Experimental Investigation on Cutting Force and Hole Quality in Milling of Ti-6Al-4V

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup

2.1. Workpiece Material and Cutting Tool

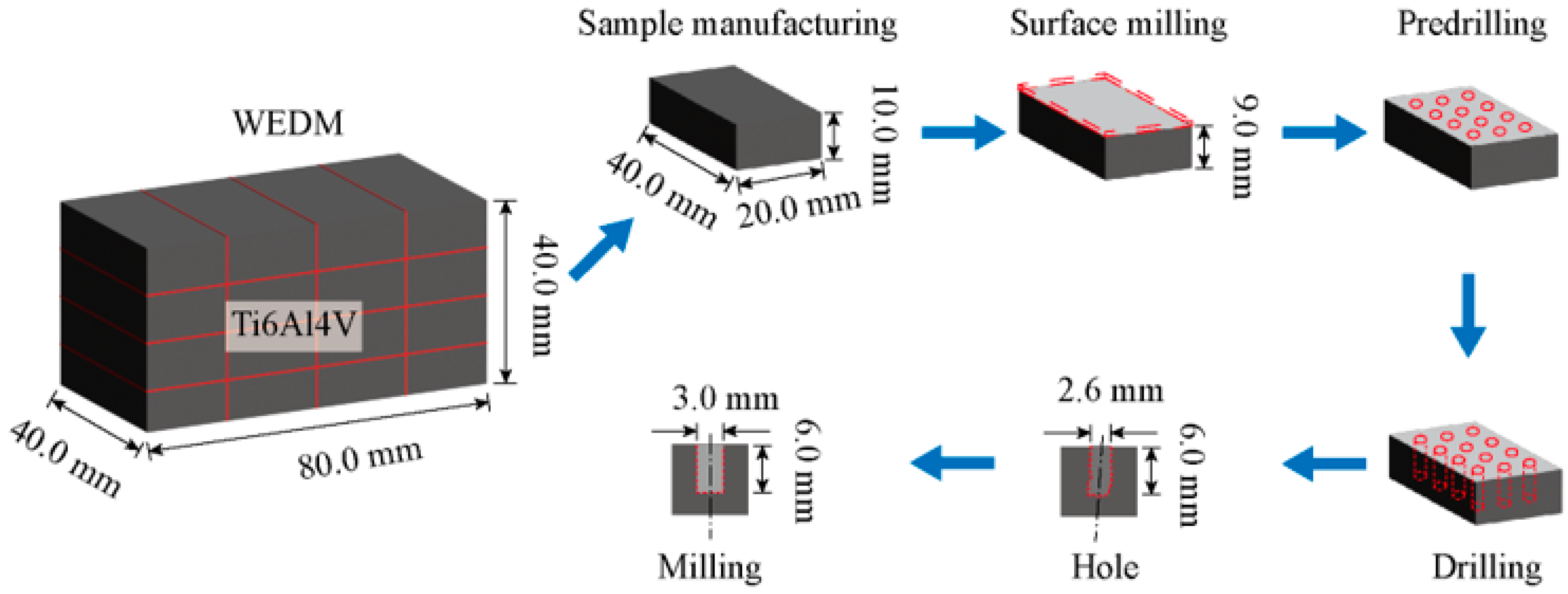

2.2. Milling Experimental Procedure

2.3. Milling Machining Mechanism

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Milling Parameters on Milling Force and Parameter Optimization

3.2. Effect of Milling Parameters on Burr Formation

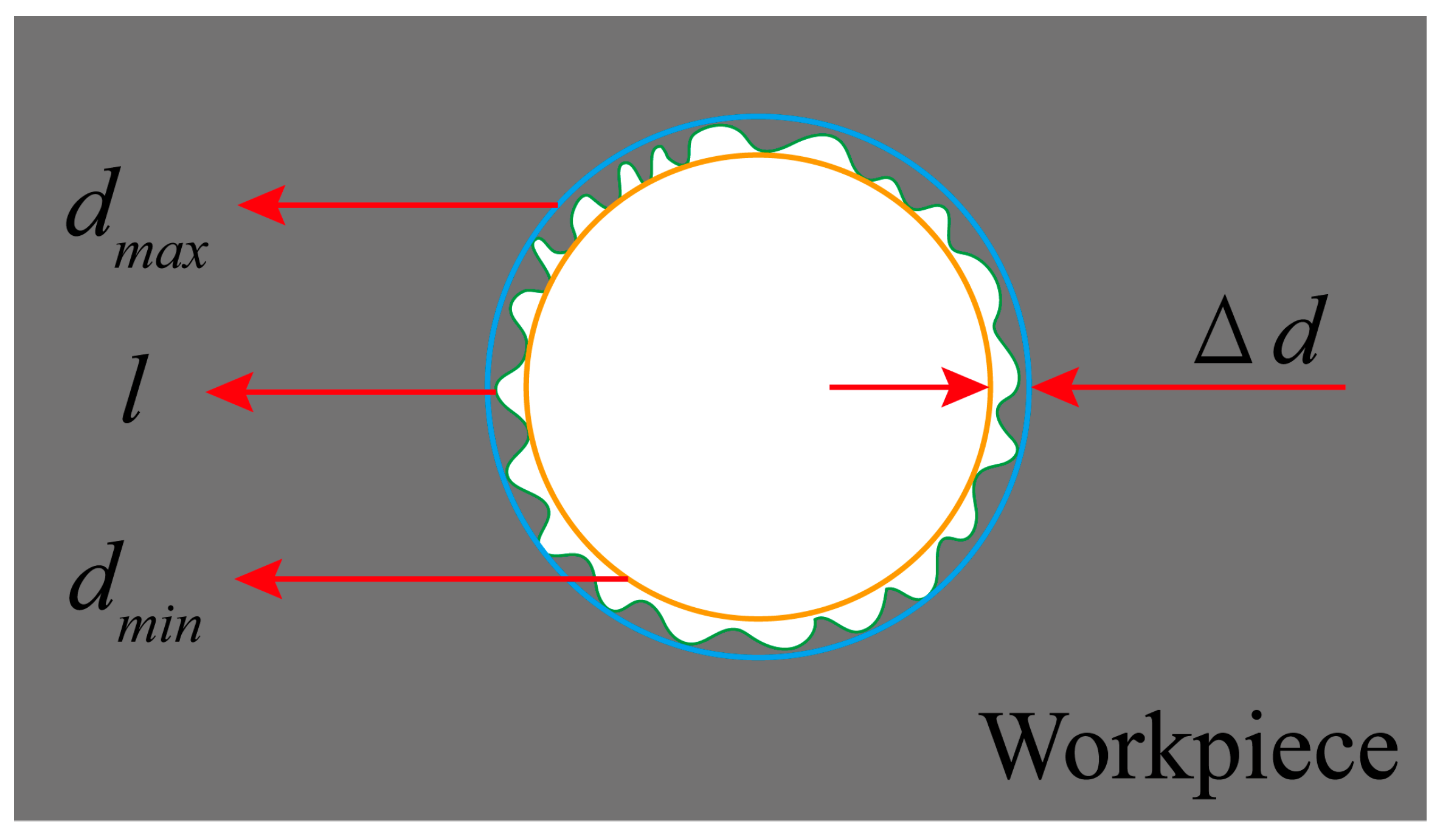

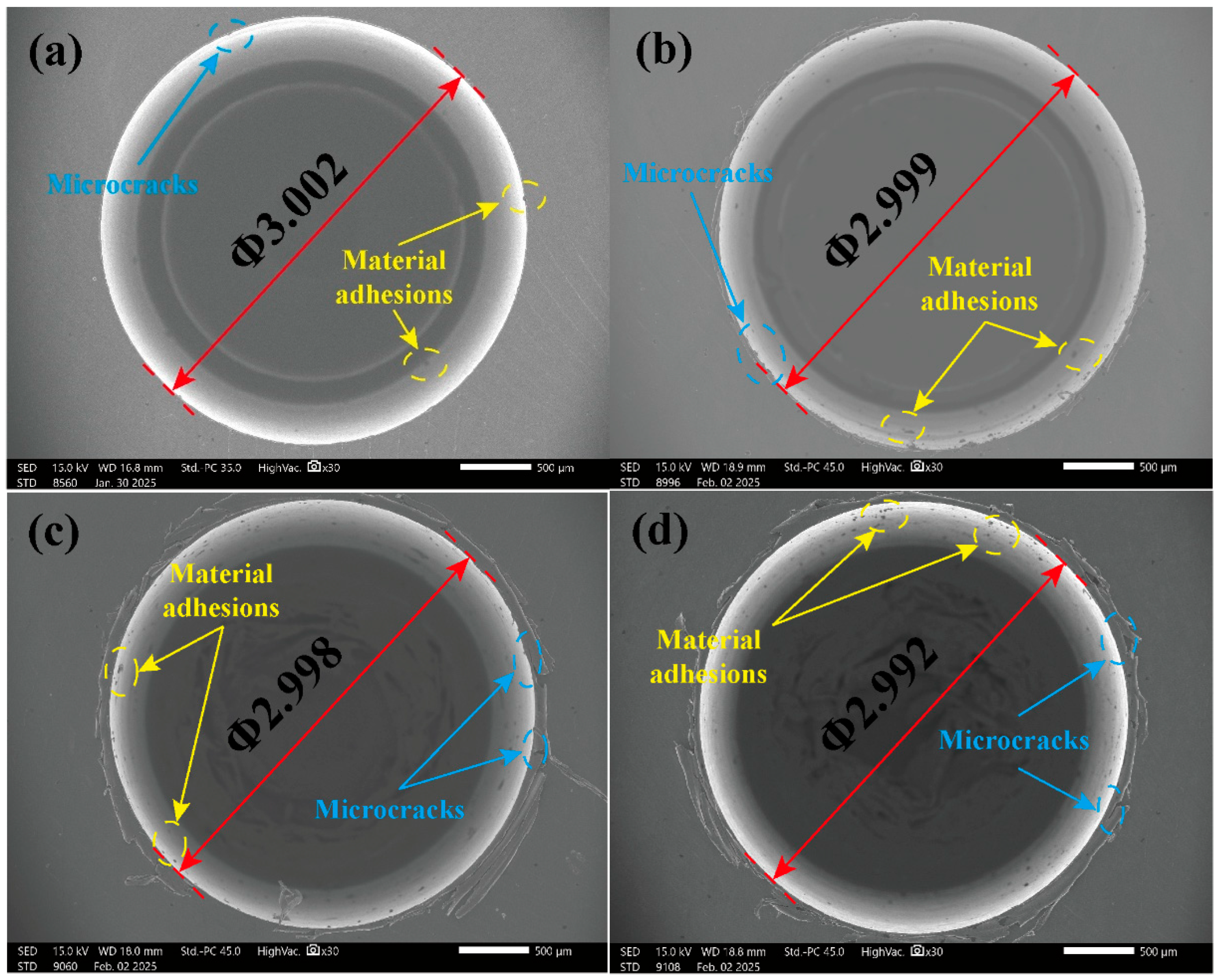

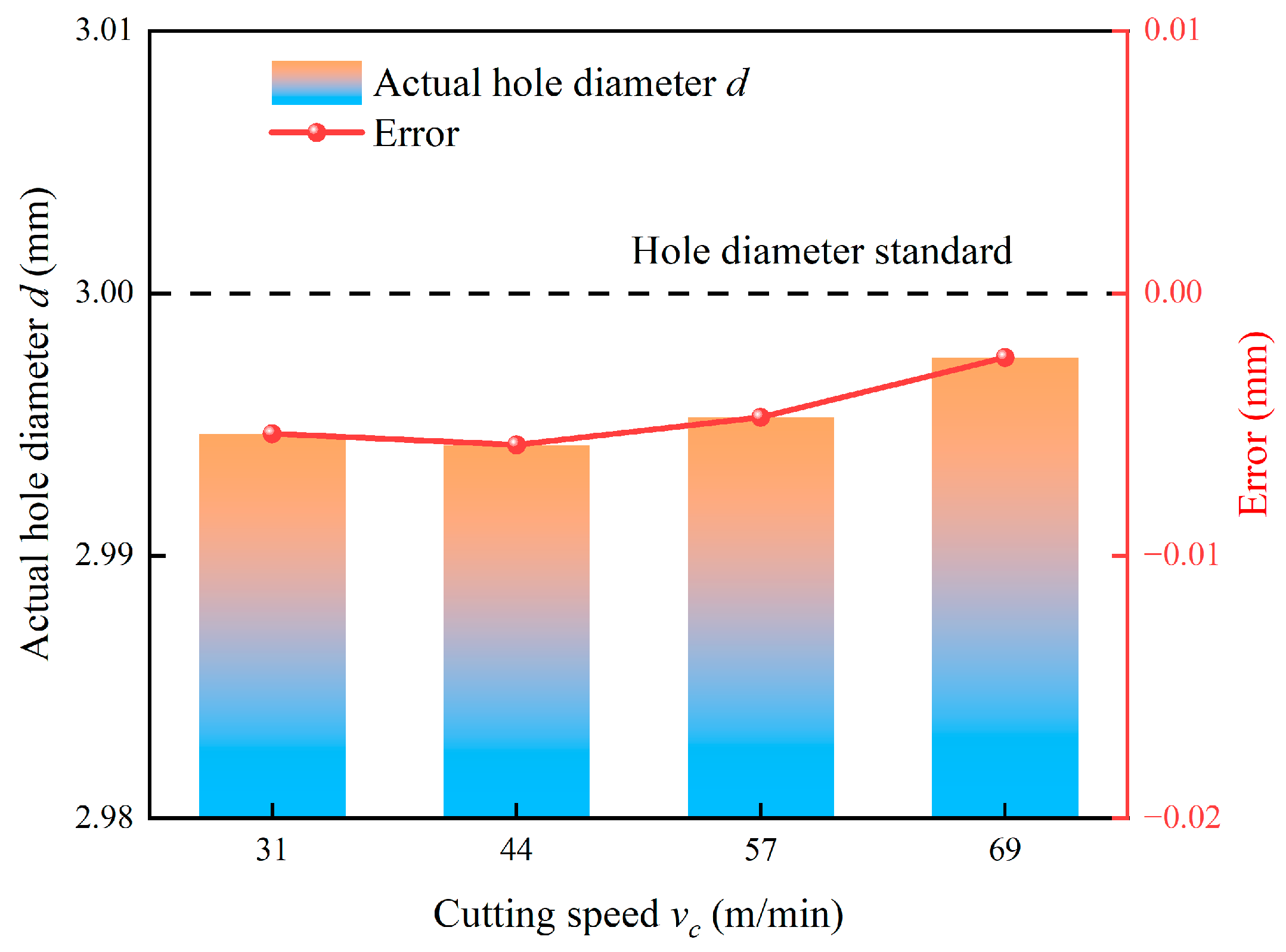

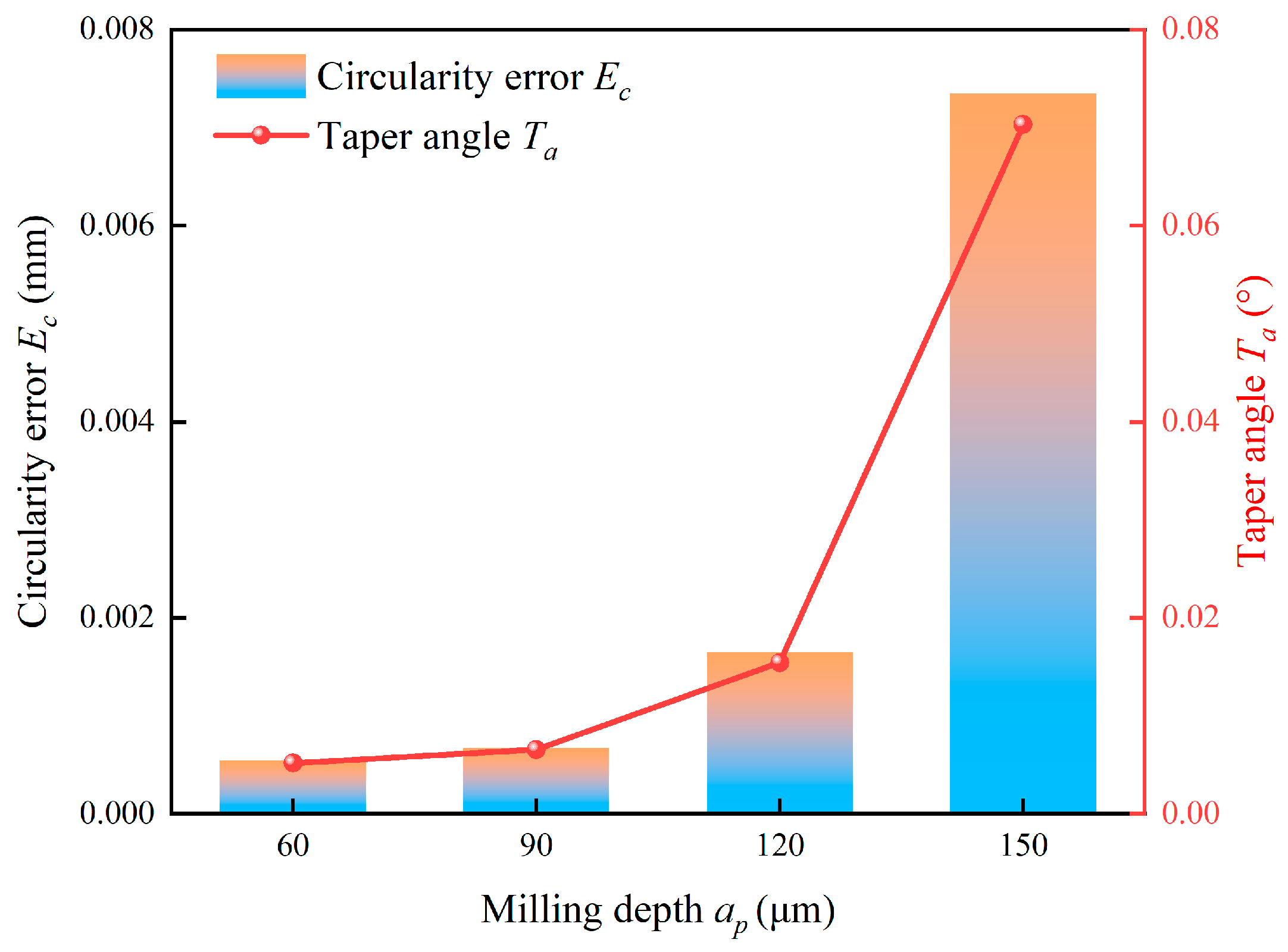

3.3. Effect of Milling Parameters on Hole Geometrical Accuracy

4. Conclusions

- Milling force is predominantly governed by the milling depth, which exhibits the most significant influence due to its direct proportionality to the uncut chip cross-sectional area and the resultant tool deflection. Feed per tooth is the secondary factor, while cutting speed demonstrates a non-monotonic influence, where a transition from strain-rate hardening to thermal softening dominance leads to a force reduction at elevated speeds. The optimal parameter combination for minimizing the resultant force to 3.61 N was identified as a milling depth of 60 μm, a feed per tooth of 2 μm/z and a cutting speed of 31 m/min.

- Burr formation at the hole entrance is critically dependent on the interplay between material plastic flow and the cutting mechanism. Burr width increases with feed per tooth due to the increased volume of plastically flowing material. Conversely, both milling depth and cutting speed exhibit nonlinear relationships with burr size, governed by competing mechanisms. Increasing depth intensifies plastic flow, yet excessive depth may induce fracture. While higher speeds initially promote strain rate hardening, they ultimately suppress burring formation through thermal softening effects and improved material shearing.

- The geometrical accuracy of holes is primarily determined by the dynamic stability of the machining system, which is heavily influenced by tool deflection and chatter. Larger milling depth and feed per tooth exacerbate tool deflection, leading to undersized holes and degraded form accuracy. The relationship between cutting speed and geometrical errors is characterized by a distinct stability lobe effect. The critical speed of 44 m/min excites system resonance, which causes peak errors. However, higher rotational speeds between 57 m/min and 69 m/min stabilize the machining process and significantly enhance hole quality.

- Based on the multi-objective analysis, an optimal parameter window for balancing low cutting force, minimal burr formation, and high geometrical accuracy in milling of Ti-6Al-4V is identified: a milling depth of 60–90 μm, a feed per tooth of 2–3 μm/z, and a cutting speed of 57–69 m/min.

- The research underscores that successful process optimization for high-quality holes requires a multi-objective approach that balances the often-conflicting trends in cutting force, burr suppression and geometrical integrity. The findings provide a crucial experimental database and mechanistic understanding for selecting parameters that ensure precision and reliability in the manufacturing of high-value aerospace components.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, K.; Hodgson, P.; Birbilis, N.; Weyland, M.; Fraser, H.L.; Lim, S.C.V.; Peng, H.; et al. Ultrastrong nanotwinned titanium alloys through additive manufacturing. Nat. Mater. 2022, 21, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.; Weng, F.; Sui, S.; Chew, Y.; Bi, G. Progress and perspectives in laser additive manufacturing of key aeroengine materials. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2021, 170, 103804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debard, B.; Rey, P.A.; Cherif, M. Investigation of burr formation in Ti-6Al-4V drilling. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 142, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.K.; Dwivedi, S.; Dixit, A.R.; Pramanik, A. Engineering biocompatibility and mechanical performance via heat treatment of LPBF-fabricated Ti-6Al-4V for next-generation implants. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 152, 1250–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Imran Jaffery, S.H.; Khan, M.; Alruqi, M. Machinability analysis of Ti-6Al-4V under cryogenic condition. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 2204–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.; Huang, Q.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z. Development of an internally cooled turning tool with built-in vortex tube for sustainable Ti-6Al-4V machining. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 150, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Ling, C.; Zheng, L.; Zhong, Z.; Hong, Y. Continuum damage mechanics-based fatigue life prediction of L-PBF Ti-6Al-4V. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 273, 109233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Altintas, Y. Prediction of micro-milling forces with finite element method. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2012, 212, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Meng, F. Micromilling Simulation for the Hard-to-cut Material. Procedia Eng. 2017, 174, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, S.; Matuszak, M.; Powałka, B.; Madajewski, M.; Maruda, R.W.; Królczyk, G.M. Prediction of cutting forces during micro end milling considering chip thickness accumulation. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2019, 147, 103466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, K. Stress deformation simulation for optimizing milling thin-walled Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy parts. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2023, 18, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; He, C.; Yang, S. Thermo-mechanical coupling behaviour when milling titanium alloy with micro-textured ball-end cutters. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2020, 234, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moges, T.M.; Desai, K.A.; Rao, P.V.M. Improved Process Geometry Model with Cutter Runout and Elastic Recovery in Micro-end Milling. Procedia Manuf. 2016, 5, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslantas, K.; Hopa, H.E.; Percin, M.; Ucun, İ.; Çicek, A. Cutting performance of nano-crystalline diamond (NCD) coating in micro-milling of Ti6Al4V alloy. Precis. Eng. 2016, 45, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafeez, A.M.; Soo, S.L.; Aspinwall, D.K.; Dowson, A.; Arnold, D. The influence of burr formation and feed rate on the fatigue life of drilled titanium and aluminium alloys used in aircraft manufacture. CIRP Ann. 2018, 67, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnier, T.; Fromentin, G.; Marcon, B.; Outeiro, J.; D’Acunto, A.; Crolet, A.; Grunder, T. Fundamental study of exit burr formation mechanisms during orthogonal cutting of AlSi aluminium alloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 257, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurich, J.C.; Bohley, M.; Reichenbach, I.G.; Kirsch, B. Surface quality in micro milling: Influences of spindle and cutting parameters. CIRP Ann. 2017, 66, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Bajpai, V.; Singh, R. Burr height prediction of Ti6Al4V in high speed micro-milling by mathematical modeling. Manuf. Lett. 2017, 11, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Chen, M.; Wu, C.; Pei, X.; Qian, J.; Reynaerts, D. Research in minimum undeformed chip thickness and size effect in micro end-milling of potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystal. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2017, 134, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Karpat, Y.; Acar, O.; Kalay, Y.E. Microstructure effects on process outputs in micro scale milling of heat treated Ti6Al4V titanium alloys. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 252, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptaji, K.; Subbiah, S. Burr Reduction of Micro-milled Microfluidic Channels Mould Using a Tapered Tool. Procedia Eng. 2017, 184, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, B.Z.; Takács, M. Experimental investigation and optimisation of the micro milling process of hardened hot-work tool steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 106, 5289–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Yu, T. Study on Surface Integrity and Surface Roughness Model of Titanium Alloy TC21 Milling Considering Tool Vibration. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Wei, C.; Pan, P.; Wang, J.; Wan, Y.; Peng, C.; Hao, X. Study on the influence of PCD micro milling tool edge radius on the surface quality of deep and narrow grooves. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 131, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, B.; An, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Lu, W.; Zhu, L.; Liu, C. Recent advance in laser powder bed fusion of Ti–6Al–4V alloys: Microstructure, mechanical properties and machinability. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2446952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Wu, D.; Zhang, S.; Qin, X.; Jiang, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Sheng, L. Optimized mechanical properties of the hot forged Ti–6Al–4V alloy by regulating multiscale microstructure via laser shock peening. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2024, 201, 104192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Huang, F.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J. Research on the welding strength and V-shape joint structure in the welding of PCD micro tools. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 132, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmael, M.; Memarzadeh, A. A Review on Recent Achievements and Challenges in Electrochemical Machining of Tungsten Carbide. Arch. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2023, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vipindas, K.; Anand, K.N.; Mathew, J. Effect of cutting edge radius on micro end milling: Force analysis, surface roughness, and chip formation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 97, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhao, X.; Wu, X. Experimental study on the wire electrical discharge machining of PCD with different grain sizes. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 155, 112331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Jing, X.; Ehmann, K.F.; Cao, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, D. Modeling of cutting forces in micro end-milling. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 31, 844–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Peng, F.Y.; Yan, R.; Zhu, Z.; Li, B. Experimental study of the effect of tool orientation on cutter deflection in five-axis filleted end dry milling of ultrahigh-strength steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 81, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, M.J.B.; Bordatchev, E.V. Experimental study of the effect of tool orientation in five-axis micro-milling of brass using ball-end mills. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 67, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.K.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Singh, R.K. Effect of lubrication on machining response and dynamic instability in high-speed micromilling of Ti-6Al-4V. J. Manuf. Process. 2017, 28, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.; Patra, K.; Singh, V.K.; Gupta, M.K.; Song, Q.; Mia, M.; Pimenov, D.Y. Influences of TiAlN coating and limiting angles of flutes on prediction of cutting forces and dynamic stability in micro milling of die steel (P-20). J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 278, 116500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afazov, S.M.; Ratchev, S.M.; Segal, J.; Popov, A.A. Chatter modelling in micro-milling by considering process nonlinearities. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2012, 56, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-M.; Mu, A.-L.; Wang, Y.-X.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, H. A Study on the Influence of Milling Parameters on the Properties of TC18 Titanium Alloy. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2020, 12, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, J.C.; Resendiz, J.R.; Thenozhi, S.; Szalay, T.; Jacso, A.; Takacs, M. Frequency and Time-Frequency Analysis of Cutting Force and Vibration Signals for Tool Condition Monitoring. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 6400–6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.; Singh, R. Chatter stability prediction in high-speed micromilling of Ti6Al4V via finite element based microend mill dynamics. Adv. Manuf. 2018, 6, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Uhlmann, E.; Oberschmidt, D.; Sung, C.F.; Perfilov, I. Critical depth of cut and asymptotic spindle speed for chatter in micro milling with process damping. CIRP Ann. 2016, 65, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, M.H.M.; Duduch, J.G.; Jasinevicius, R.G. Minimum chip thickness determination by means of cutting force signal in micro endmilling. Precis. Eng. 2018, 51, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, F.B.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Coelho, R.T.; de Souza, A.F. Size effect and minimum chip thickness in micromilling. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2015, 89, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.; Patra, K.; Szalay, T.; Dyakonov, A.A. Determination of minimum uncut chip thickness and size effects in micro-milling of P-20 die steel using surface quality and process signal parameters. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 106, 4675–4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Y. Modeling and Simulation for Micromilling Mechanisms. Procedia Eng. 2017, 174, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Qian, X.; Chen, H.; Gao, F.; Chen, T. Development of a Staggered PCD End Mill for Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, S. Effects of cutting conditions on the milling process of titanium alloy Ti6Al4V. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 77, 2235–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Sun, R.; Roy, A.; Silberschmidt, V.V. Improved analytical prediction of chip formation in orthogonal cutting of titanium alloy Ti6Al4V. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2017, 133, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, T.; Patra, K.; Dyakonov, A.A. Modeling Cutting Force in Micro-Milling of Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy. Procedia Eng. 2015, 129, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, T.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J. Improved analytical prediction of burr formation in micro end milling. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 151, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquard, R.; D’Acunto, A.; Laheurte, P.; Dudzinski, D. Micro-end milling of NiTi biomedical alloys, burr formation and phase transformation. Precis. Eng. 2014, 38, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, M.; Bajpai, V.; Singh, N.K. Recent advances in characterization, modeling and control of burr formation in micro-milling. Manuf. Lett. 2017, 13, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Qian, J.; He, N.; Reynaerts, D. Research on the ploughing force in micro milling of soft-brittle crystals. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 155, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.W.; Patowari, P.K.; Sahoo, C.K. Machining efficiency and geometrical accuracy on micro-EDM drilling of titanium alloy. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2024, 39, 1380–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 4.51 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | 110 |

| Poisson ratio | 0.34 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/mK) | 7.95 |

| Tensile strength (GPa) | 1.01 |

| Yield strength (GPa) | 0.88 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Diameter D (mm) | 2.0 |

| Cutting edge length Lc (mm) | 6.0 |

| Rake angle (°) | 0 |

| Flank angle (°) | 7 |

| Bottom inclination angle (°) | 15 |

| Tool tip corner radius rε (μm) | 20 |

| Tool cutting edge radius rβ (μm) | 4 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Milling depth ap (μm) | 60, 90, 120, 150 |

| Feed per tooth fz (μm/z) | 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Cutting speed vc (m/min) | 31, 44, 57, 69 |

| No. | Cutting Parameters | Milling Forces | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milling Depth ap (μm) | Feed Per Tooth fz (μm/z) | Cutting Speed vc (m/min) | Tangential Force F(P-V)x (N) | Radial Force F(P-V)y (N) | Axial Force F(P-V)z (N) | Milling Force F(P-V) (N) | |

| 1 | 60 | 2 | 31 | 2.10 | 2.34 | 1.77 | 3.61 |

| 2 | 60 | 3 | 44 | 3.21 | 2.51 | 2.82 | 4.96 |

| 3 | 60 | 4 | 57 | 3.73 | 3.69 | 3.76 | 6.45 |

| 4 | 60 | 5 | 69 | 3.68 | 4.58 | 4.02 | 7.12 |

| 5 | 90 | 2 | 44 | 5.93 | 4.70 | 4.41 | 8.76 |

| 6 | 90 | 3 | 31 | 5.01 | 6.59 | 5.53 | 9.96 |

| 7 | 90 | 4 | 69 | 5.95 | 6.14 | 6.85 | 10.95 |

| 8 | 90 | 5 | 57 | 12.83 | 6.08 | 7.64 | 16.13 |

| 9 | 120 | 2 | 57 | 19.17 | 8.77 | 13.45 | 25.00 |

| 10 | 120 | 3 | 69 | 19.70 | 19.20 | 20.67 | 34.41 |

| 11 | 120 | 4 | 31 | 15.96 | 22.89 | 21.23 | 35.07 |

| 12 | 120 | 5 | 44 | 33.57 | 15.11 | 23.56 | 43.70 |

| 13 | 150 | 2 | 69 | 16.62 | 15.77 | 17.95 | 29.11 |

| 14 | 150 | 3 | 57 | 29.71 | 13.78 | 25.91 | 41.76 |

| 15 | 150 | 4 | 44 | 28.32 | 15.01 | 21.12 | 38.39 |

| 16 | 150 | 5 | 31 | 11.34 | 16.65 | 16.15 | 25.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, L.; Zhang, K.; Liu, B.; Jiang, F.; Wu, X.; Zhai, L.; Huang, F.; You, W.; Xu, T.; Zhang, S.; et al. Experimental Investigation on Cutting Force and Hole Quality in Milling of Ti-6Al-4V. Micromachines 2026, 17, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010019

Zhu L, Zhang K, Liu B, Jiang F, Wu X, Zhai L, Huang F, You W, Xu T, Zhang S, et al. Experimental Investigation on Cutting Force and Hole Quality in Milling of Ti-6Al-4V. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Laifa, Kechuang Zhang, Bin Liu, Feng Jiang, Xian Wu, Lulu Zhai, Fuping Huang, Wenbiao You, Tongtong Xu, Shanqin Zhang, and et al. 2026. "Experimental Investigation on Cutting Force and Hole Quality in Milling of Ti-6Al-4V" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010019

APA StyleZhu, L., Zhang, K., Liu, B., Jiang, F., Wu, X., Zhai, L., Huang, F., You, W., Xu, T., Zhang, S., Guo, R., Xue, Y., & Chen, X. (2026). Experimental Investigation on Cutting Force and Hole Quality in Milling of Ti-6Al-4V. Micromachines, 17(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010019