Enhanced Efficiency and Reliability of AlGaN UVC-LED with Tapered Hole Injection Layer

Abstract

1. Introduction

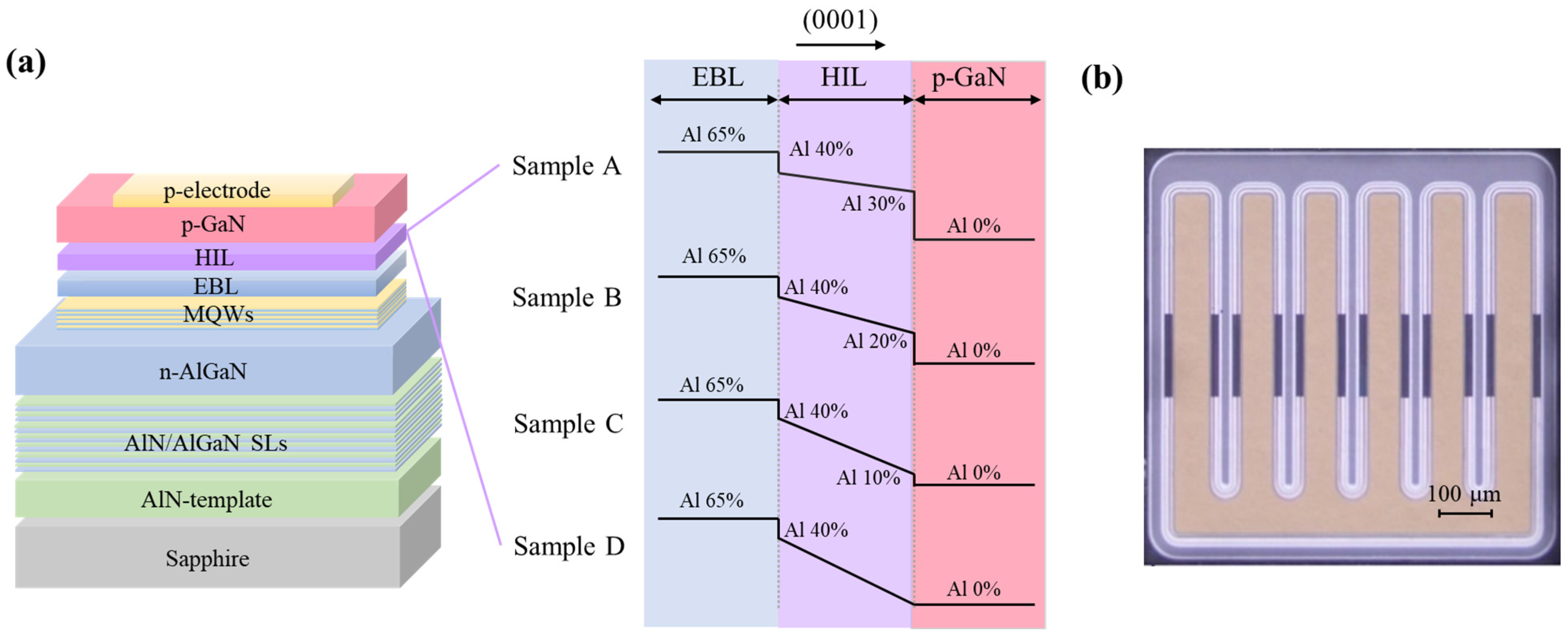

2. Experiment Details

2.1. Device Fabrication

2.2. Characterization

2.3. Numerical Investigation

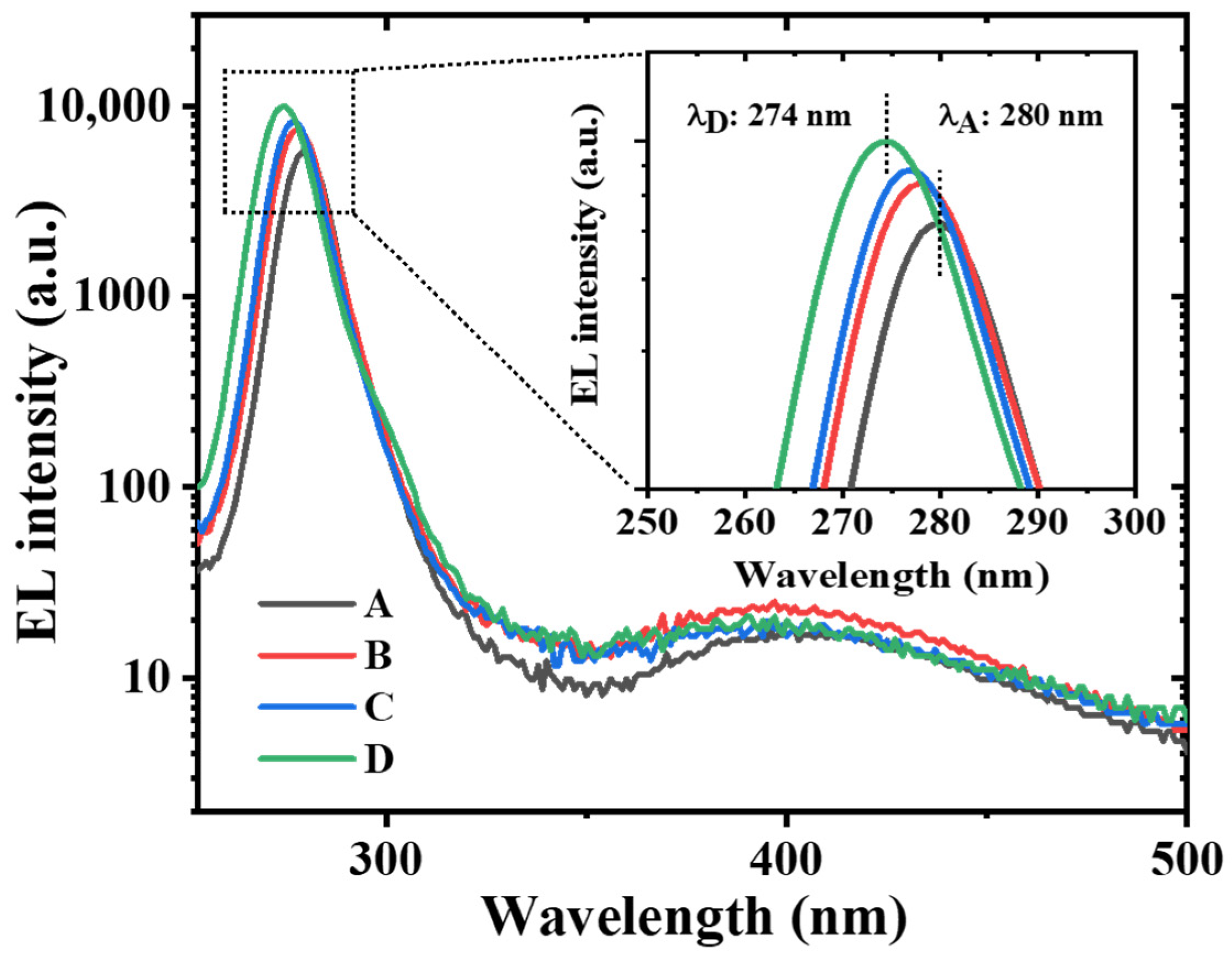

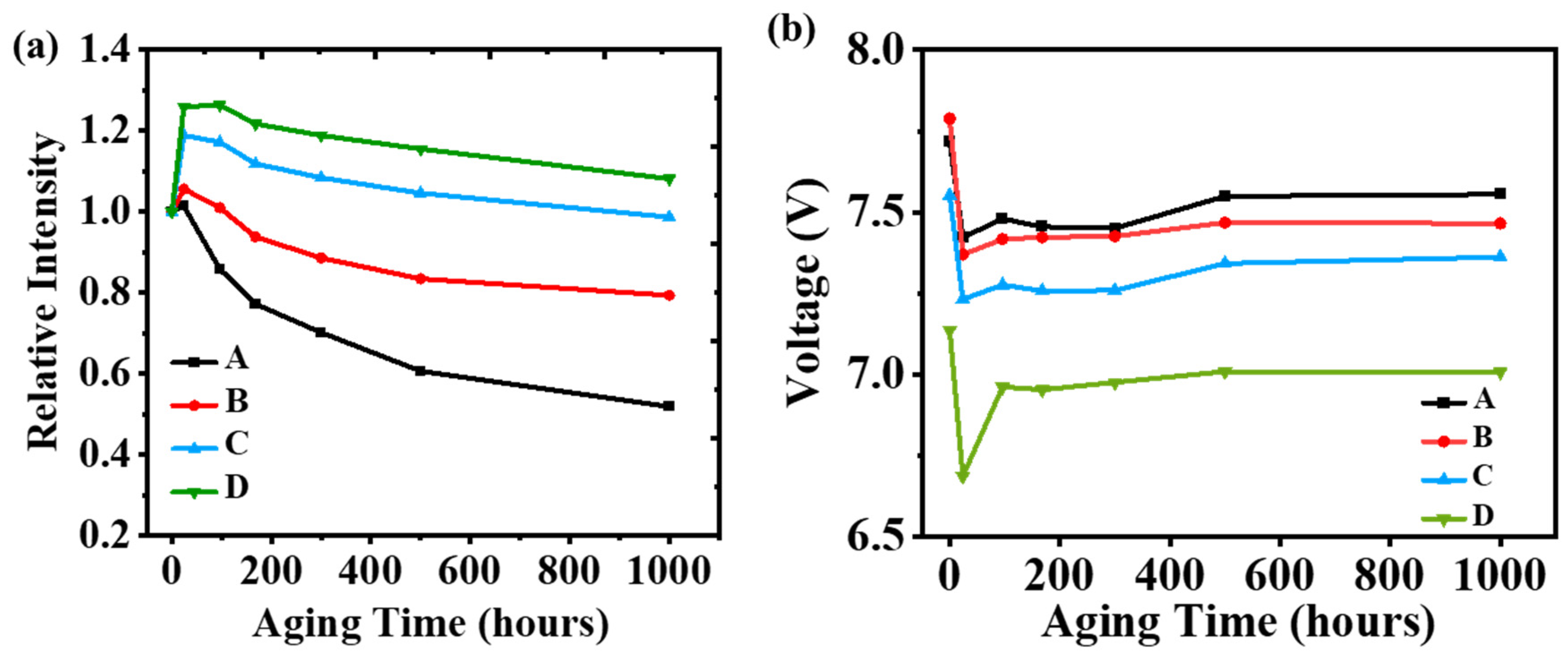

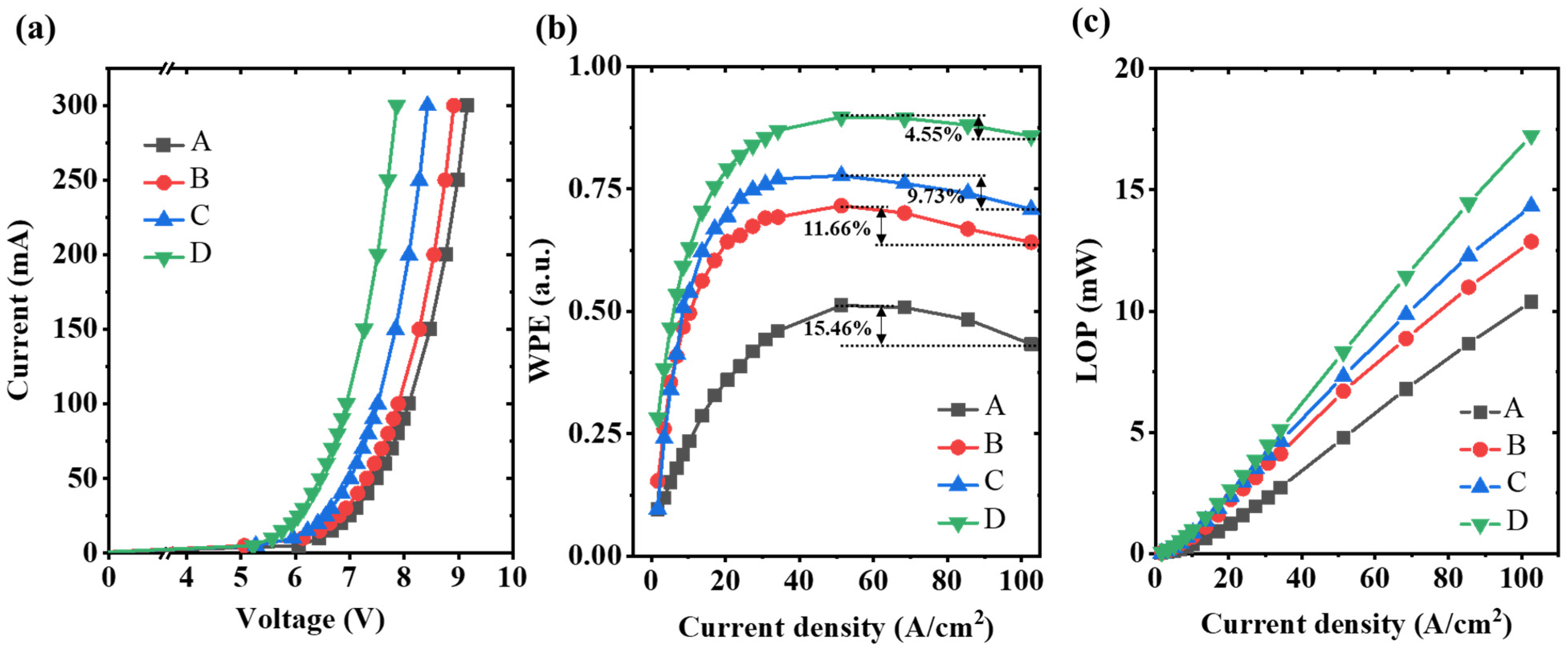

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, G.; Tao, X.; Pan, T.; Chen, Z.; Cai, Q.; Shao, P.; Yang, G.; Huang, Z.; et al. Multiple exciton generation boosting over 100% quantum efficiency photoelectrochemical photodetection. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Dai, S.; Chu, C.; Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Ling, F.C.-C.; Yang, G. Synaptic solar-blind UV PD based on STO/AlXGa1−XN heterostructure for neuromorphic computing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 142105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z. Review of the AlGaN/GaN High-Electron-Mobility Transistor-Based Biosensors: Structure, Mechanisms, and Applications. Micromachines 2024, 15, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, B.; Ge, M.; Wang, X.; Ye, B.; Nikolaevna Parkhomenko, I.; Fadeevich Komarov, F.; Wang, J.; Xue, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, G. AlGaN/GaN HEMT-Based MHM Ultraviolet Phototransistor With Bent-Gate Structure. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2024, 45, 2335–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yang, H.; Hyun, B.-R.; Xu, K.; Kwok, H.-S.; Liu, Z. High-power AlGaN deep-ultraviolet micro-light-emitting diode displays for maskless photolithography. Nat. Photonics 2024, 19, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneissl, M.; Seong, T.-Y.; Han, J.; Amano, H. The emergence and prospects of deep-ultraviolet light-emitting diode technologies. Nat. Photonics 2019, 13, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ben, J.; Xu, F.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, D. Review on the Progress of AlGaN-based Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes. Fundam. Res. 2021, 1, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Jian, P.; Shan, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, D.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; et al. Tunable structured AlGaN-based nanoporous distributed Bragg reflectors for light-coupling enhancement in monolayer MoS2. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 172, 110508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Xu, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, X.; Ji, C.; Ji, C.; Tan, F.; et al. Progress in Performance of AlGaN-Based Ultraviolet Light Emitting Diodes. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2024, 11, 2300840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Hao, X.; Zeng, J.; Li, L.; Wang, P.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L.; Shi, F.; Wu, Y. Research progress of alkaline earth metal iron-based oxides as anodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Semicond. 2024, 45, 021801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveless, J.; Kirste, R.; Moody, B.; Reddy, P.; Rathkanthiwar, S.; Almeter, J.; Collazo, R.; Sitar, Z. Performance and reliability of state-of-the-art commercial UVC light emitting diodes. Solid-State Electron. 2023, 209, 108775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jiang, K.; Sun, X.; Guo, C. AlGaN photonics: Recent advances in materials and ultraviolet devices. Adv. Opt. Photonics 2018, 10, 43–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Chen, Q.; Dai, J.; Wang, A.; Liang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, M.; Wu, F.; Zhang, W.; Chen, C.; et al. Enhanced light extraction efficiency via double nano-pattern arrays for high-efficiency deep UV LEDs. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 143, 107360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velpula, R.T.; Jain, B.; Velpula, S.; Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, H.P.T. High-performance electron-blocking-layer-free deep ultraviolet light-emitting diodes implementing a strip-in-a-barrier structure. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 5125–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Mitra, S.; Subedi, R.C.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, W.; Ye, J.; Shakfa, M.K.; Ng, T.K.; Ooi, B.S.; Roqan, I.S.; et al. Unambiguously Enhanced Ultraviolet Luminescence of AlGaN Wavy Quantum Well Structures Grown on Large Misoriented Sapphire Substrate. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1905445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Cao, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, J.; Yang, T.; Mi, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Liu, J. Performance Improvement of AlGaN-Based Deep-Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes with Multigradient Electron Blocking Layer and Triangular Last Quantum Barrier. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2023, 220, 2300192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, R.K.; Chatterjee, V.; Pal, S. Efficient Carrier Transport for AlGaN-Based Deep-UV LEDs With Graded Superlattice p-AlGaN. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2020, 67, 1674–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Zhang, L.; Niu, Y.; Yu, J.; Ma, H.; Yang, S.; Zuo, C.; Qian, H.; Duan, B.; Zhang, B.; et al. High Hole Injection for Nitrogen-Polarity AlGaN-Based Deep-Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2023, 44, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, J.; Shao, H.; Chang, L.; Kou, J.; Tian, K.; Chu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, W.; Zhang, Z.-H. Doping-induced energy barriers to improve the current spreading effect for AlGaN-based ultraviolet-B light-emitting diodes. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2020, 41, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Tian, W.; Liu, M.; Li, S.; Liu, C. Enhancing the Hole Injection in AlGaN-Based Deep Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes With Engineered p-AlGaN Hole Supplier Layer. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2024, 71, 3077–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chu, C.; Jia, T.; Jia, Y.; Tian, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.-H. Is It Possible to Make Thin p-GaN Layer for AlGaN-Based Deep Ultraviolet Micro Light Emitting Diodes? IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2024, 45, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shen, M.-C.; Lai, S.; Dai, Y.; Chen, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, L.; Chen, G.; Lin, S.-H.; Peng, K.-W.; et al. Impacts of p-GaN layer thickness on the photoelectric and thermal performance of AlGaN-based deep-UV LEDs. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 36547–36556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-H.; Huang Chen, S.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, S.-W.; Tian, K.; Chu, C.; Fang, M.; Kuo, H.-C.; Bi, W. Hole Transport Manipulation To Improve the Hole Injection for Deep Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Diodes. ACS Photonics 2017, 4, 1846–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhao, S. Improving Charge Carrier Transport Properties in AlGaN Deep Ultraviolet Light Emitters Using Al-Content Engineered Superlattice Electron Blocking Layer. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2023, 59, 3300106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccato, N.; Piva, F.; Buffolo, M.; De Santi, C.; Trivellin, N.; Susilo, N.; Vidal, D.H.; Muhin, A.; Sulmoni, L.; Wernicke, T.; et al. Diffusion mechanism as cause of optical degradation in AlGaN-based UV-C leds investigated by TCAD simulations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 39655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Sun, X.; Lei, C.; Liang, T.; Li, F.; Xie, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, N. Study on the Degradation Performance of AlGaN-Based Deep Ultraviolet LEDs under Thermal and Electrical Stress. Coatings 2024, 14, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, A.; Shan, M.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Wu, F.; Dai, J.; et al. Full wafer scale electroluminescence properties of AlGaN-based deep ultraviolet LEDs with different well widths. Opt Lett 2021, 46, 2111–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.L.; Chang, C.S. A band-structure model of strained quantum-well wurtzite semiconductors. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 1997, 12, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Long, H.; Dai, J.; Zhang, Z.-h.; Chen, C. Improved the AlGaN-Based Ultraviolet LEDs Performance With Super-Lattice Structure Last Barrier. IEEE Photonics J. 2018, 10, 8201007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhao, L.; Cao, H.; Sun, X.; Sun, B.; Wang, J.; Li, J. Degradation and corresponding failure mechanism for GaN-based LEDs. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 055219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaab, J.; Haefke, J.; Ruschel, J.; Brendel, M.; Rass, J.; Kolbe, T.; Knauer, A.; Weyers, M.; Einfeldt, S.; Guttmann, M.; et al. Degradation effects of the active region in UV-C light-emitting diodes. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piva, F.; De Santi, C.; Deki, M.; Kushimoto, M.; Amano, H.; Tomozawa, H.; Shibata, N.; Meneghesso, G.; Zanoni, E.; Meneghini, M. Modeling the degradation mechanisms of AlGaN-based UV-C LEDs: From injection efficiency to mid-gap state generation. Photonics Res. 2020, 8, 1786–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Peng, Y.; Wu, F.; Guo, W.; Dai, J.; Chen, C. Enhanced Efficiency and Reliability of AlGaN UVC-LED with Tapered Hole Injection Layer. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121376

Xu L, Peng Y, Wu F, Guo W, Dai J, Chen C. Enhanced Efficiency and Reliability of AlGaN UVC-LED with Tapered Hole Injection Layer. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121376

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Linlin, Yang Peng, Feng Wu, Wei Guo, Jiangnan Dai, and Changqing Chen. 2025. "Enhanced Efficiency and Reliability of AlGaN UVC-LED with Tapered Hole Injection Layer" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121376

APA StyleXu, L., Peng, Y., Wu, F., Guo, W., Dai, J., & Chen, C. (2025). Enhanced Efficiency and Reliability of AlGaN UVC-LED with Tapered Hole Injection Layer. Micromachines, 16(12), 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121376