Parameter Estimation and Quantification of Magnetic Nanoparticles Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Relaxation Theory Models and Parameter Estimation Methods

2.1.1. Relaxation Mechanisms of Magnetic Nanoparticles

2.1.2. Magnetic Relaxation Data Simulation Model

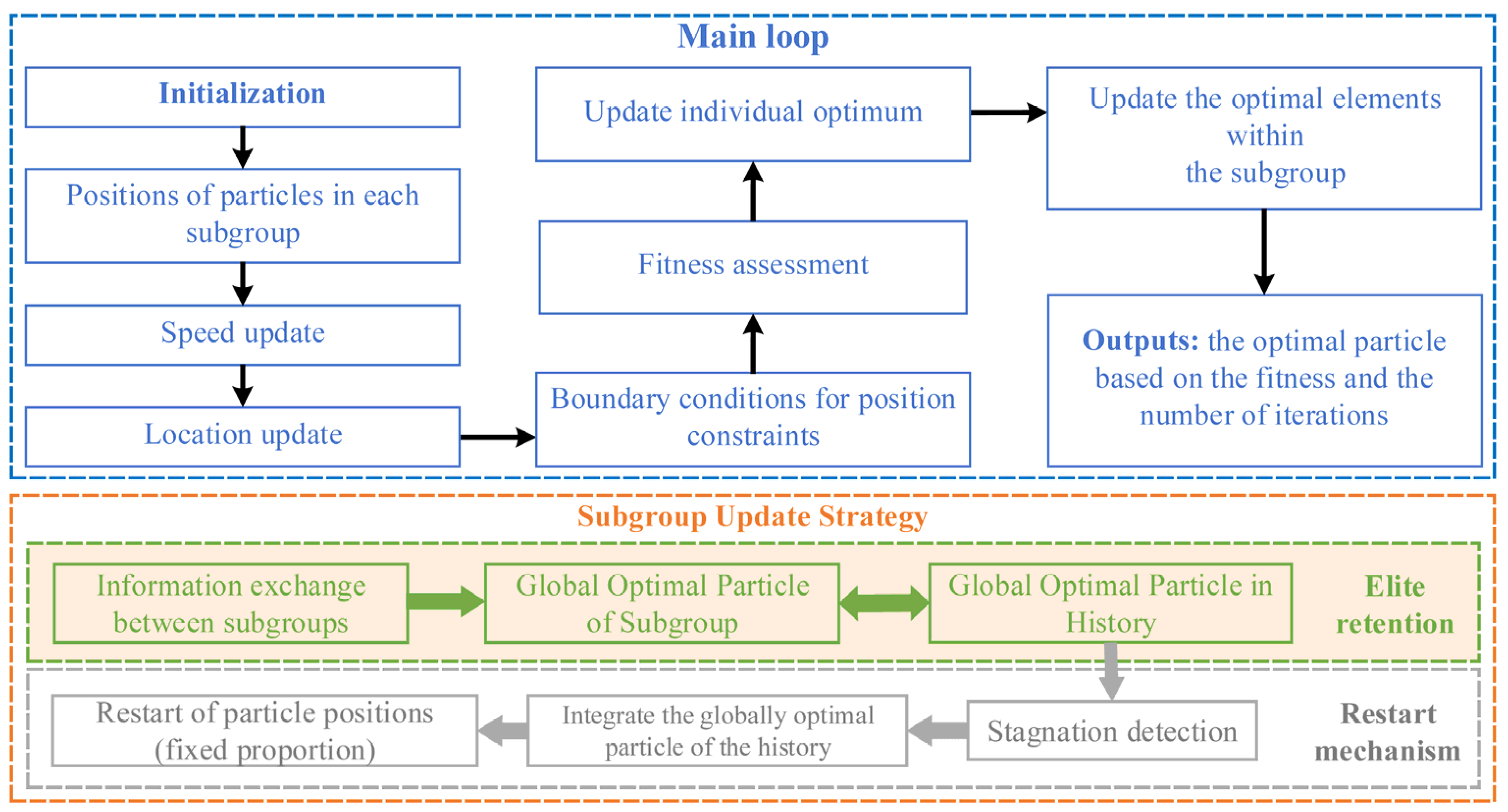

2.1.3. Improved Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm

- Multiple Subgroups: Several subgroups are formed, with each subgroup independently performing particle updates within the main PSO loop. The particle update process is conducted under boundary constraints, producing both the individual best positions for each particle and the global best position of the subgroup;

- Elite preservation mechanism: During the iterations, subgroups exchange information to determine the global best particle across all subgroups. The first updated global best particle is used as the initial historical global best particle. In subsequent iterations, the global best particle obtained in the current iteration is compared with that of the previous iteration. If the current global best particle yields a smaller objective function value, it replaces the previous one as the new historical global best particle. A predefined number of historical global best particles is maintained, and at each iteration, no more than this number of particles can be updated;

- Stagnation-restart mechanism: A maximum stagnation iteration threshold is first defined. If the historical global best particle is not updated within this number of iterations, a fixed proportion of particles in each subgroup is re-initialized. The restart procedure ensures that the current historical global best particle is preserved within each subgroup while maintaining inter-subgroup information exchange. A ring topology is adopted for inter-subgroup communication, where subgroups are arranged sequentially, and the best particle from a neighboring subgroup is used to influence the particles of the current subgroup through mutation. In this article, the mutation probability in the subgroup information exchange is set to a random value not exceeding 20%. Specifically, a mutation vector is added to the position of each subgroup’s global best particle, which is calculated as the product of a random probability and the difference between the global best particles of adjacent subgroups. This mechanism effectively mitigates stagnation by introducing controlled diversity while retaining superior solutions.

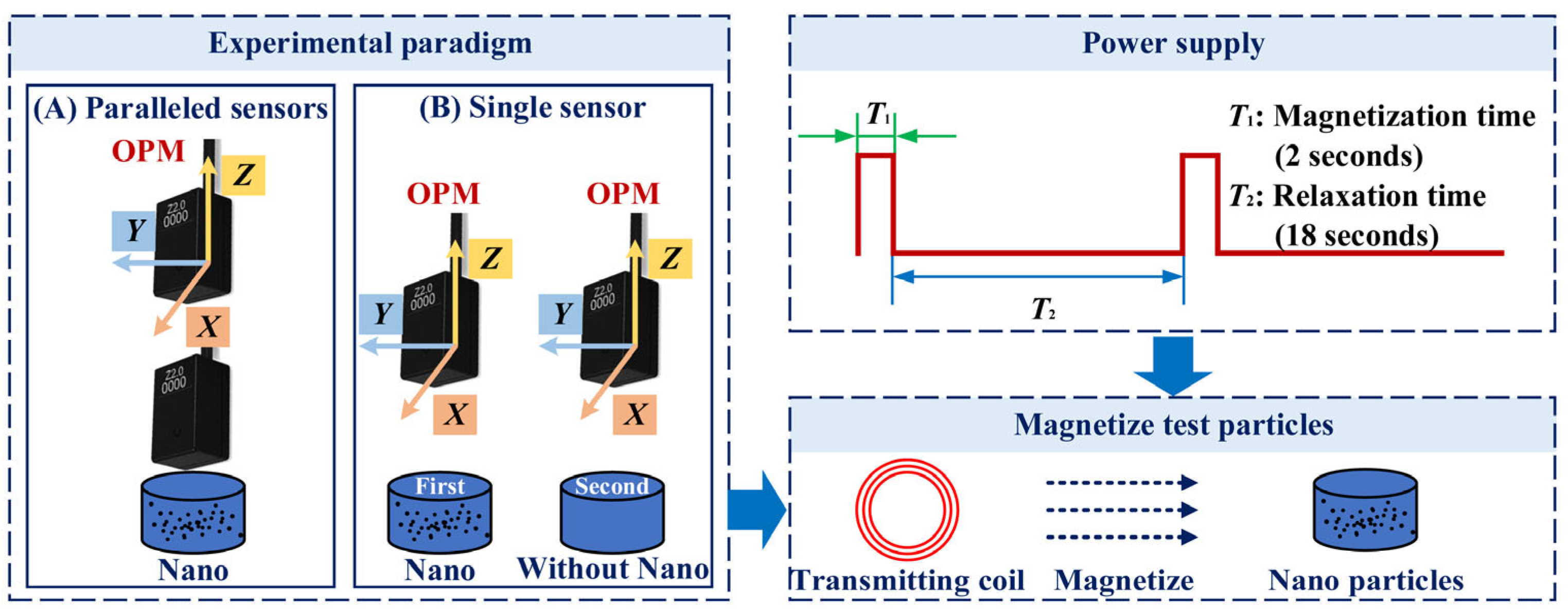

2.2. Experiment Setup

2.2.1. Measurement by OPM

2.2.2. Magnetization Devices and Control Equipment

2.2.3. Signal Acquisition and Processing

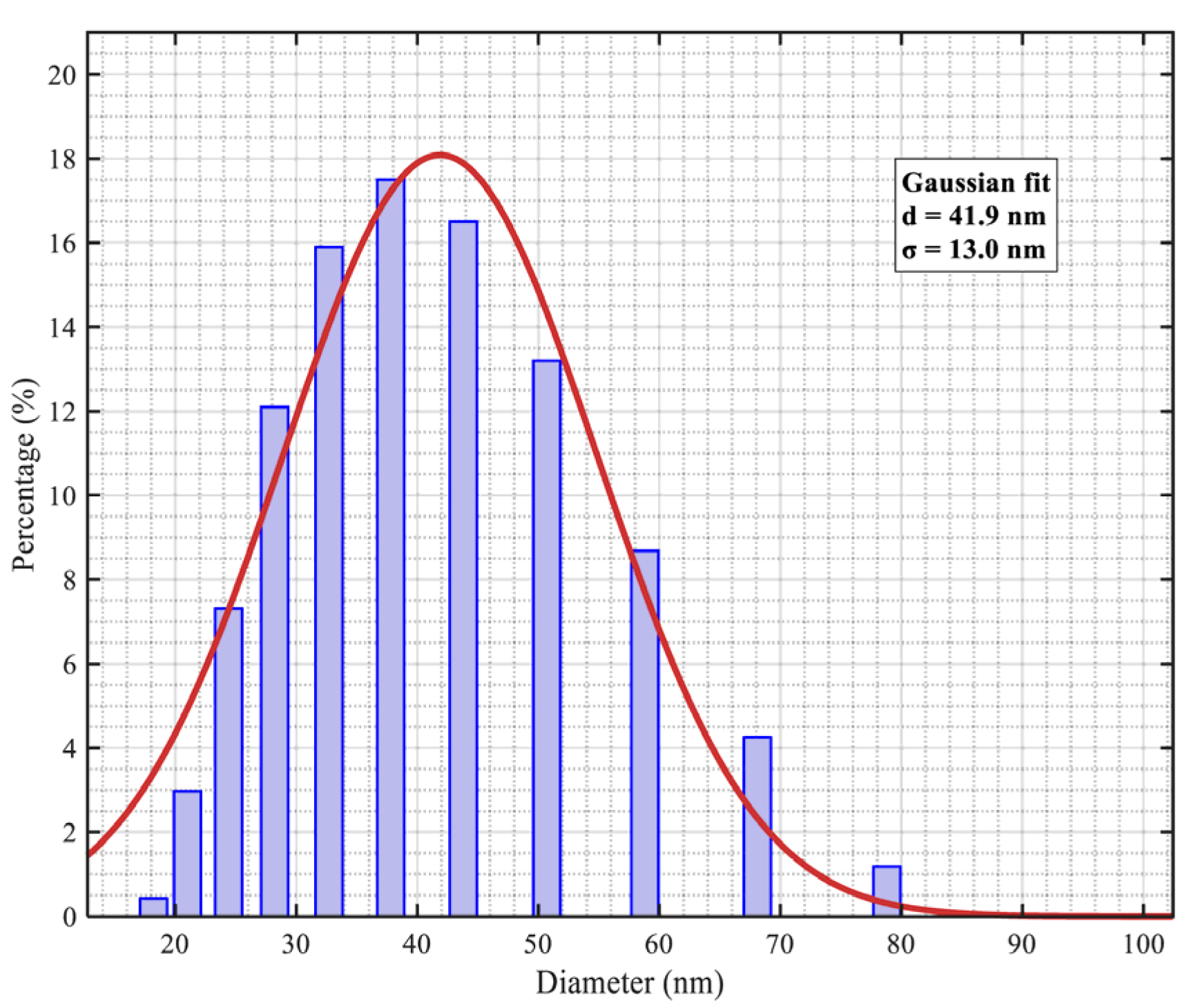

2.2.4. Characterization of Magnetic Nanoparticles

3. Results

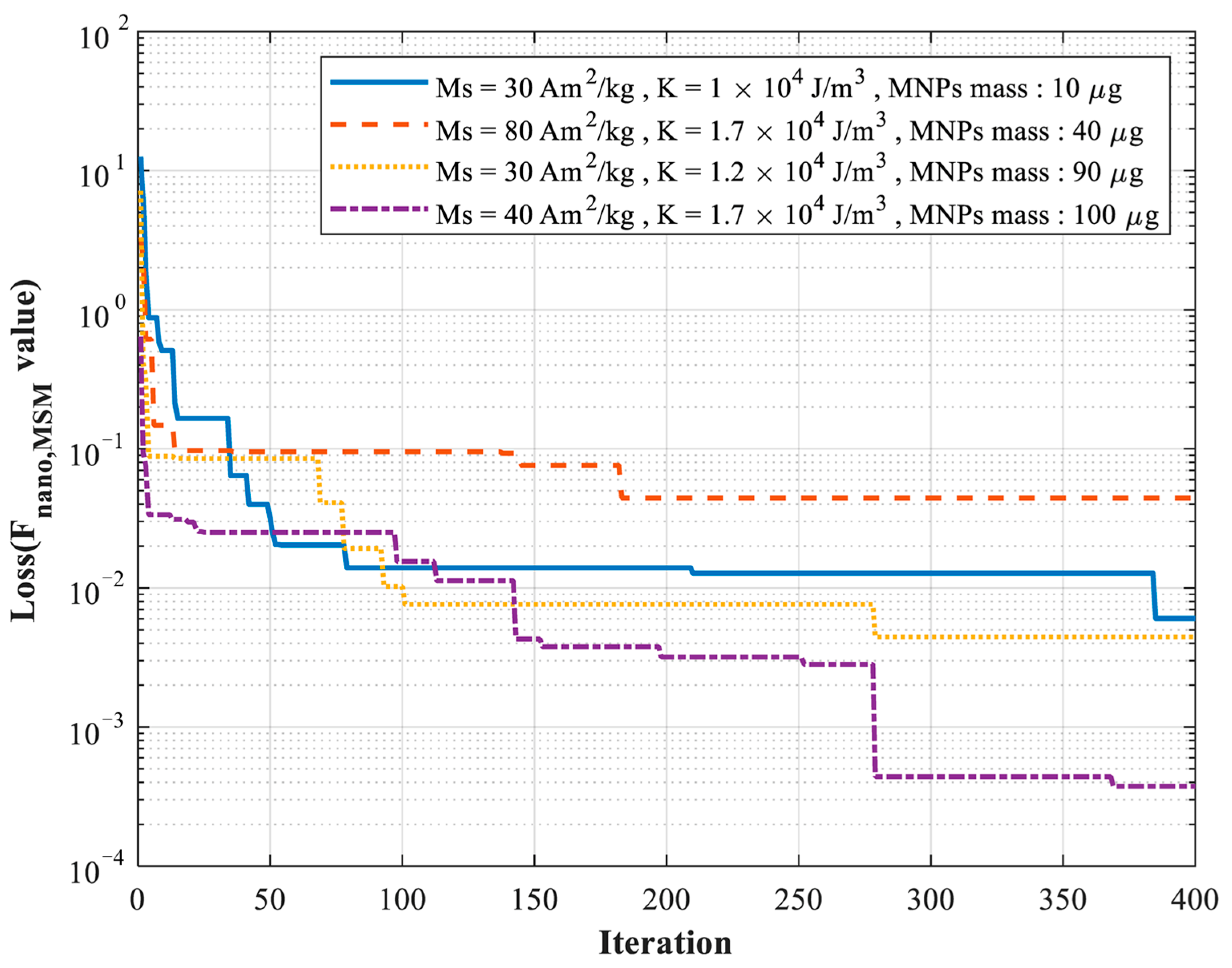

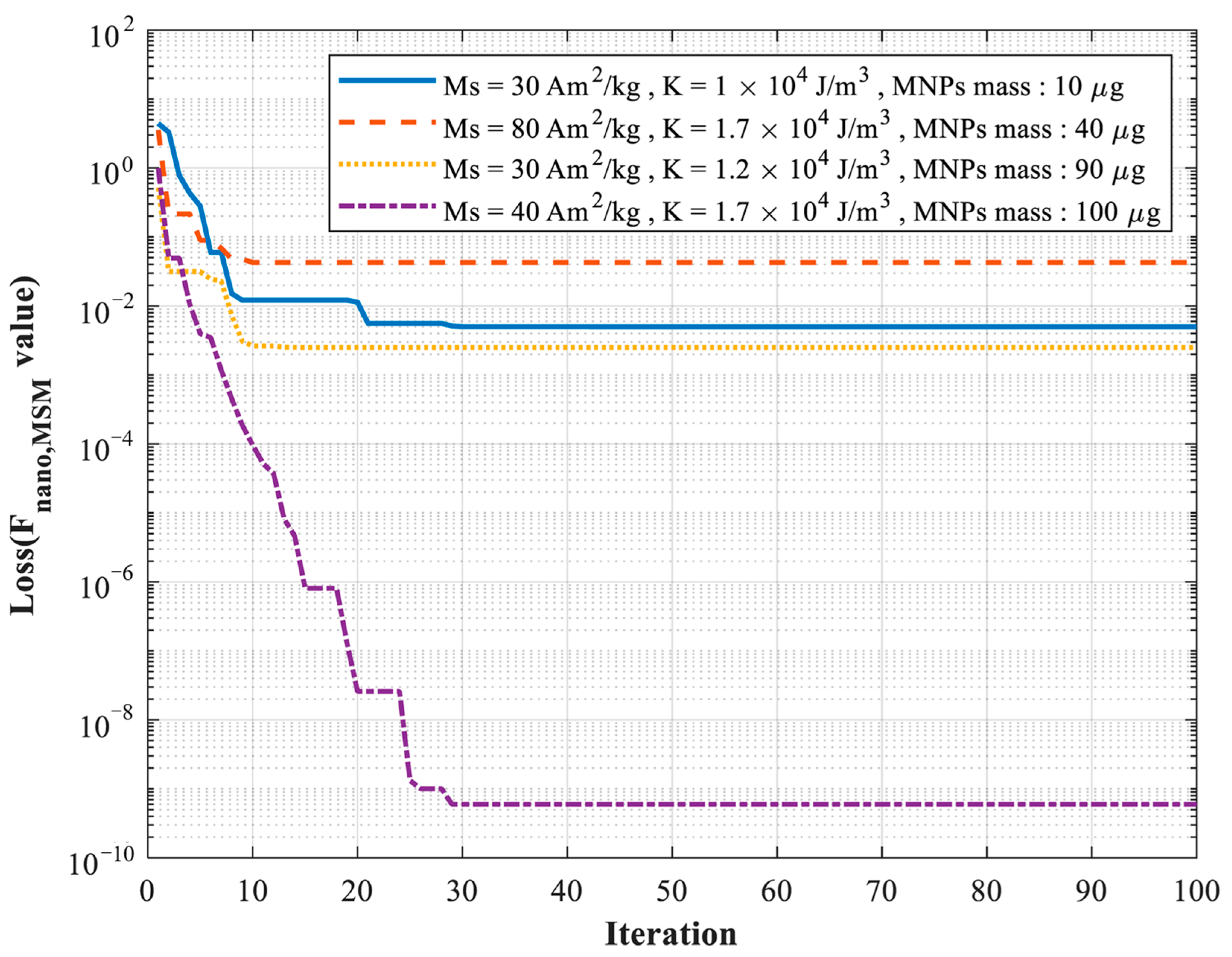

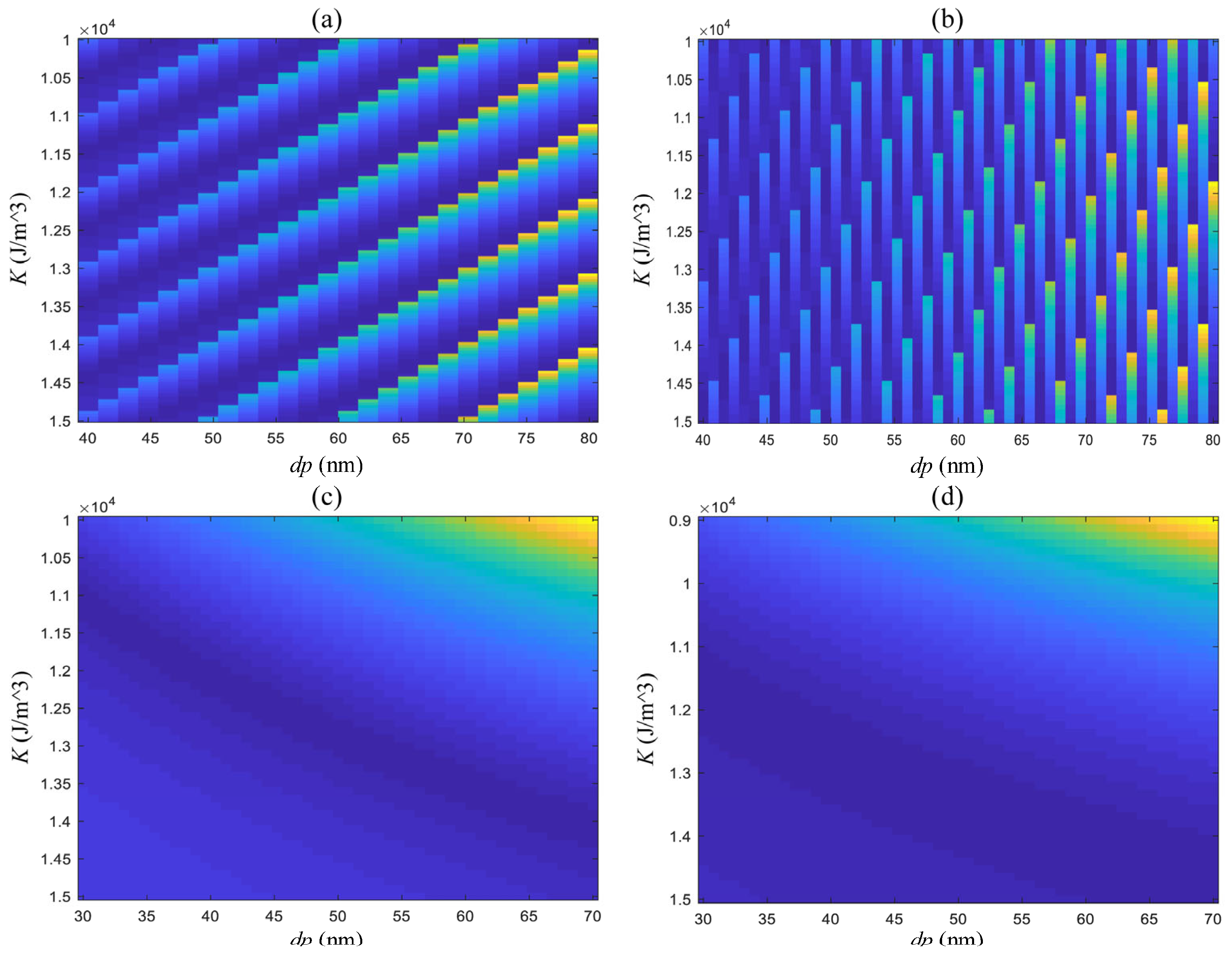

3.1. Simulation Validation

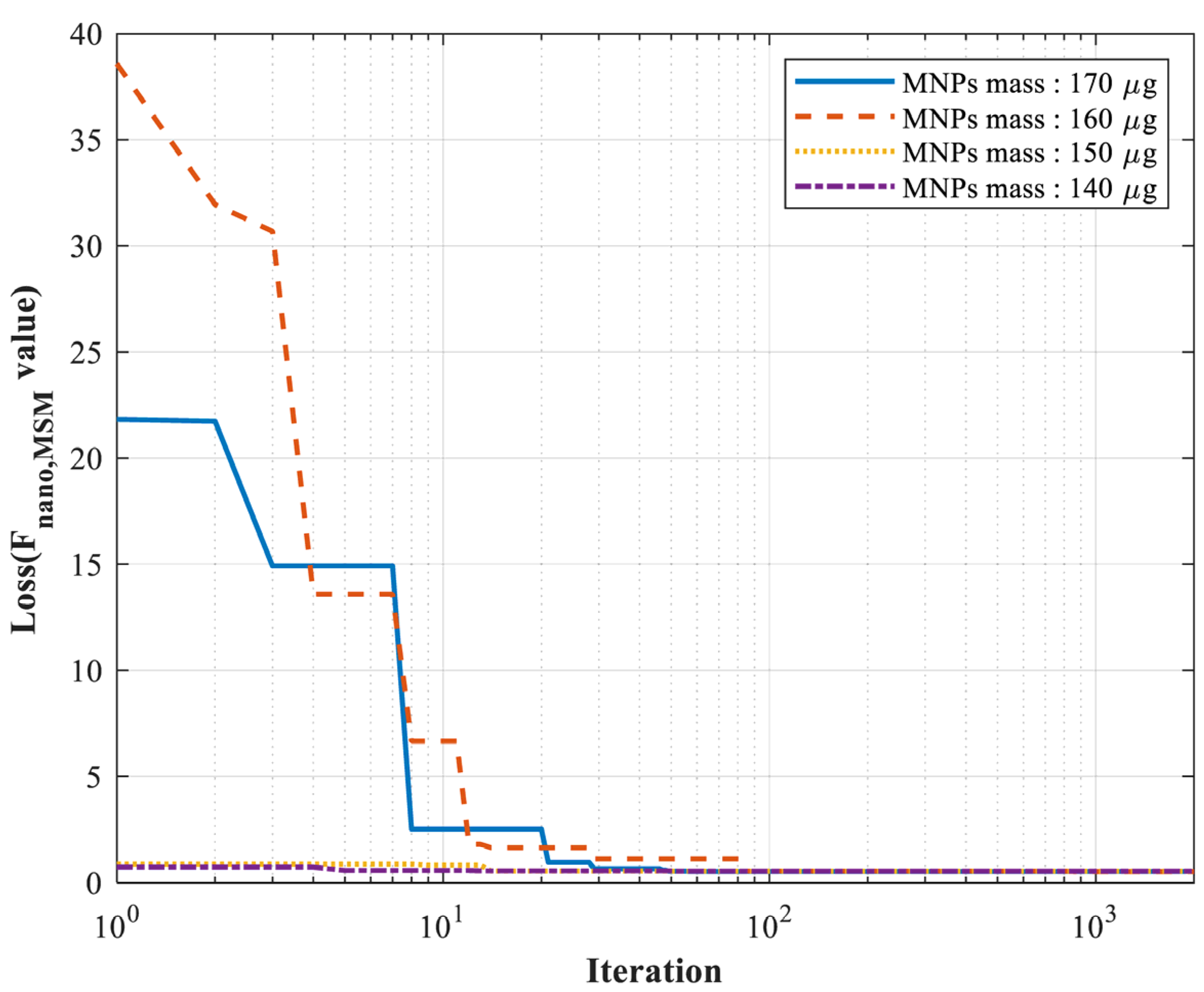

3.2. Analysis of Measured Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Huang, B.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Zhai, Y. Flow rate estimation based on magnetic particle detection using a miniatured high-sensitivity OPM. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. Meas. 2025, 74, 3565069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiekhorst, F.; Steinhoff, U.; Eberbeck, D.; Trahms, L. Magnetorelaxometry assisting biomedical applications of magnetic nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolphi, N.L.; Huber, D.L.; Jaetao, J.E.; Bryant, H.C.; Lovato, D.M.; Fegan, D.L.; Venturini, E.L.; Monson, T.C.; Tessier, T.E.; Hathaway, H.J.; et al. Characterization of magnetite nanoparticles for SQUID-relaxometry and magnetic needle biopsy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009, 321, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öisjöen, F.; Schneiderman, J.F.; Prieto Astalan, A.; Kalabukhov, A.; Johansson, C.; Winkler, D. A new approach for bioassays based on frequency-and time-domain measurements of magnetic nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 25, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, E.; Bryant, H. A biomagnetic system for in vivo cancer imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005, 50, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, H.; Kettering, M.; Wiekhorst, F.; Steinhoff, U.; Hilger, I.; Trahms, L. Magnetorelaxometry for localization and quantification of magnetic nanoparticles for thermal ablation studies. Phys. Med. Biol. 2010, 55, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haro, L.P.; Karaulanov, T.; Vreeland, E.C.; Anderson, B.; Hathaway, H.J.; Huber, D.L.; Matlashov, A.N.; Nettles, C.P.; Price, A.D.; Monson, T.C.; et al. Magnetic relaxometry as applied to sensitive cancer detection and localization. Biomed. Eng. Biomed. Technik. 2015, 60, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolphi, N.L.; Butler, K.S.; Lovato, D.M.; Tessier, T.E.; Trujillo, J.E.; Hathaway, H.J.; Fegan, D.L.; Monson, T.C.; Stevens, T.E.; Huber, D.L.; et al. Imaging of Her2-targeted magnetic nanoparticles for breast cancer detection: Comparison of SQUID-detected magnetic relaxometry and MRI. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2012, 7, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebl, M.; Steinhoff, U.; Wiekhorst, F.; Haueisen, J.; Trahms, L. Quantitative imaging of magnetic nanoparticles by magnetorelaxometry with multiple excitation coils. Phys. Med. Biol. 2014, 59, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebl, M.; Steinhoff, U.; Wiekhorst, F.; Coene, A.; Haueisen, J.; Trahms, L. Quantitative reconstruction of a magnetic nanoparticle distribution using a non-negativity constraint. Biomed. Eng. Biomed. Technik. 2013, 58, 000010151520134261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schambach, J.; Warzemann, L.; Weber, P.; Kotitz, R.; Weitschies, W. SQUID gradiometer measurement system for magnetorelaxometry in a disturbed environment. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 1999, 9, 3527–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebl, M.; Wiekhorst, F.; Eberbeck, D.; Radon, P.; Gutkelch, D.; Baumgarten, D.; Steinhoff, U.; Trahms, L. Magnetorelaxometry procedures for quantitative imaging and characterization of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Biomed. Eng. Biomed. Technik. 2015, 60, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coene, A.; Leliaert, J.; Liebl, M.; Löwa, N.; Steinhoff, U.; Crevecoeur, G.; Dupré, L.; Wiekhorst, F. Multi-color magnetic nanoparticle imaging using magnetorelaxometry. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supek, S.; Aine, C. Magnetoencephalography; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baffa, O.; Matsuda, R.; Arsalani, S.; Prospero, A.; Miranda, J.; Wakai, R. Development of an optical pumped gradiometric system to detect magnetic relaxation of magnetic nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 475, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaufenthaler, A.; Schultze, V.; Scholtes, T.; Schmidt, C.B.; Handler, M.; Stolz, R.; Baumgarten, D. OPM magnetorelaxometry in the presence of a DC bias field. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2020, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaufenthaler, A.; Kornack, T.; Lebedev, V.; Limes, M.E.; Körber, R.; Liebl, M.; Baumgarten, D. Pulsed optically pumped magnetometers: Addressing dead time and bandwidth for the unshielded magnetorelaxometry of magnetic nanoparticles. Sensors 2021, 21, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y.; He, X.; Ruan, L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Weng, J.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, G.; Li, K.; Zheng, W.; et al. Drug monitoring by optically pumped atomic magnetometer. IEEE Photonics J. 2022, 14, 3134305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, A.G.; Costo, R.; Rebolledo, A.F.; Veintemillas-Verdaguer, S.; Tartaj, P.; González-Carreño, T.; Morales, M.P.; Serna, C.J. Progress in the preparation of magnetic nanoparticles for applications in biomedicine. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 224002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgovskiy, V.; Lebedev, V.; Colombo, S.; Weis, A.; Michen, B.; Ackermann-Hirschi, L.; Petri-Fink, A. A quantitative study of particle size effects in the magnetorelaxometry of magnetic nanoparticles using atomic magnetometry. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 379, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantrell, R.; Hoon, S.; Tanner, B. Time-dependent magnetization in fine-particle ferromagnetic systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1983, 38, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberbeck, D.; Hartwig, S.; Steinhoff, U.; Trahms, L. Description of the magnetization decay in ferrofluids with a narrow particle size distribution. Magnetohydrodynamics 2003, 39, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Eberbeck, D.; Wiekhorst, F.; Steinhoff, U.; Trahms, L. Aggregation behaviour of magnetic nanoparticle suspensions investigated by magnetorelaxometry. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, S2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiekhorst, F.; Eberbeck, D.; Steinhoff, U.; Gutkelch, D.; Trahms, L. SQUID-basierte Magnetrelaxometrie an magnetischen Nanopartikeln für die medizinische Diagnostik. Abschlussbericht BMBF-Verbundvorhaben Nanomagnetomedizin. Available online: https://edocs.tib.eu/files/e01fb08/576714585l.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Ludwig, F.; Heim, E.; Schilling, M.; Enpuku, K. Characterization of superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles by fluxgate magnetorelax-ometry for use in biomedical applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 07A314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolphi, N.L.; Huber, D.L.; Bryant, H.C.; Monson, T.C.; Fegan, D.L.; Lim, J.; Trujillo, J.E.; Tessier, T.E.; Lovato, D.M.; Butler, K.S.; et al. Characterization of single-core magnetite nanoparticles for magnetic imaging by SQUID relaxometry. Phys. Med. Biol. 2010, 55, 5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Anderson, B.; Huang, C.; Kunde, G.J.; Vreeland, E.C.; Huang, J.W.; Matlashov, A.N.; Karaulanov, T.; Nettles, C.P.; Gomez, A.; et al. Development of advanced signal processing and source imaging methods for superparamagnetic relaxometry. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, W.; Mathieu, K.; Thrower, S.; Fuentes, D.; Kaffes, C.; Sovizi, J.; Hazle, J.D. Automated algorithms for improved pre-processing of magnetic relaxometry data. In Medical Imaging 2018: Physics of Medical Imaging; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; Volume 10573, pp. 962–969. [Google Scholar]

- Thrower, S. A Compressed Sensing Approach to Detect Immobilized Nanoparticles Using Superparamagnetic Relaxometry. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas, Houston, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, F.; Heim, E.; Schilling, M. Characterization of superparamagnetic nanoparticles by analyzing the magnetization and relaxation dynamics using fluxgate magnetometers. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 113909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyakhman, F.; Safronov, A.; Starodumov, I.; Kuznetsova, D.; Kurlyandskaya, G. Remote Positioning of Spherical Alginate Ferrogels in a Fluid Flow by a Magnetic Field: Experimental and Computer Simulation. Gels 2023, 9, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95—International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November 27–1 December 1995; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1995; Volume 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. A modified particle swarm optimizer. In Proceedings of the IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence, Anchorage, Alaska, 4–9 May 1998; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, S.A.M.K.; Ficiarà, E.; Ruffinatti, F.A.; Stura, I.; Argenziano, M.; Abollino, O.; Cavalli, R.; Guiot, C.; D’agata, F. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Functionalization for Biomedical Applications in the Central Nervous System. Materials 2019, 12, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, G.; Celegato, F.; Vassallo, M.; Martella, D.; Coïsson, M.; Olivetti, E.S.; Martino, L.; Sözeri, H.; Manzin, A.; Tiberto, P. Microfluidic Detection of SPIONs and Co-Ferrite Ferrofluid Using Amorphous Wire Magneto-Impedance Sensor. Sensors 2024, 24, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 3 | Trial 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real K (×104 J/m3) | 1 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| Estimated K (×104 J/m3) | 1.015 | 1.693 | 1.236 | 1.710 |

| Real MS (Am2/kg) | 30 | 80 | 30 | 40 |

| Estimated MS (Am2/kg) | 31.419 | 78.811 | 29.815 | 41.042 |

| Real MNPs mass (μg) | 10 | 40 | 90 | 100 |

| Estimated MNPs mass (μg) | 9.99 | 39.99 | 89.97 | 100.01 |

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 3 | Trial 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated K (×104 J/m3) | 1.640 | 1.631 | 1.646 | 1.612 |

| Estimated MS (Am2/kg) | 60.334 | 59.682 | 63.271 | 61.131 |

| Real MNPs mass (μg) | 170 | 160 | 150 | 140 |

| Estimated MNPs mass (μg) | 169.95 | 159.84 | 149.48 | 140.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Ning, X. Parameter Estimation and Quantification of Magnetic Nanoparticles Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization. Micromachines 2026, 17, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010022

Wu H, Yu H, Chen X, Gao Y, Ning X. Parameter Estimation and Quantification of Magnetic Nanoparticles Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Huangliang, Hang Yu, Xiaoyu Chen, Yang Gao, and Xiaolin Ning. 2026. "Parameter Estimation and Quantification of Magnetic Nanoparticles Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010022

APA StyleWu, H., Yu, H., Chen, X., Gao, Y., & Ning, X. (2026). Parameter Estimation and Quantification of Magnetic Nanoparticles Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization. Micromachines, 17(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010022