Low Temperature Effect of Resistance Strain Gauge Based on Double-Layer Composite Film

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

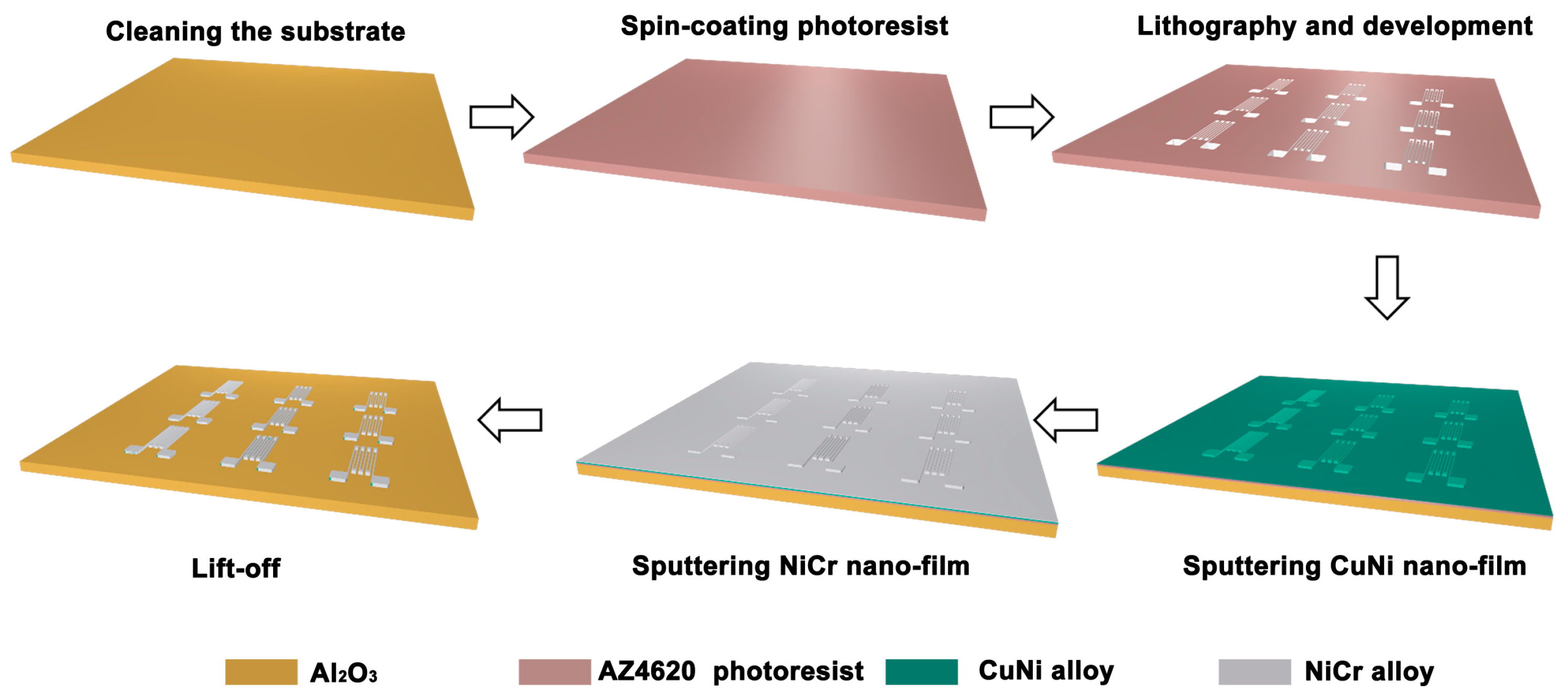

2.2. Fabrication of Double-Layer Composite Film-Based Strain Gauges

2.3. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

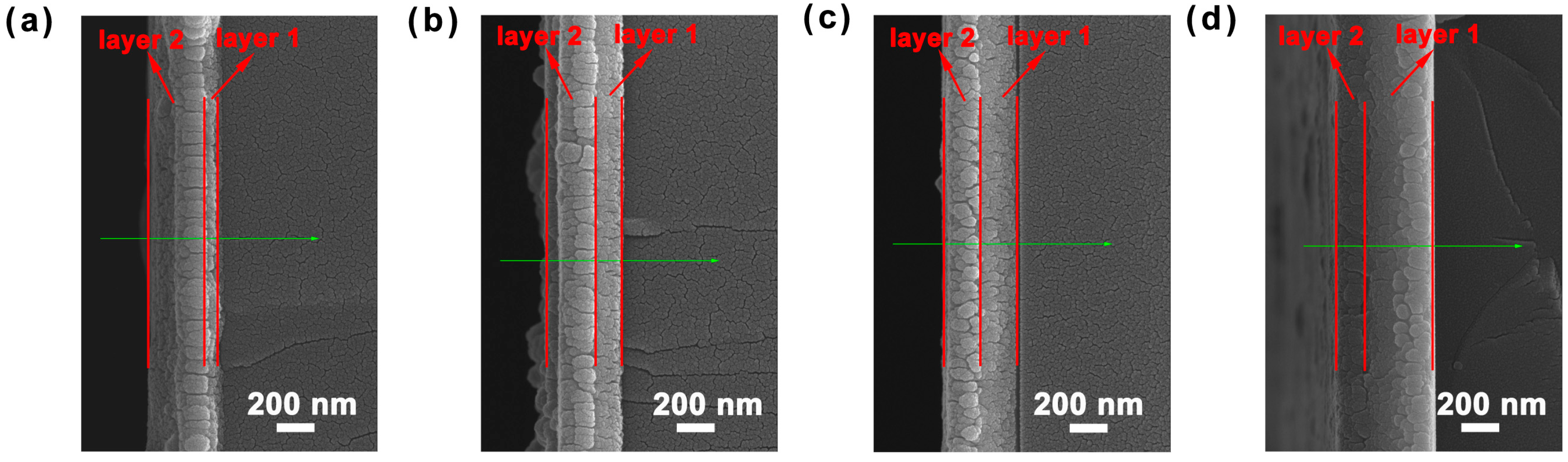

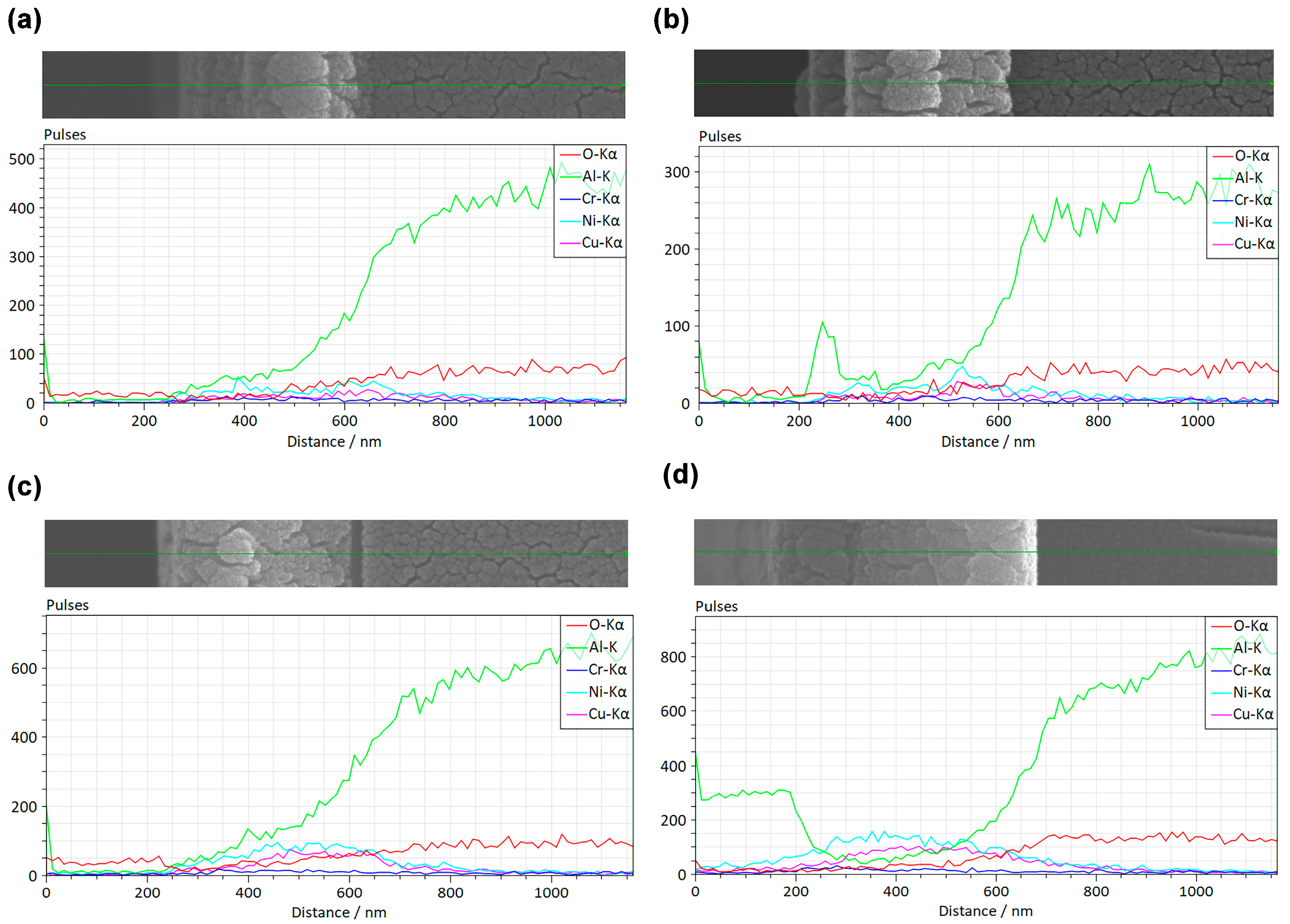

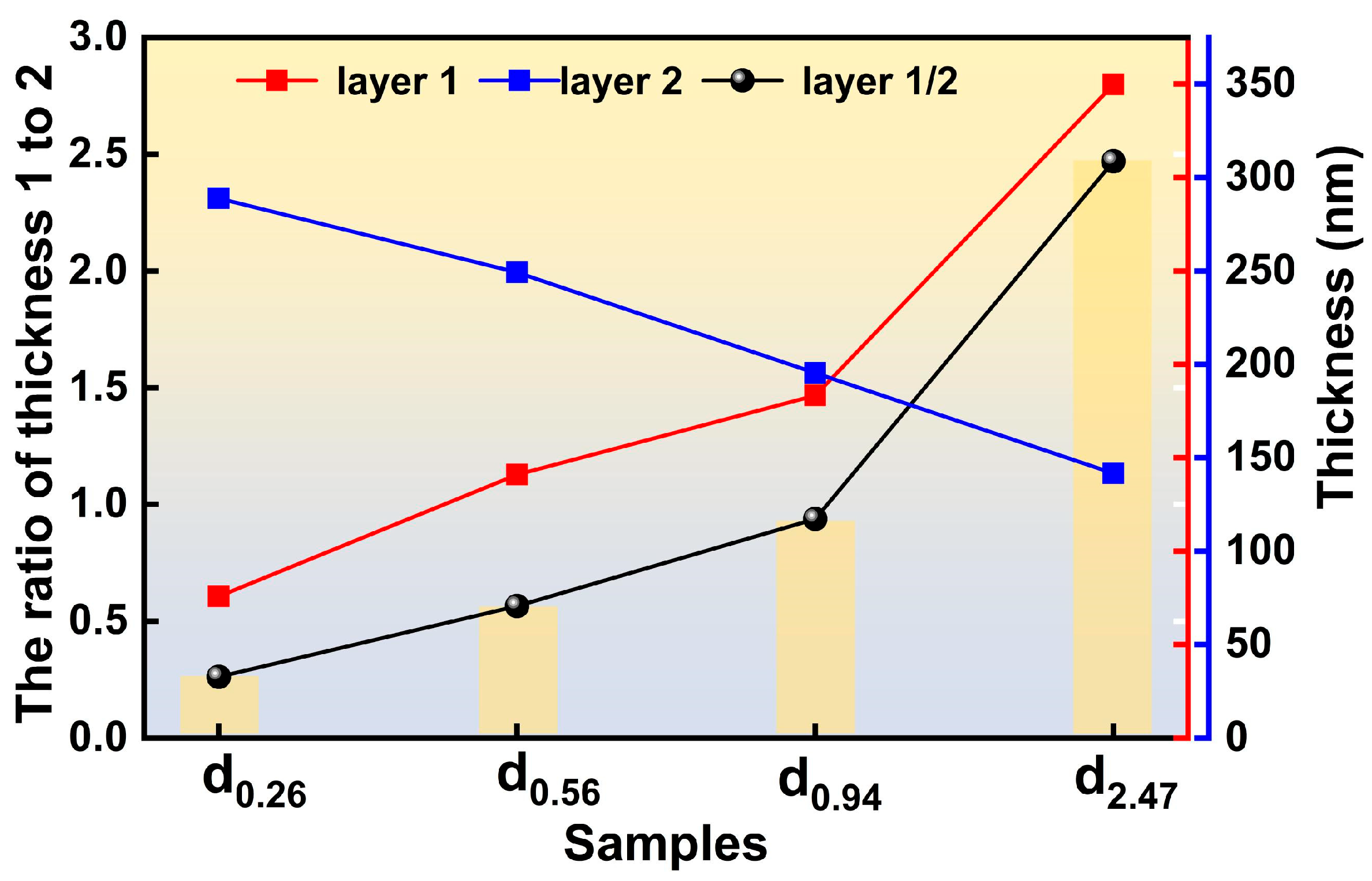

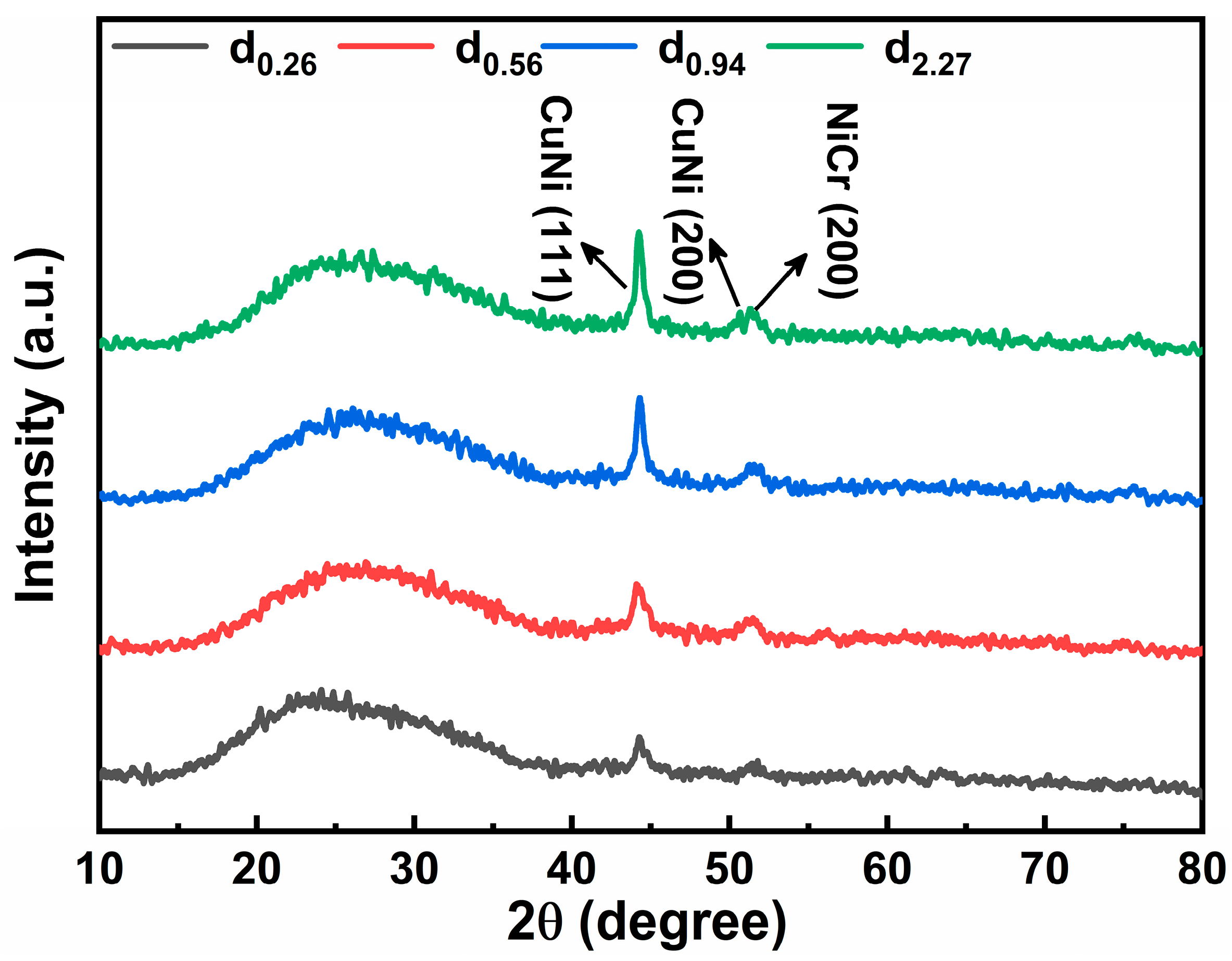

3.1. Characterization of Double-Layer Composite Films

3.2. Theoretical Derivation of Zero TCR for Composite Films

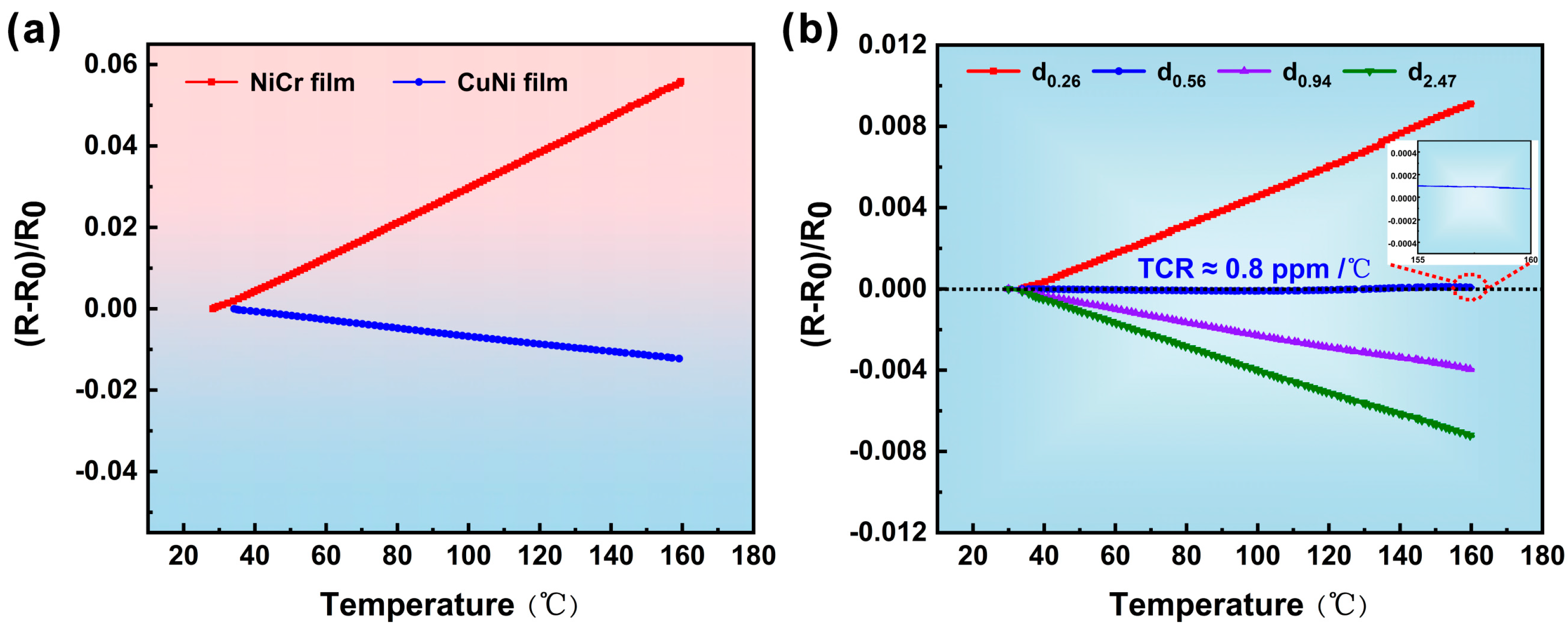

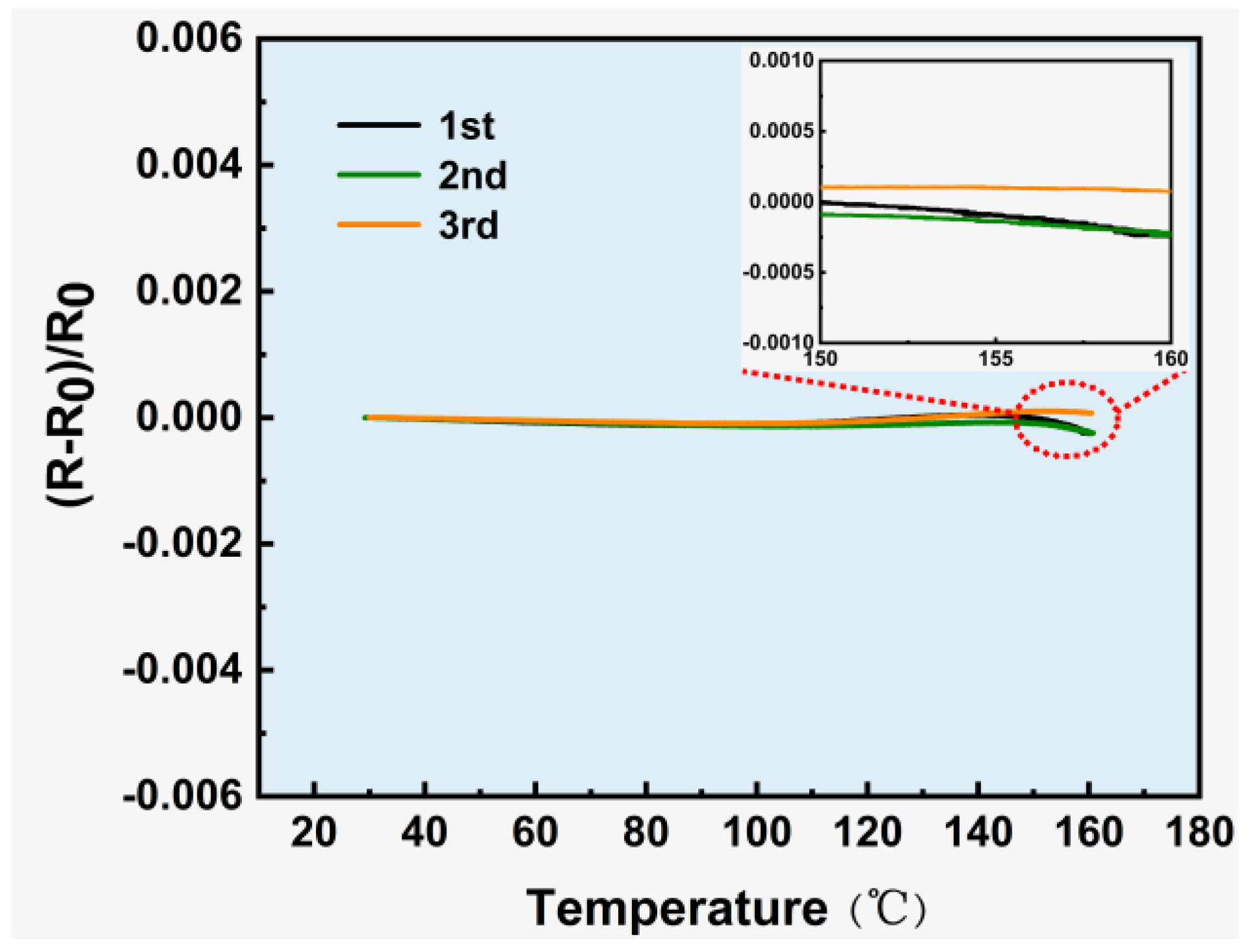

3.3. TCR Characteristics of Composite Film Strain Gauges

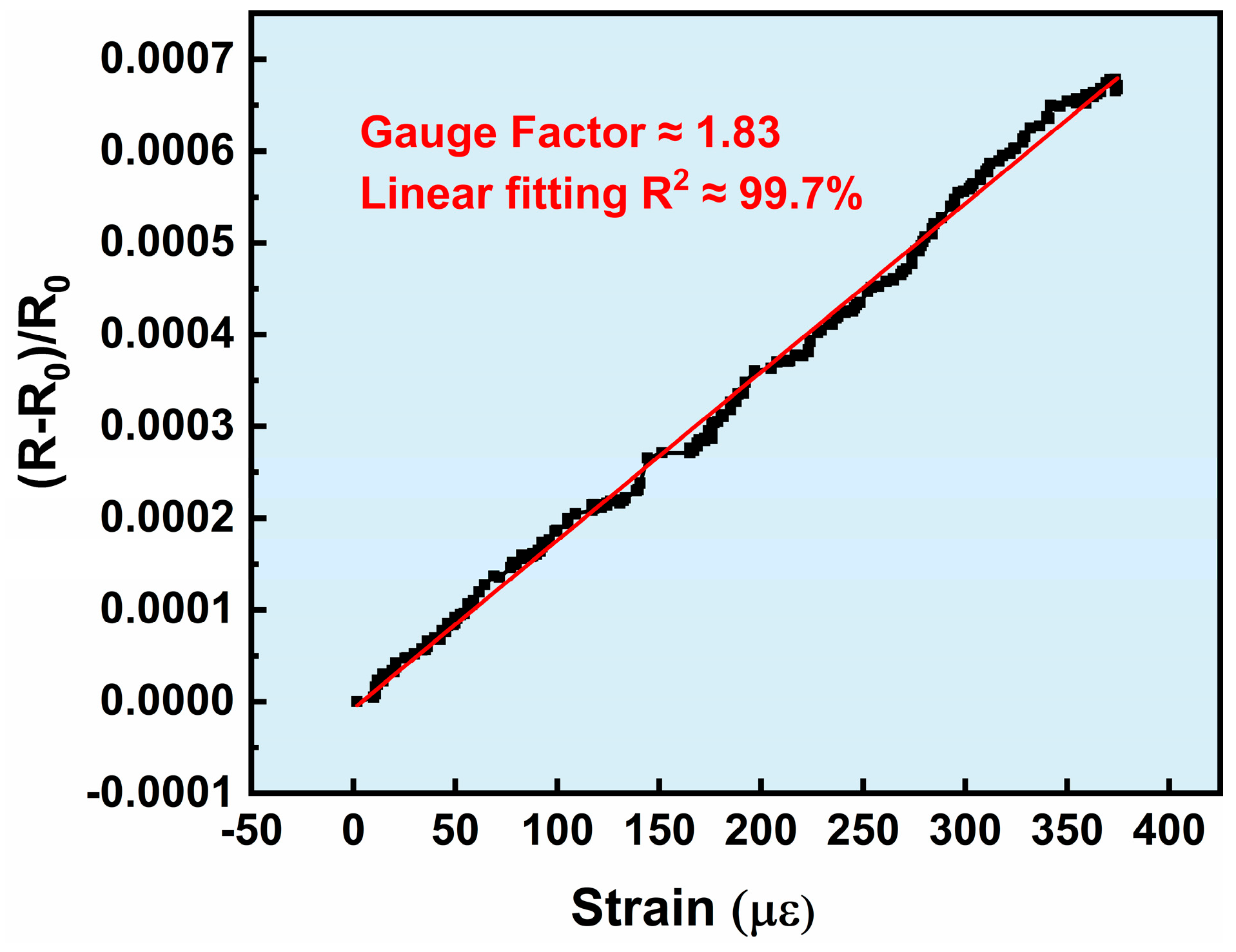

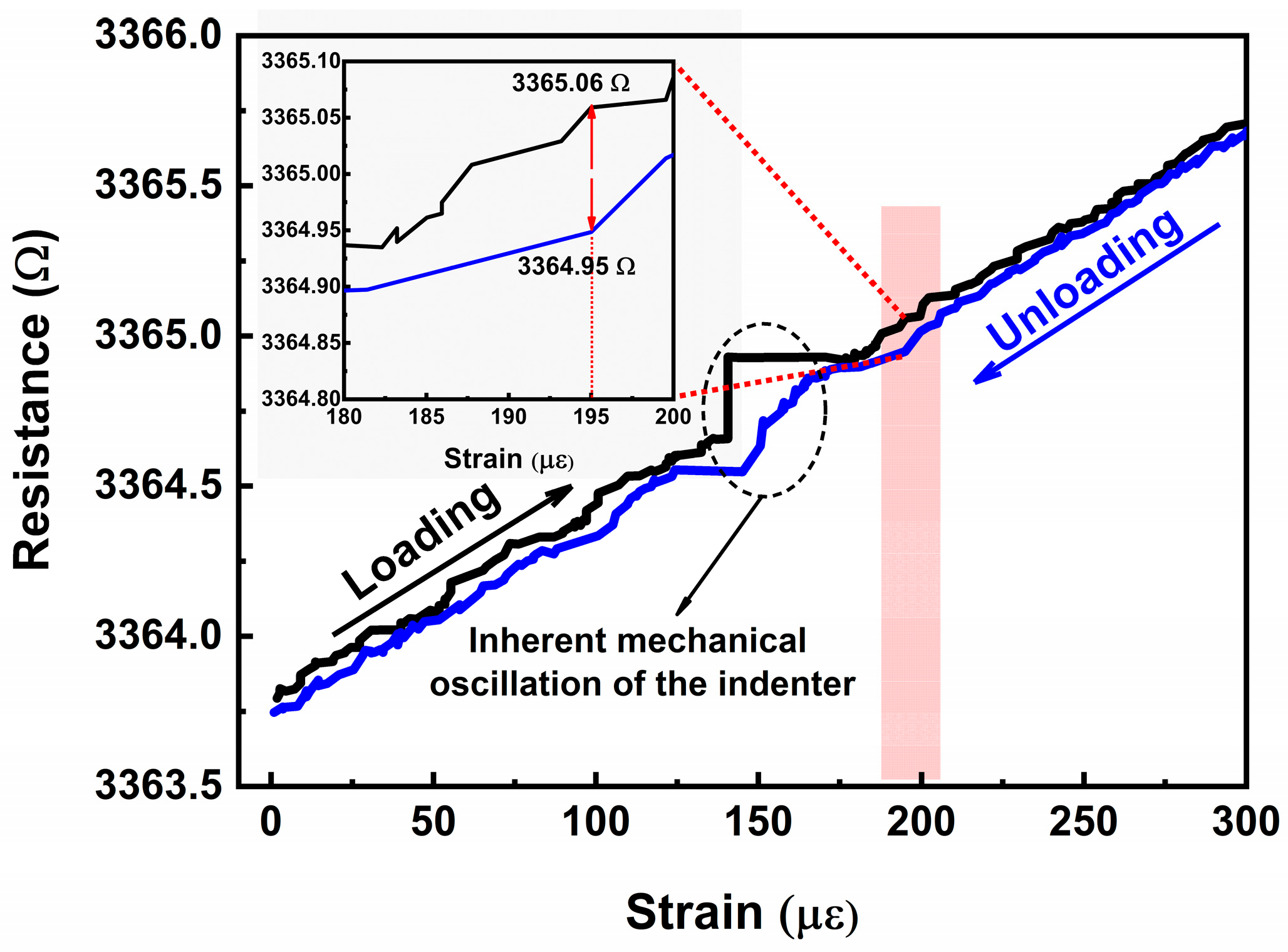

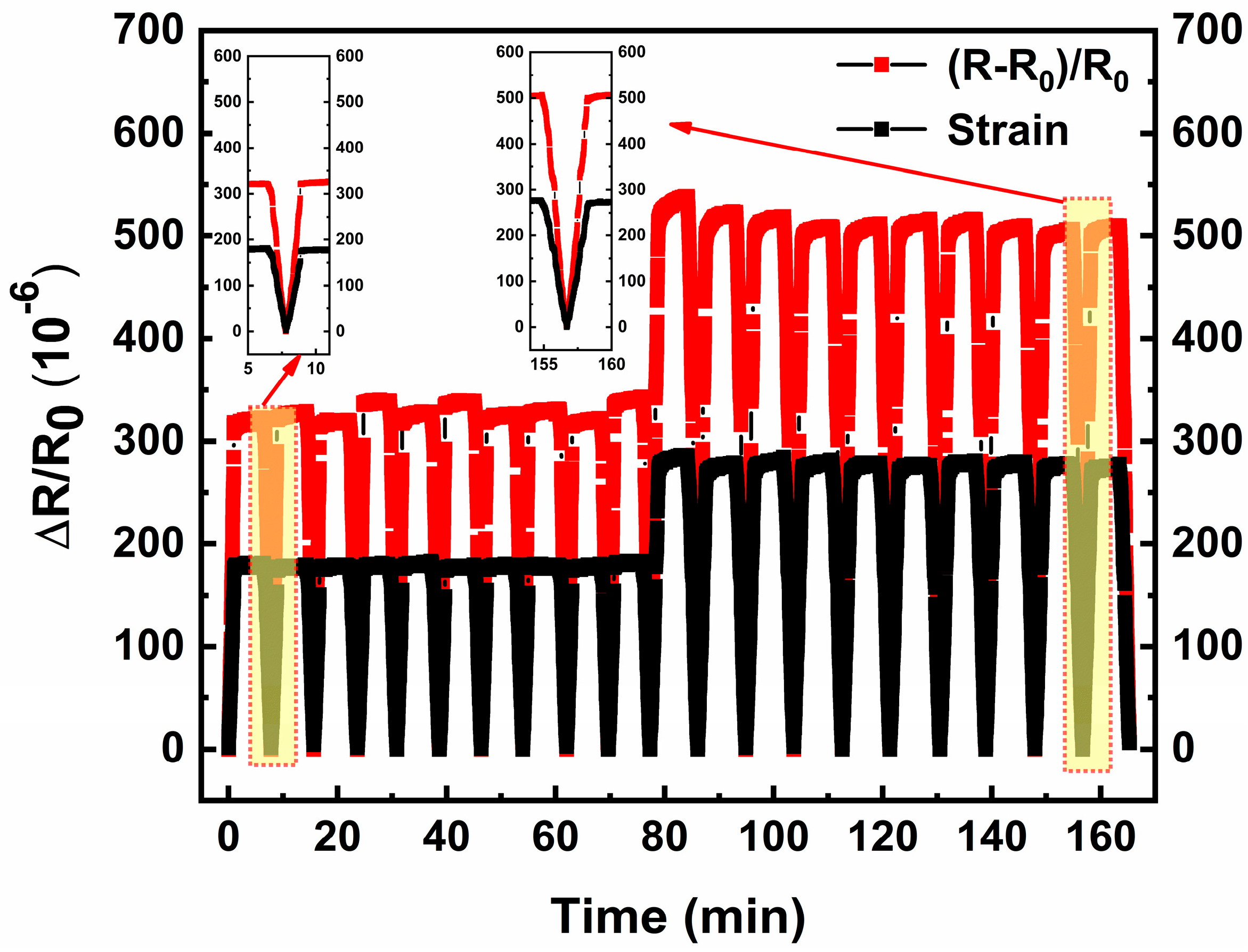

3.4. Strain Response of Composite Strain Gauges

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TCR | Temperature Coefficient of Resistance |

| MEMS | Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems |

| GF | Gauge Factor |

References

- Wu, B.; Lin, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, H. An effective prediction method for bridge long-gauge strain under moving trainloads with experimental verification. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 186, 109855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Gao, Z.; Wu, B.; Zhou, Z. Dynamic and quasi-static signal separation method for bridges under moving loads based on long-gauge FBG strain monitoring. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2019, 38, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Hou, P.; Yang, C.; Yang, N.; Li, K. Damage identification method of box girder bridges based on distributed long-gauge strain influence line under moving load. Sensors 2021, 21, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavan, K.; Ravisankar, K.; Senthil, R.; Sundaram, B.A.; Parivallal, S. Studies on apparent strain using fbg strain sensors for different structural materials. Exp. Tech. 2014, 38, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, C. Thermal and magnetic correlation in apparent strain down to 1.53 K and up to 6 T on strain gauges. Measurement 2018, 128, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xu, T.; Bi, L. Research on compensation method of temperature drift in pressure sensor using double wheatstone-bridge method. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 459, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ni, F.; Liu, H. Design and optimization of wheatstone bridge adjustment circuit for resistive sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 14330–14338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, T.; Kim, S.; Park, S. The temperature compensation of a thermal flow sensor by changing the slope and the ratio of resistances. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2004, 114, 212−218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zymelka, D.; Yamashita, T.; Takamatsu, S.; Itoh, T.; Kobayashi, T. Printed strain sensor with temperature compensation and its evaluation with an example of applications in structural health monitoring. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 56, 05EC02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hu, Z.; Yan, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ye, F.; Sun, B.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Ding, G.; et al. A flexible resistive strain gauge with reduced temperature effect via thermal expansion anisotropic composite substrate. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, H.; Lin, X.; Yao, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Ding, G. Effect of Al2O3/Al bilayer protective coatings on the high-temperature stability of PdCr thin film strain gages. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 759, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X.; Hu, K.; Ding, G. Improved high-temperature performance of PdCr thin-film strain gauges by in-situ grown oxide film. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 708, 163723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ding, G.; Zhang, C. High-temperature PdCr thin-film strain gauge with high gauge factor based on cavity structure. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 9573–9584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K. Dynamic micromechanics on silicon: Techniques and devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1978, 25, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, S.; Friedberger, A.; Seidel, H.; Schmid, U. High temperature measurement set-up for the electro-mechanical characterization of robust thin film systems. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 015007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, O.; Chen, X. A low TCR nanocomposite strain gage for high temperature aerospace applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2007, 2, 624–627. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, S.; Kim, D.; Kang, B.; Yoon, S. The structural and electrical properties of CuNi thin-film resistors grown on AlN substrates for p-type attenuator application. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, G472−G476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, F.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Shen, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Yi, G.; Zhou, X.; Wu, C.; et al. High-temperature thin-film strain sensors with low temperature coefficient of resistance and high sensitivity via direct ink writing. Nano. Prec. Eng. 2024, 8, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Zhang, C.; Pang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, M. Fabrication and performance investigation of karma alloy thin film strain Gauge. J. Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ. (Sci.) 2021, 26, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, N.; Lin, J.; Chen, H. Annealing effect on the electrical properties and composition of a NiCrAl thin film resistor. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 54, 125502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lu, N. Gauge factor and stretchability of silicon-on-polymer strain gauges. Sensors 2013, 13, 8577–8594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Hu, Z.; Ye, F.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Low Temperature Effect of Resistance Strain Gauge Based on Double-Layer Composite Film. Micromachines 2026, 17, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010114

Li M, Hu Z, Ye F, Wang J, Yang Z. Low Temperature Effect of Resistance Strain Gauge Based on Double-Layer Composite Film. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010114

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Mengqiu, Zhiyuan Hu, Fengming Ye, Jiaxiang Wang, and Zhuoqing Yang. 2026. "Low Temperature Effect of Resistance Strain Gauge Based on Double-Layer Composite Film" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010114

APA StyleLi, M., Hu, Z., Ye, F., Wang, J., & Yang, Z. (2026). Low Temperature Effect of Resistance Strain Gauge Based on Double-Layer Composite Film. Micromachines, 17(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010114