Examination of Impact of NBTIs on Commercial Power P-Channel VDMOS Transistors in Practical Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

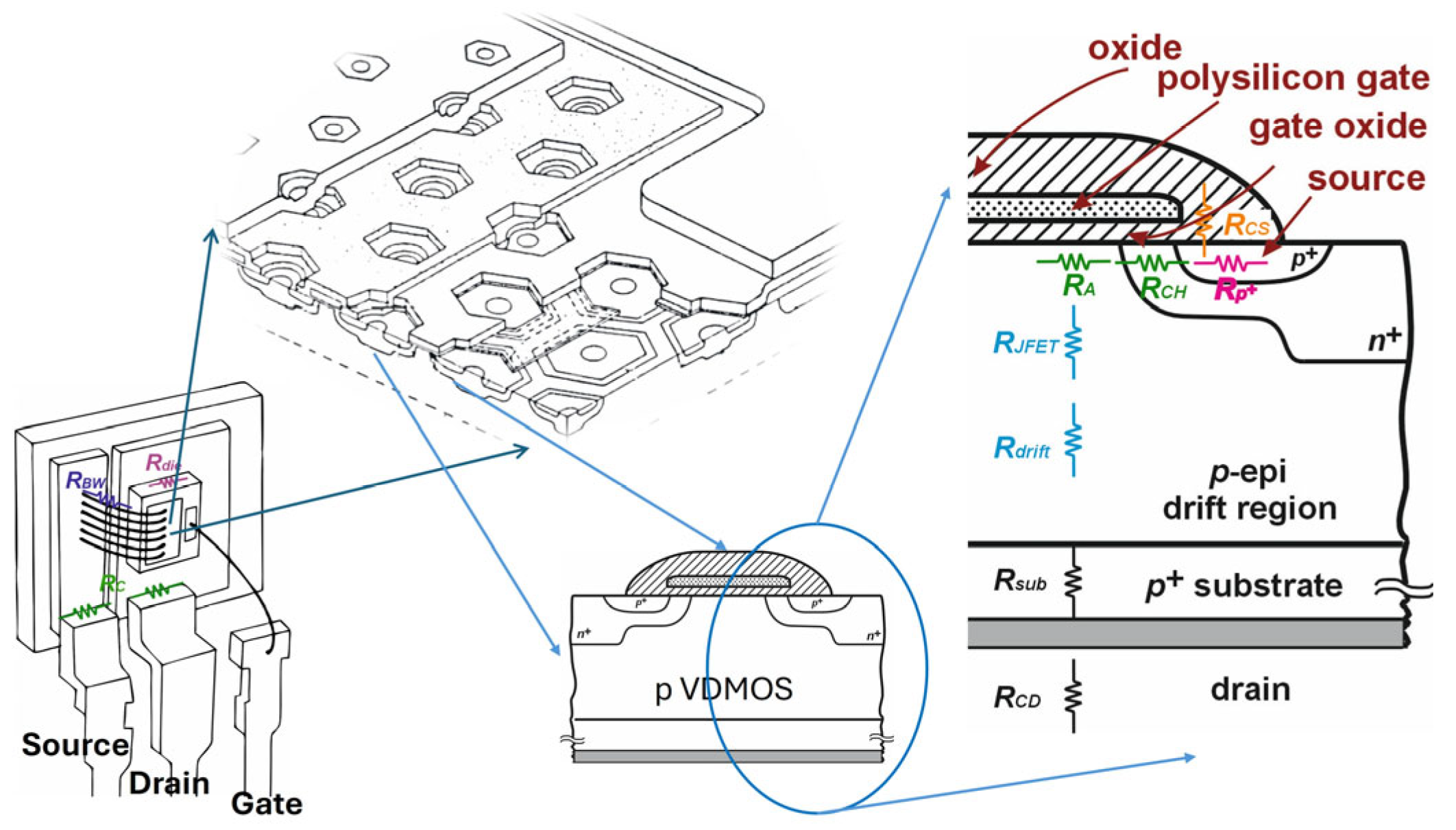

1.1. Effect of Negative Bias Temperature Instabilities

1.2. Self-Heating Effects

1.3. Impact on the Circuit Performance

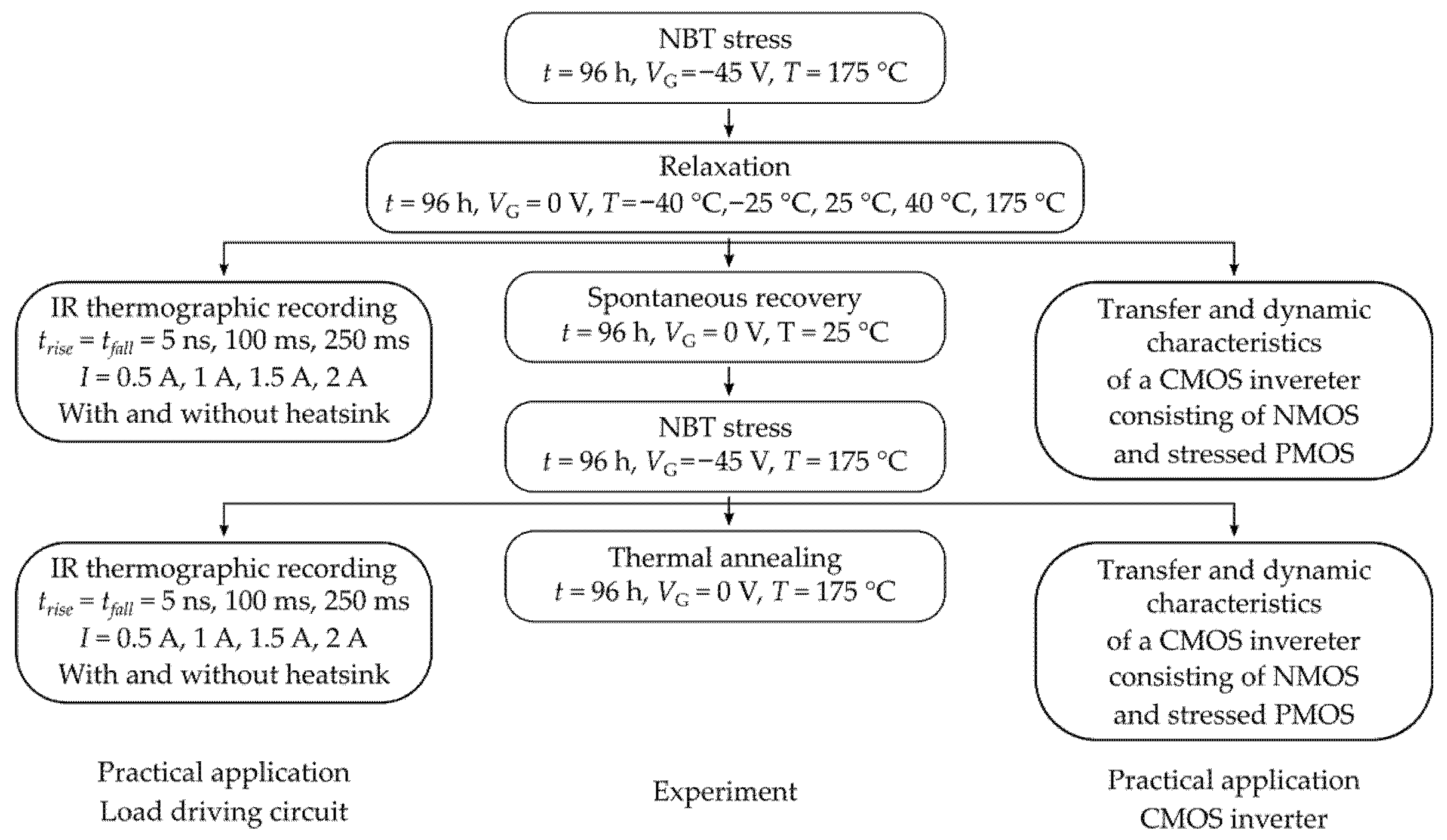

2. Experiment

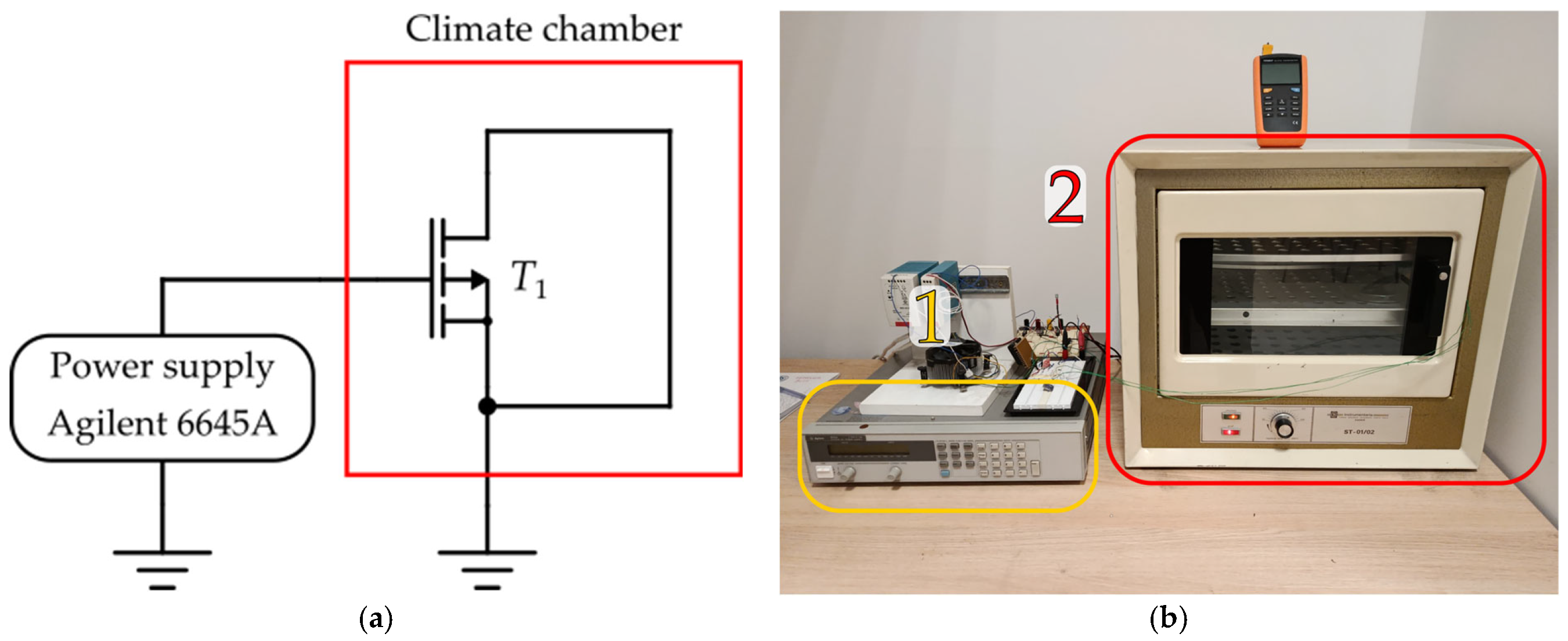

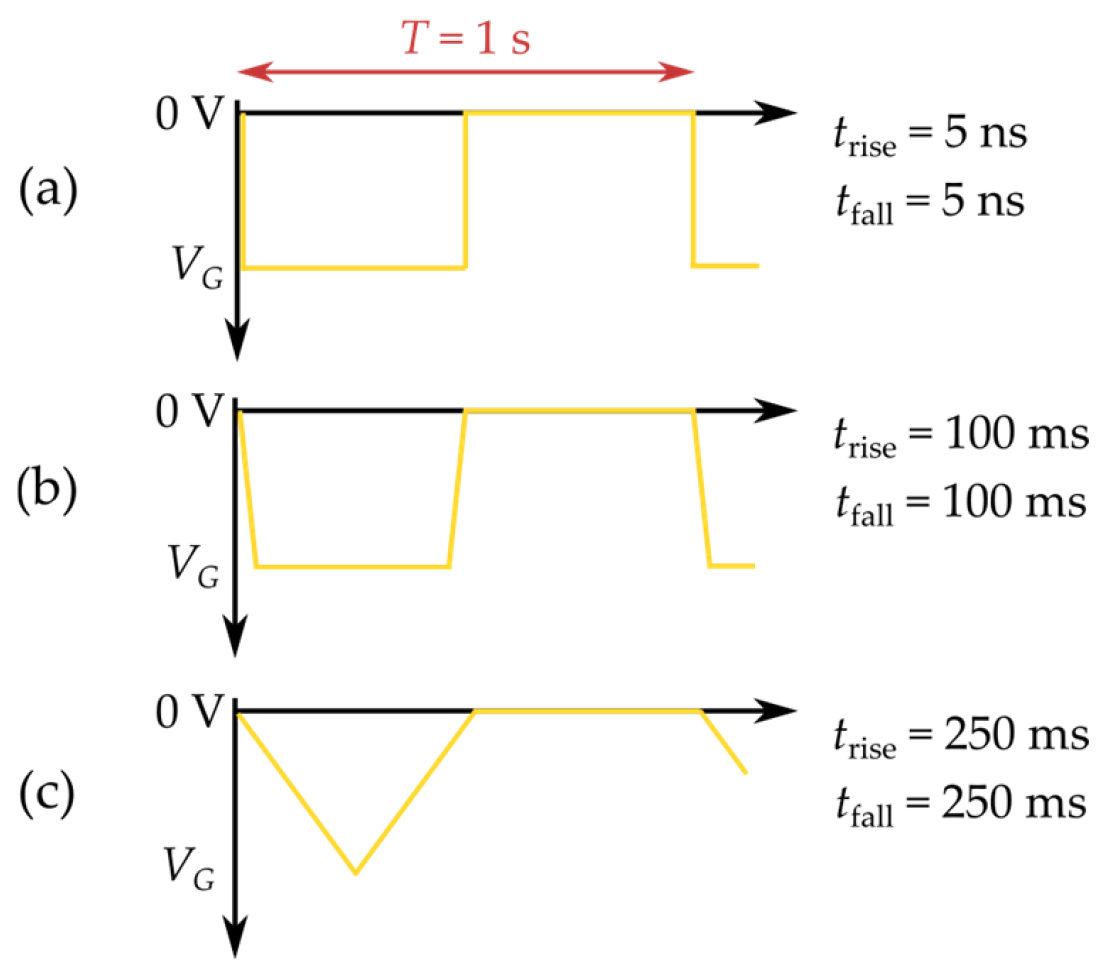

2.1. Stressing

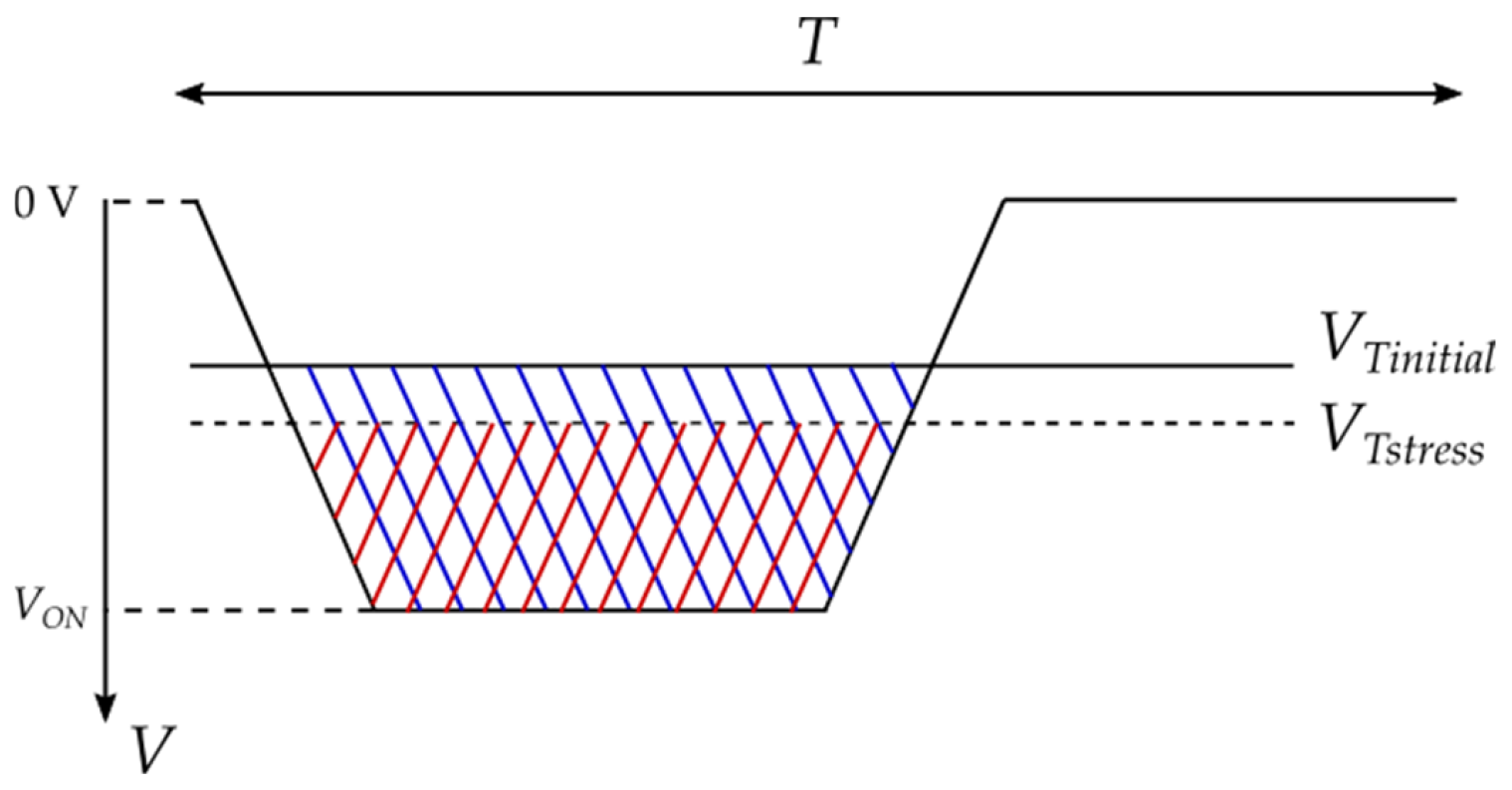

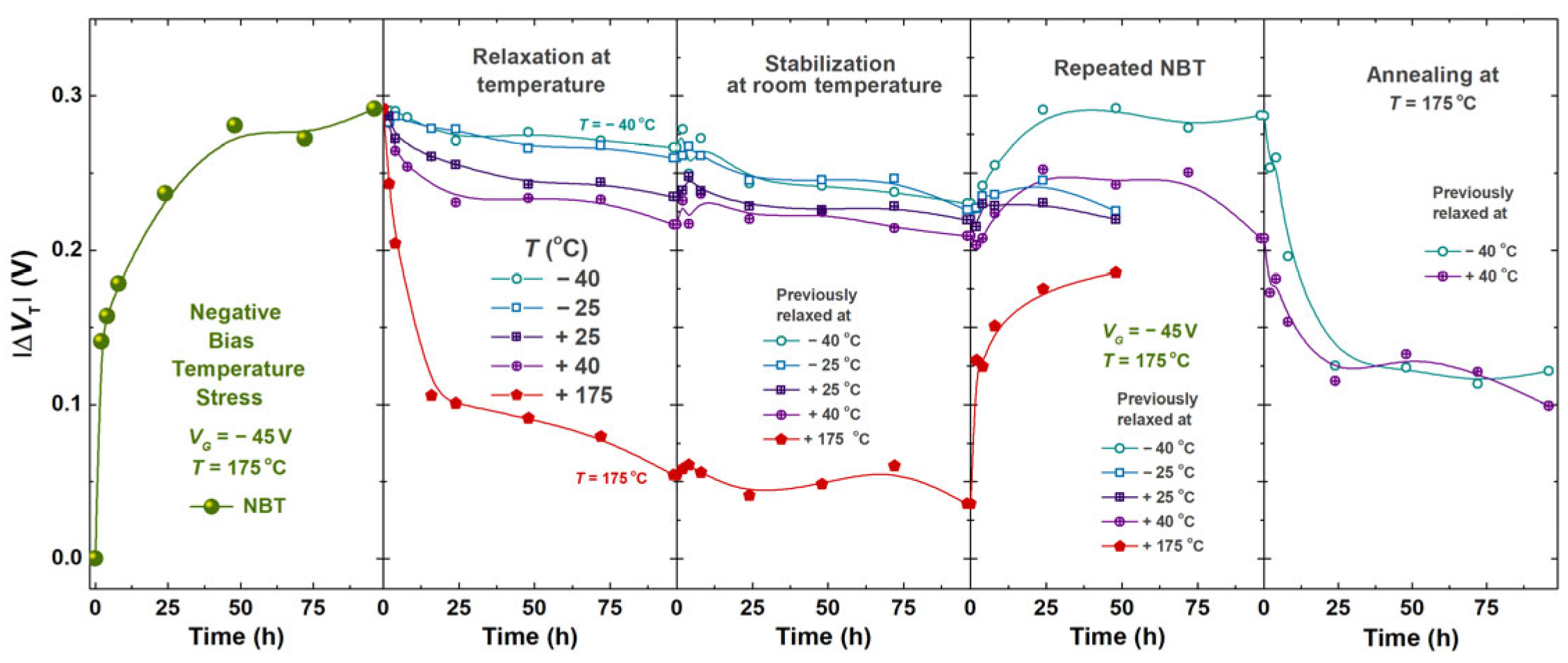

2.1.1. Negative Bias Temperature Stressing

2.1.2. Relaxation

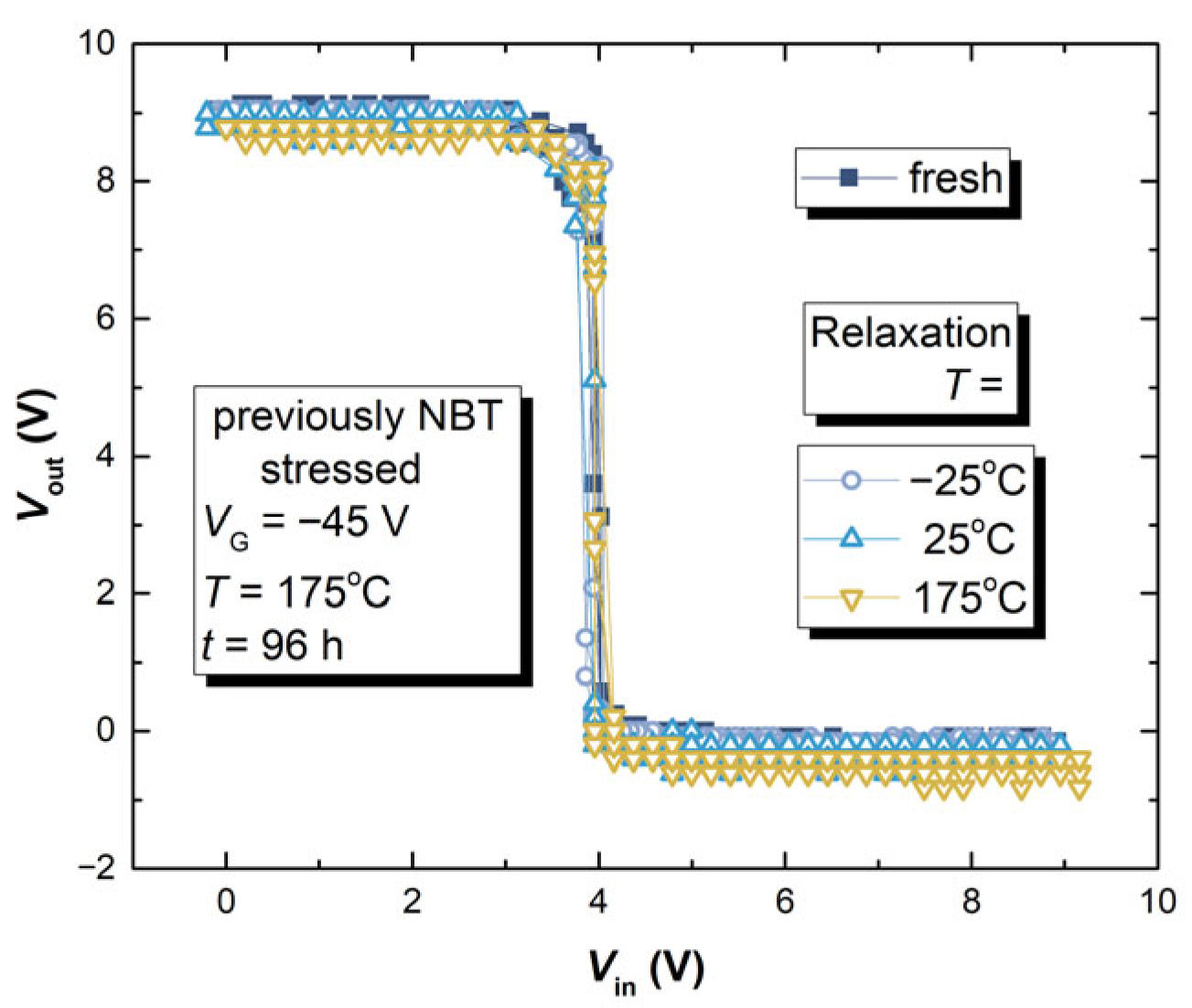

2.1.3. Continuation of the Experiment

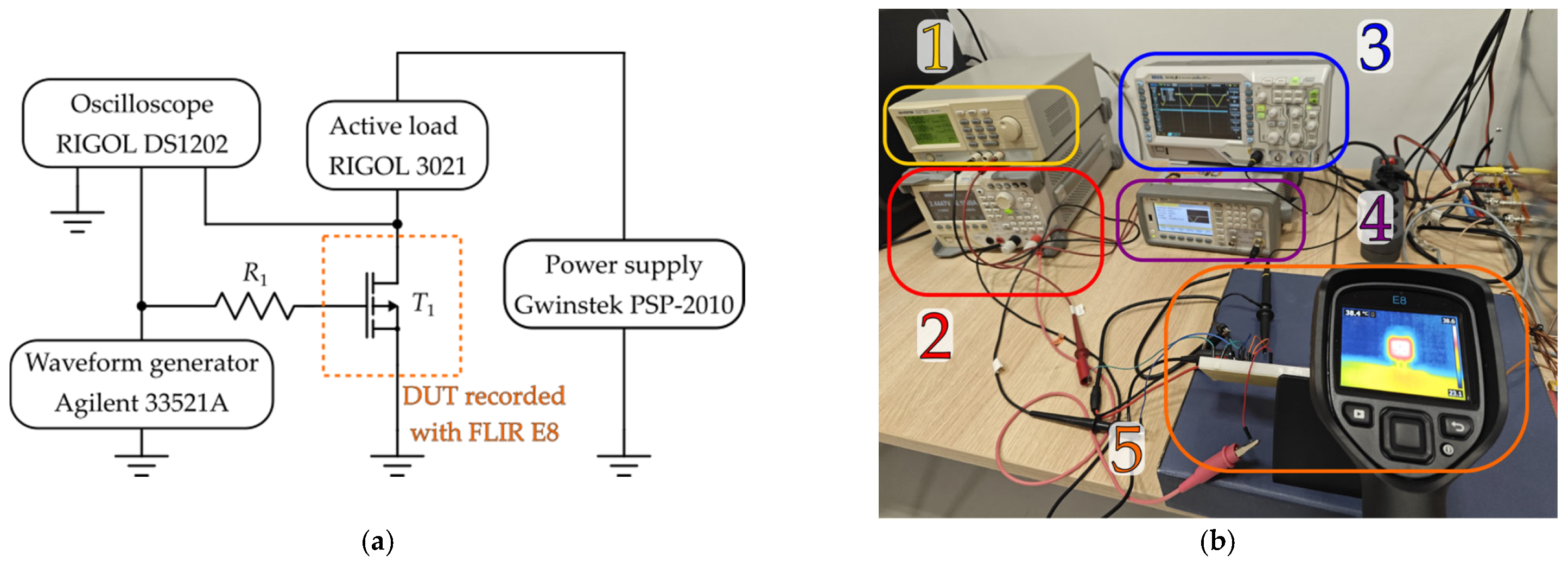

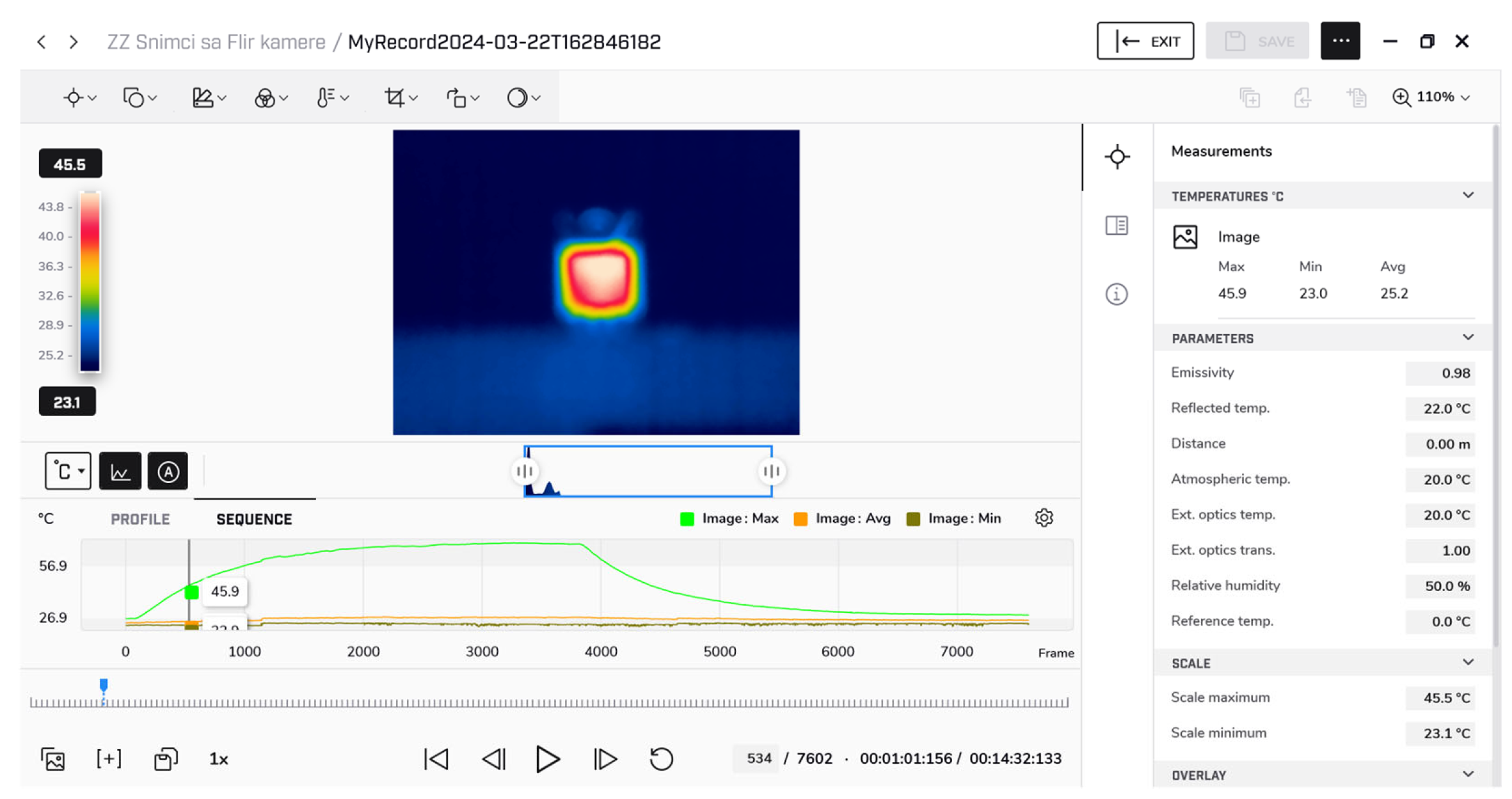

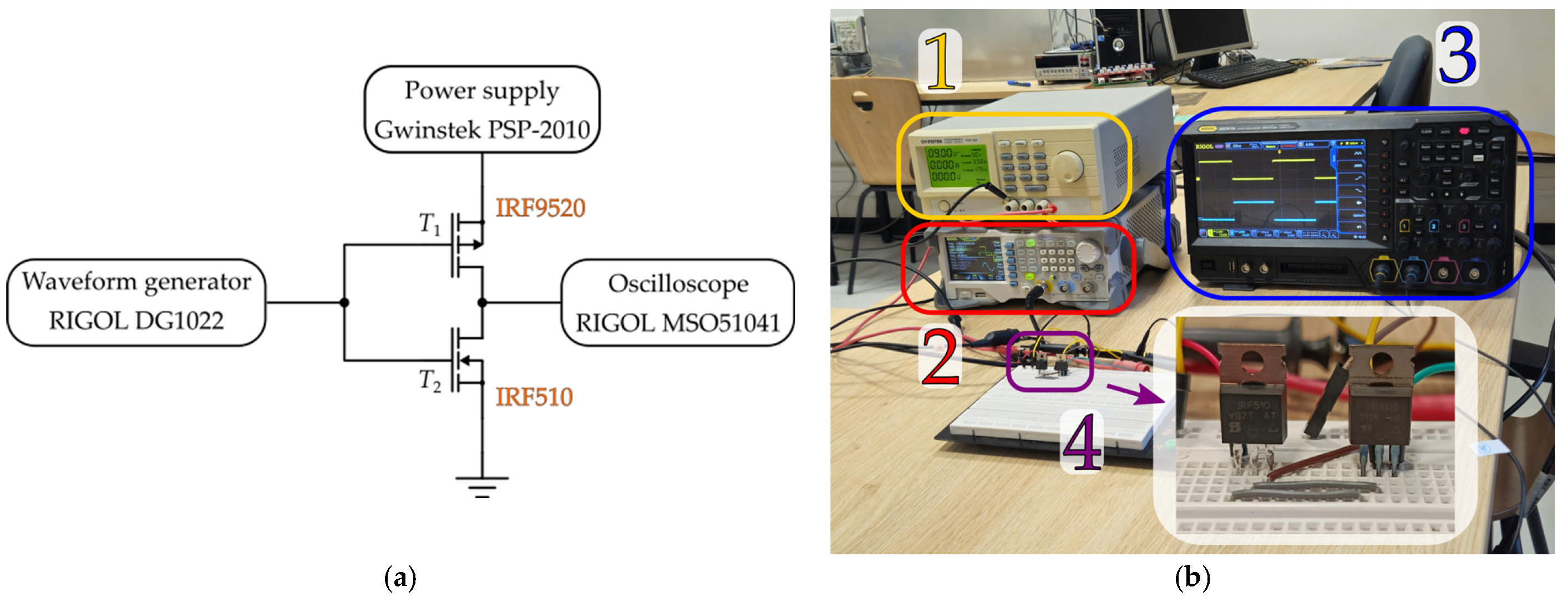

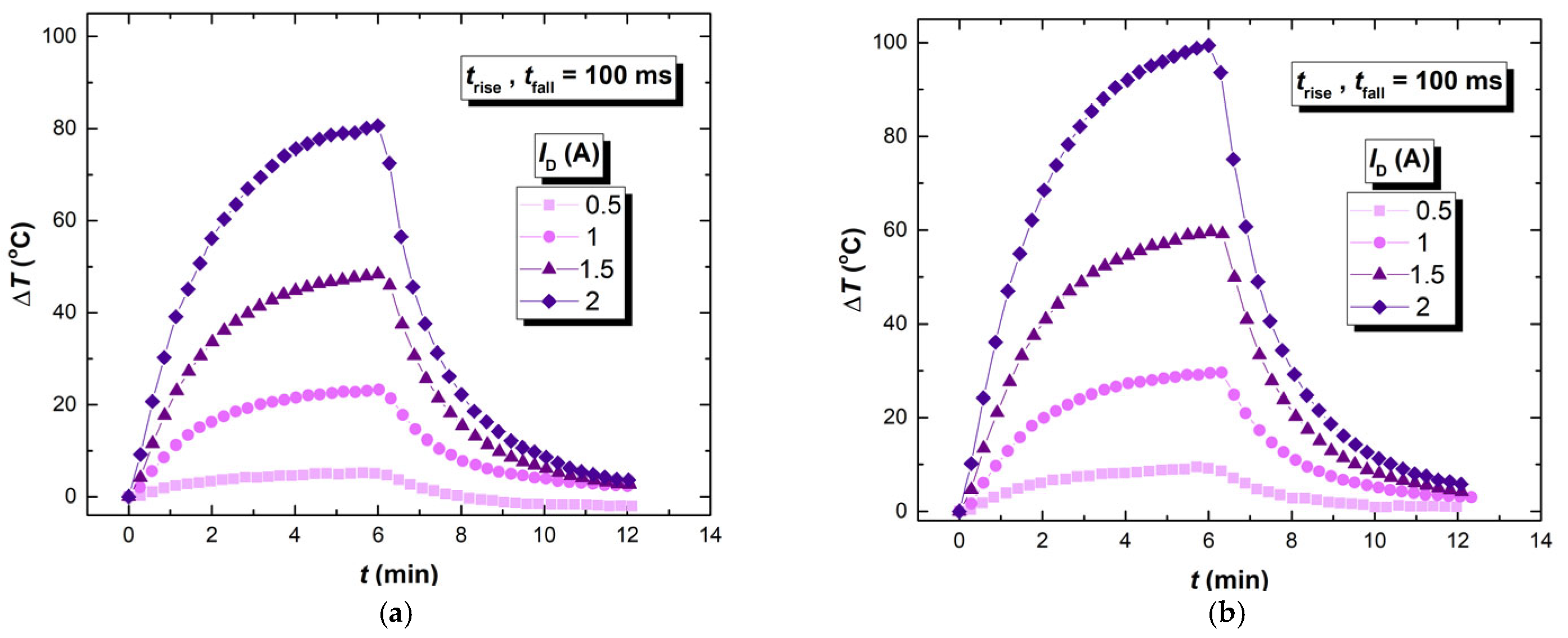

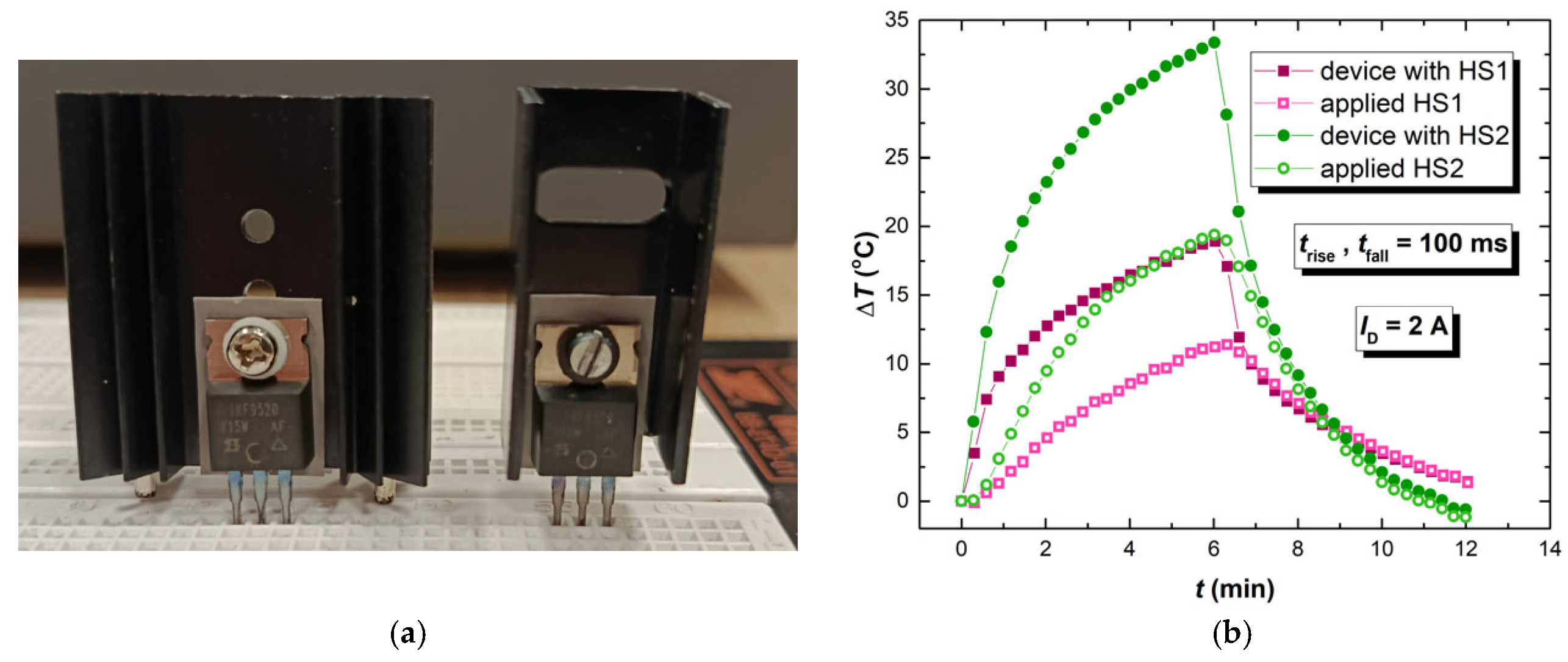

2.2. Infra-Red Thermographic Recordings

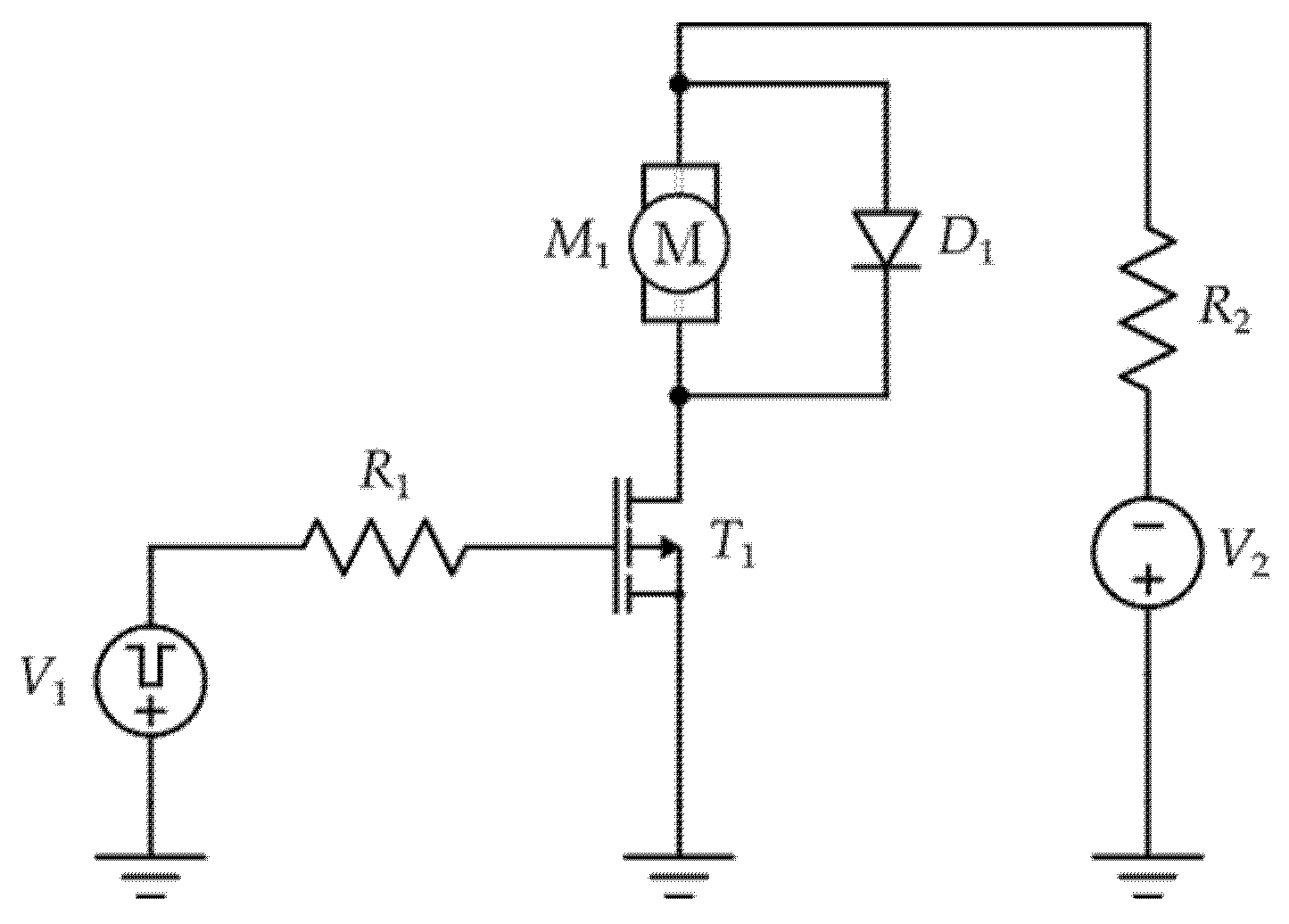

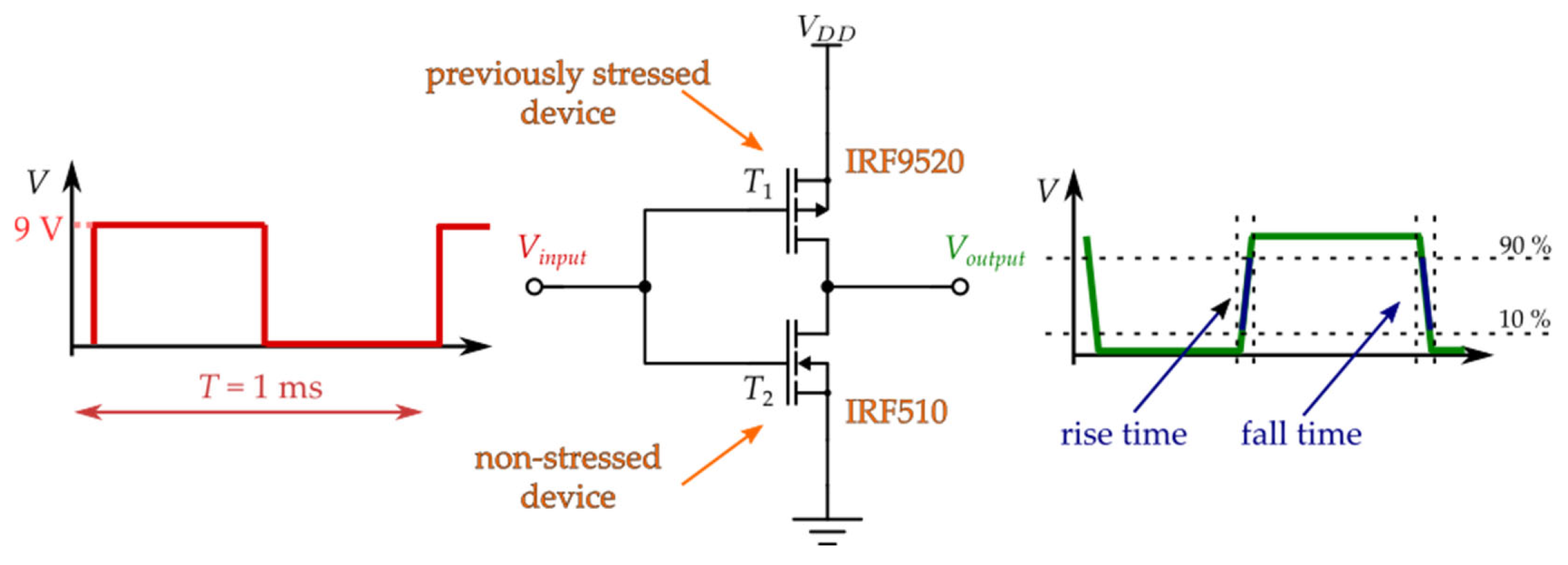

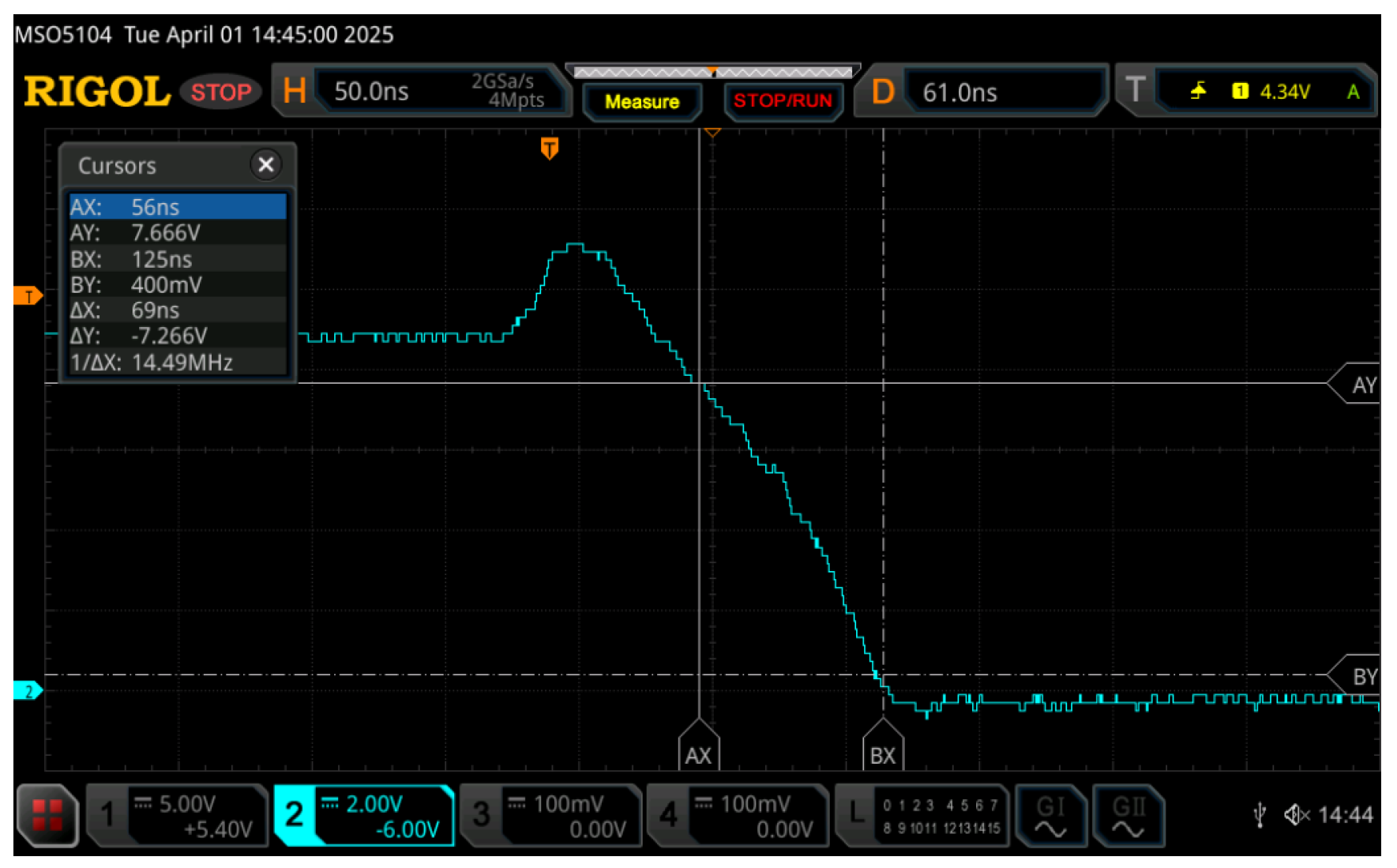

2.3. Characterization of CMOS Inverter Containing NBT Stressed Device

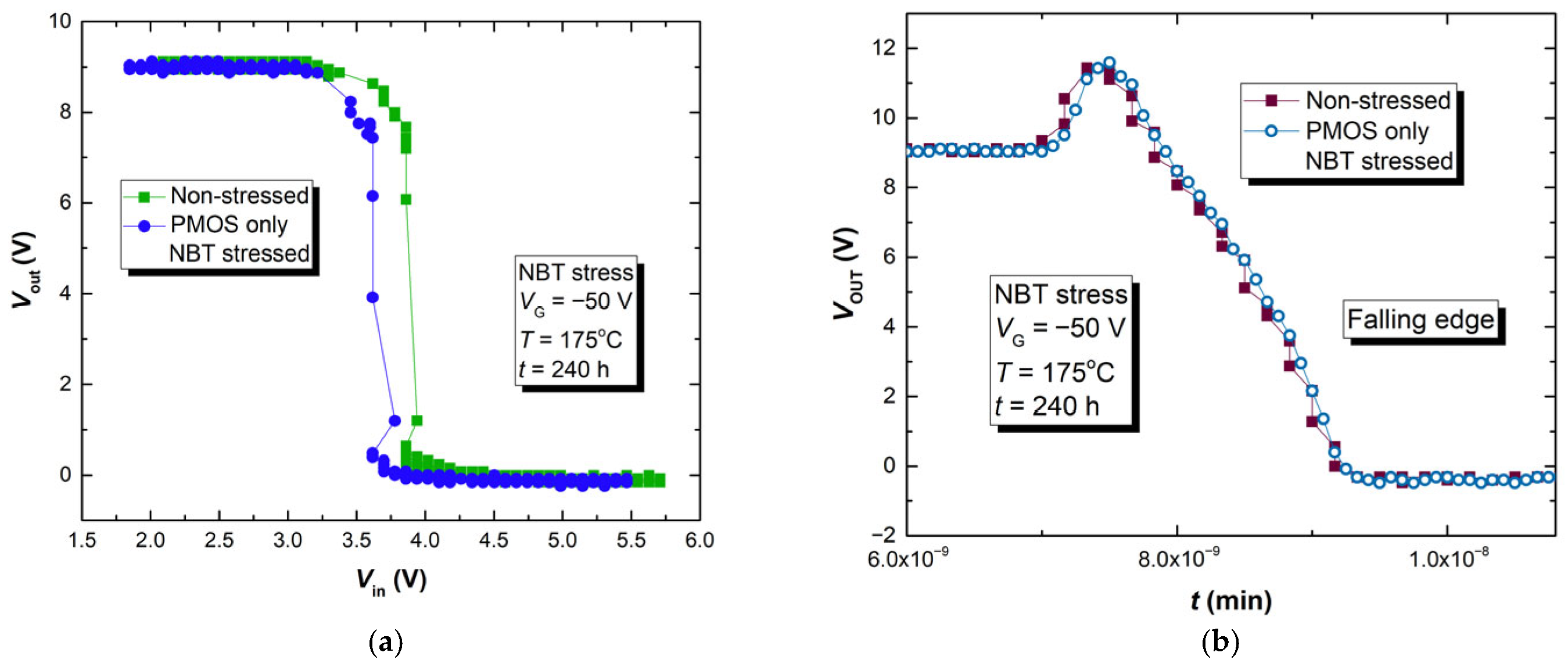

3. Results and Discussion

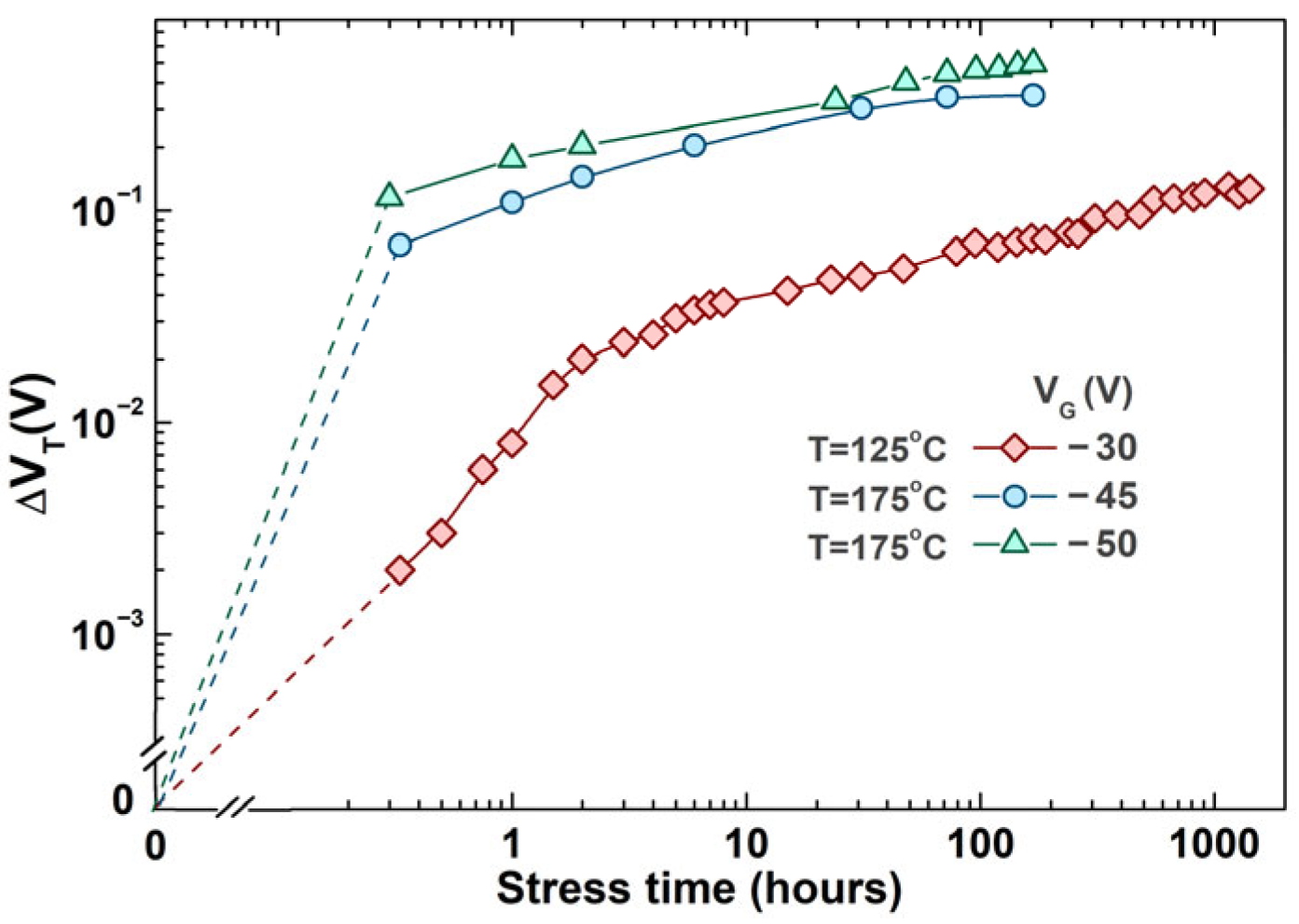

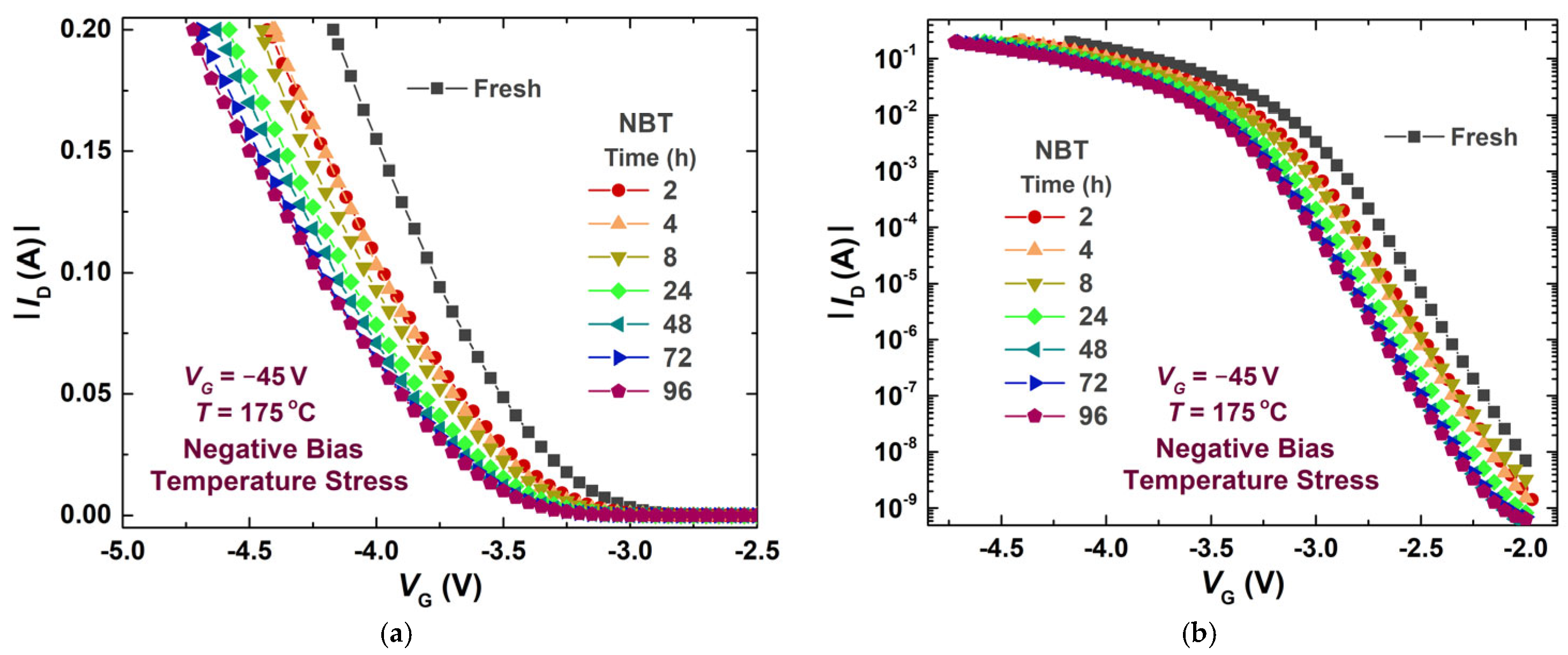

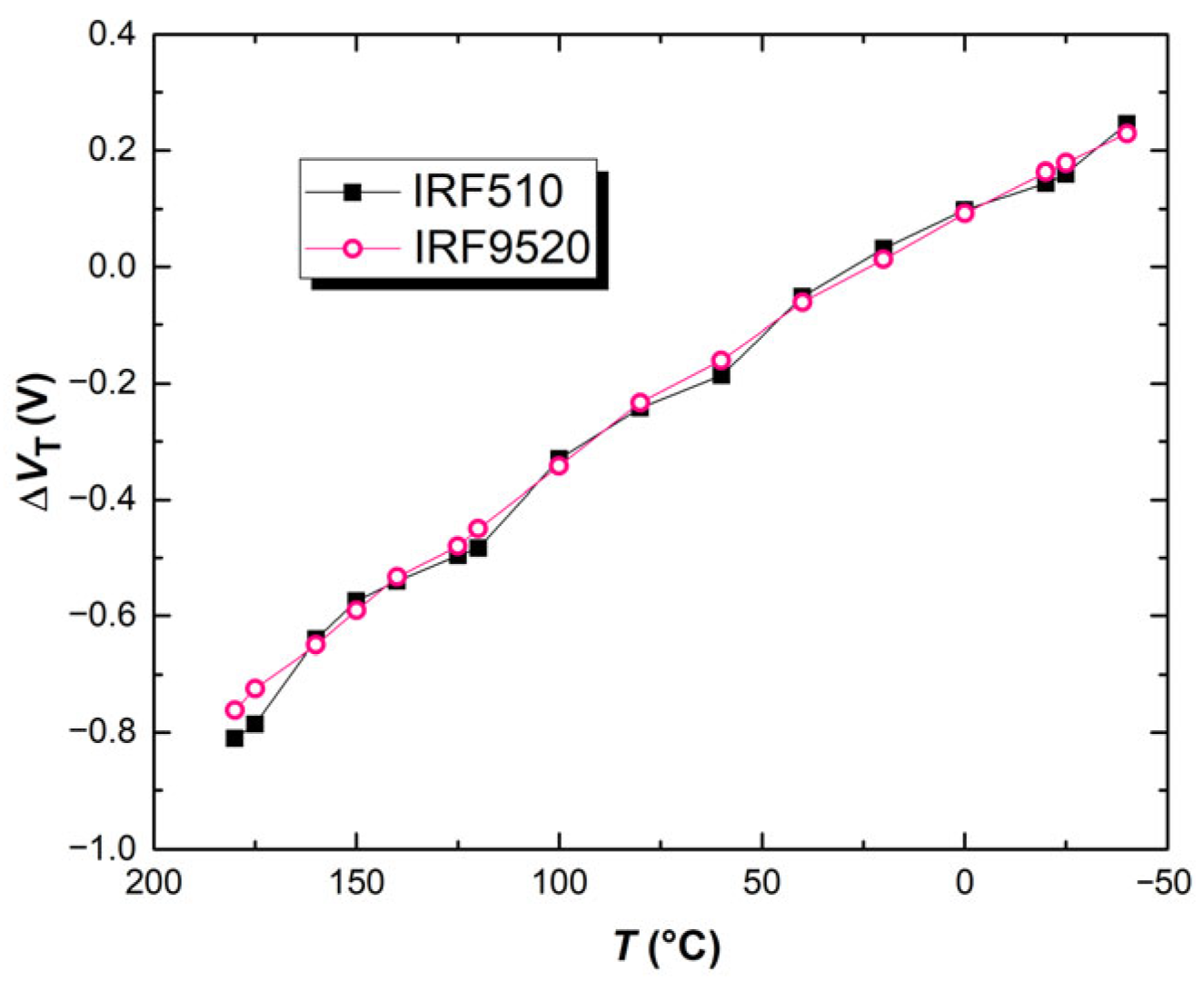

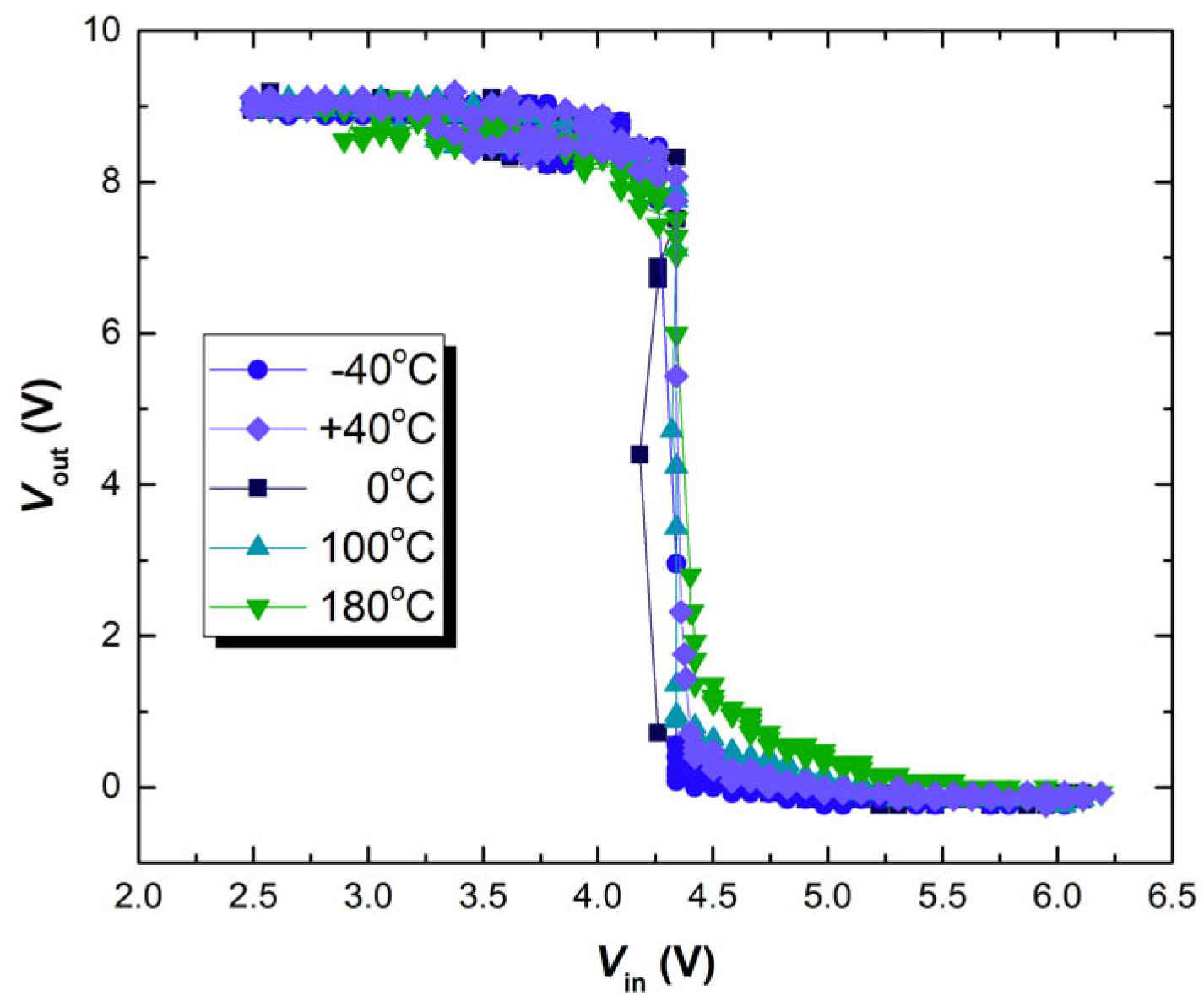

3.1. Stress-Induced Threshold Voltage Shift

3.2. Self-Heating in Practical Applications

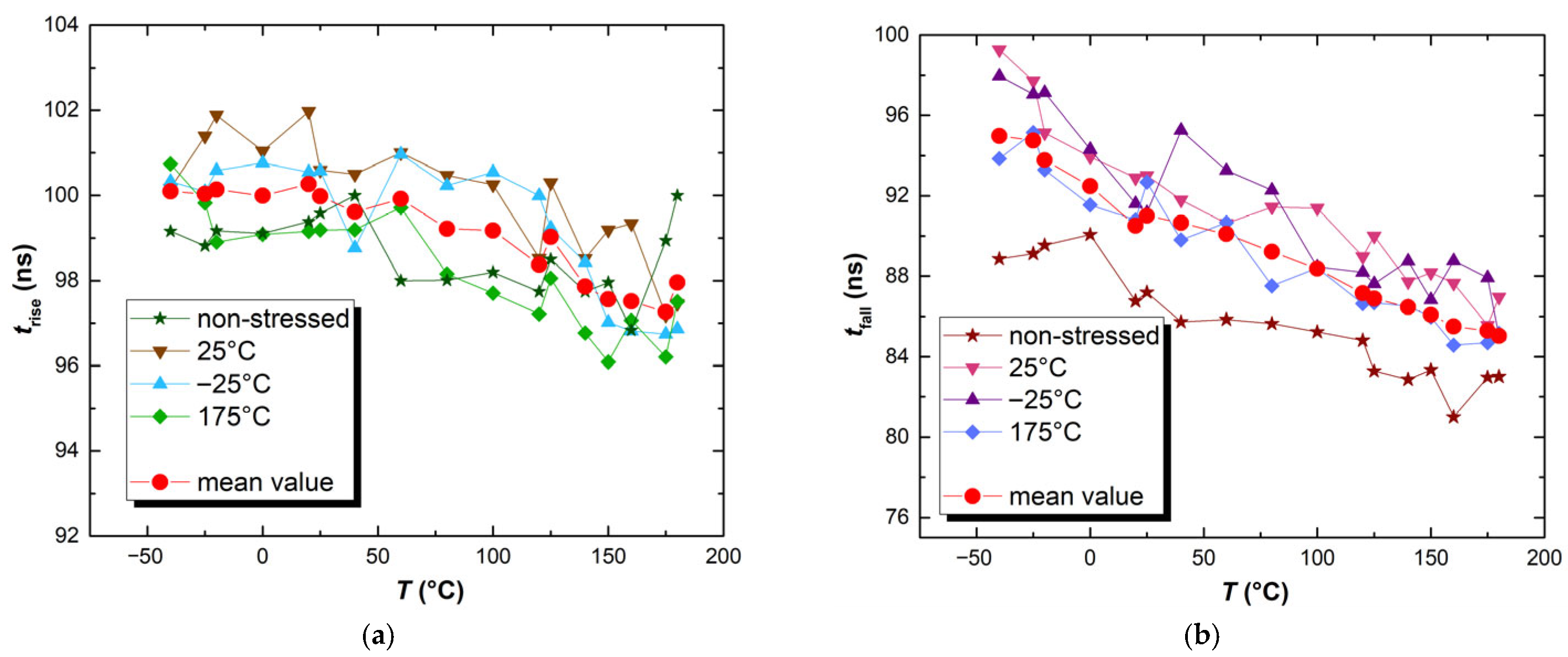

3.3. Impact of Stressing on the CMOS Inverter Circuit Performance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chee, K.W.A.; Ye, T. In Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor; Yeap, K.H., Nisar, H., Eds.; Towards New Generation Power MOSFETs for Automotive Electric Control Units. InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Kalra, S.; Mahur, J. Evaluating NBTI and HCI effects on device reliability for high-performance applications in advanced CMOS technologies. FU Electron. Energetics 2024, 37, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Das, A.; Sahu, D.K.; Pradhan, S.N.; Das, K. A Meta-Heuristic Search-Based Input Vector Control Approach to Co-Optimize NBTI Effect, PBTI Effect, and Leakage Power Simultaneously. Microelectron. Reliab. 2023, 144, 114979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Gao, R.; Duan, M.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, W.; Marsland, J. Bias Temperature Instability of MOSFETs: Physical Processes, Models, and Prediction. Electronics 2022, 11, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živanović, E.; Veljković, S.; Mitrović, N.; Jovanović, I.; Djorić-Veljković, S.; Paskaleva, A.; Spassov, D.; Danković, D. A Reliability Investigation of VDMOS Transistors: Performance and Degradation Caused by Bias Temperature Stress. Micromachines 2024, 15, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, R.; Wang, R. The Understanding and Compact Modeling of Reliability in Modern Metal–Oxide–Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors: From Single-Mode to Mixed-Mode Mechanisms. Micromachines 2024, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Pradhan, S.N. NBTI-Aware Power Gating Design with Dynamically Varying Stress Probability Control on Sleep Transistor. J. Circ. Syst. Comput. 2021, 30, 2120004. [Google Scholar]

- Grasser, T. Bias Temperature Instability for Devices and Circuits; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Kuang, F.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, C. Interaction of Negative Bias Instability and Self-Heating Effect on Threshold Voltage and SRAM (Static Random-Access Memory) Stability of Nanosheet Field-Effect Transistors. Micromachines 2024, 15, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, D.K.; Babcock, J.A. Negative bias temperature instability: Road to cross in deep submicron silicon semiconductor manufacturing. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 94, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathis, J.H.; Mahapatra, S.; Grasser, T. Controversial issues in negative bias temperature instability. Microelectron. Reliab. 2018, 81, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppson, K.O.; Svensson, C.M. Negative bias stress of MOS devices at high electric fields and degradation of MNOS devices. J. Appl. Phys. 1977, 48, 2004–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.R. VDMOSFET HEF Degradation Modelling Considering Turn-Around Phenomenon. Microelectron. Reliab. 2018, 80, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otomański, P.; Pawłowski, E.; Szlachta, A. In Situ Evaluation of the Self-Heating Effect in Resistance Temperature Sensors. Sensors 2025, 25, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broche, A.; Cerdeira, A.; Iñiguez, B.; Estrada, M. Determining the Characteristics of the Localized Density of States Distribution Present in MoS2 2D FETs. FU Electron. Energetics 2024, 37, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljković, S.; Mitrović, N.; Davidović, V.; Živanović, E.; Ristić, G.; Danković, D. Successive irradiation and bias temperature stress induced effects on commercial p-channel power VDMOS transistors. FU Electron. Energetics 2024, 37, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.; Veselinović, N.; Tasić, L.; Đorđević, D.; Veljković, S.; Mitrović, N.; Marjanović, M.; Živanović, E.; Danković, D. Investigation of NBTI and Relaxation Effects in P-Channel Power VDMOS transistors. In Proceedings of the IEEE 34th International Conference on Microelectron (MIEL), Niš, Serbia, 13–16 October 2025; pp. 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann, P.; Lichtenwalner, D.J.; Stein, S.; Park, J.-H.; Das, S.; Ryu, S.-H. Measurement of the Dit Changes Under BTI-Stress in 4H-SiC FETs Using the Subthreshold Slope Method. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), Grapevine, TX, USA, 14–18 April 2024; p. P58.SiC. [Google Scholar]

- Danković, D.; Manić, I.; Prijić, A.; Davidović, V.; Prijić, Z.; Golubović, S.; Djorić-Veljković, S.; Paskaleva, A.; Spassov, D.; Stojadinović, N. A review of pulsed NBTI in P-channel power VDMOSFETs. Microelectron. Reliab. 2018, 82, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volosov, V.; Bevilacqua, S.; Anoldo, L.; Tosto, G.; Fontana, E.; Russo, A.-L.; Fiegna, C.; Sangiorgi, E.; Tallarico, A.N. Positive Bias Temperature Instability in SiC-Based Power MOSFETs. Micromachines 2024, 15, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, T.; Dhyani, M.; Bernstein, J. Reliability Challenges, Models, and Physics of Silicon Carbide and Gallium Nitride Power Devices. Energies 2025, 18, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Rectifier. IRF9520 Datasheet; International Rectifier: El Segundo, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vishay. P-Channel MOSFETs, the Best Choice for High-Side Switching; Technical Report AN804; Vishay: Malvern, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moens, P.; Cano, J.F.; De Keukeleire, C.; Desoete, B.; Aresu, S.; De Ceuninck, W.; De Vleeschouwer, H.; Tack, M. Self-Heating Driven VthShifts in Integrated VDMOS Transistors. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices & IC’s, Naples, Italy, 4–8 June 2006; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Aviñó-Salvadó, O.; Buttay, C.; Bonet, F.; Raynaud, C.; Bevilacqua, P.; Rebollo, J.; Morel, H.; Perpiñà, X. Physics-Based Strategies for Fast TDDB Testing and Lifetime Estimation in SiC Power MOSFETs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 71, 5285–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, D.; Tasić, L.; Veselinović, N.; Petrović, M.; Veljković, S.; Mitrović, N.; Marjanović, M.; Živanović, E.; Ristić, G.; Danković, D. Investigation of the Self-Heating Effect in P-Channel VDMOS Transistor after NBT Stress and Relaxation. In Proceedings of the IEEE 34th International Conference on Microelectron (MIEL), Niš, Serbia, 13–16 October 2025; pp. 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Hernando, F.; San-Sebastian, J.; Garcia-Bediaga, A.; Arias, M.; Iannuzzo, F.; Blaabjerg, F. Wear-Out Condition Monitoring of IGBT and MOSFET Power Modules in Inverter Operation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 6184–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenouf, A.; Djezzar, B.; Benadelmoumene, A.; Tahi, H. Deep experimental investigation of NBTI impact on CMOS inverter reliability. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Microelectronics (ICM), Doha, Qatar, 14–17 December 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Yepes, A.; Nasarre, C.; Garsot, N.; Martin-Martinez, J.; Rodriguez, R.; Barajas, E.; Aragones, X.; Mateo, D.; Nafria, M. CMOS inverter performance degradation and its correlation with BTI, HCI and OFF state MOSFETs aging. Solid-State Electron. 2022, 191, 108264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbel, N.; Fernandez, R.; Gil, I. Modelling and experimental verification of the impact of negative bias temperature instability on CMOS inverter. Microelectron. Reliab. 2009, 49, 1048–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unutulmaz, A.; Helms, D.; Eilers, R.; Metzdorf, M.; Kaczer, B.; Nebel, W. Analysis of NBTI Effects on High Frequency Digital Circuits. In Proceedings of the 2016 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Dresden, Germany, 14–18 March 2016; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Veselinović, N.; Petrović, M.; Đorđević, D.; Tasić, L.; Mitrović, N.; Veljković, S.; Marjanović, M.; Živanović, E.; Davidović, V.; Danković, D. Impact of NBTS and Thermal Relaxation on Characteristics of CMOS inverter. In Proceedings of the IEEE 34th International Conference on Microelectron (MIEL), Niš, Serbia, 13–16 October 2025; pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Prijić, A.; Danković, D.; Vračar, L.; Manić, I.; Prijić, Z.; Stojadinović, N. A method for negative bias temperature instability (NBTI) measurements on power VDMOS transistors. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 085003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.; Velarde Gonzalez, F.A.; Giering, K.-U.; Vervantidis, A.; Hahne, L.; Heinig, A.; Jancke, R. A General Approach for Degradation Modeling to Enable a Widespread Use of Aging Simulations in IC Design. Microelectron. Reliab. 2022, 137, 114775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Rectifier. IRF510 Datasheet; International Rectifier: El Segundo, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, V.; Andreev, D.; Andreev, V.; Piskunov, S.; Popov, A.I. The Compact Model Synthesis for the RADFET Device. Technologies 2025, 13, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gao, B.; Deng, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, D.; Wang, L.; Luo, J.; Han, Z. Failure analysis of the VDMOS device with Vsd and Rds (on) exceeded limit based on reliability physics. In Proceedings of the Prognostics and System Health Management Conference (PHM-Chengdu), Chengdu, China, 19–21 October 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Elektronik. Fischer Elektronik Heatsink SK 104 50.8 STIS, Datasheet; Fischer Elektronik: Ludenscheid, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alutronic. Alutronic Heatsink PR17/35II/SE, Datasheet; Alutronic: Halver, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D9 | D10 | D11 | D12 | D13 | D14 | D15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBTS, t = 96 h VG = −45 V, T = 175 °C | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Relaxation, t = 96 h T = 175 °C | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Relaxation, t = 96 h T = 40 °C | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Relaxation, t = 96 h T = 25 °C | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Relaxation, t = 96 h T = −25 °C | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Relaxation, t = 96 h T = −40 °C | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| IR and CMOS | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Spont. Recovery, t = 96 h, T = 25 °C | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| NBTS, t = 96 h VG = −45 V, T = 175 °C | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| IR and CMOS | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Annealing, t = 96 h T = 175 °C | X | X | X | X | X |

| Drain Current [A] | Initial Rates (First 60 s) [°C/min] | Average Rates [°C/min] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heating | Cooling | Heating | Cooling | |

| 0.5 | 2.42 | 3.39 | 0.87 | 0.52 |

| 1 A | 11.2 | 10.92 | 3.88 | 3.50 |

| 1.5 A | 23.00 | 22.77 | 8.06 | 7.62 |

| 2 A | 39.12 | 43.04 | 13.43 | 12.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Danković, D.; Živanović, E.; Veselinović, N.; Đorđević, D.; Petrović, M.; Tasić, L.; Marjanović, M.; Veljković, S.; Mitrović, N.; Davidović, V.; et al. Examination of Impact of NBTIs on Commercial Power P-Channel VDMOS Transistors in Practical Applications. Micromachines 2026, 17, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010052

Danković D, Živanović E, Veselinović N, Đorđević D, Petrović M, Tasić L, Marjanović M, Veljković S, Mitrović N, Davidović V, et al. Examination of Impact of NBTIs on Commercial Power P-Channel VDMOS Transistors in Practical Applications. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleDanković, Danijel, Emilija Živanović, Nevena Veselinović, Dunja Đorđević, Marija Petrović, Lana Tasić, Miloš Marjanović, Sandra Veljković, Nikola Mitrović, Vojkan Davidović, and et al. 2026. "Examination of Impact of NBTIs on Commercial Power P-Channel VDMOS Transistors in Practical Applications" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010052

APA StyleDanković, D., Živanović, E., Veselinović, N., Đorđević, D., Petrović, M., Tasić, L., Marjanović, M., Veljković, S., Mitrović, N., Davidović, V., & Ristić, G. (2026). Examination of Impact of NBTIs on Commercial Power P-Channel VDMOS Transistors in Practical Applications. Micromachines, 17(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010052