Next-Generation Service Delivery: A Scoping Review of Patient Outcomes Associated with Alternative Models of Genetic Counseling and Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

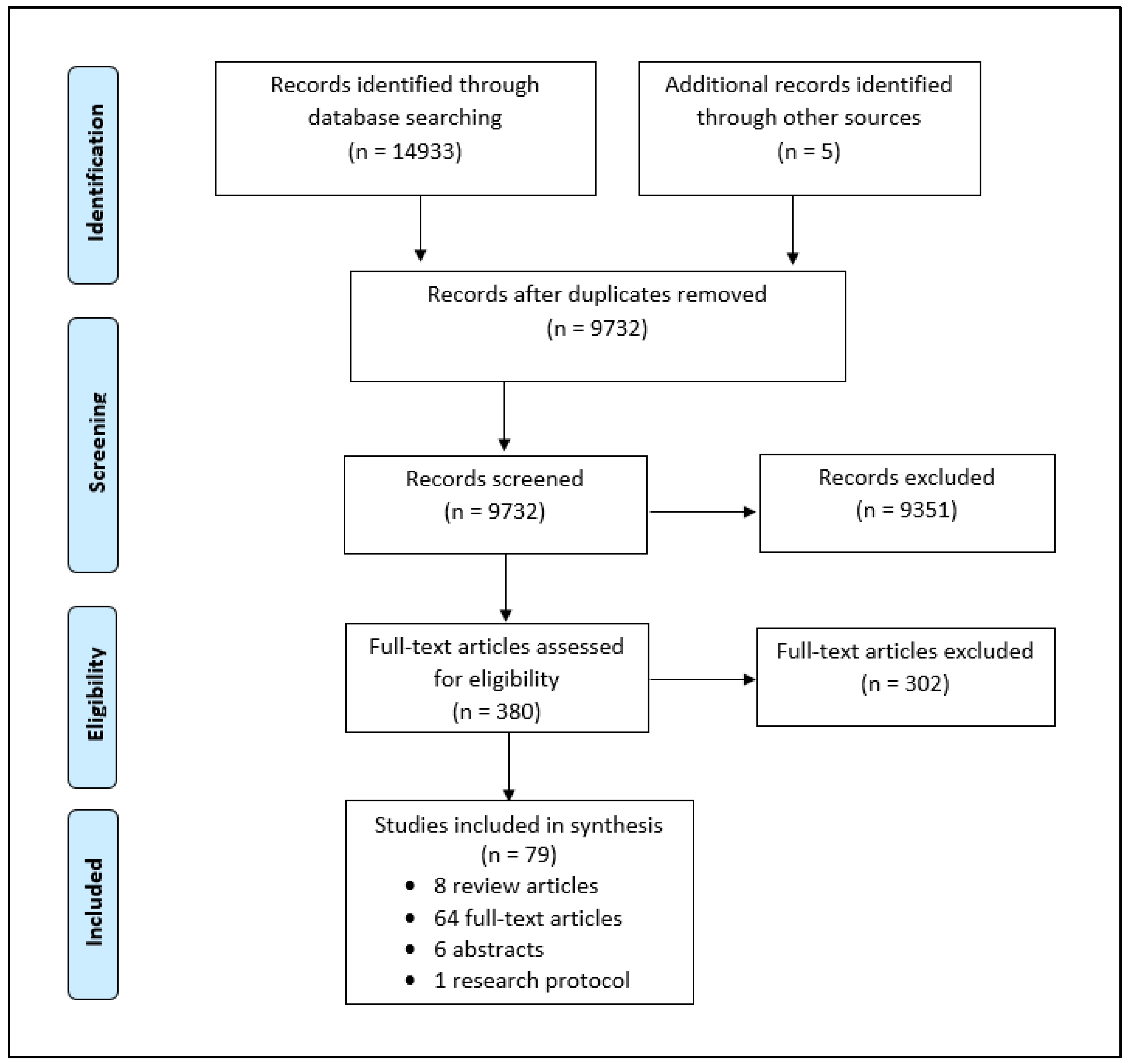

2. Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Charting the Data and Reporting Results

3. Results

3.1. Telephone Genetic Counseling Models

3.2. Telegenetic Genetic Counseling Models

3.3. Group Genetic Counseling Models

3.4. Embedded Genetic Counseling Models

3.5. “Mainstreaming” Genetic Testing Models

3.6. Direct Genetic Testing Models

3.7. Tumor-First Genetic Testing Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Alternative GC Models

4.2. Alternative GT Models

4.3. Future Directions

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Medline Search Strategy

| 1 | exp Neoplasms/ |

| 2 | neoplas*.mp,kw. |

| 3 | paraneoplas*.mp,kw |

| 4 | cancer*.mp,kw. |

| 5 | tumo?r*.mp,kw. |

| 6 | onco*.mp,kw. |

| 7 | metast*.mp,kw. |

| 8 | malignan*.mp,kw. |

| 9 | adenocarcin*.mp,kw. |

| 10 | carcin*.mp,kw. |

| 11 | HBOC.mp,kw. |

| 12 | HNPCC.mp,kw. |

| 13 | lynch*.mp,kw. |

| 14 | or/1-13 |

| 15 | exp Genetic Services/ |

| 16 | Genetic Counseling/ |

| 17 | Genetic Testing/ |

| 18 | Genes, Neoplasm/ |

| 19 | Germ-Line Mutation/ |

| 20 | (genetic? adj2 service?).mp,kw. |

| 21 | (genetic? adj2 counsel*).mp,kw. |

| 22 | (genetic? adj2 screen*).mp,kw. |

| 23 | (genetic? adj2 test*).mp,kw. |

| 24 | (somatic adj2 screen*).mp,kw. |

| 25 | (somatic adj2 test*).mp,kw. |

| 26 | (germline? adj2 screen*).mp,kw. |

| 27 | (germline? adj2 test*).mp,kw. |

| 28 | (profiling* adj2 screen*).mp,kw. |

| 29 | (molecular* adj2 screen*).mp,kw. |

| 30 | or/15-29 |

| 31 | (universal* adj3 screen*).mp,kw. |

| 32 | 14 and 31 |

| 33 | “Outcome and Process Assessment (Health Care)”/ |

| 34 | “Outcome Assessment (Health Care)”/ |

| 35 | exp Patient Outcome Assessment/ |

| 36 | Patient Reported Outcome Measures/ |

| 37 | “Early Detection of Cancer”/ |

| 38 | Incidental Findings/ |

| 39 | Psychological Trauma/ |

| 40 | exp Stress Psychological/ |

| 41 | Stress Disorders, Traumatic/ |

| 42 | Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic/ |

| 43 | Stress Disorders, Traumatic, Acute/ |

| 44 | exp Patient Satisfaction/ |

| 45 | Patient Preference/ |

| 46 | Patient Access to Records/ |

| 47 | (patient? adj3 outcome?).mp,kw. |

| 48 | (clinc* adj3 outcome?).mp,kw. |

| 49 | (counsel* adj3 outcome?).mp,kw. |

| 50 | (earl* adj3 detect*).mp,kw. |

| 51 | (profiling* adj2 detect*).mp,kw. |

| 52 | (incidental* adj2 finding?).mp,kw. |

| 53 | (incidental* adj2 germline?).mp,kw. |

| 54 | (psycho* adj3 trauma*).mp,kw. |

| 55 | (psycho* adj3 measur*).mp,kw. |

| 56 | (psycho* adj3 outcome?).mp,kw. |

| 57 | (psycho* adj3 function*).mp,kw. |

| 58 | (psycho* adj3 impact*).mp,kw. |

| 59 | (psycho* adj3 effect?).mp,kw. |

| 60 | (psycho* adj3 distress*).mp,kw. |

| 61 | (patient? adj2 satisfact*).mp,kw. |

| 62 | (patient? adj2 prefer*).mp,kw. |

| 63 | access*.mp,kw. |

| 64 | mainstream*.mp,kw. |

| 65 | main-stream*.mp,kw. |

| 66 | universal*.mp,kw. |

| 67 | model?.mp,kw. |

| 68 | or/33-67 |

| 69 | 14 and 30 and 68 |

| 70 | 32 or 69 |

| 71 | exp animals/not (exp animals/and exp humans/) |

| 72 | 70 not 71 |

| 73 | limit 72 to “all child (0 to 18 years)” |

| 74 | limit 72 to “all adult (19 plus years)” |

| 75 | 73 not 74 |

| 76 | 72 not 75 |

| 77 | limit 76 to yr = “2007-Current” |

| 78 | limit 77 to English language |

| 79 | remove duplicates from 78 |

Appendix B. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|

|

References

- Evans, D.G.; Barwell, J.; Eccles, D.M.; Collins, A.; Izatt, L.; Jacobs, C.; Donaldson, A.; Brady, A.F.; Cuthbert, A.; Harrison, R.; et al. The Angelina Jolie effect: How high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphael, J.; Verma, S.; Hewitt, P.; Eisen, A. The Impact of Angelina Jolie (AJ)’s Story on Genetic Referral and Testing at an Academic Cancer Centre in Canada. J. Genet. Couns. 2016, 25, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchtel, K.M.; Vogel Postula, K.J.; Weiss, S.; Williams, C.; Pineda, M.; Weissman, S.M. FDA Approval of PARP Inhibitors and the Impact on Genetic Counseling and Genetic Testing Practices. J. Genet. Couns. 2018, 27, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Royer, R.; Li, S.; McLaughlin, J.R.; Rosen, B.; Risch, H.A.; Fan, I.; Bradley, L.; Shaw, P.A.; Narod, S.A. Frequencies of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among 1,342 unselected patients with invasive ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 121, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harter, P.; Hauke, J.; Heitz, F.; Reuss, A.; Kommoss, S.; Marmé, F.; Heimbach, A.; Prieske, K.; Richters, L.; Burges, A.; et al. Prevalence of deleterious germline variants in risk genes including BRCA1/2 in consecutive ovarian cancer patients (AGO-TR-1). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norquist, B.M.; Harrell, M.I.; Brady, M.F.; Walsh, T.; Lee, M.K.; Gulsuner, S.; Bernards, S.S.; Casadei, S.; Yi, Q.; Burger, R.A.; et al. Inherited Mutations in Women with Ovarian Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demsky, R.; McCuaig, J.; Maganti, M.; Murphy, K.J.; Rosen, B.; Armel, S.R. Keeping it simple: Genetics referrals for all invasive serous ovarian cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 130, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, J.; Panabaker, K.; Leonard, S.; Ainsworth, P.; Elit, L.; Shariff, S.Z. Genetics Consultation Rates Following a Diagnosis of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma in the Canadian Province of Ontario. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childers, C.P.; Childers, K.K.; Maggard-Gibbons, M.; Macinko, J. National Estimates of Genetic Testing in Women With a History of Breast or Ovarian Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3800–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskins, P.J.; Gotlieb, W.H. Missed therapeutic and prevention opportunities in women with BRCA-mutated epithelial ovarian cancer and their families due to low referral rates for genetic counseling and BRCA testing: A review of the literature. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, L.M.; Pothuri, B.; Swisher, E.M.; Diaz, J.P.; Buchanan, A.; Witkop, C.T.; Bethan Powell, C.; Smith, E.B.; Robson, M.E.; Boyd, J.; et al. Multi-disciplinary summit on genetics services for women with gynecologic cancers: A Society of Gynecologic Oncology White Paper. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 146, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCuaig, J.M.; Stockley, T.L.; Shaw, P.; Fung-Kee-Fung, M.; Altman, A.D.; Bentley, J.; Bernardini, M.Q.; Cormier, B.; Hirte, H.; Kieser, K.; et al. Evolution of genetic assessment for BRCA-associated gynaecologic malignancies: A Canadian multisociety roadmap. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 55, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samimi, G.; Bernardini, M.Q.; Brody, L.C.; Caga-Anan, C.F.; Campbell, I.G.; Chenevix-Trench, G.; Couch, F.J.; Dean, M.; de Hullu, J.A.; Domchek, S.M.; et al. Traceback: A Proposed Framework to Increase Identification and Genetic Counseling of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers Through Family-Based Outreach. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health. Traceback Testing: Increasing Identification and Genetic Counseling of Mutation Carriers through Family-based Outreach (U01 Clinical Trial Optional). Available online: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-18-616.html (accessed on 24 September 2018).

- Hoskovec, J.M.; Bennett, R.L.; Carey, M.E.; DaVanzo, J.E.; Dougherty, M.; Hahn, S.E.; LeRoy, B.S.; O’Neal, S.; Richardson, J.G.; Wicklund, C.A. Projecting the Supply and Demand for Certified Genetic Counselors: A Workforce Study. J. Genet. Couns. 2018, 27, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.A.; Gustafson, S.L.; Marvin, M.L.; Riley, B.D.; Uhlmann, W.R.; Liebers, S.B.; Rousseau, J.A. Report from the National Society of Genetic Counselors service delivery model task force: A proposal to define models, components, and modes of referral. J. Genet. Couns. 2012, 21, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.A.; Marvin, M.L.; Riley, B.D.; Vig, H.S.; Rousseau, J.A.; Gustafson, S.L. Identification of genetic counseling service delivery models in practice: A report from the NSGC Service Delivery Model Task Force. J. Genet. Couns. 2013, 22, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trepanier, A.M.; Allain, D.C. Models of service delivery for cancer genetic risk assessment and counseling. J. Genet. Couns. 2014, 23, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, A.H.; Rahm, A.K.; Williams, J.L. Alternate Service Delivery Models in Cancer Genetic Counseling: A Mini-Review. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, D.M.; Bazzell, A.F.; Dains, J.E. Comparing Outcomes of Genetic Counseling Options in Breast and Ovarian Cancer: An Integrative Review. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2018, 45, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Kaye, S.; Banerjee, S. Delivering widespread BRCA testing and PARP inhibition to patients with ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogerbrugge, N.; Jongmans, M.C. Finding all BRCA pathogenic mutation carriers: Best practice models. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24 (Suppl. 1), S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlensky, L.; Trepanier, A.M.; Cragun, D.; Lerner, B.; Shannon, K.M.; Zierhut, H. A Rapid Systematic Review of Outcomes Studies in Genetic Counseling. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trepanier, A.M.; Cohen, S.A.; Allain, D.C. Thinking differently about genetic counseling service delivery. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2015, 3, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzel, J.N.; Blazer, K.R.; MacDonald, D.J.; Culver, J.O.; Offit, K. Genetics, genomics, and cancer risk assessment: State of the Art and Future Directions in the Era of Personalized Medicine. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 327–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, K.; Kubendran, S.; Cohen, S.A. The past, present and future of service delivery in genetic counseling: Keeping up in the era of precision medicine. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2018, 178, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimshaw, J. A Knowledge Synthesis Chapter; Canadian Institutes of Health Research: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2010; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, W.D.; Knoppers, B.M.; Turnbull, C. Population genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: Founder mutations to genomes. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athens, B.A.; Caldwell, S.L.; Umstead, K.L.; Connors, P.D.; Brenna, E.; Biesecker, B.B. A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials to Assess Outcomes of Genetic Counseling. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 902–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meilleur, K.G.; Littleton-Kearney, M.T. Interventions to improve patient education regarding multifactorial genetic conditions: A systematic review. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2009, 149A, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, T.; Stowe, C.; Cole, A.; Lee, J.H.; Zhao, X.; Vadaparampil, S. Evaluation of phone-based genetic counselling in African American women using culturally tailored visual aids. Clin. Genet. 2010, 78, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutphen, R.; Davila, B.; Shappell, H.; Holtje, T.; Vadaparampil, S.; Friedman, S.; Toscano, M.; Armstrong, J. Real world experience with cancer genetic counseling via telephone. Fam. Cancer 2010, 9, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinney, A.Y.; Butler, K.M.; Schwartz, M.D.; Mandelblatt, J.S.; Boucher, K.M.; Pappas, L.M.; Gammon, A.; Kohlmann, W.; Edwards, S.L.; Stroup, A.M.; et al. Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: A cluster randomized trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.D.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Peshkin, B.N.; Mandelblatt, J.; Nusbaum, R.; Huang, A.T.; Chang, Y.; Graves, K.; Isaacs, C.; Wood, M.; et al. Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butrick, M.; Kelly, S.; Peshkin, B.N.; Luta, G.; Nusbaum, R.; Hooker, G.W.; Graves, K.; Feeley, L.; Isaacs, C.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; et al. Disparities in uptake of BRCA1/2 genetic testing in a randomized trial of telephone counseling. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peshkin, B.N.; Kelly, S.; Nusbaum, R.H.; Similuk, M.; DeMarco, T.A.; Hooker, G.W.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Forman, A.D.; Joines, J.R.; Davis, C.; et al. Patient Perceptions of Telephone vs. In-Person BRCA1/BRCA2 Genetic Counseling. J. Genet. Couns. 2016, 25, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinney, A.Y.; Steffen, L.E.; Brumbach, B.H.; Kohlmann, W.; Du, R.; Lee, J.H.; Gammon, A.; Butler, K.; Buys, S.S.; Stroup, A.M.; et al. Randomized Noninferiority Trial of Telephone Delivery of BRCA1/2 Genetic Counseling Compared With In-Person Counseling: 1-Year Follow-Up. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2914–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffen, L.E.; Du, R.; Gammon, A.; Mandelblatt, J.S.; Kohlmann, W.K.; Lee, J.H.; Buys, S.S.; Stroup, A.M.; Campo, R.A.; Flores, K.G.; et al. Genetic Testing in a Population-Based Sample of Breast and Ovarian Cancer Survivors from the REACH Randomized Trial: Cost Barriers and Moderators of Counseling Mode. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 1772–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Agincourt-Canning, L.; McGillivray, B.; Panabaker, K.; Scott, J.; Pearn, A.; Ridge, Y.; Portigal-Todd, C. Evaluation of genetic counseling for hereditary cancer by videoconference in British Columbia. BC Med. J. 2008, 50, 554–559. [Google Scholar]

- Zilliacus, E.M.; Meiser, B.; Lobb, E.A.; Kirk, J.; Warwick, L.; Tucker, K. Women’s experience of telehealth cancer genetic counseling. J. Genet. Couns. 2010, 19, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilliacus, E.M.; Meiser, B.; Lobb, E.A.; Kelly, P.J.; Barlow-Stewart, K.; Kirk, J.A.; Spigelman, A.D.; Warwick, L.J.; Tucker, K.M. Are videoconferenced consultations as effective as face-to-face consultations for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer genetic counseling? Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meropol, N.J.; Daly, M.B.; Vig, H.S.; Manion, F.J.; Manne, S.L.; Mazar, C.; Murphy, C.; Solarino, N.; Zubarev, V. Delivery of Internet-based cancer genetic counselling services to patients’ homes: A feasibility study. J. Telemed. Telecare 2011, 17, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, A.H.; Datta, S.K.; Skinner, C.S.; Hollowell, G.P.; Beresford, H.F.; Freeland, T.; Rogers, B.; Boling, J.; Marcom, P.K.; Adams, M.B. Randomized Trial of Telegenetics vs. In-Person Cancer Genetic Counseling: Cost, Patient Satisfaction and Attendance. J. Genet. Couns. 2015, 24, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, A.; Patrick-Miller, L.; Harris, D.; Stevens, E.; Egleston, B.; Smith, K.; Mueller, R.; Brandt, A.; Stopfer, J.; Rauch, S.; et al. Utilizing Remote Real-Time Videoconferencing to Expand Access to Cancer Genetic Services in Community Practices: A Multicenter Feasibility Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mette, L.A.; Saldívar, A.M.; Poullard, N.E.; Torres, I.C.; Seth, S.G.; Pollock, B.H.; Tomlinson, G.E. Reaching high-risk underserved individuals for cancer genetic counseling by video-teleconferencing. J. Commun. Support. Oncol. 2016, 14, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomons, N.M.; Lamb, A.E.; Lucas, F.L.; McDonald, E.F.; Miesfeldt, S. Examination of the Patient-Focused Impact of Cancer Telegenetics Among a Rural Population: Comparison with Traditional In-Person Services. Telemed. J. E Health 2018, 24, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangerich, B.; Stichler, J.F. Breast and ovarian cancer: A new model for educating women. Nurs. Womens Health 2008, 12, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridge, Y.; Panabaker, K.; McCullum, M.; Portigal-Todd, C.; Scott, J.; McGillivray, B. Evaluation of group genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J. Genet. Couns. 2009, 18, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothwell, E.; Kohlmann, W.; Jasperson, K.; Gammon, A.; Wong, B.; Kinney, A. Patient outcomes associated with group and individual genetic counseling formats. Fam. Cancer 2012, 11, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchanda, R.; Burnell, M.; Loggenberg, K.; Desai, R.; Wardle, J.; Sanderson, S.C.; Gessler, S.; Side, L.; Balogun, N.; Kumar, A.; et al. Cluster-randomised non-inferiority trial comparing DVD-assisted and traditional genetic counselling in systematic population testing for BRCA1/2 mutations. J. Med. Genet. 2016, 53, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benusiglio, P.R.; Di Maria, M.; Dorling, L.; Jouinot, A.; Poli, A.; Villebasse, S.; Le Mentec, M.; Claret, B.; Boinon, D.; Caron, O. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: Successful systematic implementation of a group approach to genetic counselling. Fam. Cancer 2017, 16, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesman, C.; Rose, E.; Grant, A.; Zimilover, A.; Klugman, S.; Schreiber-Agus, N. Experiences from a pilot program bringing BRCA1/2 genetic screening to theUS Ashkenazi Jewish population. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kentwell, M.; Dow, E.; Antill, Y.; Wrede, C.D.; McNally, O.; Higgs, E.; Hamilton, A.; Ananda, S.; Lindeman, G.J.; Scott, C.L. Mainstreaming cancer genetics: A model integrating germline BRCA testing into routine ovarian cancer clinics. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 145, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senter, L.; O’Malley, D.M.; Backes, F.J.; Copeland, L.J.; Fowler, J.M.; Salani, R.; Cohn, D.E. Genetic consultation embedded in a gynecologic oncology clinic improves compliance with guideline-based care. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 147, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednar, E.M.; Oakley, H.D.; Sun, C.C.; Burke, C.C.; Munsell, M.F.; Westin, S.N.; Lu, K.H. A universal genetic testing initiative for patients with high-grade, non-mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer and the implications for cancer treatment. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 146, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pederson, H.J.; Hussain, N.; Noss, R.; Yanda, C.; O’Rourke, C.; Eng, C.; Grobmyer, S.R. Impact of an embedded genetic counselor on breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 169, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Riddell, D.; Seal, S.; Talukdar, S.; Mahamdallie, S.; Ruark, E.; Cloke, V.; Slade, I.; Kemp, Z.; Gore, M.; et al. Implementing rapid, robust, cost-effective, patient-centred, routine genetic testing in ovarian cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Ahmad Bashah, N.S.; Wong, S.W.; Mariapun, S.; Hassan, T.; Padmanabhan, H.; Lim, J.; Lau, S.Y.; Rahman, N.; Thong, M.K.; et al. Mainstreaming Genetic Counselling for Genetic Testing of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Ovarian Cancer Patients in Malaysia (MaGiC Study). Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28 (Suppl. 10), mdx729.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, N.; Huang, G.; Scambia, G.; Chalas, E.; Pignata, S.; Fiorica, J.; Van Le, L.; Ghamande, S.; González-Santiago, S.; Bover, I.; et al. Evaluation of a Streamlined Oncologist-Led BRCA Mutation Testing and Counseling Model for Patients with Ovarian Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1300–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, B.; Lanceley, A.; Kristeleit, R.S.; Ledermann, J.A.; Lockley, M.; McCormack, M.; Mould, T.; Side, L. Mainstreamed genetic testing for women with ovarian cancer: First-year experience. J. Med. Genet. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brierley, K.L.; Campfield, D.; Ducaine, W.; Dohany, L.; Donenberg, T.; Shannon, K.; Schwartz, R.C.; Matloff, E.T. Errors in delivery of cancer genetics services: Implications for practice. Conn. Med. 2010, 74, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, K.A.; Poll, A.; Llacuachaqui, M.; Nanda, S.; Tulman, A.; Mian, N.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Patient satisfaction and cancer-related distress among unselected Jewish women undergoing genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2. Clin. Gen. 2010, 78, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, K.A.; Mian, N.; Enmore, M.; Poll, A.; Llacuachaqui, M.; Nanda, S.; Sun, P.; Hughes, K.S.; Narod, S.A. Long-term follow-up of Jewish women with a BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation who underwent population genetic screening. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 133, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, T.; Lee, J.H.; Besharat, A.; Thompson, Z.; Monteiro, A.N.; Phelan, C.; Lancaster, J.M.; Metcalfe, K.; Sellers, T.A.; Vadaparampil, S.; et al. Modes of delivery of genetic testing services and the uptake of cancer risk management strategies in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Clin. Genet. 2014, 85, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, J.; Toscano, M.; Kotchko, N.; Friedman, S.; Schwartz, M.D.; Virgo, K.S.; Lynch, K.; Andrews, J.E.; Aguado Loi, C.X.; Bauer, J.E.; et al. Utilization and Outcomes of BRCA Genetic Testing and Counseling in a National Commercially Insured Population: The ABOUT Study. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sie, A.S.; van Zelst-Stams, W.A.; Spruijt, L.; Mensenkamp, A.R.; Ligtenberg, M.J.; Brunner, H.G.; Prins, J.B.; Hoogerbrugge, N. More breast cancer patients prefer BRCA-mutation testing without prior face-to-face genetic counseling. Fam. Cancer 2014, 13, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sie, A.S.; Spruijt, L.; van Zelst-Stams, W.A.; Mensenkamp, A.R.; Ligtenberg, M.J.; Brunner, H.G.; Prins, J.B.; Hoogerbrugge, N. High Satisfaction and Low Distress in Breast Cancer Patients One Year after BRCA-Mutation Testing without Prior Face-to-Face Genetic Counseling. J. Genet. Couns. 2016, 25, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaskocinska, I.; Shipman, H.; Drummond, J.; Thompson, E.; Buchanan, V.; Newcombe, B.; Hodgkin, C.; Barter, E.; Ridley, P.; Ng, R.; et al. New paradigms for BRCA1/BRCA2 testing in women with ovarian cancer: Results of the Genetic Testing in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer (GTEOC) study. J. Med. Gen. 2016, 53, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipman, H.; Flynn, S.; MacDonald-Smith, C.F.; Brenton, J.; Crawford, R.; Tischkowitz, M.; Hulbert-Williams, N.J.; Group, G.S. Universal BRCA1/BRCA2 Testing for Ovarian Cancer Patients is Welcomed, but with Care: How Women and Staff Contextualize Experiences of Expanded Access. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiser, B.; Quinn, V.F.; Gleeson, M.; Kirk, J.; Tucker, K.M.; Rahman, B.; Saunders, C.; Watts, K.J.; Peate, M.; Geelhoed, E.; et al. When knowledge of a heritable gene mutation comes out of the blue: Treatment-focused genetic testing in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, V.F.; Meiser, B.; Kirk, J.; Tucker, K.M.; Watts, K.J.; Rahman, B.; Peate, M.; Saunders, C.; Geelhoed, E.; Gleeson, M.; et al. Streamlined genetic education is effective in preparing women newly diagnosed with breast cancer for decision making about treatment-focused genetic testing: A randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høberg-Vetti, H.; Bjorvatn, C.; Fiane, B.E.; Aas, T.; Woie, K.; Espelid, H.; Rusken, T.; Eikesdal, H.P.; Listøl, W.; Haavind, M.T.; et al. BRCA1/2 testing in newly diagnosed breast and ovarian cancer patients without prior genetic counselling: The DNA-BONus study. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augestad, M.T.; Hoberg-Vetti, H.; Bjorvatn, C.; Sekse, R.J. Identifying Needs: A Qualitative Study of women’s Experiences Regarding Rapid Genetic Testing for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer in the DNA BONus Study. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, S.; Tomer, A.; Ben-Chetrit, A.; Olsha, O.; Strano, S.; Beeri, R.; Koka, S.; Fridman, H.; Djemal, K.; Glick, I.; et al. Population screening for BRCA1/BRCA2 founder mutations in Ashkenazi Jews: Proactive recruitment compared with self-referral. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, S.; Lahad, A.; Tomer, A.; Cohen, C.; Levy-Lahad, E.; Raz, A. Population screening for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations: Lessons from qualitative analysis of the screening experience. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landsbergen, K.M.; Prins, J.B.; Brunner, H.G.; van Duijvendijk, P.; Nagengast, F.M.; van Krieken, J.H.; Ligtenberg, M.; Hoogerbrugge, N. Psychological distress in newly diagnosed colorectal cancer patients following microsatellite instability testing for Lynch syndrome on the pathologist’s initiative. Fam. Cancer 2012, 11, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heald, B.; Plesec, T.; Liu, X.; Pai, R.; Patil, D.; Moline, J.; Sharp, R.R.; Burke, C.A.; Kalady, M.F.; Church, J.; et al. Implementation of universal microsatellite instability and immunohistochemistry screening for diagnosing lynch syndrome in a large academic medical center. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1336–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez, E.; Geng, Z.; Pass, S.; Summerour, P.; Robinson, L.; Sarode, V.; Gupta, S. Implementation of routine screening for Lynch syndrome in university and safety-net health system settings: Successes and challenges. Genet. Med. 2013, 15, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moline, J.; Mahdi, H.; Yang, B.; Biscotti, C.; Roma, A.A.; Heald, B.; Rose, P.G.; Michener, C.; Eng, C. Implementation of tumor testing for lynch syndrome in endometrial cancers at a large academic medical center. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 130, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, R.L.; Hicks, S.; Hawkins, N.J. Population-based molecular screening for Lynch syndrome: Implications for personalized medicine. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2554–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batte, B.A.; Bruegl, A.S.; Daniels, M.S.; Ring, K.L.; Dempsey, K.M.; Djordjevic, B.; Luthra, R.; Fellman, B.M.; Lu, K.H.; Broaddus, R.R. Consequences of universal MSI/IHC in screening ENDOMETRIAL cancer patients for Lynch syndrome. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 134, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.J.; Herda, M.M.; Handorf, E.A.; Rybak, C.C.; Keleher, C.A.; Siemon, M.; Daly, M.B. Direct-to-patient disclosure of results of mismatch repair screening for Lynch syndrome via electronic personal health record: A feasibility study. Genet. Med. 2014, 16, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolova, A.I.; Babb, S.A.; Zantow, E.; Hagemann, A.R.; Powell, M.A.; Thaker, P.H.; Gao, F.; Mutch, D.G. Impact of an immunohistochemistry-based universal screening protocol for Lynch syndrome in endometrial cancer on genetic counseling and testing. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 137, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidambi, T.D.; Blanco, A.; Myers, M.; Conrad, P.; Loranger, K.; Terdiman, J.P. Selective Versus Universal Screening for Lynch Syndrome: A Six-Year Clinical Experience. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 2463–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.E.; Zepp, J.M.; Gilmore, M.J.; Davis, J.V.; Esterberg, E.J.; Muessig, K.R.; Peterson, S.K.; Syngal, S.; Acheson, L.S.; Wiesner, G.L.; et al. Universal tumor screening for Lynch syndrome: Assessment of the perspectives of patients with colorectal cancer regarding benefits and barriers. Cancer 2015, 121, 3281–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goverde, A.; Spaander, M.C.; van Doorn, H.C.; Dubbink, H.J.; van den Ouweland, A.M.; Tops, C.M.; Kooi, S.G.; de Waard, J.; Hoedemaeker, R.F.; Bruno, M.J.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of routine screening for Lynch syndrome in endometrial cancer patients up to 70 years of age. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 143, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, B.; Hemmings, C.T.; Clark, I.; Yip, D.; Fadia, M.; Taupin, D.R. Universal molecular screening does not effectively detect Lynch syndrome in clinical practice. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2017, 10, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holter, S.P.A.; Brown, C.; Schaeffer, D.; Wang, H.; Deschenes, J.; Foulkes, W.; Karanicolas, P.; Hsieh, E.; Hart, T.; Streutker, C.; et al. Screening for Lynch syndrome through the Canadian colorectal cancer consortium. Fam. Cancer 2017, 16, S32–S33. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J.E.; Arnold, K.A.; Cook, J.E.; Zepp, J.; Gilmore, M.J.; Rope, A.F.; Davis, J.V.; Bergen, K.M.; Esterberg, E.; Muessig, K.R.; et al. Universal screening for Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer: Patient perspectives on screening and sharing results with at-risk relatives. Fam. Cancer 2017, 16, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupfer, S.M.C.; Barge, W.; Chang, J.; Peterson, M.; Stoll, J.; Berera, S.; Wideroff, G.; Sussman, D.; Melson, J. Is universal tumor testing for lynch syndrome truly universal? Fam. Cancer 2017, 16, S80–S81. [Google Scholar]

- Livi, A.; Turchetti, D.; Miccoli, S.; Godino, L.; Ferrari, S.; Zuntini, R.; Procaccini, M.; Della Gatta, A.N.; De Leo, A.; Ceccarelli, C.; et al. Routine mismatch repair immunohistochemistry analysis as a valuable method to improve lynch syndrome’s diagnosis among women with endometrial cancer. Fam. Cancer 2017, 16, S100–S101. [Google Scholar]

- Najdawi, F.; Crook, A.; Maidens, J.; McEvoy, C.; Fellowes, A.; Pickett, J.; Ho, M.; Nevell, D.; McIlroy, K.; Sheen, A.; et al. Lessons learnt from implementation of a Lynch syndrome screening program for patients with gynaecological malignancy. Pathology 2017, 49, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kane, G.M.; Ryan, É.; McVeigh, T.P.; Creavin, B.; Hyland, J.M.; O’Donoghue, D.P.; Keegan, D.; Geraghty, R.; Flannery, D.; Nolan, C.; et al. Screening for mismatch repair deficiency in colorectal cancer: Data from three academic medical centers. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.R.-B.M.; Mork, M.; Bannon, S.; Cuddy, A.; Vilar, E.; Pande, M.; Lynch, P.; You, YN. Decision for non-completion of follow up among patients with abnormal screening test for hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome. Fam. Cancer 2017, 16, 1–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.C.; Yang, E.J.; Muto, M.G.; Feltmate, C.M.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Horowitz, N.S.; Syngal, S.; Yurgelun, M.B.; Chittenden, A.; Hornick, J.L.; et al. Universal Screening for Mismatch-Repair Deficiency in Endometrial Cancers to Identify Patients with Lynch Syndrome and Lynch-like Syndrome. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2017, 36, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, B.B.J.; Kim, A.; Batts, K.; Burgart, L.; Baldinger, S.; Jensen, C. Treatment implications of universal mismatch repair gene screening in colorectal cancer patients. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2018, 61, e144. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, M.J.; Petros, F.G.; Rao, P.; Mork, M.E.; Xiao, L.; Broaddus, R.R.; Matin, S.F. Universal Point of Care Testing for Lynch Syndrome in Patients with Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. J. Urol. 2018, 199, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miesfeldt, S.; Feero, W.G.; Lucas, F.L.; Rasmussen, K. Association of patient navigation with care coordination in a Lynch syndrome screening program. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018, 8, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, S.W.; Park, E.R.; Najita, J.; Martins, Y.; Traeger, L.; Bair, E.; Gagne, J.; Garber, J.; Jänne, P.A.; Lindeman, N.; et al. Oncologists’ and cancer patients’ views on whole-exome sequencing and incidental findings: Results from the CanSeq study. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, A.P.M.; Pocock, R.H.; Switchenko, J.M.; Dixon, M.D.; Shaib, W.L.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Pentz, R.D. Discussing molecular testing in oncology care: Comparing patient and physician information preferences. Cancer 2017, 123, 1610–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, M.; Newson, A.J.; Meiser, B.; Juraskova, I.; Goldstein, D.; Tucker, K.; Ballinger, M.L.; Hess, D.; Schlub, T.E.; Biesecker, B.; et al. The PiGeOn project: Protocol of a longitudinal study examining psychosocial and ethical issues and outcomes in germline genomic sequencing for cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumish, H.S.; Steinfeld, H.; Koval, C.; Russo, D.; Levinson, E.; Wynn, J.; Duong, J.; Chung, W.K. Impact of Panel Gene Testing for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer on Patients. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 1116–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, S.C.; Rini, C.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Valdimarsdottir, H.; Cohen, L.H.; Schwartz, M.D. Distress among women receiving uninformative BRCA1/2 results: 12-month outcomes. Psycho-Oncology 2009, 18, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Country | Population | Selected Outcomes: GC Referral Rates [A], GC Attendance [B], GT Uptake [C], Wait Time [D], GC Time [E], Satisfaction [F], Knowledge [G], Psychosocial [H], Health Behaviors [I], Patient Preferences [J] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pal et al. (2010) [33] | USA | African American women with BC ≤ 50 receiving telephone GC with tailored counseling aid (n = 37) |

|

| Sutphen et al. (2010) [34] | USA | Health insurance company employees receiving telephone GC after screening positive for HBOC risk (n = 39) |

|

| Kinney et al. (2014) [35] * | USA | Randomized trial of rural and urban women aged 25–74 years with a personal/family history suggestive of HBOC who had telephone (n = 437) or traditional (n = 464) GC |

|

| Schwartz et al. (2014) [36] ** | USA | Randomized trial of women aged 21–85 years with ≥10% risk of a BRCA mutation who had telephone (n = 298) or traditional (n = 302) GC |

|

| Butrick et al. (2015) [37] ** | USA | Randomized trial of women aged 21–85 years with ≥10% risk of a BRCA mutation who had telephone (n = 298) or traditional (n = 302) GC |

|

| Peshkin et al. (2015) [38] ** | USA | Randomized trial of women aged 21–85 years with ≥10% risk of a BRCA mutation who had telephone (n = 272) or traditional (n = 282) GC |

|

| Kinney et al. (2016) [39] * | USA | Randomized trial of rural and urban women aged 25–74 years with a personal or family history suggestive of HBOC who had telephone (n = 409) or traditional (n = 383) GC |

|

| Steffen et al. (2017) [40] * | USA | Randomized trial of rural and urban women aged 25–74 years with known mutation status who had telephone (n = 402) or traditional (n = 379) GC for HBOC |

|

| Study | Country | Population | Selected Outcomes: GC Referral Rates [A], GC Attendance [B], GT Uptake [C], Wait Time [D], GC Time [E], Satisfaction [F], Knowledge [G], Psychosocial [H], Health Behaviors [I], Patient Preferences [J] |

|---|---|---|---|

| d’Agincourt-Canning et al. (2008) [41] | CAN | Patients (n = 43) and family members (n = 5) having telegenetic GC for hereditary cancer |

|

| Zilliacus et al. (2010) [42] * | AUS | Qualitative study of women who received GC for HBOC, where a genetic physician provided telegenic GC with a local genetic counselor present in-person (n = 12) |

|

| Zilliacus et al. (2011) [43] * | AUS | Patients receiving traditional (n = 89) or telegenetic (n = 106) GC for HBOC, where a genetic physician provided telegenic GC with a local genetic counselor present in-person |

|

| Meropol et al. (2011) [44] | USA | Patients and families receiving telegenetic GC for hereditary CRC or HBOC (n = 31) |

|

| Buchanan et al. (2015) [45] | USA | Randomized trial of individuals receiving telegenetic (n = 59) or traditional (n = 71) GC for hereditary cancer risk. |

|

| Bradbury et al. (2016) [46] | USA | Patients >20 years eligible for GT (HBOC or CRC) receiving telegenic GC (n = 61) |

|

| Mette et al. (2016) [47] | USA | Patients receiving telegenetic (n = 56) or traditional (n = 63) GC for hereditary cancer risk |

|

| Solomons et al. (2018) [48] | USA | New patients seen by genetics for personal/family history of cancer receiving telegenetic (n = 90) or traditional (n = 68) GC |

|

| Study | Country | Population | Selected Outcomes: GC Referral Rates [A], GC Attendance [B], GT Uptake [C], Wait Time [D], GC Time [E], Satisfaction [F], Knowledge [G], Psychosocial [H], Health Behaviors [I], Patient Preferences [J] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mangerich et al. (2008) [49] | USA | Individuals interested in BRCA GT (n = 15; 6 with BC) attending a group education class |

|

| Ridge et al. (2009) [50] | CAN | Women offered appointments for GC, including: group GC (n = 42), traditional GC (n = 37), OC patients receiving group GC (n = 10) |

|

| Rothwell et al. (2012) [51] | USA | Women with or at high risk of BC/OC receiving group (n = 17) or traditional (n = 32) GC |

|

| Manchanda et al. (2016) [52] | UK | Randomized trial of Ashkenazi Jewish men/women without previous BRCA testing receiving group DVD (n = 409) or traditional (n = 527) GC |

|

| Benusiglio et al. (2017) [53] | FRA | BC and OC patients eligible for BRCA GT receiving group (n = 210) or traditional (n = 47) GC |

|

| Wiesman et al. (2017) [54] | USA | Ashkenazi Jewish men/women at low risk of a BRCA mutation receiving group GC (n = 88) |

|

| Study | Country | Population | Selected Outcomes: GC Referral Rates [A], GC Attendance [B], GT Uptake [C], Wait Time [D], GC Time [E], Satisfaction [F], Knowledge [G], Psychosocial [H], Health Behaviors [I], Patient Preferences [J] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kentwell et al. (2017) [55] | AUS | Non-mucinous OC patients diagnosed <70 years before (n = 134) and after (n = 99) the implementation of embedded GC |

|

| Senter et al. (2017) [56] | USA | Newly diagnosed OC patients before (n = 401) and after (n = 336) the implementation of embedded GC |

|

| Bednar et al. (2017) [57] * | USA | OC patients (n = 1636) seen after implementation of embedded GC, mainstreaming GT, and GC-assisted referral processes |

|

| Pederson et al. (2018) [58] | USA | Newly diagnosed BC patients before (n = 471) and after (n = 440) implementation of embedded GC |

|

| Study | Country | Population | Selected Outcomes: GC Referral Rates [A], GC Attendance [B], GT Uptake [C], Wait Time [D], GC Time [E], Satisfaction [F], Knowledge [G], Psychosocial [H], Health Behaviors [I], Patient Preferences [J] |

|---|---|---|---|

| George et al. (2016) [59] | UK | OC patients (n = 207) receiving BRCA GT via their oncology team |

|

| Bednar et al. (2017) [57] | USA | OC patients (n = 197) seen at regional oncology clinic |

|

| Yoon et al. (2017) [60] | MAL | Conference abstract: OC patients (n = 208) receiving BRCA GT via their oncology team |

|

| Colombo et al. (2018) [61] | USAITAESP | OC patients (n = 634) receiving BRCA GT via their oncology team |

|

| Rahman et al. (2018) [62] | UK | OC patients (n = 122) receiving BRCA GT via oncology team |

|

| Study | Country | Population | Selected Outcomes: GC Referral Rates [A], GC Attendance [B], GT Uptake [C], Wait Time [D], GC Time [E], Satisfaction [F], Knowledge [G], Psychosocial [H], Health Behaviors [I], Patient Preferences [J] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brierley et al. (2010) [63] | USA | Series of cases without pre-test GC (n = 21) |

|

| Metcalfe et al. (2010) [64] * | CAN | Ashkenazi Jewish women aged 25–80 years (n = 1516) pursuing BRCA GT using the direct GT model with written information |

|

| Metcalfe et al. (2012) [65] * | CAN | Ashkenazi Jewish women aged 25–80 years identified to have a BRCA mutation via direct GT with written information (n = 19) |

|

| Pal et al. (2014) [66] | USA | Women in the Inherited Cancer Registry database with BRCA mutation (n = 438) |

|

| Armstrong et al. (2015) [67] | USA | Women who had BRCA GT with (n = 1334) or without (n = 2247) pre-test GC |

|

| Sie et al. (2014) [68] # | NED | Women with BC referred for BRCA GT electing to have direct GT (n = 95) or pre-test GC (n = 66) |

|

| Sie et al. (2016) [69] # | NED | Women with BC referred for BRCA GT electing to have direct GT (n = 59, incl 5 BRCA+) or pre-test GC (n = 49, incl 1 BRCA+) |

|

| Plaskocinska et al. (2016) [70] ## | UK | Women with a recent (<12 months) diagnosis of OC (n = 173) who had direct BRCA GT |

|

| Shipman et al. (2017) [71] ## | UK | Qualitative Study of women diagnosed with OC in last 12 months with positive (n = 4), negative (n = 5) and inconclusive (n = 3) GT results from direct BRCA GT |

|

| Meiser et al. (2016) [72] ^ | AUS | Qualitative Study of women aged 18–49 years with BC who received BRCA GT with pre-test GC or direct GT with written information who were BRCA+/fhx+ (n = 5) BRCA+/fhx− (n = 5), BRCA−/fhx+ (n = 5), or BRCA−/fhx− (n = 5) |

|

| Quinn et al. (2017) [73] ^ | AUS | Women aged 18–49 years with BC who received treatment focused BRCA GT with pre-test GC (n = 70) or direct GT with written information (n = 65) |

|

| Høberg-Vetti et al. (2016) [74] ^^ | NOR | Women offered direct BRCA GT with written information after a new diagnosis of BC (n = 893) or OC (n = 122) |

|

| Augestad et al. (2017) [75] ^^ | NOR | Qualitative study of women newly diagnosed with BC (n = 13) or OC (n = 4) who received direct BRCA GT with written information |

|

| Lieberman et al. (2017a) [76] ** | ISR | Ashkenazi Jewish individuals aged ≥25 years who were self- (n = 744) or recruiter (n = 1027) enrolled for direct BRCA GT with written information |

|

| Lieberman et al. (2017b) [77] ** | ISR | Qualitative Study of Ashkenazi Jewish individuals ≥25 who were BRCA+ (n = 26) or BRCA− (n = 10) after direct GT with written information |

|

| Study | Country | Population | Selected Outcomes: GC Referral Rates [A], GC Attendance [B], GT Uptake [C], Wait Time [D], GC Time [E], Satisfaction [F], Knowledge [G], Psychosocial [H], Health Behaviors [I], Patient Preferences [J] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies of tumor screening for Lynch Syndrome: | |||

| Landsbergen et al. (2012) [78] | NED | Recently diagnosed CRC < 50 OR second CRC < 70 years old (n = 400) who had tumor screening. |

|

| Heald et al. (2013) [79] | USA | CRC where universal screening results went only to the surgeon (n = 237), to the surgeon and genetics (n = 87), and to the surgeon and genetics with a genetic counselor contacting the patient (n = 784) |

|

| Marquez et al. (2013) [80] | USA | Universal tumor screening of CRC ≤ 70 years old (n = 129) |

|

| Moline et al. (2013) [81] | USA | Universal tumor screening of EC patients (n = 245) |

|

| Ward et al. (2013) [82] | AUS | CRC patients with mismatch repair deficient tumors (n = 245) |

|

| Batte et al. (2014) [83] | USA | Universal screening of unselected EC (retrospective = 408; prospective = 206) |

|

| Hall et al. (2014) [84] | USA | Consecutive CRC and EC patients who had reliable internet access (n = 66) whose tumor screening results were disclosed directly via their electronic medical record |

|

| Frolova et al. (2015) [85] | USA | EC before (n = 395) and after (n = 242) the implementation of universal tumor screening |

|

| Kidambi et al. (2015) [86] | USA | CRC in selected (<50 or <60 with features of Lynch syndrome; n = 107) and universal screening groups (n = 285) |

|

| Hunter et al. (2015) [87] | USA | CRC patients undergoing universal tumor screening (n = 145) |

|

| Goverde et al. (2016) [88] | NED | Consecutive series of EC patients ≤70 years (n = 179) having tumor screening |

|

| Brennan et al. (2017) [89] | AUS | Consecutive series of CRC patients (n = 1612) having tumor screening |

|

| Holter et al. (2017) [90] | CAN | Conference abstract: CRC cancer patients <60 years (n = 502) undergoing tumor screening |

|

| Hunter et al. (2017) [91] | USA | Newly diagnosed CRC patients (n = 189) undergoing tumor screening |

|

| Kupfer et al. (2017) [92] | USA | Conference abstract: CRC in White (n = 266) African American (n = 174), and Hispanic (n = 125) patients having tumor screening |

|

| Livi et al. (2017) [93] | ITA | Conference abstract: Consecutive EC patients (n = 166) having tumor screening |

|

| Najdawi et al. (2017) [94] | AUS | Patients with EC (any histology) and endometroid or clear cell gynecological cancer (n = 124) having tumor screening |

|

| O’Kane et al. (2017) [95] | IRL | CRC patients having tumor screening at one of three centers (n = 3906) |

|

| Patel et al. (2017) [96] | USA | Conference abstract: Consecutive CRC patients (n = 1597) having tumor screening |

|

| Watkins et al. (2017) [97] | USA | EC patients (n = 242) having tumor screening |

|

| Martin et al. (2018) [98] | USA | Newly diagnosed CRC patients (n = 78) having tumor screening |

|

| Metcalfe et al. (2018) [99] | USA | Consecutive upper tract urothelial cancer patients (n = 115) having tumor screening |

|

| Miesfeldt et al. (2018) [100] | USA | CRC (n = 175) or EC (n = 276) patients where results were sent to a surgeon, patient navigator, or both |

|

| Studies of tumor genetic testing | |||

| Gray et al. (2016) [101] | USA | Patients with stage IV lung or CRC (n = 167) enrolled in a tumor testing study |

|

| Pinheiro et al. (2017) [102] | USA | Cancer patients being offered or receiving tumor results (n = 66) |

|

| Best et al. (2018) [103] | AUS | Patients with advanced solid tumors participating in a molecular tumor screening study (n > 369) |

|

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCuaig, J.M.; Armel, S.R.; Care, M.; Volenik, A.; Kim, R.H.; Metcalfe, K.A. Next-Generation Service Delivery: A Scoping Review of Patient Outcomes Associated with Alternative Models of Genetic Counseling and Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers10110435

McCuaig JM, Armel SR, Care M, Volenik A, Kim RH, Metcalfe KA. Next-Generation Service Delivery: A Scoping Review of Patient Outcomes Associated with Alternative Models of Genetic Counseling and Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer. Cancers. 2018; 10(11):435. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers10110435

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCuaig, Jeanna M., Susan Randall Armel, Melanie Care, Alexandra Volenik, Raymond H. Kim, and Kelly A. Metcalfe. 2018. "Next-Generation Service Delivery: A Scoping Review of Patient Outcomes Associated with Alternative Models of Genetic Counseling and Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer" Cancers 10, no. 11: 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers10110435

APA StyleMcCuaig, J. M., Armel, S. R., Care, M., Volenik, A., Kim, R. H., & Metcalfe, K. A. (2018). Next-Generation Service Delivery: A Scoping Review of Patient Outcomes Associated with Alternative Models of Genetic Counseling and Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer. Cancers, 10(11), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers10110435