Targeting Epithelial Mesenchymal Plasticity in Pancreatic Cancer: A Compendium of Preclinical Discovery in a Heterogeneous Disease

Abstract

:1. Pancreatic Cancer, Tumour Heterogeneity, and Carcinoma Vulnerabilities

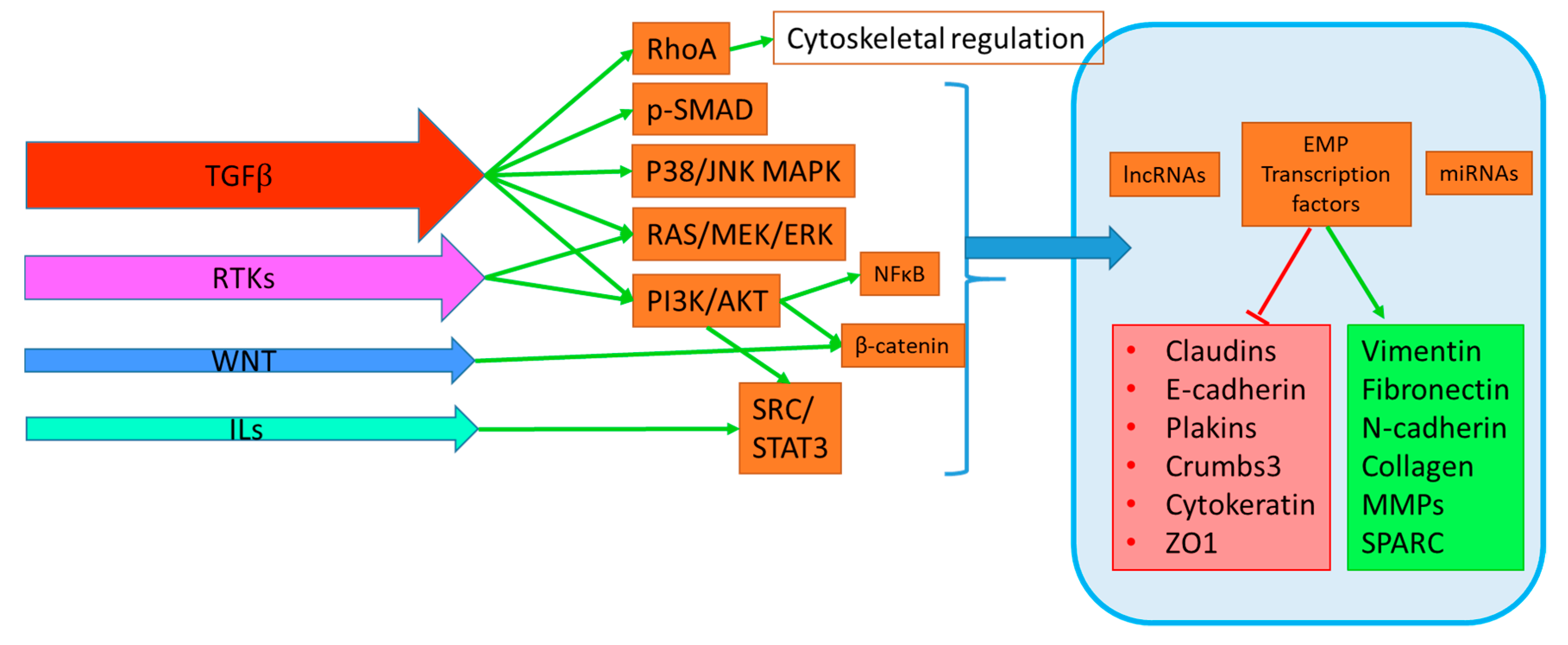

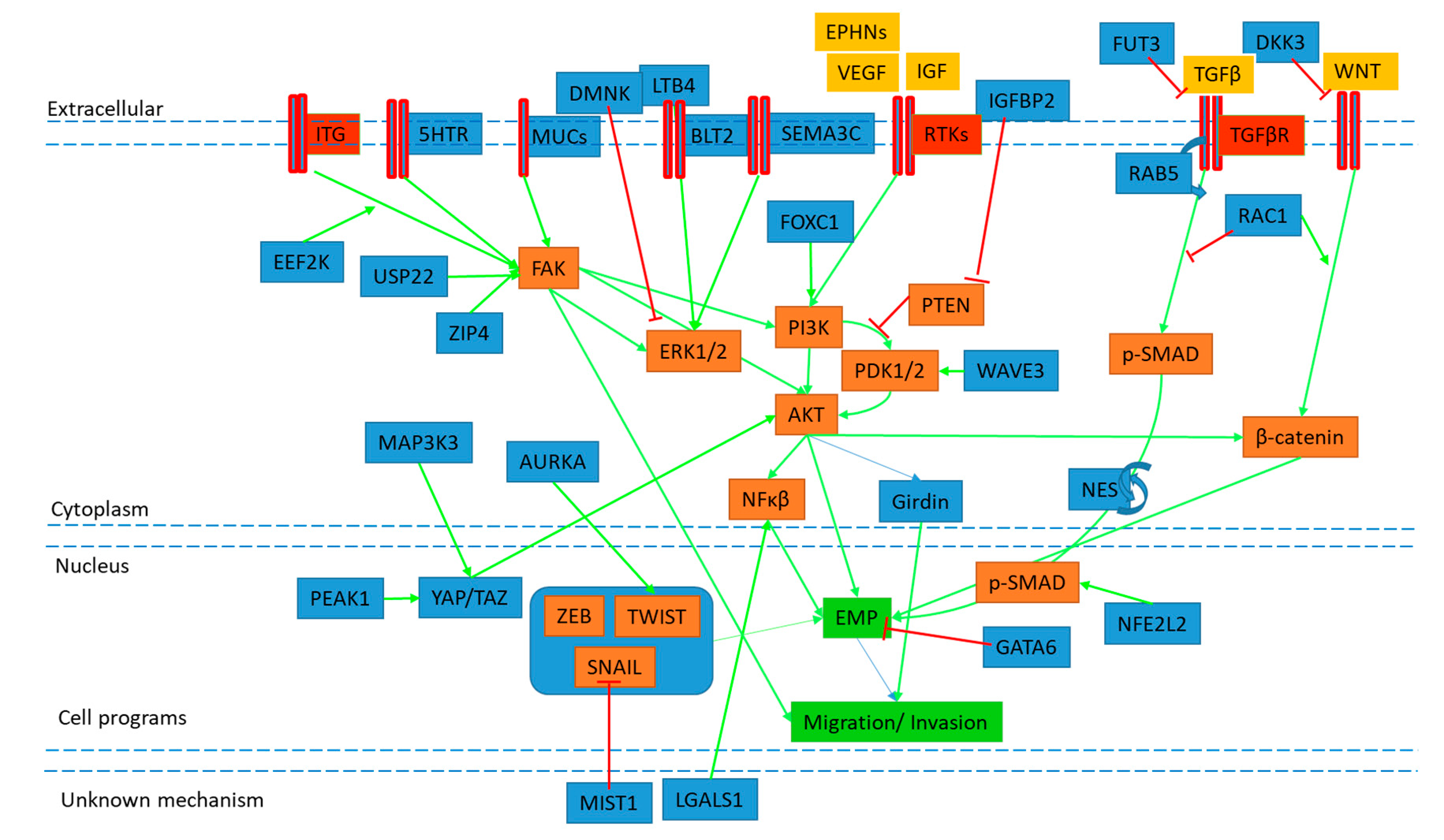

2. EMP and PDAC Progression

3. In Vitro EMP Models and Exogenous Stimuli

4. Pre-Clinical Discovery of EMP Targets

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahib, L.; Smith, B.D.; Aizenberg, R.; Rosenzweig, A.B.; Fleshman, J.M.; Matrisian, L.M. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the united states. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2913–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, J.N.; Collisson, E.A.; Mills, G.B.; Shaw, K.R.; Ozenberger, B.A.; Ellrott, K.; Shmulevich, I.; Sander, C.; Stuart, J.M. The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, N.; Pajic, M.; Patch, A.M.; Chang, D.K.; Kassahn, K.S.; Bailey, P.; Johns, A.L.; Miller, D.; Nones, K.; Quek, K.; et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 518, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bailey, P.; Chang, D.K.; Nones, K.; Johns, A.L.; Patch, A.-M.; Gingras, M.-C.; Miller, D.K.; Christ, A.N.; Bruxner, T.J.C.; Quinn, M.C.; et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2016, 531, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, A.; Hruban, R.H. Pancreatic cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008, 3, 157–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Zhang, X.; Parsons, D.W.; Lin, J.C.; Leary, R.J.; Angenendt, P.; Mankoo, P.; Carter, H.; Kamiyama, H.; Jimeno, A.; et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science 2008, 321, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.; Hruban, H.R.R.; Aguirre, A.J.; Moffitt, R.A.; Yeh, J.J.; Chip, S.A.; Robertson, G.; Cherniack, A.D.; Gupta, M.; Getz, G.; et al. Integrated genomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 185–203.e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruban, R.H.; Maitra, A.; Schulick, R.; Laheru, D.; Herman, J.; Kern, S.E.; Goggins, M. Emerging molecular biology of pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest. Cancer Res. GCR 2008, 2, S10–S15. [Google Scholar]

- Collisson, E.A.; Sadanandam, A.; Olson, P.; Gibb, W.J.; Truitt, M.; Gu, S.; Cooc, J.; Weinkle, J.; Kim, G.E.; Jakkula, L.; et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, C.; Holmstrom, S.R.; He, J.; Laise, P.; Su, T.; Ahmed, A.; Hibshoosh, H.; Chabot, J.A.; Oberstein, P.E.; Sepulveda, A.R.; et al. Experimental microdissection enables functional harmonisation of pancreatic cancer subtypes. Gut 2019, 68, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, H.; Yan, H. Gene expression profiling of 1200 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals novel subtypes. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligorio, M.; Sil, S.; Malagon-Lopez, J.; Nieman, L.T.; Misale, S.; Di Pilato, M.; Ebright, R.Y.; Karabacak, M.N.; Kulkarni, A.S.; Liu, A.; et al. Stromal microenvironment shapes the intratumoral architecture of pancreatic cancer. Cell 2019, 178, 160–175.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Sun, B.-F.; Chen, C.-Y.; Zhou, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-S.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Huang, D.; Jiang, J.; Cui, G.-S.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intra-tumoral heterogeneity and malignant progression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, R.A.; Marayati, R.; Flate, E.L.; Volmar, K.E.; Loeza, S.G.H.; Hoadley, K.A.; Rashid, N.U.; Williams, L.A.; Eaton, S.C.; Chung, A.H.; et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak-Kroizman, T.R.; Hostetter, G.; Posner, R.; Aziz, M.; Hu, C.; Demeure, M.J.; Von Hoff, D.; Hingorani, S.R.; Palculict, T.B.; Izzo, J.; et al. Hypoxia triggers hedgehog-mediated tumor-stromal interactions in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3235–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, J.A.; Mann, J.; White, S.A. The role of pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic cancer. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 24, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feig, C.; Gopinathan, A.; Neesse, A.; Chan, D.S.; Cook, N.; Tuveson, D.A. The Pancreas Cancer Microenvironment; AACR: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Neesse, A.; Michl, P.; Frese, K.K.; Feig, C.; Cook, N.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Lolkema, M.P.; Buchholz, M.; Olive, K.P.; Gress, T.M. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut 2011, 60, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korc, M. Pancreatic cancer–associated stroma production. Am. J. Surg. 2007, 194, S84–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Pothula, S.P.; Wilson, J.S.; Apte, M.V. Pancreatic cancer and its stroma: A conspiracy theory. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2014, 20, 11216–11229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahadevan, D.; Von Hoff, D.D. Tumor-stroma interactions in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cancer Therap. 2007, 6, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, D.; Radhakrishnan, P. Tumor-stromal crosstalk in pancreatic cancer and tissue fibrosis. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trelstad, R.L.; Hay, E.D.; Revel, J.D. Cell contact during early morphogenesis in the chick embryo. Dev. Biol. 1967, 16, 78–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.A.; Kraut, N.; Beug, H. Molecular requirements for epithelial-mesenchymal transition during tumor progression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005, 17, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.H.; Yang, J. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in carcinoma metastasis. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 2192–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, E.; van der Borden, C.L.; Frampton, A.E.; Ali, A.; Firuzi, O.; Peters, G.J. Never let it go: Stopping key mechanisms underlying metastasis to fight pancreatic cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2017, 44, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.X.; Liu, Z.W.; You, L.; Wu, W.M.; Zhao, Y.P. Advances in understanding the molecular mechanism of pancreatic cancer metastasis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2016, 15, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuran, M.; Negoi, I.; Paun, S.; Ion, A.D.; Bleotu, C.; Negoi, R.I.; Hostiuc, S. The epithelial to mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review. Pancreatol. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Pancreatol. 2015, 15, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, K.; Hamada, S.; Shimosegawa, T. Involvement of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 50, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, S.; Satoh, K.; Masamune, A.; Shimosegawa, T. Regulators of epithelial mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bailey, J.M.; Leach, S.D. Signaling pathways mediating epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk in pancreatic cancer: Hedgehog, Notch and TGFBeta. In Pancreatic Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment; Grippo, P.J., Munshi, H.G., Eds.; Transworld Research Network: Trivandrum, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dangi-Garimella, S.; Krantz, S.B.; Shields, M.A.; Grippo, P.J.; Munshi, H.G. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and pancreatic cancer progression. In Pancreatic Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment; Grippo, P.J., Munshi, H.G., Eds.; Transworld Research Network: Trivandrum, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffer, C.L.; San Juan, B.P.; Lim, E.; Weinberg, R.A. EMT, cell plasticity and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016, 35, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trager, M.M.; Dhayat, S.A. Epigenetics of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elaskalani, O.; Razak, N.B.; Falasca, M.; Metharom, P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition as a therapeutic target for overcoming chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 9, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaianigo, N.; Melisi, D.; Carbone, C. EMT and treatment resistance in pancreatic cancer. Cancers 2017, 9, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, T. Cancer stem cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition: Novel therapeutic targets for cancer. Pathol. Int. 2016, 66, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyuno, D.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ito, T.; Kono, T.; Kimura, Y.; Imamura, M.; Konno, T.; Hirata, K.; Sawada, N.; Kojima, T. Targeting tight junctions during epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2014, 20, 10813–10824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibue, T. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: The mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawa, Z.; Haque, I.; Ghosh, A.; Banerjee, S.; Harris, L.; Banerjee, S.K. The miRacle in pancreatic cancer by miRNAs: Tiny angels or devils in disease progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabletz, S.; Brabletz, T. The ZEB/miR-200 feedback loop—A motor of cellular plasticity in development and cancer? EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhim, A.D. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition and the generation of stem-like cells in pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology 2013, 13, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhan, H.X.; Xu, J.W.; Wu, D.; Zhang, T.P.; Hu, S.Y. Pancreatic cancer stem cells: New insight into a stubborn disease. Cancer Lett. 2015, 357, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaz, A.P.; Ponnusamy, M.P.; Seshacharyulu, P.; Batra, S.K. A concise review on the current understanding of pancreatic cancer stem cells. J. Cancer Stem Cell Res. 2014, 2, e1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellanos, J.A.; Merchant, N.B.; Nagathihalli, N.S. Emerging targets in pancreatic cancer: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2013, 6, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamitopoulou, E. Tumor budding cells, cancer stem cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition-type cells in pancreatic cancer. Front. Oncol. 2012, 2, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuai, G.; Yang, F.; Yan, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, C.; Gu, F.; Liu, Q. Deciphering relationship between microhomology and in-frame mutation occurrence in human CRISPR-based gene knockout. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2016, 5, e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.X.; Bos, P.D.; Massague, J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, J.; Grossbard, M.L.; Kozuch, P. Metastatic pancreatic cancer 2008: Is the glass less empty? Oncologist 2008, 13, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalhofer, O.; Brabletz, S.; Brabletz, T. E-cadherin, beta-catenin, and ZEB1 in malignant progression of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009, 28, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, S.; Doi, R.; Toyoda, E.; Tsuji, S.; Wada, M.; Koizumi, M.; Tulachan, S.S.; Ito, D.; Kami, K.; Mori, T.; et al. N-cadherin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 4125–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peinado, H.; Portillo, F.; Cano, A. Transcriptional regulation of cadherins during development and carcinogenesis. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2004, 48, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hotz, B.; Arndt, M.; Dullat, S.; Bhargava, S.; Buhr, H.J.; Hotz, H.G. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition: Expression of the regulators snail, slug, and twist in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 4769–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabletz, T.; Jung, A.; Reu, S.; Porzner, M.; Hlubek, F.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A.; Knuechel, R.; Kirchner, T. Variable beta-catenin expression in colorectal cancers indicates tumor progression driven by the tumor environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10356–10361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.E.; Rew, J.S.; Park, C.S.; Kim, S.J. Expression of E-cadherin, alpha- and beta-catenins in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreatol. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Pancreatol. 2002, 2, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Wang, C.; Liu, T.; Zhao, G.; Zha, Y.; Yang, M. Expression of snail in pancreatic cancer promotes metastasis and chemoresistance. J. Surg. Res. 2007, 141, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oida, Y.; Yamazaki, H.; Tobita, K.; Mukai, M.; Ohtani, Y.; Miyazaki, N.; Abe, Y.; Imaizumi, T.; Makuuchi, H.; Ueyama, Y.; et al. Increased S100A4 expression combined with decreased E-cadherin expression predicts a poor outcome of patients with pancreatic cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2006, 16, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javle, M.M.; Gibbs, J.F.; Iwata, K.K.; Pak, Y.; Rutledge, P.; Yu, J.; Black, J.D.; Tan, D.; Khoury, T. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-Erk) in surgically resected pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 14, 3527–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Fuchs, B.C.; Fujii, T.; Shimoyama, Y.; Sugimoto, H.; Nomoto, S.; Takeda, S.; Tanabe, K.K.; Kodera, Y.; Nakao, A. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition predicts prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Surgery 2013, 154, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Nikhil, K.; Viccaro, K.; Chang, L.; Jacobsen, M.; Sandusky, G.; Shah, K. The Aurora-A-Twist1 axis promotes highly aggressive phenotypes in pancreatic carcinoma. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 1078–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, C. Snail transcript levels in diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma with fine-needle aspirate. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2015, 72, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, K.; Masugi, Y.; Effendi, K.; Tsujikawa, H.; Hiraoka, N.; Kitago, M.; Shinoda, M.; Itano, O.; Tanabe, M.; Kitagawa, Y.; et al. Upregulated SMAD3 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and predicts poor prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Lab. Investing. J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 2014, 94, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masugi, Y.; Yamazaki, K.; Hibi, T.; Aiura, K.; Kitagawa, Y.; Sakamoto, M. Solitary cell infiltration is a novel indicator of poor prognosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Hum. Pathol. 2010, 41, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvan, J.A.; Zlobec, I.; Wartenberg, M.; Lugli, A.; Gloor, B.; Perren, A.; Karamitopoulou, E. Expression of E-cadherin repressors SNAIL, ZEB1 and ZEB2 by tumour and stromal cells influences tumour-budding phenotype and suggests heterogeneity of stromal cells in pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 1944–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tarin, D.; Thompson, E.W.; Newgreen, D.F. The fallacy of epithelial mesenchymal transition in neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 5996–6000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, H. Cancer theory faces doubts. Nature 2011, 472, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, A.D.; Mirek, E.T.; Aiello, N.M.; Maitra, A.; Bailey, J.M.; McAllister, F.; Reichert, M.; Beatty, G.L.; Rustgi, A.K.; Vonderheide, R.H.; et al. EMT and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell 2012, 148, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Carstens, J.L.; Kim, J.; Scheible, M.; Kaye, J.; Sugimoto, H.; Wu, C.C.; LeBleu, V.S.; Kalluri, R. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is dispensable for metastasis but induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 527, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aiello, N.M.; Brabletz, T.; Kang, Y.; Nieto, M.A.; Weinberg, R.A.; Stanger, B.Z. Upholding a role for EMT in pancreatic cancer metastasis. Nature 2017, 547, E7–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, A.M.; Mitschke, J.; Lasierra Losada, M.; Schmalhofer, O.; Boerries, M.; Busch, H.; Boettcher, M.; Mougiakakos, D.; Reichardt, W.; Bronsert, P.; et al. The EMT-activator Zeb1 is a key factor for cell plasticity and promotes metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; LeBleu, V.S.; Carstens, J.L.; Sugimoto, H.; Zheng, X.; Malasi, S.; Saur, D.; Kalluri, R. Dual reporter genetic mouse models of pancreatic cancer identify an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-independent metastasis program. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, e9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, E.W.; Nagaraj, S.H. Transition states that allow cancer to spread. Nature 2018, 556, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastushenko, I.; Brisebarre, A.; Sifrim, A.; Fioramonti, M.; Revenco, T.; Boumahdi, S.; Van Keymeulen, A.; Brown, D.; Moers, V.; Lemaire, S.; et al. Identification of the tumour transition states occurring during EMT. Nature 2018, 556, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastushenko, I.; Blanpain, C. EMT Transition states during tumor progression and metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabletz, S.; Brabletz, T.; Stemmler, M.P. Road to perdition: Zeb1-dependent and -independent ways to metastasis. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 1729–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, D.M.; Medici, D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci. Signal. 2014, 7, re8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, C.J.; Huang, Y.-H.; Chen, M.; Su, J.; Zou, Y.; Bardeesy, N.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C.A.; Massagué, J. TGF-β Tumor Suppression through a Lethal EMT. Cell 2016, 164, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazer, E.S.; Welsh, E.; Pimiento, J.M.; Teer, J.K.; Malafa, M.P. TGFβ1 overexpression is associated with improved survival and low tumor cell proliferation in patients with early-stage pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland-Goldsmith, M.A.; Maruyama, H.; Kusama, T.; Ralli, S.; Korc, M. Soluble type II transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) receptor inhibits TGF-beta signaling in COLO-357 pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and attenuates tumor formation. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 2931–2940. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M.; Kleeff, J.; Friess, H.; Buchler, M.W.; Korc, M. Enhanced expression of the type II transforming growth factor-beta receptor is associated with decreased survival in human pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 1999, 19, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuvin, N.; Vincent, D.F.; Pommier, R.M.; Alcaraz, L.B.; Gout, J.; Caligaris, C.; Yacoub, K.; Cardot, V.; Roger, E.; Kaniewski, B.; et al. Acinar-to-Ductal Metaplasia Induced by Transforming Growth Factor Beta Facilitates KRAS(G12D)-driven Pancreatic Tumorigenesis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 4, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, G.; Schwarz, R.E.; Higgins, L.; McEnroe, G.; Chakravarty, S.; Dugar, S.; Reiss, M. Targeting endogenous transforming growth factor beta receptor signaling in SMAD4-deficient human pancreatic carcinoma cells inhibits their invasive phenotype1. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5200–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janda, E.; Lehmann, K.; Killisch, I.; Jechlinger, M.; Herzig, M.; Downward, J.; Beug, H.; Grunert, S. Ras and TGF[beta] cooperatively regulate epithelial cell plasticity and metastasis: Dissection of Ras signaling pathways. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 156, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ismaeel, Q.; Neal, C.P.; Al-Mahmoodi, H.; Almutairi, Z.; Al-Shamarti, I.; Straatman, K.; Jaunbocus, N.; Irvine, A.; Issa, E.; Moreman, C.; et al. ZEB1 and IL-6/11-STAT3 signaling cooperate to define invasive potential of pancreatic cancer cells via differential regulation of the expression of S100 proteins. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram Makena, M.; Gatla, H.; Verlekar, D.; Sukhavasi, S.; Pandey, M.K.; Pramanik, K.C. Wnt/beta-Catenin signaling: The culprit in pancreatic carcinogenesis and therapeutic resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, D.; Otterbein, H.; Forster, M.; Giehl, K.; Zeiser, R.; Lehnert, H.; Ungefroren, H. Negative regulation of TGF-beta1-induced MKK6-p38 and MEK-ERK signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by Rac1b. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yu, Y.; Sun, C.; Liu, T.; Liang, T.; Zhan, L.; Lin, X.; Feng, X.H. STAT3 selectively interacts with Smad3 to antagonize TGF-beta signaling. Oncogene 2016, 35, 4388–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Chen, C.; Dong, M.; Wang, G.; Zhou, J.; Song, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ding, S. Calreticulin promotes EGF-induced EMT in pancreatic cancer cells via Integrin/EGFR-ERK/MAPK signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, D.; Bartscht, T.; Kaufmann, R.; Pries, R.; Settmacher, U.; Lehnert, H.; Ungefroren, H. TGF-beta1-induced cell migration in pancreatic carcinoma cells is RAC1 and NOX4-dependent and requires RAC1 and NOX4-dependent activation of p38 MAPK. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 3693–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Chow, C.R.; Ebine, K.; Arslan, A.D.; Kwok, B.; Bentrem, D.J.; Eckerdt, F.D.; Platanias, L.C.; Munshi, H.G. Differential regulation of ZEB1 and EMT by MAPK-interacting protein Kinases (MNK) and eIF4E in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR 2016, 14, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.D.; Camp, E.R.; Fan, F.; Shen, L.; Gray, M.J.; Liu, W.; Somcio, R.; Bauer, T.W.; Wu, Y.; Hicklin, D.J.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 activation mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, G.; Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Hu, W.; Li, P.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Kong, X.; Gao, J.; et al. Hedgehog Signaling non-canonical activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Cancer 2016, 7, 2067–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Svoboda, R.A.; Lazenby, A.J.; Saowapa, J.; Chaika, N.; Ding, K.; Wheelock, M.J.; Johnson, K.R. Up-regulation of N-cadherin by collagen i-activated discoidin domain receptor 1 in pancreatic cancer requires the adaptor molecule Shc1. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 23208–23223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Qin, H.; Li, D.M.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Q. Effect of PPM1H on malignant phenotype of human pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 2926–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellenrieder, V.; Hendler, S.F.; Boeck, W.; Activation, S.-R.K.; Seufferlein, T.; Menke, A.; Ruhland, C.; Adler, G.; Gress, T.M. Transforming growth factor β 1 treatment leads to an epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation of pancreatic cancer cells requiring extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 activation. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4222–4228. [Google Scholar]

- Buonato, J.M.; Lan, I.S.; Lazzara, M.J. EGF augments TGFBeta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by promoting SHP2 binding to GAB1. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 3898–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, H.J.; Schmidt-Strassburger, U.; Huber, M.A.; Wiedemann, E.M.; Beug, H.; Wirth, T. NF-kappaB promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration and invasion of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2010, 295, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyanagi, J.; Kojima, N.; Sato, H.; Higashi, S.; Kikuchi, K.; Sakai, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Miyazaki, K. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling potentiates tumor cell invasion into collagen matrix induced by fibroblast-derived hepatocyte growth factor. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 326, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajant, H.; Pfizenmaier, K.; Scheurich, P. Tumor necrosis factor signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2003, 10, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, J.; Lamouille, S.; Derynck, R. TGF-β-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res. 2009, 19, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Quek, L.E.; Sultani, G.; Turner, N. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induction is associated with augmented glucose uptake and lactate production in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Metab. 2016, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Chua, C.Y.; Phillips, L.M.; Ren, H.; Fleming, J.B.; Wang, H.; et al. IGFBP2 Activates the NF-kappaB Pathway to Drive Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Invasive Character in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 6543–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masugi, Y.; Yamazaki, K.; Emoto, K.; Effendi, K.; Tsujikawa, H.; Kitago, M.; Itano, O.; Kitagawa, Y.; Sakamoto, M. Upregulation of integrin beta4 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and is a novel prognostic marker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Lab. Investig. J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 2015, 95, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Q.; An, Y.; Lv, N.; Xue, X.; Wei, J.; Jiang, K.; Wu, J.; Gao, W.; Qian, Z.; et al. CEACAM6 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and mediates invasion and metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 43, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, S.; Stebbing, J.; Frampton, A.E.; Zagorac, S.; Krell, J.; de Giorgio, A.; Trabulo, S.M.; Nguyen, V.T.M.; Magnani, L.; Feng, H.; et al. TGF-β induces miR-100 and miR-125b but blocks let-7a through LIN28B controlling PDAC progression. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, S.; Ouyang, Y.; Yin, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, J.; Huang, W.; Qin, H.; et al. Lin28B facilitates the progression and metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 60414–60428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, Q.; Qin, W. DKK3 blocked translocation of beta-catenin/EMT induced by hypoxia and improved gemcitabine therapeutic effect in pancreatic cancer Bxpc-3 cell. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 2832–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R.; Park, M.K.; Kang, G.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, E.J.; Byun, H.J.; Lee, M.Y.; Lee, C.H. Leukotriene B4 induces EMT and vimentin expression in PANC-1 pancreatic cancer cells: Involvement of BLT2 via ERK2 activation. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Essential Fatty Acids 2016, 115, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, S.; Yu, H.; Wen, Z.; Ye, T.; Sun, H.; Kong, H.; Li, D.; Yu, D.; et al. DMKN contributes to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition through increased activation of STAT3 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 2130–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, S.; Wu, Q.; et al. PSC-derived Galectin-1 inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells by activating the NF-kappaB pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 86488–86502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; You, Y.; Ni, B.; Wang, H.; Bie, P. Increased semaphorin 3c expression promotes tumor growth and metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by activating the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2017, 397, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z. Knockdown of FUT3 disrupts the proliferation, migration, tumorigenesis and TGF-β induced EMT in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; He, P.; Wang, J.; Schetter, A.; Tang, W.; Funamizu, N.; Yanaga, K.; Uwagawa, T.; Satoskar, A.R.; Gaedcke, J.; et al. A Novel MIF signaling pathway drives the malignant character of pancreatic cancer by targeting NR3C2. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 3838–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, H.; Zhang, S.; Gao, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chang, X.; Zhu, M. Upregulation of Wnt5a promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Jin, D.Y.; Lou, W.H.; Wang, D.S. Lipocalin-2 is associated with a good prognosis and reversing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. World J. Surg. 2013, 37, 1892–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Xie, R.; Dang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Mao, S.; Chen, J.; Qu, J.; Zhang, J. NOV promoted the growth and migration of pancreatic cancer cells. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 3195–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Li, W.; Li, C.; Gao, Z.; Guo, K.; Song, S. CCL18 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion and migration of pancreatic cancer cells in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhan, H.; Tin, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, J.; Dong, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, L.; Guo, W. TUFT1 regulates metastasis of pancreatic cancer through HIF1-Snail pathway induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Lett. 2016, 382, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Yang, C.; Li, L.; Song, S.; Wu, H.; Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Gu, J. LOX-1 is a poor prognostic indicator and induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in pancreatic cancer patients. Cell. Oncol. (Dordr.) 2017, 41, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.K.; Dong, S.M.; Yoon, D.S. Emerging role of LOXL2 in the promotion of pancreas cancer metastasis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 42539–42552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, J.; Yokoyama, Y.; Kokuryo, T.; Ebata, T.; Enomoto, A.; Nagino, M. Trefoil factor 1 inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasm. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3619–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gurbuz, N.; Ashour, A.A.; Alpay, S.N.; Ozpolat, B. Down-regulation of 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors inhibits proliferation, clonogenicity and invasion of human pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramani, R.; Lopez-Valdez, R.; Arumugam, A.; Nandy, S.; Boopalan, T.; Lakshmanaswamy, R. Targeting insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor inhibits pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Gao, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Yang, P.; Kornmann, M.; Tian, X.; Yang, Y. Hedgehog signaling regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer stem-like cells. J. Cancer 2016, 7, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Huang, H.; Wang, C.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, H. Involvement of ephrin receptor A4 in pancreatic cancer cell motility and invasion. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 7, 2165–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, C.; Shi, K.; Daalhuisen, J.B.; Ten Brink, M.S.; Bijlsma, M.F.; Spek, C.A. PAR1 signaling on tumor cells limits tumor growth by maintaining a mesenchymal phenotype in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 32010–32023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, S.; Hamada, S.; Masamune, A.; Satoh, K.; Shimosegawa, T. CUB-domain containing protein 1 represses the epithelial phenotype of pancreatic cancer cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 321, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniyan, S.; Haridas, D.; Chugh, S.; Rachagani, S.; Lakshmanan, I.; Gupta, S.; Seshacharyulu, P.; Smith, L.M.; Ponnusamy, M.P.; Batra, S.K. MUC16 contributes to the metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through focal adhesion mediated signaling mechanism. Genes Cancer 2016, 7, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvedere, R.; Bizzarro, V.; Forte, G.; Dal Piaz, F.; Parente, L.; Petrella, A. Annexin A1 contributes to pancreatic cancer cell phenotype, behaviour and metastatic potential independently of Formyl Peptide Receptor pathway. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belvedere, R.; Saggese, P.; Pessolano, E.; Memoli, D.; Bizzarro, V.; Rizzo, F.; Parente, L.; Weisz, A.; Petrella, A. miR-196a Is able to restore the aggressive phenotype of annexin a1 knock-out in pancreatic cancer cells by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Ohuchida, K.; Cui, L.; Zhao, M.; Shindo, K.; Fujiwara, K.; Manabe, T.; Torata, N.; Moriyama, T.; Miyasaka, Y.; et al. TM4SF1 as a prognostic marker of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is involved in migration and invasion of cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 47, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ye, C.; Tian, X.; Yue, G.; Yan, L.; Guan, X.; Wang, S.; Hao, C. Suppression of CD26 inhibits growth and metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 15677–15686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Cui, X.; Zhang, L.; Fung, K.M.; Zheng, W.; Allard, F.D.; Yee, E.U.; et al. ZIP4 promotes pancreatic cancer progression by repressing ZO-1 and claudin-1 through a ZEB1-dependent transcriptional mechanism. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 3186–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. WAVE3 promotes proliferation, migration and invasion via the AKT pathway in pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2018, 53, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.T.; Weng, C.C.; Hsiao, P.J.; Chen, L.H.; Kuo, T.L.; Chen, Y.W.; Kuo, K.K.; Cheng, K.H. Stem cell marker nestin is critical for TGF-beta1-mediated tumor progression in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR 2013, 11, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagio, M.; Matsuda, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Ishiwata, T. Nestin regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition marker expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 1, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razidlo, G.L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Krueger, E.W.; Billadeau, D.D.; McNiven, M.A. Dynamin 2 potentiates invasive migration of pancreatic tumor cells through stabilization of the Rac1 GEF Vav1. Dev. Cell 2013, 24, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppinga, R.D.; Krueger, E.W.; Weller, S.G.; Zhang, L.; Cao, H.; McNiven, M.A. Increased expression of the large GTPase dynamin 2 potentiates metastatic migration and invasion of pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Oncogene 2012, 31, 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, T.; Araki, K.; Yokobori, T.; Altan, B.; Yamanaka, T.; Ishii, N.; Tsukagoshi, M.; Watanabe, A.; Kubo, N.; Handa, T.; et al. Association of RAB5 overexpression in pancreatic cancer with cancer progression and poor prognosis via E-cadherin suppression. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 12290–12300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashour, A.A.; Gurbuz, N.; Alpay, S.N.; Abdel-Aziz, A.A.; Mansour, A.M.; Huo, L.; Ozpolat, B. Elongation factor-2 kinase regulates TG2/beta1 integrin/Src/uPAR pathway and epithelial-mesenchymal transition mediating pancreatic cancer cells invasion. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 2235–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Zhou, Z.; He, Z. Knockdown of PFTK1 inhibits tumor cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 14005–14012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tactacan, C.M.; Phua, Y.W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Humphrey, E.S.; Cowley, M.; Pinese, M.; Biankin, A.V.; Daly, R.J. The pseudokinase SgK223 promotes invasion of pancreatic ductal epithelial cells through JAK1/Stat3 signaling. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santoro, R.; Zanotto, M.; Carbone, C.; Piro, G.; Tortora, G.; Melisi, D. MEKK3 sustains EMT and stemness in pancreatic cancer by regulating YAP and TAZ transcriptional activity. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungefroren, H.; Sebens, S.; Giehl, K.; Helm, O.; Groth, S.; Fandrich, F.; Rocken, C.; Sipos, B.; Lehnert, H.; Gieseler, F. Rac1b negatively regulates TGF-beta1-induced cell motility in pancreatic ductal epithelial cells by suppressing Smad signaling. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Wang, A.; Liang, J.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Yan, Q.; Wang, Z. USP22 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the FAK pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 32, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnadel, J.; Choi, S.; Fujimura, K.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Wyse, M.; Wright, T.; Gross, E.; Peinado, C.; Park, H.W.; et al. eIF5A-PEAK1 signaling regulates YAP1/TAZ protein expression and pancreatic cancer cell growth. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhao, Q. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha participates in hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via response gene to complement 32. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 1825–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, H.R.; Hung, S.W.; Naidu, K.; Lee, H.; Gilbert, C.A.; Hoang, T.T.; Pathak, R.K.; Manoharan, R.; Muruganandan, S.; Govindarajan, R. SET contributes to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 67966–67979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meng, Q.; Shi, S.; Liang, C.; Liang, D.; Hua, J.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Yu, X. Abrogation of glutathione peroxidase-1 drives EMT and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer by activating ROS-mediated Akt/GSK3beta/Snail signaling. Oncogene 2018, 37, 5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinke, G.; Yamada, D.; Eguchi, H.; Iwagami, Y.; Asaoka, T.; Noda, T.; Wada, H.; Kawamoto, K.; Gotoh, K.; Kobayashi, S.; et al. Role of histone deacetylase 1 in distant metastasis of pancreatic ductal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 2520–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mishra, V.K. Histone deacetylase class-I inhibition promotes epithelial gene expression in pancreatic cancer cells in a BRD4- and MYC-dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 6334–6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Duo, A.; Jia, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, B. PAFAH1B2 is a HIF1a target gene and promotes metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 501, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. KDM4B promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition through up-regulation of ZEB1 in pancreatic cancer. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2015, 47, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, W.L.; Zhang, J.H.; Wu, X.Z.; Yan, T.; Lv, W. miR-15b promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition by inhibiting SMURF2 in pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 47, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Chen, S.; Gu, J.N.; Zhu, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Cheng, D.F.; Chen, H.; Deng, X.X.; Shen, B.Y.; Peng, C.H. MicroRNA-300 promotes apoptosis and inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway by targeting CUL4B in pancreatic cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 119, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viotti, M.; Wilson, C.; McCleland, M.; Koeppen, H.; Haley, B.; Jhunjhunwala, S.; Klijn, C.; Modrusan, Z.; Arnott, D.; Classon, M.; et al. SUV420H2 is an epigenetic regulator of epithelial/mesenchymal states in pancreatic cancer. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 217, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraga, R.; Kato, M.; Miyagawa, S.; Kamata, T. Nox4-derived ROS signaling contributes to TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 4431–4438. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; You, Y.; Xu, T.; Yu, P.; Wu, D.; Deng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bie, P. Par-4 downregulation confers cisplatin resistance in pancreatic cancer cells via PI3K/Akt pathway-dependent EMT. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 224, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X. HMGN5 promotes proliferation and invasion via the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 4013–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.X.; Xu, Z.C.; Li, H.L.; Yang, P.L.; Du, J.K.; Xu, J. Overexpression of GP73 promotes cell invasion, migration and metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology 2018, 18, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Su, B.; Xie, C.; Wei, S.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Dai, W.; Cheng, P.; Wang, F.; Xu, X.; et al. Sonic hedgehog-Gli1 signaling pathway regulates the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) by mediating a new target gene, S100A4, in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inaguma, S.; Kasai, K.; Ikeda, H. GLI1 facilitates the migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells through MUC5AC-mediated attenuation of E-cadherin. Oncogene 2011, 30, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, S.; Nakamura, M.; Yanai, K.; Wada, J.; Akiyoshi, T.; Nakashima, H.; Ohuchida, K.; Sato, N.; Tanaka, M.; Katano, M. Gli1 contributes to the invasiveness of pancreatic cancer through matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaguma, S.; Kasai, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Ikeda, H. GLI1 modulates EMT in pancreatic cancer—Letter. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3702–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Xie, D.; Cui, J.; Li, Q.; Gao, Y.; Xie, K. FOXM1c promotes pancreatic cancer epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis via upregulation of expression of the urokinase plasminogen activator system. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Cui, J.; Xia, T.; Jia, Z.; Wang, L.; Wei, W.; Zhu, A.; Gao, Y.; Xie, K.; Quan, M. Hippo transducer TAZ promotes epithelial mesenchymal transition and supports pancreatic cancer progression. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35949–35963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, D.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Tian, G.; Dong, Y. YAP overexpression promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Qian, W.; Li, J.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Yan, B.; Cao, J.; Sun, L.; Zhou, C.; Lei, M.; et al. Loss of AMPK activation promotes the invasion and metastasis of pancreatic cancer through an HSF1-dependent pathway. Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 1475–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R.; Camacho, F.A.; Levin, C.I.; Flores, K.; Clift, A.; Galvez, A.; Terres, M.; Rivera, S.; Kolli, S.N.; Dodderer, J.; et al. FOXC1 plays a crucial role in the growth of pancreatic cancer. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Ye, Z.; Gou, S.; Wang, C. Overexpression of MIST1 reverses the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and reduces the tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancer cells via the Snail/E-cadherin pathway. Cancer Lett. 2018, 431, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.; Zai, H.; Long, X.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Li, Y. Kruppel-like factor 8 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and promotes invasion of pancreatic cancer cells through transcriptional activation of four and a half LIM-only protein 2. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 4883–4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.K.; Nigri, J.; Lac, S.; Leca, J.; Bressy, C.; Berthezene, P.; Bartholin, L.; Chan, P.; Calvo, E.; Iovanna, J.L.; et al. TAp73 loss favors Smad-independent TGF-β signaling that drives EMT in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1358–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takano, S.; Reichert, M.; Bakir, B.; Das, K.K.; Nishida, T.; Miyazaki, M.; Heeg, S.; Collins, M.A.; Marchand, B.; Hicks, P.D.; et al. Prrx1 isoform switching regulates pancreatic cancer invasion and metastatic colonization. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, C.; Zhan, L.; Jiang, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Pen, F.; Wang, M.; Qin, R.; Sun, C. KAP-1 is overexpressed and correlates with increased metastatic ability and tumorigenicity in pancreatic cancer. Med. Oncol. (Northwood Lond. Engl.) 2014, 31, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, R.; Shi, F.; Wang, C.; Rui, Z. Transcriptional silencing of ETS-1 abrogates epithelial-mesenchymal transition resulting in reduced motility of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfmann-Knubel, S.; Struck, B.; Genrich, G.; Helm, O.; Sipos, B.; Sebens, S.; Schafer, H. The Crosstalk between Nrf2 and TGF-beta1 in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic duct epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.; Takeuchi, K.K.; Ruggeri, J.M.; Bailey, P.; Chang, D.; Li, J.; Leonhardt, L.; Puri, S.; Hoffman, M.T.; Gao, S.; et al. PDX1 dynamically regulates pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma initiation and maintenance. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 2669–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sannino, G.; Armbruster, N.; Bodenhofer, M.; Haerle, U.; Behrens, D.; Buchholz, M.; Rothbauer, U.; Sipos, B.; Schmees, C. Role of BCL9L in transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal-transition (EMT) and metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 73725–73738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeg, S.; Das, K.K.; Reichert, M.; Bakir, B.; Takano, S.; Caspers, J.; Aiello, N.M.; Wu, K.; Neesse, A.; Maitra, A.; et al. ETS-Transcription Factor ETV1 Regulates Stromal Expansion and Metastasis in Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 540–553.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, D.; Zhou, J. HIF-2alpha promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition through regulating Twist2 binding to the promoter of E-cadherin in pancreatic cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2016, 35, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerbs, T.; Bisht, S.; Scholch, S.; Pecqueux, M.; Kristiansen, G.; Schneider, M.; Hofmann, B.T.; Welsch, T.; Reissfelder, C.; Rahbari, N.N.; et al. Inhibition of Six1 affects tumour invasion and the expression of cancer stem cell markers in pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, H.; Takano, S.; Yoshitomi, H.; Suzuki, K.; Kagawa, S.; Shimazaki, R.; Shimizu, H.; Furukawa, K.; Miyazaki, M.; Ohtsuka, M. Grainyhead-like 2 (GRHL2) regulates epithelial plasticity in pancreatic cancer progression. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 2686–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, P.; Carrillo-de Santa Pau, E.; Cox, T.; Sainz, B., Jr.; Dusetti, N.; Greenhalf, W.; Rinaldi, L.; Costello, E.; Ghaneh, P.; Malats, N.; et al. GATA6 regulates EMT and tumour dissemination, and is a marker of response to adjuvant chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, S.; Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Lou, B.; Fang, B.; Ye, T.; Huang, X.; Chen, B.; Zhou, M. HNRNPA2B1 regulates the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells through the ERK/snail signaling pathway. Cancer Cell. Int. 2017, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, D.; He, J.; Zhou, H.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Du, F.; Gong, A.; et al. YTH domain family 2 orchestrates epithelial-mesenchymal transition/proliferation dichotomy in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 2259–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, L.; Sun, H.; Kong, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhou, M. The Lncrna-TUG1/EZH2 Axis promotes pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, migration and EMT phenotype formation through sponging Mir-382. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 42, 2145–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K.; Gong, L.; Yang, Q.; Huang, X.; Hong, C.; Ding, M.; Yang, H. Linc-DYNC2H1-4 promotes EMT and CSC phenotypes by acting as a sponge of miR-145 in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, Z.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, K.; Li, X. MicroRNA-23a promotes pancreatic cancer metastasis by targeting epithelial splicing regulator protein 1. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 82854–82871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wen, C.; Huo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhan, Q.; Cheng, D.; Chen, H.; Deng, X.; Peng, C.; et al. Long noncoding RNA NORAD, a novel competing endogenous RNA, enhances the hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition to promote metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Nong, K.; Zhu, H.; Wang, W.; Huang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Ai, K. H19 promotes pancreatic cancer metastasis by derepressing let-7’s suppression on its target HMGA2-mediated EMT. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 9163–9169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, H.X.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, J.W.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, J.K.; Han, H.F.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.S.; Hu, S.Y. LincRNA-ROR promotes invasion, metastasis and tumor growth in pancreatic cancer through activating ZEB1 pathway. Cancer Lett. 2016, 374, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Li, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, G.; Liu, H.; Kong, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Tian, F.; et al. MiR-361-3p regulates ERK1/2-induced EMT via DUSP2 mRNA degradation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Wang, C.; Zhang, P.; You, S. Emodin inhibits pancreatic cancer EMT and invasion by up-regulating microRNA-1271. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 3366–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, E.C.; Camp, E.R.; Wang, C.; Watson, P.M.; Watson, D.K.; Cole, D.J. The CaSm (LSm1) oncogene promotes transformation, chemoresistance and metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Takano, S.; Yoshitomi, H.; Nishino, H.; Kagawa, S.; Shimizu, H.; Furukawa, K.; Miyazaki, M.; Ohtsuka, M. Metadherin promotes metastasis by supporting putative cancer stem cell properties and epithelial plasticity in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 66098–66111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fabregat, A.; Jupe, S.; Matthews, L.; Sidiropoulos, K.; Gillespie, M.; Garapati, P.; Haw, R.; Jassal, B.; Korninger, F.; May, B.; et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D649–D655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelder, T.; Pico, A.R.; Hanspers, K.; van Iersel, M.P.; Evelo, C.; Conklin, B.R. Mining biological pathways using WikiPathways web services. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresch, R.; Mueller, S.; Veltkamp, C.; Ollinger, R.; Friedrich, M.; Heid, I.; Steiger, K.; Weber, J.; Engleitner, T.; Barenboim, M.; et al. Multiplexed pancreatic genome engineering and cancer induction by transfection-based CRISPR/Cas9 delivery in mice. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Cell Line | Target | EMT Regulation (Direct or Indirect Observation) | KD/KO/Over-expression | Pathway/Mechanism | Functional Assay | Human Prognostic Association | EMT Activator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BxPC-3 | DKK3 | Negative, Direct | Over-expression | DKK3 is overexpressed in tumour and is antagonist of WNT ligand activity, preventing nuclear translocation of β-catenin and EMP under hypoxia | Transwell assays, chemo-resistance, IHC in 75 matched PDAC v normal samples, xenograft growth | Not performed | Hypoxia | [111] |

| ASPC-1, PANC-1 | IGFBP2 | Positive, Direct | siRNA/Over-expression | IGFBP2 activated NF-κB through PI3K/AKT/IKK, inhibited by PTEN | WB, Transwell assays, orthotopic growth, IHC in 80 patient PDAC and lymph node samples | Survival and lymph node metastasis | - | [106] |

| PANC-1 | LTB4 | Positive, Direct | siRNA | LTB4 induced EMT through receptor BLT2 and ERK1/2 activation | WB, Transwell assays | Not performed | LTB4 | [112] |

| Patu8988, PANC-1 | DMKN | Positive, Indirect | shRNA | Knockdown reduced p-STAT3 and EMT increased ERK1/2, AKT | Proliferation, Transwell assays, Xenograft, IHC in 44 patient PDAC tumours | Correlated with T stage | - | [113] |

| PANC-1 | LGALS1 | Positive, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | LGALS1 IHC expression correlated with MMP9 and Vimentin in PDAC. PSC LGALS1 promoted cancer cell EMT and activation of NF-κB | Xenograft, Proliferation, Invasion, IHC in 66 PDAC tumours | Not performed | [114] | |

| BxPC-3, CFPAC | SEMA3C | Positive, Indirect | shRNA/Over-expression | SEMA3C knockdown suppressed EMT and tumourigenesis, and activation of ERK1/2 signaling | Proliferation, migration, Scratch wound, Xenograft, IHC in 118 PDAC tumours | Stage, survival, recurrence | [115] | |

| Capan-1 | FUT3 | Positive, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | FUT3 knockdown impeded proliferation, migration, tumour growth and TGFβ induced EMT | Proliferation, Scratch wound, Transwell assays, Xenograft | Not performed | TGFβ | [116] |

| PANC-1, MIAPaCa-2, Capan-2 | MIF/ NR3C2 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/Over-expression | MIF induces miR-301b, targeting NR3C2, inducing EMT and chemo sensitivity | PDAC transcriptome by array, IHC of 173 PDAC, Proliferation, Colony formation, Transwell assays, chemo-resistance | NR3C2 inversely prognostic by RNA and IHC | - | [117] |

| PANC-1, BxPC-3 | WNT5A | Positive, Direct | siRNA, Over-expression | Wnt5a expression induced EMT and invasion and was elevated in PDAC by IHC | Scratch wound, Transwell assays, WB, orthotopic growth, IHC of 134 PDAC v normal | No | - | [118] |

| PANC-1 | LCN2 | Negative, Indirect | Over-expression | LCN2 expression correlated with better survival and lower EMT state | IHC of 60 PDAC tumours, Transwell assays | Protective by IHC | - | [119] |

| MIAPaca-2, BxPC-3, SUIT-2 | NOV | Positive, Indirect | shRNA/Over-expression | NOV expression high in PDAC by IHC, and induced EMT phenotypes in vitro/in vivo | Colony formation, soft agar, Proliferation, Transwell assays, in vivo metastasis | Not performed | - | [120] |

| PANC-1, BxPC-3 | CCL18 | Positive, Direct | CCL18 expressed in mesenchymal and cancer cells, and induced EMT | WB, Transwell assays, IHC of 62 PDAC tumours, serum ELISA from PDAC patients | Survival | - | [121] | |

| PANC-1, BxPC-3 | TUFT1 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/Over-expression | TUFT1 expression correlated with T stage and lymph node metastasis by IHC, RNA expression correlated with HIF1a, SNAI1 and VIM | WB, Proliferation, scratch wound, Transwell assays, Xenograft, IHC of 63 PDAC tumours | Yes in TCGA by RNA | [122] | |

| SW1990, ASPC-1 | OLR1 | Positive, Direct | siRNA/Over-expression | OLR1 overexpressed in tumours and correlates with metastasis and poor survival, overexpression induced EMT | Transwell assays, scratch wound, Proliferation/apoptosis, IHC of 98 PDAC tumours | Yes survival by IHC and TCGA | - | [123] |

| MIAPaCa-2, PANC-1, ASPC-1, BxPC-3 | LOXL2 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/Over-expression | LOXL2 IHC expression correlated with recurrence, depth of invasion and poor survival, and enhanced EMT in vitro | Transwell assays, IHC of 80 PDAC tumours | Yes by IHC | - | [124] |

| PANC-1, PK9 | TFF1 | Negative, Direct | siRNA | TFF only expressed in PanIN and intraductal neoplasia, not normal or invasive PDAC, knockdown activated EMT, loss of TFF in GEMM drove PanIN, PDAC and CAF infiltration | Transwell Invasion, Scratch wound, KC GEMM, IHC on small number of samples | Not performed | - | [125] |

| Cell Line | Target | EMT Regulation | KD/KO/Over-expression | Pathway/Mechanism | Functional Assay | Prognostic Association | EMT Activator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L3.6pl | VEGFR1 activation | Positive, Direct | RTK VEGFR-1 activation induced SNAI1/2, TWIST | E-cadherin/b-catenin localization/WB | Not performed | VEGF | [95] | |

| PANC-1, MiaPaCa-2 | HTR1B, HTR1D | Positive, Indirect | siRNA | 5-HT receptor knockdown reduced uPAR and Src/FAK signaling and EMT | Scratch wound, Transwell, Colony formation | Not performed | - | [126] |

| PANC-1 HPAC | IGF1R | Positive, Indirect | siRNA | IGF1R overexpressed in PDAC by IHC, silencing inhibits AKT/PI3K, MAPK, JAK/STAT signaling pathways | Transwell assays, soft agar, Proliferation, apoptosis, IHC of TMA | Not performed | - | [127] |

| L3.6pl, BxPC-3 | DDR1 | Positive, Direct | siRNA/ Over-expression | DDR1 expression correlates with CHD2 expression by IHC, DDR1-b signals through SHC1 adapter to PYK2 to induce CDH2 | Invasion, IHC of PDAC TMA | Not performed | COL1A | [97] |

| PANC-1 | SMO | Positive, Indirect | siRNA | Hedgehog activated in tumourspheres, SMO knockdown inhibited CSC/EMT features properties | Proliferation, sphere formation, Transwell assays, Xenograft | Not performed | - | [128] |

| PANC-1, BxPC-3 | EPHA4 | Positive, Direct | siRNA | EPHA4 knockdown suppressed EMT, MMP2 activity | Gelatin zymography, Transwell assays, scratch wound, WB | Not performed | - | [129] |

| CFPAC-1, AsPC-1 | ITGB4 | Positive, Direct | siRNA/Over-expression | ITGB4 IHC expression correlated with T stage, knockdown inhibited EMP | Transwell assays, WB, IHC of 134 PDAC tumours | Survival lymph node metastasis by IHC | TGFβ | [107] |

| PANC-1, MiaPaCa2, Capan2 | F2R | Positive, Indirect | shRNA | F2R (PAR1) expression associated with mesenchymal gene signature | Xenograft, Scratch wound | Not performed | - | [130] |

| Cell Line | Target | EMT Regulation | KD/KO/Over-expression | Pathway/Mechanism | Functional Assay | Prognostic Association | EMT Activator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANC-1 | CDCP1 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA | CDCP1 expression high in PDAC, induced by BMP4/ERK signaling, and knockdown inhibited EMT phenotypes | Scratch wound, Transwell, spheroid formation, chemo-resistance, IHC on 42 PDAC tumours | Not performed | - | [131] |

| Colo-357, Capan-1 | MUC16 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA, CRISPR/Cas9 | MUC16 knockdown decreased FAK mediated AKT/ERK/MAPK activation, and EMT | Proliferation, migration, Colony formation, Xenograft | Not performed | - | [132] |

| MiaPaCa2 | ANXA1 | Positive, Indirect | CRISPR | ANXA1 KO downregulated miR196a, effected cell motility and liver metastases in vivo | Scratch wound, Transwell migration, Invasion, Xenograft | Not performed | [133,134] | |

| CFPAC-1, PANC-1 | CEACAM6 | Positive, Direct | shRNA, Over-expression | CEACAM6, regulated by miR-29a/b/c, required for EMT | Transwell assays, Xenograft, WB, IHC in 99 PDAC tumours | Lymph node metastasis | - | [108] |

| SUIT-2, CAPAN-2 | TM4SF1 | Negative, Indirect | siRNA | TM4SF1 IHC expression protective, knockdown induced migration and decreased E-cadherin | Transwell assays, IHC in 74 PDAC tumours | Yes inversely prognostic by IHC | TGFβ | [135] |

| PANC-1, SW1990 | DPP4 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/ Over-expression | DPP4 (CD26) knockdown suppressed EMT, in vivo growth | Proliferation, Transwell assays, Xenograft, WB | Not performed | - | [136] |

| PANC-1, AsPC-1 | SLC39A4 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/ overexpression | SLC39A4 (ZIP4) IHC expression correlated with ZEB1 and EMT, increasing FAK and paxillin phosphorylation | Xenograft, Scratch wound, Transwell migration, Invasion, IHC of 72 paired PDAC v normal | Not performed | - | [137] |

| Cell Line | Target | EMT Regulation | KD/KO/Over-expression | Pathway/Mechanism | Functional Assay | Prognostic Association | EMT Activator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANC-1, CFPAC-1 | WASF3 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA, | WASF3 (WAVE3) knockdown suppressed PDK2, downregulating PBK/AKT pathway and EMT | Proliferation, migration, Invasion, Scratch wound, IHC of 87 paired PDAC v normal | Lymph node metastasis | - | [138] |

| PANC-1, AsPC-1, MiaPaCa-2 | NES | Positive, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | NES (Nestin) required for EMT and induced by TGFβ in positive feedback loop promoting p-smad2 | Xenograft, Transwell assays, IHC of GEMM | Not performed | TGFβ | [139,140] |

| HPAF-II, PANC-04.03 PANC-1 | DNM2 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA, Over-expression | Upregulated by IHC in PDAC, DNM2/VAV1 interaction required for RAC-1 induced lamellipodia formation | Transwell assays, lamellipodia formation, xenograft, IHC of 85 PDAC tumours | Not performed | EGF (HPAF-II) | [141,142] |

| SUIT-2 | RAB5A | Positive, Indirect | siRNA | RAB5 IHC expression correlated with invasion and CDH1, aids TGFβR endocytosis, stimulates FA turnover, prognostic in PDAC, breast, ovarian | Morphology, Proliferation, Transwell assays, IHC of 111 PDAC tumours | Survival IHC | - | [143] |

| Cell Line | Target | EMT Regulation | KD/KO/Over-expression | Pathway/Mechanism | Functional Assay | Prognostic Association | EMT Activator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANC-1, MIAPaCa-2 | EEF2K, | Positive, Direct | siRNA/Over-expression | EEF2K promotes EMT through TG2/β1 integrin/SRC/uPAR/MMP2 signaling | Scratch wound, Transwell assays, WB | Not performed | - | [144] |

| Patu8988, PANC-1, BxPC-3, Capan-1 | CDK14 | Positive, Direct | siRNA | Suppression of CDK14 reduced PI3K/AKT activation and EMT | Proliferation, Colony formation, Transwell assays | Not performed | - | [145] |

| HDPE | PRAG1 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/Over-expression | Phosphorylation of PRAG1 found in malignant cells, Over-expression induced JAK1/STAT3 mediated EMT | Transwell assays, phospho-WB | Not performed | - | [146] |

| BxPC-3, PANC-1 | AURKA | Positive, Direct | shRNA | AURKA IHC expression high in PDAC, phosphorylates and stabilizes TWIST1 in positive feedback loop, promoting EMT | Sphere formation, migration, Proliferation, Xenograft, IHC on small PDAC cohort | Not performed | - | [63] |

| PANC-1, ASPC-1 | MAP3K3 | Positive, Direct | CRISPR | MAP3K3 (MEKK3) KO reduced EMT, CSC and migration, and YAP/TAZ transcriptional activity on AXL, DKK1, FosL1, CTGF | Transwell migration Invasion, Proliferation, Xenograft, ChIP | Not performed | - | [147] |

| PANC-1, COLO357 | RAC1 | Negative, Direct | siRNA/Over-expression | RAC1b inhibits canonical and non-canonical TGFβ signaling, effecting MKK6-p38 and MEK-ERK-MAPK EMT activation | Migration, qPCR | Not performed | TGFβ | [90,148] |

| HPAF-II, CAPAN-2 | PTPN11 | Positive, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | PTPN11 (SHP2) activity enhances the effect of EGF on TGFβ induced EMT, resulting in more complete EMT | Cell scatter, scratch wound, WB | Not performed | TGFβ/EGF | [100] |

| Cell Line | Target | EMT Regulation | KD/KO/Over-expression | Pathway/Mechanism | Functional Assay | Prognostic Association | EMT Activator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANC-1 | USP22 | Positive, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | USP22 expression correlated with Ezrin and FAK phosphorylation and EMT | Scratch wound, Transwell assays, WB | Not performed | - | [149] |

| 779E, 1334 PDCL | EIF5A | Positive, Indirect | shRNA/Over-expression | Mutant KRAS induces EIF5A, stimulating PEAK1 mediated ECM signaling. PEAK1 binds YAP/TAZ driving stem TFs | Sphere formation, IP, WB | Not performed | - | [150] |

| AsPC-1, PANC-1 | EIF4E | Negative, Indirect | siRNA | Knockdown of MNK effector, EIF4E, induced ZEB1 through repression of miR-200c, miR-141, MNK inhibitors induce MET | Collagen 3D, qPCR | Not performed | - | [94] |

| BxPC-3 | RGCC | Positive, Direct | siRNA | RGCC regulated by HIF1α and required for hypoxia induced EMT | qPCR, WB | Not performed | hypoxia | [151] |

| PANC-1 MIA PaCa-2 | SET | Positive, Direct | shRNA/ Over-expression | SET over-expression activated Rac1/JNK/c-Jun pathway and decreased PP2A activity, N-cadherin and EMT TFs up | Transwell assays, Colony formation, Xenograft tumour growth and liver metastases | Not performed | - | [152] |

| MiaPaCa2, SW1990, PANC-1, CFPAC1 | GPX1 | Negative, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | GPX1 IHC expression lower in PDAC, silencing induced EMT and gemcitabine resistance through ROS activated PI3K/Akt/GSK3B/SNAIL, Over-expression sensitized in vivo | Transwell migration, chemo-resistance, Xenografts, IHC of 281 PDAC tumours, and 42 paired PDAC v normal | Yes inversely prognostic by IHC | [153] | |

| BxPC-3, PANC-1, MiaPaCa2, PSN1 | HDAC1 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA | HDAC IHC expression and activity correlated with EMT phenotype | IHC, Transwell Invasion, IHC of 103 PDAC tumours | Survival by IHC | - | [154] |

| PANC-1 BxPC-3 | Class I HDAC | Positive, Indirect | 4SC-202 small inhibitor | HDACi (inhibition) blocked TGFβ induced EMT in PANC-1, requiring BRD4 and MYC for effect of HDACi | Migration, sphere formation, Xenograft | Not performed | TGFβ (PANC-1) | [155] |

| CFPAC-1, L3.7-2 | PAFAH1B2 | Positive, Direct | siRNA/Over-expression | PAFAH1B2 IHC expression higher in PDAC, HIF1a expression regulated PAFAH1B2 via direct promoter binding | Transwell migration, Invasion, orthotopic Xenograft/ liver metastases, HIF1a/PAFAH1B2 co-localization in PDAC, IHC of 124 PDAC tumours and 70 normal | Survival by IHC and TCGA | hypoxia | [156] |

| PANC-1, MIAPaCa-2 | KDM4B | Positive, Direct | siRNA | KDM4B IHC expression correlated with ZEB1 in PDAC, knockdown inhibited TGFβ induced EMT in PANC-1 by regulating ZEB1 methylation | CHIP, scratch wound, Transwell assays, IHC of 49 PDAC tumours | Not performed | TGFβ | [157] |

| HPAC, BxPC-3, Colo357 PANC-1, MiaPaCa-2 | SMURF2 | Negative, Direct | SMURF negative regulator of TGFβ induced EMT, suppressed by miR-15b | Scratch wound, Transwell assays, WB | Not performed | TGFβ | [158] | |

| CAPAN-1 PANC-1 | CUL4B | Positive, Direct | miRNA | CUL4B IHC expression higher in PDAC, regulated by miR -300, required for Wnt/β-catenin induced EMP | qPCR, Transwell assays, Xenograft, IHC of 110 PDAC v normal | Not performed | - | [159] |

| PANC-1 | KMT5C | Positive, Direct | siRNA | KMT5C (SUV420H2) expression higher in PanIN and PDAC, methylates H4K20me3,suppresses epithelial drivers FOXA1, OVOL2, OVOL2 | Transwell assays, chemo-resistance, sphere formation, | Not performed | - | [160] |

| PANC-1 | NOX4 | Positive, Direct | siRNA | NOX4 IHC expression elevated in PDAC, aids ROS generation and TGFβ induced EMT | Transwell assays, WB | Not performed | TGFβ | [161] |

| BxPC-3 | PAWR | Negative, Indirect | siRNA, Over-expression | PAWR (PAR4) suppressed in cisplatin resistant EMT cells, required PI3K/AKT signaling | Transwell assays, Proliferation, WB, Xenograft | Not performed | - | [162] |

| BxPC-3 | PPM1H | Negative, Indirect | siRNA | PPM1H expression decreased by TGFβ/BMP2 treatment, knockdown induced EMT | Proliferation, Transwell assays, WB, apoptosis | Not performed | TGFβ, BMP2 | [98] |

| PANC-1 | HMGN5 | Positive, Indirect | shRNA | HMNG5 silencing reduced Wnt expression | Xenograft, Transwell migration Invasion, WB, | Not performed | - | [163] |

| PANC-1 | GOLM1 | Positive, Direct | siRNA/ overexpression | GOLM1 (GP73) overexpression induced EMT and correlated with human metastasis and Xenograft growth | Xenograft, Transwell migration Invasion, Scratch wound, WB | Not performed | - | [164] |

| Cell Line | Target | EMT Regulation | KD/KO/Over-expression | Pathway/Mechanism | Functional Assay | Prognostic Association | EMT Activator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaTu 8988T, AsPC-1 | GLI1 | Positive, Direct | siRNA | GLI1 component of HH signaling, induced EMT by TNF-α/IL-1β, mediated through NF-κB pathway | Transwell assays, WB | Not performed | TNF-α/IL-1β | [96,165,166,167,168] |

| Colo-357, L3.7 | FOXM1 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/Over-expression | FOXM1c activates uPAR promoter directly, inducing EMT | Scratch wound, Transwell migration, IHC of PDAC TMA v normal | Elevated in metastatic PDAC | - | [169] |

| BxPC-3, ASPC-1, PANC-1 | TAZ | Negative, Direct | shRNA, Over-expression | TAZ required for EMT through TEA/ATTS TFs, activation correlates with suppression of NF2 | Colony formation, Xenograft, Transwell assays, IHC of 57 PDAC v normal | Correlated with PDAC differentiation | - | [170] |

| PANC-1, CAPAN-1 | YAP | Positive, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | YAP expression associated with activation of AKT cascade and EMT | Transwell assays, chemo-resistance, WB | Not performed | - | [171] |

| PANC-1, BxPC-3 | HSF1 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA | p-HSF1 IHC elevated in PDAC, promotes invasion and is downregulated by p-AMPK | Transwell assays, scratch, WB, GEMM | Not performed | - | [172] |

| HPAC, MiaPaCa2 | FOXC1 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/Over-expression | IGFR1 positively regulates FOXC1, activating PI3K/Akt/ERK, promoting migration, and EMT, and tumour growth | Xenograft, Transwell migration Invasion, soft agar | Not performed | IGF | [173] |

| PANC-1, SW1990 | BHLHA15, Direct | Negative, Direct | Over-expression | BHLHA15 (MIST1) Over-expression suppressed tumour growth & metastases. Caused MET by suppressing SNAIL indirectly | Transwell migration, Invasion, Xenograft and liver met | Not performed | - | [174] |

| PANC-1 | KLF8, Indirect | Positive, Direct | siRNA, Over-expression | KLF8 IHC elevated in PDAC, directly induces FHL2 transcription via promoter binding | WB, Invasion | Not performed | - | [175] |

| GEMM | P73, Direct | Negative, Direct | GEMM | P73 deficiency led to stromal deposition and EMT in PDAC tumours, decreased BGN secretion, required for tumour suppressive functions of TGFβ | GEMM, Transwell assays | Not performed | - | [176] |

| GEMM | PRRX1 | Positive, Direct | Overexpression | PRRX1 a/b have discrete functions in MET/EMT, knockdown suppresses tumour growth and EMT | GEMM tumour model, Xenograft | Not performed | - | [177] |

| Capan-2 | TRIM28 | Positive, Indirect | Overexpression | TRIM28 Overexpression drove EMT and Invasion, correlated with T stage | Transwell assays, WB, Xenograft, IHC of 91 PDAC | Lymph node metastasis and survival | - | [178] |

| PANC-1 | ETS1 | Positive, Direct | shRNA | ETS1 knockdown epithelialized PANC-1 cells | Scratch wound, adhesion, qPCR for EMT markers | Not performed | - | [179] |

| HDPE, COLO-357 | NFE2L2 | Positive, Direct | siRNA/Over-expression | NFE2L2 activation enhanced TGFβ induced EMT in both premalignant and malignant cells | Scratch wound, Transwell assays, WB, qPCR | Not performed | TGFβ | [180] |

| PANC-1, HPAF-II | PDX1 | Positive, Indirect | shRNA, GEMM | PDX1 has dual roles in premalignant and transformed cells. PDX1 expression is reduced in tumours and EMT | Colony formation, GEMMs, IHC of 183 PDAC | Inversely prognostic for survival | TGFβ (PANC-1), HGF (HPAF-II) | [181] |

| PANC-1 | BCL9L | Positive, Direct | siRNA/Over-expression | BCL9L knockdown prevented EMT and inhibited in vivo growth | Proliferation, Transwell assays, Xenograft | Not performed | TGFβ | [182] |

| GEMM | ETV1 | Positive, Direct | Overexpression | ETV1 induces SPARC, required for tumour growth and metastasis in vivo, EMT in vitro | Xenograft, Invasion | Not performed | - | [183] |

| ASPC-1, SW1990 | EPAS1 | Positive, Direct | siRNA | EPAS1 (HIF2α) IHC expression high in PDAC, and knockdown inhibited EMT | CHIP, Transwell assays, IHC of 70 PDAC | Lymph node metastasis, differentiation | - | [184] |

| PANC-1 BxPC-3 | SIX1 | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/shRNA | SIX1 IHC expression elevated in PDAC, knockdown reduced migration and tumour size | Migration, EMT markers, PANC-1 Xenograft, CD44-/CD24+, IHC of 139 PDAC | No | - | [185] |

| Cfpac-1 | GRHL2 | Negative, Direct | siRNA | GRHL2 IHC expression elevated in normal duct and liver metastases, drives epithelial phenotype. | Proliferation, EMT markers, Colony and sphere formation, drug resistance, IHC of 155 PDAC | No | - | [186] |

| PaTu8988S | GATA6 | Negative, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | GATA6 IHC expression low in PDAC, Silencing induced EMT | chemo-resistance, IF, Invasion, Xenograft, IHC of 58 PDAC | Inversely prognostic for survival | - | [187] |

| Cell Line | Target | EMT Regulation | KD/KO/Over-expression | Pathway/Mechanism | Functional Assay | Prognostic Association | EMT Activator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miapaca-2, PANC-1, Patu-8988 | HNRNPA2B1 | Positive, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | Knockdown epithelialized cells, Over-expression drove EMT through ERK/SNAI1 pathway | Cell viability, Transwell assays, PANC-1 Xenograft, EMT markers | Not performed | - | [188] |

| SW1990, BxPC-3 | YTHDF2 | Negative, Direct | shRNA | Knockdown reduced p-AKT, p-GSK-3b, promoted EMT, YAP knockdown reversed effect | Proliferation, Colony formation, Invasion, adhesion | Not performed | - | [189] |

| Panc-1, Patu8988 | Lnc TUG1 | Positive, Direct | shRNA | Lnc TUG1 sponges miR-382, preventing repression of ezh2 | Colony formation, Transwell assays, WB | Not performed | - | [190] |

| Gemcitabine resistant BxPC-3 | DYNC2H1-4 | Positive, Direct | siRNA | Lnc DYNC2H1-4 sponges miR-145, upregulating ZEB1, MMP3 and other CSC markers | Transwell assays, CSC markers, Xenograft | Not performed | - | [191] |

| ASPC-1, BxPC-3, PANC-1 | miR-23 | Positive, Direct | miRNAs | miR -23 promotes EMT by regulating ESRP1, miR-23 required for TGFβ induced EMT | WB, Transwell assays, Xenograft, qPCR of 52 paired PDAC tumour v normal | Survival by RNA | TGFβ | [192] |

| SW1990, PANC-1, BxPC-3, CAPAN-1 | NORAD | Positive, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | Lnc NORAD acts as ceRNA of miR-125a-3p, enhancing RHOa and EMT | Scratch wound, Transwell assays, Xenograft | Not performed | Hypoxia | [193] |

| Panc-1 | Lnc H19 | Positive, Direct | siRNA | H19 antagonised LET-7, inducing HMGA-2 mediated EMT | Transwell assays, scratch wound, WB | Not performed | - | [194] |

| ASPC-1, BxPC-3 | LncRNA-ROR | Positive, Direct | shRNA/Over-expression | LncRNA-ROR expression induces ZEB1 and EMT | Scratch wound, Transwell assays, Xenograft | Not performed | - | [195] |

| PANC-1, BxPC-3, COLO357 | miR-100, miR -125b | Positive, Indirect | siRNA/CRISPR/Over-expression | TGFβ induced lnc-miR100HG, which codes for tumourigenic miR 100, miR125b and LET-7a. LIN28B also induced by TGFβ, suppresses LET-7a activity | miR Over-expression, Xenograft, Scratch wound, sphere formation, RNAseq, RIPseq | Survival by RNA | TGFβ | [109] |

| BxPC-3, PANC-1, CFPAC-1, SW1990 | miR-361-3p | Positive, Direct | Over-expression | miR-361-3p downregulates DUSP2, preventing inactivation of ERK1/2 | Orthotopic metastasis, Transwell assays | Survival by RNA | - | [196] |

| Sw1990 | miR-1271 | Negative, Direct | miR Mimics, Inhibitors | miR -1271 inhibited EMT and migration | Proliferation, Transwell migration invasion, xenograft | Not performed | - | [197] |

| Panc-1 | LSM1 | Positive, Indirect | Over-expression | Lsm1 (CaSm) induction induced EMT and proliferation, effecting apoptotic and metastasis gene expression | Proliferation, anoikis, Transwell assays, chemo-resistance, xenograft | Not performed | - | [198] |

| KPCY | MTDH | Positive, Indirect | siRNA | MTDH expression promoted CSC and metastasis, high cytoplasmic expression by IHC | Spheroid formation, orthotopic and metastatic xenograft models, IHC of 134 PDAC | Survival | - | [199] |

| ASPC-1, HS766t, BxPC-3 | LIN28B | Positive, Direct | shRNA | LIN28B IHC expression high in PDAC, suppression inhibited proliferation and EMT | Colony formation, Proliferation, migration, IHC of 185 PDAC tumours | Survival, stage, metastasis | - | [110] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monkman, J.H.; Thompson, E.W.; Nagaraj, S.H. Targeting Epithelial Mesenchymal Plasticity in Pancreatic Cancer: A Compendium of Preclinical Discovery in a Heterogeneous Disease. Cancers 2019, 11, 1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11111745

Monkman JH, Thompson EW, Nagaraj SH. Targeting Epithelial Mesenchymal Plasticity in Pancreatic Cancer: A Compendium of Preclinical Discovery in a Heterogeneous Disease. Cancers. 2019; 11(11):1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11111745

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonkman, James H., Erik W. Thompson, and Shivashankar H. Nagaraj. 2019. "Targeting Epithelial Mesenchymal Plasticity in Pancreatic Cancer: A Compendium of Preclinical Discovery in a Heterogeneous Disease" Cancers 11, no. 11: 1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11111745