Three-Dimensional Combustion Field Temperature Measurement Based on Planar Array Sensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Models and Methods

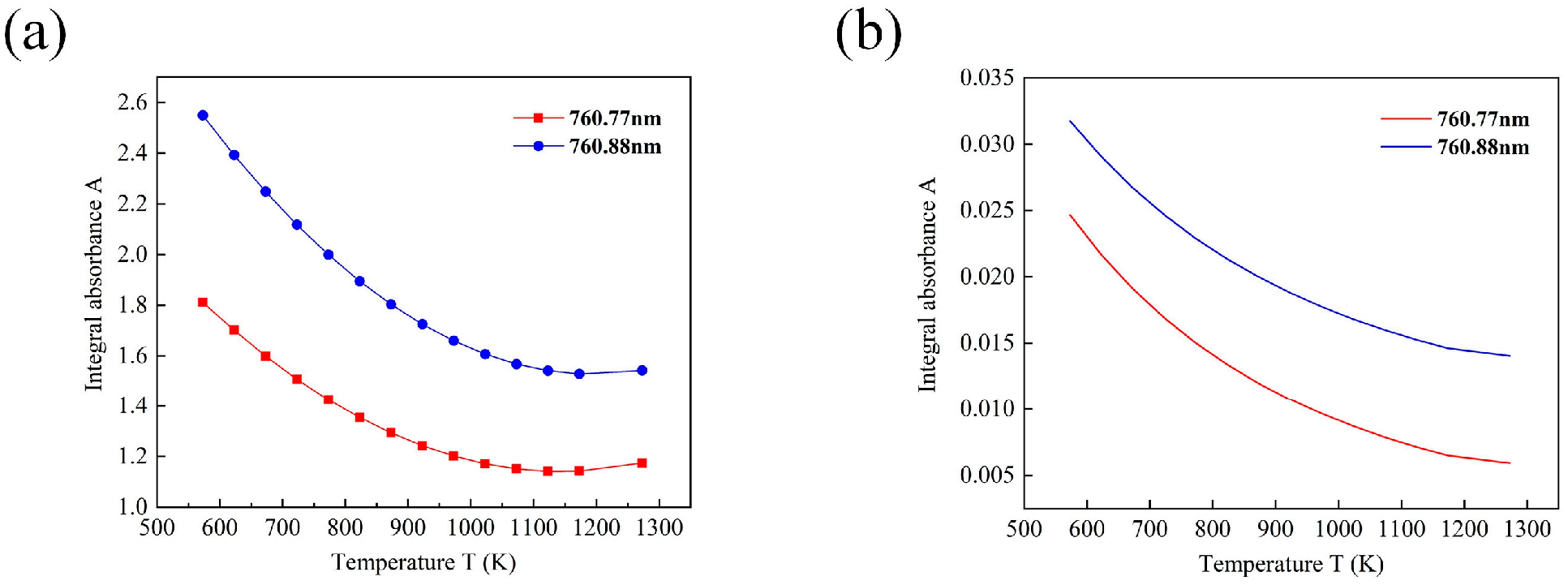

2.1. Absorption Spectrum Model

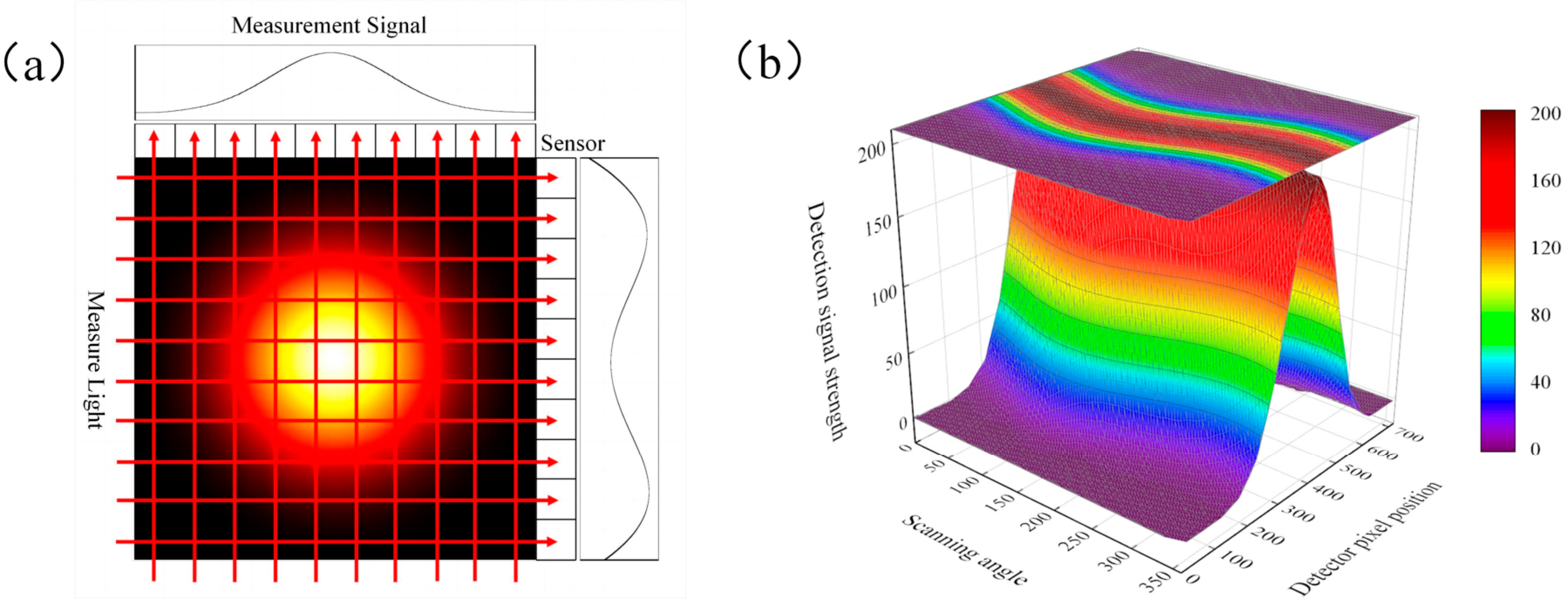

2.2. Algorithm Model

- (1)

- Filter the projection p(x,φ) measured at a fixed viewing angle φ to obtain the filtered projection g(x,φ);

- (2)

- Back-project g(x,φ) under each φ across all points on the ray satisfying x = −cos(θ − φ);

- (3)

- Accumulate the back-projection values in step 2 for all 0 < φ ≤ π, and finally obtain the reconstructed image.

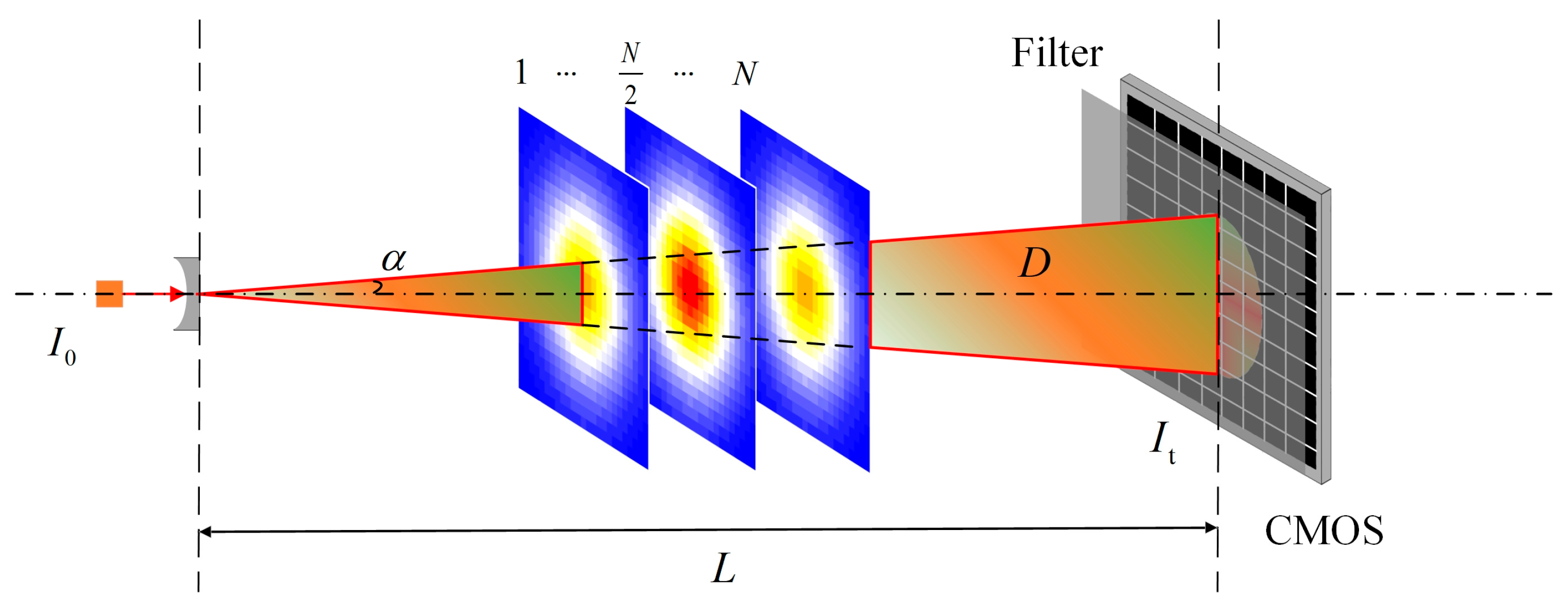

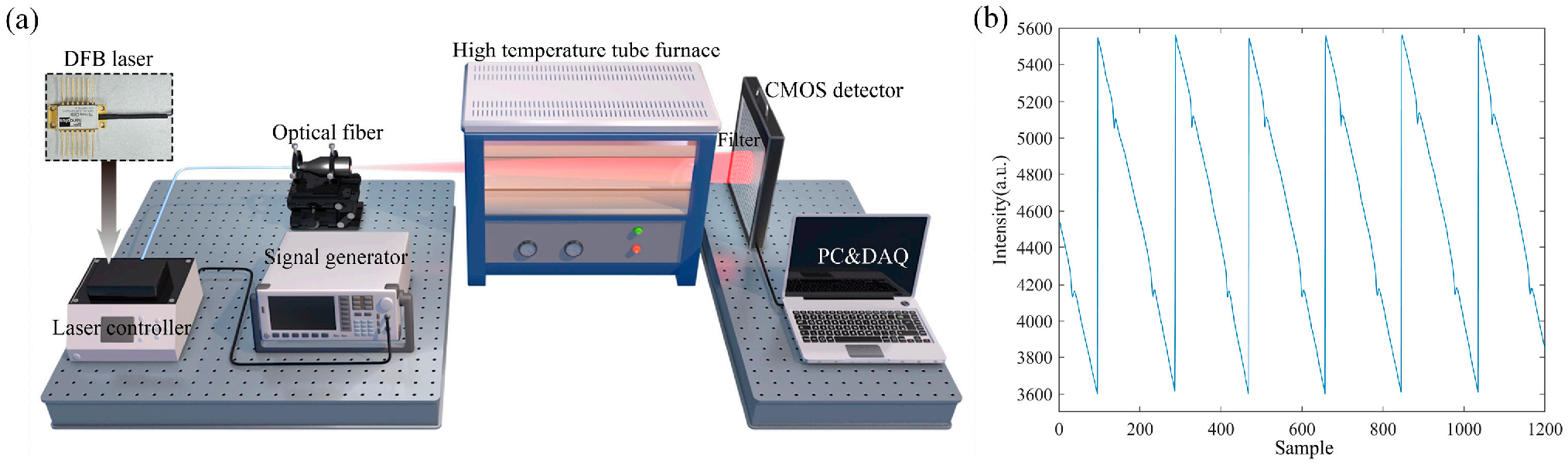

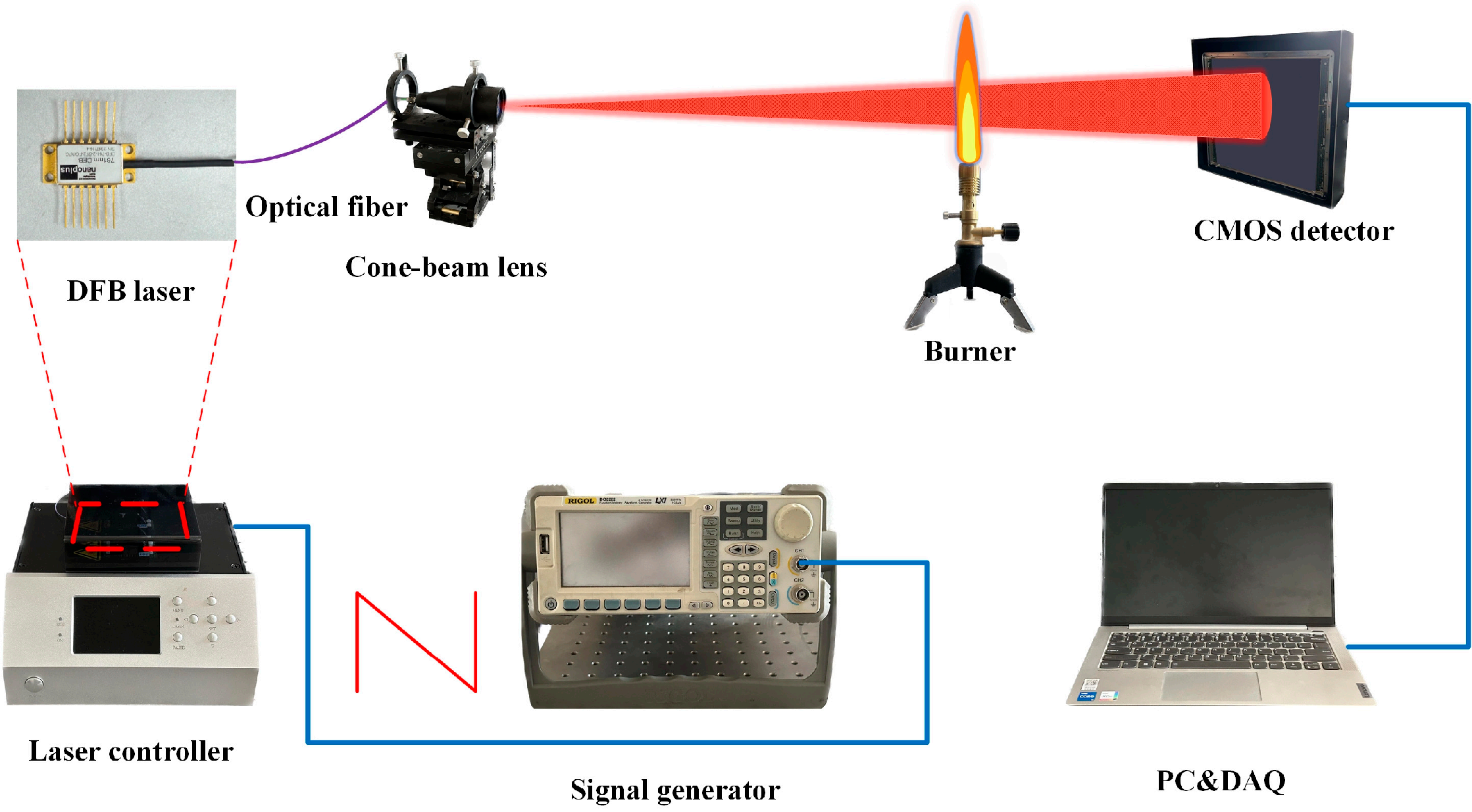

2.3. TDLAT Measurement System and Calibration Experiment

3. Numerical Simulations and Experiments

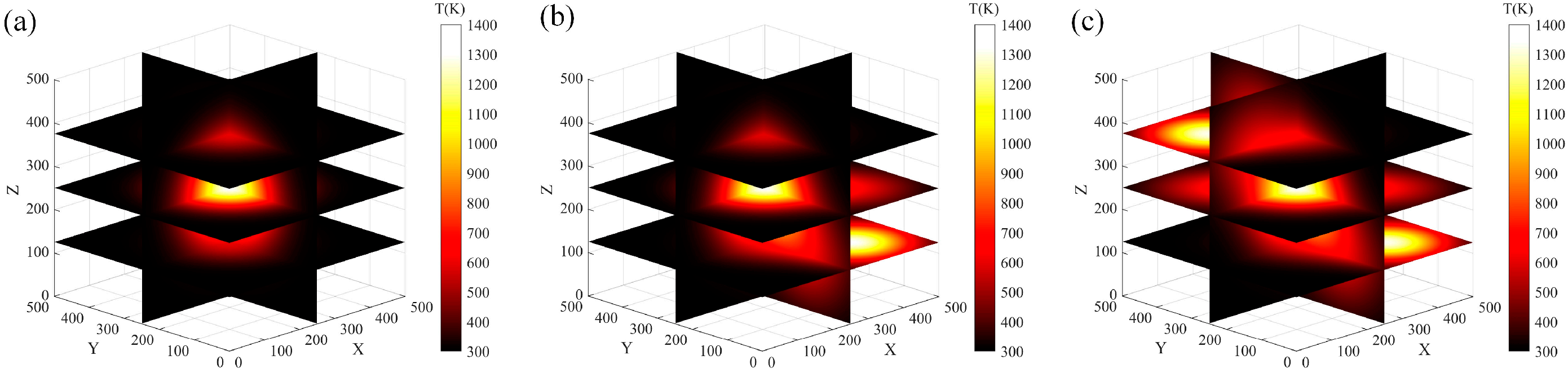

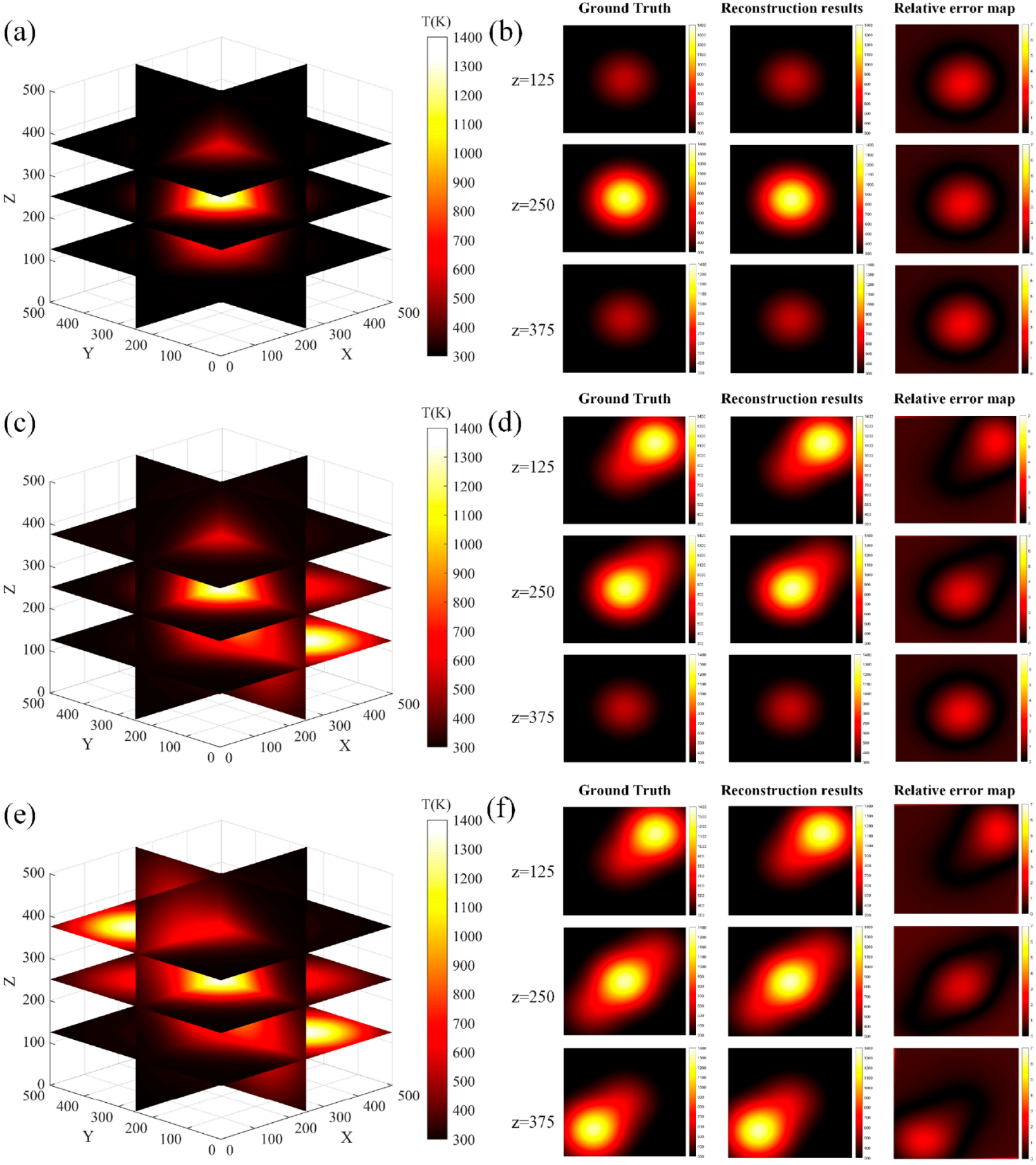

3.1. Numerical Simulations

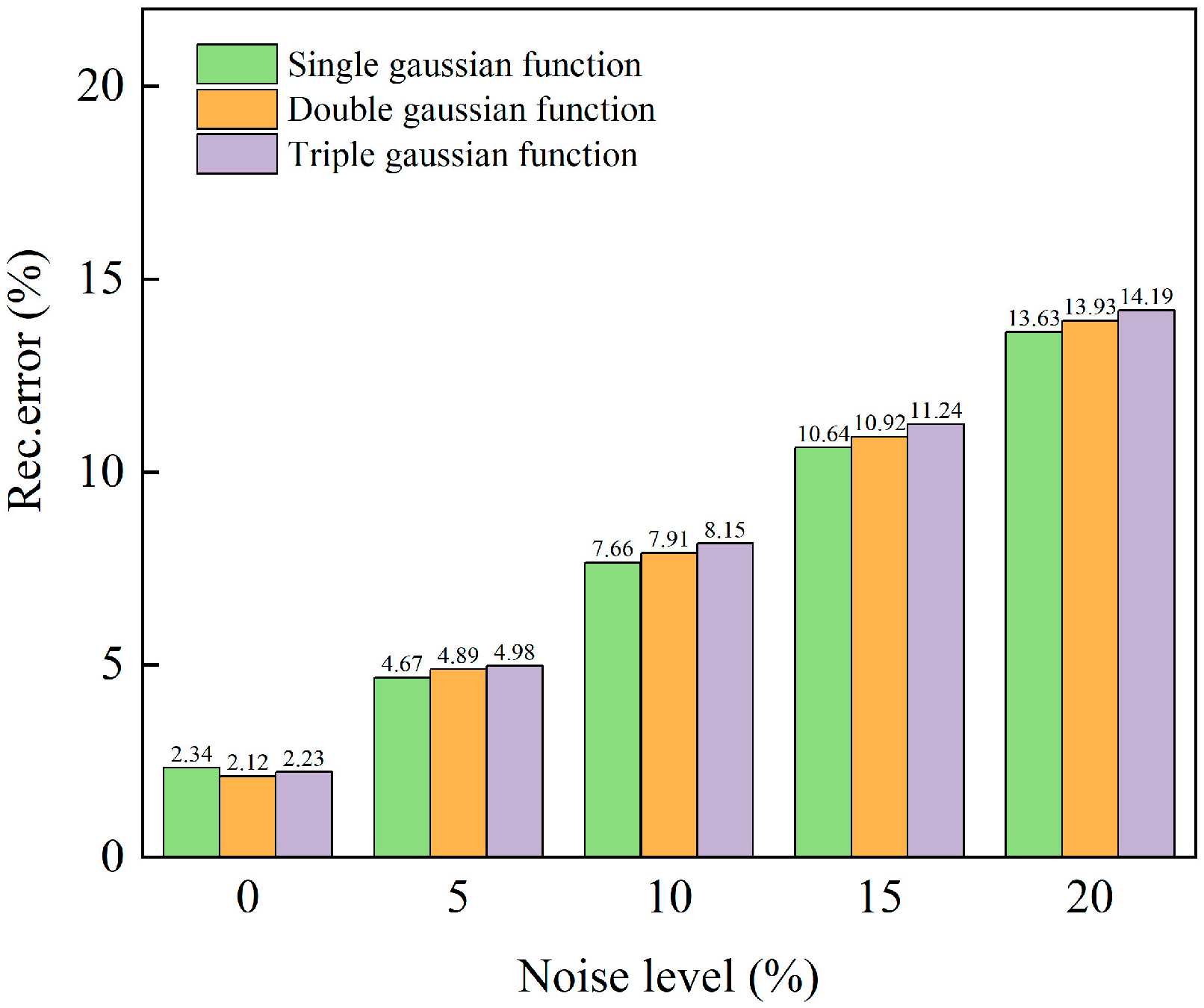

3.2. Anti-Noise Experiments

3.3. Combustion Flame Experiments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Araújo, T.P.; Mondelli, C.; Agrachev, M.; Zou, T.; Willi, P.O.; Engel, K.M.; Grass, R.N.; Stark, W.J.; Safonova, O.V.; Jeschke, G.; et al. Flame-made ternary Pd-In2O3-ZrO2 catalyst with enhanced oxygen vacancy generation for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hao, X.; Pan, B.; Huang, X.; Sun, H.; Pei, P. Spectroscopic measurement of the two-dimensional flame temperature based on a perovskite single photodetector. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 8098–8109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Cao, Z.; Wen, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L. A binary valued reconstruction algorithm for discrete TDLAS tomography of dynamic flames. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Liu, Y.; Fan, H.; Huang, X.; Nakamura, Y. Fluctuation and extinction of laminar diffusion flame induced by external acoustic wave and source. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Zhong, J.; Feng, K.; Wu, Z.; Du, B.; He, J.; Li, Z.; He, L.; et al. Grave-to-cradle upcycling of Ni from electroplating wastewater to photothermal CO2 catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Choi, C.W.; Puri, I.K. Temperature measurements in steady two-dimensional partially premixed flames using laser interferometric holography. Combust. Flame 2000, 120, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Shrivastav, A.M.; Kumar, A.; Jha, R. Non-graphene two-dimensional nanosheets for temperature sensing based on microfiber interferometric platform: Performance analysis. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 289, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhu, G.; Zeng, Y.; Yu, G.; Yang, Y. A femtosecond time-resolved coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy thermometry for steady-state high-temperature flame. Combust. Flame 2022, 242, 112166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Chang, Z.; Lowe, A.; Thomas, L.M.; Masri, A.R.; Lucht, R.P. CARS thermometry in laminar sooting ethylene-air co-flow diffusion flames with nitrogen dilution. Combust. Flame 2019, 208, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Cao, Z.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, H.; Xu, L. Frequency-division multiplexing and main peak scanning WMS method for TDLAS tomography in flame monitoring. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 9087–9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Fu, G.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Enemali, G.; Liu, C. A quality-hierarchical temperature imaging network for TDLAS tomography. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hao, X.; Xue, B.; Tai, B.; Zhou, H. Two-dimensional flame temperature and emissivity distribution measurement based on element doping and energy spectrum analysis. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 200863–200874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hao, X.; Pan, B.; Huang, X.; Sun, H.; Pei, P. Perovskite single-detector visible-light spectrometer. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempema, N.J.; Long, M.B. Effect of soot self-absorption on color-ratio pyrometry in laminar coflow diffusion flames. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.J.; Kwon, H.; Kastengren, A.L.; Pfefferle, L.D.; Sikes, T.; Tranter, R.S.; Xuan, Y.; McEnally, C.S. In situ temperature measurements in sooting methane/air flames using synchrotron x-ray fluorescence of seeded krypton atoms. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obreht, I.; De Vleeschouwer, D.; Wörmer, L.; Kucera, M.; Varma, D.; Prange, M.; Laepple, T.; Wendt, J.; Nandini-Weiss, S.D.; Schulz, H.; et al. Last Interglacial decadal sea surface temperature variability in the eastern Mediterranean. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenstein, C.S.; Spearrin, R.M.; Jeffries, J.B.; Hanson, R.K. Infrared laser-absorption sensing for combustion gases. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 60, 132–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, L. Laser absorption spectroscopy for combustion diagnosis in reactive flows: A review. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2019, 54, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xu, L.; Huang, A.; Gao, X.; Luo, X.; Zhang, H.; Chang, H.; Cao, Z. A WMS based TDLAS tomographic system for distribution retrievals of both gas concentration and temperature in dynamic flames. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 4179–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Deguchi, Y.; Kamimoto, T.; Tainaka, K.; Tanno, K. Pulverized coal combustion application of laser-based temperature sensing system using computed tomography—Tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy (CT-TDLAS). Fuel 2020, 268, 117370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevrlý, V.; Dostál, M.; Klečka, V.; Bitala, P.; Válek, V.; Vašinek, M.; Blejchař, T.; Suchánek, J.; Zelinger, Z.; Wild, J. TDLAS-based in situ diagnostics for the combustion of preheated ultra–lean dimethyl ether/air mixtures. Fuel 2020, 263, 116652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchener, J.; Millington-Smith, D.; Goldsack, C.; Harrison, G.; Dunning, A.; Ai, X.; Reed, M. Single photon Lidar gas imagers for practical and widespread continuous methane monitoring. Appl. Energy 2022, 306, 118086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.C.; Cao, L.; Chen, X.L.; Yang, B.; Liu, P. TDLAS online measurement system for plume temperature of ramjet engine. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2021, 42, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bong, C.; Lee, J.; Sun, H.; Yoo, J.; Bak, M.S. TDLAS measurements of temperature and water vapor concentration in a flameless MILD combustor. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 055204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Wang, Y. Spatially and temporally resolved temperature measurements in counterflow flames using a single interband cascade laser. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 37879–37902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, L.; Chen, J.; Cao, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cai, W. Development of a fan-beam TDLAS-based tomographic sensor for rapid imaging of temperature and gas concentration. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 22494–22511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Cao, Z.; Li, F.; Lin, Y.; Xu, L. Flame monitoring of a model swirl injector using 1D tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy tomography. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2017, 28, 054002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cao, Z.; Lin, Y.; Xu, L.; McCann, H. Online cross-sectional monitoring of a swirling flame using TDLAS tomography. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 67, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L. Single spectral line method for TDLAS imaging of temperature and water vapor concentration. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancin, R.J.; Spearrin, R.M.; Goldenstein, C.S. 2D mid-infrared laser-absorption imaging for tomographic reconstruction of temperature and carbon monoxide in laminar flames. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 14184–14198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Ma, D.; Yang, B.; Qiu, C. Preliminary experimental study on combustion characteristics in a solid rocket motor nozzle based on the TDLAS system. Energy 2023, 268, 126741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Bong, C.; Yoo, J.; Bak, M.S. Combined use of TDLAS and LIBS for reconstruction of temperature and concentration fields. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 21121–21133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, C.Z.; Haskell, M.W.; Cauley, S.F.; Sappo, C.; Lapierre, C.D.; Ha, C.G.; Stockmann, J.P.; Wald, L.L. Design of sparse Halbach magnet arrays for Portable MRI using a genetic Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2017, 54, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Xu, Z.; Kan, R.; He, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G. Numerical study of two-dimensional water vapor concentration and temperature distribution of combustion zones using tunable diode laser absorption tomography. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2015, 72, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, J.A.; Heiken, J.P.; Wang, G.; McEnery, K.W.; Schlueter, F.J.; Vannier, M.W. Helical CT: Principles and technical considerations. Radiographics 1994, 14, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbelt, S.; Liebling, M.; Unser, M.A. Filter design for filtered back-projection guided by the interpolation model. In Medical Imaging 2002: Image Processing; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2002; Volume 4684, pp. 806–813. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, I.E.; Rothman, L.S.; Hill, C.; Kochanov, R.V.; Tan, Y.; Bernath, P.F.; Birk, M.; Boudon, V.; Campargue, A.; Chance, K.V.; et al. The HITRAN 2016 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2017, 203, 3–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

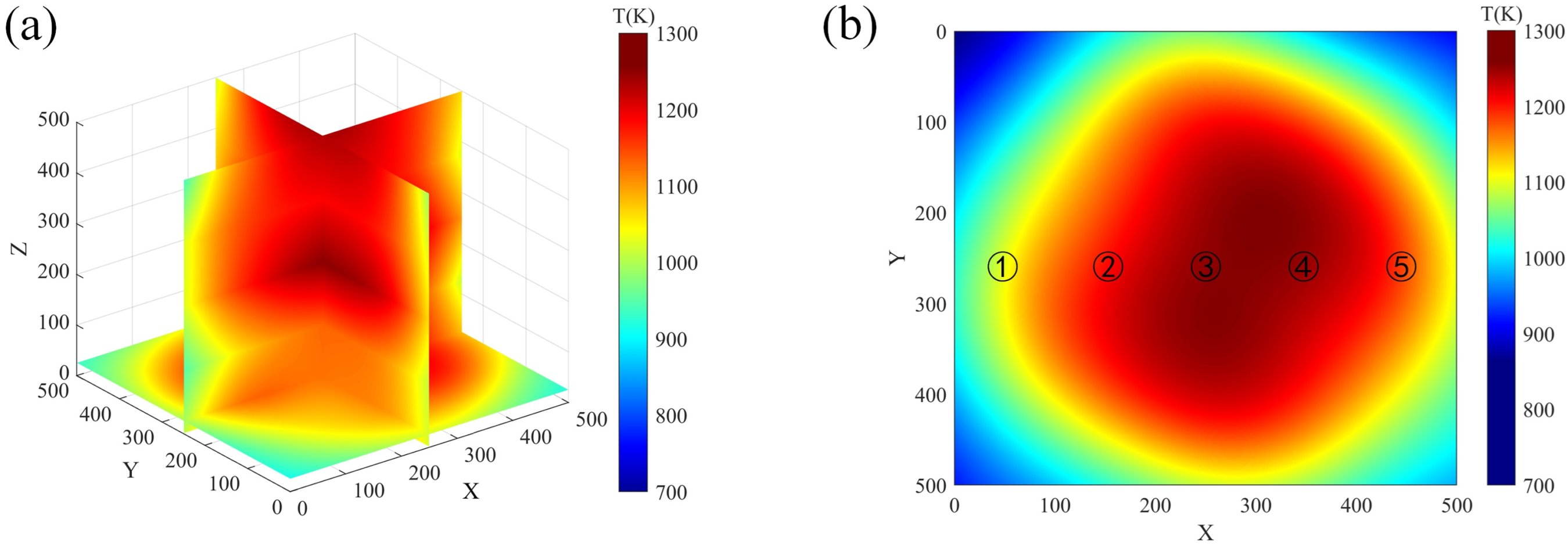

| Position | Thermocouple Measurements (K) | Reconstructed Value (K) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1054 | 1099 | 4.27 |

| 2 | 1143 | 1202 | 5.16 |

| 3 | 1196 | 1252 | 4.68 |

| 4 | 1193 | 1250 | 4.78 |

| 5 | 1126 | 1179 | 4.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bao, Y. Three-Dimensional Combustion Field Temperature Measurement Based on Planar Array Sensors. Micromachines 2026, 17, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010135

Huang X, Li Z, Wang J, Zhang W, Liu Y, Zhang X, Bao Y. Three-Dimensional Combustion Field Temperature Measurement Based on Planar Array Sensors. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010135

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Xiaodong, Zhiling Li, Jia Wang, Wei Zhang, Yang Liu, Xiaoyong Zhang, and Yanan Bao. 2026. "Three-Dimensional Combustion Field Temperature Measurement Based on Planar Array Sensors" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010135

APA StyleHuang, X., Li, Z., Wang, J., Zhang, W., Liu, Y., Zhang, X., & Bao, Y. (2026). Three-Dimensional Combustion Field Temperature Measurement Based on Planar Array Sensors. Micromachines, 17(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010135