A CMOS-Compatible Silicon Nanowire Array Natural Light Photodetector with On-Chip Temperature Compensation Using a PSO-BP Neural Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

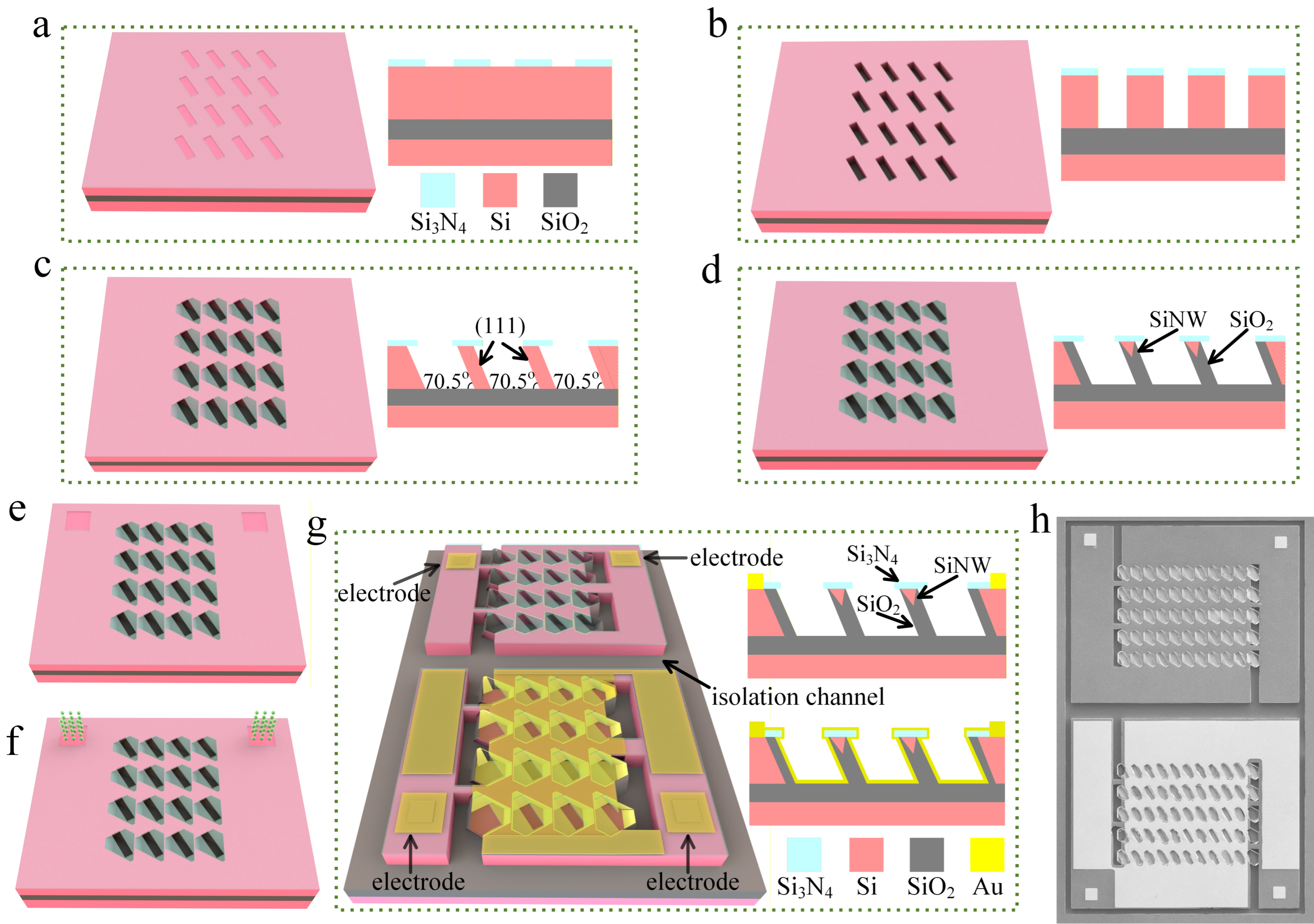

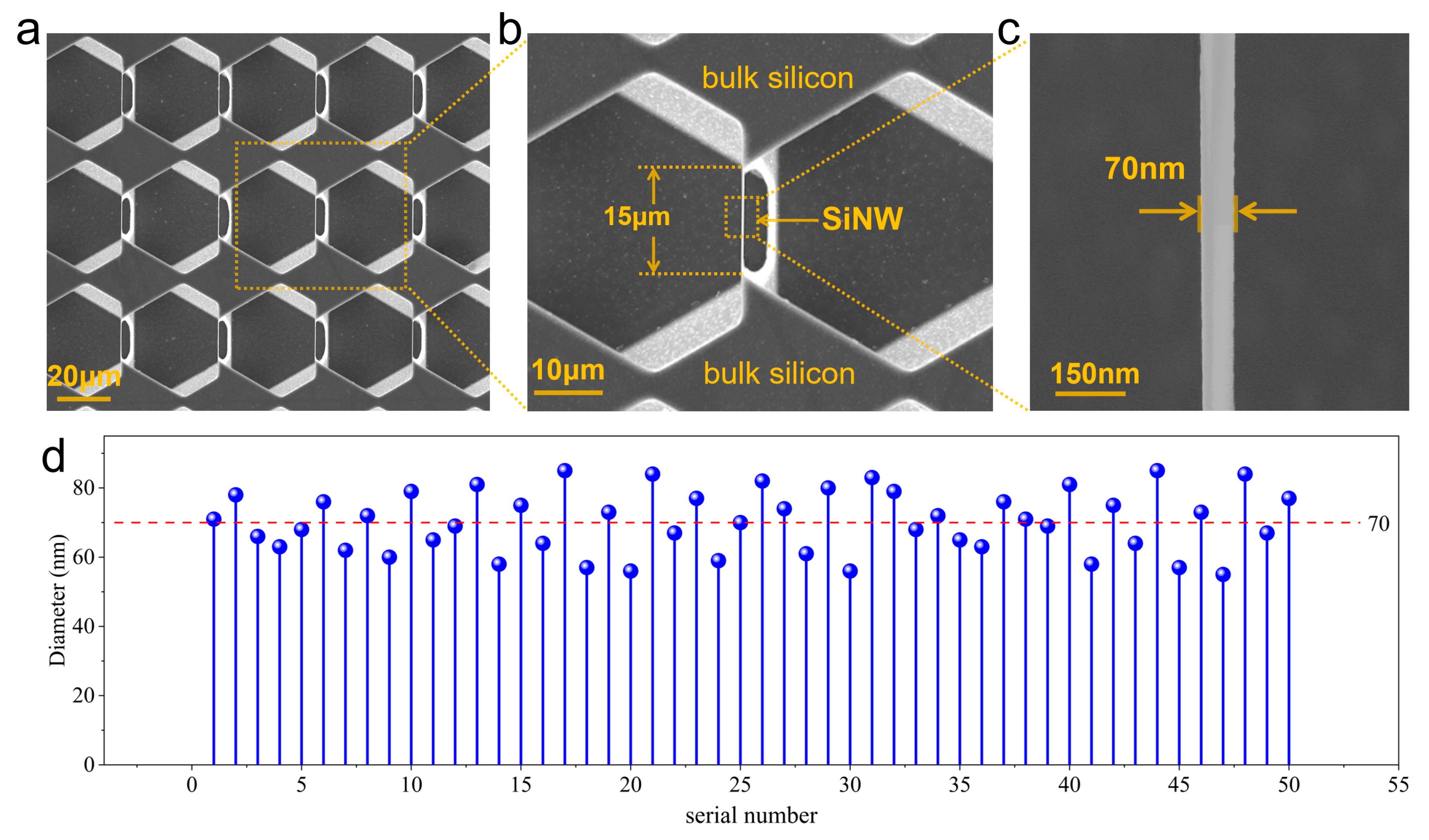

2. Materials and Methods

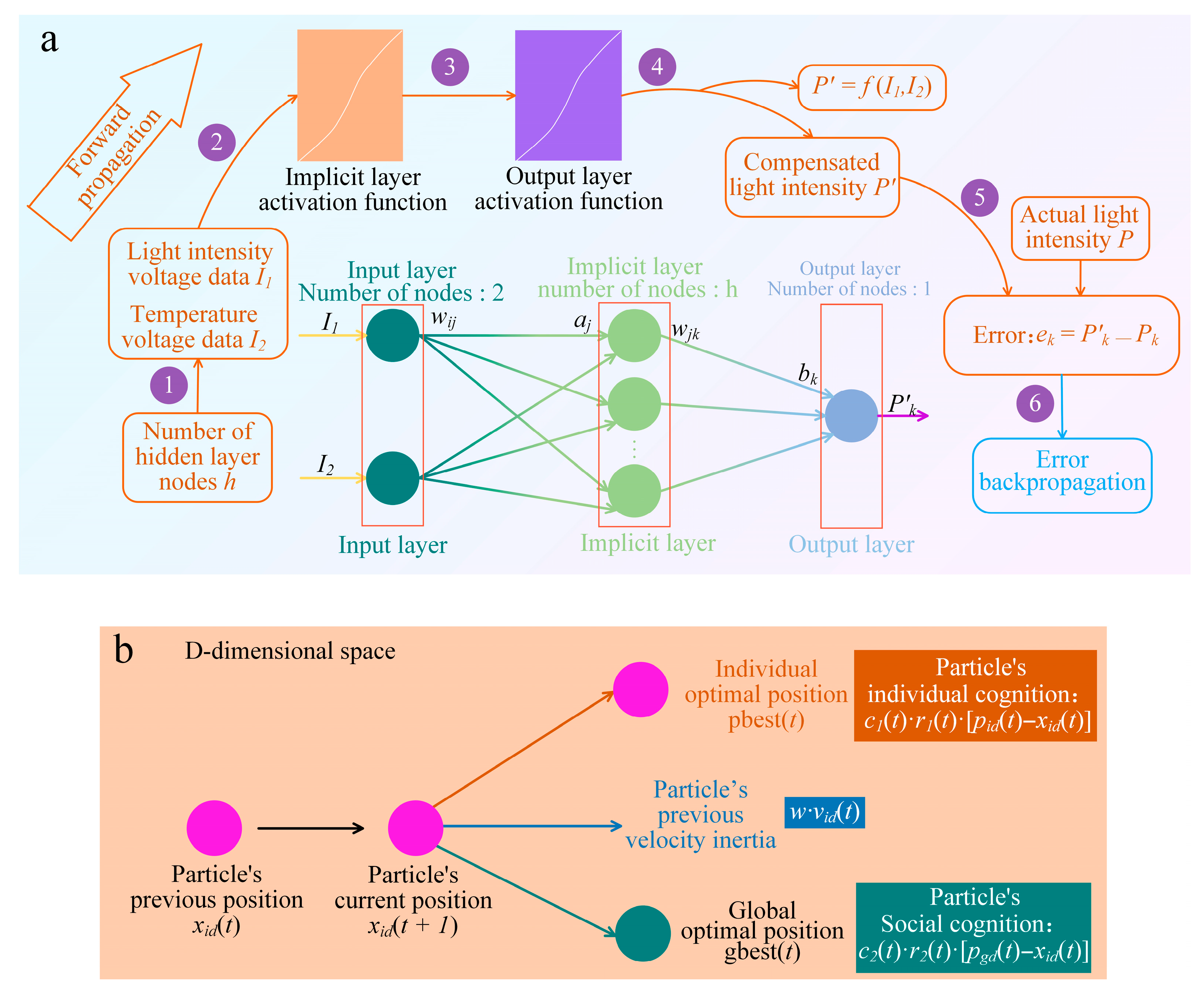

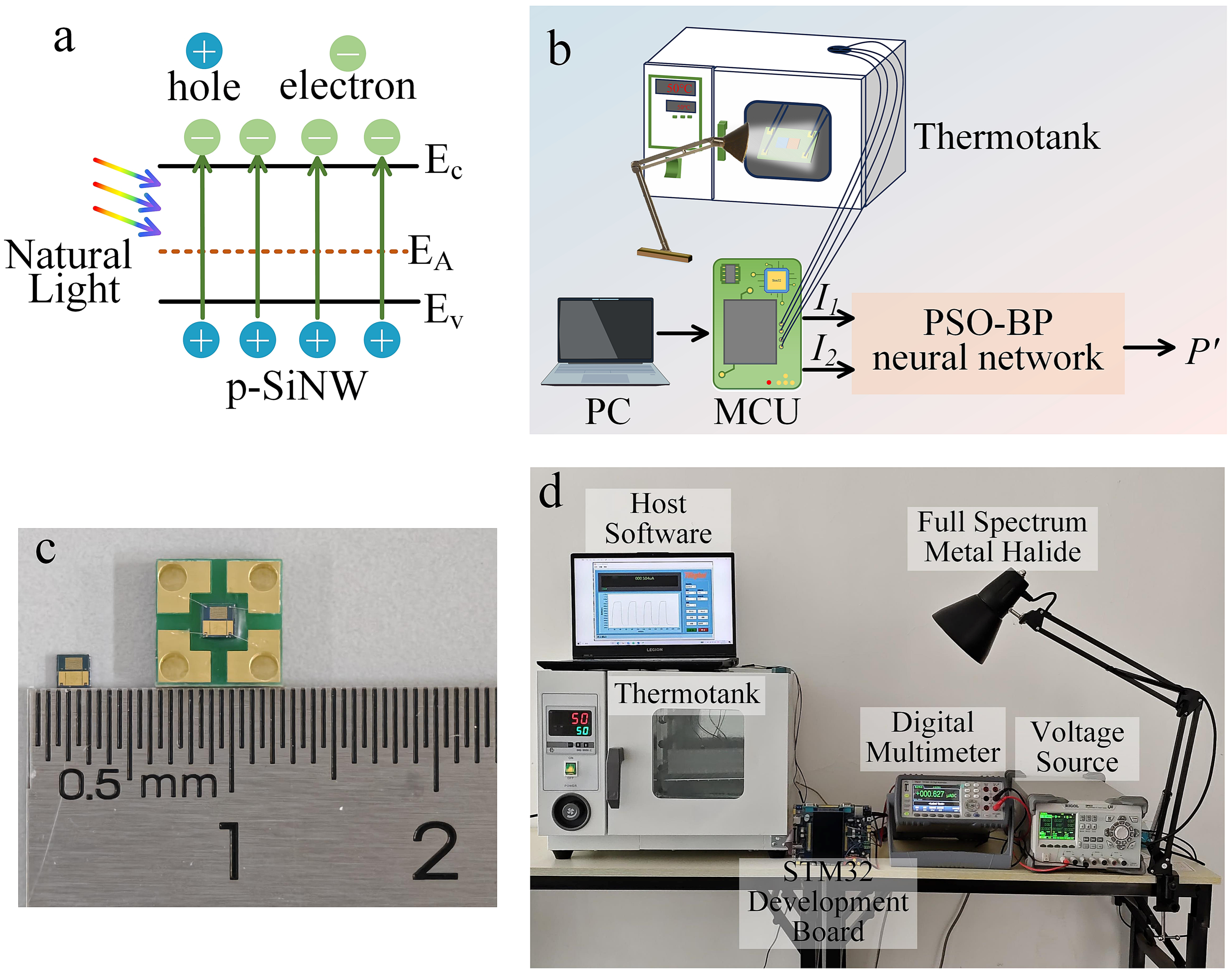

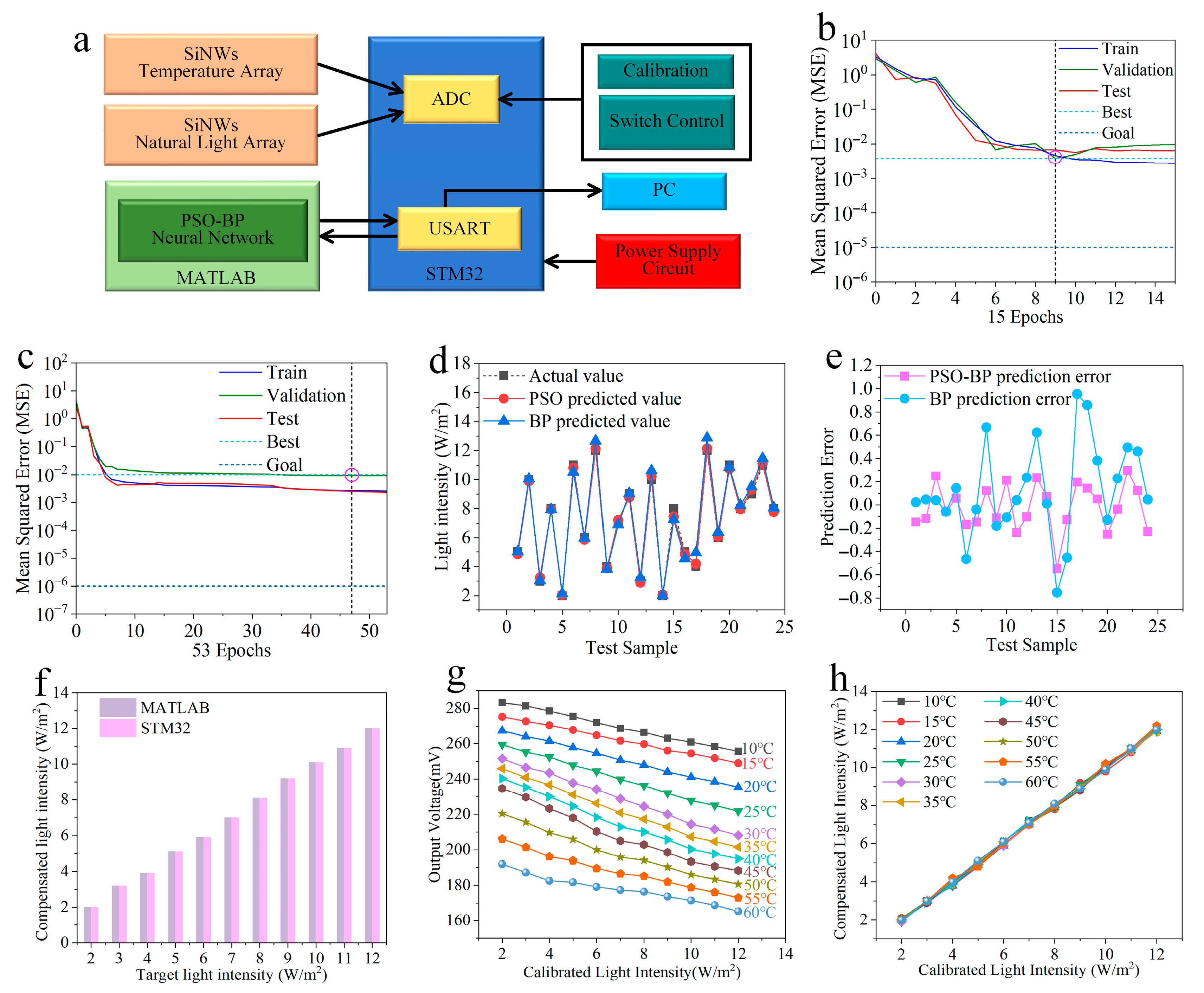

3. Temperature Compensation Principle

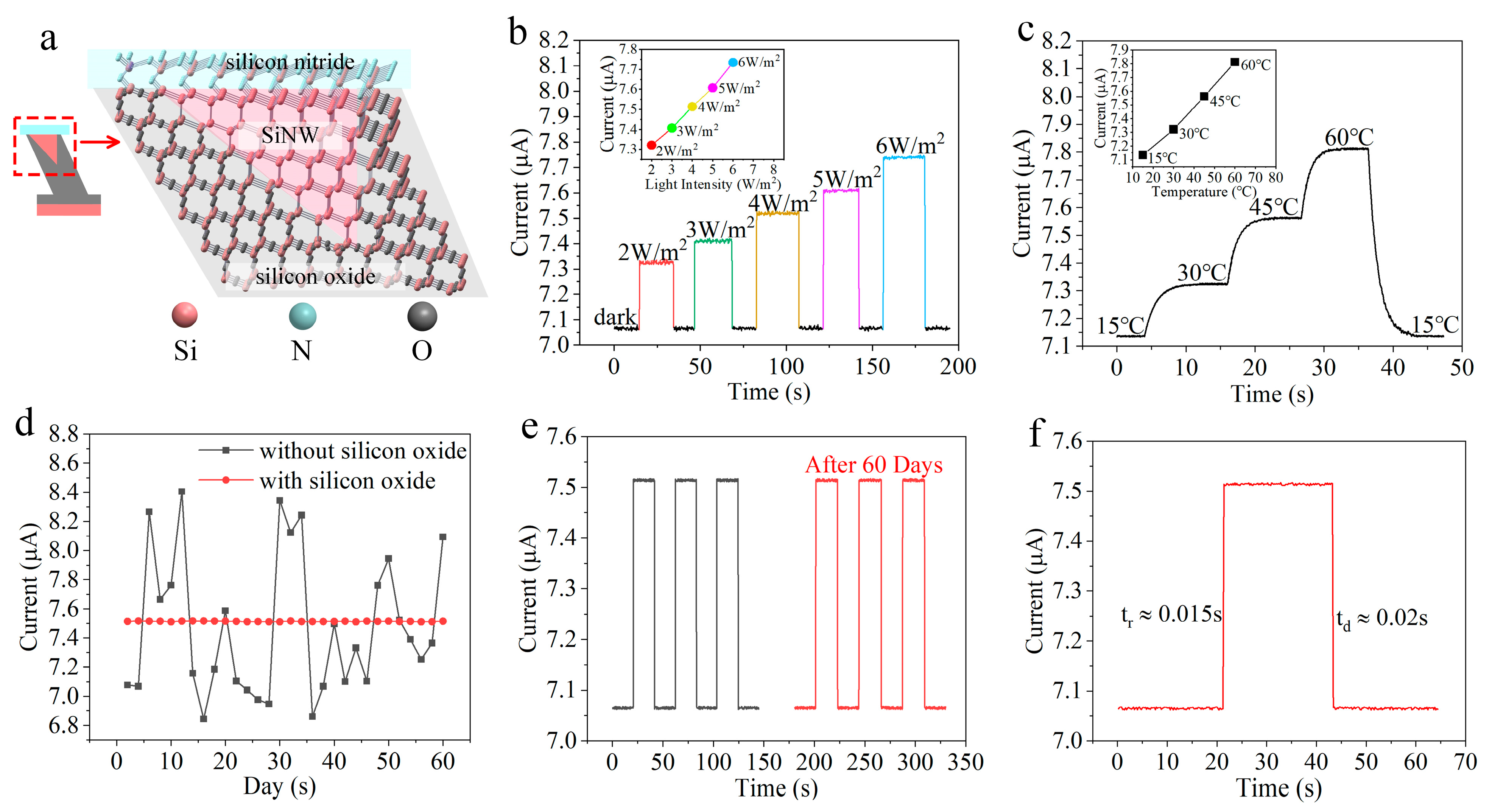

4. Results and Discussion

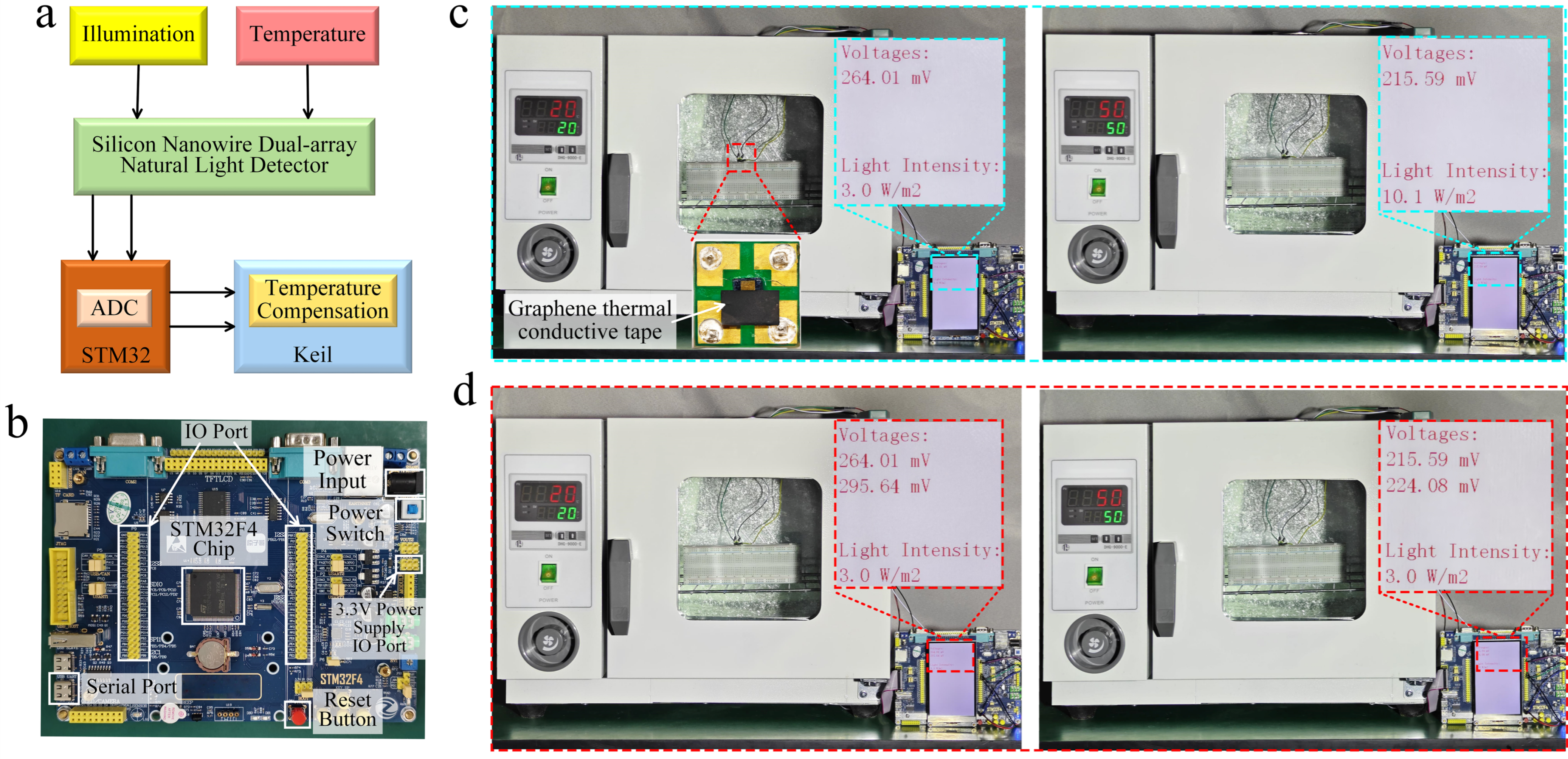

4.1. Construction of the Testing System

4.2. Response Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Vita, C.; Toso, F.; Pruiti, N.G.; Klitis, C.; Ferrari, G.; Sorel, M.; Melloni, A.; Morichetti, F. Amorphous-silicon visible-light detector integrated on silicon nitride waveguides. Opt. Lett. 2022, 47, 2598–2601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Tao, L.; Zhu, H.; Lin, W.; Chen, J.; Fang, Y. Silicon-based narrowband photodetectors with blade-coated perovskite light extinction layer for high performance visible-blind NIR detection. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jia, Z.; Lv, X.; Huang, X. Biological detection based on the transmitted light image from a porous silicon microcavity. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 12184–12189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jia, Z.; Lü, X.; Huang, X.; Wang, J. Digital image biological detection technology based on the porous silicon periodic crystals film. Optoelectron. Lett. 2021, 17, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yong, Z.; Luo, X.; Azadeh, S.S.; Mikkelsen, J.C.; Sharma, A.; Chen, H.; Mak, J.C.C.; Lo, P.G.-Q.; Sacher, W.D.; et al. Monolithically integrated, broadband, high-efficiency silicon nitride-on-silicon waveguide photodetectors in a visible-light integrated photonics platform. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Xu, X.; Yang, W.; Chen, J.; Fang, X. Materials and designs for wearable photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1808138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.L.; Tsai, D.S.; Tang, L.; Chen, L.J.; Lau, S.P.; He, J.H. Omnidirectional harvesting of weak light using a graphene quantum dot-modified organic/silicon hybrid device. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4564–4570. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Zhao, C.Z. Recent progress in silicon photonics: A review. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 2012, 428690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, J.; Yu, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Shi, Y.; Dai, D. Silicon/2D-material photodetectors: From near-infrared to mid-infrared. Light Sci. Appl. 2021, 10, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, P.; Brandt, J. Temperature coefficient of resistance for p-and n-type silicon. Solid-State Electron. 1978, 21, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; You, S.; Soci, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Lo, Y.-H. Silicon nanowire detectors showing phototransistive gain. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 121110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.F.; Fu, C.; Li, Y.H.; Yu, B.; Shi, F.; Gao, Y.M.; Long, S.J.; Liang, F.X.; Luo, L.B. Study of Ultranarrowband Silicon Nanowire Array Photodetector with Peak Spectral Responsivity at 1120 nm. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 32848–32857. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalache, I.; Radoi, A.; Pascu, R.; Romanitan, C.; Vasile, E.; Kusko, M. Engineering graphene quantum dots for enhanced ultraviolet and visible light p-Si nanowire-based photodetector. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 29234–29247. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.C.; Jie, J.S.; Shao, Z.B.; Huang, S.Y.; He, L.; Zhang, X.H. One-step growth of large-area silicon nanowire fabrics for high-performance multifunctional wearable sensors. Nano Res. 2019, 12, 2723–2728. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Muñoz, D.; García-Gil, R.; Cardoso, S.; Freitas, P. Characterization of Magnetoresistive Shunts and Its Sensitivity Temperature Compensation. Sensors 2024, 24, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, F.; Li, J.; Ji, Y.; Song, H.; Wang, B. Research on TMR current transducer with temperature compensation based on reference magnetic field. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 121828–121834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhou, K.; Jin, Q.; Lu, B.; Jin, Z.; Chen, J. A High-Precision Temperature Compensation Method for TMR Weak Current Sensors Based on FPGA. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Včelák, J.; Ripka, P.; Platil, A.; Kubík, J.; Kašpar, P. Errors of AMR compass and methods of their compensation. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2006, 129, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.; Hua, C.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Yu, W.; Yu, H. Temperature Compensation Method Based on Bilinear Interpolation for Downhole High-Temperature Pressure Sensors. Sensors 2024, 24, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, H.J. Research on Temperature Compensation Method of Pressure Sensor Based on BP Neural Network. Chin. J. Sens. Actuators 2020, 33, 688–692, 732. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Li, G.; Wu, Y.; Long, X. Application of Least Squares-Support Vector Machine in system-level temperature compensation of ring laser gyroscope. Measurement 2011, 44, 1898–1903. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Hu, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zou, C.; Peng, W.; Alam Sm, J. Study on temperature and synthetic compensation of piezo-resistive differential pressure sensors by coupled simulated annealing and simplex optimized kernel extreme learning machine. Sensors 2017, 17, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magunov, A.N.; Pylnev, M.A.; Lapshinov, B.A. Spectral pyrometry of objects with unknown emissivities in a temperature range of 400–1200 K. Instrum. Exp. Tech. 2014, 57, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbroek, R.; Berenschot, J.; Jansen, H.; Nijdam, A.; Pandraud, G.; Berg, A.v.D.; Elwenspoek, M. Etching methodologies in〈111〉-oriented silicon wafers. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2000, 9, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscema, M. Back propagation neural networks. Subst. Use Misuse 1998, 33, 233–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cheng, J.-H.; Shi, J.-Y.; Huang, F. Brief introduction of back propagation (BP) neural network algorithm and its improvement. In Advances in Computer Science and Information Engineering: Volume 2; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 553–558. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Zhao, B.; Li, Q. The Research of Temperature Compensation for Thermopile Sensor Based on Improved PSO-BP Algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 854945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yao, B.; Huang, J.; Sun, S.; Zhang, F.; He, Z.; Tang, T.; Gao, R. Optimal temperature and humidity control for autonomous control system based on PSO-BP neural networks. IET Control Theory Appl. 2023, 17, 2097–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Xu, T.; Xia, H.; Xie, R.; Zhou, X.; Ge, X.; Liu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, L.; et al. Slowing hot-electron relaxation in mix-phase nanowires for hot-carrier photovoltaics. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 7761–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zeng, J.; Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Zheng, C.; Yi, J.; Liu, W.; Qu, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, W.; et al. High-Performance Silicon Nanowire Array Electronic Thermometer Fabricated Using CMOS-MEMS Techniques. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 9599–9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Zeng, J.; Yi, J.; Liu, W.; Qu, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, X.; et al. A CMOS-Compatible Silicon Nanowire Array Natural Light Photodetector with On-Chip Temperature Compensation Using a PSO-BP Neural Network. Micromachines 2026, 17, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010023

Liu M, Chen X, Zeng J, Yi J, Liu W, Qu X, Zhang J, Liu H, Liu C, Yang X, et al. A CMOS-Compatible Silicon Nanowire Array Natural Light Photodetector with On-Chip Temperature Compensation Using a PSO-BP Neural Network. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Mingbin, Xin Chen, Jiaye Zeng, Jintao Yi, Wenhe Liu, Xinjian Qu, Junsong Zhang, Haiyan Liu, Chaoran Liu, Xun Yang, and et al. 2026. "A CMOS-Compatible Silicon Nanowire Array Natural Light Photodetector with On-Chip Temperature Compensation Using a PSO-BP Neural Network" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010023

APA StyleLiu, M., Chen, X., Zeng, J., Yi, J., Liu, W., Qu, X., Zhang, J., Liu, H., Liu, C., Yang, X., & Huang, K. (2026). A CMOS-Compatible Silicon Nanowire Array Natural Light Photodetector with On-Chip Temperature Compensation Using a PSO-BP Neural Network. Micromachines, 17(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010023