Modeling and Simulation of Multi-Pulse Femtosecond Laser Ablation of WC-6Co Cemented Carbide

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Femtosecond Laser Experimental Setup

2.1. Femtosecond Laser and Optical Path System

2.2. Measuring Devices

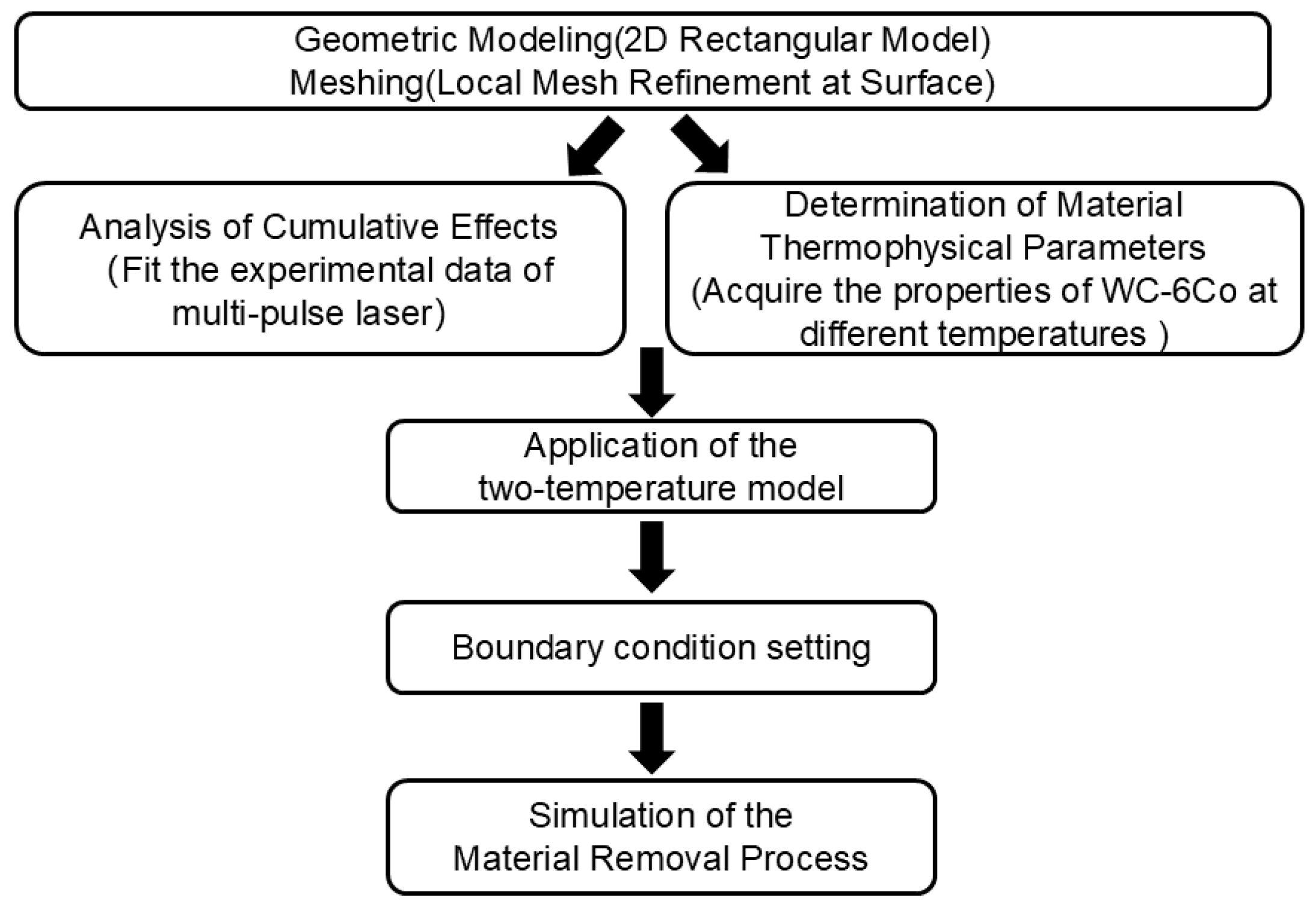

3. Femtosecond Laser Multi-Pulse Ablation Modeling

3.1. Geometric Modeling and Meshing

- (1)

- The laser beam used has an ideal Gaussian distribution in both the spatial and temporal domains.

- (2)

- The workpiece material is homogeneous and isotropic.

- (3)

- The surface of the workpiece is considered smooth and flat.

- (4)

- The material does not absorb part of the laser light that has been reflected out.

3.2. Cumulative Effects

3.3. Thermophysical Parameters of Materials

3.4. Two-Temperature Model

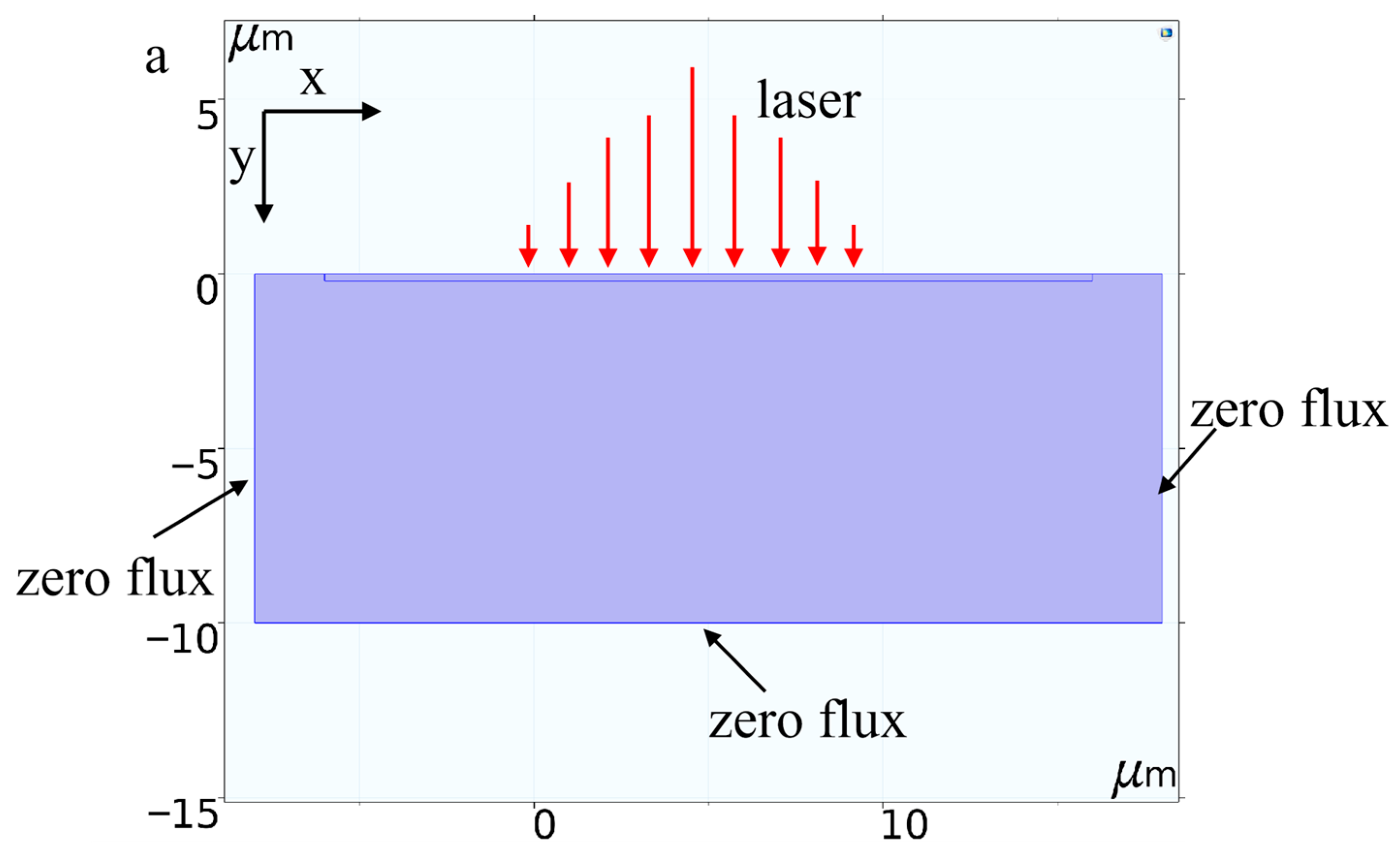

3.5. Boundary Condition Setting

- (1)

- For the top surface, the boundary evolves dynamically due to the material ablation process. As the material is removed, the thermal energy contained within the ablated volume is carried away, acting as the primary heat dissipation mechanism. Due to the extremely short laser–material interaction time, heat losses via convection and radiation are negligible compared to the vaporization energy. Therefore, no additional thermal boundary conditions (e.g., convective or radiative heat flux) were imposed on the top surface.

- (2)

- Adiabatic (zero-flux) boundary conditions are applied to the lateral edges and the bottom of the geometric model, assuming no heat dissipation through these boundaries.

3.6. Material Removal Modeling

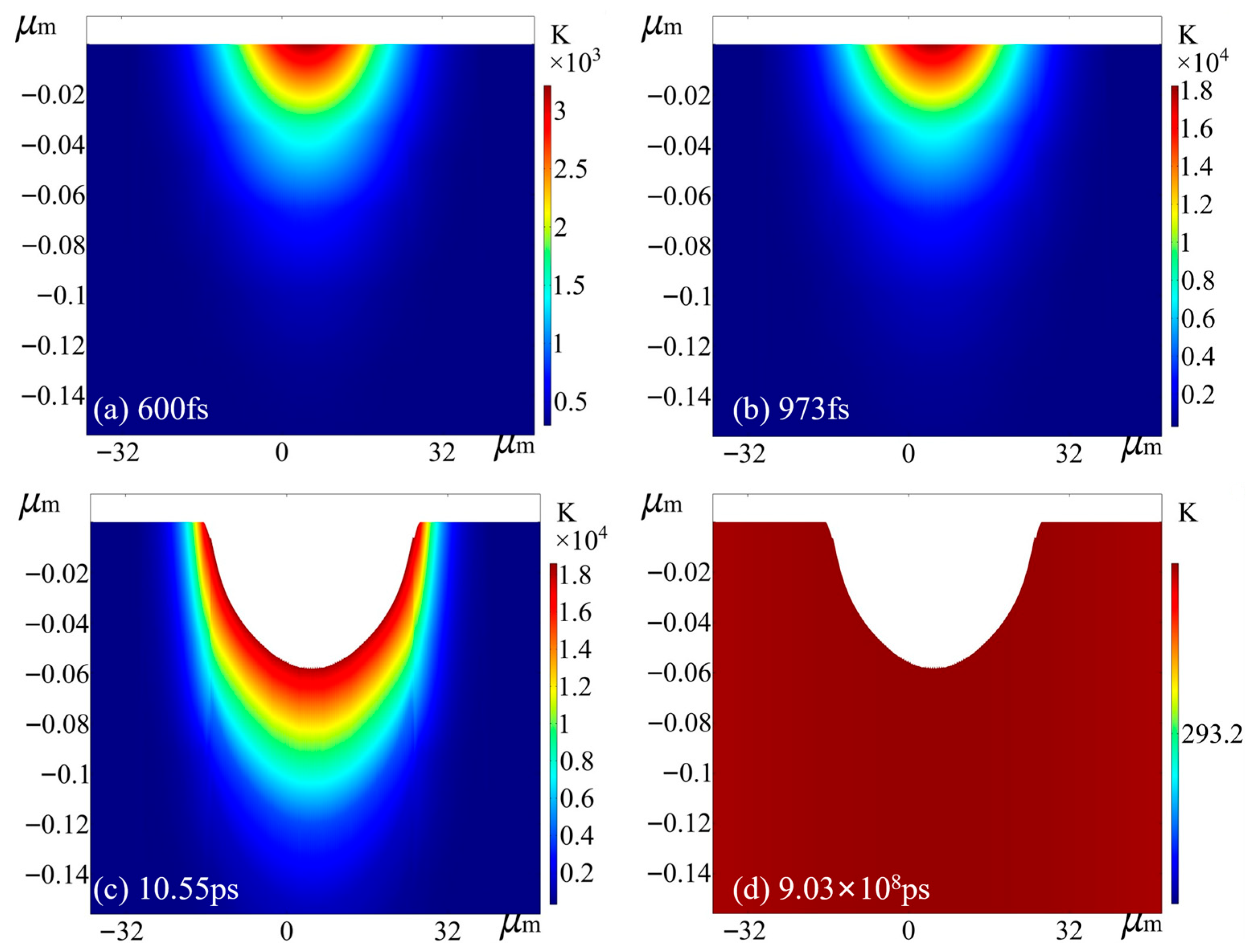

3.7. Model Simulation Results

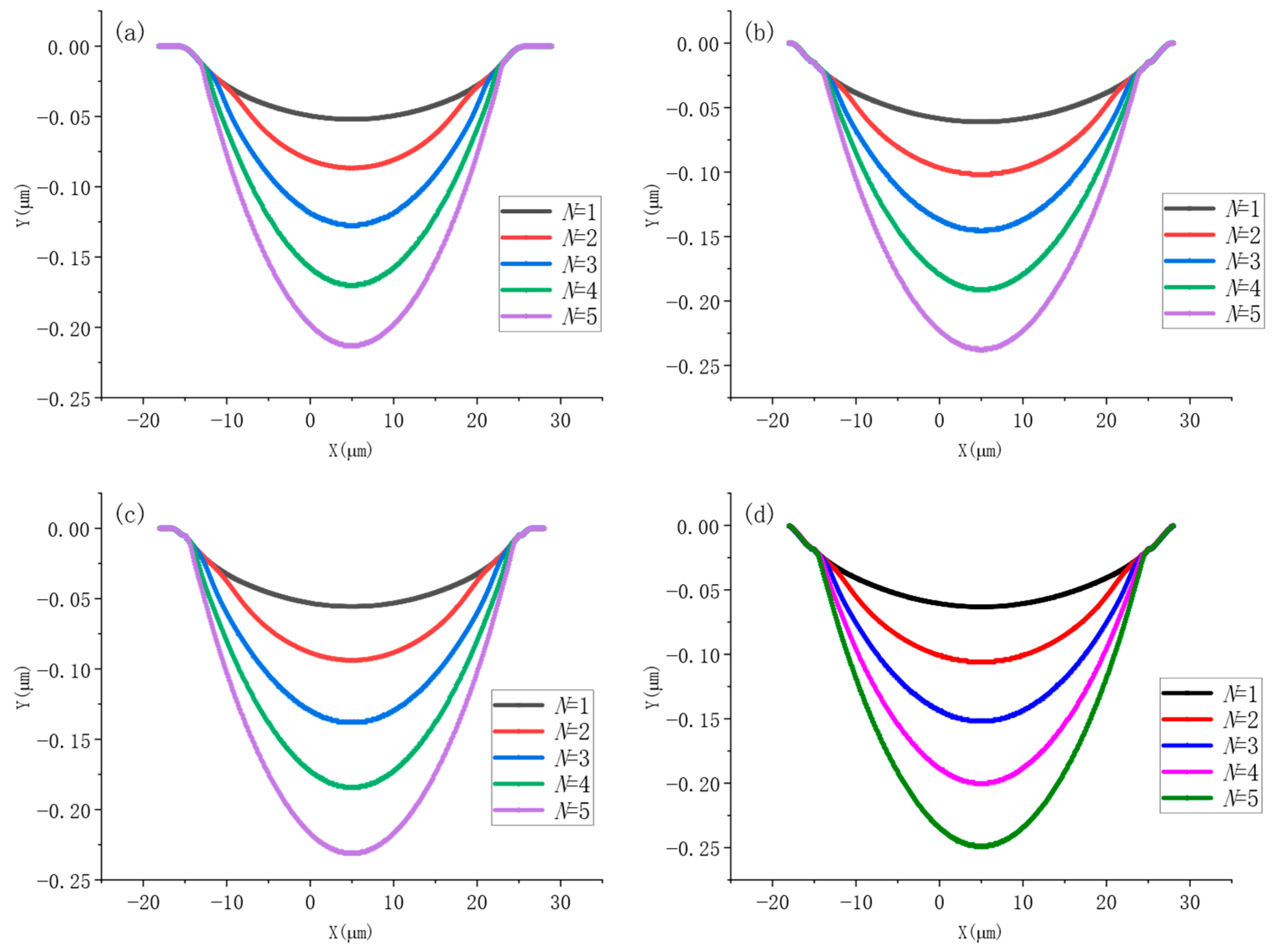

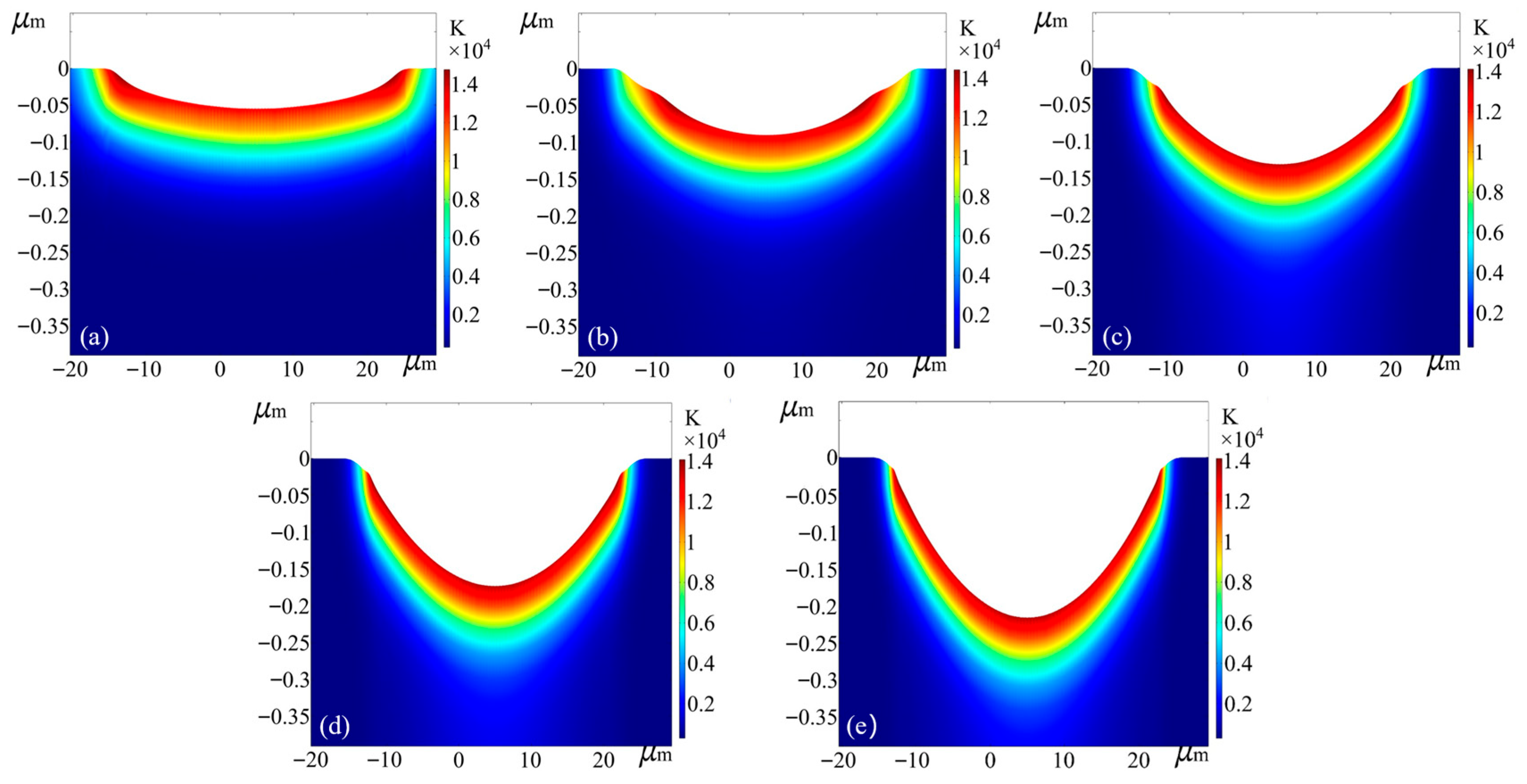

4. Simulation Results Analysis and Discussion

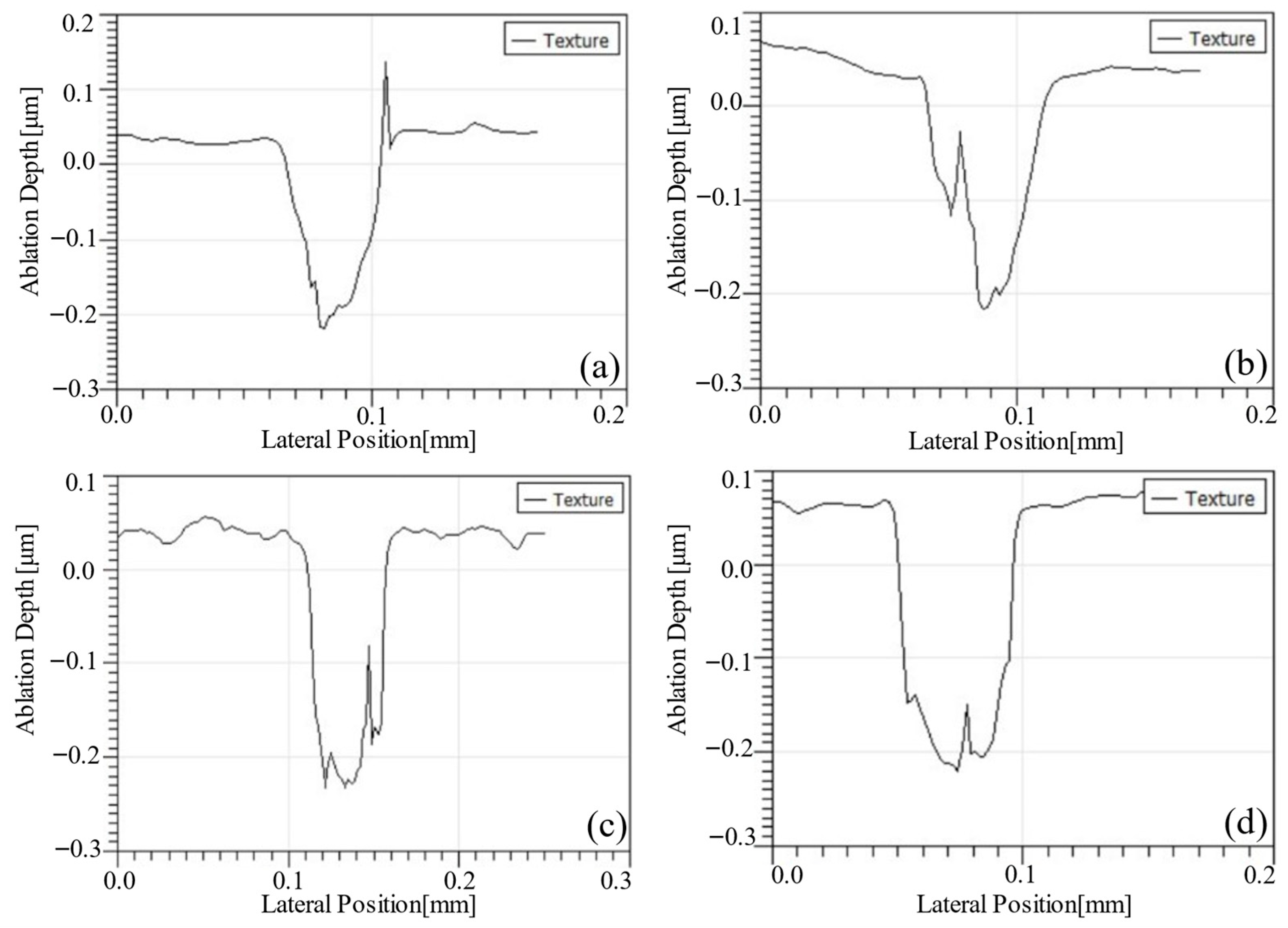

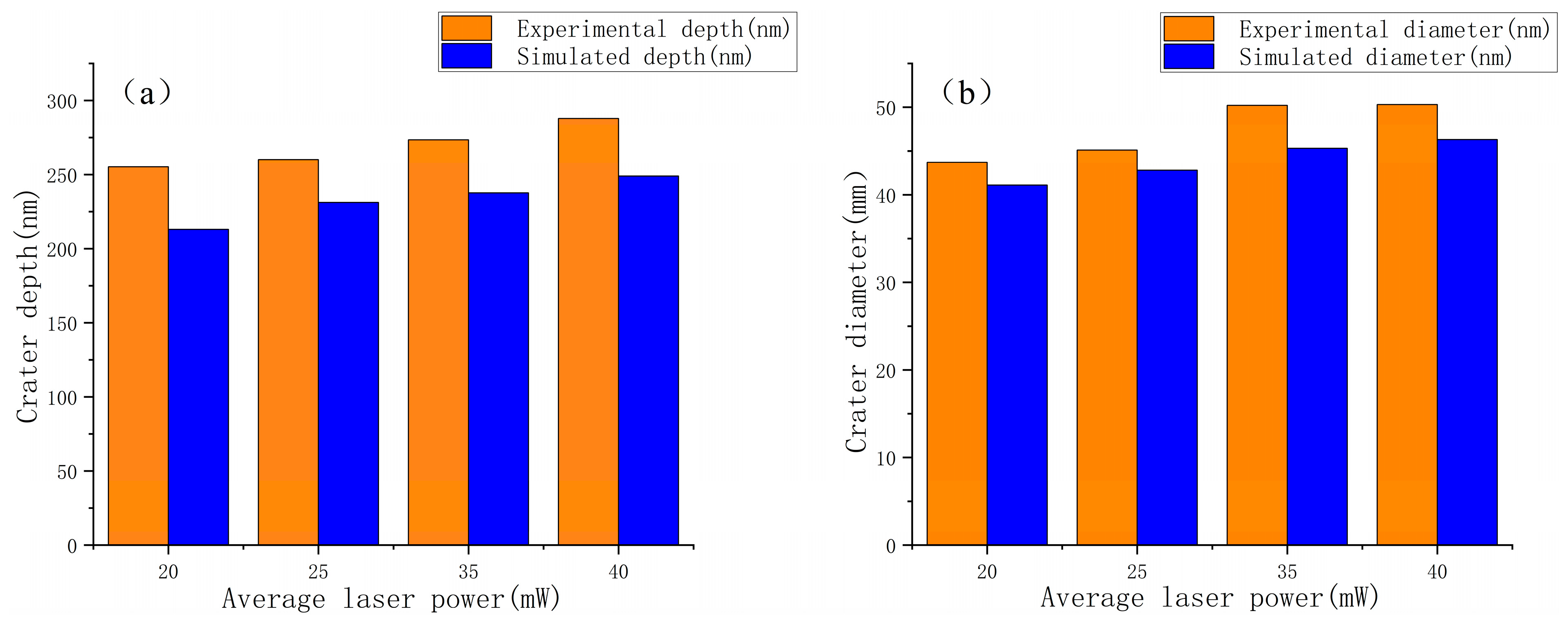

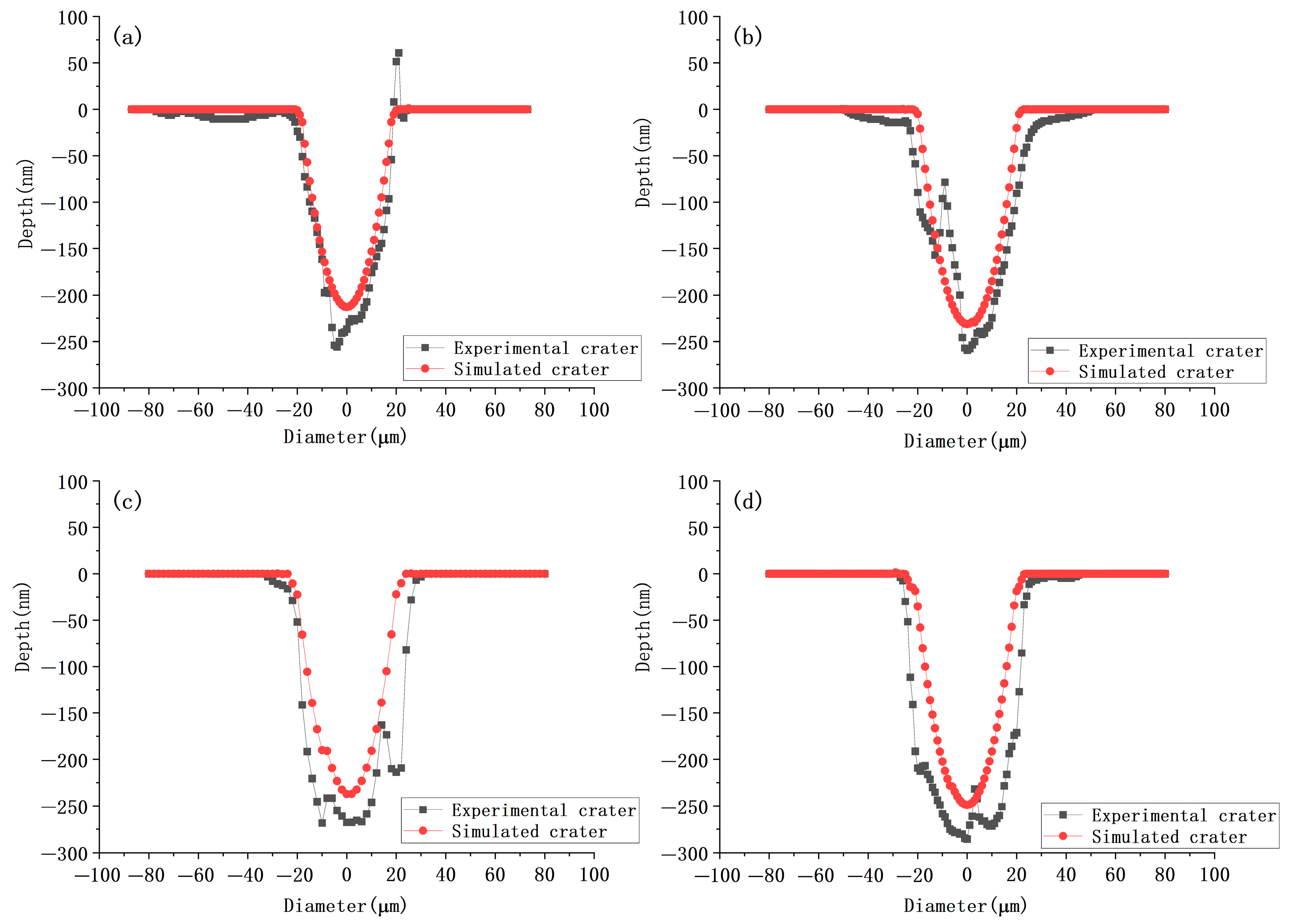

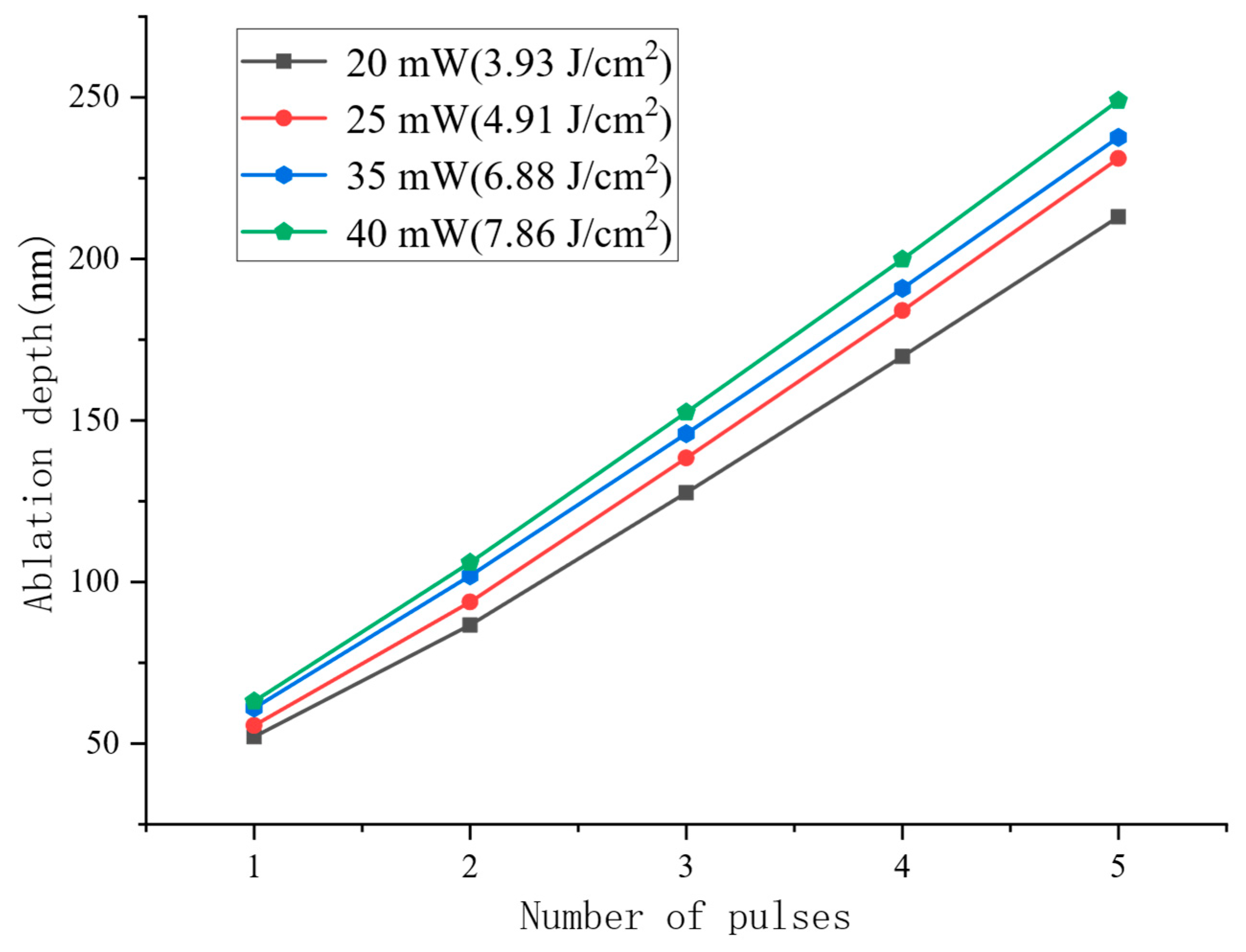

4.1. Experimental Validation of the Simulation Model

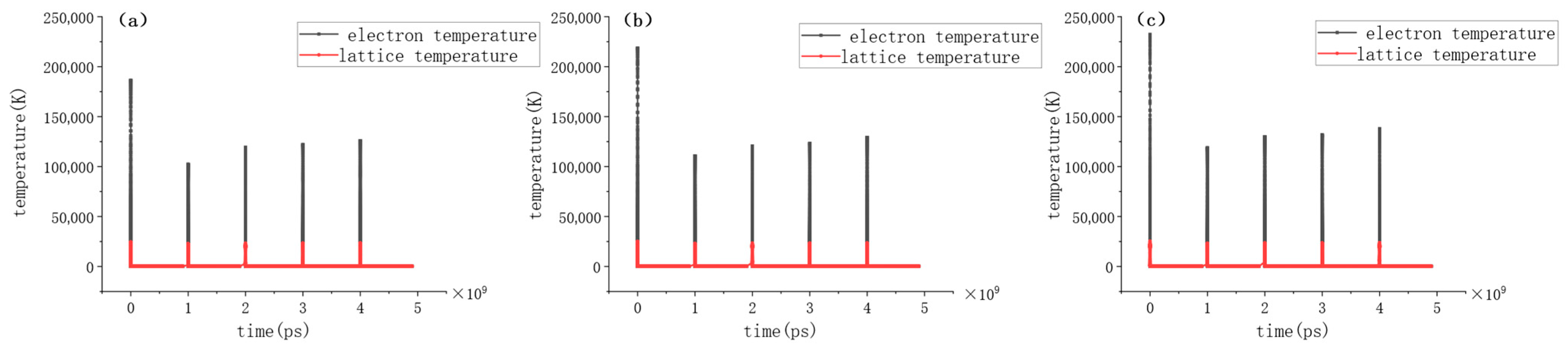

4.2. Changing Law of Electron–Lattice Temperature in Multi-Pulse Ablation Process

4.3. Analysis of Multi-Pulse Ablation Results

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- To investigate the ablation effect of multi-pulse femtosecond lasers on cemented carbide materials, a simulation model was developed based on the two-temperature equation, incorporating the cumulative effect and an improved energy attenuation term in the laser heat source. The simulation results were validated through corresponding multi-pulse laser ablation experiments, showing good agreement with the experimental data. The average errors in crater diameter and depth between simulation and experiment were 7.2% and 13.6%, respectively, and the overall morphologies were also well matched, confirming the accuracy of the simulation model.

- (2)

- The effects of average laser power and pulse number on the ablation process were thoroughly investigated. The second pulse exhibited a reduced peak electron temperature due to the presence of the WC layer, while subsequent pulses showed increasing electron temperatures with higher pulse counts. Additionally, under a fixed pulse number, higher average power led to higher peak electron temperatures.

- (3)

- Temperature field analysis demonstrated that, at a repetition rate of 1 kHz, thermal accumulation between successive pulses was negligible. As the number of pulses increased, both ablation depth and diameter increased, though the diameter grew at a slower rate. Moreover, the ablation depth per pulse increased with pulse number due to the cumulative effect, indicating enhanced material removal efficiency under multi-pulse conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yilbas, B.S.; Arif, A.F.; Karatas, C.; Ahsan, M.J. Cemented carbide cutting tool: Laser processing and thermal stress analysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 253, 5544–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, C.; Yilbas, B.S.; Aleem, A.; Ahsan, M. Laser treatment of cemented carbide cutting tool. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2007, 183, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Li, L.; He, N.; Zhao, G.; Wu, X. Temperature Distribution of Cemented Carbides Irradiated by Pulsed Fiber Laser. China Mech. Eng. 2017, 28, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Chu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y. Nanosecond UV laser induced subsurface damage mechanics of cemented tungsten carbide. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 32927–32937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, G.; Orazi, L.; Fortunato, A.; Cuccolini, G. Laser Ablation of Metals: A 3D Process Simulation for Industrial Applications. J. Eng. Ind. 2008, 130, 31111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, S.I.; Kapeliovich, B.L.; Perelman, T.L. Electron emission from metal surfaces exposed to ultra-short laser pulses. Zhurnal Eksperimental’noi I Teroreticheskoi Fiz. 1974, 66, 776–781. [Google Scholar]

- Detlef, B.; Andreas, R.; Friedrich, D. Fundamental aspects in machining of metals with short and ultrashort laser pulses. Univ. Stuttgart 2004, 5339, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensink, K.; Penilla, E.H.; Martínez-Torres, P.; Cuando-Espitia, N.; Mathaudhu, S.; Aguilar, G. High repetition rate femtosecond laser heat accumulation and ablation thresholds in cobalt-binder and binderless tungsten carbides. J. Mater. Process. Tech 2018, 266, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Li, M.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S. Numerical simulation and investigation of ultra-short pulse laser ablation on Ti6Al4V and stainless steel. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 65018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Huang, J.; Baheti, K.; Zhang, Y. An Axisymmetric Model for Solid-Liquid-Vapor Phase Change in Thin Metal Films Induced by An Ultrashort Laser Pulse. Front. Heat Mass Transf. 2011, 2, 13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lao, H.; Lin, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X. Study of femtosecond ablation on aluminum film with 3D two-temperature model and experimental verifications. Appl. Phys. A 2011, 105, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. Investigation of Mechanisms of Ultrashort Laser Pulse Ablation Through Experiments and Simulations. Ph.D. Thesis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study of Femtosecond Laser Polishing of Titanium Alloy and Stainless Steel. Master’s Thesis, Liaoning University of Science and Technology, Anshan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina, C.J.; Daniel, C.; Emmelmann, C. Experimental and Analytical Investigation of Cemented Tungsten Carbide Ultra-Short Pulse Laser Ablation. Phys. Procedia 2013, 41, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Chen, G.; Zhou, C. Research and application of surface heat treatment for multipulse laser ablation of materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 355, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Xiong, B.; Chen, G.Y.; Wu, J.P. Laser truing and sharpening of bronze-bond diamond grinding wheel. Infrared Laser Eng. 2017, 46, 406008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.J.; Ming, R.; Li, X.K.; Lai, M.; Ma, Y.; Ming, X. Study on morphology characteristics of femtosecond laser-ablated face gear materials. Chin. J. Lasers 2021, 48, 1402017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.Z.; Li, X.K.; Mi, C.J.; He, G.Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, C.; Ming, R. Complex-coupling modeling and morphological effects of femtosecond laser ablation of tooth surfaces. J. Photonics 2023, 52, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Metzner, D.; Lickschat, P.; Weißmantel, S. Laser micromachining of silicon and cemented tungsten carbide using picosecond laser pulses in burst mode. Ablation mechanisms and heat accumulation. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiuso, C.; Giannuzzi, G.; Volpe, A.; Lugarà, P.M.; Choquet, I.; Ancona, A. Incubation during laser ablation with bursts of femtosecond pulses with picosecond delays. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 3801–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J. Simulation and Experimental Research on Nanopicosecond Double-Pulse Laser Processing of CFRP. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mannion, P.; Magee, J.; Coyne, E.; O’cOnnor, G.; Glynn, T. The effect of damage accumulation behaviour on ablation thresholds and damage morphology in ultrafast laser micro- machining of common metals in air. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2004, 233, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tzou, D.; Beraun, J. A semiclassical two-temperature model for ultrafast laser heating. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2005, 49, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J.; Beraun, E.J.; Tham, L.C. Investigation of thermal response caused by pulse laser heating. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A Appl. 2003, 44, 705–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhigilei, V.L.; Celli, V. Electron-phonon coupling and electron heat capacity of metals under conditions of strong electron-phonon nonequilibrium. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 075133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Beraun, J.E. Numerical study of ultrashort laser pulse interactions with metal films. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A Appl. 2001, 40, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Webb, T.; Bitler, W.J. Study of thermal expansion and thermal conductivity of cemented WC-Co composite. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2015, 49, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickschat, P.; Metzner, D.; Weißmantel, S. Fundamental investigations of ultrashort pulsed laser ablation on stainless steel and cemented tungsten carbide. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 109, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Xu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Sui, L.; Ding, D.; Liu, H.; Jin, M. Modeling of femtosecond laser damage threshold on the two-layer metal films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 257, 1678–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamis, G.; Mishchick, K.; Audouard, E.; Hönninger, C.; Mottay, E.; Lopez, J.; Manek-Hönninger, I. High efficiency femtosecond laser ablation with gigahertz levelbursts. J. Laser Appl. 2019, 31, 022205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yan, L.; Li, X.; Xu, H. Fabrication of transition metal dichalcogenides quantum dots based on femtosecond laser ablation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blairs, S.; Abbasi, H.M. Correlation between surface tension and critical temperatures of liquid metals. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 304, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. Mechanism Study of Controllable Bottom Shape Formation by Nanosecond Laser Surface Weaving. Ph.D. Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.K.; Beraun, J.E. Investigation of ultrafast laser ablation using a semiclassical two-temperature model. J. Dir. Energy 2005, 1, 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Nedialkov, N.N.; Imamova, S.E.; Atanasov, P.A. Ablation of metals by ultrashort laser pulses. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2004, 37, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, C.-S.; Shang, S.; Liu, D.; Perrie, W.; Dearden, G.; Watkins, K. A review of ultrafast laser materials micromachining. Opt. Laser Technol. 2013, 46, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Shin, C.Y. A simple model for high fluence ultra-short pulsed laser metal ablation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 253, 4079–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average Input Power | Pulse Energy | Diameters (N = 10) | Diameters (N = 20) | Diameters (N = 30) | Diameters (N = 40) | Diameters (N = 50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 mW | 120 μJ | 41.417 µm | 42.960 µm | 43.977 µm | 45.125 µm | 46.171 µm |

| 200 mW | 200 μJ | 45.270 µm | 46.773 µm | 47.648 µm | 48.710 µm | 49.536 µm |

| 250 mW | 250 μJ | 46.926 µm | 48.364 µm | 49.113 µm | 50.068 µm | 51.048 µm |

| 350 mW | 350 μJ | 49.148 µm | 50.504 µm | 51.325 µm | 52.288 µm | 53.194 µm |

| 400 mW | 400 μJ | 50.027 µm | 51.345 µm | 52.103 µm | 53.158 µm | 53.913 µm |

| Thermophysical Parameter | Notation | Unit | Value | Bibliography |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron density (pure tungsten) | Ne | m−3 | 2.15 (1029) | [25] |

| Fermi temperature (pure tungsten) | TF | K | 1.066 (10) | [9] |

| Specific heat coefficient of electrons | Ce0 | J/m3/K2 | 137.3 | [25] |

| Electronic thermal conductivity coefficient | ke0 | W/m/K | 108.6 | [27] |

| lattice heat capacity | Cl | J/kg/K | 200 | [28] |

| lattice thermal conductivity | kl | W/m/K | 1.086 | [29] |

| Critical temperature (pure tungsten) | Tc | K | 20447 | [32] |

| Electron–lattice coupling coefficient | Gel | W/cm3/K | 1 (1012) | [25] |

| reflectivity | R | 1 | 0.46–0.88 | [28,33] |

| enthalpy of evaporation | Hv | J/kg | 3.69 (106) | [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, S.; Fu, L. Modeling and Simulation of Multi-Pulse Femtosecond Laser Ablation of WC-6Co Cemented Carbide. Micromachines 2026, 17, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010011

Wang J, Xu H, Zhang S, Fu L. Modeling and Simulation of Multi-Pulse Femtosecond Laser Ablation of WC-6Co Cemented Carbide. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jin, Haijiao Xu, Shiwei Zhang, and Lianyu Fu. 2026. "Modeling and Simulation of Multi-Pulse Femtosecond Laser Ablation of WC-6Co Cemented Carbide" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010011

APA StyleWang, J., Xu, H., Zhang, S., & Fu, L. (2026). Modeling and Simulation of Multi-Pulse Femtosecond Laser Ablation of WC-6Co Cemented Carbide. Micromachines, 17(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010011