HSV-1 Oncolytic Viruses from Bench to Bedside: An Overview of Current Clinical Trials

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

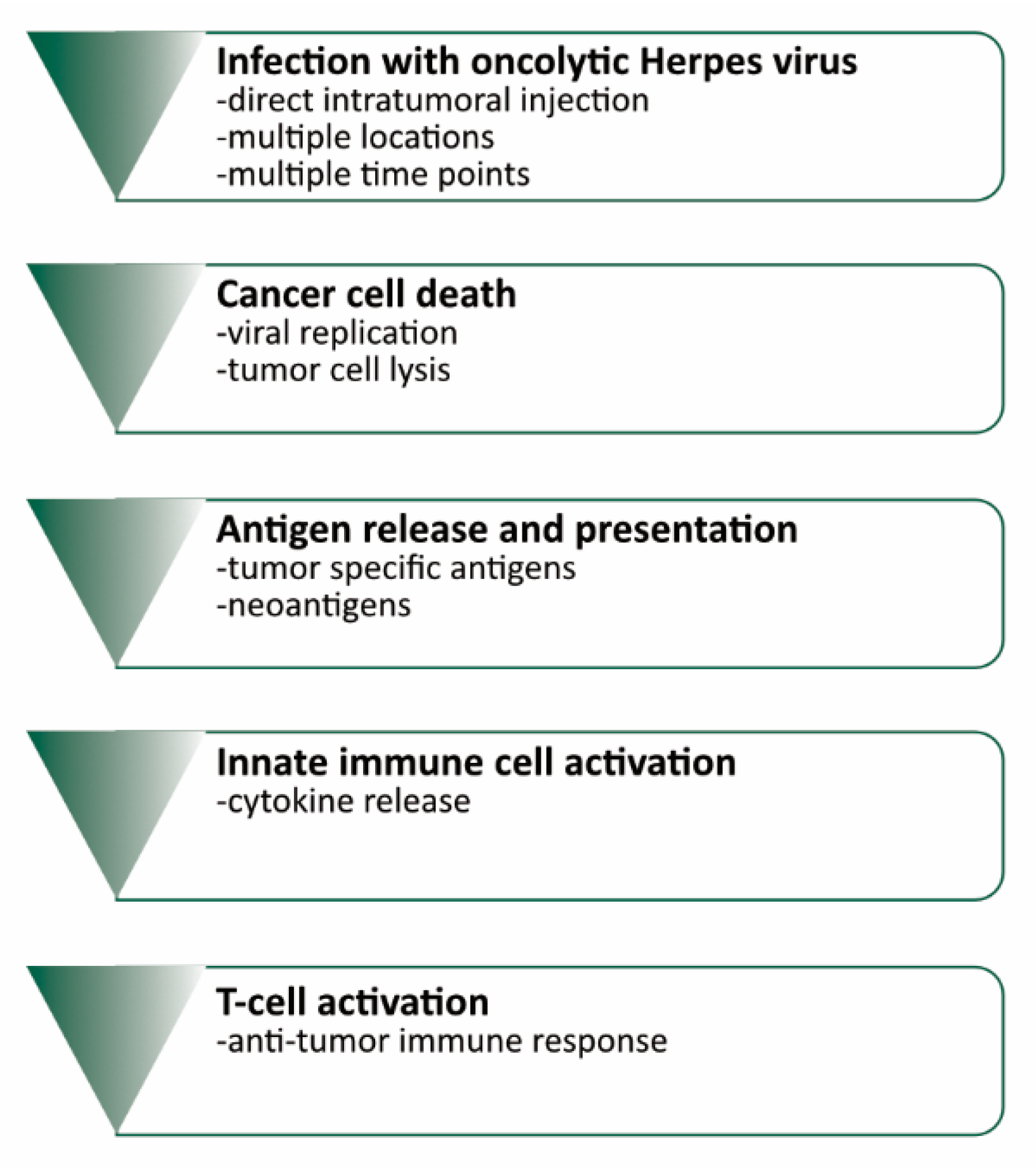

1. Introduction

2. HSV-1-Derived Oncolytic Viruses in Clinical Trials

2.1. HSV-1716

2.2. G207

2.3. HF10

2.4. NV1020

2.5. Talimogene Laherparepvec

3. Future Directions for Next Generation oHSVs

3.1. G47Δ

3.2. rQNestin34.5

3.3. M032

3.4. ONCR-177

3.5. C134

3.6. RP1/2

3.7. Rrp450

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phan, G.Q.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Hwu, P.; Topalian, S.L.; Schwartzentruber, D.J.; Restifo, N.P.; Haworth, L.R.; Seipp, C.A.; Freezer, L.J.; et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8372–8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Tykodi, S.S.; Chow, L.Q.M.; Hwu, W.J.; Topalian, S.L.; Hwu, P.; Drake, C.G.; Camacho, L.H.; Kauh, J.; Odunsi, K.; et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2455–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; Gettinger, S.N.; Smith, D.C.; McDermott, D.F.; Powderly, J.D.; Carvajal, R.D.; Sosman, J.A.; Atkins, M.B.; et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.E.; Alizadeh, D.; Starr, R.; Weng, L.; Wagner, J.R.; Naranjo, A.; Ostberg, J.R.; Blanchard, M.S.; Kilpatrick, J.; Simpson, J.; et al. Regression of glioblastoma after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2561–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.A.; Shi, V.; Maric, I.; Wang, M.; Stroncek, D.F.; Rose, J.J.; Brudno, J.N.; Stetler-Stevenson, M.; Feldman, S.A.; Hansen, B.G.; et al. T cells expressing an anti-B-cell maturation antigen chimeric antigen receptor cause remissions of multiple myeloma. Blood 2016, 128, 1688–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, L.A.; Manzanera, A.G.; Bell, S.D.; Cavaliere, R.; McGregor, J.M.; Grecula, J.C.; Newton, H.B.; Lo, S.S.; Badie, B.; Portnow, J.; et al. Phase II multicenter study of gene-mediated cytotoxic immunotherapy as adjuvant to surgical resection for newly diagnosed malignant glioma. Neuro. Oncol. 2016, 18, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilf, N.; Kuttruff-Coqui, S.; Frenzel, K.; Bukur, V.; Stevanović, S.; Gouttefangeas, C.; Platten, M.; Tabatabai, G.; Dutoit, V.; van der Burg, S.H.; et al. Actively personalized vaccination trial for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Nature 2019, 565, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, S.E.; Speranza, M.C.; Cho, C.F.; Chiocca, E.A. Oncolytic viruses in cancer treatment a review. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristensson, K. Morphological studies of the neural spread of herpes simplex virus to the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 1970, 16, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studahl, M.; Cinque, P.; Bergström, T. Herpes Simplex Viruses; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780849355806. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G.; Xu, W.; Reed, A.; Babra, B.; Putman, T.; Wick, E.; Wechsler, S.L.; Rohrmann, G.F.; Jin, L. Sequence and comparative analysis of the genome of HSV-1 strain McKrae. Virology 2012, 433, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, W.; He, H.; Wang, H. Oncolytic herpes simplex virus and immunotherapy. BMC Immunol. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Kaufman, H.L.; Collichio, F.; Amatruda, T.; Senzer, N.; Chesney, J.; Delman, K.A.; Spitler, L.E.; Puzanov, I.; Agarwala, S.S.; et al. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2780–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, D.J.; Weller, S.K. Herpes simplex virus type 1-induced ribonucleotide reductase activity is dispensable for virus growth and DNA synthesis: Isolation and characterization of an ICP6 lacZ insertion mutant. J. Virol. 1988, 62, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacLean, A.R.; Ul-Fareed, M.; Robertson, L.; Harland, J.; Brown, S.M. Herpes simplex virus type 1 deletion variants 1714 and 1716 pinpont neurovirulence-related sequences in Glasgow strain 17+ between immediate early gene 1 and the “a” sequence. J. Gen. Virol. 1991, 72, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takakuwa, H.; Goshima, F.; Nozawa, N.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kimata, H.; Nakao, A.; Nawa, A.; Kurata, T.; Sata, T.; Nishiyama, Y. Oncolytic viral therapy using a spontaneously generated herpes simplex virus type 1 variant for disseminated peritoneal tumor in immunocompetent mice. Arch. Virol. 2003, 148, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, I.R.; Naoe, Y.; Bustos-Villalobos, I.; Ichinose, T.; Tanaka, M.; Zhiwen, W.; Mukoyama, N.; Morimoto, T.; Miyajima, N.; Hitoki, H.; et al. Genomic signature of the natural oncolytic herpes simplex virus HF10 and its therapeutic role in preclinical and clinical trials. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.J.; Wong, J.; Fong, Y. Herpes simplex virus NV1020 as a novel and promising therapy for hepatic malignancy. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2008, 17, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.L.; Robinson, M.; Han, Z.Q.; Branston, R.H.; English, C.; Reay, P.; McGrath, Y.; Thomas, S.K.; Thornton, M.; Bullock, P.; et al. ICP34.5 deleted herpes simplex virus with enhanced oncolytic, immune stimulating, and anti-tumour properties. Gene Ther. 2003, 10, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Streby, K.A.; Currier, M.A.; Triplet, M.; Ott, K.; Dishman, D.J.; Vaughan, M.R.; Ranalli, M.A.; Setty, B.; Skeens, M.A.; Whiteside, S.; et al. First-in-Human Intravenous Seprehvir in Young Cancer Patients: A Phase 1 Clinical Trial. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1930–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rampling, R.; Cruickshank, G.; Papanastassiou, V.; Nicoll, J.; Hadley, D.; Brennan, D.; Petty, R.; MacLean, A.; Harland, J.; McKie, E.; et al. Toxicity evaluation of replication-competent herpes simplex virus (ICP 34.5 null mutant 1716) in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. Gene Ther. 2000, 7, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mackie, R.M.; Stewart, B.; Brown, S.M. Intralesional injection of herpes simplex virus 1716 in metastatic melanoma. Lancet 2001, 357, 525–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineta, T.; Rabkin, S.D.; Yazaki, T.; Hunter, W.D.; Martuza, R.L. Attenuated multi-mutated herpes simplex virus-1 for the treatment of malignant gliomas. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markert, J.M.; Medlock, M.D.; Rabkin, S.D.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Todo, T.; Hunter, W.D.; Palmer, C.A.; Feigenbaum, F.; Tornatore, C.; Tufaro, F.; et al. Conditionally replicating herpes simplex virus mutant G207 for the treatment of malignant glioma: Results of a phase I trial. Gene Ther. 2000, 7, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Markert, J.M.; Liechty, P.G.; Wang, W.; Gaston, S.; Braz, E.; Karrasch, M.; Nabors, L.B.; Markiewicz, M.; Lakeman, A.D.; Palmer, C.A.; et al. Phase Ib trial of mutant herpes simplex virus G207 inoculated pre-and post-tumor resection for recurrent GBM. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markert, J.M.; Razdan, S.N.; Kuo, H.C.; Cantor, A.; Knoll, A.; Karrasch, M.; Nabors, L.B.; Markiewicz, M.; Agee, B.S.; Coleman, J.M.; et al. A phase 1 trial of oncolytic HSV-1, g207, given in combination with radiation for recurrent GBM demonstrates safety and radiographic responses. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Umene, K.; Eto, T.; Mori, R.; Takagi, Y.; Enquist, L.W. Herpes simplex virus type 1 restriction fragment polymorphism determined using southern hybridization. Arch. Virol. 1984, 80, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Kimura, H.; Daikoku, T. Complementary lethal invasion of the central nervous system by nonneuroinvasive herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 4520–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakao, A.; Kimata, H.; Imai, T.; Kikumori, T.; Teshigahara, O. Intratumoral injection of herpes simplex virus HF10 in recurrent breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 987–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimata, H.; Imai, T.; Kikumori, T.; Teshigahara, O.; Nagasaka, T.; Goshima, F.; Nishiyama, Y.; Nakao, A. Pilot study of oncolytic viral therapy using mutant herpes simplex virus (HF10) against recurrent metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 13, 1078–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, A.; Kasuya, H.; Sahin, T.T.; Nomura, N.; Kanzaki, A.; Misawa, M.; Shirota, T.; Yamada, S.; Fujii, T.; Sugimoto, H.; et al. A phase I dose-escalation clinical trial of intraoperative direct intratumoral injection of HF10 oncolytic virus in non-resectable patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2011, 18, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirooka, Y.; Kasuya, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Kawashima, H.; Ohno, E.; Villalobos, I.B.; Naoe, Y.; Ichinose, T.; Koyama, N.; Tanaka, M.; et al. A Phase I clinical trial of EUS-guided intratumoral injection of the oncolytic virus, HF10 for unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Mizuno, T.; Sugiura, S.; Goshima, F.; Kohno, S.I.; Nakashima, T.; Nishiyama, Y. Intratumoral injection of herpes simplex virus HF10 in recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006, 126, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebright, M.I.; Zager, J.S.; Malhotra, S.; Delman, K.A.; Weigel, T.L.; Rusch, V.W.; Fong, Y. Replication-competent herpes virus NV1020 as direct treatment of pleural cancer in a rat model. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002, 124, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wong, R.J.; Kim, S.H.; Joe, J.K.; Shah, J.P.; Johnson, P.A.; Fong, Y. Effective treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by an oncolytic herpes simplex virus. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2001, 193, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.J.; Delman, K.A.; Burt, B.M.; Mariotti, A.; Malhotra, S.; Zager, J.; Petrowsky, H.; Mastorides, S.; Federoff, H.; Fong, Y. Comparison of safety, delivery, and efficacy of two oncolytic herpes viruses (G207 and NV1020) for peritoneal cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002, 9, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gutermann, A.; Mayer, E.; Von Dehn-Rothfelser, K.; Breidenstein, C.; Weber, M.; Muench, M.; Gungor, D.; Suehnel, J.; Moebius, U.; Lechmann, M. Efficacy of oncolytic herpesvirus NV1020 can be enhanced by combination with chemotherapeutics in colon carcinoma cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006, 17, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny, N.; Brown, K.; Covey, A.; Kim, T.; Bhargava, A.; Brody, L.; Guilfoyle, B.; Haag, N.P.; Karrasch, M.; Glasschroeder, B.; et al. Phase I, open-label, dose-escalating study of a genetically engineered herpes simplex virus, NV1020, in subjects with metastatic colorectal carcinoma to the liver. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006, 17, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Y.; Kim, T.; Bhargava, A.; Schwartz, L.; Brown, K.; Brody, L.; Covey, A.; Karrasch, M.; Getrajdman, G.; Mescheder, A.; et al. A herpes oncolytic virus can be delivered via the vasculature to produce biologic changes in human colorectal cancer. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geevarghese, S.K.; Geller, D.A.; De Haan, H.A.; Hörer, M.; Knoll, A.E.; Mescheder, A.; Nemunaitis, J.; Reid, T.R.; Sze, D.Y.; Tanabe, K.K.; et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic herpes simplex virus NV1020 in patients with extensively pretreated refractory colorectal cancer metastatic to the liver. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010, 21, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, J.C.C.; Coffin, R.S.; Davis, C.J.; Graham, N.J.; Groves, N.; Guest, P.J.; Harrington, K.J.; James, N.D.; Love, C.A.; McNeish, I.; et al. A phase I study of OncoVEXGM-CSF, a second-generation oncolytic herpes simplex virus expressing granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 6737–6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Senzer, N.N.; Kaufman, H.L.; Amatruda, T.; Nemunaitis, M.; Reid, T.; Daniels, G.; Gonzalez, R.; Glaspy, J.; Whitman, E.; Harrington, K.; et al. Phase II clinical trial of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-encoding, second-generation oncolytic herpesvirus in patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5763–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, H.L.; Kim, D.W.; Deraffele, G.; Mitcham, J.; Coffin, R.S.; Kim-Schulze, S. Local and distant immunity induced by intralesional vaccination with an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF in patients with stage IIIc and IV melanoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 17, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Ross, M.; Puzanov, I.; Milhem, M.; Collichio, F.; Delman, K.A.; Amatruda, T.; Zager, J.S.; Cranmer, L.; Hsueh, E.; et al. Patterns of Clinical Response with Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC) in Patients with Melanoma Treated in the OPTiM Phase III Clinical Trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 4169–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Puzanov, I.; Milhem, M.M.; Minor, D.; Hamid, O.; Li, A.; Chen, L.; Chastain, M.; Gorski, K.S.; Anderson, A.; Chou, J.; et al. Talimogene laherparepvec in combination with ipilimumab in previously untreated, unresectable stage IIIB-IV melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. Am. Soc. 2016, 34, 2619–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Todo, T.; Martuza, R.L.; Rabkin, S.D.; Johnson, P.A. Oncolytic herpes simplex virus vector with enhanced MHC class I presentation and tumor cell killing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 6396–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, W.; Hu, P.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Lei, L.; Liu, R. The oncolytic herpes simplex virus vector G47Δ effectively targets breast cancer stem cells. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 29, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Todo, T. ATIM-14. Results of phase II clinical trial of oncolytic herpes virus G47Δ in patients with glioblastoma. Neuro. Oncol. 2019, 21, vi4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambara, H.; Okano, H.; Chiocca, E.A.; Saeki, Y. An oncolytic HSV-1 mutant expressing ICP34.5 under control of a nestin promoter increases survival of animals even when symptomatic from a brain tumor. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 2832–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiocca, E.A.; Nakashima, H.; Kasai, K.; Fernandez, S.A.; Oglesbee, M. Preclinical Toxicology of rQNestin34.5v.2: An Oncolytic Herpes Virus with Transcriptional Regulation of the ICP34.5 Neurovirulence Gene. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 17, 871–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassady, K.A.; Parker, J.N. Herpesvirus Vectors for Therapy of Brain Tumors. Open Virol. J. 2010, 4, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, D.M.; Foreman, P.M.; Nabors, L.B.; Riley, K.O.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Markert, J.M. Design of a Phase i Clinical Trial to Evaluate M032, a Genetically Engineered HSV-1 Expressing IL-12, in Patients with Recurrent/Progressive Glioblastoma Multiforme, Anaplastic Astrocytoma, or Gliosarcoma. Hum. Gene Ther. Clin. Dev. 2016, 27, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.N.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Love, C.E.; Randall, S.; Whitley, R.J.; Markert, J.M. Engineered herpes simplex virus expressing IL-12 in the treatment of experimental murine brain tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 2208–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, E.M.; Farkaly, T.; Behera, P.; Colthart, A.; Goshert, C.; Jacques, J.; Grant, K.; Grzesik, P.; Lerr, J.; Salta, L.V.; et al. Abstract 1455: Design of ONCR-177 base vector, a next generation oncolytic herpes simplex virus type-1, optimized for robust oncolysis, transgene expression and tumor-selective replication. Immunol. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 1455. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, E.M.; Farkaly, T.; Grzesik, P.; Lee, J.; Denslow, A.; Hewett, J.; Bryant, J.; Behara, P.; Goshert, C.; Wambua, D.; et al. Design of an interferon-resistant oncolytic HSV-1 incorporating redundant safety modalities for improved tolerability. Mol. Ther. Oncol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassady, K.A. Human Cytomegalovirus TRS1 and IRS1 Gene Products Block the Double-Stranded-RNA-Activated Host Protein Shutoff Response Induced by Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Infection. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 8707–8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, A.C.; Parker, J.N.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Lakeman, F.D.; Meleth, S.; Markert, J.M.; Cassady, K.A. Enhanced antiglioma activity of chimeric HCMV/HSV-1 oncolytic viruses. Gene Ther. 2007, 14, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, S.; Kuncheria, L.; Roulstone, V.; Kyula, J.N.; Mansfield, D.; Bommareddy, P.K.; Smith, H.; Kaufman, H.L.; Harrington, K.J.; Coffin, R.S. Development of a new fusion-enhanced oncolytic immunotherapy platform based on herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, S.; Kuncheria, L.; Roulstone, V.; Kyula, J.N.; Kaufman, H.L.; Harrington, K.J.; Coffin, R.S. Abstract 1470: Development & characterization of a new oncolytic immunotherapy platform based on herpes simplex virus type 1. In Proceedings of the AACR Annual Meeting 2019, Atlanta, GA, USA, 29 March–3 April 2019; Volume 79, p. 1470. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, M.; Chung, R.Y.; Antonio Chiocca, E. An oncolytic viral mutant that delivers the CYP2B1 transgene and augments cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998, 16, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, T.M.; Nakamura, H.; Yoon, S.S.; Mullen, J.T.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Chiocca, E.A.; Tanabe, K.K. Oncolysis of diffuse hepatocellular carcinoma by intravascular administration of a replication-competent, genetically engineered herpesvirus. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 2790–2795. [Google Scholar]

- Currier, M.A.; Gillespie, R.A.; Sawtell, N.M.; Mahller, Y.Y.; Stroup, G.; Collins, M.H.; Kambara, H.; Chiocca, E.A.; Cripe, T.P. Efficacy and safety of the oncolytic herpes simplex virus rRp450 alone and combined with cyclophosphamide. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Studebaker, A.W.; Hutzen, B.J.; Pierson, C.R.; Haworth, K.B.; Cripe, T.P.; Jackson, E.M.; Leonard, J.R. Oncolytic Herpes Virus rRp450 Shows Efficacy in Orthotopic Xenograft Group 3/4 Medulloblastomas and Atypical Teratoid/Rhabdoid Tumors. Mol. Ther. Oncol. 2017, 6, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Virus Strain | Modifications | Aim |

|---|---|---|

| G207 | insertion of the Escherichia coli lacZ sequence at ICP6/UL39 | reducing ribonucleotide reductase activity [14] |

| deletion of γ34.5/RL1 | reducing neurovirulence [15] | |

| 1716 | deletion of γ34.5/RL1 | reducing neurovirulence [15] |

| HF10 | deletion in the Bam HI-B fragment | unknown |

| two incomplete UL56 copies without promoter | possibly reducing neurovirulence [16] | |

| reduced expression of UL43, UL49.5, UL55, LAT | possible influence on immunogenicity (UL43), unknown (UL49.5), reduced virus reactivation (LAT) [17] | |

| increased expression of UL53 and UL54 | reduced viral shedding (UL53) [17] | |

| NV1020 | deletion of one allele of α0, α4, γ34.5 and UL56 | reducing infectivity, viral replication and neuroinvasiveness [18] |

| Talimogene laherparepvec (T-Vec) | deletion of ICP34.5 | reducing neurovirulence [15] |

| deletion of ICP47 | augment immune response [19] | |

| insertion of GM-CSF gene | augment immune response [19] |

| Virus | Study Title | Study Type | Disease Type | Study Aim | Status | NCT/UMIN # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF10 | A study of TBI-1401(HF10) in patients with solid tumors with superficial lesions | phase I | solid tumors | safety and tolerability of repeated intratumoral injections | completed | NCT02428036 |

| Phase I Study of TBI-1401(HF10) plus chemotherapy in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer | phase I | stage III/IV unresectable pancreatic cancer | dose determination of combined treatment of HF10 with Gemcitabine+Nab-paclitaxel or TS-1 | active, not recruiting | NCT03252808 | |

| Study of HF10 in patients with refractory head and neck cancer or solid tumors with cutaneous and/or superficial lesions | phase I | refractory head and neck cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, skin carcinoma of the breast, malignant melanoma | dose escalation study for single and repeated intratumoral injections, assessment of local tumor response | completed | NCT01017185 | |

| A study of combination with TBI-1401(HF10) and ipilimumab in Japanese patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma | phase II | stage IIIB, IIIC, or IV unresectable or metastatic malignant melanoma | safety and efficacy of repeated administration of intratumoral injections of HF10 in combination with ipilimumab, best overall response rate | completed | NCT03153085 | |

| A study of combination treatment with HF10 and ipilimumab in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma | phase II | stage IIIB, IIIC, or IV unresectable or metastatic melanoma | efficacy of the combination of HF10 with ipilimumab, best overall response rate | completed | NCT02272855 | |

| G207 | HSV G207 alone or with a single radiation dose in children with progressive or recurrent supratentorial brain tumors | phase I | recurrent or progressive supratentorial neoplasms, malignant glioma, glioblastoma, anaplastic astrocytoma, PNET, cerebral primitive neuroectodermal tumor, embryonal tumor | safety and tolerability of intratumoral injection, also in combination with a single low dose of radiation | active, not recruiting | NCT02457845 |

| HSV G207 in children with recurrent or refractory cerebellar brain tumors | phase I | recurrent or refractory medulloblastoma, glioblastoma multiforme, giant cell glioblastoma, anaplastic astrocytoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, ependymoma, atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor, germ cell tumor, other high-grade malignant tumor | safety and tolerability of intratumoral injection, also in combination with a single low dose of radiation | recruiting | NCT03911388 | |

| HSV G207 with a single radiation dose in children with recurrent high-grade glioma | phase II | recurrent/progressive high grade glioma including glioblastoma multiforme, giant cell glioblastoma, anaplastic astrocytoma, midline diffuse glioma | efficacy and safety of intratumoral inoculation of G207 combined with a single radiation dose | not yet recruiting | NCT04482933 | |

| G47Δ | A clinical study of G47delta oncolytic virus therapy for progressive glioblastoma | phase I/II | recurrent/progressive glioblastoma | safety and efficacy of intratumoral inoculation of G47Δ | completed | UMIN000002661 |

| A clinical study of an oncolytic HSV-1 G47delta for patients with castration resistant prostate cancer | phase I | castration resistant prostate cancer | safety and efficacy of intratumoral inoculation of G47Δ | completed | UMIN000010463 | |

| A clinical study of G47delta oncolytic virus therapy for progressive olfactory neuroblastoma | n/a | recurrent olfactory neuroblastoma | safety and efficacy of intratumoral inoculation of G47Δ | recruiting | UMIN000011636 | |

| A clinical study of G47delta oncolytic virus therapy for progressive malignant pleural mesothelioma | phase I | inoperable/recurrent/progressive malignant pleural mesothelioma | safety and efficacy of inoculation of G47Δ into the pleural cavity | recruiting | UMIN000034063 | |

| Talimogene laherparepvec | Talimogene laherparepvec in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer | phase I/II | triple negative breast carcinoma | determination of the maximum tolerated dose of talimogene laherparepvec administered with paclitaxel- doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide, pathological complete response rate | active, not recruiting | NCT02779855 |

| T-VEC in non-melanoma skin cancer | phase I | locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell, carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma or cutaneous T cell lymphoma | detection of local immune effects after talimogene laherparepvec injection | recruiting | NCT03458117 | |

| Ipilimumab, nivolumab, and talimogene laherparepvec before surgery in treating participants with localized, triple- negative or estrogen receptor positive, HER2 negative breast cancer | phase I | triple negative or ER positive HER2 negative infiltrating ductal breast cancer | safety of combined treatment of talimogene laherparepvec with nivolumab and ipilimumab | recruiting | NCT04185311 | |

| Talimogene laherparepvec in treating patients with recurrent breast cancer that cannot be removed by surgery | phase II | recurrent stage IV breast cancer | determination of talimogene laherparepvec efficacy with overall response rate (ORR) | active, not yet recruiting | NCT02658812 | |

| Talimogene laherparepvec and nivolumab in treating patients with refractory lymphomas or advanced or refractory non-melanoma skin cancers | phase II | T cell and NK cell lymphomas, Merkel cell carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, Other non-melanoma skin cancers | response rate to talimogene laherparepvec, also in combination with nivolumab | recruiting | NCT02978625 | |

| Talimogene laherparepvec and pembrolizumab in treating patients with stage III-IV melanoma | phase II | stage IV or unresectable stage III melanoma | response rate to talimogene laherparepvec in combination with pembrolizumab | recruiting | NCT02965716 | |

| Talimogene laherparepvec, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy before surgery in treating patients with locally advanced or metastatic rectal cancer | phase I | stage III/IV rectal adenocarcinoma | dose determination and toxicity of talimogene laherparepvec in combination with capecitabibe, 5-fluoruracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, radiation | recruiting | NCT03300544 | |

| Talimogene laherparepvec with chemotherapy or endocrine therapy in treating participants with metastatic, unresectable, or recurrent HER2- negative breast cancer | phase Ib | HER2-negative, estrogen receptor positive stage III/IV breast carcinoma | safety and tolerability of talimogene laherparepvec in combination with either chemotherapy (paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel, or gemcitabine/carboplatin) or endocrine therapy | recruiting | NCT03554044 | |

| Talimogene laherparepvec and panitumumab for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin | phase I | locally advanced or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin | safety and efficacy of combined talimogene laherparepvec and panitumumab | recruiting | NCT04163952 | |

| Talimogene laherparepvec and radiation therapy in treating patients with newly diagnosed soft tissue sarcoma that can be removed by surgery | phase II | liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS)/ malignant fibrous histiosarcoma (MFH) | evaluation of the pathologic complete necrosis rate and safety following neoadjuvant treatment with talimogene laherparepvec and radiation | recruiting | NCT02923778 | |

| A Phase 1, multi-center, open-label, dose de-escalation study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Talimogene laherparepvec in pediatric subjects with advanced non-CNS tumors that are amenable to direct injection | phase I | recurring non-CNS solid tumor | safety and efficacy | recruiting | NCT02756845 | |

| ONCR-177 | Study of ONCR-177 alone and in combination with PD-1 blockade in adult subjects with advanced and/or refractory cutaneous, subcutaneous or metastatic nodal solid tumors | phase I | advanced or metastatic solid tumors | determination of the maximum tolerated dose as well as preliminary efficacy of ONCR-177 in combination with pembrolizumab | recruiting | NCT04348916 |

| RP2 | Study of RP2 monotherapy and RP2 in combination with nivolumab in patients with solid tumors | phase I | advanced or metastatic non-neurological solid tumors | safety and tolerability of RP2, also in combination with nivolumab | recruiting | NCT04336241 |

| RP1 | Study evaluating cemiplimab alone and combined with RP1 in treating advanced squamous skin cancer | phase II | locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | determination of the clinical response rate/overall response rate of cemiplimab monotherapy versus combination with RP1 | recruiting | NCT04050436 |

| Study of RP1 monotherapy and RP1 in combination with nivolumab | phase I/II | advanced and/or refractory solid tumors | determination of the maximum tolerated dose as well as preliminary efficacy of RP1 in combination with nivolumab | recruiting | NCT03767348 | |

| A Phase 1b study of RP1 in transplant patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | phase I | recurrent, locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | safety and tolerability | recruiting | NCT04349436 | |

| rQNestin | A study of the treatment of recurrent malignant glioma with rQNestin34.5v.2 | phase I | astrocytoma, malignant astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma, mixed oligo-astrocytoma | safety and dose determination of rQNestin with or without previous immunomodulation with cyclophosphamide | recruiting | NCT03152318 |

| M032 | Genetically engineered HSV-1 Phase 1 study for the treatment of recurrent malignant glioma | phase I | recurrent or progressive glioblastoma multiforme, anaplastic astrocytoma, gliosarcoma | safety and tolerability | recruiting | NCT02062827 |

| C134 | Trial of C134 in patients with recurrent GBM | phase I | recurrent or progressive glioblastoma multiforme, anaplastic astrocytoma, gliosarcoma | safety and tolerability | recruiting | NCT03657576 |

| Rrp450 | rRp450-Phase I trial in liver metastases and primary liver tumors | phase I | liver metastases or primary liver cancer | safety and tolerability | recruiting | NCT01071941 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koch, M.S.; Lawler, S.E.; Chiocca, E.A. HSV-1 Oncolytic Viruses from Bench to Bedside: An Overview of Current Clinical Trials. Cancers 2020, 12, 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123514

Koch MS, Lawler SE, Chiocca EA. HSV-1 Oncolytic Viruses from Bench to Bedside: An Overview of Current Clinical Trials. Cancers. 2020; 12(12):3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123514

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoch, Marilin S., Sean E. Lawler, and E. Antonio Chiocca. 2020. "HSV-1 Oncolytic Viruses from Bench to Bedside: An Overview of Current Clinical Trials" Cancers 12, no. 12: 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123514

APA StyleKoch, M. S., Lawler, S. E., & Chiocca, E. A. (2020). HSV-1 Oncolytic Viruses from Bench to Bedside: An Overview of Current Clinical Trials. Cancers, 12(12), 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123514