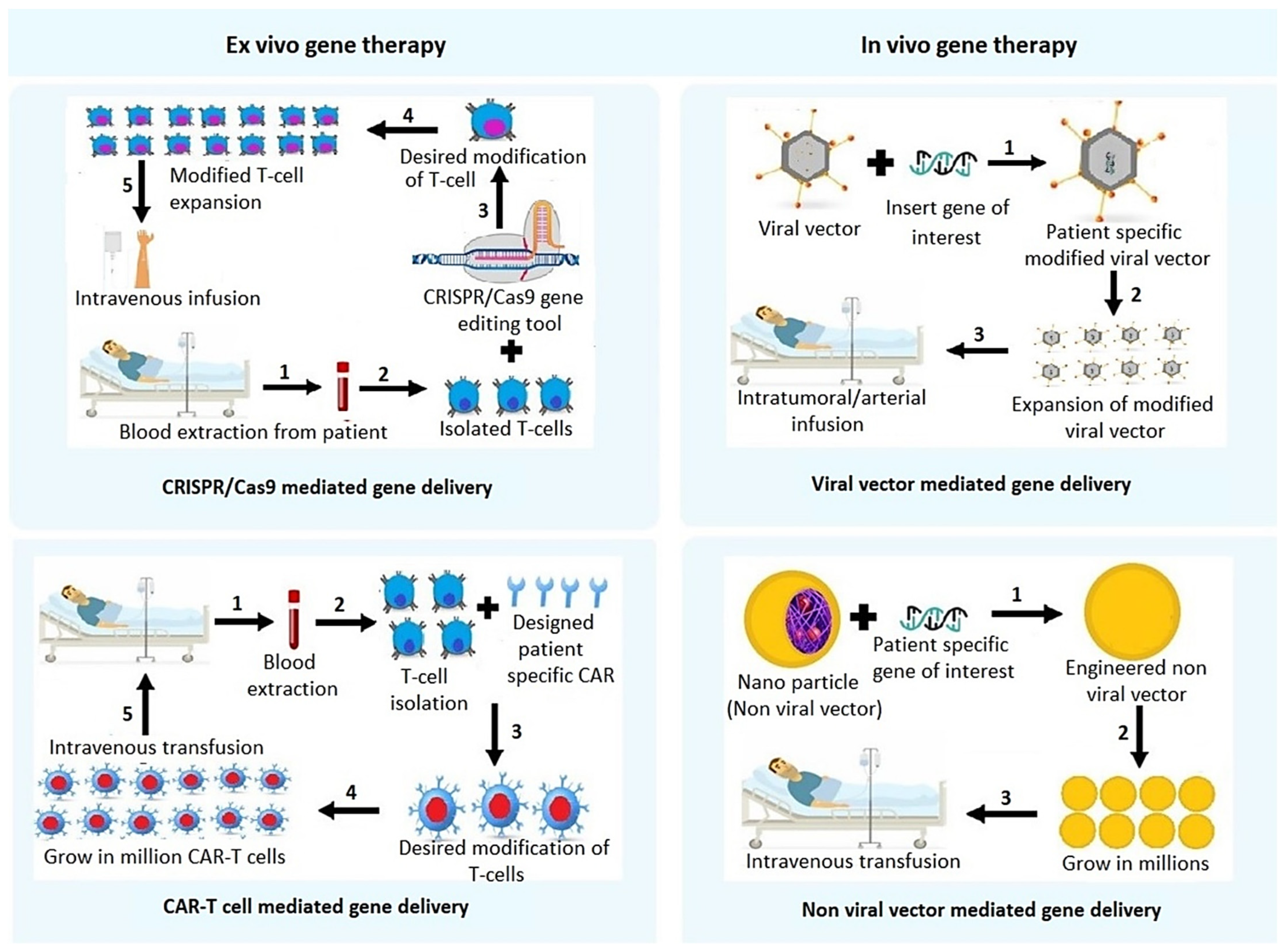

2. Gene Therapy Approaches for HCC

2.1. Non-Viral Vector Mediated Gene Delivery

2.1.1. Biodegradable and Non-Biodegradable Polymer Mediated Gene Delivery

2.1.2. Lipid Based Non-Viral Gene Delivery

2.1.3. Peptide-Based Gene Delivery

2.2. Viral Vector Mediated Gene Therapy Techniques

2.2.1. Adenovirus (AD) and Adeno Associated Virus (AAV)

2.2.2. Lentivirus (LV)

2.2.3. Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)

2.2.4. Vaccinia Virus (VACV)

2.3. Oncolytic Viruses

2.3.1. Oncolytic Ad

2.3.2. Oncolytic VACV

2.3.3. Other Oncolytic Viruses

2.4. Suicide Gene Therapy

2.5. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-Associated Protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9)

3. Immunotherapy Approaches for HCC Treatment

4. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T Cell Therapy

5. Conclusions and Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rinaldi, L.; Guarino, M.; Perrella, A.; Pafundi, P.C.; Valente, G.; Fontanella, L.; Nevola, R.; Guerrera, B.; Iuliano, N.; Imparato, M.; et al. Role of liver stiffness measurement in predicting HCC occurrence in direct-acting antivirals setting: A real-life experience. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 3013–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, L.; Nevola, R.; Franci, G.; Perrella, A.; Corvino, G.; Marrone, A.; Berretta, M.; Morone, M.V.; Galdiero, M.; Giordano, M.; et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after HCV clearance by direct-acting antivirals treatment predictive factors and role of epigenetics. Cancers 2020, 12, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, N.E.; Yopp, A.C.; Singal, A.G.; Murphy, C.C. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence is decreasing among younger adults in the united states. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarchoan, M.; Agarwal, P.; Villanueva, A.; Rao, S.; Dawson, L.A.; Karasic, T.; Llovet, J.M.; Finn, R.S.; Groopman, J.D.; El-Serag, H.B.; et al. Recent developments and therapeutic strategies against hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2019, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medavaram, S.; Zhang, Y. Emerging therapies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.-Y.; Wu, K.-M.; He, X.-X. Advances in drug development for hepatocellular carcinoma: Clinical trials and potential therapeutic targets. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M. The first journal on human gene therapy celebrates its 25th anniversary. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014, 25, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, F.; Lam, M.G.E.H. Delivery approaches of gene therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 4711–4718. [Google Scholar]

- High, K.A.; Roncarolo, M.G. Gene therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Kim, K.-S.; Liu, D. Nonviral gene delivery: What we know and what is next. AAPS J. 2007, 9, E92–E104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, K.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Ge, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Guo, J.; Leng, M.; Wang, P.; et al. Novel hydroxybutyl chitosan nanoparticles for siRNA delivery targeting tissue factor inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 7957–7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, U.; Chauhan, S.; Nagaich, U.; Jain, N. Current advances in chitosan nanoparticles based drug delivery and targeting. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, R.; Wan, J.; Jiang, B.; Zhou, D.; Song, M.; Liu, F. Biological effects of irradiating hepatocellular carcinoma cells by internal exposure with 125i-labeled 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine-chitosan drug loading nanoparticles. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2014, 29, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, H.E.A.; El-Batsh, M.M.; Badawy, N.S.; Mehanna, E.T.; Mesbah, N.M.; Abo-Elmatty, D.M. Ginger extract loaded into chitosan nanoparticles enhances cytotoxicity and reduces cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin in hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 2347–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Huang, H.-L.; Li, J.; Qian, F.-C.; Li, L.-Q.; Niu, P.-P.; Dai, L.-C. Development of hybrid-type modified chitosan derivative nanoparticles for the intracellular delivery of midkine-siRNA in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2015, 14, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chang, R.; Wang, G.; Hu, B.; Qiang, Y.; Chen, Z. Polo-like kinase 1-targeting chitosan nanoparticles suppress the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Q.; Shen, Y.; Liao, M.-M.; Mao, X.; Mi, G.-J.; You, C.; Guo, Q.-Y.; Li, W.-J.; Wang, X.-Y.; Lin, N.; et al. Galactosylated chitosan triptolide nanoparticles for overcoming hepatocellular carcinoma: Enhanced therapeutic efficacy, low toxicity, and validated network regulatory mechanisms. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2019, 15, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.B.; Shah, J.; Al-Dhubiab, B.E.; Patel, S.S.; Morsy, M.A.; Patel, V.; Chavda, V.; Jacob, S.; Sreeharsha, N.; Shinu, P.; et al. Development of asialoglycoprotein receptor-targeted nanoparticles for selective delivery of gemcitabine to hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecules 2019, 24, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.; Nafee, N.; Saad, H.; Kazem, A. Improved antitumor activity and reduced cardiotoxicity of epirubicin using hepatocyte-targeted nanoparticles combined with tocotrienols against hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 88, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.-J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, F.; Guo, Y.-B.; Li, P.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.-F.; Wang, Z.-W.; Yang, Y.-M.; Mao, Q.-S. Asialoglycoprotein receptor-magnetic dual targeting nanoparticles for delivery of RASSF1A to hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.; Yu, X.; Zhuo, H.; Zhou, N.; Xie, Y.; He, J.; Peng, Y.; Xie, X.; Luo, G.; Zhou, S.; et al. Anti-tumor immune response of folate-conjugated chitosan nanoparticles containing the IP-10 gene in mice with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2014, 10, 3576–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.-G.; Liu, L.-P.; Chen, G.G.; Ye, C.G.; Leung, K.K.; Ho, R.L.; Lin, M.C.; Lai, P.B. Therapeutic efficacy of improved α-fetoprotein promoter-mediated tBid delivered by folate-PEI600-cyclodextrin nanopolymer vector in hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 324, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, X.-L.; Zhang, J.-Z.; Mao, X.-H.; Xie, M.-W.; Cheng, Z.-L.; Lu, L.-J.; Duan, X.-H.; Zhang, L.-M.; Shen, J. Magnetic cationic amylose nanoparticles used to deliver survivin-small interfering RNA for gene therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, S.; Tong, L.; Li, J.; Chen, F.; Han, Y.; Zhao, M.; Xiong, W. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles mediated 131I-hVEGF siRNA inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma tumor growth in nude mice. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Kievit, F.M.; Sham, J.G.; Jeon, M.; Stephen, Z.; Bakthavatsalam, A.; Park, J.O.; Zhang, M. Iron-oxide-based nanovector for tumor targeted sirna delivery in an orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma xenograft mouse model. Small 2016, 12, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, Y.; Song, S.J.; Mun, J.Y.; Ko, K.S.; Han, J.; Choi, J.S. Apoptin gene delivery by the functionalized polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer modified with ornithine induces cell death of hepg2 cells. Polymers 2017, 9, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, D.; Srivastava, J.; Ebeid, K.; Gredler, R.; Akiel, M.; Jariwala, N.; Robertson, C.L.; Shen, X.-N.; Siddiq, A.; Fisher, P.B.; et al. Combination of nanoparticle-delivered siRNA for astrocyte elevated gene-1 (aeg-1) and all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA): An effective therapeutic strategy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Bioconjug. Chem. 2015, 26, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, J.; Robertson, C.L.; Ebeid, K.; Dozmorov, M.; Rajasekaran, D.; Mendoza, R.; Siddiq, A.; Akiel, M.A.; Jariwala, N.; Shen, X.-N.; et al. A novel role of astrocyte elevated gene-1 (AEG-1) in regulating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Hepatology 2017, 66, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chhimwal, J.; Patial, V.; Sk, U.H.; Mehak, M.; Mishra, M. Dendrimer-conjugated podophyllotoxin suppresses DENA-induced HCC progression by modulation of inflammatory and fibrogenic factors. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 8, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruvilla, S.P.; Tiruchinapally, G.; Crouch, C.; Elsayed, M.E.H.; Greve, J.M. Dendrimer-doxorubicin conjugates exhibit improved anticancer activity and reduce doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in a murine hepatocellular carcinoma model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, H.J.; Zamboni, C.G.; Radant, N.P.; Bhardwaj, P.; Lechtich, E.R.; Hassan, L.F.; Shah, K.; Green, J.J. Poly(beta-amino ester) nanoparticles enable tumor-specific TRAIL secretion and a bystander effect to treat liver cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2021, 21, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, J.L.; Clares, B.; Morales, M.E.; Gallardo, V.; Ruiz, M.A. Lipid-based drug delivery systems for cancer treatment. Curr. Drug Targets 2011, 12, 1151–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullis, P.R.; Hope, M.J. Lipid nanoparticle systems for enabling gene therapies. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramamoorth, M.; Narvekar, A. Non viral vectors in gene therapy—An overview. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, GE01–GE06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogorad, R.L.; Yin, H.; Zeigerer, A.; Nonaka, H.; Ruda, V.M.; Zerial, M.; Anderson, D.G.; Koteliansky, V. Nanoparticle-formulated siRNA targeting integrins inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma progression in mice. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhr, O.B.; Coelho, T.; Buades, J.; Pouget, J.; Conceicao, I.; Berk, J.; Schmidt, H.; Waddington-Cruz, M.; Campistol, J.M.; Bettencourt, B.R.; et al. Efficacy and safety of patisiran for familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy: A phase II multi-dose study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woitok, M.M.; Zoubek, M.E.; Doleschel, D.; Bartneck, M.; Mohamed, M.R.; Kießling, F.; Lederle, W.; Trautwein, C.; Cubero, F.J. Lipid-encapsulated siRNA for hepatocyte-directed treatment of advanced liver disease. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitamant, J.; Kottakis, F.; Benhamouche, S.; Tian, H.S.; Chuvin, N.; Parachoniak, C.A.; Nagle, J.M.; Perera, R.M.; Lapouge, M.; Deshpande, V.; et al. YAP Inhibition restores hepatocyte differentiation in advanced hcc, leading to tumor regression. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 1692–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.; Swaminathan, S.; Baylot, V.; Mosley, A.; Dhanasekaran, R.; Gabay, M.; Felsher, D.W. Lipid nanoparticles that deliver IL-12 messenger RNA suppress tumorigenesis in MYC oncogene-driven hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzigmann, D.; Grossen, P.; Quintavalle, C.; Lanzafame, M.; Schenk, S.H.; Tran, X.-T.; Englinger, B.; Hauswirth, P.; Grünig, D.; van Schoonhoven, S.; et al. Non-viral gene delivery of the oncotoxic protein NS1 for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Control. Release 2021, 334, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Yin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Pegylated immuno-lipopolyplexes: A novel non-viral gene delivery system for liver cancer therapy. J. Control. Release 2010, 144, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.-W.; Lai, Y.-T.; Chern, G.-J.; Huang, S.-F.; Tsai, C.-L.; Sung, Y.-C.; Chiang, C.-C.; Hwang, P.-B.; Ho, T.-L.; Huang, R.-L.; et al. Galactose derivative-modified nanoparticles for efficient siRNA delivery to hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 2330–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Chern, G.-J.; Hsu, F.-F.; Huang, K.-W.; Sung, Y.-C.; Huang, H.-C.; Qiu, J.T.; Wang, S.-K.; Lin, C.-C.; Wu, C.-H.; et al. A multifunctional nanocarrier for efficient TRAIL-based gene therapy against hepatocellular carcinoma with desmoplasia in mice. Hepatology 2018, 67, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-H.; Yu, B.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Schmidt, C.R.; Lee, R.J.; Lee, L.J.; Jacob, S.T.; Ghoshal, K. Cationic lipid nanoparticles for therapeutic delivery of siRNA and miRNA to murine liver tumor. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2013, 9, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, J.; Shapiro, G.I.; Lorusso, P.M.; Cervantes, A.; Schwartz, G.K.; Weiss, G.J.; Paz-Ares, L.; Cho, D.C.; Infante, J.R.; Alsina, M.; et al. First-in-humans trial of an RNA interference therapeutic targeting VEGF and KSP in cancer patients with liver involvement. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, A.M.; Somaida, A.; Ambreen, G.; Ayoub, A.M.; Tariq, I.; Engelhardt, K.; Garidel, P.; Fawaz, I.; Amin, M.U.; Wojcik, M.; et al. Surface tailored zein as a novel delivery system for hypericin: Application in photodynamic therapy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 129, 112420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sharkawi, F.Z.; Ewais, S.M.; Fahmy, R.H.; Rashed, L.A. PTEN and TRAIL genes loaded zein nanoparticles as potential therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Drug Target. 2017, 25, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-G.; Huang, P.-P.; Zhang, R.; Ma, B.-Y.; Zhou, X.-M.; Sun, Y.-F. Targeting adeno-associated virus and adenoviral gene therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.-C.; Zhou, S.; da Costa, L.T.; Yu, J.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2509–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangro, B.; Mazzolini, G.; Ruiz, M.; Ruiz, J.; Quiroga, J.; Herrero, I.; Qian, C.; Benito, A.; Larrache, J.; Olagüe, C.; et al. A phase I clinical trial of thymidine kinase-based gene therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2010, 17, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, H.; Fuess, S.; Storm, T.A.; Muramatsu, S.; Nara, Y.; Kay, M.A. Unrestricted hepatocyte transduction with adeno-associated virus serotype 8 vectors in mice. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.-C.; Wu, C.-F.; Liao, Y.-J.; Huang, S.-F.; Chen, M.; Chen, Y.-M.A. AAV serotype 8-mediated liver specific GNMT expression delays progression of hepatocellular carcinoma and prevents carbon tetrachloride-induced liver damage. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kota, J.; Chivukula, R.R.; O’Donnell, K.A.; Wentzel, E.A.; Montgomery, C.L.; Hwang, H.-W.; Chang, T.-C.; Vivekanandan, P.; Torbenson, M.; Clark, K.R.; et al. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell 2009, 137, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Urip, B.A.; Zhang, Z.; Ngan, C.C.; Feng, B. Evolving AAV-delivered therapeutics towards ultimate cures. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 99, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escors, D.; Breckpot, K. Lentiviral vectors in gene therapy: Their current status and future potential. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2010, 58, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.A.; Fink, D.J.; Glorioso, J.C. Gene delivery using herpes simplex virus vectors. DNA Cell Biol. 2002, 21, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheust, C.; Goossens, M.; Pauwels, K.; Breyer, D. Biosafety aspects of modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA)-based vectors used for gene therapy or vaccination. Vaccine 2012, 30, 2623–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husseini, F.; Delord, J.-P.; Fournel-Federico, C.; Guitton, J.; Erbs, P.; Homerin, M.; Halluard, C.; Jemming, C.; Orange, C.; Limacher, J.-M.; et al. Vectorized gene therapy of liver tumors: Proof-of-concept of TG4023 (MVA-FCU1) in combination with flucytosine. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marelli, G.; Howells, A.; Lemoine, N.R.; Wang, Y. Oncolytic viral therapy and the immune system: A double-edged sword against cancer. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, J.R.; Kirn, D.H.; Williams, A.; Heise, C.; Horn, S.; Muna, M.; Ng, L.; Nye, J.A.; Sampson-Johannes, A.; Fattaey, A.; et al. An adenovirus mutant that replicates selectively in p53- deficient human tumor cells. Science 1996, 274, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantwill, K.; Klein, F.G.; Wang, D.; Hindupur, S.V.; Ehrenfeld, M.; Holm, P.S.; Nawroth, R. Concepts in oncolytic adenovirus therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbach, C.; Bell, J.C.; Hwang, T.-H.; Kirn, D.; Burke, J. The emerging therapeutic potential of the oncolytic immunotherapeutic Pexa-Vec (JX-594). Oncolytic Virotherapy 2015, 4, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.-H.; Hwang, T.; Liu, T.-C.; Sze, D.Y.; Kim, J.-S.; Kwon, H.-C.; Oh, S.Y.; Han, S.-Y.; Yoon, J.-H.; Hong, S.-H.; et al. Use of a targeted oncolytic poxvirus, JX-594, in patients with refractory primary or metastatic liver cancer: A phase I trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Reid, T.; Ruo, L.; Breitbach, C.J.; Rose, S.; Bloomston, M.; Cho, M.; Lim, H.Y.; Chung, H.C.; Kim, C.W.; et al. Randomized dose-finding clinical trial of oncolytic immunotherapeutic vaccinia JX-594 in liver cancer. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moehler, M.; Heo, J.; Lee, H.; Tak, W.; Chao, Y.; Paik, S.; Yim, H.; Byun, K.; Baron, A.; Ungerechts, G.; et al. Vaccinia-based oncolytic immunotherapy Pexastimogene Devacirepvec in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after sorafenib failure: A randomized multicenter phase IIb trial (TRAVERSE). OncoImmunology 2019, 8, 1615817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhu, W.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, M.X.; Gong, S.; He, S.; Hu, J.; Yan, G.; Liang, J. systematic characterization of the biodistribution of the oncolytic virus M1. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 31, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouljenko, D.; Ding, J.; Lee, I.-F.; Murad, Y.; Bu, X.; Liu, G.; Delwar, Z.; Sun, Y.; Yu, S.; Samudio, I.; et al. induction of durable antitumor response by a novel oncolytic herpesvirus expressing multiple immunomodulatory transgenes. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, S.L. Talimogene laherparepvec: First global approval. Drugs 2016, 76, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.A. Live and let die: A new suicide gene therapy moves to the clinic. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sun, X.; Xing, L.; Deng, X.; Hsiao, H.T.; Manami, A.; Koutcher, J.A.; Ling, C.C.; Li, G.C. Hypoxia targeted bifunctional suicide gene expression enhances radiotherapy in vitro and in vivo. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 105, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lu, X.-X.; Chen, D.-Z.; Li, S.-F.; Zhang, L.-S. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase and ganciclovir suicide gene therapy for human pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aučynaitė, A.; Rutkienė, R.; Tauraitė, D.; Meškys, R.; Urbonavičius, J. Discovery of bacterial deaminases that convert 5-fluoroisocytosine into 5-fluorouracil. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, L.; Shankara, S.; Yoon, S.-K.; Krohne, T.U.; Geissler, M.; Roberts, B.; Blum, H.E.; Wands, J.R. Gene therapy of hepatocellular carcinomain vitro andin vivo in nude mice by adenoviral transfer of theescherichia coli purine nucleoside phosphorylase gene. Hepatology 2000, 31, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Wang, Y.; Gong, L.; Zhu, J.; Gong, R.; Si, J. Suicide gene therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma cells by survivin promoter-driven expression of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 29, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marukawa, Y.; Nakamoto, Y.; Kakinoki, K.; Tsuchiyama, T.; Iida, N.; Kagaya, T.; Sakai, Y.; Naito, M.; Mukaida, N.; Kaneko, S. Membrane-bound form of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 enhances antitumor effects of suicide gene therapy in a model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, K.T.; Lee, S.-J.; Hong, S.-H.; Moon, J.Y.; Yoon, E.K.; Kim, S.; Kim, E.O.; Kang, S.H.; Kim, S.K.; et al. Image-aided suicide gene therapy utilizing multifunctional htert-targeting adenovirus for clinical translation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics 2016, 6, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, K.C.; Huynh, H.T.; Chinnasamy, N.; Hui, K.M.; Lam, P.Y.P. Suicidal gene therapy in the effective control of primary human hepatocellular carcinoma as monitored by noninvasive bioimaging. Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, P.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Tang, L.; Tian, S. Effects of cationic microbubble carrying CD/TK double suicide gene and αVβ3 integrin antibody in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L. An ultrasonic nanobubble-mediated PNP/fludarabine suicide gene system: A new approach for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A.; et al. Multiplex genome engineering using Crispr/Cas systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marraffini, L.A.; Sontheimer, E.J. CRISPR interference: RNA-directed adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, A.; Chevalier, N.; Calderoni, M.; Dubuis, G.; Dormond, O.; Ziros, P.G.; Sykiotis, G.P.; Widmann, C. CRISPR/Cas9 genome-wide screening identifies KEAP1 as a sorafenib, lenvatinib, and regorafenib sensitivity gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 7058–7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.-C.; Luo, B.-Y.; Zou, J.-J.; Wu, P.-Y.; Jiang, J.-L.; Le, J.-Q.; Zhao, R.-R.; Chen, L.; Shao, J.-W. Co-delivery of sorafenib and crispr/cas9 based on targeted core–shell hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles for synergistic HCC therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 57362–57372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.-J.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, N.; Yu, B.; Chen, D.-F.; Yang, M.; Xu, F.-J. Charge-reversal nanocomolexes-based CRISPR/Cas9 delivery system for loss-of-function oncogene editing in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Control. Release 2021, 333, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.S.; Boshra, M.S.; El Meteini, M.S.; Shafei, A.E.-S.; Matboli, M. lncRNA- RP11-156p1.3, novel diagnostic and therapeutic targeting via CRISPR/Cas9 editing in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genomics 2020, 112, 3306–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, M.; Xu, F. A lactose-derived crispr/cas9 delivery system for efficient genome editing in vivo to treat orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendowski, M. The promise of sonodynamic therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Sun, L.; Pu, Y.; Yu, J.; Feng, W.; Dong, C.; Zhou, B.; Du, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Ultrasound-controlled crispr/cas9 system augments sonodynamic therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. ACS Central Sci. 2021, 7, 2049–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, D.G. Immunity, tolerance and autoimmunity in the liver: A comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 2016, 66, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Xu, D.; Liu, Z.; Shi, M.; Zhao, P.; Fu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, C.; et al. Increased regulatory t cells correlate with cd8 t-cell impairment and poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2328–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalathil, S.; Lugade, A.A.; Miller, A.; Iyer, R.; Thanavala, Y. higher frequencies of garp+ctla-4+foxp3+ t regulatory cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients are associated with impaired t-cell functionality. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2435–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.C.; Duffy, C.R.; Allison, J.P. Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1069–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokosuka, T.; Takamatsu, M.; Kobayashi-Imanishi, W.; Hashimoto-Tane, A.; Azuma, M.; Saito, T. Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maker, A.V.; Attia, P.; Rosenberg, S.A. Analysis of the cellular mechanism of antitumor responses and autoimmunity in patients treated with CTLA-4 blockade. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 7746–7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Wang, X.-Y.; Qiu, S.-J.; Yamato, I.; Sho, M.; Nakajima, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, B.-Z.; Shi, Y.-H.; Xiao, Y.-S.; et al. Overexpression of PD-L1 significantly associates with tumor aggressiveness and postoperative recurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sia, D.; Jiao, Y.; Martinez-Quetglas, I.; Kuchuk, O.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; de Moura, M.C.; Putra, J.; Campreciós, G.; Bassaganyas, L.; Akers, N.; et al. Identification of an Immune-specific Class of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Based on Molecular Features. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Castet, F.; Heikenwalder, M.; Maini, M.K.; Mazzaferro, V.; Pinato, D.J.; Pikarsky, E.; Zhu, A.X.; Finn, R.S. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Sangro, B.; Yau, T.; Crocenzi, T.S.; Kudo, M.; Hsu, C.; Kim, T.-Y.; Choo, S.-P.; Trojan, J.; Welling, T.H., 3rd; et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): An open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, T.; Lee, S.S.; Kaseb, A.O. Systemic therapy of liver cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2021, 149, 257–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Ryoo, B.-Y.; Hsu, C.-H.; Numata, K.; Stein, S.; Verret, W.; Hack, S.P.; Spahn, J.; Liu, B.; Abdullah, H.; et al. Atezolizumab with or without bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (GO30140): An open-label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casak, S.J.; Donoghue, M.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.; Jiang, X.; Rodriguez, L.; Shen, Y.-L.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, H.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1836–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Xu, J.; Bai, Y.; Xu, A.; Cang, S.; Du, C.; Li, Q.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; et al. Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): A randomised, open-label, phase 2–3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Ikeda, M.; Zhu, A.X.; Sung, M.W.; Baron, A.D.; Kudo, M.; Okusaka, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Kumada, H.; Kaneko, S.; et al. Phase Ib study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2960–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Nebhan, C.A.; Moslehi, J.J.; Balko, J.M. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: Long-term implications of toxicity. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinkhani, N.; Derakhshani, A.; Kooshkaki, O.; Shadbad, M.A.; Hajiasgharzadeh, K.; Baghbanzadeh, A.; Safarpour, H.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Brunetti, O.; Yue, S.; et al. Immune checkpoints and CAR-T cells: The pioneers in future cancer therapies? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Hao, H.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y. Immunotherapy with CAR-modified T cells: Toxicities and overcoming strategies. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Chen, S.; Lai, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, B.; Lin, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, Q.; Liang, Q.; et al. Anti-GPC3-CAR T cells suppress the growth of tumor cells in patient-derived xenografts of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2017, 7, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochigneux, P.; Chanez, B.; De Rauglaudre, B.; Mitry, E.; Chabannon, C.; Gilabert, M. Adoptive cell therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: Biological rationale and first results in early phase clinical trials. Cancers 2021, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.A.; Yang, J.C.; Kitano, M.; Dudley, M.E.; Laurencot, C.M.; Rosenberg, S.A. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.S.; Lamb, L.S.; Egoldman, F.; Stasi, A.E. Improving the safety of cell therapy products by suicide gene transfer. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whilding, L.; Halim, L.; Draper, B.; Parente-Pereira, A.; Zabinski, T.; Davies, D.; Maher, J. CAR T-Cells Targeting the Integrin αvβ6 and co-expressing the chemokine receptor cxcr2 demonstrate enhanced homing and efficacy against several solid malignancies. Cancers 2019, 11, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisagenlecleucel (kymriah) for all. Med. Lett. Drugs Ther. 2017, 59, 177–178.

- Axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) for B-cell lymphoma. Med. Lett. Drugs Ther. 2018, 60, e122–e123.

- Mullard, A. FDA approves second BCMA-targeted CAR-T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Identifier | Intervention | Phase | Study Status | Entry Routes | Adjuvant | Patients Enrolled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02561546 | rAd-p53 | Phase 2 | Not yet recruiting | Arterial infusion | TAE | Diabetes concurrent with HCC |

| NCT02509169 | rAd-p53 | Phase 2 | Recruiting | Arterial infusion | TAE | Advanced HCC |

| NCT02418988 | rAd-p53 | Phase 2 | Recruiting | Arterial infusion | TACE | Advanced HCC |

| NCT03544723 | Ad-p53 | Phase 2 | Recruiting | Intratumoral injection | anti-PD-1 (ICI) | Solid tumor of HCC |

| NCT00300521 | ADV-Tk | Phase 2 | Completed | N/A | Liver transplant | Advanced HCC |

| NCT03313596 | ADV-Tk | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Peritoneum tissue around the liver | Liver transplant | Advanced HCC |

| NCT02202564 | ADV-Tk | Phase 2 | Completed | Peritoneum injection | Liver transplant | Advanced HCC |

| NCT00844623 | ADV-HSV-TK | Phase 1 | Completed | Intratumoral injection | --- | HCC |

| NCT00669136 | AFP-AdV | Phase 1 | Terminated | Intramuscular | --- | HCC |

| NCT04336241 | HSV-1-RP2 | Phase 1 | Recruiting | Intratumoral injection | --- | HCC |

| NCT00978107 | MVA-FCU1 | Phase 1 | Completed | Intratumoral injection | --- | HCC |

| Study Identifier | Intervention | Adjuvant | Phase | Study Status | Entry Routes | Patients Enrolled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04612504 | SynOV1.1 | atezolizumab | Phase 1 | Not yet recruiting | Intratumoral injection | Patient with AFP positive advanced HCC |

| NCT01869088 | rhAdV type-5 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Arterial infusion | TACE | Unresectable HCC |

| NCT03790059 | rhAdV type-5 | N/A | Recruiting | Intraoperative injection | RFA | HCC |

| NCT05113290 | rhAdV type-5 | Phase 4 | Active, not recruiting | Intratumoral injection | Sorafenib | Advanced HCC |

| NCT00629759 | JX-594 (Pexa-Vec) | --- | Phase 1 | completed | Transdermal injection | patients with advanced HCC |

| NCT00554372 | JX-594 (Pexa-Vec) | --- | Phase 2 | Completed | Intratumoral injection | Unresectable primary HCC |

| NCT02562755 | Pexa-Vec (JX-594) | Sorafenib | Phase 3 | Completed | Intratumoral injection | HCC patients |

| NCT01387555 | JX-594 (Pexa-Vec) | --- | Phase 2 | Completed | N/A | patients with advanced HCC |

| NCT03071094 | Pexa-Vec (JX-594) | Nivolumab | Phase 1 | Terminated | Intratumoral injection | patients with advanced HCC |

| NCT05061537 | PF-07263689 | Sasanlimab | Phase 1 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | metastatic solid tumors with HCC |

| NCT04665362 | M1 (M1-c6v1) | Apatinib | Phase 1 | Not yet recruiting | Intravenous infusion | patients with advanced HCC |

| NCT05223816 | VG161 | --- | Phase 2 | Not yet recruiting | Intratumoral injection | HCC patients |

| Study Identifier | Intervention | Target | Phase | Study Status | Entry Routes | Patients Enrolled (Enrolment Target) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04294498 | Durvalumab | PD-1 | Phase 2 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | HCC patients with active chronic HBV infection (43) |

| NCT04268888 (TACE-3) | Nivolumab | PD-1 | Phase 2/3 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Intermediate stage HCC all receiving TACE/TAE and half receiving nivolumab (522) |

| NCT02576509 | Nivolumab | PD-1 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | First line treatment with advanced HCC patient; compares efficacy versus sorafenib treatment (743: 371 nivolumab; 372 sorafenib) |

| NCT03412773 (RATIONALE-301) | Tislelizumab | PD-1 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Patients with unresectable HCC; compares efficacy versus sorafenib treatment (674) |

| NCT0270241MK-3475-224/KEYNOTE-224) | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Phase 2 | Active, Not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Advanced HCC patients (156) |

| NCT03062358 (MK-3475-394/KEYNOTE-394) | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Advanced HCC patients; compared to placebo given with best supportive care (454) |

| NCT03867084 (KEYNOTE-937) | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | As adjuvant therapy in HCC patients with complete radiological response after surgical resection or local ablation; compared to placebo (950) |

| NCT03383458 (CheckMate 9DX) | Nivolumab | PD-1 | Phase 3 | Active, Not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | As adjuvant therapy in HCC patients with complete surgical resection or complete response after local ablation; compared to placebo (545) |

| NCT03859128 (JUPITER 04) | Toripalimab | PD-1 | Phase 2/3 | Active, Not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | As adjuvant therapy in HCC patients with complete surgical resection; compared to placebo (402) |

| Study Identifier | Intervention | Target | Phase | Study Status | Entry Routes | Patients Enrolled (Enrolment Target) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04712643 | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | PD-L1, VEGF | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Untreated HCC patients; compares with TACE alone or TACE with combination therapy (342) |

| NCT04803994 | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | PD-L1, VEGF | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Intermediate stage HCC patients; compares with TACE alone or TACE with combination therapy (434) |

| NCT04102098 (IMbrave050) | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | PD-L1, VEGF | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Patients with completely resected or ablated HCC who are at high risk of disease recurrence; compares with active surveillance (668) |

| NCT03434379 (IMbrave150) | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | PD-L1, VEGF | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Untreated locally advanced HCC; compares efficacy versus sorafenib treatment (336 immunotherapy; 165 sorafenib) |

| NCT04770896 (IMbrave251) | Atezolizumab + Lenvatinib or Sorafenib | PD-L1, TKI | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Unresectable HCC; compares efficacy or combination versus lenvatinib or sorafenib (554) |

| NCT04039607 (CheckMate 9DW) | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | PD-1, CTLA-4 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Advanced HCC; compares efficacy versus sorafenib or lenvatinib treatment (728) |

| NCT03006926 | Lenvatinib + Pembrolizumab | TKI, PD-1 | Phase 1 | Active, not recruiting | Capsule & IV respectively | Patients with HCC (104) |

| NCT05027425 | Durvalumab + Tremelimumab | PD-1, CTLA-4 | Phase 2 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Patient listed for liver transplant (30) |

| NCT04340193 (CheckMate 74W) | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | PD-1, CTLA-4 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Patients with intermediate HCC (40) |

| NCT03510871 | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | PD-1, CTLA-4 | Phase 2 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Patients with HCC; compares TACE with nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab (26) |

| NCT03755791 (COSMIC-312) | Cabozantinib + Atezolizumab | TKI, PD-L1 | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Oral & IV infusion respectively | Advanced HCC, not received previous systemic therapy; compares efficacy versus sorafenib (370 combination treatment; 185 sorafenib; 185 cabozanitinib monotherapy) |

| NCT04246177(MK-7902-012/E7080- G000-318/LEAP-012) | Lenvatinib + Pembrolizumab | TKI, PD-1 | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Oral & IV infusion respectively | Incurable, non-metastatic HCC patients; compares efficacy of TACE with or without combination therapy (950) |

| NCT04777851 (RENOTACE) | Regorafenib + Nivolumab | TKI, PD-1 | Phase 3 | Not yet recruiting | Oral and IV, respectively | Intermediate stage HCC; compares TACE with combination therapy (496) |

| NCT03970616 (DEDUCTIVE) | Durvalumab + Tivozanib | PD-1, VEGF | Phase2/1 | Recruiting | IV & oral respectively | Advance HCC patients (42) |

| NCT05312216 | Lenvatinib + Durvalumab | TKI, PD-1 | Phase 2 | Not yet recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Unresectable HCC patients (25) |

| NCT04720716 | Sintilimab + IBI310 | PD-1, VEGF | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | First line treatment for advanced HCC; compares efficacy versus sorafenib (490) |

| NCT03794440 | Sintilimab + IBI305 | PD-1, VEGF | Phase 2/3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | First line treatment for advanced HCC; compares efficacy versus sorafenib (595) |

| NCT04465734 | HLX10 + HLX04 | PD-1, VEGF | Phase 3 | Not yet recruiting | Intravenous infusion | First line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic HCC; compares efficacy versus sorafenib (477) |

| NCT04344158 | AK105 + Anlotinib | PD-1, VEGF | Phase 3 | Not yet recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Advanced HCC; compares efficacy versus sorafenib (648) |

| NCT04560894 | SCI-I10A + SCT510 | PD-1, VEGF | Phase 2/3 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Advanced HCC; compares efficacy versus sorafenib (621) |

| NCT03298451 (HIMALAYA) | Durvalumab + Tremelimumab | PD-1, CTLA-4 | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Advance HCC patients; compares efficacy versus sorafenib or durvalumab monotherapy (1504) |

| NCT03778957 (EMERALD-1) | Durvalumab+ bevacizumab | PD-1, VEGF | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Locoregional HCC not amenable to curative therapy; compares efficacy of TACE with durvalumab monotherapy or combination therapy (724) |

| NCT03847428 (EMERALD-2) | Durvalumab + bevacizumab | PD-1, VEGF | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Intravenous infusion | High-risk of recurrence HCC after curative resection or ablation; compares efficacy with durvalumab monotherapy (888) |

| NCT02519348 | Durvalumab + tremelimumab/durvalumab + bevacizumab | PD-1, CTLA-4, VEGF | Phase 2 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous infusion | Advanced HCC patients; compares efficacy with durvalumab or tremelimumab monotherapy (433) |

| Study identifier | Intervention | Target | Phase | Study status | Entry routes | Patients enrolled (enrolment target) |

| NCT04682210 (DaDaLi) | Sintilimab + apatinib | PD1, TKI | Phase 3 | Not yet recruiting | Intravenous | HCC patients with high risk of recurrence after resection (246) |

| NCT03764293 | SHR-1210 + apatinib | PD1, TKI | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Intravenous & oral, respectively | Locally advanced or metastatic and unresectable HCC patients; compares efficacy of combination versus sorafenib (543) |

| NCT04194775 | CS1003 + lenvatinib | PD1, TKI | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Intravenous | Advanced HCC patients not eligible for locoregional therapy; compares efficacy of combination versus lenvatinib (525) |

| NCT03605706 | SHR-1210 + FOLFOX4 | PD1, chemotherapy | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Intravenous | Advanced HCC patients; compares efficacy of combination versus FOLFOX4 (396) |

| NCT04639180 | Camrelizumab + apatinib | PD1, TKI, | Phase 3 | Recruiting | Intravenous & oral, respectively | HCC patients with high risk of recurrence after resection or ablation (674) |

| Study Identifier | Intervention | Phase | Study Status | Entry Routes | Patients Enrolled (Number of Patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04121273 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | Intravenous (IV) Infusion | GPC3 positive advanced HCC patients (20) |

| NCT03980288 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Completed | IV infusion | HCC patients (6) |

| NCT03146234 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Completed | IV infusion | Patients with relapse or refractory HCC (7) |

| NCT05003895 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | IV infusion | Advance GPC3 expressing HCC patients (38) |

| NCT05155189 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | IV infusion | Advance HCC patient (20) |

| NCT02395250 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Completed | IV infusion | Advance HCC patient (13) |

| NCT03884751 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Completed | IV infusion | Advanced HCC patients (9) |

| NCT05070156 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | IV infusion | GPC3 positive advanced HCC patients (3) |

| NCT02905188 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Active, not recruiting | IV infusion | HCC patient (9) |

| NCT03198546 | GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | IV infusion | HCC with GPC3 expression (30) |

| NCT05103631 | IL-15+GPC3-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | IV infusion | GPC3-positive solid HCC tumor (27) |

| NCT03993743 | CD147-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | Hepatic artery infusion | Very advanced HCC (34) |

| NCT03349255 | Anti-HLA-A02/AFP-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Terminated | IV infusion | AFP expressing HCC patients (3) |

| NCT03013712 | EPCAM-CAR-T | Phase 1/2 | Unknown | IV infusion | Advanced HCC (60) |

| NCT02729493 | EPCAM-CAR-T | Phase 2 | Unknown | IV infusion | Advanced HCC (25) |

| NCT05028933 | EPCAM-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | IV infusion | Advanced HCC (48) |

| NCT02587689 | Anti-MUC1 CAR-T | Phase 1/2 | Unknown | IV infusion | Patients with MUC1 + advanced refractory solid tumor (20) |

| NCT05323201 | B7H3 CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | Transhepatic arterial infusion | Advanced B7H3-positive HCC (15) |

| NCT05131763 | NKG2D-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Recruiting | Hepatic portal artery injection | Patients with NKG2DL + solid tumor (3) |

| NCT04550663 | NKG2D-CAR-T | Phase 1 | Not yet recruiting | IV infusion | Relapsed or refractory NKG2DL + tumor (10) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chakraborty, E.; Sarkar, D. Emerging Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). Cancers 2022, 14, 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14112798

Chakraborty E, Sarkar D. Emerging Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). Cancers. 2022; 14(11):2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14112798

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakraborty, Eesha, and Devanand Sarkar. 2022. "Emerging Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)" Cancers 14, no. 11: 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14112798

APA StyleChakraborty, E., & Sarkar, D. (2022). Emerging Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). Cancers, 14(11), 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14112798